Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

OLD ABE’S CONVERSION

The Negro population of the little Southern town of Danvers was in a state of excitement such as it seldom reached except at revivals, baptisms, or on Emancipation Day. The cause of the commotion was the anticipated return of the Rev. Abram Dixon’s only son, Robert, who, having taken up his father’s life-work and graduated at one of the schools, had been called to a city church.

When Robert’s ambition to take a college course first became the subject of the village gossip, some said that it was an attempt to force Providence. If Robert were called to preach, they said, he would be endowed with the power from on high, and no intervention of the schools was necessary. Abram Dixon himself had at first rather leaned to this side of the case. He had expressed his firm belief in the theory that if you opened your mouth, the Lord would fill it. As for him, he had no thought of what he should say to his people when he rose to speak. He trusted to the inspiration of the moment, and dashed blindly into speech, coherent or otherwise.

When Robert’s ambition to take a college course first became the subject of the village gossip, some said that it was an attempt to force Providence. If Robert were called to preach, they said, he would be endowed with the power from on high, and no intervention of the schools was necessary. Abram Dixon himself had at first rather leaned to this side of the case. He had expressed his firm belief in the theory that if you opened your mouth, the Lord would fill it. As for him, he had no thought of what he should say to his people when he rose to speak. He trusted to the inspiration of the moment, and dashed blindly into speech, coherent or otherwise.

Himself a plantation exhorter of the ancient type, he had known no school except the fields where he had ploughed and sowed, the woods and the overhanging sky. He had sat under no teacher except the birds and the trees and the winds of heaven. If he did not fail utterly, if his labour was not without fruit, it was because he lived close to nature, and so, near to nature’s God. With him religion was a matter of emotion, and he relied for his results more upon a command of feeling than upon an appeal to reason. So it was not strange that he should look upon his son’s determination to learn to be a preacher as unjustified by the real demands of the ministry.

But as the boy had a will of his own and his father a boundless pride in him, the day came when, despite wagging heads, Robert Dixon went away to be enrolled among the students of a growing college. Since then six years had passed. Robert had spent his school vacations in teaching; and now, for the first time, he was coming home, a full-fledged minister of the gospel.

It was rather a shock to the old man’s sensibilities that his son’s congregation should give him a vacation, and that the young minister should accept; but he consented to regard it as of the new order of things, and was glad that he was to have his boy with him again, although he murmured to himself, as he read his son’s letter through his bone-bowed spectacles: “Vacation, vacation, an’ I wonder ef he reckons de devil’s goin’ to take one at de same time?”

It was a joyous meeting between father and son. The old man held his boy off and looked at him with proud eyes.

“Why, Robbie,” he said, “you—you’s a man!”

“That’s what I’m trying to be, father.” The young man’s voice was deep, and comported well with his fine chest and broad shoulders.

“You’s a bigger man den yo’ father ever was!” said his mother admiringly.

“Oh, well, father never had the advantage of playing football.”

The father turned on him aghast. “Playin’ football!” he exclaimed. “You don’t mean to tell me dat dey ‘lowed men learnin’ to be preachers to play sich games?”

“Oh, yes, they believe in a sound mind in a sound body, and one seems to be as necessary as the other in fighting evil.”

Abram Dixon shook his head solemnly. The world was turning upside down for him.

“Football!” he muttered, as they sat down to supper.

Robert was sorry that he had spoken of the game, because he saw that it grieved his father. He had come intending to avoid rather than to combat his parent’s prejudices. There was no condescension in his thought of them and their ways. They were different; that was all. He had learned new ways. They had retained the old. Even to himself he did not say, “But my way is the better one.”

His father was very full of eager curiosity as to his son’s conduct of his church, and the son was equally glad to talk of his work, for his whole soul was in it.

“We do a good deal in the way of charity work among the churchless and almost homeless city children; and, father, it would do your heart good if you could only see the little ones gathered together learning the first principles of decent living.”

“Mebbe so,” replied the father doubtfully, “but what you doin’ in de way of teachin’ dem to die decent?”

The son hesitated for a moment, and then he answered gently, “We think that one is the companion of the other, and that the best way to prepare them for the future is to keep them clean and good in the present.”

“Do you give ’em good strong doctern, er do you give ’em milk and water?”

“I try to tell them the truth as I see it and believe it. I try to hold up before them the right and the good and the clean and beautiful.”

“Humph!” exclaimed the old man, and a look of suspicion flashed across his dusky face. “I want you to preach fer me Sunday.”

It was as if he had said, “I have no faith in your style of preaching the gospel. I am going to put you to the test.”

Robert faltered. He knew his preaching would not please his father or his people, and he shrank from the ordeal. It seemed like setting them all at defiance and attempting to enforce his ideas over their own. Then a perception of his cowardice struck him, and he threw off the feeling that was possessing him. He looked up to find his father watching him keenly, and he remembered that he had not yet answered.

“I had not thought of preaching here,” he said, “but I will relieve you if you wish it.”

“De folks will want to hyeah you an’ see what you kin do,” pursued his father tactlessly. “You know dey was a lot of ’em dat said I oughn’t ha’ let you go away to school. I hope you’ll silence ’em.”

Robert thought of the opposition his father’s friends had shown to his ambitions, and his face grew hot at the memory. He felt his entire inability to please them now.

“I don’t know, father, that I can silence those who opposed my going away or even please those who didn’t, but I shall try to please One.”

It was now Thursday evening, and he had until Saturday night to prepare his sermon. He knew Danvers, and remembered what a chill fell on its congregations, white or black, when a preacher appeared before them with a manuscript or notes. So, out of concession to their prejudices, he decided not to write his sermon, but to go through it carefully and get it well in hand. His work was often interfered with by the frequent summons to see old friends who stayed long, not talking much, but looking at him with some awe and a good deal of contempt. His trial was a little sorer than he had expected, but he bore it all with the good-natured philosophy which his school life and work in a city had taught him.

The Sunday dawned, a beautiful, Southern summer morning; the lazy hum of the bees and the scent of wild honeysuckle were in the air; the Sabbath was full of the quiet and peace of God; and yet the congregation which filled the little chapel at Danvers came with restless and turbulent hearts, and their faces said plainly: “Rob Dixon, we have not come here to listen to God’s word. We have come here to put you on trial. Do you hear? On trial.”

And the thought, “On trial,” was ringing in the young minister’s mind as he rose to speak to them. His sermon was a very quiet, practical one; a sermon that sought to bring religion before them as a matter of every-day life. It was altogether different from the torrent of speech that usually flowed from that pulpit. The people grew restless under this spiritual reserve. They wanted something to sanction, something to shout for, and here was this man talking to them as simply and quietly as if he were not in church.

As Uncle Isham Jones said, “De man never fetched an amen”; and the people resented his ineffectiveness. Even Robert’s father sat with his head bowed in his hands, broken and ashamed of his son; and when, without a flourish, the preacher sat down, after talking twenty-two minutes by the clock, a shiver of surprise ran over the whole church. His father had never pounded the desk for less than an hour.

Disappointment, even disgust, was written on every face. The singing was spiritless, and as the people filed out of church and gathered in knots about the door, the old-time head-shaking was resumed, and the comments were many and unfavourable.

“Dat’s what his schoolin’ done fo’ him,” said one.

“It wasn’t nothin’ mo’n a lecter,” was another’s criticism.

“Put him ‘side o’ his father,” said one of the Rev. Abram Dixon’s loyal members, “and bless my soul, de ol’ man would preach all roun’ him, and he ain’t been to no college, neither!”

Robert and his father walked home in silence together. When they were in the house, the old man turned to his son and said:

“Is dat de way dey teach you to preach at college?”

“I followed my instructions as nearly as possible, father.”

“Well, Lawd he’p dey preachin’, den! Why, befo’ I’d ha’ been in dat pulpit five minutes, I’d ha’ had dem people moanin’ an’ hollerin’ all over de church.”

“And would they have lived any more cleanly the next day?”

The old man looked at his son sadly, and shook his head as at one of the unenlightened.

Robert did not preach in his father’s church again before his visit came to a close; but before going he said, “I want you to promise me you’ll come up and visit me, father. I want you to see the work I am trying to do. I don’t say that my way is best or that my work is a higher work, but I do want you to see that I am in earnest.”

“I ain’t doubtin’ you mean well, Robbie,” said his father, “but I guess I’d be a good deal out o’ place up thaih.”

“No, you wouldn’t, father. You come up and see me. Promise me.”

And the old man promised.

It was not, however, until nearly a year later that the Rev. Abram Dixon went up to visit his son’s church. Robert met him at the station, and took him to the little parsonage which the young clergyman’s people had provided for him. It was a very simple place, and an aged woman served the young man as cook and caretaker; but Abram Dixon was astonished at what seemed to him both vainglory and extravagance.

“Ain’t you livin’ kin’ o’ high fo’ yo’ raisin’, Robbie?” he asked.

The young man laughed. “If you’d see how some of the people live here, father, you’d hardly say so.”

Abram looked at the chintz-covered sofa and shook his head at its luxury, but Robert, on coming back after a brief absence, found his father sound asleep upon the comfortable lounge.

On the next day they went out together to see something of the city. By the habit of years, Abram Dixon was an early riser, and his son was like him; so they were abroad somewhat before business was astir in the town. They walked through the commercial portion and down along the wharves and levees. On every side the same sight assailed their eyes: black boys of all ages and sizes, the waifs and strays of the city, lay stretched here and there on the wharves or curled on doorsills, stealing what sleep they could before the relentless day should drive them forth to beg a pittance for subsistence.

“Such as these we try to get into our flock and do something for,” said Robert.

His father looked on sympathetically, and yet hardly with full understanding. There was poverty in his own little village, yes, even squalour, but he had never seen anything just like this. At home almost everyone found some open door, and rare was the wanderer who slept out-of-doors except from choice.

At nine o’clock they went to the police court, and the old minister saw many of his race appear as prisoners, receiving brief attention and long sentences. Finally a boy was arraigned for theft. He was a little, wobegone fellow hardly ten years of age. He was charged with stealing cakes from a bakery. The judge was about to deal with him as quickly as with the others, and Abram’s heart bled for the child, when he saw a negro call the judge’s attention. He turned to find that Robert had left his side. There was a whispered consultation, and then the old preacher heard with joy, “As this is his first offence and a trustworthy person comes forward to take charge of him, sentence upon the prisoner will be suspended.”

Robert came back to his father holding the boy by the hand, and together they made their way from the crowded room.

“I’m so glad! I’m so glad!” said the old man brokenly.

“We often have to do this. We try to save them from the first contact with the prison and all that it means. There is no reformatory for black boys here, and they may not go to the institutions for the white; so for the slightest offence they are sent to jail, where they are placed with the most hardened criminals. When released they are branded forever, and their course is usually downward.”

He spoke in a low voice, that what he said might not reach the ears of the little ragamuffin who trudged by his side.

Abram looked down on the child with a sympathetic heart.

“What made you steal dem cakes?” he asked kindly.

“I was hongry,” was the simple reply.

The old man said no more until he had reached the parsonage, and then when he saw how the little fellow ate and how tenderly his son ministered to him, he murmured to himself, “Feed my lambs”; and then turning to his son, he said, “Robbie, dey’s some’p’n in ‘dis, dey’s some’p’n in it, I tell you.”

That night there was a boy’s class in the lower room of Robert Dixon’s little church. Boys of all sorts and conditions were there, and Abram listened as his son told them the old, sweet stories in the simplest possible manner and talked to them in his cheery, practical way. The old preacher looked into the eyes of the street gamins about him, and he began to wonder. Some of them were fierce, unruly-looking youngsters, inclined to meanness and rowdyism, but one and all, they seemed under the spell of their leader’s voice. At last Robert said, “Boys, this is my father. He’s a preacher, too. I want you to come up and shake hands with him.” Then they crowded round the old man readily and heartily, and when they were outside the church, he heard them pause for a moment, and then three rousing cheers rang out with the vociferated explanation, “Fo’ de minister’s pap!”

Abram held his son’s hand long that night, and looked with tear-dimmed eyes at the boy.

“I didn’t understan’,” he said. “I didn’t understan’.”

“You’ll preach for me Sunday, father?”

“I wouldn’t daih, honey. I wouldn’t daih.”

“Oh, yes, you will, pap.”

He had not used the word for a long time, and at sound of it his father yielded.

It was a strange service that Sunday morning. The son introduced the father, and the father, looking at his son, who seemed so short a time ago unlearned in the ways of the world, gave as his text, “A little child shall lead them.”

He spoke of his own conceit and vainglory, the pride of his age and experience, and then he told of the lesson he had learned. “Why, people,” he said, “I feels like a new convert!”

It was a gentler gospel than he had ever preached before, and in the congregation there were many eyes as wet as his own.

“Robbie,” he said, when the service was over, “I believe I had to come up here to be converted.” And Robbie smiled.

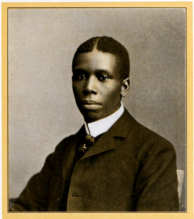

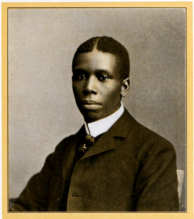

Paul Laurence Dunbar

(1872 – 1906)

Old Abe’s Conversion

From The Heart Of Happy Hollow, a collection of short stories reprinted in 1904 by Dodd, Mead and Company, New York.

Short Story

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive C-D, Archive C-D, Dunbar, Paul Laurence, Dunbar, Paul Laurence, Paul Laurence Dunbar, Paul Laurence Dunbar

Von Liebe

Am Abend sprach das Meer und flüsterte:

Ihr schönen Mägdelein, erzählt mir leise,

Ich will die Liebe wissen! Redet mir

So von der Liebe, gleich als sollte ich

Dran sterben, so als müsst’ in Ruhe ich

Versinken dran, als könnte sie vorm Sturme

Mich schützen, dass so wütend er nicht mehr

Auf mich sich stürzte! – O! so sprachen da

Die Mägdelein, – Wir wissen wahrlich nicht,

Du armes Meer, ob wir erzählen dürfen;

Denn nimmermehr würdst du in wilder Kraft

Die Schiffe schleudern wollen, und der Felsen

Sorgenumwölbte Stirn mit Schaume peitschen,

Noch wälzen unter jähe, grüne Klippen

Der Sterne Blicken. Glaub’ uns Meer, Du wolltest

So mächtig nimmer sein, so scheu und spröde,

In deinen Schoß und in dein Herz nicht mehr

Die schlafumfangnen Menschenherzen saugen.

Du würdest dann gleich uns den Himmel ansehn,

Und ihn nicht sehen, lächeln, wie der Wind

Vorüberweht, und weinen, weil die Sonne

Aufgeht! Nein! wir werden nichts erzählen!

Carmen Sylva

(1843-1916)

Von Liebe

Gedicht

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Archive S-T, CLASSIC POETRY

A Day

I’ll tell you how the sun rose, —

A ribbon at a time.

The steeples swam in amethyst,

The news like squirrels ran.

The hills untied their bonnets,

The bobolinks begun.

Then I said softly to myself,

“That must have been the sun!”

But how he set, I know not.

There seemed a purple stile

Which little yellow boys and girls

Were climbing all the while

Till when they reached the other side,

A dominie in gray

Put gently up the evening bars,

And led the flock away.

Emily Dickinson

(1830-1886)

A Day

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive C-D, Dickinson, Emily

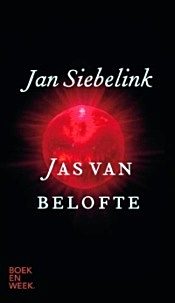

De 84ste editie van de Boekenweek vindt plaats van zaterdag 23 maart tot en met zondag 31 maart en heeft De moeder de vrouw als thema naar het gelijknamige gedicht van Martinus Nijhoff.

Voor de Boekenweek 2019 schreef Jan Siebelink het Boekenweekgeschenk Jas van belofte, dat tijdens de Boekenweek bij besteding van ten minste €12,50 aan Nederlandstalige boeken door de boekhandel cadeau wordt gedaan.

Voor de Boekenweek 2019 schreef Jan Siebelink het Boekenweekgeschenk Jas van belofte, dat tijdens de Boekenweek bij besteding van ten minste €12,50 aan Nederlandstalige boeken door de boekhandel cadeau wordt gedaan.

Het Boekenweekessay is geschreven door Murat Isik en heeft de titel Mijn moeders strijd. Tijdens de Boekenweek is het voor € 3,75 verkrijgbaar in de boekwinkel.

Op 31 maart, de laatste zondag van de Boekenweek, kunnen reizigers traditiegetrouw op het vertoon van het Boekenweekgeschenk gratis met de trein reizen.

Op 31 maart, de laatste zondag van de Boekenweek, kunnen reizigers traditiegetrouw op het vertoon van het Boekenweekgeschenk gratis met de trein reizen.

De moeder de vrouw

Het thema van de Boekenweek 2019 is ontleend aan het beroemde gedicht van Martinus Nijhoff ‘De moeder de vrouw’. Tevens is het Boekenweekthema een verwijzing naar de bundel De moeder de vrouw, met daarin twee romans (Ontaarde moeders en Mijn zoon heeft een seksleven en ik lees mijn moeder Roodkapje voor) over moederschap van de onlangs overleden Renate Dorrestein.

# meer informatie op website boekenweek

Boekweek 2019

van 23 – 31 maart

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book Lovers, - Book News, - Book Stories, - Bookstores, Art & Literature News, Boekenweek, Jan Siebelink, Nijhoff, Martinus

Guerre civile

La foule était tragique et terrible ; on criait :

À mort ! Autour d’un homme altier, point inquiet,

Grave, et qui paraissait lui-même inexorable,

Le peuple se pressait : À mort le misérable !

Et lui, semblait trouver toute simple la mort.

La partie est perdue, on n’est pas le plus fort,

On meurt, soit. Au milieu de la foule accourue,

Les vainqueurs le traînaient de chez lui dans la rue.

— À mort l’homme ! — On l’avait saisi dans son logis ;

Ses vêtements étaient de carnage rougis ;

Cet homme était de ceux qui font l’aveugle guerre

Des rois contre le peuple, et ne distinguent guère

Scévola de Brutus, ni Barbès de Blanqui ;

Il avait tout le jour tué n’importe qui ;

Incapable de craindre, incapable d’absoudre,

Il marchait, laissant voir ses mains noires de poudre ;

Une femme le prit au collet : « À genoux !

C’est un sergent de ville. Il a tiré sur nous !

— C’est vrai, dit l’homme. — À bas ! à mort ! qu’on le fusille !

Dit le peuple. — Ici ! Non ! Plus loin ! À la Bastille !

À l’arsenal ! Allons ! Viens ! Marche ! — Où vous voudrez »,

Dit le prisonnier. Tous, hagards, les rangs serrés,

Chargèrent leurs fusils. « Mort au sergent de ville !

Tuons-le comme un loup ! — Et l’homme dit, tranquille :

— C’est bien, je suis le loup, mais vous êtes les chiens.

— Il nous insulte ! À mort ! » Les pâles citoyens

Croisaient leurs poings crispés sur le captif farouche ;

L’ombre était sur son front et le fiel dans sa bouche ;

Cent voix criaient : « À mort ! À bas ! Plus d’empereur ! »

On voyait dans ses yeux un reste de fureur

Remuer vaguement comme une hydre échouée ;

Il marchait poursuivi par l’énorme huée,

Et, calme, il enjambait, plein d’un superbe ennui,

Des cadavres gisants, peut-être faits par lui.

Le peuple est effrayant lorsqu’il devient tempête ;

L’homme sous plus d’affronts levait plus haut la tête ;

Il était plus que pris, il était envahi.

Dieu ! comme il haïssait ! comme il était haï !

Comme il les eût, vainqueur, fusillés tous ! « Qu’il meure !

Il nous criblait encor de balles tout à l’heure !

À bas cet espion, ce traître, ce maudit !

À mort ! c’est un brigand ! » Soudain on entendit

Une petite voix qui disait : « C’est mon père ! »

Et quelque chose fit l’effet d’une lumière.

Un enfant apparut. Un enfant de six ans.

Ses deux bras se dressaient suppliants, menaçants.

Tous criaient : « Fusillez le mouchard ! Qu’on l’assomme ! »

Et l’enfant se jeta dans les jambes de l’homme,

Et dit, ayant au front le rayon baptismal :

« Père, je ne veux pas qu’on te fasse de mal ! »

Et cet enfant sortait de la même demeure.

Les clameurs grossissaient : « À bas l’homme ! Qu’il meure !

À bas ! finissons-en avec cet assassin !

Mort ! » Au loin le canon répondait au tocsin.

Toute la rue était pleine d’hommes sinistres.

À bas les rois ! À bas les prêtres, les ministres,

Les mouchards ! Tuons tout ! c’est un tas de bandits ! »

Et l’enfant leur cria : « Mais puisque je vous dis

Que c’est mon père ! — Il est joli, dit une femme,

Bel enfant ! » On voyait dans ses yeux bleus une âme ;

Il était tout en pleurs, pâle, point mal vêtu.

Une autre femme dit : « Petit, quel âge as-tu ?

Et l’enfant répondit : — Ne tuez pas mon père ! »

Quelques regards pensifs étaient fixés à terre,

Les poings ne tenaient plus l’homme si durement.

Un de plus furieux, entre tous inclément,

Dit à l’enfant : « Va-t’en ! — Où ? — Chez toi. — Pourquoi faire ?

— Chez ta mère. — Sa mère est morte, dit le père.

— Il n’a donc plus que vous ? — Qu’est-ce que cela fait ? »

Dit le vaincu. Stoïque et calme, il réchauffait

Les deux petites mains dans sa rude poitrine,

Et disait à l’enfant : « Tu sais bien, Catherine ?

— Notre voisine ? — Oui. Va chez elle. — Avec toi ?

— J’irai plus tard. — Sans toi je ne veux pas. — Pourquoi ?

— Parce qu’on te ferait du mal. » Alors le père

Parla tout bas au chef de cette sombre guerre :

« Lâchez-moi le collet. Prenez-moi par la main,

Doucement. Je vais dire à l’enfant : À demain !

Vous me fusillerez au détour de la rue,

Ailleurs, où vous voudrez. — Et, d’une voix bourrue :

— Soit, dit le chef, lâchant le captif à moitié.

Le père dit : — Tu vois. C’est de bonne amitié.

Je me promène avec ces messieurs. Sois bien sage,

Rentre. » Et l’enfant tendit au père son visage,

Et s’en alla content, rassuré, sans effroi.

« Nous sommes à notre aise à présent, tuez-moi,

Dit le père aux vainqueurs ; où voulez-vous que j’aille ? »

Alors, dans cette foule où grondait la bataille,

On entendit passer un immense frisson,

Et le peuple cria : « Rentre dans ta maison ! »

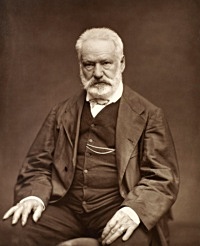

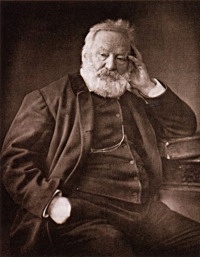

Victor Hugo

(1802-1885)

Guerre civile

(Poème)

La Légende des siècles, 1877

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive G-H, Archive G-H, Hugo, Victor, Victor Hugo

There be none of Beauty’s daughters

Stanzas for Music

There be none of Beauty’s daughters

With a magic like Thee;

And like music on the waters

Is thy sweet voice to me:

When, as if its sound were causing

The charméd ocean’s pausing,

The waves lie still and gleaming,

And the lull’d winds seem dreaming:

And the midnight moon is weaving

Her bright chain o’er the deep,

Whose breast is gently heaving

As an infant’s asleep:

So the spirit bows before thee

To listen and adore thee;

With a full but soft emotion,

Like the swell of Summer’s ocean.

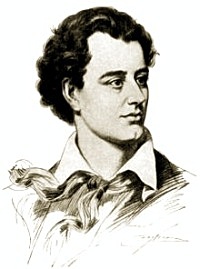

George Gordon Byron

(1788 – 1824)

There be none of Beauty’s daughters

Stanzas for Music

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: # Music Archive, Archive A-B, Archive A-B, Byron, Lord

Les innocents

Mais les enfants sont là. Le murmure qui sort

De ces âmes en fleur est-il compris du sort ?

L’enfant va devant lui gaîment ; mais la prière,

Quand il rit, parle-t-elle à quelqu’un en arrière ?

Le frais chuchotement du doux être enfantin

Attendrit-il l’oreille obscure du destin ?

Oh ! que d’ombre ! Tous deux chantent, fragiles têtes

Où flotte la lueur d’on ne sait quelles fêtes,

Et que dore un reflet d’un paradis lointain !

Les enfants ont des coeurs faits comme le matin

Ils ont une innocence étonnée et joyeuse ;

Et pas plus que l’oiseau gazouillant sous l’yeuse,

Pas plus que l’astre éclos sur les noirs horizons,

Ils ne sont inquiets de ce que nous faisons,

Ayant pour toute affaire et pour toute aventure

L’épanouissement de la grande nature ;

Ils ne demandent rien à Dieu que son soleil ;

Ils sont contents pourvu qu’un beau rayon vermeil

Chauffe les petits doigts de leur main diaphane

Et que le ciel soit bleu, cela suffit à Jeanne.

Victor Hugo

(1802-1885)

Les innocents

(Poème)

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive G-H, Archive G-H, Hugo, Victor, Victor Hugo

THE HOME-COMING OF ‘RASTUS SMITH

There was a great commotion in that part of town which was known as “Little Africa,” and the cause of it was not far to seek. Contrary to the usual thing, this cause was not an excursion down the river, nor a revival, baptising, nor an Emancipation Day celebration. None of these was it that had aroused the denizens of “Little Africa,” and kept them talking across the street from window to window, from door to door, through alley gates, over backyard fences, where they stood loud-mouthed and arms akimboed among laden clothes lines. No, the cause of it all was that Erastus Smith, Aunt Mandy Smith’s boy, who had gone away from home several years before, and who, rumour said, had become a great man, was coming back, and “Little Africa,” from Douglass Street to Cat Alley, was prepared to be dazzled. So few of those who had been born within the mile radius which was “Little Africa” went out into the great world and came into contact with the larger humanity that when one did he became a man set apart. And when, besides, he went into a great city and worked for a lawyer whose name was known the country over, the place of his birth had all the more reason to feel proud of her son.

So there was much talk across the dirty little streets, and Aunt Mandy’s small house found itself all of a sudden a very popular resort. The old women held Erastus up as an example to their sons. The old men told what they might have done had they had his chance. The young men cursed him, and the young girls giggled and waited.

So there was much talk across the dirty little streets, and Aunt Mandy’s small house found itself all of a sudden a very popular resort. The old women held Erastus up as an example to their sons. The old men told what they might have done had they had his chance. The young men cursed him, and the young girls giggled and waited.

It was about an hour before the time of the arrival of Erastus, and the neighbours had thinned out one by one with a delicacy rather surprising in them, in order that the old lady might be alone with her boy for the first few minutes. Only one remained to help put the finishing touches to the two little rooms which Mrs. Smith called home, and to the preparations for the great dinner. The old woman wiped her eyes as she said to her companion, “Hit do seem a speshul blessin’, Lizy, dat I been spaihed to see dat chile once mo’ in de flesh. He sholy was mighty nigh to my hea’t, an’ w’en he went erway, I thought it ‘ud kill me. But I kin see now dat hit uz all fu’ de bes’. Think o’ ‘Rastus comin’ home, er big man! Who’d evah ‘specked dat?”

“Law, Mis’ Smif, you sholy is got reason to be mighty thankful. Des’ look how many young men dere is in dis town what ain’t nevah been no ‘count to dey pa’ents, ner anybody else.”

“Well, it’s onexpected, Lizy, an’ hit’s ‘spected. ‘Rastus allus wuz a wonnerful chil’, an’ de way he tuk to work an’ study kin’ o’ promised something f’om de commencement, an’ I ‘lowed mebbe he tu’n out a preachah.”

“Tush! yo’ kin thank yo’ stahs he didn’t tu’n out no preachah. Preachahs ain’t no bettah den anybody else dese days. Dey des go roun’ tellin’ dey lies an’ eatin’ de whiders an’ orphins out o’ house an’ home.”

“Well, mebbe hit’s bes’ he didn’ tu’n out dat way. But f’om de way he used to stan’ on de chaih an’ ‘zort w’en he was a little boy, I thought hit was des what he ‘ud tu’n out. O’ co’se, being’ in a law office is des as pervidin’, but somehow hit do seem mo’ worl’y.”

“Didn’t I tell you de preachahs is ez worldly ez anybody else?”

“Yes, yes, dat’s right, but den ‘Rastus, he had de eddication, fo’ he had gone thoo de Third Readah.”

Just then the gate creaked, and a little brown-faced girl, with large, mild eyes, pushed open the door and came shyly in.

“Hyeah’s some flowahs, Mis’ Smif,” she said. “I thought mebbe you might like to decorate ‘Rastus’s room,” and she wiped the confusion from her face with her apron.

“La, chil’, thankee. Dese is mighty pu’tty posies.” These were the laurels which Sally Martin had brought to lay at the feet of her home-coming hero. No one in Cat Alley but that queer, quiet little girl would have thought of decorating anybody’s room with flowers, but she had peculiar notions.

In the old days, when they were children, and before Erastus had gone away to become great, they had gone up and down together along the byways of their locality, and had loved as children love. Later, when Erastus began keeping company, it was upon Sally that he bestowed his affections. No one, not even her mother, knew how she had waited for him all these years that he had been gone, few in reality, but so long and so many to her.

And now he was coming home. She scorched something in the ironing that day because tears of joy were blinding her eyes. Her thoughts were busy with the meeting that was to be. She had a brand new dress for the occasion—a lawn, with dark blue dots, and a blue sash—and there was a new hat, wonderful with the flowers of summer, and for both of them she had spent her hard-earned savings, because she wished to be radiant in the eyes of the man who loved her.

Of course, Erastus had not written her; but he must have been busy, and writing was hard work. She knew that herself, and realised it all the more as she penned the loving little scrawls which at first she used to send him. Now they would not have to do any writing any more; they could say what they wanted to each other. He was coming home at last, and she had waited long.

They paint angels with shining faces and halos, but for real radiance one should have looked into the dark eyes of Sally as she sped home after her contribution to her lover’s reception.

When the last one of the neighbours had gone Aunt Mandy sat down to rest herself and to await the great event. She had not sat there long before the gate creaked. She arose and hastened to the window. A young man was coming down the path. Was that ‘Rastus? Could that be her ‘Rastus, that gorgeous creature with the shiny shoes and the nobby suit and the carelessly-swung cane? But he was knocking at her door, and she opened it and took him into her arms.

“Why, howdy, honey, howdy; hit do beat all to see you agin, a great big, grown-up man. You’re lookin’ des’ lak one o’ de big folks up in town.”

Erastus submitted to her endearments with a somewhat condescending grace, as who should say, “Well, poor old fool, let her go on this time; she doesn’t know any better.” He smiled superiorly when the old woman wept glad tears, as mothers have a way of doing over returned sons, however great fools these sons may be. She set him down to the dinner which she had prepared for him, and with loving patience drew from his pompous and reluctant lips some of the story of his doings and some little word about the places he had seen.

“Oh, yes,” he said, crossing his legs, “as soon as Mr. Carrington saw that I was pretty bright, he took me right up and gave me a good job, and I have been working for him right straight along for seven years now. Of course, it don’t do to let white folks know all you’re thinking; but I have kept my ears and my eyes right open, and I guess I know just about as much about law as he does himself. When I save up a little more I’m going to put on the finishing touches and hang out my shingle.”

“Don’t you nevah think no mo’ ’bout bein’ a preachah, ‘Rastus?” his mother asked.

“Haw, haw! Preachah? Well, I guess not; no preaching in mine; there’s nothing in it. In law you always have a chance to get into politics and be the president of your ward club or something like that, and from that on it’s an easy matter to go on up. You can trust me to know the wires.” And so the tenor of his boastful talk ran on, his mother a little bit awed and not altogether satisfied with the new ‘Rastus that had returned to her.

He did not stay in long that evening, although his mother told him some of the neighbours were going to drop in. He said he wanted to go about and see something of the town. He paused just long enough to glance at the flowers in his room, and to his mother’s remark, “Sally Ma’tin brung dem in,” he returned answer, “Who on earth is Sally Martin?”

“Why, ‘Rastus,” exclaimed his mother, “does yo’ ‘tend lak yo’ don’t ‘member little Sally Ma’tin yo’ used to go wid almos’ f’om de time you was babies? W’y, I’m s’prised at you.”

“She has slipped my mind,” said the young man.

For a long while the neighbours who had come and Aunt Mandy sat up to wait for Erastus, but he did not come in until the last one was gone. In fact, he did not get in until nearly four o’clock in the morning, looking a little weak, but at least in the best of spirits, and he vouchsafed to his waiting mother the remark that “the little old town wasn’t so bad, after all.”

Aunt Mandy preferred the request that she had had in mind for some time, that he would go to church the next day, and he consented, because his trunk had come.

It was a glorious Sunday morning, and the old lady was very proud in her stiff gingham dress as she saw her son come into the room arrayed in his long coat, shiny hat, and shinier shoes. Well, if it was true that he was changed, he was still her ‘Rastus, and a great comfort to her. There was no vanity about the old woman, but she paused before the glass a longer time than usual, settling her bonnet strings, for she must look right, she told herself, to walk to church with that elegant son of hers. When he was all ready, with cane in hand, and she was pausing with the key in the door, he said, “Just walk on, mother, I’ll catch you in a minute or two.” She went on and left him.

He did not catch her that morning on her way to church, and it was a sore disappointment, but it was somewhat compensated for when she saw him stalking into the chapel in all his glory, and every head in the house turned to behold him.

There was one other woman in “Little Africa” that morning who stopped for a longer time than usual before her looking-glass and who had never found her bonnet strings quite so refractory before. In spite of the vexation of flowers that wouldn’t settle and ribbons that wouldn’t tie, a very glad face looked back at Sally Martin from her little mirror. She was going to see ‘Rastus, ‘Rastus of the old days in which they used to walk hand in hand. He had told her when he went away that some day he would come back and marry her. Her heart fluttered hotly under her dotted lawn, and it took another application of the chamois to take the perspiration from her face. People had laughed at her, but that morning she would be vindicated. He would walk home with her before the whole church. Already she saw him bowing before her, hat in hand, and heard the set phrase, “May I have the pleasure of your company home?” and she saw herself sailing away upon his arm.

She was very happy as she sat in church that morning, as happy as Mrs. Smith herself, and as proud when she saw the object of her affections swinging up the aisle to the collection table, and from the ring she knew that it could not be less than a half dollar that he put in.

There was a special note of praise in her voice as she joined in singing the doxology that morning, and her heart kept quivering and fluttering like a frightened bird as the people gathered in groups, chattering and shaking hands, and he drew nearer to her. Now they were almost together; in a moment their eyes would meet. Her breath came quickly; he had looked at her, surely he must have seen her. His mother was just behind him, and he did not speak. Maybe she had changed, maybe he had forgotten her. An unaccustomed boldness took possession of her, and she determined that she would not be overlooked. She pressed forward. She saw his mother take his arm and heard her whisper, “Dere’s Sally Ma’tin” this time, and she knew that he looked at her. He bowed as if to a stranger, and was past her the next minute. When she saw him again he was swinging out of the door between two admiring lines of church-goers who separated on the pavement. There was a brazen yellow girl on his arm.

She felt weak and sick as she hid behind the crowd as well as she could, and for that morning she thanked God that she was small.

Aunt Mandy trudged home alone, and when the street was cleared and the sexton was about to lock up, the girl slipped out of the church and down to her own little house. In the friendly shelter of her room she took off her gay attire and laid it away, and then sat down at the window and looked dully out. For her, the light of day had gone out.

Paul Laurence Dunbar

(1872 – 1906)

The Home-Coming Of ‘Rastus Smith

From The Heart Of Happy Hollow, a collection of short stories reprinted in 1904 by Dodd, Mead and Company, New York. Short Story

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive C-D, Archive C-D, Dunbar, Paul Laurence, Dunbar, Paul Laurence, Paul Laurence Dunbar, Paul Laurence Dunbar

An die Freiheit

Goldne Freiheit, kehre wieder

In mein wundes Herz zurück,

Weck’ mir neue, heit’re Lieder

Und entwölke Geist und Blick.

Komm und trockne meine Thränen

Mit der rosig-zarten Hand,

Stille meines Busens Sehnen,

Löse, was die Liebe band.

Liebe schafft Olympos-Freuden,

Und wer ehrte sie wie ich? –

Tiefer doch sind ihre Leiden,

Und allein sie trafen mich.

Ach! mit Jahren voller Qualen,

Mit des halben Lebens Glück

Mußt’ ich ihre Wonne zahlen,

Flüchtig, wie ein Augenblick.

Ohne Freuden stieg der Morgen

Für mich arme Schwärmerin,

Und der Liebe bleiche Sorgen

Welkten meinen Frühling hin.

Wonne hat sie mir versprochen,

Treue war mein Gegenschwur,

Unsern Bund hat sie gebrochen,

Schmerz und Tränen gab sie nur. –

Nimm für deine Palmenkrone

Was die Liebe mir verspricht,

Hier in dieser Männer-Zone

Grünt für mich die Myrte nicht.

Goldne Freiheit, kehre wieder,

Stimme meiner Harfe Ton;

Jubelt lauter, meine Lieder,

Ihr Umarmen fühl’ ich schon!

Sophie Albrecht

(1757-1840)

Gedicht

An die Freiheit

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Archive A-B, CLASSIC POETRY, Galerie Deutschland

Les fusillés

… Partout la mort. Eh bien, pas une plainte.

Ô blé que le destin fauche avant qu’il soit mûr !

Ô peuple !

On les amène au pied de l’affreux mur.

C’est bien. Ils ont été battus du vent contraire.

L’homme dit au soldat qui l’ajuste : Adieu, frère.

La femme dit : – Mon homme est tué. C’est assez.

Je ne sais s’il eut tort ou raison, mais je sais

Que nous avons traîné le malheur côte à côte ;

Il fut mon compagnon de chaîne ; si l’on m’ôte

Cet homme, je n’ai plus besoin de vivre. Ainsi

Puisqu’il est mort, il faut que je meure. Merci. –

Et dans les carrefours les cadavres s’entassent.

Dans un noir peloton vingt jeunes filles passent ;

Elles chantent ; leur grâce et leur calme innocent

Inquiètent la foule effarée ; un passant

Tremble. – Où donc allez-vous ? dit-il à la plus belle.

Parlez. – Je crois qu’on va nous fusiller, dit-elle.

Un bruit lugubre emplit la caserne Lobau ;

C’est le tonnerre ouvrant et fermant le tombeau.

Là des tas d’hommes sont mitraillés ; nul ne pleure ;

Il semble que leur mort à peine les effleure,

Qu’ils ont hâte de fuir un monde âpre, incomplet,

Triste, et que cette mise en liberté leur plaît.

Nul ne bronche. On adosse à la même muraille

Le petit-fils avec l’aïeul, et l’aïeul raille,

Et l’enfant blond et frais s’écrie en riant : Feu ! […]

Victor Hugo

(1802-1885)

Les fusillés

(Poème)

L’année terrible

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive G-H, Archive G-H, Hugo, Victor, Victor Hugo

John Keats Poem

Who killed John Keats?

‘I,’ says the Quarterly,

So savage and Tartarly;

”Twas one of my feats.’

Who shot the arrow?

‘The poet-priest Milman

(So ready to kill man),

Or Southey or Barrow.

George Gordon Byron

(1788 – 1824)

John Keats Poem

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Archive A-B, Byron, Lord, Keats, John

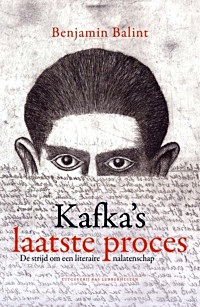

Het nagelaten werk van Franz Kafka is dankzij zijn vriend Max Brod bewaard gebleven, maar na het overlijden van Brod in 1968 begint een hevige en absurde strijd om het eigendomsrecht.

De originele, handgeschreven versies van meesterwerken als Het proces en De gedaanteverwisseling komen achtereenvolgens in handen van Brods secretaresse Esther Hoffe en haar dochter Eva.

De originele, handgeschreven versies van meesterwerken als Het proces en De gedaanteverwisseling komen achtereenvolgens in handen van Brods secretaresse Esther Hoffe en haar dochter Eva.

Er ontvouwt zich echter een juridisch getouwtrek als zowel Israël als Duitsland het werk claimen.

Duitsland, waar drie zussen van Kafka stierven tijdens de Tweede Wereldoorlog, wil de schrijver recht doen, en Israël meent rechten te hebben als Joodse staat en Kafka’s gedroomde land.

Kafka’s laatste proces leest als een waargebeurde thriller, maar maakt pijnlijk duidelijk hoe de Joodse schrijver Franz Kafka inzet wordt van zionistische claims. In de verbeten strijd die de twee landen uitvechten, lijken ze vooral de geschiedenis te willen herschrijven.

Benjamin Balint woont in Jeruzalem, waar hij verbonden is aan het Van Leer Institute. Hij schrijft o.a. voor Haaretz en de Wall Street Journal. Over de Joods-Amerikaanse schrijvers die publiceerden in het tijdschrift Commentary, schreef hij Running Commentary (2010).

Benjamin Balint (Auteur)

Kafka’s laatste proces.

De strijd om een literaire nalatenschap

Vertaling Frank Lekens

Oorspronkelijke titel:

Kafka’s Last Trial.

The Case of a Literary Legacy

Omslagtekening Jirí Slíva

Omslag Bart van den Tooren

Uitg. Bas Lubberhuizen

304 pagina’s

15 x 23 cm

Geïllustreerde paperback

ISBN 9789059375284

Verschenen: januari 2019

€ 24,99

# New books

Benjamin Balint

Kafka’s Last Trial.

The Case of a Literary Legacy

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Bookstores, Archive A-B, Archive K-L, Archive K-L, Art & Literature News, Franz Kafka, Kafka, Franz, Kafka, Franz

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature