Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

Water

The water understands

Civilization well;

It wets my foot, but prettily,

It chills my life, but wittily,

It is not disconcerted,

It is not broken-hearted:

Well used, it decketh joy,

Adorneth, doubleth joy:

Ill used, it will destroy,

In perfect time and measure

With a face of golden pleasure

Elegantly destroy.

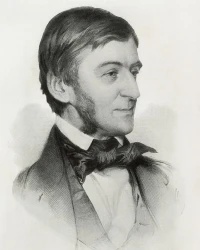

Ralph Waldo Emerson

(1803 – 1882)

Water

•fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: *Archive African American Literature, Archive E-F, Archive E-F, Emerson, Ralph Waldo

The Dying Slave

Faint-gazing on the burning orb of day,

When Afric’s injured son expiring lay,

His forehead cold, his labouring bosom bare,

His dewy temples, and his sable hair,

His poor companions kissed, and cried aloud,

Rejoicing, whilst his head in peace he bowed:—

Now thy long, long task is done,

Swiftly, brother, wilt thou run,

Ere to-morrow’s golden beam

Glitter on thy parent stream,

Swiftly the delights to share,

The feast of joy that waits thee there.

Swiftly, brother, wilt thou ride

O’er the long and stormy tide,

Fleeter than the hurricane,

Till thou see’st those scenes again,

Where thy father’s hut was reared,

Where thy mother’s voice was heard;

Where thy infant brothers played

Beneath the fragrant citron shade;

Where through green savannahs wide

Cooling rivers silent glide,

Or the shrill cicalas sing

Ceaseless to their murmuring;

Where the dance, the festive song,

Of many a friend divided long,

Doomed through stranger lands to roam,

Shall bid thy spirit welcome home!

Fearless o’er the foaming tide

Again thy light canoe shall ride;

Fearless on the embattled plain

Thou shalt lift thy lance again;

Or, starting at the call of morn,

Wake the wild woods with thy horn;

Or, rushing down the mountain-slope,

O’ertake the nimble antelope;

Or lead the dance, ‘mid blissful bands,

On cool Andracte’s yellow sands;

Or, in the embowering orange-grove,

Tell to thy long-forsaken love

The wounds, the agony severe,

Thy patient spirit suffered here!

Fear not now the tyrant’s power,

Past is his insulting hour;

Mark no more the sullen trait

On slavery’s brow of scorn and hate;

Hear no more the long sigh borne

Murmuring on the gales of morn!

Go in peace; yet we remain

Far distant toiling on in pain;

Ere the great Sun fire the skies

To our work of woe we rise;

And see each night, without a friend,

The world’s great comforter descend!

Tell our brethren, where ye meet,

Thus we toil with weary feet;

Yet tell them that Love’s generous flame,

In joy, in wretchedness the same,

In distant worlds was ne’er forgot;

And tell them that we murmur not;

Tell them, though the pang will start,

And drain the life-blood from the heart,—

Tell them, generous shame forbids

The tear to stain our burning lids!

Tell them, in weariness and want,

For our native hills we pant,

Where soon, from shame and sorrow free,

We hope in death to follow thee!

William Lisle Bowles

(1762 – 1850)

The Dying Slave

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: # Classic Poetry Archive, *Archive African American Literature, Archive A-B, Archive A-B, Black Lives Matter, Racism

To Winter

Stay, season of calm love and soulful snows!

There is a subtle sweetness in the sun,

The ripples on the stream’s breast gaily run,

The wind more boisterously by me blows,

And each succeeding day now longer grows.

The birds a gladder music have begun,

The squirrel, full of mischief and of fun,

From maples’ topmost branch the brown twig throws.

I read these pregnant signs, know what they mean:

I know that thou art making ready to go.

Oh stay! I fled a land where fields are green

Always, and palms wave gently to and fro,

And winds are balmy, blue brooks ever sheen,

To ease my heart of its impassioned woe.

Claude McKay

(1889 – 1948)

To Winter

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: #Modern Poetry Archive, 4SEASONS#Winter, Archive M-N, Archive M-N, Claude McKay

THE PROMOTER

Even as early as September, in the year of 1870, the newly emancipated had awakened to the perception of the commercial advantages of freedom, and had begun to lay snares to catch the fleet and elusive dollar.

Those co ntroversialists who say that the Negro’s only idea of freedom was to live without work are either wrong, malicious, or they did not know Little Africa when the boom was on; when every little African, fresh from the fields and cabins, dreamed only of untold wealth and of mansions in which he would have been thoroughly uncomfortable.

ntroversialists who say that the Negro’s only idea of freedom was to live without work are either wrong, malicious, or they did not know Little Africa when the boom was on; when every little African, fresh from the fields and cabins, dreamed only of untold wealth and of mansions in which he would have been thoroughly uncomfortable.

These were the devil’s sunny days, and early and late his mowers were in the field. These were the days of benefit societies that only benefited the shrewdest man; of mutual insurance associations, of wild building companies, and of gilt-edged land schemes wherein the unwary became bogged. This also was the day of Mr. Jason Buford, who, having been free before the war, knew a thing or two, and now had set himself up as a promoter. Truly he had profited by the example of the white men for whom he had so long acted as messenger and factotum.

As he frequently remarked when for purposes of business he wished to air his Biblical knowledge, “I jest takes the Scripter fur my motter an’ foller that ol’ passage where it says, ‘Make hay while the sun shines, fur the night cometh when no man kin work.'”

It is related that one of Mr. Buford’s customers was an old plantation exhorter. At the first suggestion of a Biblical quotation the old gentleman closed his eyes and got ready with his best amen. But as the import of the words dawned on him he opened his eyes in surprise, and the amen died a-borning. “But do hit say dat?” he asked earnestly.

“It certainly does read that way,” said the promoter glibly.

“Uh, huh,” replied the old man, settling himself back in his chair. “I been preachin’ dat t’ing wrong fu’ mo’ dan fo’ty yeahs. Dat’s whut comes o’ not bein’ able to read de wo’d fu’ yo’se’f.”

Buford had no sense of the pathetic or he could never have done what he did—sell to the old gentleman, on the strength of the knowledge he had imparted to him, a house and lot upon terms so easy that he might drowse along for a little time and then wake to find himself both homeless and penniless. This was the promoter’s method, and for so long a time had it proved successful that he had now grown mildly affluent and had set up a buggy in which to drive about and see his numerous purchasers and tenants.

Buford was a suave little yellow fellow, with a manner that suggested the training of some old Southern butler father, or at least, an experience as a likely house-boy. He was polite, plausible, and more than all, resourceful. All of this he had been for years, but in all these years he had never so risen to the height of his own uniqueness as when he conceived and carried into execution the idea of the “Buford Colonizing Company.”

Humanity has always been looking for an Eldorado, and, however mixed the metaphor may be, has been searching for a Moses to lead it thereto. Behold, then, Jason Buford in the rôle of Moses. And equipped he was to carry off his part with the very best advantage, for though he might not bring water from the rock, he could come as near as any other man to getting blood from a turnip.

The beauty of the man’s scheme was that no offering was too small to be accepted. Indeed, all was fish that came to his net.

Think of paying fifty cents down and knowing that some time in the dim future you would be the owner of property in the very heart of a great city where people would rush to buy. It was glowing enough to attract a people more worldly wise than were these late slaves. They simply fell into the scheme with all their souls; and off their half dollars, dollars, and larger sums, Mr. Buford waxed opulent. The land meanwhile did not materialise.

It was just at this time that Sister Jane Callender came upon the scene and made glad the heart of the new-fledged Moses. He had heard of Sister Jane before, and he had greeted her coming with a sparkling of eyes and a rubbing of hands that betokened a joy with a good financial basis.

The truth about the newcomer was that she had just about received her pension, or that due to her deceased husband, and she would therefore be rich, rich to the point where avarice would lie in wait for her.

Sis’ Jane settled in Mr. Buford’s bailiwick, joined the church he attended, and seemed only waiting with her dollars for the very call which he was destined to make. She was hardly settled in a little three-room cottage before he hastened to her side, kindly intent, or its counterfeit, beaming from his features. He found a weak-looking old lady propped in a great chair, while another stout and healthy-looking woman ministered to her wants or stewed about the house in order to be doing something.

“Ah, which—which is Sis’ Jane Callender,” he asked, rubbing his hands for all the world like a clothing dealer over a good customer.

“Dat’s Sis’ Jane in de cheer,” said the animated one, pointing to her charge. “She feelin’ mighty po’ly dis evenin’. What might be yo’ name?” She was promptly told.

“Sis’ Jane, hyeah one de good brothahs come to see you to offah his suvices if you need anything.”

“Thanky, brothah, charity,” said the weak voice, “sit yo’se’f down. You set down, Aunt Dicey. Tain’t no use a runnin’ roun’ waitin’ on me. I ain’t long fu’ dis worl’ nohow, mistah.”

“Buford is my name an’ I came in to see if I could be of any assistance to you, a-fixin’ up yo’ mattahs er seein’ to anything for you.”

“Hit’s mighty kind o’ you to come, dough I don’ ‘low I’ll need much fixin’ fu’ now.”

“Oh, we hope you’ll soon be better, Sistah Callender.”

“Nevah no mo’, suh, ’til I reach the Kingdom.”

“Sis’ Jane Callender, she have been mighty sick,” broke in Aunt Dicey Fairfax, “but I reckon she gwine pull thoo’, the Lawd willin’.”

“Amen,” said Mr. Buford.

“Huh, uh, children, I done hyeahd de washin’ of de waters of Jerdon.”

“No, no, Sistah Callendah, we hope to see you well and happy in de injoyment of de pension dat I understan’ de gov’ment is goin’ to give you.”

“La, chile, I reckon de white folks gwine to git dat money. I ain’t nevah gwine to live to ‘ceive it. Des’ aftah I been wo’kin’ so long fu’ it, too.”

The small eyes of Mr. Buford glittered with anxiety and avarice. What, was this rich plum about to slip from his grasp, just as he was about to pluck it? It should not be. He leaned over the old lady with intense eagerness in his gaze.

“You must live to receive it,” he said, “we need that money for the race. It must not go back to the white folks. Ain’t you got nobody to leave it to?”

“Not a chick ner a chile, ‘ceptin’ Sis’ Dicey Fairfax here.”

Mr. Buford breathed again. “Then leave it to her, by all means,” he said.

“I don’ want to have nothin’ to do with de money of de daid,” said Sis’ Dicey Fairfax.

“Now, don’t talk dat away, Sis’ Dicey,” said the sick woman. “Brother Buford is right, case you sut’ny has been good to me sence I been layin’ hyeah on de bed of affliction, an’ dey ain’t nobody more fitterner to have dat money den you is. Ef de Lawd des lets me live long enough, I’s gwine to mek my will in yo’ favoh.”

“De Lawd’s will be done,” replied the other with resignation, and Mr. Buford echoed with an “Amen!”

He stayed very long that evening, planning and talking with the two old women, who received his words as the Gospel. Two weeks later the Ethiopian Banner, which was the organ of Little Africa, announced that Sis’ Jane Callender had received a back pension which amounted to more than five hundred dollars. Thereafter Mr. Buford was seen frequently in the little cottage, until one day, after a lapse of three or four weeks, a policeman entered Sis’ Jane Callender’s cottage and led her away amidst great excitement to prison. She was charged with pension fraud, and against her protestations, was locked up to await the action of the Grand Jury.

The promoter was very active in his client’s behalf, but in spite of all his efforts she was indicted and came up for trial.

It was a great day for the denizens of Little Africa, and they crowded the court room to look upon this stranger who had come among them to grow so rich, and then suddenly to fall so low.

The prosecuting attorney was a young Southerner, and when he saw the prisoner at the bar he started violently, but checked himself. When the prisoner saw him, however, she made no effort at self control.

“Lawd o’ mussy,” she cried, spreading out her black arms, “if it ain’t Miss Lou’s little Bobby.”

The judge checked the hilarity of the audience; the prosecutor maintained his dignity by main force, and the bailiff succeeded in keeping the old lady in her place, although she admonished him: “Pshaw, chile, you needn’t fool wid me, I nussed dat boy’s mammy when she borned him.”

It was too much for the young attorney, and he would have been less a man if it had not been. He came over and shook her hand warmly, and this time no one laughed.

It was really not worth while prolonging the case, and the prosecution was nervous. The way that old black woman took the court and its officers into her bosom was enough to disconcert any ordinary tribunal. She patronised the judge openly before the hearing began and insisted upon holding a gentle motherly conversation with the foreman of the jury.

She was called to the stand as the very first witness.

“What is your name?” asked the attorney.

“Now, Bobby, what is you axin’ me dat fu’? You know what my name is, and you one of de Fairfax fambly, too. I ‘low ef yo’ mammy was hyeah, she’d mek you ‘membah; she’d put you in yo’ place.”

The judge rapped for order.

“That is just a manner of proceeding,” he said; “you must answer the question, so the rest of the court may know.”

“Oh, yes, suh, ‘scuse me, my name hit’s Dicey Fairfax.”

The attorney for the defence threw up his hands and turned purple. He had a dozen witnesses there to prove that they had known the woman as Jane Callender.

“But did you not give your name as Jane Callender?”

“I object,” thundered the defence.

“Do, hush, man,” Sis’ Dicey exclaimed, and then turning to the prosecutor, “La, honey, you know Jane Callender ain’t my real name, you knows dat yo’se’f. It’s des my bus’ness name. W’y, Sis’ Jane Callender done daid an’ gone to glory too long ‘go fu’ to talk erbout.”

“Then you admit to the court that your name is not Jane Callender?”

“Wha’s de use o’ my ‘mittin’, don’ you know it yo’se’f, suh? Has I got to come hyeah at dis late day an’ p’ove my name an’ redentify befo’ my ol’ Miss’s own chile? Mas’ Bob, I nevah did t’ink you’d ac’ dat away. Freedom sutny has done tuk erway yo’ mannahs.”

“Yes, yes, yes, that’s all right, but we want to establish the fact that your name is Dicey Fairfax.”

“Cose it is.”

“Your Honor, I object—I——”

“Your Honor,” said Fairfax coldly, “will you grant me the liberty of conducting the examination in a way somewhat out of the ordinary lines? I believe that my brother for the defence will have nothing to complain of. I believe that I understand the situation and shall be able to get the truth more easily by employing methods that are not altogether technical.”

The court seemed to understand a thing or two himself, and overruled the defence’s objection.

“Now, Mrs. Fairfax——”

Aunt Dicey snorted. “Hoomph? What? Mis’ Fairfax? What ou say, Bobby Fairfax? What you call me dat fu’? My name Aunt Dicey to you an’ I want you to un’erstan’ dat right hyeah. Ef you keep on foolin’ wid me, I ‘spec’ my patience gwine waih claih out.”

“Excuse me. Well, Aunt Dicey, why did you take the name of Jane Callender if your name is really Dicey Fairfax?”

“W’y, I done tol’ you, Bobby, dat Sis’ Jane Callender was des’ my bus’ness name.”

“Well, how were you to use this business name?”

“Well, it was des dis away. Sis’ Jane Callender, she gwine git huh pension, but la, chile, she tuk down sick unto deaf, an’ Brothah Buford, he say dat she ought to mek a will in favoh of somebody, so’s de money would stay ‘mongst ouah folks, an’ so, bimeby, she ‘greed she mek a will.”

“And who is Brother Buford, Aunt Dicey?”

“Brothah Buford? Oh, he’s de gemman whut come an’ offered to ‘ten’ to Sis’ Jane Callender’s bus’ness fu’ huh. He’s a moughty clevah man.”

“And he told her she ought to make a will?”

“Yas, suh. So she ‘greed she gwine mek a will, an’ she say to me, ‘Sis Dicey, you sut’ny has been good to me sence I been layin’ hyeah on dis bed of ‘fliction, an’ I gwine will all my proputy to you.’ Well, I don’t want to tek de money, an’ she des mos’ nigh fo’ce it on me, so I say yes, an’ Brothah Buford he des sot an’ talk to us, an’ he say dat he come to-morror to bring a lawyer to draw up de will. But bless Gawd, honey, Sis’ Callender died dat night, an’ de will wasn’t made, so when Brothah Buford come bright an’ early next mornin’, I was layin’ Sis’ Callender out. Brothah Buford was mighty much moved, he was. I nevah did see a strange pusson tek anything so hard in all my life, an’ den he talk to me, an’ he say, ‘Now, Sis’ Dicey, is you notified any de neighbours yit?’ an’ I said no I hain’t notified no one of de neighbours, case I ain’t ‘quainted wid none o’ dem yit, an’ he say, ‘How erbout de doctah? Is he ‘quainted wid de diseased?’ an’ I tol’ him no, he des come in, da’s all. ‘Well,’ he say, ‘cose you un’erstan’ now dat you is Sis’ Jane Callender, caise you inhe’it huh name, an’ when de doctah come to mek out de ‘stiffycate, you mus’ tell him dat Sis’ Dicey Fairfax is de name of de diseased, an’ it’ll be all right, an’ aftah dis you got to go by de name o’ Jane Callender, caise it’s a bus’ness name you done inhe’it.’ Well, dat’s whut I done, an’ dat’s huccome I been Jane Callender in de bus’ness ‘sactions, an’ Dicey Fairfax at home. Now, you un’erstan’, don’t you? It wuz my inhe’ited name.”

“But don’t you know that what you have done is a penitentiary offence?”

“Who you stan’in’ up talkin’ to dat erway, you nasty impident little scoun’el? Don’t you talk to me dat erway. I reckon ef yo’ mammy was hyeah she sut’ny would tend to yo’ case. You alluse was sassier an’ pearter den yo’ brother Nelse, an’ he had to go an’ git killed in de wah, an’ you—you—w’y, jedge, I’se spanked dat boy mo’ times den I kin tell you fu’ hus impidence. I don’t see how you evah gits erlong wid him.”

The court repressed a ripple that ran around. But there was no smile on the smooth-shaven, clear-cut face of the young Southerner. Turning to the attorney for the defence, he said: “Will you take the witness?” But that gentleman, waving one helpless hand, shook his head.

“That will do, then,” said young Fairfax. “Your Honor,” he went on, addressing the court, “I have no desire to prosecute this case further. You all see the trend of it just as I see, and it would be folly to continue the examination of any of the rest of these witnesses. We have got that story from Aunt Dicey herself as straight as an arrow from a bow. While technically she is guilty; while according to the facts she is a criminal according to the motive and the intent of her actions, she is as innocent as the whitest soul among us.” He could not repress the youthful Southerner’s love for this little bit of rhetoric.

“And I believe that nothing is to be gained by going further into the matter, save for the purpose of finding out the whereabouts of this Brother Buford, and attending to his case as the facts warrant. But before we do this, I want to see the stamp of crime wiped away from the name of my Aunt Dicey there, and I beg leave of the court to enter a nolle prosse. There is only one other thing I must ask of Aunt Dicey, and that is that she return the money that was illegally gotten, and give us information concerning the whereabouts of Buford.”

Aunt Dicey looked up in excitement, “W’y, chile, ef dat money was got illegal, I don’ want it, but I do know whut I gwine to do, cause I done ‘vested it all wid Brothah Buford in his colorednization comp’ny.” The court drew its breath. It had been expecting some such dénouement.

“And where is the office of this company situated?”

“Well, I des can’t tell dat,” said the old lady. “W’y, la, man, Brothah Buford was in co’t to-day. Whaih is he? Brothah Buford, whaih you?” But no answer came from the surrounding spectators. Brother Buford had faded away. The old lady, however, after due conventions, was permitted to go home.

It was with joy in her heart that Aunt Dicey Fairfax went back to her little cottage after her dismissal, but her face clouded when soon after Robert Fairfax came in.

“Hyeah you come as usual,” she said with well-feigned anger. “Tryin’ to sof’ soap me aftah you been carryin’ on. You ain’t changed one mite fu’ all yo’ bein’ a man. What you talk to me dat away in co’t fu’?”

Fairfax’s face was very grave. “It was necessary, Aunt Dicey,” he said. “You know I’m a lawyer now, and there are certain things that lawyers have to do whether they like it or not. You don’t understand. That man Buford is a scoundrel, and he came very near leading you into a very dangerous and criminal act. I am glad I was near to save you.”

“Oh, honey, chile, I didn’t know dat. Set down an’ tell me all erbout it.”

This the attorney did, and the old lady’s indignation blazed forth. “Well, I hope to de Lawd you’ll fin’ dat rascal an’ larrup him ontwell he cain’t stan’ straight.”

“No, we’re going to do better than that and a great deal better. If we find him we are going to send him where he won’t inveigle any more innocent people into rascality, and you’re going to help us.”

“W’y, sut’ny, chile, I’ll do all I kin to he’p you git dat rascal, but I don’t know whaih he lives, case he’s allus come hyeah to see me.”

“He’ll come back some day. In the meantime we will be laying for him.”

Aunt Dicey was putting some very flaky biscuits into the oven, and perhaps the memory of other days made the young lawyer prolong his visit and his explanation. When, however, he left, it was with well-laid plans to catch Jason Buford napping.

It did not take long. Stealthily that same evening a tapping came at Aunt Dicey’s door. She opened it, and a small, crouching figure crept in. It was Mr. Buford. He turned down the collar of his coat which he had had closely up about his face and said:

“Well, well, Sis’ Callender, you sut’ny have spoiled us all.”

“La, Brothah Buford, come in hyeah an’ set down. Whaih you been?”

“I been hidin’ fu’ feah of that testimony you give in the court room. What did you do that fu’?”

“La, me, I didn’t know, you didn’t ‘splain to me in de fust.”

“Well, you see, you spoiled it, an’ I’ve got to git out of town as soon as I kin. Sis’ Callender, dese hyeah white people is mighty slippery, and they might catch me. But I want to beg you to go on away from hyeah so’s you won’t be hyeah to testify if dey does. Hyeah’s a hundred dollars of yo’ money right down, and you leave hyeah to-morrer mornin’ an’ go erway as far as you kin git.”

“La, man, I’s puffectly willin’ to he’p you, you know dat.”

“Cose, cose,” he answered hurriedly, “we col’red people has got to stan’ together.”

“But what about de res’ of dat money dat I been ‘vestin’ wid you?”

“I’m goin’ to pay intrus’ on that,” answered the promoter glibly.

“All right, all right.” Aunt Dicey had made several trips to the little back room just off her sitting room as she talked with the promoter. Three times in the window had she waved a lighted lamp. Three times without success. But at the last “all right,” she went into the room again. This time the waving lamp was answered by the sudden flash of a lantern outside.

“All right,” she said, as she returned to the room, “set down an’ lemme fix you some suppah.”

“I ain’t hardly got the time. I got to git away from hyeah.” But the smell of the new baked biscuits was in his nostrils and he could not resist the temptation to sit down. He was eating hastily, but with appreciation, when the door opened and two minions of the law entered.

Buford sprang up and turned to flee, but at the back door, her large form a towering and impassive barrier, stood Aunt Dicey.

“Oh, don’t hu’y, Brothah Buford,” she said calmly, “set down an’ he’p yo’se’f. Dese hyeah’s my friends.”

It was the next day that Robert Fairfax saw him in his cell. The man’s face was ashen with coward’s terror. He was like a caught rat though, bitingly on the defensive.

“You see we’ve got you, Buford,” said Fairfax coldly to him. “It is as well to confess.”

“I ain’t got nothin’ to say,” said Buford cautiously.

“You will have something to say later on unless you say it now. I don’t want to intimidate you, but Aunt Dicey’s word will be taken in any court in the United States against yours, and I see a few years hard labour for you between good stout walls.”

The little promoter showed his teeth in an impotent snarl. “What do you want me to do?” he asked, weakening.

“First, I want you to give back every cent of the money that you got out of Dicey Fairfax. Second, I want you to give up to every one of those Negroes that you have cheated every cent of the property you have accumulated by fraudulent means. Third, I want you to leave this place, and never come back so long as God leaves breath in your dirty body. If you do this, I will save you—you are not worth the saving—from the pen or worse. If you don’t, I will make this place so hot for you that hell will seem like an icebox beside it.”

The little yellow man was cowering in his cell before the attorney’s indignation. His lips were drawn back over his teeth in something that was neither a snarl nor a smile. His eyes were bulging and fear-stricken, and his hands clasped and unclasped themselves nervously.

“I—I——” he faltered, “do you want to send me out without a cent?”

“Without a cent, without a cent,” said Fairfax tensely.

“I won’t do it,” the rat in him again showed fight. “I won’t do it. I’ll stay hyeah an’ fight you. You can’t prove anything on me.”

“All right, all right,” and the attorney turned toward the door.

“Wait, wait,” called the man, “I will do it, my God! I will do it. Jest let me out o’ hyeah, don’t keep me caged up. I’ll go away from hyeah.”

Fairfax turned back to him coldly, “You will keep your word?”

“Yes.”

“I will return at once and take the confession.”

And so the thing was done. Jason Buford, stripped of his ill-gotten gains, left the neighbourhood of Little Africa forever. And Aunt Dicey, no longer a wealthy woman and a capitalist, is baking golden brown biscuits for a certain young attorney and his wife, who has the bad habit of rousing her anger by references to her business name and her investments with a promoter.

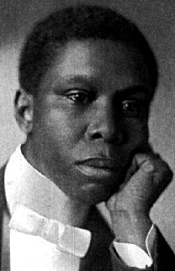

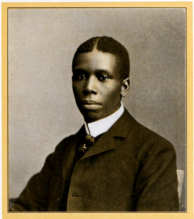

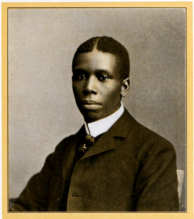

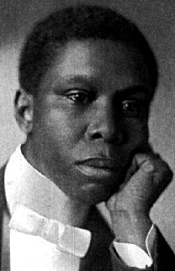

Paul Laurence Dunbar

(1872 – 1906)

The Promotor

From The Heart Of Happy Hollow, a collection of short stories reprinted in 1904 by Dodd, Mead and Company, New York.

Short Story

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive C-D, Archive C-D, Dunbar, Paul Laurence, Dunbar, Paul Laurence, Paul Laurence Dunbar, Paul Laurence Dunbar

THE SCAPEGOAT (II)

A year is not a long time. It was short enough to prevent people from forgetting Robinson, and yet long enough for their pity to grow strong as they remembered. Indeed, he was not gone a year. Good behaviour cut two months off the time of his sentence, and by the time people had come around to the notion that he was really the greatest and smartest man in Cadgers he was at home again.

He came back with no flourish of trumpets, but quietly, humbly. He went back again into the heart of the black district. His business had deteriorated during his absence, but he put new blood and new life into it. He did not go to work in the shop himself, but, taking down the shingle that had swung idly before his office door during his imprisonment, he opened the little room as a news- and cigar-stand.

He came back with no flourish of trumpets, but quietly, humbly. He went back again into the heart of the black district. His business had deteriorated during his absence, but he put new blood and new life into it. He did not go to work in the shop himself, but, taking down the shingle that had swung idly before his office door during his imprisonment, he opened the little room as a news- and cigar-stand.

Here anxious, pitying custom came to him and he prospered again. He was very quiet. Uptown hardly knew that he was again in Cadgers, and it knew nothing whatever of his doings.

“I wonder why Asbury is so quiet,” they said to one another. “It isn’t like him to be quiet.” And they felt vaguely uneasy about him.

So many people had begun to say, “Well, he was a mighty good fellow after all.”

Mr. Bingo expressed the opinion that Asbury was quiet because he was crushed, but others expressed doubt as to this. There are calms and calms, some after and some before the storm. Which was this?

They waited a while, and, as no storm came, concluded that this must be the after-quiet. Bingo, reassured, volunteered to go and seek confirmation of this conclusion.

He went, and Asbury received him with an indifferent, not to say, impolite, demeanour.

“Well, we’re glad to see you back, Asbury,” said Bingo patronisingly. He had variously demonstrated his inability to lead during his rival’s absence and was proud of it. “What are you going to do?”

“I’m going to work.”

“That’s right. I reckon you’ll stay out of politics.”

“What could I do even if I went in?”

“Nothing now, of course; but I didn’t know—-“

He did not see the gleam in Asbury’s half shut eyes. He only marked his humility, and he went back swelling with the news.

“Completely crushed–all the run taken out of him,” was his report.

The black district believed this, too, and a sullen, smouldering anger took possession of them. Here was a good man ruined. Some of the people whom he had helped in his former days–some of the rude, coarse people of the low quarter who were still sufficiently unenlightened to be grateful–talked among themselves and offered to get up a demonstration for him. But he denied them. No, he wanted nothing of the kind. It would only bring him into unfavourable notice. All he wanted was that they would always be his friends and would stick by him.

They would to the death.

There were again two factions in Cadgers. The school-master could not forget how once on a time he had been made a tool of by Mr. Bingo. So he revolted against his rule and set himself up as the leader of an opposing clique. The fight had been long and strong, but had ended with odds slightly in Bingo’s favour.

But Mr. Morton did not despair. As the first of January and Emancipation Day approached, he arrayed his hosts, and the fight for supremacy became fiercer than ever. The school-teacher is giving you a pretty hard brought the school-children in for chorus singing, secured an able orator, and the best essayist in town. With all this, he was formidable.

Mr. Bingo knew that he had the fight of his life on his hands, and he entered with fear as well as zest. He, too, found an orator, but he was not sure that he was as good as Morton’s. There was no doubt but that his essayist was not. He secured a band, but still he felt unsatisfied. He had hardly done enough, and for the school-master to beat him now meant his political destruction.

It was in this state of mind that he was surprised to receive a visit from Mr. Asbury.

“I reckon you’re surprised to see me here,” said Asbury, smiling.

“I am pleased, I know.” Bingo was astute.

“Well, I just dropped in on business.”

“To be sure, to be sure, Asbury. What can I do for you?”

“It’s more what I can do for you that I came to talk about,” was the reply.

“I don’t believe I understand you.”

“Well, it’s plain enough. They say that the school-teacher is giving you a pretty hard fight.”

“Oh, not so hard.”

“No man can be too sure of winning, though. Mr. Morton once did me a mean turn when he started the faction against me.”

Bingo’s heart gave a great leap, and then stopped for the fraction of a second.

“You were in it, of course,” pursued Asbury, “but I can look over your part in it in order to get even with the man who started it.”

It was true, then, thought Bingo gladly. He did not know. He wanted revenge for his wrongs and upon the wrong man. How well the schemer had covered his tracks! Asbury should have his revenge and Morton would be the sufferer.

“Of course, Asbury, you know what I did I did innocently.”

“Oh, yes, in politics we are all lambs and the wolves are only to be found in the other party. We’ll pass that, though. What I want to say is that I can help you to make your celebration an overwhelming success. I still have some influence down in my district.”

“Certainly, and very justly, too. Why, I should be delighted with your aid. I could give you a prominent place in the procession.”

“I don’t want it; I don’t want to appear in this at all. All I want is revenge. You can have all the credit, but let me down my enemy.”

Bingo was perfectly willing, and, with their heads close together, they had a long and close consultation. When Asbury was gone, Mr. Bingo lay back in his chair and laughed. “I’m a slick duck,” he said.

From that hour Mr. Bingo’s cause began to take on the appearance of something very like a boom. More bands were hired. The interior of the State was called upon and a more eloquent orator secured. The crowd hastened to array itself on the growing side.

With surprised eyes, the school-master beheld the wonder of it, but he kept to his own purpose with dogged insistence, even when he saw that he could not turn aside the overwhelming defeat that threatened him. But in spite of his obstinacy, his hours were dark and bitter. Asbury worked like a mole, all underground, but he was indefatigable. Two days before the celebration time everything was perfected for the biggest demonstration that Cadgers had ever known. All the next day and night he was busy among his allies.

On the morning of the great day, Mr. Bingo, wonderfully caparisoned, rode down to the hall where the parade was to form. He was early. No one had yet come. In an hour a score of men all told had collected. Another hour passed, and no more had come. Then there smote upon his ear the sound of music. They were coming at last. Bringing his sword to his shoulder, he rode forward to the middle of the street. Ah, there they were. But–but–could he believe his eyes? They were going in another direction, and at their head rode–Morton! He gnashed his teeth in fury. He had been led into a trap and betrayed. The procession passing had been his–all his. He heard them cheering, and then, oh! climax of infidelity, he saw his own orator go past in a carriage, bowing and smiling to the crowd.

There was no doubting who had done this thing. The hand of Asbury was apparent in it. He must have known the truth all along, thought Bingo. His allies left him one by one for the other hall, and he rode home in a humiliation deeper than he had ever known before.

Asbury did not appear at the celebration. He was at his little news-stand all day.

In a day or two the defeated aspirant had further cause to curse his false friend. He found that not only had the people defected from him, but that the thing had been so adroitly managed that he appeared to be in fault, and three-fourths of those who knew him were angry at some supposed grievance. His cup of bitterness was full when his partner, a quietly ambitious man, suggested that they dissolve their relations.

His ruin was complete.

The lawyer was not alone in seeing Asbury’s hand in his downfall. The party managers saw it too, and they met together to discuss the dangerous factor which, while it appeared to slumber, was so terribly awake. They decided that he must be appeased, and they visited him.

He was still busy at his news-stand. They talked to him adroitly, while he sorted papers and kept an impassive face. When they were all done, he looked up for a moment and replied, “You know, gentlemen, as an ex-convict I am not in politics.”

Some of them had the grace to flush.

“But you can use your influence,” they said.

“I am not in politics,” was his only reply.

And the spring elections were coming on. Well, they worked hard, and he showed no sign. He treated with neither one party nor the other. “Perhaps,” thought the managers, “he is out of politics,” and they grew more confident.

It was nearing eleven o’clock on the morning of election when a cloud no bigger than a man’s hand appeared upon the horizon. It came from the direction of the black district. It grew, and the managers of the party in power looked at it, fascinated by an ominous dread. Finally it began to rain Negro voters, and as one man they voted against their former candidates. Their organisation was perfect. They simply came, voted, and left, but they overwhelmed everything. Not one of the party that had damned Robinson Asbury was left in power save old Judge Davis. His majority was overwhelming.

The generalship that had engineered the thing was perfect. There were loud threats against the newsdealer. But no one bothered him except a reporter. The reporter called to see just how it was done. He found Asbury very busy sorting papers. To the newspaper man’s questions he had only this reply, “I am not in politics, sir.”

But Cadgers had learned its lesson.

Paul Laurence Dunbar

(1872 – 1906)

The Scapegoat (II)

Short story

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive C-D, Archive C-D, Dunbar, Paul Laurence, Dunbar, Paul Laurence, Paul Laurence Dunbar, Paul Laurence Dunbar

THE SCAPEGOAT (I)

The law is usually supposed to be a stern mistress, not to be lightly wooed, and yielding only to the most ardent pursuit. But even law, like love, sits more easily on some natures than on others.

This was the case with Mr. Robinson Asbury. Mr. Asbury had started life as a bootblack in the growing town of Cadgers. From this he had risen one step and become porter and messenger in a barber-shop. This rise fired his ambition, and he was not content until he had learned to use the shears and the razor and had a chair of his own. From this, in a man of Robinson’s temperament, it was only a step to a shop of his own, and he placed it where it would do the most good.

This was the case with Mr. Robinson Asbury. Mr. Asbury had started life as a bootblack in the growing town of Cadgers. From this he had risen one step and become porter and messenger in a barber-shop. This rise fired his ambition, and he was not content until he had learned to use the shears and the razor and had a chair of his own. From this, in a man of Robinson’s temperament, it was only a step to a shop of his own, and he placed it where it would do the most good.

Fully one-half of the population of Cadgers was composed of Negroes, and with their usual tendency to colonise, a tendency encouraged, and in fact compelled, by circumstances, they had gathered into one part of the town. Here in alleys, and streets as dirty and hardly wider, they thronged like ants.

It was in this place that Mr. Asbury set up his shop, and he won the hearts of his prospective customers by putting up the significant sign, “Equal Rights Barber-Shop.” This legend was quite unnecessary, because there was only one race about, to patronise the place. But it was a delicate sop to the people’s vanity, and it served its purpose.

Asbury came to be known as a clever fellow, and his business grew. The shop really became a sort of club, and, on Saturday nights especially, was the gathering-place of the men of the whole Negro quarter. He kept the illustrated and race journals there, and those who cared neither to talk nor listen to someone else might see pictured the doings of high society in very short skirts or read in the Negro papers how Miss Boston had entertained Miss Blueford to tea on such and such an afternoon. Also, he kept the policy returns, which was wise, if not moral.

It was his wisdom rather more than his morality that made the party managers after a while cast their glances toward him as a man who might be useful to their interests. It would be well to have a man–a shrewd, powerful man–down in that part of the town who could carry his people’s vote in his vest pocket, and who at any time its delivery might be needed, could hand it over without hesitation. Asbury seemed that man, and they settled upon him. They gave him money, and they gave him power and patronage. He took it all silently and he carried out his bargain faithfully. His hands and his lips alike closed tightly when there was anything within them. It was not long before he found himself the big Negro of the district and, of necessity, of the town. The time came when, at a critical moment, the managers saw that they had not reckoned without their host in choosing this barber of the black district as the leader of his people.

Now, so much success must have satisfied any other man. But in many ways Mr. Asbury was unique. For a long time he himself had done very little shaving–except of notes, to keep his hand in. His time had been otherwise employed. In the evening hours he had been wooing the coquettish Dame Law, and, wonderful to say, she had yielded easily to his advances.

It was against the advice of his friends that he asked for admission to the bar. They felt that he could do more good in the place where he was.

“You see, Robinson,” said old Judge Davis, “it’s just like this: If you’re not admitted, it’ll hurt you with the people; if you are admitted, you’ll move uptown to an office and get out of touch with them.”

Asbury smiled an inscrutable smile. Then he whispered something into the judge’s ear that made the old man wrinkle from his neck up with appreciative smiles.

“Asbury,” he said, “you are–you are–well, you ought to be white, that’s all. When we find a black man like you we send him to State’s prison. If you were white, you’d go to the Senate.”

The Negro laughed confidently.

He was admitted to the bar soon after, whether by merit or by connivance is not to be told.

“Now he will move uptown,” said the black community. “Well, that’s the way with a coloured man when he gets a start.”

But they did not know Asbury Robinson yet. He was a man of surprises, and they were destined to disappointment. He did not move uptown. He built an office in a small open space next his shop, and there hung out his shingle.

“I will never desert the people who have done so much to elevate me,” said Mr. Asbury.

“I will live among them and I will die among them.”

This was a strong card for the barber-lawyer. The people seized upon the statement as expressing a nobility of an altogether unique brand.

They held a mass meeting and indorsed him. They made resolutions that extolled him, and the Negro band came around and serenaded him, playing various things in varied time.

All this was very sweet to Mr. Asbury, and the party managers chuckled with satisfaction and said, “That Asbury, that Asbury!”

Now there is a fable extant of a man who tried to please everybody, and his failure is a matter of record. Robinson Asbury was not more successful. But be it said that his ill success was due to no fault or shortcoming of his.

For a long time his growing power had been looked upon with disfavour by the coloured law firm of Bingo & Latchett. Both Mr. Bingo and Mr. Latchett themselves aspired to be Negro leaders in Cadgers, and they were delivering Emancipation Day orations and riding at the head of processions when Mr. Asbury was blacking boots. Is it any wonder, then, that they viewed with alarm his sudden rise? They kept their counsel, however, and treated with him, for it was best. They allowed him his scope without open revolt until the day upon which he hung out his shingle. This was the last straw. They could stand no more. Asbury had stolen their other chances from them, and now he was poaching upon the last of their preserves. So Mr. Bingo and Mr. Latchett put their heads together to plan the downfall of their common enemy.

The plot was deep and embraced the formation of an opposing faction made up of the best Negroes of the town. It would have looked too much like what it was for the gentlemen to show themselves in the matter, and so they took into their confidence Mr. Isaac Morton, the principal of the coloured school, and it was under his ostensible leadership that the new faction finally came into being.

Mr. Morton was really an innocent young man, and he had ideals which should never have been exposed to the air. When the wily confederates came to him with their plan he believed that his worth had been recognised, and at last he was to be what Nature destined him for–a leader.

The better class of Negroes–by that is meant those who were particularly envious of Asbury’s success–flocked to the new man’s standard. But whether the race be white or black, political virtue is always in a minority, so Asbury could afford to smile at the force arrayed against him.

The new faction met together and resolved. They resolved, among other things, that Mr. Asbury was an enemy to his race and a menace to civilisation. They decided that he should be abolished; but, as they couldn’t get out an injunction against him, and as he had the whole undignified but still voting black belt behind him, he went serenely on his way.

“They’re after you hot and heavy, Asbury,” said one of his friends to him.

“Oh, yes,” was the reply, “they’re after me, but after a while I’ll get so far away that they’ll be running in front.”

“It’s all the best people, they say.”

“Yes. Well, it’s good to be one of the best people, but your vote only counts one just the same.”

The time came, however, when Mr. Asbury’s theory was put to the test. The Cadgerites celebrated the first of January as Emancipation Day. On this day there was a large procession, with speechmaking in the afternoon and fireworks at night. It was the custom to concede the leadership of the coloured people of the town to the man who managed to lead the procession. For two years past this honour had fallen, of course, to Robinson Asbury, and there had been no disposition on the part of anybody to try conclusions with him.

Mr. Morton’s faction changed all this. When Asbury went to work to solicit contributions for the celebration, he suddenly became aware that he had a fight upon his hands. All the better-class Negroes were staying out of it. The next thing he knew was that plans were on foot for a rival demonstration.

“Oh,” he said to himself, “that’s it, is it? Well, if they want a fight they can have it.”

He had a talk with the party managers, and he had another with Judge Davis.

“All I want is a little lift, judge,” he said, “and I’ll make ’em think the sky has turned loose and is vomiting niggers.”

The judge believed that he could do it. So did the party managers. Asbury got his lift. Emancipation Day came.

There were two parades. At least, there was one parade and the shadow of another. Asbury’s, however, was not the shadow. There was a great deal of substance about it–substance made up of many people, many banners, and numerous bands. He did not have the best people. Indeed, among his cohorts there were a good many of the pronounced rag-tag and bobtail. But he had noise and numbers. In such cases, nothing more is needed. The success of Asbury’s side of the affair did everything to confirm his friends in their good opinion of him.

When he found himself defeated, Mr. Silas Bingo saw that it would be policy to placate his rival’s just anger against him. He called upon him at his office the day after the celebration.

“Well, Asbury,” he said, “you beat us, didn’t you?”

“It wasn’t a question of beating,” said the other calmly. “It was only an inquiry as to who were the people–the few or the many.”

“Well, it was well done, and you’ve shown that you are a manager. I confess that I haven’t always thought that you were doing the wisest thing in living down here and catering to this class of people when you might, with your ability, to be much more to the better class.”

“What do they base their claims of being better on?”

“Oh, there ain’t any use discussing that. We can’t get along without you, we see that. So I, for one, have decided to work with you for harmony.”

“Harmony. Yes, that’s what we want.”

“If I can do anything to help you at any time, why you have only to command me.”

“I am glad to find such a friend in you. Be sure, if I ever need you, Bingo, I’ll call on you.”

“And I’ll be ready to serve you.”

Asbury smiled when his visitor was gone. He smiled, and knitted his brow. “I wonder what Bingo’s got up his sleeve,” he said. “He’ll bear watching.”

It may have been pride at his triumph, it may have been gratitude at his helpers, but Asbury went into the ensuing campaign with reckless enthusiasm. He did the most daring things for the party’s sake. Bingo, true to his promise, was ever at his side ready to serve him. Finally, association and immunity made danger less fearsome; the rival no longer appeared a menace.

With the generosity born of obstacles overcome, Asbury determined to forgive Bingo and give him a chance. He let him in on a deal, and from that time they worked amicably together until the election came and passed.

It was a close election and many things had had to be done, but there were men there ready and waiting to do them. They were successful, and then the first cry of the defeated party was, as usual, “Fraud! Fraud!” The cry was taken up by the jealous, the disgruntled, and the virtuous.

Someone remembered how two years ago the registration books had been stolen. It was known upon good authority that money had been freely used. Men held up their hands in horror at the suggestion that the Negro vote had been juggled with, as if that were a new thing. From their pulpits ministers denounced the machine and bade their hearers rise and throw off the yoke of a corrupt municipal government. One of those sudden fevers of reform had taken possession of the town and threatened to destroy the successful party.

They began to look around them. They must purify themselves. They must give the people some tangible evidence of their own yearnings after purity. They looked around them for a sacrifice to lay upon the altar of municipal reform. Their eyes fell upon Mr. Bingo. No, he was not big enough. His blood was too scant to wash away the political stains. Then they looked into each other’s eyes and turned their gaze away to let it fall upon Mr. Asbury. They really hated to do it. But there must be a scapegoat. The god from the Machine commanded them to slay him.

Robinson Asbury was charged with many crimes–with all that he had committed and some that he had not. When Mr. Bingo saw what was afoot he threw himself heart and soul into the work of his old rival’s enemies. He was of incalculable use to them.

Judge Davis refused to have anything to do with the matter. But in spite of his disapproval it went on. Asbury was indicted and tried. The evidence was all against him, and no one gave more damaging testimony than his friend, Mr. Bingo. The judge’s charge was favourable to the defendant, but the current of popular opinion could not be entirely stemmed. The jury brought in a verdict of guilty.

“Before I am sentenced, judge, I have a statement to make to the court. It will take less than ten minutes.”

“Go on, Robinson,” said the judge kindly.

Asbury started, in a monotonous tone, a recital that brought the prosecuting attorney to his feet in a minute. The judge waved him down, and sat transfixed by a sort of fascinated horror as the convicted man went on. The before-mentioned attorney drew a knife and started for the prisoner’s dock. With difficulty he was restrained. A dozen faces in the court-room were red and pale by turns.

“He ought to be killed,” whispered Mr. Bingo audibly.

Robinson Asbury looked at him and smiled, and then he told a few things of him. He gave the ins and outs of some of the misdemeanours of which he stood accused. He showed who were the men behind the throne. And still, pale and transfixed, Judge Davis waited for his own sentence.

Never were ten minutes so well taken up. It was a tale of rottenness and corruption in high places told simply and with the stamp of truth upon it.

He did not mention the judge’s name. But he had torn the mask from the face of every other man who had been concerned in his downfall. They had shorn him of his strength, but they had forgotten that he was yet able to bring the roof and pillars tumbling about their heads.

The judge’s voice shook as he pronounced sentence upon his old ally–a year in State’s prison.

Some people said it was too light, but the judge knew what it was to wait for the sentence of doom, and he was grateful and sympathetic.

When the sheriff led Asbury away the judge hastened to have a short talk with him.

“I’m sorry, Robinson,” he said, “and I want to tell you that you were no more guilty than the rest of us. But why did you spare me?”

“Because I knew you were my friend,” answered the convict.

“I tried to be, but you were the first man that I’ve ever known since I’ve been in politics who ever gave me any decent return for friendship.”

“I reckon you’re about right, judge.”

In politics, party reform usually lies in making a scapegoat of someone who is only as criminal as the rest, but a little weaker. Asbury’s friends and enemies had succeeded in making him bear the burden of all the party’s crimes, but their reform was hardly a success, and their protestations of a change of heart were received with doubt. Already there were those who began to pity the victim and to say that he had been hardly dealt with.

Mr. Bingo was not of these; but he found, strange to say, that his opposition to the idea went but a little way, and that even with Asbury out of his path he was a smaller man than he was before. Fate was strong against him. His poor, prosperous humanity could not enter the lists against a martyr. Robinson Asbury was now a martyr.

Paul Laurence Dunbar

(1872 – 1906)

The Scapegoat (I)

Short story

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive C-D, Archive C-D, Dunbar, Paul Laurence, Dunbar, Paul Laurence, Paul Laurence Dunbar, Paul Laurence Dunbar

A MATTER OF DOCTRINE

There was great excitement in Miltonville over the advent of a most eloquent and convincing minister from the North.

The beauty about the Rev. Thaddeus Warwick was that he was purely and simply a man of the doctrine. He had no emotions, his sermons were never matters of feeling; but he insisted so strongly upon the constant presentation of the tenets of his creed that his presence in a town was always marked by the enthusiasm and joy of religious disputation.

The beauty about the Rev. Thaddeus Warwick was that he was purely and simply a man of the doctrine. He had no emotions, his sermons were never matters of feeling; but he insisted so strongly upon the constant presentation of the tenets of his creed that his presence in a town was always marked by the enthusiasm and joy of religious disputation.

The Rev. Jasper Hayward, coloured, was a man quite of another stripe. With him it was not so much what a man held as what he felt. The difference in their characteristics, however, did not prevent him from attending Dr. Warwick’s series of sermons, where, from the vantage point of the gallery, he drank in, without assimilating, that divine’s words of wisdom.

Especially was he edified on the night that his white brother held forth upon the doctrine of predestination. It was not that he understood it at all, but that it sounded well and the words had a rich ring as he champed over them again and again.

Mr. Hayward was a man for the time and knew that his congregation desired something new, and if he could supply it he was willing to take lessons even from a white co-worker who had neither “de spi’it ner de fiah.” Because, as he was prone to admit to himself, “dey was sump’in’ in de unnerstannin’.”

He had no idea what plagiarism is, and without a single thought of wrong, he intended to reproduce for his people the religious wisdom which he acquired at the white church. He was an innocent beggar going to the doors of the well-provided for cold spiritual victuals to warm over for his own family. And it would not be plagiarism either, for this very warming-over process would save it from that and make his own whatever he brought. He would season with the pepper of his homely wit, sprinkle it with the salt of his home-made philosophy, then, hot with the fire of his crude eloquence, serve to his people a dish his very own. But to the true purveyor of original dishes it is never pleasant to know that someone else holds the secret of the groundwork of his invention.

It was then something of a shock to the Reverend Mr. Hayward to be accosted by Isaac Middleton, one of his members, just as he was leaving the gallery on the night of this most edifying of sermons.

Isaac laid a hand upon his shoulder and smiled at him benevolently.

“How do, Brothah Hayward,” he said, “you been sittin’ unner de drippin’s of de gospel, too?”

“Yes, I has been listenin’ to de wo’ds of my fellow-laborah in de vineya’d of de Lawd,” replied the preacher with some dignity, for he saw vanishing the vision of his own glory in a revivified sermon on predestination.

Isaac linked his arm familiarly in his pastor’s as they went out upon the street.

“Well, what you t’ink erbout pre-o’dination an’ fo’-destination any how?”

“It sutny has been pussented to us in a powahful light dis eve’nin’.”

“Well, suh, hit opened up my eyes. I do’ know when I’s hyeahed a sehmon dat done my soul mo’ good.”

“It was a upliftin’ episode.”

“Seem lak ‘co’din’ to de way de brothah ‘lucidated de matter to-night dat evaht’ing done sot out an’ cut an’ dried fu’ us. Well dat’s gwine to he’p me lots.”

“De gospel is allus a he’p.”

“But not allus in dis way. You see I ain’t a eddicated man lak you, Brothah Hayward.”

“We can’t all have de same ‘vantages,” the preacher condescended. “But what I feels, I feels, an’ what I unnerstan’s, I unnerstan’s. The Scripture tell us to get unnerstannin’.”

“Well, dat’s what I’s been a-doin’ to-night. I’s been a-doubtin’ an’ a-doubtin’, a-foolin’ erroun’ an’ wonderin’, but now I unnerstan’.”

“‘Splain yo’se’f, Brothah Middleton,” said the preacher.

“Well, suh, I will to you. You knows Miss Sally Briggs? Huh, what say?”

The Reverend Hayward had given a half discernible start and an exclamation had fallen from his lips.

“What say?” repeated his companion.

“I knows de sistah ve’y well, she bein’ a membah of my flock.”

“Well, I been gwine in comp’ny wit dat ooman fu’ de longes’. You ain’t nevah tasted none o’ huh cookin’, has you?”

“I has ‘sperienced de sistah’s puffo’mances in dat line.”

“She is the cookin’est ooman I evah seed in all my life, but howsomedever, I been gwine all dis time an’ I ain’ nevah said de wo’d. I nevah could git clean erway f’om huh widout somep’n’ drawin’ me back, an’ I didn’t know what hit was.”

The preacher was restless.

“Hit was des dis away, Brothah Hayward, I was allus lingerin’ on de brink, feahful to la’nch away, but now I’s a-gwine to la’nch, case dat all dis time tain’t been nuffin but fo’-destination dat been a-holdin’ me on.”

“Ahem,” said the minister; “we mus’ not be in too big a hu’y to put ouah human weaknesses upon some divine cause.”

“I ain’t a-doin’ dat, dough I ain’t a-sputin’ dat de lady is a mos’ oncommon fine lookin’ pusson.”

“I has only seed huh wid de eye of de spi’it,” was the virtuous answer, “an’ to dat eye all t’ings dat are good are beautiful.”

“Yes, suh, an’ lookin’ wid de cookin’ eye, hit seem lak’ I des fo’destinated fu’ to ma’y dat ooman.”

“You say you ain’t axe huh yit?”

“Not yit, but I’s gwine to ez soon ez evah I gets de chanst now.”

“Uh, huh,” said the preacher, and he began to hasten his steps homeward.

“Seems lak you in a pow’ful hu’y to-night,” said his companion, with some difficulty accommodating his own step to the preacher’s masterly strides. He was a short man and his pastor was tall and gaunt.

“I has somp’n’ on my min,’ Brothah Middleton, dat I wants to thrash out to-night in de sollertude of my own chambah,” was the solemn reply.

“Well, I ain’ gwine keep erlong wid you an’ pestah you wid my chattah, Brothah Hayward,” and at the next corner Isaac Middleton turned off and went his way, with a cheery “so long, may de Lawd set wid you in yo’ meddertations.”

“So long,” said his pastor hastily. Then he did what would be strange in any man, but seemed stranger in so virtuous a minister. He checked his hasty pace, and, after furtively watching Middleton out of sight, turned and retraced his steps in a direction exactly opposite to the one in which he had been going, and toward the cottage of the very Sister Griggs concerning whose charms the minister’s parishioner had held forth.

It was late, but the pastor knew that the woman whom he sought was industrious and often worked late, and with ever increasing eagerness he hurried on. He was fully rewarded for his perseverance when the light from the window of his intended hostess gleamed upon him, and when she stood in the full glow of it as the door opened in answer to his knock.

“La, Brothah Hayward, ef it ain’t you; howdy; come in.”

“Howdy, howdy, Sistah Griggs, how you come on?”

“Oh, I’s des tol’able,” industriously dusting a chair. “How’s yo’se’f?”

“I’s right smaht, thankee ma’am.”

“W’y, Brothah Hayward, ain’t you los’ down in dis paht of de town?”

“No, indeed, Sistah Griggs, de shep’erd ain’t nevah los’ no whaih dey’s any of de flock.” Then looking around the room at the piles of ironed clothes, he added: “You sutny is a indust’ious ooman.”

“I was des ’bout finishin’ up some i’onin’ I had fu’ de white folks,” smiled Sister Griggs, taking down her ironing-board and resting it in the corner. “Allus when I gits thoo my wo’k at nights I’s putty well tiahed out an’ has to eat a snack; set by, Brothah Hayward, while I fixes us a bite.”

“La, sistah, hit don’t skacely seem right fu’ me to be a-comin’ in hyeah lettin’ you fix fu’ me at dis time o’ night, an’ you mighty nigh tuckahed out, too.”

“Tsch, Brothah Hayward, taint no ha’dah lookin’ out fu’ two dan it is lookin’ out fu’ one.”

Hayward flashed a quick upward glance at his hostess’ face and then repeated slowly, “Yes’m, dat sutny is de trufe. I ain’t nevah t’ought o’ that befo’. Hit ain’t no ha’dah lookin’ out fu’ two dan hit is fu’ one,” and though he was usually an incessant talker, he lapsed into a brown study.

Be it known that the Rev. Mr. Hayward was a man of a very level head, and that his bachelorhood was a matter of economy. He had long considered matrimony in the light of a most desirable estate, but one which he feared to embrace until the rewards for his labours began looking up a little better. But now the matter was being presented to him in an entirely different light. “Hit ain’t no ha’dah lookin’ out fu’ two dan fu’ one.” Might that not be the truth after all. One had to have food. It would take very little more to do for two. One had to have a home to live in. The same house would shelter two. One had to wear clothes. Well, now, there came the rub. But he thought of donation parties, and smiled. Instead of being an extravagance, might not this union of two beings be an economy? Somebody to cook the food, somebody to keep the house, and somebody to mend the clothes.

His reverie was broken in upon by Sally Griggs’ voice. “Hit do seem lak you mighty deep in t’ought dis evenin’, Brothah Hayward. I done spoke to you twicet.”

“Scuse me, Sistah Griggs, my min’ has been mighty deeply ‘sorbed in a little mattah o’ doctrine. What you say to me?”

“I say set up to the table an’ have a bite to eat; tain’t much, but ‘sich ez I have’—you know what de ‘postle said.”

The preacher’s eyes glistened as they took in the well-filled board. There was fervour in the blessing which he asked that made amends for its brevity. Then he fell to.

Isaac Middleton was right. This woman was a genius among cooks. Isaac Middleton was also wrong. He, a layman, had no right to raise his eyes to her. She was the prize of the elect, not the quarry of any chance pursuer. As he ate and talked, his admiration for Sally grew as did his indignation at Middleton’s presumption.

Meanwhile the fair one plied him with delicacies, and paid deferential attention whenever he opened his mouth to give vent to an opinion. An admirable wife she would make, indeed.

At last supper was over and his chair pushed back from the table. With a long sigh of content, he stretched his long legs, tilted back and said: “Well, you done settled de case ez fur ez I is concerned.”

“What dat, Brothah Hayward?” she asked.

“Well, I do’ know’s I’s quite prepahed to tell you yit.”

“Hyeah now, don’ you remembah ol’ Mis’ Eve? Taint nevah right to git a lady’s cur’osity riz.”

“Oh, nemmine, nemmine, I ain’t gwine keep yo’ cur’osity up long. You see, Sistah Griggs, you done ‘lucidated one p’int to me dis night dat meks it plumb needful fu’ me to speak.”

She was looking at him with wide open eyes of expectation.

“You made de ’emark to-night, dat it ain’t no ha’dah lookin’ out aftah two dan one.”

“Oh, Brothah Hayward!”

“Sistah Sally, I reckernizes dat, an’ I want to know ef you won’t let me look out aftah we two? Will you ma’y me?”

She picked nervously at her apron, and her eyes sought the floor modestly as she answered, “Why, Brothah Hayward, I ain’t fittin’ fu’ no sich eddicated man ez you. S’posin’ you’d git to be pu’sidin’ elder, er bishop, er somp’n’ er othah, whaih’d I be?”

He waved his hand magnanimously. “Sistah Griggs, Sally, whatevah high place I may be fo’destined to I shall tek my wife up wid me.”

This was enough, and with her hearty yes, the Rev. Mr. Hayward had Sister Sally close in his clerical arms. They were not through their mutual felicitations, which were indeed so enthusiastic as to drown the sound of a knocking at the door and the ominous scraping of feet, when the door opened to admit Isaac Middleton, just as the preacher was imprinting a very decided kiss upon his fiancee’s cheek.

“Wha’—wha'” exclaimed Middleton.

The preacher turned. “Dat you, Isaac?” he said complacently. “You must ‘scuse ouah ‘pearance, we des got ingaged.”

The fair Sally blushed unseen.

“What!” cried Isaac. “Ingaged, aftah what I tol’ you to-night.” His face was a thundercloud.

“Yes, suh.”

“An’ is dat de way you stan’ up fu’ fo’destination?”

This time it was the preacher’s turn to darken angrily as he replied, “Look a-hyeah, Ike Middleton, all I got to say to you is dat whenevah a lady cook to please me lak dis lady do, an’ whenevah I love one lak I love huh, an’ she seems to love me back, I’s a-gwine to pop de question to huh, fo’destination er no fo’destination, so dah!”

The moment was pregnant with tragic possibilities. The lady still stood with bowed head, but her hand had stolen into her minister’s. Isaac paused, and the situation overwhelmed him. Crushed with anger and defeat he turned toward the door.

On the threshold he paused again to say, “Well, all I got to say to you, Hayward, don’ you nevah talk to me no mor’ nuffin’ ’bout doctrine!”

Paul Laurence Dunbar

(1872 – 1906)

A Matter Of Doctrine

From The Heart Of Happy Hollow, a collection of short stories reprinted in 1904 by Dodd, Mead and Company, New York.

Short Story

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: *Archive African American Literature, Archive C-D, Archive C-D, Dunbar, Paul Laurence, Dunbar, Paul Laurence, Paul Laurence Dunbar, Paul Laurence Dunbar

THE INTERFERENCE OF PATSY ANN

Patsy Ann Meriweather would have told you that her father, or more properly her “pappy,” was a “widover,” and she would have added in her sad little voice, with her mournful eyes upon you, that her mother had “bin daid fu’ nigh onto fou’ yeahs.” Then you could have wept for Patsy, for her years were only thirteen now, and since the passing away of her mother she had been the little mother for her four younger brothers and sisters, as well as her father’s house-keeper.

But Patsy Ann never complained; she was quite willing to be all that she had been until such time as Isaac and Dora, Cassie and little John should be old enough to care for themselves, and also to lighten some of her domestic burdens. She had never reckoned upon any other manner of release. In fact her youthful mind was not able to contemplate the possibility of any other manner of change. But the good women of Patsy’s neighbourhood were not the ones to let her remain in this deplorable state of ignorance. She was to be enlightened as to other changes that might take place in her condition, and of the unspeakable horrors that would transpire with them.

But Patsy Ann never complained; she was quite willing to be all that she had been until such time as Isaac and Dora, Cassie and little John should be old enough to care for themselves, and also to lighten some of her domestic burdens. She had never reckoned upon any other manner of release. In fact her youthful mind was not able to contemplate the possibility of any other manner of change. But the good women of Patsy’s neighbourhood were not the ones to let her remain in this deplorable state of ignorance. She was to be enlightened as to other changes that might take place in her condition, and of the unspeakable horrors that would transpire with them.

It was upon the occasion that little John had taken it into his infant head to have the German measles just at the time that Isaac was slowly recovering from the chicken-pox. Patsy Ann’s powers had been taxed to the utmost, and Mrs. Caroline Gibson had been called in from next door to superintend the brewing of the saffron tea, and for the general care of the fretful sufferer.

To Patsy Ann, then, in ominous tone, spoke this oracle. “Patsy Ann, how yo’ pappy doin’ sence Matildy died?” “Matildy” was the deceased wife.

“Oh, he gittin’ ‘long all right. He was mighty broke up at de fus’, but he ‘low now dat de house go on de same’s ef mammy was a-livin’.”

“Oom huh,” disdainfully; “Oom huh. Yo’ mammy bin daid fou’ yeahs, ain’t she?”

“Yes’m; mighty nigh.”

“Oom huh; fou’ yeahs is a mighty long time fu’ a colo’d man to wait; but we’n he do wait dat long, hit’s all de wuss we’n hit do come.”

“Pap bin wo’kin right stiddy at de brick-ya’d,” said Patsy, in loyal defence against some vaguely implied accusation, “an’ he done put some money in de bank.”

“Bad sign, bad sign,” and Mrs. Gibson gave her head a fearsome shake.

But just then the shrill voice of little John calling for attention drew her away and left Patsy Ann to herself and her meditations.

What could this mean?

When that lady had finished ministering to the sick child and returned, Patsy Ann asked her, “Mis’ Gibson, what you mean by sayin’ ‘bad sign, bad sign?'”

Again the oracle shook her head sagely. Then she answered, “Chil’, you do’ know de dev’ment dey is in dis worl’.”

“But,” retorted the child, “my pappy ain’ up to no dev’ment, ‘case he got ‘uligion an’ bin baptised.”

“Oom-m,” groaned Sistah Gibson, “dat don’ mek a bit o’ diffunce. Who is any mo’ ma’yin’ men den de preachahs demse’ves? W’y Brothah ‘Lias Scott done tempted matermony six times a’ready, an’ ‘s lookin’ roun’ fu’ de sebent, an’ he’s a good man, too.”

“Ma’yin’,” said Patsy breathlessly.

“Yes, honey, ma’yin’, an’ I’s afeared yo’ pappy’s got notions in his haid, an’ w’en a widower git gals in his haid dey ain’ no use a-pesterin’ wid ’em, ‘case dey boun’ to have dey way.”

“Ma’yin’,” said Patsy to herself reflectively. “Ma’yin’.” She knew what it meant, but she had never dreamed of the possibility of such a thing in connection with her father. “Ma’yin’,” and yet the idea of it did not seem so very unalluring.

She spoke her thoughts aloud.

“But ef pap ‘u’d ma’y, Mis’ Gibson, den I’d git a chanct to go to school. He allus sayin’ he mighty sorry ’bout me not goin’.”

“Dah now, dah now,” cried the woman, casting a pitying glance at the child, “dat’s de las’ t’ing. He des a feelin’ roun’ now. You po’, ign’ant, mothahless chil’. You ain’ nevah had no step-mothah, an’ you don’ know what hit means.”

“But she’d tek keer o’ the chillen,” persisted Patsy.

“Sich tekin’ keer of ’em ez hit ‘u’d be. She’d keer fu’ ’em to dey graves. Nobody cain’t tell me nuffin ’bout step-mothahs, case I knows ’em. Dey ain’ no ooman goin’ to tek keer o’ nobody else’s chile lak she’d tek keer o’ huh own,” and Patsy felt a choking come into her throat and a tight sensation about her heart while she listened as Mrs. Gibson regaled her with all the choice horrors that are laid at the door of step-mothers.

From that hour on, one settled conviction took shape and possessed Patsy Ann’s mind; never, if she could help it, would she run the risk of having a step-mother. Come what may, let her be compelled to do what she might, let the hope of school fade from her sight forever and a day—but no step-mother should ever cast her baneful shadow over Patsy Ann’s home.

Experience of life had made her wise for her years, and so for the time she said nothing to her father; but she began to watch him with wary eyes, his goings out and his comings in, and to attach new importance to trifles that had passed unnoticed before by her childish mind.

For instance, if he greased or blacked his boots before going out of an evening her suspicions were immediately aroused and she saw dim visions of her father returning, on his arm the terrible ogress whom she had come to know by the name of step-mother.

Mrs. Gibson’s poison had worked well and rapidly. She had thoroughly inoculated the child’s mind with the step-mother virus, but she had not at the same time made the parent widow-proof, a hard thing to do at best. So it came to pass that with a mysterious horror growing within her, Patsy Ann saw her father black his boots more and more often and fare forth o’ nights and Sunday afternoons.

Finally her little heart could contain its sorrow no longer, and one night when he was later than usual she could not sleep. So she slipped out of bed, turned up the light, and waited for him, determined to have it out, then and there.

He came at last and was all surprise to meet the solemn, round eyes of his little daughter staring at him from across the table.

“W’y, lady gal,” he exclaimed, “what you doin’ up at ‘his time?”

“I sat up fu’ you. I got somep’n’ to ax you, pappy.” Her voice quivered and he snuggled her up in his arms.

“What’s troublin’ my little lady gal now? Is de chillen bin bad?”

She laid her head close against his big breast, and the tears would come as she answered, “No, suh; de chillen bin ez good az good could be, but oh, pappy, pappy, is you got gal in yo’ haid an’ a-goin’ to bring me a step-mothah?”

He held her away from him almost harshly and gazed at her as he queried, “W’y, you po’ baby, you! Who’s bin puttin’ dis hyeah foolishness in yo’ haid?” Then his laugh rang out as he patted her head and drew her close to him again. “Ef yo’ pappy do bring a step-mothah into dis house, Gawd knows he’ll bring de right kin’.”

“Dey ain’t no right kin’,” answered Patsy.

“You don’ know, baby; you don’ know. Go to baid an’ don’ worry.”

He sat up a long time watching the candle sputter, then he pulled off his boots and tiptoed to Patsy’s bedside. He leaned over her. “Po’ little baby,” he said; “what do she know about a step-mothah?” And Patsy saw him and heard him, for she was awake then, and far into the night.

In the eyes of the child her father stood convicted. He had “gal in his haid,” and was going to bring her a step-mother; but it would never be; her resolution was taken.

She arose early the next morning and after getting her father off to work as usual, she took the children into hand. First she scrubbed them assiduously, burnishing their brown faces until they shone again. Then she tussled with their refractory locks, and after that she dressed them out in all the bravery of their best clothes.

Meanwhile her tears were falling like rain, though her lips were shut tight. The children off her mind, she turned her attention to her own toilet, which she made with scrupulous care. Then taking a small tin-type of her mother from the bureau drawer, she put it in her bosom, and leading her little brood she went out of the house, locking the door behind her and placing the key, as was her wont, under the door-step.

Outside she stood for a moment or two, undecided, and then with one long, backward glance at her home she turned and went up the street. At the first corner she paused again, spat in her hand and struck the watery globule with her finger. In the direction the most of the spittle flew, she turned. Patsy Ann was fleeing from home and a step-mother, and Fate had decided her direction for her, even as Mrs. Gibson’s counsels had directed her course.