Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

Geluksvogels bevat een keuze uit Luigi Pirandello’s Novellen voor een jaar, in een blinkend nieuwe vertaling van Yond Boeke en Patty Krone.

Pirandello schreef deze opmerkelijk hoogwaardige verzameling verhalen tussen 1894 en 1936. Zijn dood belette hem het project – één novelle voor elke dag van het jaar – te voltooien.

Pirandello schreef deze opmerkelijk hoogwaardige verzameling verhalen tussen 1894 en 1936. Zijn dood belette hem het project – één novelle voor elke dag van het jaar – te voltooien.

De diversiteit van zijn verhalen, die getuigen van groot psychologisch inzicht, een buitengewoon scherp gevoel voor humor en immens mededogen, is exemplarisch voor Pirandello’s enorme veelzijdigheid als schrijver.

Hij voert een breed scala aan markante personages ten tonele: van arme Siciliaanse boeren die tevergeefs strijden tegen de clerus tot wufte stedelingen die verstrikt raken in hun eigen overspel, van een wanhopige patiënt die in een New Yorks ziekenhuis uit het raam springt tot een geëxalteerde actrice die het moet opnemen tegen een vleermuis.

Pirandello laveert virtuoos tussen vlotte dialogen, van weemoed doortrokken landschapsbeschrijvingen en filosofische bespiegelingen over het aardse bestaan. Sommige verhalen blijken ook nu nog verrassend actueel.

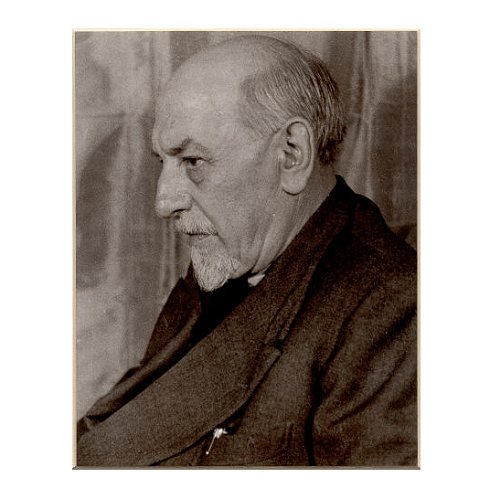

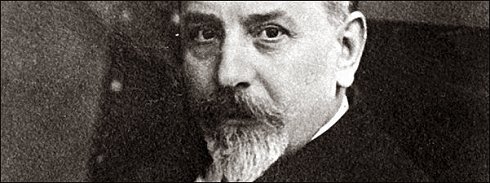

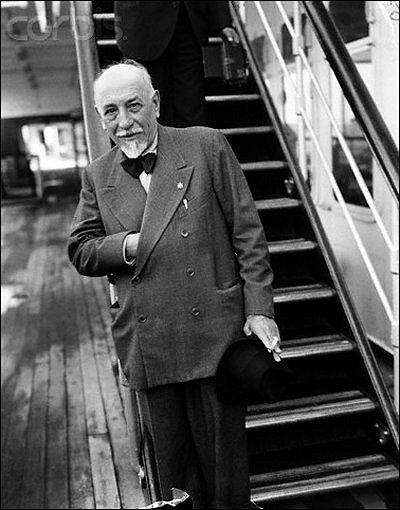

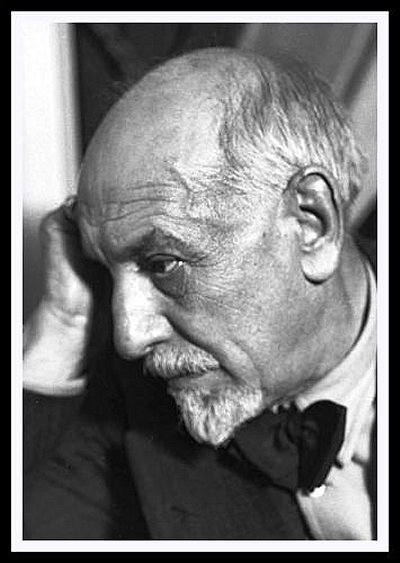

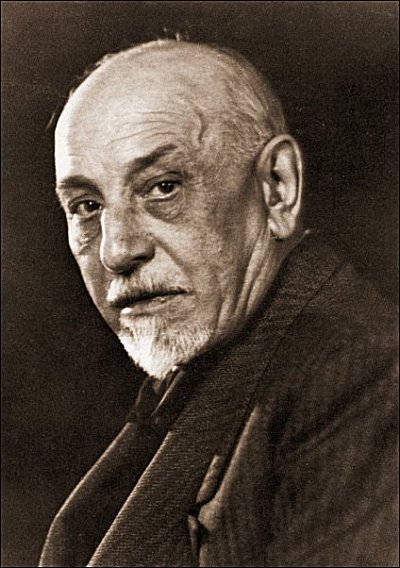

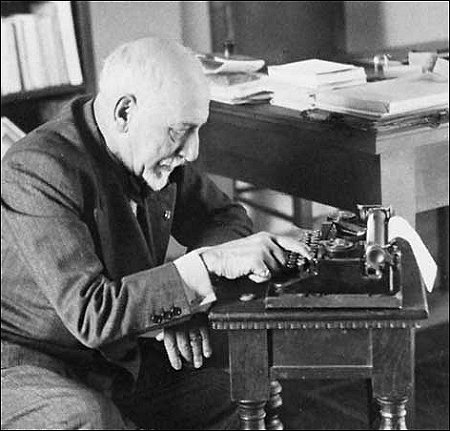

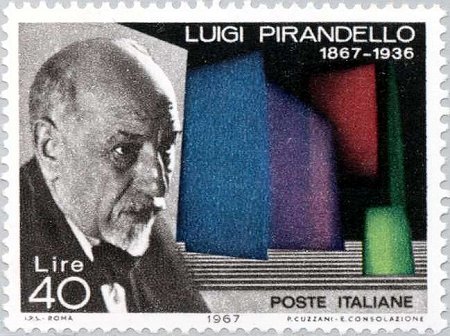

Luigi Pirandello (1867-1936), geboren in een gegoede familie op Sicilië, kreeg in 1934 de Nobelprijs voor de Literatuur. De verfilming van zijn verhalen door Paolo en Vittorio Taviani, Kaos, werd wereldberoemd.

# new translations

# new translations

Geluksvogels Verzamelde verhalen

Auteur: Luigi Pirandello

Taal: Nederlands

Vertaald door Yond Boeke & Patty Krone

Hardcover

Druk: 1 februari 2022

832 pagina’s

ISBN 9789028213142

€ 45,00

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: #Editors Choice Archiv, Archive O-P, Archive O-P, Pirandello, Luigi, Pirandello, Luigi

Luigi Pirandello’s extraordinary final novel begins when Vitangelo Moscarda’s wife remarks that Vitangelo’s nose tilts to the right.

This commonplace interaction spurs the novel’s unemployed, wealthy narrator to examine himself, the way he perceives others, and the ways that others perceive him.

This commonplace interaction spurs the novel’s unemployed, wealthy narrator to examine himself, the way he perceives others, and the ways that others perceive him.

At first he only notices small differences in how he sees himself and how others do; but his self-examination quickly becomes relentless, dizzying, leading to often darkly comic results as Vitangelo decides that he must demolish that version of himself that others see.

Pirandello said of his 1926 novel that it “deals with the disintegration of the personality. It arrives at the most extreme conclusions, the farthest consequences.” Indeed, its unnerving humor and existential dissection of modern identity find counterparts in Samuel Beckett’s Molloy trilogy and the works of Thomas Bernhard and Vladimir Nabokov.

Luigi Pirandello (1867-1936) was an Italian author, who was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1934 for his “bold and brilliant renovation of the drama and the stage.” Pirandello’s works include novels, hundreds of short stories, and plays. Pirandello’s plays are often seen as forerunners for the theatre of the absurd.

One, No One, and One Hundred Thousand

Luigi Pirandello

Translated by William Weaver

Publisher Spurl Editions

Format Paperback

218 pages

ISBN-10 194367907X

ISBN-13 9781943679072

2018

$18.00

# new books

Title One, No One, and One Hundred Thousand

Author Luigi Pirandello

Translated by William Weaver

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Book Stories, Archive O-P, Archive O-P, Luigi Pirandello, Pirandello, Luigi, Pirandello, Luigi, Samuel Beckett, Thomas Bernhard, Vladimir Nabokov

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (35)

Shoot! (Si Gira, 1926)The Notebooks of Serafino Gubbio, Cinematograph Operator by Luigi Pirandello. Translated from the Italian by C. K. Scott Moncrieff

BOOK VII

4

Turn the handle; I have turned it. I have kept my word: to the end. But the vengeance that I sought to accomplish upon the obligation imposed on me, as the slave of a machine, to serve up life to my machine as food, life has chosen to turn back upon me. Very good. No one henceforward can deny that I have now arrived at perfection.

As an operator I am now, truly, perfect.

About a month after the appalling disaster which is still being discussed everywhere, I bring these notes to an end.

A pen and a sheet of paper: there is no other way left to me now in which I can communicate with my fellow-men. I have lost my voice; I am dumb now for ever. Elsewhere in these notes I have written: “I suffer from this silence of mine, into which everyone comes, as into a place of certain hospitality. ‘I should like now my silence to close round me altogether’.” Well, it has closed round me. I could not be better qualified to act as the servant of a machine.

But I must tell you the whole story, as it happened.

The wretched fellow went, next morning, to Borgalli to complain forcibly of the ridiculous figure which, as he was informed, Polacco intended to make him cut with these precautions.

He insisted at all costs that the orders should be cancelled, offering to give them all a specimen, if they needed it, of his well-known skill as a marksman. Polacco excused himself to Borgalli, saying that he had taken these measures not from any want of confidence in Nuti’s courage or sureness of eye, but from prudence, knowing Nuti to be extremely nervous, as for that matter he was shewing himself to be at that moment by uttering this excited protest, instead of the grateful, friendly thanks which Polacco had a right to expect from him.

“Besides,” he unfortunately added, pointing to me, “you see, Commendatore, there’s Gubbio here too, who has to go into the cage….”

The poor wretch looked at me with such contempt that I immediately turned upon Polacco, exclaiming:

“No, no, my dear fellow! Don’t bother about me, please! You know very well that I shall go on quietly turning my handle, even if I see this gentleman in the jaws and claws of the beast!”

There was a laugh from the actors who had gathered round to listen; whereupon Polacco shrugged his shoulders and gave way, or pretended to give way. Fortunately for me, as I learned afterwards, he gave secret instructions to Fantappiè and one of the others to conceal their weapons and to stand ready for any emergency. Nuti went off to his dressing-room to put on his sporting clothes; I went to the Negative Department to prepare my machine for its meal. Fortunately for the company, I drew a much larger supply of film than would be required, to judge approximately by the length of the scene. When I returned to the crowded lawn, by the side of the enormous cage, set with a forest scene, the other cage, with the tiger inside it, had already been carried out and placed so that the two cages opened into one another. It only remained to pull up the door of the smaller cage.

Any number of actors from the four companies had assembled on either side, close to the cage, so that they could see between the tree trunks and branches that concealed its bars. I hoped for a moment that the Nestoroff, having secured her object, would at least have had the prudence not to come. But there she was, alas!

She stood apart from the crowd, a little way off, with Carlo Ferro, dressed in bright green, and was smiling as she repeatedly nodded her head in agreement with what Ferro was saying to her, albeit from the grim attitude in which he stood by her side it seemed evident that such a smile was not the appropriate answer to his words. But it was meant for the others, that smile, for all of us who stood watching her, and was also for me, a brighter smile, when I fixed my gaze on her; and it said to me once again that she was not afraid of anything, because the greatest possible evil for her I already knew: she had it by her side–there it was–Ferro; he was her punishment, and to the very end she I was determined, with that smile, to taste its, full flavour in the coarse words which he was probably addressing to her at that moment.

Taking my eyes from her, I sought those of Nuti. They were clouded. Evidently he too had caught sight of the Nestoroff there in the distance; but he chose to pretend that he had not. His face had grown stiff. He made an effort to smile, but smiled with his lips alone, a faint, nervous smile, at what some one was saying to him. With his black velvet cap on his head, with its long peak, his red coat, a huntsman’s brass horn slung over his shoulder, his white buckskin breeches fitting close to his thighs; booted and spurred, rifle in hand: he was ready.

The door of the big cage, through which ha and I were to enter, was opened from outside; to help us to climb in, two stage hands placed a pair of steps beneath it. He entered the cage first, then I. While I was setting up my machine on its tripod, which had been handed to me through the door of the cage, I noticed that Nuti first of all knelt down on the spot marked out for him, then rose and went across to thrust apart the boughs at one side of the cage, as though he were making a loophole there. I alone was in a position to ask him:

“Why?”

But the state of feeling that had grown up between us did not allow of our exchanging a single word at this stage. His action might therefore have been interpreted by me in several ways, which would have left me uncertain at a moment when the most absolute and precise certainty was essential. And then it was just as though Nuti had not moved at all; not only did I not think any more about his action, it was exactly as though I had not even noticed it.

He took his stand on the spot marked out for him, raising his rifle; I gave the signal:

“Ready.”

We heard from the other cage the sound of the door being pulled up. Polacco, perhaps seeing the animal begin to move towards the open door, shouted amid the silence:

“Are you ready? Shoot!”

And I began to turn the handle, with my eyes on the tree trunks in the background, through which the animal’s head was now protruding, lowered, as though peering out to explore the country; I saw that head slowly drawn back, the two forepaws remain firm, close together, and the hindlegs gradually, silently gather strength and the back rise in an arch in readiness for the spring. My hand was impassively keeping the time that I had set for its movement, faster, slower, dead slow, as though my will had flowed down–firm, lucid, inflexible–into my wrist, and from there had assumed entire control, leaving my brain free to think, my heart to feel; so that my hand continued to obey even when with a pang of terror I saw Nuti take his aim from the beast and slowly turn the muzzle of his rifle towards the spot where a moment earlier he had opened a loophole among the boughs, and fire, and the tiger immediately spring upon him and become merged with him, before my eyes, in a horrible writhing mass. Drowning the most deafening shouts that came from all the actors outside the cage as they ran instinctively towards the Nestoroff who had fallen at the shot, drowning the cries of Carlo Ferro, I heard there in the cage the deep growl of the beast and the horrible gasp of the man as he lay helpless in its fangs, in its claws, which were tearing his throat and chest; I heard, I heard, I kept on hearing above that growl, above that gasp, the continuous ticking of the machine, the handle of which my hand, alone, of its own accord, still kept on turning; and I waited for the beast to spring next upon me, having brought him down; and the moments of waiting seemed to me an eternity, and it seemed to me that throughout eternity I had been counting them, as I turned, still turned the handle, powerless to stop, when finally an arm was thrust in between the bars, carrying a revolver, and fired a shot point blank into the tiger’s ear over the mangled corpse of Nuti; and I was pulled back and dragged from the cage with the handle of the machine so tightly clasped in my fist that it was impossible at first to wrest it from me. I uttered no groan, no cry: my voice, from terror, had perished in my throat for ever.

Well, I have rendered the firm a service from which they will reap a fortune. As soon as I was able, I explained to the people who gathered round me terror-struck, first of all by signs, then in writing, that they were to take good care of the machine, which had been wrenched from my hand: that machine had in its maw the life of a man; I had given it that life to eat to the very last, until the moment when that arm had been thrust in to kill the tiger. There was a fortune to be extracted from this film, what with the enormous publicity and the morbid curiosity which the sordid atrocity of the drama of that slaughtered couple would everywhere arouse.

Ah, that it would fall to my lot to feed literally on the life of a man one of the many machines invented by man for his pastime, I could never have guessed. The life which this machine has devoured was naturally no more than it could be in a time like the present, in an age of machines; a production stupid in one aspect, mad in another, inevitably, and in the former more, in the latter rather less stamped with a brand of vulgarity.

I have found salvation, I alone, in my silence, with my silence, which has made me thus–according to the standard of the times–perfect. My friend Simone Pau will not understand this, more and more determined to drown himself in ‘superfluity’, the perpetual inmate of a Casual Shelter. I have already secured a life of ease with the compensation which the firm has given me for the service I have rendered it, and I shall soon be rich with the royalties which have been assigned to me from the hire of the monstrous film. It is true that I shall not know what to do with these riches; but I shall not reveal my embarrassment to anyone; least of all to Simone Pau, who comes every day to shake me, to abuse me, in the hope of forcing me out of this inanimate silence, which makes him furious. He would like to see me weep, would like me at least with my eyes to shew distress or anger; to make him understand by signs that I agree with him, that I too believe that life is there, in that ‘superfluity’ of his. I do not move an eyelid; I sit gazing at him, rigid, motionless, until he flies from the house in a rage. Poor Cavalena, from anoher angle, is studying on my behalf textbooks of nervous pathology, suggests injections and electric batteries, hovers round me to persuade me to agree to a surgical operation on my vocal chords; and Signorina Luisetta, penitent, heartbroken at my calamity, in which she chooses to detect an element of heroism, timidly lets me see now that she would like to hear issue, if not from my lips, at any rate from my heart a “yes” for herself.

No, thank you. Thanks to everybody. I have had enough. I prefer to remain like this. The times are what they are; life is what it is; and in the sense that I give to my profession, I intend to go on as I am–alone, mute and impassive–being the operator.

Is the stage set?

“Are you ready? Shoot….”

THE END

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (35)

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: -Shoot!, Archive O-P, Pirandello, Luigi, Pirandello, Luigi

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (27)

Shoot! (Si Gira, 1926). The Notebooks of Serafino Gubbio, Cinematograph Operator by Luigi Pirandello. Translated from the Italian by C. K. Scott Moncrieff

BOOK V

5

I have landed in a regular volcanic region. Eruptions and earthquakes without end. A big volcano, apparently snow-clad but inwardly in perpetual ebullition, Signora Nene. That one knew. But now there has come to light, unexpectedly, and has given its first eruption a little volcano, in whose bowels the fire has been lurking, hidden and threatening, albeit kindled but a few days ago.

The cataclysm was brought about by a visit from Polacco, this morning. Having come to persist in his task of persuading Nuti that he ought to leave Rome and return to Naples, to complete his convalescence, and after that should resume his travels, to distract his mind and be cured altogether, he had the painful surprise of finding Nuti up, as pale as death, with his moustache shaved clean to shew his firm intention of beginning at once, this very day, his career as an actor with the Kosmograph.

He shaved his moustache himself, as soon as he left his bed. It came as a surprise to all of us as well, because only last night the Doctor ordered him to keep absolutely quiet, to rest and not to leave his bed, except for an hour or so before noon; and last night he promised to obey these instructions.

We stood open-mouthed when we saw him appear shaved like that, completely altered, with that face of death, still not very steady on his legs, exquisitely attired.

He had cut himself slightly in shaving, at the left corner of his mouth; and the dried blood, blackening the cut, stood out against the chalky pallor of his face. His eyes, which now seemed enormous, with their lower lids stretched, as it were, by his loss of flesh, so as to shew the white of the eyeball beneath the line of the cornea, wore in confronting our pained stupefaction a terrible, almost a wicked expression of dark contempt and hatred.

“What in the world…” exclaimed Polacco.

He screwed up his face, almost baring his teeth, and raised his hands, with a nervous tremor in all his fingers; then, in the lowest of tones, indeed almost without speaking, he said:

“Leave me, leave me alone!”

“But you aren’t fit to stand!” Polacco shouted at him.

He turned and looked at him suspiciously:

“I can stand. Don’t worry me. I have… I have to go out… for a breath of air.”

“Perhaps it is a little soon, you know,” Cavalena tried to intervene, “if you will allow me….”

“But I tell you, I want to go out!” Nuti cut him short, barely tempering with a wry smile the irritation that was apparent in his voice.

This irritation springs from his desire to tear himself away from the attentions which we have been paying him recently, and which may have given us (though not me, I assure you) the illusion that he in a sense belongs to us from now onwards, is one of ourselves. He feels that this desire is held in check by his respect for the debt of gratitude which he owes to us, and sees no other way of breaking that bond of respect than by shewing indifference and contempt for his own health and welfare, so that we may begin to feel a resentment for the attentions we have paid him, and this resentment, at once creating a breach between him and ourselves, may absolve him from that debt of gratitude. A man in that state of mind dares not look people in the face And for that matter he, this morning, was not able to look any of us straight in the face.

Polacco, confronted by so definite a resolution, could see no other way out of the difficulty than to post round about him to watch, and, if need be, to defend him, as many of us as possible, and principally one who more than any of us has shewn pity for him and to whom he therefore owes a greater consideration; and, before going off with him, begged Cavalena emphatically to follow them at once to the Kosmograph, with Signorina Luisetta and myself. He said that Signorina Luisetta could not leave the film half-finished in which by accident she had been called upon to play a part, and that such a desertion would moreover be a real pity, because everyone was agreed that, in that short but by no means easy part, she had shewn a marvellous aptitude, which might lead, by his intervention, to a contract with the Kosmograph, an easy, safe and thoroughly respectable source of income, under her father’s protection.

Seeing Cavalena agree enthusiastically to this proposal, I was more than once on the point of going up to him to pluck him gently by the sleeve.

What I feared did, as a matter of fact, occur.

Signora Nene assumed that it was all a plot j engineered by her husband–Polacco’s morning call, Nuti’s sudden decision, the offer of a contract to her daughter–to enable him to go and flirt with the young actresses at the Kosmograph. And no sooner had Polacco left the house with Nuti than the volcano broke out in a tremendous eruption.

Cavalena at first tried to stand up to her, putting forward the anxiety for Nuti which obviously–as how in the world could anyone fail to see–had suggested this idea of a contract to Polacco. What? She didn’t care two pins about Nuti? Well, neither did he! Let Nuti go and hang himself a hundred times over, if once wasn’t enough! It was a question of seizing this golden opportunity of a contract for Luisetta! It would compromise her? How in the world could she be compromised, under the eyes of her father?

But presently, on Signora Nene’s part, argument ended, giving way to insults, vituperation, with such violence that finally Cavalena, indignant, exasperated, furious, rushed out of the house.

I ran after him down the stairs, along the street, doing everything in my power to stop him, repeating I don’t know how many times:

“But you are a Doctor! You are a Doctor!”

A Doctor, indeed! For the moment he was a wild beast in furious flight. And I had to let him escape, so that he should not go on shouting in the street.

He will come back when he is tired of running about, when once again the phantom of his tragicomic destiny, or rather of his conscience, appears before him, unrolling the dusty parchment certificate of his medical degree.

In the meantime, he will find a little breathing-space outside.

Returning to the house, I found, to my great and painful surprise, an eruption of the little volcano; an eruption so violent that the big volcano was almost overwhelmed by it.

She no longer seemed herself, Signorina Luisetta! All the disgust accumulated in all these years, from a childhood that had passed without ever a smile amid quarrels and scandal; all the disgraceful scenes which they had made her witness, she hurled in her mother’s face and at the back of her retreating father. Ah, so her mother was thinking now of her being compromised? When for all these years, with her idiotic, shameful insanity, she had destroyed her daughter’s existence, irreparably! Submerged in the sickening shame of a family which no one could approach without a feeling of revulsion! It was not compromising her, then, to keep her tied to that shame? Did her mother not hear how everyone laughed at her and at such a father? She had had enough, enough, enough! She had no wish to be tormented any longer by that laughter; she wished to free herself from the disgrace, and to make her escape by the way that was opening now before her, unsought, along which nothing worse could conceivably befall her! Away! Away! Away!

She turned to me, heated and trembling.

“You come with me, Signor Gubbio! I am going to my room to put on my hat, and then let us start at once!”

She ran off to her room. I turned to look at her mother.

Left speechless before her daughter who had at last risen to crush her with a condemnation which she at once felt to be all the more deserved inasmuch as she knew that the thought of her daughter’s being compromised was nothing more, really, than an excuse brought forward to prevent her husband from accompanying the girl to the Kosmograph; now, left face to face with me, with drooping head, her hands pressed to her bosom, she was endeavouring in a hoarse groan to liberate the cry of grief from her wrung, contracted bowels.

It pained me to see her.

All of a sudden, before her daughter returned, she raised her hands from her bosom and joined them in supplication, still powerless to speak, her whole face contracted in expectation of the tears which she had not yet succeeded in drawing up from their fount. In this attitude, she said to me with her hands what certainly she would never have said to me with her lips. Then she buried her face in them and turned away, as her daughter entered the room.

I drew the latter’s attention, pityingly, to her mother as she went off sobbing to her own room.

“Would you like me to go by myself?” Signorina Luisetta said menacingly.

“I should like you,” I answered sadly, “at least to calm yourself a little first.”

“I shall calm myself on the way,” she said, “Come along, let us be off.”

And a little later, when we had got into a carriage at the end of Via Veneto, she added:

“Anyhow, you’ll see, we are certain to find Papa at the Kosmograph.”

What made her add this reflexion? Was it to free me from the thought of the responsibility she was making me assume, in obliging me to accompany her? Then she is not really sure of her freedom to act as she chooses. In fact, she at once went on:

“Does it seem to you a possible life?”

“But if it is madness!” I reminded her. “If, as your father says, it is a typical form of paranoia?”

“Quite so, but for that very reason! Is it possible to go on living like that? When people have trouble of that sort, they can’t have a home any more; nor a family; nor anything. It is an endless struggle, and a desperate one, believe me! It can’t go on! What is to be done? What is to stop it? One flies off one way, another another. Everyone sees us, everyone knows. Our house stands open to the world. There is nothing left to keep secret! We might be living in the street. It is a disgrace! A disgrace!! Besides, you never know, perhaps this meeting violence with violence will make her shake off this madness which is driving us all mad! At least, I shall be doing something… I shall see things, I shall move about… I shall shake off this degradation, this desperation!”

“But if for all these years you have put up with this desperation, how in the world can you now, all of a sudden,” I found myself asking her, “rebel so fiercely?”

If, immediately after that little part which she had played in the Bosco Sacro, Polacco had suggested engaging her at the Kosmograph, would she not have recoiled from the suggestion, almost with horror? Why, of course! And yet the conditions at home were just the same then.

Whereas now here she is racing off with me to the Kosmograph! In desperation? Yes, but not on account of that mother of hers who gives her no peace.

How pale she turned, how ready she seemed to faint, as soon as her father, poor Cavalena, appeared with a face of terror in the doorway of the Kosmograph to inform us that “he,” Aldo Nuti, was not there, and that Polacco had telephoned to the management to say that he would not be coming there that day, so that there was nothing for it but to turn back.

“I can’t myself,” I said to Cavalena. “I have to remain here. I am very late as it is. You must take the Signorina home.”

“No, no, no, no!” shouted Cavalena. “I shall keep her with me all day; but afterwards I shall bring her back here, and you will oblige me, Signor Gubbio, by seeing her home, or she shall go alone. I, no; I decline to set foot in the house again! That will do, now! That will do!”

And off he went, accompanying his protests with an expressive gesture of his head and hands. Signorina Luisetta followed her father, shewing clearly in her eyes that she no longer saw any reason for what she had done. How cold the little hand was that she held out to me, and how absent her glance and hollow her voice, when she turned to take leave of me and to say to me:

“Till this evening.”

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (27)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: -Shoot!, Archive O-P, Pirandello, Luigi, Pirandello, Luigi

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (23)

Shoot! (Si Gira, 1926. The Notebooks of Serafino Gubbio, Cinematograph Operator by Luigi Pirandello. Translated from the Italian by C. K. Scott Moncrieff

BOOK V

1

I have just come from Aldo Nuti’s room. It is nearly one o’clock. The house–in which I am spending my first night–is asleep. It has for me a strange atmosphere, which I cannot as yet breathe with comfort; the appearance of things, the savour of life, special arrangements, traces of unfamiliar habits.

In the passage, as soon as I shut the door of Nuti’s room, holding a lighted match in my fingers, I saw close beside me, enormous on the opposite wall, my own shadow. Lost in the silence of the house, I felt my soul so small that my shadow there on the wall, grown so big, seemed to me the image of fear.

At the end of the passage, a door; outside this door, on the mat, a pair of shoes: Signorina Luisetta’s. I stopped for a moment to look at my monstrous shadow, which stretched out in the direction of this door, and the fancy came to me that the shoes were there to keep my shadow away. Suddenly, from inside the door, the old dog Piccini, who had already perhaps pricked her ears, on the alert from the first sound of a door being opened, uttered a couple of wheezy barks. It was not at the sound that she barked; but she had heard me stop in the passage for a moment; had felt my thoughts make their way into the bedroom of her young mistress, and so she barked.

Here I am in my new room. But it should not be this room. When I came here with my luggage, Cavalena, who was genuinely delighted to have me in the house, not only because of the warm affection and strong confidence which I at once inspired in him, but perhaps also because he hopes that it may be easier for him, by my influence, to find an opening in the Kosmograph, had allotted to me the other room, larger, more comfortable, better furnished.

Certainly neither he nor Signora Nene desired or ordered the change. It must be the work of Signorina Luisetta, who listened this morning in the carriage so attentively and with such dismay, as we drove away from the Kosmograph, to my summary account of Nuti’s misadventures. Yes, it must have been she, beyond question. My suspicion was confirmed a moment ago by the sight of her shoes outside the door, on the mat.

I am annoyed at the change for this reason only, that I myself, if this morning they had let me see both rooms, would have left the other to Nuti and have chosen this one for myself. Signorina Luisetta read my thoughts so clearly that without saying a word to me she has removed my things from the other room and arranged them in this. Certainly, if she had not done so, I should have been embarrassed at seeing Nuti lodged in this smaller and less comfortable of the rooms. But am I to suppose that she wished to spare me this embarrassment? I cannot. Her having done, without saying a word to me, what I would have done myself, offends me, albeit I realise that it is what had to be done, or rather precisely because I realise that it is what had to be done.

Ah, what a prodigious effect the sight of tears in a man’s eyes has on women, especially if they be tears of love. But I must be fair: they hare had a similar effect on myself.

He has kept me in there for about four hours. He wanted to go on talking and weeping: I stopped him, out of compassion chiefly for his eyes. I have never seen a pair of eyes brought to such a state by excessive weeping.

I express myself badly. Not by excessive weeping. Perhaps quite a few tears (he has shed an endless quantity), perhaps only a few tears would have been enough to bring his eyes to such a state.

And yet, it is strange! It appears that it is not he who is weeping. To judge by what he says, by what he proposes to do, he has no reason, nor, certainly, any desire to weep. The tears scald Ms eyes and cheeks, and therefore he knows that he is weeping; but he does not feel his own tears. His eyes are weeping almost for a grief that is not his, for a grief that is almost that of his tears themselves. His own grief is fierce, and refuses and scorns these tears.

But stranger still to my mind was this: that when at any point in his conversation his sentiments, so to speak, became lachrymose, his tears all at once began to slacken. While his voice grew tender and throbbed, his eyes, on the contrary, those eyes that a moment before were bloodshot and swollen with weeping, became dry and hard: fierce.

So that what he says and what his eyes say cannot correspond.

But it is there, in his eyes, and not in what he says that his heart lies. And therefore it was for his eyes chiefly that I felt compassion. Let him not talk and weep; let him weep and listen to his own weeping: it is the best thing that he can do.

There comes to me, through the wall, the sound of his step. I have advised him to go to bed, to try to sleep. He says that he cannot; that he has lost the power to sleep, for some time past. What has made him lose it? Not remorse, certainly, to judge by what he says.

Among all the phenomena of human nature one of the commonest, and at the same time one of the strangest when we study it closely, is this of the desperate, frenzied struggle which every man, however ruined by his own misdeeds, conquered and crushed in his affliction, persists in keeping up with his own conscience, in order not to acknowledge those misdeeds and not to make them a matter for remorse. That others acknowledge them and punish him for them, imprison him, inflict the cruellest tortures upon him and kill him, matters not to him; so long as he himself does not acknowledge them, but withstands his own conscience which cries them aloud at him.

Who is he? Ah, if each one of us could for an instant tear himself away from that metaphorical ideal which our countless fictions, conscious and unconscious, our fictitious interpretations of our actions and feelings lead us inevitably to form of ourselves; he would at once perceive that this ‘he’is ‘another’, another who has nothing or but very little in common with himself; and that the true ‘he’ is the one that is crying his misdeeds aloud within him; the intimate being, often doomed for the whole of our lives to remain unknown to us! We seek at all costs to preserve, to maintain in position that metaphor of ourselves, our pride and our love. And for this metaphor we undergo martyrdom and ruin ourselves, when it would be so pleasant to let ourselves succumb vanquished, to give ourselves up to our own inmost being, which is a dread deity, if we oppose ourselves to it; but becomes at once compassionate towards our every fault, as soon as we confess it, and prodigal of unexpected tendernesses. But this seems a negation of self, something unworthy of a man; and will ever be so, so long as we believe that our humanity consists in this metaphor of ourselves.

The version given by Aldo Nuti of the mishaps that have brought him low–it seems impossible!–aims above all at preserving this metaphor, his masculine vanity, which, albeit reduced before my eyes to this miserable plight, refuses nevertheless to humble itself to the confession that it has been a silly toy in the hands of a woman: a toy, a doll filled with sawdust, which the Nestoroff, after amusing herself for a while by making it open its arms and close them in an attitude of prayer, pressing with her finger the too obvious spring in its chest, flings away into a corner, breaking it in its fall.

It has risen to its feet again, this broken doll; its porcelain face and hands in a pitiful state: the hands without fingers, the face without a nose, all cracked and chipped; the spring in its chest has made a rent in the red woollen jacket and dangles out, broken; and yet, no, what is this: the doll cries out no, that it is not true that that woman made it open its arms and close them in an attitude of prayer to laugh at it, nor that, after laughing at it, she has broken it like this. It is not true!

By agreement with Duccella, by agreement with Granny Rosa he followed the affianced lovers from the villa by Sorrento to Naples, to save poor Giorgio, too innocent, and blinded by the fascination of that woman. It did not require much to save him! Enough to prove to him, to let him assure himself by experiment that the woman whom he wished to make his by marrying her, could be his, as she had been other men’s, as she would be any man’s, without any necessity of marrying her. And thereupon, challenged by poor Giorgio, he set to work to make the experiment at once. Poor Giorgio believed it to be impossible because, as might be expected, with the tactics common among women of her sort, the Nestoroff had always refused to grant him even the slightest favour, and at Capri he had seen her so contemptuous of everyone, so withdrawn and aloof! It was a horrible act of treachery. Not his action, though, but Giorgio Mirelli’s! He had promised that on receiving the proof he would at once leave the woman: instead, he killed himself.

This is the version that Aldo Nuti chooses to give of the drama.

But how, then? Was it he, the doll, that was playing the trick? And how comes he to be broken like this? If it was so easy a trick? Away with these questions, and away with all surprise. Here one must make a show of believing. Our pity must not diminish but rather increase at the overpowering necessity to lie in this poor doll, which is Aldo Nuti’s vanity: the face without a nose, the hands without fingers, the spring in the chest broken, dangling out through the rent jacket, we must allow him to lie! Only, his lies give him an excuse for weeping all the more.

They are not good tears, because he does not wish to feel his own grief in them. He does not wish them, and he despises them. He wishes to do something other than weep, and we shall have to keep him under observation. Why has he come here? He has no need to be avenged on anyone, if the treachery lay in Giorgio Mirelli’s action in killing himself and flinging his dead body between his sister and her lover. So much I said to him.

“I know,” was his answer. “But there is still she, that woman, the cause of it all! If she had not come to disturb Giorgio’s youth, to bait her hook, to spread her net for him with arts which really can be treacherous only to a novice, not because they are not treacherous in themselves, but because a man like myself, like you, recognises them at once for what they are: vipers, which we render harmless by extracting the teeth which we know to be venomous; now I should not be caught like that: I should not be caught like that! She at once saw in me an enemy, do you understand? And she tried to sting me by, stealth. From the very beginning I, on purpose, allowed her to think that it would be the easiest thing in the world for her to sting me. I wished her to shew her teeth, just so that I might draw them. And I was successful. But Giorgio, Giorgio, Giorgio had been poisoned for ever! He should have let me know that it was useless my attempting to draw the teeth of that viper….”

“Not a viper, surely!” I could not help observing. “Too much innocence for a viper, surely! To offer you her teeth so quickly, so easily…. Unless she did it to cause the death of Giorgio Mirelli.”

“Perhaps.”

“And why? If she had already succeeded in her plan of making him marry her? And did she not yield at once to your trick? Did she not let you draw her teeth before she had attained her object?”

“But she had no suspicion!”

“In that case, how in the world is she a viper? Would you have a viper not suspect? A viper would have stung after, not before! If she stung first, it means that… either she is not a viper, or for Giorgio’s sake she was willing to lose her teeth. Excuse me… no, wait a minute… please stop and listen to me… I tell you this because… I am quite of your opinion, you know… she did wish to be avenged, but at first, only at the beginning, upon Giorgio. This is my belief; I have always thought so.”

“Be avenged for what?”

“Perhaps for an insult which no woman will readily allow.”

“Woman, you say! She!”

“Yes, indeed, a woman, Signor Nuti! You who know her well, know that they are all the same, especially on this point.”

“What insult? I don’t follow you.”

“Listen: Giorgio was entirely taken up with his art, wasn’t he?”

“Yes.”

“He found at Capri this woman, who offered herself as an object of contemplation to him, to his art.”

“Precisely, yes.”

“And he did not see, he did not wish to see in her anything but her body, but only to caress it upon a canvas with his brushes, with the play of lights and colours. And then she, offended and piqued, to avenge herself, seduced him (there I agree with you!); and, having seduced him, to avenge herself further, to avenge herself still better, resisted him (am I right?) until Giorgio, blinded, in order to secure her, proposed marriage, took her to Sorrento to meet his grandmother, his sister.”

“No! It was her wish! She insisted upon it!”

“Very well, then; it was she; and I might say, insult for insult; but no, I propose now to abide by what you have said, Signor Nuti! And what you have said makes me think, that she may have insisted upon Giorgio’s taking her there, and introducing her to his grandmother and sister, expecting that Giorgio would revolt against this imposition, so that she might find an excuse for releasing herself from the obligation to marry him.”

“Release herself? Why?”

“Why, because she had already attained her object! Her vengeance was complete: Giorgio, crushed, blinded, captivated by her, by her body, to the extent of wishing to marry her! This was enough for her, and she asked for nothing more! All the rest, their wedding, life with him who would be certain to repent immediately of their marriage, would have meant unhappiness for her and for him, a chain. And perhaps she was not thinking only of herself; she may have felt some pity also for him!”

“Then you believe?”

“But you make me believe it, you make me think it, by maintaining that the woman is treacherous! To go by what you say, Signor Nuti, in a treacherous woman what she did is not consistent. A treacherous woman who desires marriage, and before her marriage gives herself to you so easily…”

“Gives herself to me?” came with a shout of rage from Aldo Nuti, driven by my arguments with his back to the wall. “Who told you that she gave herself to me? I never had her, I never had her…. Do you imagine that I can ever have thought of having her? All I required was the proof which she would not have failed to provide… a proof to shew to Giorgio!”

I was left speechless for a moment, gazing at him.

“And that viper let you have it at once? And you were able to secure it without difficulty, this proof! But then, but then, surely…”

I supposed that at last my logic had the victory so firmly in its grasp that it would no longer be possible to wrest it from me. I had yet to learn, that at the very moment when logic, striving against passion, thinks that it has secured the victory, passion with a sudden lunge snatches it back, and then with buffetings and kicks sends logic flying with all its escort of linked conclusions.

If this unfortunate man, quite obviously the dupe of this woman, for a purpose which I believe myself to have guessed, could not make her his, and has been left accordingly with this rage still in his body, after all that he has had to suffer, because that silly doll of his vanity believed honestly perhaps at first that it could easily play with a woman like the Nestoroff; what more can one say? Is it possible to induce him to go away? To force him to see that he can have no object in provoking another man, in approaching a woman who does not wish to have anything more to do with him?

Well, I have tried to induce him to go away, and have asked him what, in short, he wanted, and what he hoped from this woman.

“I don’t know, I don’t know,” he cried. “She ought to stay with me, to suffer with me. I can’t do without her any longer, I can’t be left alone any more like this. I have tried up to now, I have done everything to win Duccella over; I have made ever so many of my friends intercede for me; but I realise that it is not possible. They do not believe in my agony, in my desperation. And now I feel a need, I must cling on to some one, not be alone like this any more. You understand: I am going mad, I am going mad! I know that the woman herself is utterly worthless; but she acquires a value now from everything that I have suffered and am suffering through her. It is not love, it is hatred, it is the blood that has been shed for her! And since she has chosen to submerge my life for ever in that blood, it is necessary now that we plunge into it both together, clinging to one another, she and I, not I alone, not I alone! I cannot be left alone like this any more!”

I came away from his room without even the satisfaction of having offered him an outlet which might have relieved his heart a little. And now I can open the window and lean out to gaze at the sky, while he in the other room wrings his hands and weeps, devoured by rage and grief. If I went back now, into his room, and said to him joyfully; “I say, Signor Nuti, there are still the stars! You of course have forgotten them, but they are still there!” what would happen? To how many men, caught in the throes of a passion, or bowed down, crushed by sorrow, by hardship, would it do good to think that there, above the roof, is the sky, and that in the sky there are the stars. Even if the fact of the stars’ being there did not inspire in them any religious consolation. As we gaze at them, our own feeble pettiness is engulfed, vanishes in the emptiness of space, and every reason for our torment must seem to us meagre and vain. But we must have in ourselves, in the moment of passion, the capacity to think of the stars. This may be found in a man like myself, who for some time past has looked at everything, himself included, from a distance. If I were to go in there and tell Signor Nuti that the stars were shining in the sky, he would perhaps shout back at me to give them his kind regards, and would turn me out of the room like a dog.

But can I now, as Polacco would like, constitute myself his guardian? I can imagine how Carlo Ferro will glare at me presently, on seeing me come to the Kosmograph with him by my side. And God knows that I have no more reason to be a friend of one than of the other.

All I ask is to continue, with my usual impassivity, my work as an operator. I shall not look out of the window. Alas, since that cursed Senator Zeme has been to the Kosmograph, I see even in the sky a ‘marvel’ of cinematography.

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (23)

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: -Shoot!, Archive O-P, Pirandello, Luigi, Pirandello, Luigi

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (19)

Shoot! (Si Gira, 1926) The Notebooks of Serafino Gubbio, Cinematograph Operator by Luigi Pirandello. Translated from the Italian by C. K. Scott Moncrieff

BOOK IV

2

We were waiting to-day, beneath the pergola of the tavern, for the arrival of a certain “young lady of good family,” recommended by Bertini, who was to take a small part in a film which has been left for some months unfinished and which they now wish to complete.

More than an hour had passed since a boy had been sent on a bicycle to this young lady’s house, and still there was no sign of anyone, not even of the boy returning.

Polacco was sitting with me at one table, the Nestoroff and Carlo Ferro were at another. All four of us, with the young lady we were expecting, were to go in a motor-car for a “nature scene” in the Bosco Sacro.

The sultry afternoon heat, the nuisance of the myriad flies of the tavern, the enforced silence among us four, obliged to remain together notwithstanding the openly declared and for that matter obvious aversion felt by the other two for Polacco and also for myself, increased the strain of waiting until it became quite intolerable.

The Nestoroff was obstinately restraining herself from turning her eyes in our direction. But she was certainly aware that I was looking at her, covertly, while apparently paying her no attention; and more than once she had shewn signs of annoyance. Carlo Ferro had noticed this and had knitted his brows, keeping a close watch on her; and then she had pretended for his benefit to be annoyed, not indeed by myself who was looking at her, but by the sun which, through the vine leaves of the pergola, was beating upon her face. It was true; and a wonderful sight was the play, on that face, of the purple shadows, straying and shot with threads of golden sunlight, which lighted up now one of her nostrils, and part of her upper lip, now the lobe of her ear and a patch of her throat.

I find myself assailed, at times, with such violence by the external aspects of things that the clear, outstanding sharpness of my perceptions almost terrifies me. It becomes so much a part of myself, what I see with so sharp a perception, that I am powerless to conceive how in the world a given object–thing or person–can be other than what I would have it be. The Nestoroff’s aversion, in that moment of such intensely lucid perception, was intolerable to me. How in the world did she not understand that I was not her enemy?

Suddenly, after peering out for a little through the trellis, she rose, and we saw her stroll out, towards a hired carriage, which also had been standing there for an hour outside the entrance to the Kosmograph, waiting under the blazing sun. I too had noticed the carriage; but the foliage of the vine prevented me from seeing who was waiting in it. It had been waiting there for so long that I could not believe that there was anybody in it. Polacco rose; I rose also, and we looked out.

A young girl, dressed in a sky-blue frock, of Swiss material, very light, with a straw hat, trimmed with black velvet ribbons, sat waiting in the carriage. Holding in her lap an aged dog with a shaggy coat, black and white, she was timidly and anxiously watching the taximeter of the carriage, which every now and then gave a click, and must already be indicating a considerable sum. The Nestoroff went up to her with great civility and invited her to come inside, to escape from the rays of the sun. Would it not be better to wait beneath the pergola of the tavern?

“Plenty of flies, of course. But at any rate one can sit in the shade.”

The shaggy dog had begun to growl at the Nestoroff, baring its teeth in defence of its young mistress. She, turning suddenly crimson, perhaps at the unexpected pleasure of seeing this beautiful lady shew an interest in her with such courtesy; perhaps also from the annoyance that her stupid old pet was causing her, which received the other’s cordial invitation in so unfriendly a spirit, thanked her, accepted the invitation with some confusion, and stepped down from the carriage with the dog under her arm. I had the impression that she left the carriage chiefly to make amends for the old dog’s hostile reception of the lady. And indeed she slapped it hard on the muzzle with her hand, calling out:

“Be quiet, Piccini!”

And then, turning to the Nestoroff:

“I apologise for her, she doesn’t understand. . . . “

And they came in together beneath the pergola. I studied the old dog which was angrily looking its young mistress up and down, with the eyes of a human being. It seemed to be saying to her: “And what do ‘you’ understand?”

Polacco, in the mean time, had advanced towards her and was asking politely:

“Signorina Luisetta?”

She turned a deep crimson, as though lost in a painful surprise, at being recognised by some one whom she did not know; smiled; nodded her head in the affirmative, and all the black ribbons on her straw hatnodded with her.

Polacco went on to ask her:

“Is Papa here?”

Yes, once more, with her head, as though amid her blushes and confusion she could not find words with which to answer. At length, with an effort, she found a timid utterance:

“He went inside some time ago: he said that he would have finished his business at once, and now . . . “

She raised her eyes to look at the Nestoroff and smiled at her, as though she were sorry that this gentleman with his questions had distracted her attention from the lady, who had been so kind to her without even knowing who she was. Polacco thereupon introduced them:

“Signorina Luisetta Cavalena; Signora Nestoroff.”

He then turned and beckoned to Carlo Ferro, who at once sprang to his feet and bowed awkwardly.

“Carlo Ferro, the actor.”

Last of all, he introduced me:

“Gubbio.”

It seemed to me that, among the lot of us, I was the one who frightened her least.

I knew by repute Cavalena, her father, notorious at the Kosmograph by the nickname of ‘Suicide’. It seems that the poor man is terribly oppressed by a jealous wife. Owing to his wife’s jealousy he has been obliged to renounce first of all a commission in the Militia, as Surgeon Lieutenant, and one good practice after another; then, his independent work, as well, and journalism, in which he had found an opening, and finally teaching also, to which he had turned in desperation, in the technical schools, as a lecturer on physics and natural history. Now, not being able (still on account of his wife) to devote himself to the drama, for which he has for some time past believed himself to have a distinct talent, he has turned to the composition of scenarios for the cinematograph, with great loathing, ‘obtorto collo’, in order to supply the wants of his family, since they are unable to live exclusively upon his wife’s fortune, and what little they make by letting a pair of furnished rooms. Unfortunately, in the hell of his home life, having now grown accustomed to viewing the world as a prison, it seems that, however hard he may try, he can never succeed in composing a plot for a film without dragging in,

somewhere or other, a suicide. Which accounts for Polacco’s having steadily, up to the present, rejected all his scenarios, in view of the fact that the English decline, absolutely, to hear of a suicide in their films.

“Has he come to see me?” Polacco asked Signorina Luisetta.

Signorina Luisetta stammered in confusion:

“No,” she said… “I don’t think so; Bertini, I think it was.”

“Ah, the rascal! He has gone to Bertini, has he? But tell me, Signorina, did he go in alone?”

Fresh, and still more vivid blushes on the part of Signorina Luisetta.

“With Mamma.”

Polacco threw up his hands and waved them in the air, pulling a long face and winking.

“Let us hope that nothing dreadful is going to happen!”

Signorina Luisetta made an effort to smile; and echoed:

“Let us hope so . . . “

And it hurt me so to see her smile like that, with her little face aflame! I would have liked to shout at Polacco:

“Stop tormenting her with these questions! Can’t you see that you are making her utterly miserable?”

But Polacco, all of a sudden, had an idea; he clapped his hands:

“Why shouldn’t we take Signorina Luisetta? By Jove, yes; we have been waiting here for the last hour! Why yes, of course. My dear young lady, you will be helping us out of a difficulty, and you will see that we shall give you plenty of fun. It will all be over in half an hour. I shall tell the porter, as soon as your father and mother come out, to let them know that you have gone for half an hour with me and this lady and gentleman. I am such a friend of your father that I can venture to take the liberty. I shall give you a little part to play, you will like that?”

Signorina Luisetta had evidently a great fear of appearing timid, embarrassed, foolish; and, as for coming with us, said: “Why not?” But, when it came to acting, she could not, she did not know how . . . and in those clothes, too–really? . . . she had never tried . . . she felt ashamed . . . besides . . .

Polacco explained to her that nothing serious was required: she would not have to open her mouth, nor to mount a stage, nor to appear before the public. Nothing at all. It would be in the country. Among the trees. “Without a word spoken.

“You will be sitting on a bench, beside this gentleman,” he pointed to Ferro. “This gentleman will pretend to be making love to you. You, naturally, do not believe him, and laugh at him. … Like that…. Splendid! You laugh and shake your head, plucking the petals off a flower. All of a sudden, a motor-car dashes up. This gentleman starts to his feet, frowns, looks round him, scenting danger in the air. You stop plucking at the flower and adopt an attitude of doubt, dismay. Suddenly this lady,” here he pointed to the Nestoroff, “jumps down from the car, takes a revolver from her muff and fires at you . . . “

Signorina Luisetta opened her eyes wide and stared at the Nestoroff, in terror.

“In make-believe! Don’t be frightened!” Polacco went on with a smile. “The gentleman runs forward, disarms the lady; meanwhile you have sunk down, first of all, on the bench, mortally wounded; from the bench you fall to the ground–without hurting yourself, please! and it is all over…. Come, come, don’t let us waste any more time! We can rehearse the scene on the spot; you will see, it will go off splendidly … and what a fine present you will get afterwards from the Kosmograph!”

“But if Papa . . . “

“We shall leave a message for him!”

“And Piccini?”

“We can take her with us; I shall carry her myself…. You will see, the Kosmograph will give Piccini a fine present too . . . . Come along, let us be off!”

As we got into the motor-car (again, I am certain, so as not to appear timid and foolish), she, who had not given me a second thought, looked at me doubtfully.

Why was I coming too! What part was I to play?

No one had uttered a word to me; I had been barely introduced, named as a dog might be; I had not opened my mouth; I remained silent . . . .

I noticed that my silent presence, the necessity for which she failed to see, but which impressed her, nevertheless, as being mysteriously necessary, was beginning to disturb her. No one thought of offering her any explanation; I could not offer her one myself. I had seemed to her ‘a person like the rest’; or rather, at first sight, a person ‘more akin to herself’ than the rest. Now she was beginning to be aware that for these other people and also for herself (in a vague way) I was not, properly speaking, a person. She began to feel that my person was not necessary; but that my presence there had the necessity of a ‘thing’, which she as yet did not understand; and that I remained silent for that reason. They might speak, yes, they, all four of them–because they were people, each of them represented a person, his or her own; but I, no: I was a thing: why, perhaps the thing that was resting on my knees, wrapped in a black cloth.

And yet I too had a mouth to speak with, eyes to see with, and the said eyes, look, were shining as they rested on her; and certainly within myself I felt . . .

Oh, Signorina Luisetta, if you only knew the joy that his own feelings were affording the person– ‘not necessary’ as such, but as a thing–who sat opposite to you! Did it occur to you that I–albeit seated in front of you like that, like a thing–was capable of feeling within myself? Perhaps. But what I was feeling, behind my mask of impassivity, that you certainly could not imagine.

Feelings that were ‘not necessary’, Signorina Luisetta! You do not know what they are, nor do you know the intoxicating joy that they can give! This machine here, for instance: does it seem to you that there can be any necessity for it to feel? There cannot be! If it could feel, what feelings would it have? Not necessary feelings, surely.

Something that was a luxury for it. Fantastic things . . . .

Well, among the four of you, to-day, I–a pair of legs, a lap, and on it a machine–I felt ‘fantastically’.

You, Signorina Luisetta, were, with everything round about you, contained in my feelings, which rejoiced in your innocence, in the pleasure that you derived from the breeze in your face, the view of the open country, the proximity of the beautiful lady. Does it seem strange to you that you entered like that, with everything round about you, into my feelings? But may not a beggar by the roadside perhaps see the road and all the people who go past, comprised in that feeling of pity which he seeks to arouse? You, being more sensitive than the rest, as you pass, notice that you enter into his feeling, and stop and give him the charity of a copper. Many others do not enter in, and it does not occur to the beggar that they are outside his feeling, inside another of their own, in which he too is included as a shadowy nuisance; the beggar thinks that they are hard-hearted. What was I to you in your feelings, Signorina Luisetta î A mysterious man? Yes, you are quite right. Mysterious. If you knew how I feel, at certain moments, my ‘inanimate silence’! And I revel in the mystery that is exhaled by this silence for such as are capable of remarking it. I should like never to speak at all; to receive everyone and everything in this silence of mine, every tear, every smile; not to provide, myself, an echo to the smile; I could not; not to wipe away, myself, the tear; I should not know how; but so that all might find in me, not only for their griefs, but also and even more for their joys, a tender pity that would make us brothers if only for a moment.

I am so grateful for the good that you have done with the freshness of your timid, smiling innocence, to the lady who was sitting by your side! So at times, when the rain does not come, parched plants find refreshment in a breath of air. And this breath of air you yourself were, for a moment, in the burning desert of the feelings of that woman who sat beside you; a burning desert that does not know the refreshing coolness of tears.

At one point she, looking at you almost with a frightened admiration, took your hand in her own and stroked it. Who knows what bitter envy of you was torturing her heart at that moment?

Did you see how, immediately afterwards, her face darkened?

A cloud had passed . . . . What cloud?

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (19)

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: -Shoot!, Pirandello, Luigi

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (11)

Shoot! (Si Gira, 1926). The Notebooks of Serafino Gubbio, Cinematograph Operator by Luigi Pirandello. Translated from the Italian by C. K. Scott Moncrieff

BOOK II

5

A problem which I find it far more difficult to solve is this: how in the world Giorgio Mirelli, who would fly with such impatience from every complication, can have lost himself to this woman, to the point of laying down his life on her account.

Almost all the details are lacking that would enable me to solve this problem, and I have said already that I have no more than a summary report of the drama.

I know from various sources that the Nestoroff, at Capri, when Giorgio Mirelli saw her for the first time, was in distinctly bad odour, and was treated with great diffidence by the little Russian colony, which for some years past has been settled upon that island.

Some even suspected her of being a spy, perhaps because she, not very prudently, had introduced herself as the widow of an old conspirator, who had died some years before her coming to Capri, a refugee in Berlin. It appears that some one wrote for information, both to Berlin and to Petersburg, with regard to her and to this unknown conspirator, and that it came to light that a certain Nikolai Nestoroff had indeed been for some years in exile in Berlin, and had died there, but without ever having given anyone to understand that he was exiled for political reasons. It appears to have become known also that this Nikolai Nestoroff had taken her, as a little girl, from the streets, in one of the poorest and most disreputable quarters of Petersburg, and, after having her educated, had married her; and then, reduced by his vices to the verge of starvation had lived upon her, sending her out to sing in music-halls of the lowest order, until, with the police on his track, he had made his escape, alone, into Germany. But the Nestoroff, to my knowledge, indignantly denies all these stories.

That she may have complained privately to some one of the ill-treatment, not to say the cruelty she received from her girlhood at the hands of this old man is quite possible; but she does not say that he lived upon her; she says rather that, of her own accord, obeying the call of her passion, and also, perhaps, to supply the necessities of life, having overcome his opposition, she took to acting in the provinces, a-c-t-i-n-g, mind, on the legitimate stage; and that then, her husband having fled from Russia for political reasons and settled in Berlin, she, knowing him to be in frail health and in need of attention, taking pity on him, had joined him there and remained with him till his death. What she did then, in Berlin, as a widow, and afterwards in Paris and Vienna, cities to which she often refers, shewing a thorough knowledge of their life and customs, she neither says herself nor certainly does anyone ever venture to ask her.

For certain people, for innumerable people, I should say, who are incapable of seeing anything but themselves, love of humanity often, if not always, means nothing more than being pleased with themselves.

Thoroughly pleased with himself, with his art, with his studies of landscape, must Giorgio Mirelli, unquestionably, have been in those days at Capri.

Indeed–and I seem to have said this before–his habitual state of mind was one of rapture and amazement. Given such a state of mind, it is easy to imagine that this woman did not appear to him as she really was, with the needs that she felt, wounded, scourged, poisoned by the distrust and evil gossip that surrounded her; but in the fantastic transfiguration that he at once made of her, and illuminated by the light in which he beheld her. For him feelings must take the form of colours, and, perhaps, entirely engrossed in his art, he had no other feeling left save for colour. All the impressions that he formed of her were derived exclusively, perhaps, from the light which he shed upon her; impressions, therefore, that were felt by him alone. She need not, perhaps could not participate in them. Now, nothing irritates us more than to be shut out from an enjoyment, vividly present before our eyes, round about us, the reason of which we can neither discover nor guess. But even if Giorgio Mirelli had told her of his enjoyment, he could not have conveyed it to her mind. It was a joy felt by him alone, and proved that he too, in his heart, prayed and wished for nothing else of her than her body; not, it is true, like other men, with base intent; but even this, in the long run–if you think it over carefully–could not but increase the woman’s irritation. Because, if the failure to derive any assistance, in the maddening uncertainties of her spirit, from the many who saw and desired nothing in her save her body, to satisfy on it the brutal appetite of the senses, filled her with anger and disgust; her anger with the one man, who also desired her body and nothing more; her body, but only to extract from it an ideal and absolutely self-sufficient pleasure, must have been all the stronger, in so far as every provocative of disgust was entirely lacking, and must have rendered more difficult, if not absolutely futile, the vengeance which she was in the habit of wreaking upon other people. An angel, to a woman, is always more irritating than a beast.

I know from all Giorgio Mirelli’s artist friends in Naples that he was spotlessly chaste, not because he did not know how to make an impression upon women, but because he instinctively avoided every vulgar distraction.

To account for his suicide, which beyond question was largely due to the Nestoroff, we ought to assume that she, not cared for, not helped, and irritated to madness, in order to be avenged, must with the finest and subtlest art have contrived that her body should gradually come to life before his eyes, not for the delight of his eyes alone; and that, when she saw him, like all the rest, conquered and enslaved, she forbade him, the better to taste her revenge, to take any other pleasure from her than that with which, until then, he had been content, as the only one desired, because the only one worthy of him.

‘We ought’, I say, to assume this, but only if we wish to be ill-natured. The Nestoroff might say, and perhaps does say, that she did nothing to alter that relation of pure friendship which had grown up between herself and Mirelli; so much so that when he, no longer contented with that pure friendship, more impetuous than ever owing to the severe repulse with which she met his advances, yet, to obtain his purpose, offered to marry her, she struggled for a long time–and this is true; I learned it on good authority–to dissuade him, and proposed to leave Capri, to disappear; and in the end remained there only because of his acute despair.

But it is true that, if we wish to be ill-natured, we may also be of opinion that both the early repulse and the later struggle and threat and attempt to leave the island, to disappear, were perhaps so many artifices carefully planned and put into practice to reduce this young man to despair after having seduced him, and to obtain from him all sorts of things which otherwise he would never, perhaps, have conceded to her. Foremost among them, that she should be introduced as his future bride at the Villa by Sorrento to that dear Granny, to that sweet little sister, of whom he had spoken to her, and to the sister’s betrothed.

It seems that he, Aldo Nuti, more than, the two women, resolutely opposed this claim. Authority and power to oppose and to prevent this marriage he did not possess, for Giorgio was now his own master, free to act as he chose, and considered that he need no longer give an account of himself to anyone; but that he should bring this woman to the house and place her in contact with his sister, and expect the latter to welcome her and to treat her as a sister, this, by Jove, he could and must oppose, and oppose it he did with all his strength. But were they, Granny Rosa and Duccella, aware what sort of woman this was that Giorgio proposed to bring to the house and to marry? A Russian adventuress, an actress, if not something worse! How could he allow such a thing, how not oppose it with all his strength?

Again “with all his strength”… Ah, yes, who knows how hard Granny Rosa and Duccella had to fight in order to overcome, little by little, by their sweet and gentle persuasion, all the strength of Aldo Nuti. How could they have imagined what was to become of that strength at the sight of Varia Nestoroff, as soon as she set foot, timid, ethereal and smiling, in the dear villa by Sorrento!

Perhaps Giorgio, to account for the delay which Granny Rosa and Duccella shewed in answering, may have said to the Nestoroff that this delay was due to the opposition “with all his strength” of his sister’s future husband; so that the Nestoroff felt the temptation to measure her own strength against this other, at once, as soon as she set foot in the villa. I know nothing! I know that Aldo Nuti was drawn in as though into a whirlpool and at once carried away like a wisp of straw by passion for this woman.

I do not know him. I saw him as a boy, once only, when I was acting as Giorgio’s tutor, and he struck me as a fool. This impression of mine does not agree with what Mirelli said to me about him, on my return from Liege, namely that he was ‘complicated’. Nor does what I have heard from other people, with regard to him correspond in the least with this first impression, which however has irresistibly led me to speak of him according to the idea that I had formed of him from it. I must, really, have been mistaken. Duccella found it possible to love him! And this, to my mind, does more than anything else to prove me in the wrong. But we cannot control our impressions. He may be, as people tell me, a serious young man, albeit of a most ardent temperament; for me, until I see him again, he will remain that fool of a boy, with the baron’s coronet on his handkerchiefs and portfolios, the young gentleman who ‘would so love to become an actor’.

He became one, and not by way of make-believe, with the Nestoroff, at Giorgio Mirelli’s expense. The drama was unfolded at Naples, shortly after the Nestoroff’s introduction and brief visit to the house at Sorrento. It seems that Nuti returned to Naples with the engaged couple, after that brief visit, to help the inexperienced Giorgio and her who was not yet familiar with the town, to set their house in order before the wedding.

Perhaps the drama would not have happened, or would have had a different ending, had it not been for the complication of Duccella’s engagement to, or rather her love for Nuti. For this reason Giorgio Mirelli was obliged to concentrate on himself the violence of the unendurable horror that overcame him at the sudden discovery of his betrayal.

Aldo Nuti rushed from Naples like a madman before there arrived from Sorrento at the news of Giorgio’s suicide Granny Rosa and Duccella.

Poor Duccella, poor Granny Rosa! The woman who from thousands and thousands of miles away came to bring confusion and death into your little house where with the jasmines bloomed the most innocent of idylls, I have her here, now, in front of my machine, every day; and, if the news I have heard from Polacco be true, I shall presently have him here as well, Aldo Nuti, who appears to have heard that the Nestoroff is leading lady with the Kosmograph.

I do not know why, my heart tells me that, as I turn the handle of this photographic machine, I am destined to carry out both your revenge and your poor Giorgio’s, dear Duccella, dear Granny Rosa!

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (11)

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

(to be continued)

More in: -Shoot!, Archive O-P, Pirandello, Luigi, Pirandello, Luigi

L u i g i P i r a n d e l l o

(1867-1936)

Tormenti

Quando in croce Gesú l’anima rese,

tutta, per un momento,

su la terra la vita si sospese,

sospese anche l’inferno ogni tormento.

Sisifo che per l’erta maledetta

avea sospinto il masso

fin su l’aspra del colle aguzza vetta,

donde tuttor riprecipita al basso,

fermo, lassú, starsi d’un tratto il vede:

stupefatto, in un oh!

fermo, di sasso, anch’egli resta, e fede

al prodigio prestar non sa, non può.

Si guarda attorno, una e due volte scuote

il macigno che sta;

vi siede e, con le pugna su le gote,

poi domanda a se stesso: – «E or che si fa?» –

Ma sotto, ecco, gli ruzzola il fatale

sasso di nuovo; ratto

balza egli in pie’, lo segue, e: – «Manco male! –

dice. – Almeno cosí, via, m’arrabatto». –

E, mentre sú per l’erta novamente

contro il masso si slancia,

tra le doglie piú là, Tantalo sente

gridare urlare: – «Ahi Dio! Ahi Dio! la pancia!» –

Aggirandosi come una bufera,

satollo, il poveretto,

in quella tregua momentanea s’era

di tutto quanto il suo crudel banchetto.

Ed or gemeva: – «Non lo farò piú!

Beato chi desia

e nulla ottiene mai! Grazia, Gesú!

Sia benedetta la condanna mia!» –

Leggendo la Storia

Sú, allegra, allegra, cara mia! Mi pare

che tu la prenda un po’ troppo sul serio.

Delitti, infamie, sí, senza criterio,

impudicizie da strasecolare;

ma gajo papa era Alessandro Borgia,

tranquillo e ingenuo nelle sue nequizie;

tranne quel della donna, senza vizi, e

sobrio, anzi frugale in mezzo all’orgia.

Ebbe per l’oro, è vero, anima lurca,

ma lo spendeva poi, tutto, tal quale.

Né per un papa infin la vedo male

che andasse a caccia vestito alla turca.

Di piú d’un figlio con Vannozza reo,

diede a Vannozza sua piú d’un marito;

ma l’ultimo, il Canal, bravo erudito:

il Polizian gli dedicò l’Orfeo,

Quanti vitelli con moderna clava

accoppa l’uomo e se li mangia? Orbene,

papa Alessandro, accoppator dabbene,

i suoi nemici, non se li mangiava.

Dunque, non mi seccar! Parole amare,

serio comento a questa fantocciata

della vita? Va’ là. Carta sprecata.

Ridi meglio, narrando, e lascia fare.

Primavera dei Terrazzi

La mia vicina, sul mattin d’aprile,

compresa ancora del tepor del letto,

esce al terrazzo, e al sol primaverile

spiega i tesori del ricolmo petto.

Ella ha piú grazia, la vicina, in quella

acconciatura che le cangia aspetto:

un camicino bianco e una gonnella

di panno lano oscura. La saluto

dal mio poggiolo dirimpetto, ed ella,

lieve inchinando il capo riccioluto,

mi risponde; poi viene al pilastrino,

su cui ride snasato un fauno arguto,

e dice: – «Come mai, caro vicino?

siete voi? sogno ancora? o com’è andata?

qual gallo v’ha cantato il mattutino?» –

Cosí, tra i fior, su la balaustrata,

dei vasi ben disposti e con amore

coltivati da lei lungo l’annata,

un grande anch’ella pare e vivo fiore;

anzi, lei sola, un fiore. A quel giardino,

giro giro, che calci di gran cuore

darei! parmi ogni vaso un cervellino

di moderno romantico poeta

che levi dal suo fango un inno fino

tra il cessin le pillaccole e la creta

per dir che piú non ama e piú non spera

alla stagion che tutto il mondo allieta.

Oh dei terrazzi magra primavera,

sciocca di nuove rime fioritura!

Mi duol che voi, maestra giardiniera,

ve ne prendiate cosí assidua cura.

Codesti fiori dall’olezzo ingrato

non vi sembrano sforzi di natura?

Due tartarughe, intanto, senza fiato,

s’inseguono sui pie’ sbiechi, in amore,

raspando il piano d’asfalto bruciato.

Cara vicina, fatemi il favore

di rivoltarle su la scaglia al sole:

non hanno alcun riguardo, alcun pudore,

brutte rocciose sceme bestiole;

sono lí lí per fare atto villano,

mentre che noi facciam solo parole:

le vedremo armeggiar nel vuoto, invano.

Luigi Pirandello: Poesia

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive O-P, Luigi Pirandello, Pirandello, Luigi, Pirandello, Luigi

L u i g i P i r a n d e l l o

(1867-1936)

L’Occhio per la Morte

Sono stato a veder l’amico morto.

Sta benone. Men brutto (ah, brutto egli era

povero amico!): e quel pallor di cera

e la calma in cui sta da savio assorto,

gli dànno or l’aria mesta e tollerante,