Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

My Last Duchess

That’s my last Duchess painted on the wall,

Looking as if she were alive. I call

That piece a wonder, now : Frà Pandolf’s hands

Worked busily a day, and there she stands.

Will’t please you sit and look at her ? I said

‘Frà Pandolf’ by design, for never read

Strangers like you that pictured countenance,

The depth and passion of its earnest glance,

But to myself they turned (since none puts by

The curtain I have drawn for you, but I)

And seemed as they would ask me, if they durst,

How such a glance came there ; so, not the first

Are you to turn and ask thus. Sir, ’t was not

Her husband’s presence only, called that spot

Of joy into the Duchess’ cheek : perhaps

Frà Pandolf chanced to say ‘Her mantle laps

Over my lady’s wrist too much,’ or ‘Paint

Must never hope to reproduce the faint

Half-flush that dies along her throat :’ such stuff

Was courtesy, she thought, and cause enough

For calling up that spot of joy. She had

A heart―how shall I say ?―too soon made glad,

Too easily impressed ; she liked whate’er

She looked on, and her looks went everywhere.

Sir, ’t was all one! My favour at her breast,

The dropping of the daylight in the West,

The bough of cherries some officious fool

Broke in the orchard for her, the white mule

She rode with round the terrace―all and each

Would draw from her alike the approving speech,

Or blush, at least. She thanked men,―good! but thanked

Somehow―I know not how―as if she ranked

My gift of a nine-hundred-years-old name

With anybody’s gift. Who’d stoop to blame

This sort of trifling? Even had you skill

In speech―(which I have not)―to make your will

Quite clear to such an one, and say, ‘Just this

Or that in you disgusts me ; here you miss,

Or there exceed the mark’―and if she let

Herself be lessoned so, nor plainly set

Her wits to yours, forsooth, and made excuse,

―E’en then would be some stooping ; and I choose

Never to stoop. Of sir, she smiled, no doubt,

Whene’er I passed her ; but who passed without

Much the same smile? This grew ; I gave commands ;

Then all smiles stopped together. There she stands

As if alive. Will’t please you rise ? We’ll meet

The company below, then. I repeat,

The Count your master’s known munificence

Is ample warrant that no just pretence

Of mine for dowry will be disallowed ;

Though his fair daughter’s self, as I avowed

At starting, is my object. Nay, we’ll go

Together down, sir. Notice Neptune, though,

Taming a sea-horse, thought a rarity,

Which Claus of Innsbruck cast in bronze for me!

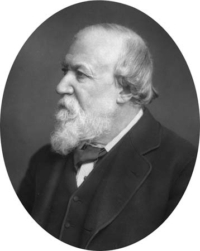

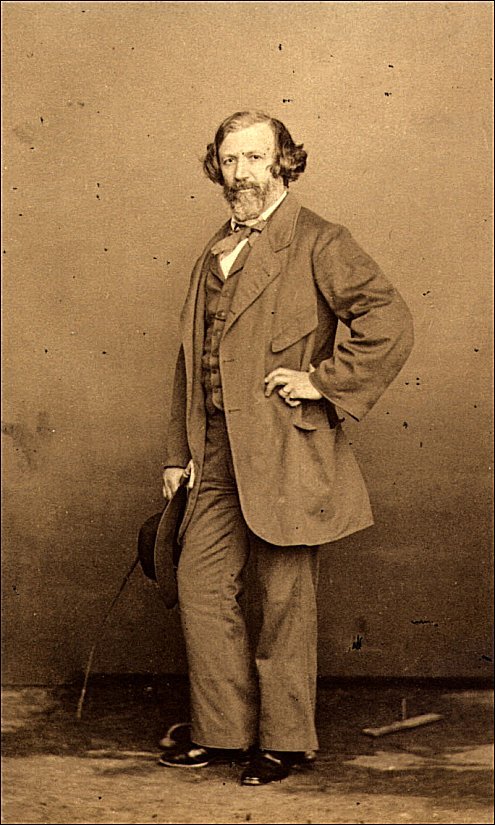

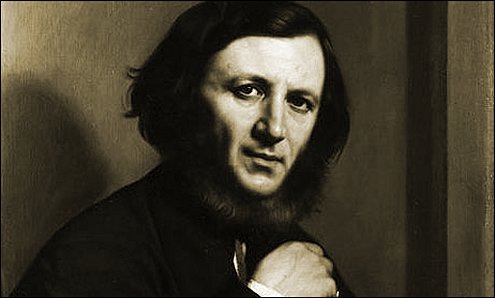

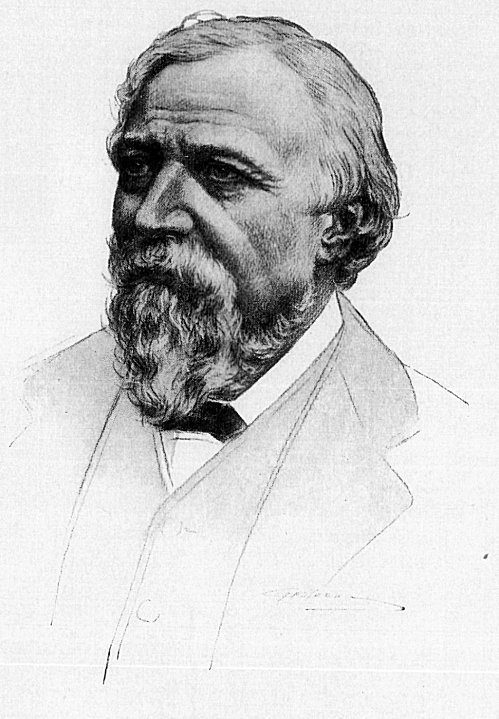

Robert Browning (1812 – 1889)

My Last Duchess

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Browning, Robert

Robert Browning

(1812-1889)

Meeting at Night

The gray sea and the long black land;

And the yellow half-moon large and low

And the startled little waves that leap

In fiery ringlets from their sleep,

As I gain the cove with pushing prow,

And quench its speed i’ the slushy sand.

Then a mile of warm sea-scented beach;

Three fields to cross till a farm appears;

A tap at the pane, the quick sharp scratch

And blue spurt of a lighted match,

And a voice less loud, through its joys and fears,

Than the two hearts beating each to each!

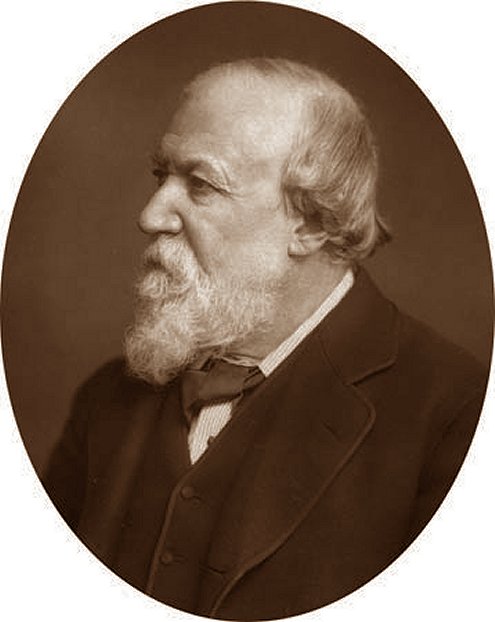

Robert Browning poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Browning, Robert

R o b e r t B r o w n i n g

(1812-1889)

The Flower’s Name

Here’s the garden she walked across,

Arm in my arm, such a short while since;

Hark, now I push its wicket, the moss

Hinders the hinges and makes them wince!

She must have reached this shrub ere she turned,

As back with that murmur the wicket swung;

For she laid the poor snail, my chance foot spurned,

To feed and forget it the leaves among.

Down this side of the gravel-walk

She went while her robe’s edge brushed the box;

And here she paused in her gracious talk

To point me a moth on the milk-white phlox.

Roses, ranged in valiant row,

I will never think that she passed you by!

She loves you, noble roses, I know;

But yonder, see, where the rock-plants lie!

This flower she stopped at, finger on lip,

Stooped over, in doubt, as settling its claim;

Till she gave me, with pride to make no slip,

Its soft meandering Spanish name.

What a name! Was it love or praise?

Speech half-asleep or song half-awake?

I must learn Spanish, one of these days,

Only for that slow sweet name’s sake.

Roses, if I live and do well,

I may bring her, one of these days,

To fix you fast with as fine a spell,

Fit you each with his Spanish phrase;

But do not detain me now; for she lingers

There, like sunshine over the ground,

And ever I see her soft white fingers

Searching after the bud she found.

Flower, you Spaniard, look that you grow not;

Stay as you are and be loved forever!

Bud, if I kiss you ’tis that you blow not;

Mind, the shut pink month opens never!

For while it pouts, her fingers wrestle,

Twinkling the audacious leaves between,

Till round they turn and down they nestle–

Is not the dear mark still to be seen?

Where I find her not, beauties vanish;

Whither I follow her, beauties flee;

Is there no method to tell her in Spanish

June’s twice June since she breathed it with me?

Come, bud, show me the least of her traces,

Treasure my lady’s lightest footfall!

–Ah, you may flout and turn up your faces–

Roses, you are not so fair after all!

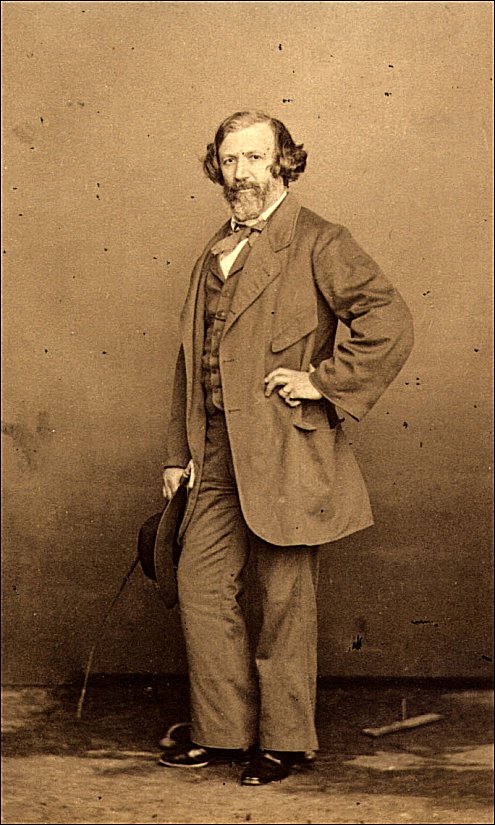

Robert Browning poetry

kemp = mag poetry magazine

More in: Browning, Robert

R o b e r t B r o w n i n g

(1812-1889)

M e m o r a b i l i a

Ah, did you once see Shelley plain,

And did he stop and speak to you,

And did you speak to him again?

How strange it seems and new!

But you were living before that,

And also you are living after;

And the memory I started at–

My starting moves your laughter!

I crossed a moor, with a name of its own

And a certain use in the world no doubt,

Yet a hand’s-breadth of it shines alone

‘Mid the blank miles round about:

For there I picked up on the heather,

And there I put inside my breast

A molted feather, an eagle-feather!

Well, I forget the rest.

.jpg)

Robert Browning poetry

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Browning, Robert

.jpg)

R o b e r t B r o w n i n g

(1812-1889)

A F a c e

If one could have that little head of hers

Painted upon a background of pale gold,

Such as the Tuscan’s early art prefers!

No shade encroaching on the matchless mold

Of those two lips, which should be opening soft

In the pure profile; not as when she laughs,

For that spoils all; but rather as if aloft

Yon hyacinth, she loves so, leaned its staff’s

Burthen of honey-colored buds to kiss

And capture ‘twixt the lips apart for this.

Then her lithe neck, three fingers might surround,

How it should waver on the pale gold ground

Up to the fruit-shaped, perfect chin it lifts!

I know, Correggio loves to mass, in rifts

Of heaven, his angel faces, orb on orb

Breaking its outline, burning shades absorb;

But these are only massed there, I should think,

Waiting to see some wonder momently

Grow out, stand full, fade slow against the sky

(That’s the pale ground you’d see this sweet face by),

All heaven, meanwhile, condensed into one eye

Which fears to lose the wonder, should it wink.

.jpg)

Robert Browning poetry

k e m p i s p o e t r y m a g a z i n e

More in: Browning, Robert

R o b e r t B r o w n i n g

(1812-1889)

Old Pictures in Florence

The morn when first it thunders in March,

The eel in the pond gives a leap, they say;

As I leaned and looked over the aloed arch

Of the villa-gate this warm March day,

No flash snapped, no dumb thunder rolled

In the valley beneath where, white and wide

And washed by the morning water-gold,

Florence lay out on the mountain-side.

River and bridge and street and square

Lay mine, as much at my beck and call,

Through the live translucent bath of air,

As the sights in a magic crystal ball.

And of all I saw and of all I praised,

The most to praise and the best to see

Was the startling bell-tower Giotto raised;

But why did it more than startle me?

Giotto, how, with that soul of yours,

Could you play me false who loved you so?

Some slights if a certain heart endures

Yet it feels, I would have your fellows know!

I’ faith, I perceive not why I should care

To break a silence that suits them best,

But the thing grows somewhat hard to bear

When I find a Giotto join the rest.

On the arch where olives overhead

Print the blue sky with twig and leaf

(That sharp-curled leaf which they never shed)

‘Twixt the aloes, I used to lean in chief,

And mark through the winter afternoons,

By a gift God grants me now and then,

In the mild decline of those suns like moons,

Who walked in Florence, besides her men.

They might chirp and chaffer, come and go

For pleasure or profit, her men alive–

My business was hardly with them, I trow,

But with empty cells of the human hive–

With the chapter-room, the cloister-porch,

The church’s apsis, aisle, or nave,

Its crypt, one fingers along with a torch,

Its face set full for the sun to shave.

Wherever a fresco peels and drops,

Wherever an outline weakens and wanes

Till the latest life in the painting stops,

Stands One whom each fainter pulse-tick pains;

One, wishful each scrap should clutch the brick,

Each tinge not wholly escape the plaster,

–A lion who dies of an ass’s kick,

The wronged great soul of an ancient Master.

For oh, this world and the wrong it does!

They are safe in heaven with their backs to it,

The Michaels and Rafaels, you hum and buzz

Round the works of, you of the little wit!

Do their eyes contract to the earth’s old scope,

Now that they see God face to face,

And have all attained to be poets, I hope?

‘Tis their holiday now, in any case.

Much they reck of your praise and you!

But the wronged great souls–can they be quit

Of a world where their work is all to do,

Where you style them, you of the little wit,

Old Master This and Early the Other,

Not dreaming that Old and New are fellows:

A younger succeeds to an elder brother,

Da Vincis derive in good time from Dellos.

And here where your praise might yield returns,

And a handsome word or two give help,

Here, after your kind, the mastiff girns

And the puppy pack of poodles yelp.

What, not a word for Stefano there,

Of brow once prominent and starry,

Called Nature’s Ape and the world’s despair

For his peerless painting? (See Vasari.)

There stands the Master. Study, my friends,

What a man’s work comes to! So he plans it,

Performs it, perfects it, makes amends

For the toiling and moiling, and then, ‘sic transit’!

Happier the thrifty blind-folk labor,

With upturned eye while the hand is busy,

Not sidling a glance at the coin of their neighbor!

‘Tis looking downward that makes one dizzy.

"If you knew their work you would deal your dole."

May I take upon me to instruct you?

When Greek Art ran and reached the goal,

Thus much had the world to boast ‘in fructu’–

The Truth of Man, as by God first spoken,

Which the actual generations garble,

Was re-uttered, and Soul (which Limbs betoken)

And Limbs (Soul informs) made new in marble.

So you saw yourself as you wished you were,

As you might have been, as you cannot be;

Earth here, rebuked by Olympus there:

And grew content in your poor degree

With your little power, by those statues’ godhead,

And your little scope, by their eyes’ full sway,

And your little grace, by their grace embodied,

And your little date, by their forms that stay.

You would fain be kinglier, say, than I am?

Even so, you will not sit like Theseus.

You would prove a model? The Son of Priam

Has yet the advantage in arms’ and knees’ use.

You’re wroth–can you slay your snake like Apollo?

You’re grieved–still Niobe’s the grander!

You live–there’s the Racers’ frieze to follow:

You die–there’s the dying Alexander.

So, testing your weakness by their strength,

Your meager charms by their rounded beauty,

Measured by Art in your breadth and length,

You learned–to submit is a mortal’s duty.

–When I say "you" ’tis the common soul,

The collective, I mean–the race of Man

That receives life in parts to live in a whole,

And grow here according to God’s clear plan.

Growth came when, looking your last on them all,

You turned your eyes inwardly one fine day

And cried with a start–What if we so small

Be greater and grander the while than they?

Are they perfect of lineament, perfect of stature?

In both, of such lower types are we

Precisely because of our wider nature;

For time, theirs–ours, for eternity.

Today’s brief passion limits their range;

It seethes with the morrow for us and more.

They are perfect–how else? they shall never change;

We are faulty–why not? we have time in store.

The Artificer’s hand is not arrested

With us; we are rough-hewn, nowise polished;

They stand for our copy, and, once invested

With all they can teach, we shall see them abolished.

‘Tis a life-long toil till our lump be leaven–

The better! What’s come to perfection perishes.

Things learned on earth we shall practice in heaven:

Works done least rapidly, Art most cherishes.

Thyself shalt afford the example, Giotto!

Thy one work, not to decrease or diminish,

Done at a stroke, was just (was it not?) "O!"

Thy great Campanile is still to finish.

Is it true that we are now, and shall be hereafter,

But what and where depend on life’s minute?

Hails heavenly cheer or infernal laughter

Our first step out of the gulf or in it?

Shall Man, such step within his endeavor,

Man’s face, have no more play and action

Than joy which is crystallized forever,

Or grief, an eternal petrifaction?

On which I conclude, that the early painters,

To cries of "Greek Art and what more wish you?"–

Replied, "To become now self-acquainters,

And paint man, man, whatever the issue!

Make new hopes shine through the flesh they fray,

New fears aggrandize the rags and tatters:

To bring the invisible full into play!

Let the visible go to the dogs–what matters?"

Give these, I exhort you, their guerdon and glory

For daring so much, before they well did it.

The first of the new, in our race’s story,

Beats the last of the old; ’tis no idle quiddit.

The worthies began a revolution,

Which if on earth you intend to acknowledge,

Why, honor them now! (ends my allocution)

Nor confer your degree when the folk leave college.

There’s a fancy some lean to and others hate–

That, when this life is ended, begins

New work for the soul in another state,

Where it strives and gets weary, loses and wins:

Where the strong and the weak, this world’s congeries,

Repeat in large what they practiced in small,

Through life after life in unlimited series;

Only the scale’s to be changed, that’s all.

Yet I hardly know. When a soul has seen

By the means of Evil that Good is best,

And, through earth and its noise, what is heaven’s serene–

When our faith in the same has stood the test–

Why, the child grown man, you burn the rod,

The uses of labor are surely done;

There remaineth a rest for the people of God;

And I have had troubles enough, for one.

But at any rate I have loved the season

Of Art’s spring-birth so dim and dewy;

My sculptor is Nicolo the Pisan,

My painter–who but Cimabue?

Nor ever was a man of them all indeed,

From these to Ghiberti and Ghirlandajo,

Could say that he missed my critic-meed.

So, now to my special grievance–heigh-ho!

Their ghosts still stand, as I said before,

Watching each fresco flaked and rasped,

Blocked up, knocked out, or whitewashed o’er:

–No getting again what the church has grasped!

The works on the wall must take their chance;

"Works never conceded to England’s thick clime!"

(I hope they prefer their inheritance

Of a bucketful of Italian quicklime.)

When they go at length, with such a shaking

Of heads o’er the old delusion, sadly

Each master his way through the black streets taking,

Where many a lost work breathes though badly–

Why don’t they bethink them of who has merited?

Why not reveal while their pictures dree

Such doom, how a captive might be out-ferreted?

Why is it they never remember me?

Not that I expect the great Bigordi,

Nor Sandro to hear me, chivalric, bellicose;

Nor the wronged Lippino; and not a word I

Say of a scrap of Fra Angelico’s;

But are you too fine, Taddeo Gaddi,

To grant me a taste of your intonaco,

Some Jerome that seeks the heaven with a sad eye?

Not a churlish saint, Lorenzo Monaco?

Could not the ghost with the close red cap,

My Pollajolo, the twice a craftsman,

Save me a sample, give me the hap

Of a muscular Christ that shows the draftsman?

No Virgin by him the somewhat petty,

Of finical touch and tempera crumbly–

Could not Alesso Baldovinetti

Contribute so much, I ask him humbly?

Margheritone of Arezzo,

With the grave-clothes garb and swaddling barret

(Why purse up mouth and beak in a pet so,

You bald old saturnine poll-clawed parrot?)

Not a poor glimmering Crucifixion,

Where in the foreground kneels the donor?

If such remain, as is my conviction,

The hoarding it does you but little honor.

They pass; for them the panels may thrill,

The tempera grow alive and tinglish;

Their pictures are left to the mercies still

Of dealers and stealers, Jews and the English,

Who, seeing mere money’s worth in their prize,

Will sell it to somebody calm as Zeno

At naked High Art, and in ecstasies

Before some clay-cold vile Carlino!

No matter for these! But Giotto, you,

Have you allowed, as the town-tongues babble it–

Oh, never! it shall not be counted true–

That a certain precious little tablet

Which Buonarroti eyed like a lover–

Was buried so long in oblivion’s womb

And, left for another than I to discover,

Turns up at last! and to whom?–to whom?

I, that have haunted the dim San Spirito,

(Or was it rather the Ognissanti?)

Patient on altar-step planting a weary toe!

Nay, I shall have it yet! ‘Detur amanti!’

My Koh-i-noor–or (if that’s a platitude)

Jewel of Giamschid, the Persian Sofi’s eye;

So, in anticipative gratitude,

What if I take up my hope and prophesy?

When the hour grows ripe, and a certain dotard

Is pitched, no parcel that needs invoicing,

To the worse side of the Mont Saint Gothard,

We shall begin by way of rejoicing;

None of that shooting the sky (blank cartridge),

Nor a civic guard, all plumes and lacquer,

Hunting Radetzky’s soul like a partridge

Over Morello with squib and cracker.

This time we’ll shoot better game and bag ’em hot–

No mere display at the stone of Dante,

But a kind of sober Witanagemot

(Ex: "Casa Guidi," ‘quod videas ante’)

Shall ponder, once Freedom restored to Florence,

How Art may return that departed with her.

Go, hated house, go each trace of the Loraine’s,

And bring us the days of Orgagna hither!

How we shall prologuize, how we shall perorate,

Utter fit things upon art and history,

Feel truth at blood-heat and falsehood at zero rate,

Make of the want of the age no mystery;

Contrast the fructuous and sterile eras,

Show–monarchy ever its uncouth cub licks

Out of the bear’s shape into Chimaera’s,

While Pure Art’s birth is still the republic’s.

Then one shall propose in a speech (curt Tuscan,

Expurgate and sober, with scarcely an "issimo,")

To end now our half-told tale of Cambuscan,

And turn the bell-tower’s alt_ to altissimo:

And find as the beak of a young beccaccia

The Campanile, the Duomo’s fit ally,

Shall soar up in gold full fifty braccia,

Completing Florence, as Florence, Italy.

Shall I be alive that morning the scaffold

Is broken away, and the long-pent fire,

Like the golden hope of the world, unbaffled

Springs from its sleep, and up goes the spire

While "God and the People" plain for its motto,

Thence the new tricolor flaps at the sky?

At least to foresee that glory of Giotto

And Florence together, the first am I!

.jpg)

Robert Browning poetry

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Browning, Robert

Robert Browning

(1812-1889)

Meeting at Night

The gray sea and the long black land;

And the yellow half-moon large and low;

And the startled little waves that leap

In fiery ringlets from their sleep,

As I gain the cove with pushing prow,

And quench its speed i’ the slushy sand.

Then a mile of warm sea-scented beach;

Three fields to cross till a farm appears;

A tap at the pane, the quick sharp scratch

And blue spurt of a lighted match,

And a voice less loud, through its joys and fears,

Than the two hearts beating each to each!

Parting at Morning

Round the cape of a sudden came the sea,

And the sun looked over the mountain’s rim;

And straight was a path of gold for him,

And the need of a world of men for me.

My Star

All that I know

Of a certain star

Is, it can throw

(Like the angled spar)

Now a dart of red,

Now a dart of blue;

Till my friends have said

They would fain see, too,

My star that dartles the red and the blue!

Then it stops like a bird; like a flower, hangs furled:

They must solace themselves with the Saturn above it.

What matter to me if their star is a world?

Mine has opened its soul to me; therefore I love it.

.jpg)

Robert Browning poetry

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Browning, Robert

R o b e r t B r o w n i n g

(1812-1889)

HOME-THOUGHTS, FROM ABROAD

Oh, to be in England

Now that April’s there,

And whoever wakes in England

Sees, some morning, unaware,

That the lowest boughs and the brushwood sheaf

Round the elm-tree hole are in tiny leaf,

While the chaffinch sings on the orchard bough

In England–now!

And after April, when May follows,

And the whitethroat builds, and all the swallows!

Hark, where my blossomed pear-tree in the hedge

Leans to the field and scatters on the clover

Blossoms and dewdrops–at the bent spray’s edge–

That’s the wise thrush; he sings each song twice over,

Lest you should think he never could recapture

The first fine careless rapture!

And though the fields look rough with hoary dew,

All will be gay when noontide wakes anew

The buttercups, the little children’s dower

–Far brighter than this gaudy melon-flower!

HOME-THOUGHTS, FROM THE SEA

Nobly, nobly Cape Saint Vincent to the Northwest died away;

Sunset ran, one glorious blood-red, reeking into Cadiz Bay;

Bluish ‘mid the burning water, full in face Trafalgar lay;

In the dimmest Northeast distance dawned Gibraltar grand and gray;

"Here and here did England help me: how can I help England?"–say,

Whoso turns as I, this evening, turn to God to praise and pray,

While Jove’s planet rises yonder, silent over Africa.

.jpg)

Robert Browning poetry

k e m p i s p o e t r y m a g a z i n e

More in: Browning, Robert

.jpg)

R o b e r t B r o w n i n g

(1812-1889)

O L y r i c L o v e

O lyric Love, half angel and half bird,

And all a wonder and a wild desire–

Boldest of hearts that ever braved the sun,

Took sanctuary within the holier blue,

And sang a kindred soul out to his face–

Yet human at the red-ripe of the heart–

When the first summons from the darkling earth

Reached thee amid thy chambers, blanched their blue,

And bared them of the glory–to drop down,

To toil for man, to suffer or to die–

This is the same voice; can thy soul know change?

Hail then, and hearken from the realms of help!

Never may I commence my song, my due

To God who best taught song by gift of thee,

Except with bent head and beseeching hand–

That still, despite the distance and the dark,

What was, again may be; some interchange

Of grace, some splendor once thy very thought,

Some benediction anciently thy smile:

–Never conclude, but raising hand and head.

Thither where eyes, that cannot reach, yet yearn

For all hope, all sustainment, all reward,

Their utmost up and on–so blessing back

In those thy realms of help, that heaven thy home,

Some whiteness which, I judge, thy face makes proud,

Some wanness where, I think, thy foot may fall!

.jpg)

Robert Browning Poetry

k e m p i s p o e t r y m a g a z i n e

More in: Browning, Robert

R o b e r t B r o w n i n g

(1812-1889)

I n T h r e e D a y s

So, I shall see her in three days

And just one night, but nights are short,

Then two long hours, and that is morn.

See how I come, unchanged, unworn!

Feel, where my life broke off from thine,

How fresh the splinters keep and fine–

Only a touch and we combine!

Too long, this time of year, the days!

But nights, at least the nights are short.

As night shows where her one moon is,

A hand’s-breadth of pure light and bliss,

So life’s night gives my lady birth

And my eyes hold her! What is worth

The rest of heaven, the rest of earth?

O loaded curls, release your store

Of warmth and scent, as once before

The tingling hair did, lights and darks

Outbreaking into fairy sparks,

When under curl and curl I pried

After the warmth and scent inside,

Through lights and darks how manifold–

The dark inspired, the light controlled!

As early Art embrowns the gold.

What great fear, should one say, “Three days

That change the world might change as well

Your fortune; and if joy delays,

Be happy that no worse befell!”

What small fear, if another says,

“Three days and one short night beside

May throw no shadow on your ways;

But years must teem with change untried,

With chance not easily defied,

With an end somewhere undescried.”

No fear!–or if a fear be born

This minute, it dies out in scorn.

Fear? I shall see her in three days

And one night, now the nights are short,

Then just two hours, and that is morn.

![]()

Robert Browning poetry

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Browning, Robert

.jpg)

R o b e r t B r o w n i n g

(1812-1889)

O n e W o r d M o r e

I

There they are, my fifty men and women

Naming me the fifty poems finished!

Take them, Love, the book and me together:

Where the heart lies, let the brain lie also.

II

Rafael made a century of sonnets,

Made and wrote them in a certain volume

Dinted with the silver-pointed pencil

Else he only used to draw Madonnas:

These, the world might view–but one, the volume.

Who that one, you ask? Your heart instructs you.

Did she live and love it all her lifetime?

Did she drop, his lady of the sonnets,

Die, and let it drop beside her pillow

Where it lay in place of Rafael’s glory,

Rafael’s cheek so duteous and so loving–

Cheek, the world was wont to hail a painter’s,

Rafael’s cheek, her love had turned a poet’s?

III

You and I would rather read that volume

(Taken to his beating bosom by it),

Lean and list the bosom-beats of Rafael,

Would we not? than wonder at Madonnas–

Her, San Sisto names, and Her, Foligno,

Her, that visits Florence in a vision,

Her, that’s left with lilies in the Louvre–

Seen by us and all the world in circle.

IV

You and I will never read that volume.

Guido Reni, like his own eye’s apple

Guarded long the treasure-book and loved it.

Guido Reni dying, all Bologna

Cried, and the world cried too, "Ours, the treasure!"

Suddenly, as rare things will, it vanished.

V

Dante once prepared to paint an angel:

Whom to please? You whisper "Beatrice."

While he mused and traced it and retraced it

(Peradventure with a pen corroded

Still by drops of that hot ink he dipped for,

When, his left hand i’ the hair o’ the wicked,

Back he held the brow and pricked its stigma,

Bit into the live man’s flesh for parchment,

Loosed him, laughed to see the writing rankle,

Let the wretch go festering through Florence)–

Dante, who loved well because he hated,

Hated wickedness that hinders loving,

Dante standing, studying his angel–

In there broke the folk of his Inferno.

Says he–"Certain people of importance"

(Such he gave his daily, dreadful line to)

"Entered and would seize, forsooth, the poet."

Says the poet–"Then I stopped my painting."

VI

You and I would rather see that angel,

Painted by the tenderness of Dante–

Would we not?–than read a fresh Inferno.

VII

You and I will never see that picture.

While he mused on love and Beatrice,

While he softened o’er his outlined angel,

In they broke, those "people of importance":

We and Bice bear the loss forever.

VIII

What of Rafael’s sonnets, Dante’s picture?

This: no artist lives and loves, that longs not

Once, and only once, and for one only

(Ah, the prize!), to find his love a language

Fit and fair and simple and sufficient–

Using nature that’s an art to others,

Not, this one time, art that’s turned his nature.

Aye, of all the artists living, loving,

None but would forego his proper dowry–

Does he paint? He fain would write a poem–

Does he write? He fain would paint a picture,

Put to proof art alien to the artist’s,

Once, and only once, and for one only,

So to be the man and leave the artist,

Gain the man’s joy, miss the artist’s sorrow.

IX

Wherefore? Heaven’s gift takes earth’s abatement!

He who smites the rock and spreads the water,

Bidding drink and live a crowd beneath him,

Even he, the minute makes immortal,

Proves, perchance, but mortal in the minute,

Desecrates, belike, the deed in doing.

While he smites, how can he but remember,

So he smote before, in such a peril,

When they stood and mocked–"Shall smiting help us?"

When they drank and sneered–"A stroke is easy!"

When they wiped their mouths and went their journey,

Throwing him for thanks–"But drought was pleasant."

Thus old memories mar the actual triumph;

Thus the doing savors of disrelish;

Thus achievement lacks a gracious somewhat;

O’er-importuned brows becloud the mandate,

Carelessness or consciousness–the gesture.

For he bears an ancient wrong about him,

Sees and knows again those phalanxed faces,

Hears, yet one time more, the ‘customed prelude–

"How shouldst thou, of all men, smite, and save us?"

Guesses what is like to prove the sequel–

"Egypt’s flesh-pots–nay, the drought was better."

X

Oh, the crowd must have emphatic warrant

Theirs, the Sinai-forehead’s cloven brilliance,

Right-arm’s rod-sweep, tongue’s imperial fiat.

Never dares the man put off the prophet.

XI

Did he love one face from out the thousands

(Were she Jethro’s daughter, white and wifely,

Were she but the Ethiopian bondslave),

He would envy yon dumb patient camel,

Keeping a reserve of scanty water

Meant to save his own life in the desert;

Ready in the desert to deliver

(Kneeling down to let his breast be opened)

Hoard and life together for his mistress.

XII

I shall never, in the years remaining,

Paint you pictures, no, nor carve you statues,

Make you music that should all-express me;

So it seems: I stand on my attainment.

This of verse alone, one life allows me;

Verse and nothing else have I to give you.

Other heights in other lives, God willing:

All the gifts from all the heights, your own, Love!

XIII

Yet a semblance of resource avails us–

Shade so finely touched, love’s sense must seize it.

Take these lines, look lovingly and nearly,

Lines I write the first time and the last time.

He who works in fresco, steals a hair-brush,

Curbs the liberal hand, subservient proudly,

Cramps his spirit, crowds its all in little,

Makes a strange art of an art familiar,

Fills his lady’s missal-marge with flowerets.

He who blows through bronze may breathe through silver,

Fitly serenade a slumbrous princess.

He who writes may write for once as I do.

XIV

Love, you saw me gather men and women,

Live or dead or fashioned by my fancy,

Enter each and all, and use their service.

Speak from every mouth–the speech, a poem.

Hardly shall I tell my joys and sorrows,

Hopes and fears, belief and disbelieving:

I am mine and yours–the rest be all men’s,

Karshish, Cleon, Norbert, and the fifty.

Let me speak this once in my true person,

Not as Lippo, Roland, or Andrea,

Though the fruit of speech be just this sentence:

Pray you, look on these my men and women,

Take and keep my fifty poems finished;

Where my heart lies, let my brain lie also!

Poor the speech; be how I speak, for all things.

XV

Not but that you know me! Lo, the moon’s self!

Here in London, yonder late in Florence,

Still we find her face, the thrice-transfigured.

Curving on a sky imbrued with color,

Drifted over Fiesole by twilight,

Came she, our new crescent of a hair’s-breadth.

Full she flared it, lamping Samminiato,

Rounder ‘twixt the cypresses and rounder,

Perfect till the nightingales applauded.

Now, a piece of her old self, impoverished,

Hard to greet, she traverses the house-roofs,

Hurries with unhandsome thrift of silver,

Goes dispiritedly, glad to finish.

XVI

What, there’s nothing in the moon noteworthy?

Nay: for if that moon could love a mortal,

Use, to charm him (so to fit a fancy),

All her magic (’tis the old sweet mythos),

She would turn a new side to her mortal,

Side unseen of herdsman, huntsman, steersman–

Blank to Zoroaster on his terrace,

Blind to Galileo on his turret,

Dumb to Homer, dumb to Keats–him, even!

Think, the wonder of the moonstruck mortal–

When she turns round, comes again in heaven,

Opens out anew for worse or better!

Proves she like some portent of an iceberg

Swimming full upon the ship it founders,

Hungry with huge teeth of splintered crystals?

Proves she as the paved work of a sapphire

Seen by Moses when he climbed the mountain?

Moses, Aaron, Nadab, and Abihu

Climbed and saw the very God, the Highest,

Stand upon the paved work of a sapphire.

Like the bodied heaven in his clearness

Shone the stone, the sapphire of that paved work,

When they ate and drank and saw God also!

XVII

What were seen? None knows, none ever shall know.

Only this is sure–the sight were other,

Not the moon’s same side, born late in Florence,

Dying now impoverished here in London.

God be thanked, the meanest of his creatures

Boasts two soul-sides, one to face the world with,

One to show a woman when he loves her!

XVIII

This I say of me, but think of you, Love!

This to you–yourself my moon of poets!

Ah, but that’s the world’s side, there’s the wonder,

Thus they see you, praise you, think they know you!

There, in turn I stand with them and praise you–

Out of my own self, I dare to phrase it.

But the best is when I glide from out them,

Cross a step or two of dubious twilight,

Come out on the other side, the novel

Silent silver lights and darks undreamed of,

Where I hush and bless myself with silence.

XIX

Oh, their Rafael of the dear Madonnas,

Oh, their Dante of the dread Inferno,

Wrote one song–and in my brain I sing it,

Drew one angel–borne, see, on my bosom.

.jpg)

Robert Browning poetry

k e m p i s p o e t r y m a g a z i n e

More in: Browning, Robert

R o b e r t B r o w n i n g

(1812-1889)

A Face

If one could have that little head of hers

Painted upon a background of pure gold,

Such as the Tuscan’s early art prefers!

No shade encroaching on the matchless mould

Of those two lips, which should be opening soft

In the pure profile; not as when she laughs,

For that spoils all: but rather as if aloft

Yon hyacinth, she loves so, leaned its staff’s

Burden of honey-colored buds to kiss

And capture ‘twixt the lips apart for this.

Then her little neck, three fingers might surround,

How it should waver on the pale gold ground

Up to the fruit-shaped, perfect chin it lifts!

I know, Correggio loves to mass, in rifts

Of heaven, his angel faces, orb on orb

Breaking its outline, burning shades absorb:

But these are only massed there, I should think,

Waiting to see some wonder momently

Grow out, stand full, fade slow against the sky

(That’s the pale ground you’d see this sweet face by),

All heaven, meanwhile, condensed into one eye

Which fears to lose the wonder, should it wink.

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Browning, Robert

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature