Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

De Dichter

Geen zomer-schaâuwe is schoon als ‘t beeld, in volle teilen,

der welv’ge melk die ront, van roerig licht ommaald.

Mijn schamel huis, waar zoel een geur van peren draalt,

weegt teerder in mijn schroom dan ‘t hele herfst-verwijlen.

En, waar van ‘t winter-dak een schone mane daalt,

‘n weifelt ijl een hele lente in hare wijle,

o mijn gezóende blik, en moe van eigen-peilen?

– Geen zoen is goed, dan die vergeten zorg verhaalt…

Aldus wie zijn geluk in ‘t noden van een teken

gelijk een geurig brood meewarig-blij durft breken,

en nut de zuurste zemel-korst in heil’ge waan;

om bij het heil dat weende en ‘t vreemde leed dat lachte,

en in de hoede van uw deemstren, o Gedachte,

eens, als een schone vraag, glim-lachend heen te gaan.

De Boom-Gaard der Vogelen en der Vruchten (1903 – 1905)

Karel van de Woestijne

(1878 – 1929)

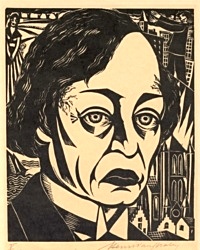

De Dichter

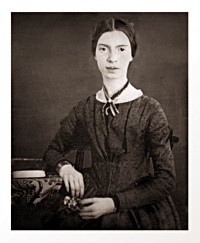

Portret van Karel van de Woestijne (1937) door Henri van Straten (1892 – 1944)

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive W-X, Archive W-X, Woestijne, Karel van de

Farewell!

If Ever Fondest Prayer

Farewell! if ever fondest prayer

For other’s weal availed on high,

Mine will not all be lost in air,

But waft thy name beyond the sky.

‘Twere vain to speak, to weep, to sigh:

Oh! more than tears of blood can tell,

When wrung from guilt’s expiring eye,

Are in that word – Farewell! – Farewell!

These lips are mute, these eyes are dry;

But in my breast and in my brain,

Awake the pangs that pass not by,

The thought that ne’er shall sleep again.

My soul nor deigns nor dares complain,

Though grief and passion there rebel;

I only know we loved in vain –

I only feel – Farewell! – Farewell!

George Gordon Byron

(1788 – 1824)

Farewell! If Ever Fondest Prayer

(Poem)

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Archive A-B, Byron, Lord

A MATTER OF DOCTRINE

There was great excitement in Miltonville over the advent of a most eloquent and convincing minister from the North.

The beauty about the Rev. Thaddeus Warwick was that he was purely and simply a man of the doctrine. He had no emotions, his sermons were never matters of feeling; but he insisted so strongly upon the constant presentation of the tenets of his creed that his presence in a town was always marked by the enthusiasm and joy of religious disputation.

The beauty about the Rev. Thaddeus Warwick was that he was purely and simply a man of the doctrine. He had no emotions, his sermons were never matters of feeling; but he insisted so strongly upon the constant presentation of the tenets of his creed that his presence in a town was always marked by the enthusiasm and joy of religious disputation.

The Rev. Jasper Hayward, coloured, was a man quite of another stripe. With him it was not so much what a man held as what he felt. The difference in their characteristics, however, did not prevent him from attending Dr. Warwick’s series of sermons, where, from the vantage point of the gallery, he drank in, without assimilating, that divine’s words of wisdom.

Especially was he edified on the night that his white brother held forth upon the doctrine of predestination. It was not that he understood it at all, but that it sounded well and the words had a rich ring as he champed over them again and again.

Mr. Hayward was a man for the time and knew that his congregation desired something new, and if he could supply it he was willing to take lessons even from a white co-worker who had neither “de spi’it ner de fiah.” Because, as he was prone to admit to himself, “dey was sump’in’ in de unnerstannin’.”

He had no idea what plagiarism is, and without a single thought of wrong, he intended to reproduce for his people the religious wisdom which he acquired at the white church. He was an innocent beggar going to the doors of the well-provided for cold spiritual victuals to warm over for his own family. And it would not be plagiarism either, for this very warming-over process would save it from that and make his own whatever he brought. He would season with the pepper of his homely wit, sprinkle it with the salt of his home-made philosophy, then, hot with the fire of his crude eloquence, serve to his people a dish his very own. But to the true purveyor of original dishes it is never pleasant to know that someone else holds the secret of the groundwork of his invention.

It was then something of a shock to the Reverend Mr. Hayward to be accosted by Isaac Middleton, one of his members, just as he was leaving the gallery on the night of this most edifying of sermons.

Isaac laid a hand upon his shoulder and smiled at him benevolently.

“How do, Brothah Hayward,” he said, “you been sittin’ unner de drippin’s of de gospel, too?”

“Yes, I has been listenin’ to de wo’ds of my fellow-laborah in de vineya’d of de Lawd,” replied the preacher with some dignity, for he saw vanishing the vision of his own glory in a revivified sermon on predestination.

Isaac linked his arm familiarly in his pastor’s as they went out upon the street.

“Well, what you t’ink erbout pre-o’dination an’ fo’-destination any how?”

“It sutny has been pussented to us in a powahful light dis eve’nin’.”

“Well, suh, hit opened up my eyes. I do’ know when I’s hyeahed a sehmon dat done my soul mo’ good.”

“It was a upliftin’ episode.”

“Seem lak ‘co’din’ to de way de brothah ‘lucidated de matter to-night dat evaht’ing done sot out an’ cut an’ dried fu’ us. Well dat’s gwine to he’p me lots.”

“De gospel is allus a he’p.”

“But not allus in dis way. You see I ain’t a eddicated man lak you, Brothah Hayward.”

“We can’t all have de same ‘vantages,” the preacher condescended. “But what I feels, I feels, an’ what I unnerstan’s, I unnerstan’s. The Scripture tell us to get unnerstannin’.”

“Well, dat’s what I’s been a-doin’ to-night. I’s been a-doubtin’ an’ a-doubtin’, a-foolin’ erroun’ an’ wonderin’, but now I unnerstan’.”

“‘Splain yo’se’f, Brothah Middleton,” said the preacher.

“Well, suh, I will to you. You knows Miss Sally Briggs? Huh, what say?”

The Reverend Hayward had given a half discernible start and an exclamation had fallen from his lips.

“What say?” repeated his companion.

“I knows de sistah ve’y well, she bein’ a membah of my flock.”

“Well, I been gwine in comp’ny wit dat ooman fu’ de longes’. You ain’t nevah tasted none o’ huh cookin’, has you?”

“I has ‘sperienced de sistah’s puffo’mances in dat line.”

“She is the cookin’est ooman I evah seed in all my life, but howsomedever, I been gwine all dis time an’ I ain’ nevah said de wo’d. I nevah could git clean erway f’om huh widout somep’n’ drawin’ me back, an’ I didn’t know what hit was.”

The preacher was restless.

“Hit was des dis away, Brothah Hayward, I was allus lingerin’ on de brink, feahful to la’nch away, but now I’s a-gwine to la’nch, case dat all dis time tain’t been nuffin but fo’-destination dat been a-holdin’ me on.”

“Ahem,” said the minister; “we mus’ not be in too big a hu’y to put ouah human weaknesses upon some divine cause.”

“I ain’t a-doin’ dat, dough I ain’t a-sputin’ dat de lady is a mos’ oncommon fine lookin’ pusson.”

“I has only seed huh wid de eye of de spi’it,” was the virtuous answer, “an’ to dat eye all t’ings dat are good are beautiful.”

“Yes, suh, an’ lookin’ wid de cookin’ eye, hit seem lak’ I des fo’destinated fu’ to ma’y dat ooman.”

“You say you ain’t axe huh yit?”

“Not yit, but I’s gwine to ez soon ez evah I gets de chanst now.”

“Uh, huh,” said the preacher, and he began to hasten his steps homeward.

“Seems lak you in a pow’ful hu’y to-night,” said his companion, with some difficulty accommodating his own step to the preacher’s masterly strides. He was a short man and his pastor was tall and gaunt.

“I has somp’n’ on my min,’ Brothah Middleton, dat I wants to thrash out to-night in de sollertude of my own chambah,” was the solemn reply.

“Well, I ain’ gwine keep erlong wid you an’ pestah you wid my chattah, Brothah Hayward,” and at the next corner Isaac Middleton turned off and went his way, with a cheery “so long, may de Lawd set wid you in yo’ meddertations.”

“So long,” said his pastor hastily. Then he did what would be strange in any man, but seemed stranger in so virtuous a minister. He checked his hasty pace, and, after furtively watching Middleton out of sight, turned and retraced his steps in a direction exactly opposite to the one in which he had been going, and toward the cottage of the very Sister Griggs concerning whose charms the minister’s parishioner had held forth.

It was late, but the pastor knew that the woman whom he sought was industrious and often worked late, and with ever increasing eagerness he hurried on. He was fully rewarded for his perseverance when the light from the window of his intended hostess gleamed upon him, and when she stood in the full glow of it as the door opened in answer to his knock.

“La, Brothah Hayward, ef it ain’t you; howdy; come in.”

“Howdy, howdy, Sistah Griggs, how you come on?”

“Oh, I’s des tol’able,” industriously dusting a chair. “How’s yo’se’f?”

“I’s right smaht, thankee ma’am.”

“W’y, Brothah Hayward, ain’t you los’ down in dis paht of de town?”

“No, indeed, Sistah Griggs, de shep’erd ain’t nevah los’ no whaih dey’s any of de flock.” Then looking around the room at the piles of ironed clothes, he added: “You sutny is a indust’ious ooman.”

“I was des ’bout finishin’ up some i’onin’ I had fu’ de white folks,” smiled Sister Griggs, taking down her ironing-board and resting it in the corner. “Allus when I gits thoo my wo’k at nights I’s putty well tiahed out an’ has to eat a snack; set by, Brothah Hayward, while I fixes us a bite.”

“La, sistah, hit don’t skacely seem right fu’ me to be a-comin’ in hyeah lettin’ you fix fu’ me at dis time o’ night, an’ you mighty nigh tuckahed out, too.”

“Tsch, Brothah Hayward, taint no ha’dah lookin’ out fu’ two dan it is lookin’ out fu’ one.”

Hayward flashed a quick upward glance at his hostess’ face and then repeated slowly, “Yes’m, dat sutny is de trufe. I ain’t nevah t’ought o’ that befo’. Hit ain’t no ha’dah lookin’ out fu’ two dan hit is fu’ one,” and though he was usually an incessant talker, he lapsed into a brown study.

Be it known that the Rev. Mr. Hayward was a man of a very level head, and that his bachelorhood was a matter of economy. He had long considered matrimony in the light of a most desirable estate, but one which he feared to embrace until the rewards for his labours began looking up a little better. But now the matter was being presented to him in an entirely different light. “Hit ain’t no ha’dah lookin’ out fu’ two dan fu’ one.” Might that not be the truth after all. One had to have food. It would take very little more to do for two. One had to have a home to live in. The same house would shelter two. One had to wear clothes. Well, now, there came the rub. But he thought of donation parties, and smiled. Instead of being an extravagance, might not this union of two beings be an economy? Somebody to cook the food, somebody to keep the house, and somebody to mend the clothes.

His reverie was broken in upon by Sally Griggs’ voice. “Hit do seem lak you mighty deep in t’ought dis evenin’, Brothah Hayward. I done spoke to you twicet.”

“Scuse me, Sistah Griggs, my min’ has been mighty deeply ‘sorbed in a little mattah o’ doctrine. What you say to me?”

“I say set up to the table an’ have a bite to eat; tain’t much, but ‘sich ez I have’—you know what de ‘postle said.”

The preacher’s eyes glistened as they took in the well-filled board. There was fervour in the blessing which he asked that made amends for its brevity. Then he fell to.

Isaac Middleton was right. This woman was a genius among cooks. Isaac Middleton was also wrong. He, a layman, had no right to raise his eyes to her. She was the prize of the elect, not the quarry of any chance pursuer. As he ate and talked, his admiration for Sally grew as did his indignation at Middleton’s presumption.

Meanwhile the fair one plied him with delicacies, and paid deferential attention whenever he opened his mouth to give vent to an opinion. An admirable wife she would make, indeed.

At last supper was over and his chair pushed back from the table. With a long sigh of content, he stretched his long legs, tilted back and said: “Well, you done settled de case ez fur ez I is concerned.”

“What dat, Brothah Hayward?” she asked.

“Well, I do’ know’s I’s quite prepahed to tell you yit.”

“Hyeah now, don’ you remembah ol’ Mis’ Eve? Taint nevah right to git a lady’s cur’osity riz.”

“Oh, nemmine, nemmine, I ain’t gwine keep yo’ cur’osity up long. You see, Sistah Griggs, you done ‘lucidated one p’int to me dis night dat meks it plumb needful fu’ me to speak.”

She was looking at him with wide open eyes of expectation.

“You made de ’emark to-night, dat it ain’t no ha’dah lookin’ out aftah two dan one.”

“Oh, Brothah Hayward!”

“Sistah Sally, I reckernizes dat, an’ I want to know ef you won’t let me look out aftah we two? Will you ma’y me?”

She picked nervously at her apron, and her eyes sought the floor modestly as she answered, “Why, Brothah Hayward, I ain’t fittin’ fu’ no sich eddicated man ez you. S’posin’ you’d git to be pu’sidin’ elder, er bishop, er somp’n’ er othah, whaih’d I be?”

He waved his hand magnanimously. “Sistah Griggs, Sally, whatevah high place I may be fo’destined to I shall tek my wife up wid me.”

This was enough, and with her hearty yes, the Rev. Mr. Hayward had Sister Sally close in his clerical arms. They were not through their mutual felicitations, which were indeed so enthusiastic as to drown the sound of a knocking at the door and the ominous scraping of feet, when the door opened to admit Isaac Middleton, just as the preacher was imprinting a very decided kiss upon his fiancee’s cheek.

“Wha’—wha'” exclaimed Middleton.

The preacher turned. “Dat you, Isaac?” he said complacently. “You must ‘scuse ouah ‘pearance, we des got ingaged.”

The fair Sally blushed unseen.

“What!” cried Isaac. “Ingaged, aftah what I tol’ you to-night.” His face was a thundercloud.

“Yes, suh.”

“An’ is dat de way you stan’ up fu’ fo’destination?”

This time it was the preacher’s turn to darken angrily as he replied, “Look a-hyeah, Ike Middleton, all I got to say to you is dat whenevah a lady cook to please me lak dis lady do, an’ whenevah I love one lak I love huh, an’ she seems to love me back, I’s a-gwine to pop de question to huh, fo’destination er no fo’destination, so dah!”

The moment was pregnant with tragic possibilities. The lady still stood with bowed head, but her hand had stolen into her minister’s. Isaac paused, and the situation overwhelmed him. Crushed with anger and defeat he turned toward the door.

On the threshold he paused again to say, “Well, all I got to say to you, Hayward, don’ you nevah talk to me no mor’ nuffin’ ’bout doctrine!”

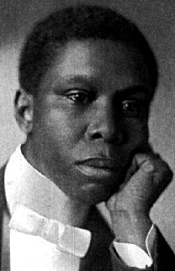

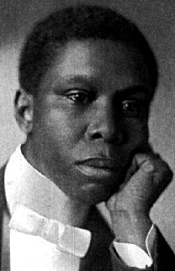

Paul Laurence Dunbar

(1872 – 1906)

A Matter Of Doctrine

From The Heart Of Happy Hollow, a collection of short stories reprinted in 1904 by Dodd, Mead and Company, New York.

Short Story

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: *Archive African American Literature, Archive C-D, Archive C-D, Dunbar, Paul Laurence, Dunbar, Paul Laurence, Paul Laurence Dunbar, Paul Laurence Dunbar

Selfie

van Gerrit Achterberg

Hoe zal nu in het huis de stilte zijn?

Val ik tezamen met uw lijn?

Mijn ledematen worden van ivoor.

Ik ben bij u gekomen, binnendoor.

Nooit was ik zo geheel en zo bijeen

terechtgekomen, ogen wijd uiteen.

Ontschorste bomen liggen aan de kant.

God heeft een buiten- en een binnenkant.

Bert Bevers

Hoe zal nu in het huis de stilte zijn? is een sample uit Distantie

Val ik tezamen met uw lijn? is een sample uit 13

Mijn ledematen worden van ivoor. is een sample uit Smaragd

Ik ben bij u gekomen, binnendoor. is een sample uit Oculair

Nooit was ik zo geheel en zo bijeen. is een sample uit Tracé

Terechtgekomen, ogen wijd uiteen is een sample uit Lucifer

Ontschorste bomen liggen aan de kant is een bijna-sample uit Station

God heeft een buiten- en een binnenkant. is een sample uit Reflexie

Selfie van Gerrit Achterberg

Verschenen in Je tikt er tegen en het zingt, Demer Uitgeverij, Leusden, 2015

Bert Bevers is a poet and writer who lives and works in Antwerp (Be)

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Achterberg, Gerrit, Archive A-B, Archive A-B, Bevers, Bert

Er komt iemand bij mij

Er komt iemand bij mij, die ‘k nimmer zag,

en uit-der-mate vriendlijk, die mij zegt:

‘Gij weet, ik berg iemand in mijne woon.

Neen: er verbergt zich iemand in mijn woon.

Ik zie hem niet, maar ben in hem begaan.

Ik ken hem, en hij is mijn liefst bezit…’

– Ik durf niet zeggen dat die vreemdling liegt.

Ik durf niet zeggen dat zijn gast de mijne is. Ach!

ik durf niet zèggen dat hij niet bestaat, misschien.

Want hij bestaat in mij.

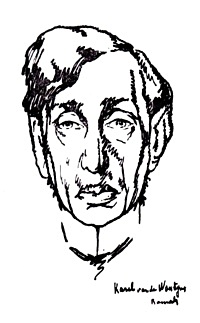

Karel van de Woestijne

(1878 – 1929)

Er komt iemand bij mij

Portret: Karel van de Woestijne, Ramah – Journal Het Roode Zeil, 15 April 1920

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive W-X, Archive W-X, Woestijne, Karel van de

THE INTERFERENCE OF PATSY ANN

Patsy Ann Meriweather would have told you that her father, or more properly her “pappy,” was a “widover,” and she would have added in her sad little voice, with her mournful eyes upon you, that her mother had “bin daid fu’ nigh onto fou’ yeahs.” Then you could have wept for Patsy, for her years were only thirteen now, and since the passing away of her mother she had been the little mother for her four younger brothers and sisters, as well as her father’s house-keeper.

But Patsy Ann never complained; she was quite willing to be all that she had been until such time as Isaac and Dora, Cassie and little John should be old enough to care for themselves, and also to lighten some of her domestic burdens. She had never reckoned upon any other manner of release. In fact her youthful mind was not able to contemplate the possibility of any other manner of change. But the good women of Patsy’s neighbourhood were not the ones to let her remain in this deplorable state of ignorance. She was to be enlightened as to other changes that might take place in her condition, and of the unspeakable horrors that would transpire with them.

But Patsy Ann never complained; she was quite willing to be all that she had been until such time as Isaac and Dora, Cassie and little John should be old enough to care for themselves, and also to lighten some of her domestic burdens. She had never reckoned upon any other manner of release. In fact her youthful mind was not able to contemplate the possibility of any other manner of change. But the good women of Patsy’s neighbourhood were not the ones to let her remain in this deplorable state of ignorance. She was to be enlightened as to other changes that might take place in her condition, and of the unspeakable horrors that would transpire with them.

It was upon the occasion that little John had taken it into his infant head to have the German measles just at the time that Isaac was slowly recovering from the chicken-pox. Patsy Ann’s powers had been taxed to the utmost, and Mrs. Caroline Gibson had been called in from next door to superintend the brewing of the saffron tea, and for the general care of the fretful sufferer.

To Patsy Ann, then, in ominous tone, spoke this oracle. “Patsy Ann, how yo’ pappy doin’ sence Matildy died?” “Matildy” was the deceased wife.

“Oh, he gittin’ ‘long all right. He was mighty broke up at de fus’, but he ‘low now dat de house go on de same’s ef mammy was a-livin’.”

“Oom huh,” disdainfully; “Oom huh. Yo’ mammy bin daid fou’ yeahs, ain’t she?”

“Yes’m; mighty nigh.”

“Oom huh; fou’ yeahs is a mighty long time fu’ a colo’d man to wait; but we’n he do wait dat long, hit’s all de wuss we’n hit do come.”

“Pap bin wo’kin right stiddy at de brick-ya’d,” said Patsy, in loyal defence against some vaguely implied accusation, “an’ he done put some money in de bank.”

“Bad sign, bad sign,” and Mrs. Gibson gave her head a fearsome shake.

But just then the shrill voice of little John calling for attention drew her away and left Patsy Ann to herself and her meditations.

What could this mean?

When that lady had finished ministering to the sick child and returned, Patsy Ann asked her, “Mis’ Gibson, what you mean by sayin’ ‘bad sign, bad sign?'”

Again the oracle shook her head sagely. Then she answered, “Chil’, you do’ know de dev’ment dey is in dis worl’.”

“But,” retorted the child, “my pappy ain’ up to no dev’ment, ‘case he got ‘uligion an’ bin baptised.”

“Oom-m,” groaned Sistah Gibson, “dat don’ mek a bit o’ diffunce. Who is any mo’ ma’yin’ men den de preachahs demse’ves? W’y Brothah ‘Lias Scott done tempted matermony six times a’ready, an’ ‘s lookin’ roun’ fu’ de sebent, an’ he’s a good man, too.”

“Ma’yin’,” said Patsy breathlessly.

“Yes, honey, ma’yin’, an’ I’s afeared yo’ pappy’s got notions in his haid, an’ w’en a widower git gals in his haid dey ain’ no use a-pesterin’ wid ’em, ‘case dey boun’ to have dey way.”

“Ma’yin’,” said Patsy to herself reflectively. “Ma’yin’.” She knew what it meant, but she had never dreamed of the possibility of such a thing in connection with her father. “Ma’yin’,” and yet the idea of it did not seem so very unalluring.

She spoke her thoughts aloud.

“But ef pap ‘u’d ma’y, Mis’ Gibson, den I’d git a chanct to go to school. He allus sayin’ he mighty sorry ’bout me not goin’.”

“Dah now, dah now,” cried the woman, casting a pitying glance at the child, “dat’s de las’ t’ing. He des a feelin’ roun’ now. You po’, ign’ant, mothahless chil’. You ain’ nevah had no step-mothah, an’ you don’ know what hit means.”

“But she’d tek keer o’ the chillen,” persisted Patsy.

“Sich tekin’ keer of ’em ez hit ‘u’d be. She’d keer fu’ ’em to dey graves. Nobody cain’t tell me nuffin ’bout step-mothahs, case I knows ’em. Dey ain’ no ooman goin’ to tek keer o’ nobody else’s chile lak she’d tek keer o’ huh own,” and Patsy felt a choking come into her throat and a tight sensation about her heart while she listened as Mrs. Gibson regaled her with all the choice horrors that are laid at the door of step-mothers.

From that hour on, one settled conviction took shape and possessed Patsy Ann’s mind; never, if she could help it, would she run the risk of having a step-mother. Come what may, let her be compelled to do what she might, let the hope of school fade from her sight forever and a day—but no step-mother should ever cast her baneful shadow over Patsy Ann’s home.

Experience of life had made her wise for her years, and so for the time she said nothing to her father; but she began to watch him with wary eyes, his goings out and his comings in, and to attach new importance to trifles that had passed unnoticed before by her childish mind.

For instance, if he greased or blacked his boots before going out of an evening her suspicions were immediately aroused and she saw dim visions of her father returning, on his arm the terrible ogress whom she had come to know by the name of step-mother.

Mrs. Gibson’s poison had worked well and rapidly. She had thoroughly inoculated the child’s mind with the step-mother virus, but she had not at the same time made the parent widow-proof, a hard thing to do at best. So it came to pass that with a mysterious horror growing within her, Patsy Ann saw her father black his boots more and more often and fare forth o’ nights and Sunday afternoons.

Finally her little heart could contain its sorrow no longer, and one night when he was later than usual she could not sleep. So she slipped out of bed, turned up the light, and waited for him, determined to have it out, then and there.

He came at last and was all surprise to meet the solemn, round eyes of his little daughter staring at him from across the table.

“W’y, lady gal,” he exclaimed, “what you doin’ up at ‘his time?”

“I sat up fu’ you. I got somep’n’ to ax you, pappy.” Her voice quivered and he snuggled her up in his arms.

“What’s troublin’ my little lady gal now? Is de chillen bin bad?”

She laid her head close against his big breast, and the tears would come as she answered, “No, suh; de chillen bin ez good az good could be, but oh, pappy, pappy, is you got gal in yo’ haid an’ a-goin’ to bring me a step-mothah?”

He held her away from him almost harshly and gazed at her as he queried, “W’y, you po’ baby, you! Who’s bin puttin’ dis hyeah foolishness in yo’ haid?” Then his laugh rang out as he patted her head and drew her close to him again. “Ef yo’ pappy do bring a step-mothah into dis house, Gawd knows he’ll bring de right kin’.”

“Dey ain’t no right kin’,” answered Patsy.

“You don’ know, baby; you don’ know. Go to baid an’ don’ worry.”

He sat up a long time watching the candle sputter, then he pulled off his boots and tiptoed to Patsy’s bedside. He leaned over her. “Po’ little baby,” he said; “what do she know about a step-mothah?” And Patsy saw him and heard him, for she was awake then, and far into the night.

In the eyes of the child her father stood convicted. He had “gal in his haid,” and was going to bring her a step-mother; but it would never be; her resolution was taken.

She arose early the next morning and after getting her father off to work as usual, she took the children into hand. First she scrubbed them assiduously, burnishing their brown faces until they shone again. Then she tussled with their refractory locks, and after that she dressed them out in all the bravery of their best clothes.

Meanwhile her tears were falling like rain, though her lips were shut tight. The children off her mind, she turned her attention to her own toilet, which she made with scrupulous care. Then taking a small tin-type of her mother from the bureau drawer, she put it in her bosom, and leading her little brood she went out of the house, locking the door behind her and placing the key, as was her wont, under the door-step.

Outside she stood for a moment or two, undecided, and then with one long, backward glance at her home she turned and went up the street. At the first corner she paused again, spat in her hand and struck the watery globule with her finger. In the direction the most of the spittle flew, she turned. Patsy Ann was fleeing from home and a step-mother, and Fate had decided her direction for her, even as Mrs. Gibson’s counsels had directed her course.

The child had no idea where she was going. She knew no one to whom she might turn in her distress. Not even with Mrs. Gibson would she be safe from the horror which impended. She had but one impulse in her mind and that was to get beyond the reach of the terrible woman, or was it a monster? who was surely coming after her. On and on she walked through the town with her little band trudging bravely along beside her. People turned to look at the funny group and smiled good-naturedly as they passed, and one man, a little more amused than the rest, shouted after them, “Where you goin’, sis, with that orphan’s home?”

But Patsy Ann’s dignity was impregnable. She walked on with her head in the air, the desire for safety tugging at her heart.

The hours passed and the gentle coolness of morning turned into the fierce heat of noon, and still with frequent rests they trudged on, Patsy ever and anon using her divining hand, unconscious that she was doubling and redoubling on her tracks. When the whistles blew for twelve she got her little brood into the shade of a poplar tree and set them down to the lunch which, thoughtful little mother that she was, she had brought with her. After that they all stretched themselves out on the grass that bordered the sidewalk, for all the children were tired out, and baby John was both sleepy and cross. Even Patsy Ann drowsed and finally dropped into the deep slumber of childhood. They looked too peaceful and serene for passers-by to bother them, and so they slept and slept.

It was past three o’clock when the little guardian awakened with a start, and shook her charges into activity. John wept a little at first, but after a while took up his journey bravely with the rest.

She had just turned into a side street, discouraged and bewildered, when the round face of a coloured woman standing in the doorway of a whitewashed cottage caught her eye and attention. Once more she paused and consulted her watery oracle, then turned to encounter the gaze of the round-faced woman. The oracle had spoken and she turned into the yard.

“Whaih you goin’, honey? You sut’ny look lak you plumb tukahed out. Come in an’ tell me all ’bout yo’se’f, you po’ little t’ing. Dese yo’ little brothas an’ sistahs?”

“Yes’m,” said Patsy Ann.

“W’y, chil’, whaih you goin’?”

“I don’ know,” was the truthful answer.

“You don’ know? Whaih you live?”

“Oh, I live down on Douglas Street,” said Patsy Ann, “an’ I’s runnin’ away f’om home an’ my step-mothah.”

The woman looked keenly at her.

“What yo’ name?” she said.

“My name’s Patsy Ann Meriweather.”

“An’ is yo’ got a step-mothah?”

“No,” said Patsy Ann, “I ain’ got none now, but I’s sut’ny ‘spectin’ one.”

“What you know ’bout step-mothahs, honey?”

“Mis’ Gibson tol’ me. Dey sho’ly is awful, missus, awful.”

“Mis’ Gibson ain’ tol’ you right, honey. You come in hyeah and set down. You ain’ nothin’ mo’ dan a baby yo’se’f, an’ you ain’ got no right to be trapsein’ roun’ dis away.”

Have you ever eaten muffins? Have you eaten bacon with onions? Have you drunk tea? Have you seen your little brother John taken up on a full bosom and rocked to sleep in the most motherly way, with the sweetness and tenderness that only a mother can give? Well, that was Patsy Ann’s case to-night.

And then she laid them along like ten-pins crosswise of her bed and sat for a long time thinking.

To Maria Adams about six o’clock that night came a troubled and disheartened man. It was no less a person than Patsy Ann’s father.

“Maria! Maria! What shall I do? Somebody don’ stole all my chillen.”

Maria, strange to say, was a woman of few words.

“Don’ you bothah ’bout de chillen,” she said, and she took him by the hand and led him to where the five lay sleeping calmly across the bed.

“Dey was runnin’ f’om home an’ dey step-mothah,” said she.

“Dey run hyeah f’om a step-mothah an’ foun’ a mothah.” It was a tribute and a proposal all in one.

When Patsy Ann awakened, the matter was explained to her, and with penitent tears she confessed her sins.

“But,” she said to Maria Adams, “ef you’s de kin’ of fo’ks dat dey mek step-mothahs out o’ I ain’ gwine to bothah my haid no mo’.”

Paul Laurence Dunbar

(1872 – 1906)

The Interference Of Patsy Ann. Short Story

From The Heart Of Happy Hollow, a collection of short stories reprinted in 1904 by Dodd, Mead and Company, New York.

Short Story

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive C-D, Archive C-D, Dunbar, Paul Laurence, Dunbar, Paul Laurence, Paul Laurence Dunbar, Paul Laurence Dunbar

Chanson de grand-père

Dansez, les petites filles,

Toutes en rond.

En vous voyant si gentilles,

Les bois riront.

Dansez, les petites reines,

Toutes en rond.

Les amoureux sous les frênes

S’embrasseront.

Dansez, les petites folles,

Toutes en rond.

Les bouquins dans les écoles

Bougonneront.

Dansez, les petites belles,

Toutes en rond.

Les oiseaux avec leurs ailes

Applaudiront.

Dansez, les petites fées,

Toutes en rond.

Dansez, de bleuets coiffées,

L’aurore au front.

Dansez, les petites femmes,

Toutes en rond.

Les messieurs diront aux dames

Ce qu’ils voudront.

Victor Hugo

(1802-1885)

Chanson de grand-père

(Poème)

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive G-H, Archive G-H, Hugo, Victor, Victor Hugo

Il fait froid

L’hiver blanchit le dur chemin

Tes jours aux méchants sont en proie.

La bise mord ta douce main ;

La haine souffle sur ta joie.

La neige emplit le noir sillon.

La lumière est diminuée…

Ferme ta porte à l’aquilon !

Ferme ta vitre à la nuée !

Et puis laisse ton coeur ouvert !

Le coeur, c’est la sainte fenêtre.

Le soleil de brume est couvert ;

Mais Dieu va rayonner peut-être !

Doute du bonheur, fruit mortel ;

Doute de l’homme plein d’envie ;

Doute du prêtre et de l’autel ;

Mais crois à l’amour, ô ma vie !

Crois à l’amour, toujours entier,

Toujours brillant sous tous les voiles !

A l’amour, tison du foyer !

A l’amour, rayon des étoiles !

Aime, et ne désespère pas.

Dans ton âme, où parfois je passe,

Où mes vers chuchotent tout bas,

Laisse chaque chose à sa place.

La fidélité sans ennui,

La paix des vertus élevées,

Et l’indulgence pour autrui,

Eponge des fautes lavées.

Dans ta pensée où tout est beau,

Que rien ne tombe ou ne recule.

Fais de ton amour ton flambeau.

On s’éclaire de ce qui brûle.

A ces démons d’inimitié

Oppose ta douceur sereine,

Et reverse leur en pitié

Tout ce qu’ils t’ont vomi de haine.

La haine, c’est l’hiver du coeur.

Plains-les ! mais garde ton courage.

Garde ton sourire vainqueur ;

Bel arc-en-ciel, sors de l’orage !

Garde ton amour éternel.

L’hiver, l’astre éteint-il sa flamme ?

Dieu ne retire rien du ciel ;

Ne retire rien de ton âme !

Victor Hugo

(1802-1885)

Il fait froid

(Poème)

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive G-H, Archive G-H, Hugo, Victor, Victor Hugo

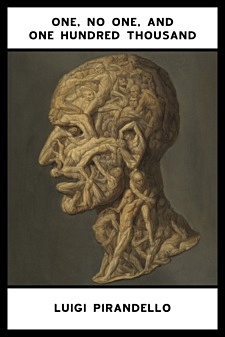

Luigi Pirandello’s extraordinary final novel begins when Vitangelo Moscarda’s wife remarks that Vitangelo’s nose tilts to the right.

This commonplace interaction spurs the novel’s unemployed, wealthy narrator to examine himself, the way he perceives others, and the ways that others perceive him.

This commonplace interaction spurs the novel’s unemployed, wealthy narrator to examine himself, the way he perceives others, and the ways that others perceive him.

At first he only notices small differences in how he sees himself and how others do; but his self-examination quickly becomes relentless, dizzying, leading to often darkly comic results as Vitangelo decides that he must demolish that version of himself that others see.

Pirandello said of his 1926 novel that it “deals with the disintegration of the personality. It arrives at the most extreme conclusions, the farthest consequences.” Indeed, its unnerving humor and existential dissection of modern identity find counterparts in Samuel Beckett’s Molloy trilogy and the works of Thomas Bernhard and Vladimir Nabokov.

Luigi Pirandello (1867-1936) was an Italian author, who was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1934 for his “bold and brilliant renovation of the drama and the stage.” Pirandello’s works include novels, hundreds of short stories, and plays. Pirandello’s plays are often seen as forerunners for the theatre of the absurd.

One, No One, and One Hundred Thousand

Luigi Pirandello

Translated by William Weaver

Publisher Spurl Editions

Format Paperback

218 pages

ISBN-10 194367907X

ISBN-13 9781943679072

2018

$18.00

# new books

Title One, No One, and One Hundred Thousand

Author Luigi Pirandello

Translated by William Weaver

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Book Stories, Archive O-P, Archive O-P, Luigi Pirandello, Pirandello, Luigi, Pirandello, Luigi, Samuel Beckett, Thomas Bernhard, Vladimir Nabokov

De meiskens uit de taveernen

De meiskens uit de taveernen,

Zij hebben een malsen schoot.

Zij zien er de jongens geerne.

Zij baren haar kindren dood.

Zij dragen van vurige zijde

een keursken dat spant en splijt.

We ontwaken aan haar zijde

met den houten mond van de spijt.

De ronde zee waar wij zwalken,

die eindeloos wenkt en geeuwt,

en ons doet van begeren balken,

en ons verre vrouwe verweêwt:

wij ankren in de taveernen

waar geniepig een rust ons smijt.

Daar wachten ons rood de deernen.

Daar raken wij ‘t leven kwijt.

Karel van de Woestijne

(1878 – 1929)

De meiskens uit de taveernen

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive W-X, Archive W-X, Woestijne, Karel van de

My Life had stood –

a Loaded Gun

My Life had stood – a Loaded Gun –

In Corners – till a Day

The Owner passed – identified –

And carried Me away –

And now We roam in Sovreign Woods –

And now We hunt the Doe –

And every time I speak for Him

The Mountains straight reply –

And do I smile, such cordial light

Opon the Valley glow –

It is as a Vesuvian face

Had let it’s pleasure through –

And when at Night – Our good Day done –

I guard My Master’s Head –

’Tis better than the Eider Duck’s

Deep Pillow – to have shared –

To foe of His – I’m deadly foe –

None stir the second time –

On whom I lay a Yellow Eye –

Or an emphatic Thumb –

Though I than He – may longer live

He longer must – than I –

For I have but the power to kill,

Without – the power to die –

Emily Dickinson

(1830-1886)

My Life had stood – a Loaded Gun

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive C-D, Dickinson, Emily

My Soul Is Dark

My soul is dark – Oh! quickly string

The harp I yet can brook to hear;

And let thy gentle fingers fling

Its melting murmurs o’er mine ear.

If in this heart a hope be dear,

That sound shall charm it forth again:

If in these eyes there lurk a tear,

‘Twill flow, and cease to burn my brain.

But bid the strain be wild and deep,

Nor let thy notes of joy be first:

I tell thee, minstrel, I must weep,

Or else this heavy heart will burst;

For it hath been by sorrow nursed,

And ached in sleepless silence, long;

And now ’tis doomed to know the worst,

And break at once – or yield to song.

George Gordon Byron

(1788 – 1824)

My Soul Is Dark

(Poem)

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Archive A-B, Byron, Lord

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature