Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

The Sleeper

At midnight, in the month of June,

I stand beneath the mystic moon.

An opiate vapor, dewy, dim,

Exhales from out her golden rim,

And softly dripping, drop by drop,

Upon the quiet mountain top,

Steals drowsily and musically

Into the universal valley.

The rosemary nods upon the grave;

The lily lolls upon the wave;

Wrapping the fog about its breast,

The ruin moulders into rest;

Looking like Lethe, see! the lake

A conscious slumber seems to take,

And would not, for the world, awake.

All Beauty sleeps!—and lo! where lies

Irene, with her Destinies!

Oh, lady bright! can it be right—

This window open to the night?

The wanton airs, from the tree-top,

Laughingly through the lattice drop—

The bodiless airs, a wizard rout,

Flit through thy chamber in and out,

And wave the curtain canopy

So fitfully—so fearfully—

Above the closed and fringéd lid

’Neath which thy slumb’ring soul lies hid,

That, o’er the floor and down the wall,

Like ghosts the shadows rise and fall!

Oh, lady dear, hast thou no fear?

Why and what art thou dreaming here?

Sure thou art come o’er far-off seas,

A wonder to these garden trees!

Strange is thy pallor! strange thy dress!

Strange, above all, thy length of tress,

And this all solemn silentness!

The lady sleeps! Oh, may her sleep,

Which is enduring, so be deep!

Heaven have her in its sacred keep!

This chamber changed for one more holy,

This bed for one more melancholy,

I pray to God that she may lie

Forever with unopened eye,

While the pale sheeted ghosts go by!

My love, she sleeps! Oh, may her sleep,

As it is lasting, so be deep!

Soft may the worms about her creep!

Far in the forest, dim and old,

For her may some tall vault unfold—

Some vault that oft hath flung its black

And wingéd pannels fluttering back,

Triumphant, o’er the crested palls

Of her grand family funerals—

Some sepulchre, remote, alone,

Against whose portals she hath thrown,

In childhood, many an idle stone—

Some tomb from out whose sounding door

She ne’er shall force an echo more,

Thrilling to think, poor child of sin!

It was the dead who groaned within.

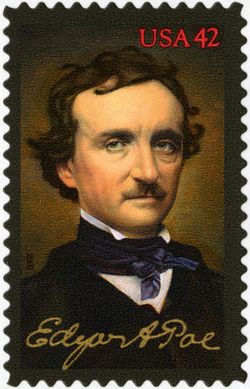

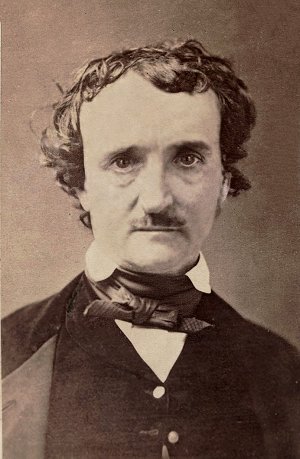

Edgar Allan Poe

(1809 – 1849)

The Sleeper

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Archive Tombeau de la jeunesse, Archive O-P, Archive O-P, Edgar Allan Poe, Poe, Edgar Allan, Poe, Edgar Allan, Tales of Mystery & Imagination

An indispensable anthology of brilliant hard-to-find writings by Poe on poetry, the imagination, humor, and the sublime which adds a new dimension to his stature as a speculative thinker and philosopher. Essays (in translation) by Charles Baudelaire, Stéphane Mallarmé, Paul Valéry, & André Breton shed light on Poe’s relevance within European literary tradition.

These are the arcana of Edgar Allan Poe: writings on wit, humor, dreams, drunkenness, genius, madness, and apocalypse. Here is the mind of Poe at its most colorful, its most incisive, and its most exceptional.

Edgar Allan Poe’s dark, melodic poems and tales of terror and detection are known to readers everywhere, but few are familiar with his cogent literary criticism, or his speculative thinking in science, psychology or philosophy. This book is an attempt to present his lesser known, out of print, or hard to find writings in a single volume, with emphasis on the theoretical and esoteric. The second part, “The Friend View,” includes seminal essays by Poe’s famous admirers in France, clarifying his international literary importance.

Edgar Allan Poe’s dark, melodic poems and tales of terror and detection are known to readers everywhere, but few are familiar with his cogent literary criticism, or his speculative thinking in science, psychology or philosophy. This book is an attempt to present his lesser known, out of print, or hard to find writings in a single volume, with emphasis on the theoretical and esoteric. The second part, “The Friend View,” includes seminal essays by Poe’s famous admirers in France, clarifying his international literary importance.

America has never seen such a personage as Edgar Allan Poe. He is a figure who appears once an epoch, before passing into myth. American critics from Henry James to T. S. Eliot have disparaged and attempted to explain away his influence to no end, save to perpetuate his fame. Even the disdainful Eliot once conceded, “and yet one cannot be sure that one’s own writing has not been influence by Poe.”

Edgar Allan Poe (1809-1849), born in Boston, Massachusetts, was an American poet, writer, editor, and literary critic. He is well known for his haunting poetry and mysterious short stories. Regarded as being a central figure of Romanticism, he is also considered the inventor of detective fiction and the growing science fiction genre. Some of his most famous works include poems such as The Raven, Annabel Lee, and A Dream Within a Dream; tales such as The Cask of Amontillado, The Masque of Red Death, and The Tell-Tale Heart.

Title: The Unknown Poe

Subtitle: An Anthology of Fugitive Writings

Author: Edgar Allan Poe

Edited by Raymond Foye

Publisher: City Lights Publishers

Format: Paperback

124 pages

1980

ISBN-10 0872861104

ISBN-13 9780872861107

List Price $11.95

# American writers

Edgar Allan Poe

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book Lovers, - Book Stories, Archive O-P, Archive O-P, Art & Literature News, Edgar Allan Poe, Poe, Edgar Allan, Poe, Edgar Allan, Tales of Mystery & Imagination

Poe’s cottage at Fordham

Here lived the soul enchanted

By melody of song;

Here dwelt the spirit haunted

By a demoniac throng;

Here sang the lips elated;

Here grief and death were sated;

Here loved and here unmated

Was he, so frail, so strong.

Here wintry winds and cheerless

The dying firelight blew,

While he whose song was peerless

Dreamed the drear midnight through,

And from dull embers chilling

Crept shadows darkly filling

The silent place, and thrilling

His fancy as they grew.

Here with brows bared to heaven,

In starry night he stood,

With the lost star of seven

Feeling sad brotherhood.

Here in the sobbing showers

Of dark autumnal hours

He heard suspected powers

Shriek through the stormy wood.

From visions of Apollo

And of Astarte’s bliss,

He gazed into the hollow

And hopeless vale of Dis,

And though earth were surrounded

By heaven, it still was mounded

With graves. His soul had sounded

The dolorous abyss.

Poor, mad, but not defiant,

He touched at heaven and hell.

Fate found a rare soul pliant

And wrung her changes well.

Alternately his lyre,

Stranded with strings of fire,

Led earth’s most happy choir,

Or flashed with Israfel.

No singer of old story

Luting accustomed lays,

No harper for new glory,

No mendicant for praise,

He struck high chords and splendid,

Wherein were finely blended

Tones that unfinished ended

With his unfinished days.

Here through this lonely portal,

Made sacred by his name,

Unheralded immortal

The mortal went and came.

And fate that then denied him,

And envy that decried him,

And malice that belied him,

Here cenotaphed his fame.

John Henry Boner

(1845-1903)

poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Edgar Allan Poe, Poe, Edgar Allan

Edgar Allan Poe

Edgar Allan Poe

The Cask of Amontillado

The thousand injuries of Fortunato I had borne as I best could, but when he ventured upon insult I vowed revenge. You, who so well know the nature of my soul, will not suppose, however, that gave utterance to a threat. At length I would be avenged; this was a point definitely, settled but the very definitiveness with which it was resolved precluded the idea of risk. I must not only punish but punish with impunity. A wrong is unredressed when retribution overtakes its redresser. It is equally unredressed when the avenger fails to make himself felt as such to him who has done the wrong.

It must be understood that neither by word nor deed had I given Fortunato cause to doubt my good will. I continued, as was my in to smile in his face, and he did not perceive that my to smile now was at the thought of his immolation.

He had a weak point this Fortunato although in other regards he was a man to be respected and even feared. He prided himself on his connoisseurship in wine. Few Italians have the true virtuoso spirit. For the most part their enthusiasm is adopted to suit the time and opportunity, to practise imposture upon the British and Austrian millionaires. In painting and gemmary, Fortunato, like his countrymen, was a quack, but in the matter of old wines he was sincere. In this respect I did not differ from him materially; I was skilful in the Italian vintages myself, and bought largely whenever I could.

It was about dusk, one evening during the supreme madness of the carnival season, that I encountered my friend. He accosted me with excessive warmth, for he had been drinking much. The man wore motley. He had on a tight-fitting parti-striped dress, and his head was surmounted by the conical cap and bells. I was so pleased to see him that I thought I should never have done wringing his hand.

I said to him “My dear Fortunato, you are luckily met. How remarkably well you are looking to-day. But I have received a pipe of what passes for Amontillado, and I have my doubts.”

“How?” said he. “Amontillado, A pipe? Impossible! And in the middle of the carnival!”

“I have my doubts,” I replied; “and I was silly enough to pay the full Amontillado price without consulting you in the matter. You were not to be found, and I was fearful of losing a bargain.”

“Amontillado!”

“I have my doubts.”

“Amontillado!”

“And I must satisfy them.”

“Amontillado!”

“As you are engaged, I am on my way to Luchresi. If any one has a critical turn it is he. He will tell me ”

“Luchresi cannot tell Amontillado from Sherry.”

“And yet some fools will have it that his taste is a match for your own.

“Come, let us go.”

“Whither?”

“To your vaults.”

“My friend, no; I will not impose upon your good nature. I perceive you have an engagement. Luchresi”

“I have no engagement; come.”

“My friend, no. It is not the engagement, but the severe cold with which I perceive you are afflicted. The vaults are insufferably damp. They are encrusted with nitre.”

“Let us go, nevertheless. The cold is merely nothing. Amontillado! You have been imposed upon. And as for Luchresi, he cannot distinguish Sherry from Amontillado.”

Thus speaking, Fortunato possessed himself of my arm; and putting on a mask of black silk and drawing a roquelaire closely about my person, I suffered him to hurry me to my palazzo.

There were no attendants at home; they had absconded to make merry in honour of the time. I had told them that I should not return until the morning, and had given them explicit orders not to stir from the house. These orders were sufficient, I well knew, to insure their immediate disappearance, one and all, as soon as my back was turned.

I took from their sconces two flambeaux, and giving one to Fortunato, bowed him through several suites of rooms to the archway that led into the vaults. I passed down a long and winding staircase, requesting him to be cautious as he followed. We came at length to the foot of the descent, and stood together upon the damp ground of the catacombs of the Montresors.

The gait of my friend was unsteady, and the bells upon his cap jingled as he strode.

“The pipe,” he said.

“It is farther on,” said I; “but observe the white web-work which gleams from these cavern walls.”

He turned towards me, and looked into my eves with two filmy orbs that distilled the rheum of intoxication.

“Nitre?” he asked, at length.

“Nitre,” I replied. “How long have you had that cough?”

“Ugh! ugh! ugh! ugh! ugh! ugh! ugh! ugh! ugh! ugh! ugh! ugh! ugh! ugh! ugh!”

My poor friend found it impossible to reply for many minutes.

“It is nothing,” he said, at last.

“Come,” I said, with decision, “we will go back; your health is precious. You are rich, respected, admired, beloved; you are happy, as once I was. You are a man to be missed. For me it is no matter. We will go back; you will be ill, and I cannot be responsible. Besides, there is Luchresi ”

“Enough,” he said; “the cough’s a mere nothing; it will not kill me. I shall not die of a cough.”

“True true,” I replied; “and, indeed, I had no intention of alarming you unnecessarily but you should use all proper caution. A draught of this Medoc will defend us from the damps.

Here I knocked off the neck of a bottle which I drew from a long row of its fellows that lay upon the mould.

“Drink,” I said, presenting him the wine.

He raised it to his lips with a leer. He paused and nodded to me familiarly, while his bells jingled.

“I drink,” he said, “to the buried that repose around us.”

“And I to your long life.”

He again took my arm, and we proceeded.

“These vaults,” he said, “are extensive.”

“The Montresors,” I replied, “were a great and numerous family.”

“I forget your arms.”

“A huge human foot d’or, in a field azure; the foot crushes a serpent rampant whose fangs are imbedded in the heel.”

“And the motto?”

“Nemo me impune lacessit.”

“Good!” he said.

The wine sparkled in his eyes and the bells jingled. My own fancy grew warm with the Medoc. We had passed through long walls of piled skeletons, with casks and puncheons intermingling, into the inmost recesses of the catacombs. I paused again, and this time I made bold to seize Fortunato by an arm above the elbow.

“The nitre!” I said; “see, it increases. It hangs like moss upon the vaults. We are below the river’s bed. The drops of moisture trickle among the bones. Come, we will go back ere it is too late. Your cough ”

“It is nothing,” he said; “let us go on. But first, another draught of the Medoc.” I broke and reached him a flagon of De Grave. He emptied it at a breath. His eyes flashed with a fierce light. He laughed and threw the bottle upwards with a gesticulation I did not understand. I looked at him in surprise. He repeated the movement a grotesque one.

“You do not comprehend?” he said.

“Not I,” I replied.

“Then you are not of the brotherhood.”

“How?”

“You are not of the masons.”

“Yes, yes,” I said; “yes, yes.”

“You? Impossible! A mason?”

“A mason,” I replied.

“A sign,” he said, “a sign.”

“It is this,” I answered, producing from beneath the

folds of my roquelaire a trowel.

“You jest,” he exclaimed, recoiling a few paces.

“But let us proceed to the Amontillado.”

“Be it so,” I said, replacing the tool beneath the cloak and again offering him my arm. He leaned upon it heavily. We continued our route in search of the Amontillado. We passed through a range of low arches, descended, passed on, and descending again, arrived at a deep crypt, in which the foulness of the air caused our flambeaux rather to glow than flame.

At the most remote end of the crypt there appeared another less spacious. Its walls had been lined with human remains, piled to the vault overhead, in the fashion of the great catacombs of Paris. Three sides of this interior crypt were still ornamented in this manner. From the fourth side the bones had been thrown down, and lay promiscuously upon the earth, forming at one point a mound of some size. Within the wall thus exposed by the displacing of the bones, we perceived a still interior crypt or recess, in depth about four feet, in width three, in height six or seven. It seemed to have been constructed for no especial use within itself, but formed merely the interval between two of the colossal supports of the roof of the catacombs, and was backed by one of their circumscribing walls of solid granite.

It was in vain that Fortunato, uplifting his dull torch, endeavoured to pry into the depth of the recess. Its termination the feeble light did not enable us to see.

“Proceed,” I said; “herein is the Amontillado. As for Luchresi ”

“He is an ignoramus,” interrupted my friend, as he stepped unsteadily forward, while I followed immediately at his heels. In niche, and finding an instant he had reached the extremity of the niche, and finding his progress arrested by the rock, stood stupidly bewildered. A moment more and I had fettered him to the granite. In its surface were two iron staples, distant from each other about two feet, horizontally. From one of these depended a short chain, from the other a padlock. Throwing the links about his waist, it was but the work of a few seconds to secure it. He was too much astounded to resist. Withdrawing the key I stepped back from the recess.

“Pass your hand,” I said, “over the wall; you cannot help feeling the nitre. Indeed, it is very damp. Once more let me implore you to return. No? Then I must positively leave you. But I must first render you all the little attentions in my power.”

“The Amontillado!” ejaculated my friend, not yet recovered from his astonishment.

“True,” I replied; “the Amontillado.”

As I said these words I busied myself among the pile of bones of which I have before spoken. Throwing them aside, I soon uncovered a quantity of building stone and mortar. With these materials and with the aid of my trowel, I began vigorously to wall up the entrance of the niche.

I had scarcely laid the first tier of the masonry when I discovered that the intoxication of Fortunato had in a great measure worn off. The earliest indication I had of this was a low moaning cry from the depth of the recess. It was not the cry of a drunken man. There was then a long and obstinate silence. I laid the second tier, and the third, and the fourth; and then I heard the furious vibrations of the chain. The noise lasted for several minutes, during which, that I might hearken to it with the more satisfaction, I ceased my labours and sat down upon the bones. When at last the clanking subsided, I resumed the trowel, and finished without interruption the fifth, the sixth, and the seventh tier. The wall was now nearly upon a level with my breast. I again paused, and holding the flambeaux over the mason-work, threw a few feeble rays upon the figure within.

A succession of loud and shrill screams, bursting suddenly from the throat of the chained form, seemed to thrust me violently back. For a brief moment I hesitated, I trembled. Unsheathing my rapier, I began to grope with it about the recess; but the thought of an instant reassured me. I placed my hand upon the solid fabric of the catacombs, and felt satisfied. I reapproached the wall; I replied to the yells of him who clamoured. I re-echoed, I aided, I surpassed them in volume and in strength.

I did this, and the clamourer grew still. It was now midnight, and my task was drawing to a close. I had completed the eighth, the ninth and the tenth tier. I had finished a portion of the last and the eleventh; there remained but a single stone to be fitted and plastered in. I struggled with its weight; I placed it partially in its destined position. But now there came from out the niche a low laugh that erected the hairs upon my head. It was succeeded by a sad voice, which I had difficulty in recognizing as that of the noble Fortunato.

The voice said–

“Ha! ha! ha! he! he! he! a very good joke, indeed an excellent jest. We will have many a rich laugh about it at the palazzo he! he! he! over our wine he! he! he!”

“The Amontillado!” I said.

“He! he! he! he! he! he! yes, the Amontillado. But is it not getting late? Will not they be awaiting us at the palazzo, the Lady Fortunato and the rest? Let us be gone.”

“Yes,” I said, “let us be gone.”

“For the love of God, Montresor!”

“Yes,” I said, “for the love of God!”

But to these words I hearkened in vain for a reply.

I grew impatient. I called aloud

“Fortunato!”

No answer. I called again

“Fortunato!”

No answer still. I thrust a torch through the remaining aperture and let it fall within. There came forth in return only a jingling of the bells. My heart grew sick; it was the dampness of the catacombs that made it so. I hastened to make an end of my labour. I forced the last stone into its position; I plastered it up. Against the new masonry I re-erected the old rampart of bones. For the half of a century no mortal has disturbed them.

In pace requiescat!

Edgar Allan Poe (1809 – 1849)

The Cask of Amontillado

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Edgar Allan Poe, Poe, Edgar Allan, Poe, Edgar Allan, Tales of Mystery & Imagination

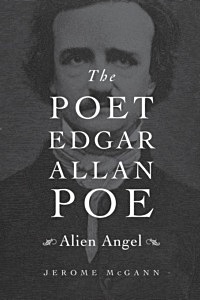

The poetry of Edgar Allan Poe has had a rough ride in America, as Emerson’s sneering quip about “The Jingle Man” testifies.

That these poems have never lacked a popular audience has been a persistent annoyance in academic and literary circles; that they attracted the admiration of innovative poetic masters in Europe and especially France—notably Baudelaire, Mallarmé, and Valéry—has been further cause for embarrassment. Jerome McGann offers a bold reassessment of Poe’s achievement, arguing that he belongs with Whitman and Dickinson as a foundational American poet and cultural presence.

That these poems have never lacked a popular audience has been a persistent annoyance in academic and literary circles; that they attracted the admiration of innovative poetic masters in Europe and especially France—notably Baudelaire, Mallarmé, and Valéry—has been further cause for embarrassment. Jerome McGann offers a bold reassessment of Poe’s achievement, arguing that he belongs with Whitman and Dickinson as a foundational American poet and cultural presence.

Not all American commentators have agreed with Emerson’s dim view of Poe’s verse. For McGann, a notable exception is William Carlos Williams, who said that the American poetic imagination made its first appearance in Poe’s work. The Poet Edgar Allan Poe explains what Williams and European admirers saw in Poe, how they understood his poetics, and why his poetry had such a decisive influence on Modern and Post-Modern art and writing. McGann contends that Poe was the first poet to demonstrate how the creative imagination could escape its inheritance of Romantic attitudes and conventions, and why an escape was desirable. The ethical and political significance of Poe’s work follows from what the poet takes as his great subject: the reader.

The Poet Edgar Allan Poe takes its own readers on a spirited tour through a wide range of Poe’s verse as well as the critical and theoretical writings in which he laid out his arresting ideas about poetry and poetics.

Jerome McGann is University Professor and John Stewart Bryan Professor of English at the University of Virginia.

“McGann succeeds in forcing us to rethink Poe’s poetry… Poe’s sound experiments, especially his strange variations on meter, deserve, as McGann shows by citing numerous rhythmic anomalies, to be taken seriously… In an age of predominantly, and purposely, flat and prosaic ‘free verse,’ mnemonic patterning is perhaps re-emerging as the emblem of poetic power. In this sense, Poe is once again Our Contemporary… In making the case for the close link between the poetry and the aesthetic theory, [McGann] succeeds admirably: Poe’s reputation as poete maudit belies the fact that here was a poet who knew exactly what he was doing.” — Marjorie Perloff, The Times Literary Supplement

Jerome McGann

The Poet Edgar Allan Poe

Alien Angel

256 pages

2014

Hardcover

Harvard University Press

€23.00

ISBN 9780674416666

literary criticism books

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book Stories, Archive O-P, Archive O-P, Art & Literature News, Edgar Allan Poe, Poe, Edgar Allan, Poe, Edgar Allan, Tales of Mystery & Imagination

Edgar Allan Poe

Edgar Allan Poe

The Tell Tale Heart

Trua! nervous, very, very dreadfully nervous I had been and am; but why Will you say that I am mad? The disease had sharpened my senses, not destroyed, not dulled them. Above all was the sense of hearing acute. I heard all things in the heaven and in the earth. I heard many things in hell. How then am I mad? Hearken! and observe how healthily, how calmly, I can tell you the whole story.

It is impossible to say how first the idea entered my brain, but, once conceived, it haunted me day and night. Object there was none. Passion there was none. I loved the old man. He had never wronged me. He had never given me insult. For his gold I had no desire. I think it was his eye! Yes, it was this! One of his eyes resembled that of a vulture a pale blue eye with a film over it. Whenever it fell upon me my blood ran cold, and so by degrees, very gradually, I made up my mind to take the life of the old man, and thus rid myself of the eye for ever.

Now this is the point. You fancy me mad. Madmen know nothing. But you should have seen me. You should have seen how wisely I proceeded with what caution with what foresight, with what dissimulation, I went to work! I was never kinder to the old man than during the whole week before I killed him. And every night about midnight I turned the latch of his door and opened it oh, so gently! And then, when I had made an opening sufficient for my head, I put in a dark lantern all closed, closed so that no light shone out, and then I thrust in my head. Oh, you would have laughed to see how cunningly I thrust it in! I moved it slowly, very, very slowly, so that I might not disturb the old man’s sleep. It took me an hour to place my whole head within the opening so far that I could see him as he lay upon his bed. Ha! would a madman have been so wise as this? And then when my head was well in the room I undid the lantern cautiously oh, so cautiously cautiously (for the hinges creaked), I undid it just so much that a single thin ray fell upon the vulture eye. And this I did for seven long nights, every night just at midnight, but I found the eye always closed, and so it was impossible to do the work, for it was not the old man who vexed me but his Evil Eye. And every morning, when the day broke, I went boldly into the chamber and spoke courageously to him, calling him by name in a hearty tone, and inquiring how he had passed the night. So you see he would have been a very profound old man, indeed , to suspect that every night, just at twelve, I looked in upon him while he slept.

Upon the eighth night I was more than usually cautious in opening the door. A watch’s minute hand moves more quickly than did mine. Never before that night had I felt the extent of my own powers, of my sagacity. I could scarcely contain my feelings of triumph. To think that there I was opening the door little by little, and he not even to dream of my secret deeds or thoughts. I fairly chuckled at the idea, and perhaps he heard me, for he moved on the bed suddenly as if startled. Now you may think that I drew back — but no. His room was as black as pitch with the thick darkness (for the shutters were close fastened through fear of robbers), and so I knew that he could not see the opening of the door, and I kept pushing it on steadily, steadily.

I had my head in, and was about to open the lantern, when my thumb slipped upon the tin fastening , and the old man sprang up in the bed, crying out, “Who’s there?”

I kept quite still and said nothing. For a whole hour I did not move a muscle, and in the meantime I did not hear him lie down. He was still sitting up in the bed, listening; just as I have done night after night hearkening to the death watches in the wall.

Presently, I heard a slight groan, and I knew it was the groan of mortal terror. It was not a groan of pain or of grief — oh, no! It was the low stifled sound that arises from the bottom of the soul when overcharged with awe. I knew the sound well. Many a night, just at midnight, when all the world slept, it has welled up from my own bosom, deepening, with its dreadful echo, the terrors that distracted me. I say I knew it well. I knew what the old man felt, and pitied him although I chuckled at heart. I knew that he had been lying awake ever since the first slight noise when he had turned in the bed. His fears had been ever since growing upon him. He had been trying to fancy them causeless, but could not. He had been saying to himself, “It is nothing but the wind in the chimney, it is only a mouse crossing the floor,” or, “It is merely a cricket which has made a single chirp.” Yes he has been trying to comfort himself with these suppositions ; but he had found all in vain. All in vain, because Death in approaching him had stalked with his black shadow before him and enveloped the victim. And it was the mournful influence of the unperceived shadow that caused him to feel, although he neither saw nor heard, to feel the presence of my head within the room.

When I had waited a long time very patiently without hearing him lie down, I resolved to open a little a very, very little crevice in the lantern. So I opened it you cannot imagine how stealthily, stealthily until at length a single dim ray like the thread of the spider shot out from the crevice and fell upon the vulture eye.

It was open, wide, wide open, and I grew furious as I gazed upon it. I saw it with perfect distinctness all a dull blue with a hideous veil over it that chilled the very marrow in my bones, but I could see nothing else of the old man’s face or person, for I had directed the ray as if by instinct precisely upon the damned spot.

And now have I not told you that what you mistake for madness is but over-acuteness of the senses? now, I say, there came to my ears a low, dull, quick sound, such as a watch makes when enveloped in cotton. I knew that sound well too. It was the beating of the old man’s heart. It increased my fury as the beating of a drum stimulates the soldier into courage.

But even yet I refrained and kept still. I scarcely breathed. I held the lantern motionless. I tried how steadily I could maintain the ray upon the eye. Meantime the hellish tattoo of the heart increased. It grew quicker and quicker, and louder and louder, every instant. The old man’s terror must have been extreme! It grew louder, I say, louder every moment! do you mark me well? I have told you that I am nervous: so I am. And now at the dead hour of the night, amid the dreadful silence of that old house, so strange a noise as this excited me to uncontrollable terror. Yet, for some minutes longer I refrained and stood still. But the beating grew louder, louder! I thought the heart must burst. And now a new anxiety seized me the sound would be heard by a neighbour! The old man’s hour had come! With a loud yell, I threw open the lantern and leaped into the room. He shrieked once once only. In an instant I dragged him to the floor, and pulled the heavy bed over him. I then smiled gaily, to find the deed so far done. But for many minutes the heart beat on with a muffled sound. This, however, did not vex me; it would not be heard through the wall. At length it ceased. The old man was dead. I removed the bed and examined the corpse. Yes, he was stone, stone dead. I placed my hand upon the heart and held it there many minutes. There was no pulsation. He was stone dead. His eye would trouble me no more.

If still you think me mad, you will think so no longer when I describe the wise precautions I took for the concealment of the body. The night waned, and I worked hastily, but in silence.

I took up three planks from the flooring of the chamber, and deposited all between the scantlings. I then replaced the boards so cleverly so cunningly, that no human eye not even his could have detected anything wrong. There was nothing to wash out no stain of any kind no blood-spot whatever. I had been too wary for that.

When I had made an end of these labours, it was four o’clock still dark as midnight. As the bell sounded the hour, there came a knocking at the street door. I went down to open it with a light heart, for what had I now to fear? There entered three men, who introduced themselves, with perfect suavity, as officers of the police. A shriek had been heard by a neighbour during the night; suspicion of foul play had been aroused; information had been lodged at the police office, and they (the officers) had been deputed to search the premises.

I smiled, for what had I to fear? I bade the gentlemen welcome. The shriek, I said, was my own in a dream. The old man, I mentioned, was absent in the country. I took my visitors all over the house. I bade them search search well. I led them, at length, to his chamber. I showed them his treasures, secure, undisturbed. In the enthusiasm of my confidence, I brought chairs into the room, and desired them here to rest from their fatigues, while I myself, in the wild audacity of my perfect triumph, placed my own seat upon the very spot beneath which reposed the corpse of the victim.

The officers were satisfied. My manner had convinced them. I was singularly at ease. They sat and while I answered cheerily, they chatted of familiar things. But, ere long, I felt myself getting pale and wished them gone. My head ached, and I fancied a ringing in my ears; but still they sat, and still chatted. The ringing became more distinct : I talked more freely to get rid of the feeling: but it continued and gained definitiveness until, at length, I found that the noise was not within my ears.

No doubt I now grew very pale; but I talked more fluently, and with a heightened voice. Yet the sound increased and what could I do? It was a low dull, quick sound much such a sound as a watch makes when enveloped in cotton. I gasped for breath, and yet the officers heard it not. I talked more quickly, more vehemently but the noise steadily increased. I arose and argued about trifles, in a high key and with violent gesticulations; but the noise steadily increased. Why would they not be gone? I paced the floor to and fro with heavy strides, as if excited to fury by the observations of the men, but the noise steadily increased. O God! what could I do? I foamed I raved I swore! I swung the chair upon which I had been sitting, and grated it upon the boards, but the noise arose over all and continually increased. It grew louder louder louder! And still the men chatted pleasantly , and smiled. Was it possible they heard not? Almighty God! no, no? They heard! they suspected! they knew! they were making a mockery of my horror! this I thought, and this I think. But anything was better than this agony! Anything was more tolerable than this derision! I could bear those hypocritical smiles no longer! I felt that I must scream or die! and now again hark! louder! louder! louder! Louder!

“Villains!” I shrieked, “dissemble no more! I admit the deed! tear up the planks! Here, here! It is the beating of his hideous heart!”

Edgar Allan Poe (1809 – 1849)

The Tell Tale Heart

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Edgar Allan Poe, Poe, Edgar Allan, Poe, Edgar Allan

Edgar Allan Poe

The City in the Sea

Lo! Death has reared himself a throne

In a strange city lying alone

Far down within the dim West,

Where the good and the bad and the worst and the best

Have gone to their eternal rest.

There shrines and palaces and towers

(Time-eaten towers that tremble not!)

Resemble nothing that is ours.

Around, by lifting winds forgot,

Resignedly beneath the sky

The melancholy waters lie.

No rays from the holy heaven come down

On the long night-time of that town;

But light from out the lurid sea

Streams up the turrets silently

Gleams up the pinnacles far and free

Up domes up spires up kingly halls

Up fanes up Babylon-like walls

Up shadowy long-forgotten bowers

Of sculptured ivy and stone flowers

Up many and many a marvelous shrine

Whose wreathèd friezes intertwine

The viol, the violet, and the vine.

Resignedly beneath the sky

The melancholy waters lie.

So blend the turrets and shadows there

That all seem pendulous in air,

While from a proud tower in the town

Death looks gigantically down.

There open fanes and gaping graves

Yawn level with the luminous waves;

But not the riches there that lie

In each idol’s diamond eye

Not the gaily-jeweled dead

Tempt the waters from their bed;

For no ripples curl, alas!

Among that wilderness of glass

No swellings tell that winds may be

Upon some far-off happier sea

No heavings hint that winds have been

On seas less hideously serene.

But lo, a stir is in the air!

The wave there is a movement there!

As if the towers had thrust aside,

In slightly sinking, the dull tide

As if their tops had feebly given

A void within the filmy Heaven.

The waves have now a redder glow

The hours are breathing faint and low

And when, amid no earthly moans,

Down, down that town shall settle hence,

Hell, rising from a thousand thrones,

Shall do it reverence.

Edgar Allan Poe (1809 – 1849)

The City in the Sea

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Edgar Allan Poe, Poe, Edgar Allan, Poe, Edgar Allan

Lezing en voordracht van The Raven van E.A. Poe in Museum Meermanno / Huis van het boek, Den Haag

Op zaterdag 30 augustus spreekt Johan Vandendriessche over ‘The Raven’ van Edgar Allan Poe en draagt hij het gedicht voor.

Op zaterdag 30 augustus spreekt Johan Vandendriessche over ‘The Raven’ van Edgar Allan Poe en draagt hij het gedicht voor.

‘The Raven’ van Edgar Allan Poe (1809 – 1849) is één der meest beklijvende gedichten uit de Amerikaanse literatuur. Wat zit er achter de symboliek? Hoe breng je dit gedicht uit 1845 vandaag, in het Nederlands, met respect voor de originele versie? Wat doet dit gedicht met een mens, die er lang mee bezig is? En welke dualiteit spookte door het brein van Poe? Johan Vandendriessche (Bibliotheek Permeke – Antwerpen) duikt samen met de raaf in een tolvlucht naar de kern van het gedicht.

Na de lezing en voordracht van het gedicht is er gelegenheid voor vragen. De lezing wordt afgesloten met koffie en thee. Tevens kunt u de tentoonstelling ‘Vogels. Duizenden vogels in honderden boeken’ bezoeken en de nieuwe aanwinsten van het museum met onder meer een geïllustreerde uitgave van ‘The Raven’ door de Cheloniidae Press met etsen en houtgravuren van kunstenaar Alan James Robinson.

De lezing is van 14.00 tot 15.00 uur, waarna koffie en thee wordt geserveerd. (Inloop vanaf 13.30)

Kosten en aanmelden: de lezing kost € 5,- exclusief museumentree. Zie voor meer informatie over lezing, tentoonstelling en andere activiteiten: www.meermanno.nl

Huis van het boek

Museum Meermanno

Prinsessegracht 30

2514 AP Den Haag

T 070 34 62 700

info@meermanno.nl

www.meermanno.nl

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive O-P, Art & Literature News, Poe, Edgar Allan, Tales of Mystery & Imagination

Photo by David Shankbone

In memory of Lucy Gordon

To One in Paradise

by Edgar Allan Poe

Thou wast that all to me, love,

For which my soul did pine—

A green isle in the sea, love,

A fountain and a shrine,

All wreathed with fairy fruits and flowers,

And all the flowers were mine.

Ah, dream too bright to last!

Ah, starry Hope! that didst arise

But to be overcast!

A voice from out the Future cries,

“On! on!”—but o’er the Past

(Dim gulf!) my spirit hovering lies

Mute, motionless, aghast!

For, alas! alas! with me

The light of Life is o’er!

No more—no more—no more—

(Such language holds the solemn sea

To the sands upon the shore)

Shall bloom the thunder-blasted tree,

Or the stricken eagle soar!

And all my days are trances,

And all my nightly dreams

Are where thy grey eye glances,

And where thy footstep gleams—

In what ethereal dances,

By what eternal streams.

20 May 2014: In memory of Lucy Gordon (22 May 1980 – 20 May 2009)

Photo Lucy gordon by David Shankbone: Lucy Gordon at the 2007 premiere of Spider-Man 3

(David Shankbone: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license), 2007)

Tombeau de la Jeunesse – fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: In Memoriam, Lucy Gordon, Poe, Edgar Allan

Edgar Allan Poe

(1809 – 1849)

Evening Star

‘Twas noontide of summer,

And mid-time of night;

And stars, in their orbits,

Shone pale, thro’ the light

Of the brighter, cold moon,

‘Mid planets her slaves,

Herself in the Heavens,

Her beam on the waves.

I gazed awhile

On her cold smile;

Too cold- too cold for me-

There pass’d, as a shroud,

A fleecy cloud,

And I turned away to thee,

Proud Evening Star,

In thy glory afar,

And dearer thy beam shall be;

For joy to my heart

Is the proud part

Thou bearest in Heaven at night,

And more I admire

Thy distant fire,

Than that colder, lowly light.

Edgar Allan Poe poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive O-P, Poe, Edgar Allan

Edgar Allan Poe

(1809 – 1849)

Evening Star

‘Twas noontide of summer,

And mid-time of night;

And stars, in their orbits,

Shone pale, thro’ the light

Of the brighter, cold moon,

‘Mid planets her slaves,

Herself in the Heavens,

Her beam on the waves.

I gazed awhile

On her cold smile;

Too cold- too cold for me-

There pass’d, as a shroud,

A fleecy cloud,

And I turned away to thee,

Proud Evening Star,

In thy glory afar,

And dearer thy beam shall be;

For joy to my heart

Is the proud part

Thou bearest in Heaven at night,

And more I admire

Thy distant fire,

Than that colder, lowly light.

Edgar Allan Poe poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive O-P, Poe, Edgar Allan

Edgar Allan Poe

(1809-1849)

Spirits Of The Dead

Thy soul shall find itself alone

‘Mid dark thoughts of the grey tomb-stone;

Not one, of all the crowd, to pry

Into thine hour of secrecy.

Be silent in that solitude,

Which is not loneliness- for then

The spirits of the dead, who stood

In life before thee, are again

In death around thee, and their will

Shall overshadow thee; be still.

The night, though clear, shall frown,

And the stars shall not look down

From their high thrones in the Heaven

With light like hope to mortals given,

But their red orbs, without beam,

To thy weariness shall seem

As a burning and a fever

Which would cling to thee for ever.

Now are thoughts thou shalt not banish,

Now are visions ne’er to vanish;

From thy spirit shall they pass

No more, like dew-drop from the grass.

The breeze, the breath of God, is still,

And the mist upon the hill

Shadowy, shadowy, yet unbroken,

Is a symbol and a token.

How it hangs upon the trees,

A mystery of mysteries!

Edgar Allan Poe poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive O-P, Poe, Edgar Allan

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature