Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

Der Kirchhof

Du stiller Ort, der grünt mit jungem Grase,

Da liegen Mann und Frau, und Kreuze stehn,

Wohin hinaus geleitet Freunde gehn,

Wo Fenster sind glänzend mit hellem Glase.

Wenn glänzt an dir des Himmels hohe Leuchte

Des Mittags, wann der Frühling dort oft weilt,

Wenn geistige Wolke dort, die graue, feuchte,

Wenn sanft der Tag vorbei mit Schönheit eilt!

Wie still ist′s nicht an jener grauen Mauer,

Wo drüber her ein Baum mit Früchten hängt;

Mit schwarzen tauigen, und Laub voll Trauer,

Die Früchte aber sind sehr schön gedrängt.

Dort in der Kirch ist eine dunkle Stille

Und der Altar ist auch in dieser Nacht geringe,

Noch sind darin einige schöne Dinge,

Im Sommer aber singt auf Feldern manche Grille.

Wenn einer dort Reden des Pfarrherrn hört,

Indes die Schar der Freunde steht daneben,

Die mit dem Toten sind, welch eignes Leben

Und welcher Geist, und fromm sein ungestört.

Friedrich Hölderlin

(1770 – 1843)

Der Kirchhof

Gedicht

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive G-H, Archive G-H, Hölderlin, Friedrich

Summer Songs

I

How thick the grass,

How green the shade–

All for love

And lovers made.

Wood-lilies white

As hidden lace–

Open your bodice,

That’s their place.

See how the sun-god

Overpowers

The summer lying

Deep in flowers;

With burning kisses

Of bright gold

Fills her young womb

With joy untold;

And all the world

Is lad and lass,

A blue sky

And a couch of grass.

Summer is here–

let us drain

It all! it may

Not come again.

II

How the leaves thicken

On the boughs,

And the birds make

Their lyric vows.

O the beating, breaking

Heart of things,

The pulse and passion–

How it sings.

How it burns and flames

And showers,

Lusts and laughs, flowers

And deflowers.

III

Summer came,

Rose on rose;

Leaf on leaf,

Summer goes.

Summer came,

Song on song;

O summer had

A golden tongue.

Summer goes,

Sigh on sigh;

Not a rose

Sees him die.

Richard Le Gallienne

(1866 – 1947)

Summer Songs

From: The lonely Dancer and other Poems, 1913

•fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: 4SEASONS#Summer, Archive G-H, Archive G-H, Gallienne, Richard Le

Rêve

Je rêve un fort splendide et calme, où la nature

S’endort entre la rive et le flot infini,

Près de palais portant des dômes d’or bruni,

Près des vaisseaux couvrant de drapeaux leur mâture.

Vers le large horizon où vont les matelots

Les cloches d’argent fin jettent leurs chants étranges.

L’enivrante senteur des vins et des oranges

Se mêle à la senteur enivrante des flots…

Une lente chanson monte vers les étoiles,

Douce comme un soupir, triste comme un adieu.

Sur l’horizon la lune ouvre son œil de feu

Et jette ses rayons parmi les lourdes voiles.

Brune à la lèvre rose et couverte de fards,

La fille, l’œil luisant comme une girandole,

Sur la hanche roulant ainsi qu’une gondole,

Hideusement s’en va sous les flots blafards.

Et moi, mélancolique amant de l’onde sombre,

Ami des grands vaisseaux noirs le silencieux,

J’erre dans la fraîcheur du vent délicieux

Qui fait trembler dans l’eau des lumières sans nombre.

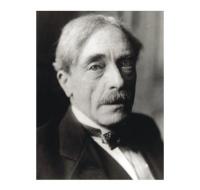

Paul Valéry

(1871-1945)

Rêve

Poème

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive U-V, Archive U-V, Valéry, Paul

The Little Vagabond

Dear mother, dear mother, the Church is cold;

But the Alehouse is healthy, and pleasant, and warm.

Besides, I can tell where I am used well;

The poor parsons with wind like a blown bladder swell.

But, if at the Church they would give us some ale,

And a pleasant fire our souls to regale,

We’d sing and we’d pray all the livelong day,

Nor ever once wish from the Church to stray.

Then the Parson might preach, and drink, and sing,

And we’d be as happy as birds in the spring;

And modest Dame Lurch, who is always at church,

Would not have bandy children, nor fasting, nor birch.

And God, like a father, rejoicing to see

His children as pleasant and happy as he,

Would have no more quarrel with the Devil or the barrel,

But kiss him, and give him both drink and apparel.

William Blake

(1757 – 1827)

The Little Vagabond

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Archive A-B, Blake, William, Tales of Mystery & Imagination

“Face in the Tomb

that Lies so Still”

Face in the tomb, that lies so still,

May I draw near,

And watch your sleep and love you,

Without word or tear.

You smile, your eyelids flicker;

Shall I tell

How the world goes that lost you?

Shall I tell?

Ah! love, lift not your eyelids;

‘Tis the same

Old story that we laughed at,–

Still the same.

We knew it, you and I,

We knew it all:

Still is the small the great,

The great the small;

Still the cold lie quenches

The flaming truth,

And still embattled age

Wars against youth.

Yet I believe still in the ever-living God

That fills your grave with perfume,

Writing your name in violets across the sod,

Shielding your holy face from hail and snow;

And, though the withered stay, the lovely go,

No transitory wrong or wrath of things

Shatters the faith–that each slow minute brings

That meadow nearer to us where your feet

Shall flicker near me like white butterflies–

That meadow where immortal lovers meet,

Gazing for ever in immortal eyes.

Richard Le Gallienne

(1866 – 1947)

“Face in the Tomb that Lies so Still”

From: The lonely Dancer and other Poems, 1913

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive G-H, Archive G-H, Galerie des Morts, Gallienne, Richard Le

A Book

There is no frigate like a book

To take us lands away,

Nor any coursers like a page

Of prancing poetry.

This traverse may the poorest take

Without oppress of toll;

How frugal is the chariot

That bears a human soul!

Emily Dickinson

(1830-1886)

A Book

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book Stories, Archive C-D, Archive C-D, Dickinson, Emily

“I said–I care not”

I said–I care not if I can

But look into her eyes again,

But lay my hand within her hand

Just once again.

Though all the world be filled with snow

And fire and cataclysmal storm,

I’ll cross it just to lay my head

Upon her bosom warm.

Ah! bosom made of April flowers,

Might I but bring this aching brain,

This foolish head, and lay it down

On April once again!

Richard Le Gallienne

(1866 – 1947)

“I said–I care not”

From: The lonely Dancer and other Poems, 1913

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive G-H, Archive G-H, Gallienne, Richard Le

The Grey Monk

“I die, I die!” the Mother said,

“My children die for lack of bread.

What more has the merciless Tyrant said?”

The Monk sat down on the stony bed.

The blood red ran from the Grey Monk’s side,

His hands and feet were wounded wide,

His body bent, his arms and knees

Like to the roots of ancient trees.

His eye was dry; no tear could flow:

A hollow groan first spoke his woe.

He trembled and shudder’d upon the bed;

At length with a feeble cry he said:

“When God commanded this hand to write

In the studious hours of deep midnight,

He told me the writing I wrote should prove

The bane of all that on Earth I lov’d.

My Brother starv’d between two walls,

His Children’s cry my soul appalls;

I mock’d at the rack and griding chain,

My bent body mocks their torturing pain.

Thy father drew his sword in the North,

With his thousands strong he marched forth;

Thy Brother has arm’d himself in steel

To avenge the wrongs thy Children feel.

But vain the Sword and vain the Bow,

They never can work War’s overthrow.

The Hermit’s prayer and the Widow’s tear

Alone can free the World from fear.

For a Tear is an intellectual thing,

And a Sigh is the sword of an Angel King,

And the bitter groan of the Martyr’s woe

Is an arrow from the Almighty’s bow.

The hand of Vengeance found the bed

To which the Purple Tyrant fled;

The iron hand crush’d the Tyrant’s head

And became a Tyrant in his stead.”

William Blake

(1757 – 1827)

The Grey Monk

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Archive A-B, Blake, William, Tales of Mystery & Imagination

Stichting Feest der Poëzie organiseert met Sociëteit “De Unie” Hilversum op donderdag 29 oktober 2020 in de serie Gooise dichters van het Feest der Poëzie een avond over Herman Gorter.

Herman Gorter, de dichter van ‘Mei’ (‘Een nieuwe lente en een nieuw geluid…’), woonde een aantal jaren aan de Nieuwe ‘s-Gravelandseweg 66 in Bussum, in een huis naar ontwerp van architect Berlage.

Voordrachtskunstenaar Simon Mulder en soundscape-artiesten Beggar Brahim (elektrische gitaar) en Jesse LaChiffre (klarinet) brengen nummers van de CD ‘Herman Gorter – Verzen 1890’, waarbij de gedichten uit de lyrische, experimentele, sensitivistische periode van classicus, dichter en socialist Herman Gorter, een unieke samenklank aangaan met Beggar Brahims klanklandschappen.

Klassiek muziekduo Marleen van Os en Daan van de Velde brengt bijzondere en nauwelijks uitgevoerde liederen op teksten van Gorter, bijgestaan door sopraan Heleen Oomen.

Stadsdichter Mieke van Zonneveld brengt de gedichten van Gorter die zij als motto’s in haar debuutbundel Leger gebruikte, en de daarbij behorende gedichten.

Verder bijzondere filmbeelden van Gorter van filminstituut Eye en de première van de videoclip ‘In de zwarte nacht’.

Sociëteit “De Unie” Hilversum

donderdag 29 oktober 2020

20:00 – 22:00 uur

s-Gravelandseweg 57

1217 EH Hilversum

Reserveringen worden verzorgd door ticketkantoor.nl

# Website Stichting Feest der Poëzie

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: # Music Archive, #Editors Choice Archiv, Archive G-H, Archive G-H, Art & Literature News, AUDIO, CINEMA, RADIO & TV, Feest der Poëzie, Gorter, Herman

Vue

Si la plage planche, si

L’ombre sur l’œil s’use et pleure

Si l’azur est larme, ainsi

Au sel des dents pure affleure

La vierge fumée ou l’air

Que berce en soi puis expire

Vers l’eau debout d’une mer

Assoupie en son empire

Celle qui sans les ouïr

Si la lèvre au vent remue

Se joue à évanouir

Mille mots vains où se mue

Sous l’humide éclair de dents

Le très doux feu du dedans.

Paul Valéry

(1871-1945)

Vue

Poème

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive U-V, Archive U-V, Valéry, Paul

To The Muses

Whether on Ida’s shady brow,

Or in the chambers of the East,

The chambers of the sun, that now

From ancient melody have ceas’d;

Whether in Heav’n ye wander fair,

Or the green corners of the earth,

Or the blue regions of the air,

Where the melodious winds have birth;

Whether on crystal rocks ye rove,

Beneath the bosom of the sea

Wand’ring in many a coral grove,

Fair Nine, forsaking Poetry!

How have you left the ancient love

That bards of old enjoy’d in you!

The languid strings do scarcely move!

The sound is forc’d, the notes are few!

William Blake

(1757 – 1827)

To The Muses

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Archive A-B, Blake, William, Tales of Mystery & Imagination

Hélène

Azur ! c’est moi… Je viens des grottes de la mort

Entendre l’onde se rompre aux degrés sonores,

Et je revois les galères dans les aurores

Ressusciter de l’ombre au fil des rames d’or.

Mes solitaires mains appellent les monarques

Dont la barbe de sel amusait mes doigts purs ;

Je pleurais. Ils chantaient leurs triomphes obscurs

Et les golfes enfuis aux poupes de leurs barques.

J’entends les conques profondes et les clairons

Militaires rythmer le vol des avirons ;

Le chant clair des rameurs enchaîne le tumulte,

Et les Dieux, à la proue héroïque exaltés

Dans leur sourire antique et que l’écume insulte,

Tendent vers moi leurs bras indulgents et sculptés.

Paul Valéry

(1871-1945)

Hélène

Poème

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive U-V, Archive U-V, Valéry, Paul

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature