Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

Tweedekkers boven de Meir

Mooie zondagmorgen zonder wetenschap:

hoe komt het dat de tijd me uitzweet

als escadrilles tweedekkers parmantig

boven de Meir brommen? Heeft geschiedenis

zich hier van spinrag ontdaan? Het wolkendek,

trapeze zonder vangnet, plots een stolp.

Oorlogsverklaringen. Menigte voor de Feldhernnhalle

juicht nieuw Europa toe. De lucht in hoeden.

Dan zie ik Otto Dix, sta ik weer op het verste punt

dat de Duitsers in ’16, mijn vaders geboortejaar,

bij de Somme wisten te bereiken en is

de stad bezet alsof Van Ostaijen hier nu nog woont.

‘s Nachts in bed beklemming als ik met d’Annunzio

jaag door het luchtruim, kogels om mijn oren fluiten

en ik van Triëst naar Fiume mee marcheer. De lakens

van me afgeslagen en daarmee de dromen: nachtelijk uitzicht

bewegende zichzelf. Willen genoeg.

Bert Bevers

uit In de buurt van de wereld, Uitgeverij Kleinood & Grootzeer, Bergen op Zoom, 2006

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Bevers, Bert

Eigen terrein

Gedichten 1998-2013

Dit mooi vormgegeven boek, dat onlangs van de persen rolde, bevat een ruime keuze uit de gedichten die Bert Bevers (o.a. medewerker van fleursdumal.nl magazine) het afgelopen anderhalve decennium schreef.

Dichter: Bert Bevers

www.bertbevers.com

Titel: Eigen terrein – Gedichten 1998-2013

Uitgeverij: Wel, Bergen op Zoom

Jaar van verschijning: 2013

Omvang: 144 p.

ISBN: 90 6230 098 7

Het boek kost € 20 (plus verzendkosten)

Bestellen kan via email: info@bertbevers

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Art & Literature News, Bevers, Bert

Martin Beversluis

Wetenschap

Ik stuur een lantaarnpaal de stroomrekening

swaffel tegen schrikdraad

en zet zangvogels vast wegens spionage

in meesmuilend doorluchtige taal vertel ik u

dat u een fout hebt gemaakt

en dat dat licht aan het eind van de tunnel

slechts resultaat is van het sterven van een cel

graag schroef ik voor uw ogen

het wonder uit elkaar

tot er wetenschap overblijft

daarna kweek ik een hamburger uit uw gestorven vlees

-met ui en een flinke klodder saus op een broodje van de hema-

aan mijn eeltkamertafel zal ik u met smaak eten.

Martin Beversluis poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Beversluis, Martin

De Toneelmakerij speelt De Storm van William Shakespeare

De succesvoorstelling van de Toneelmakerij & Firma Rieks Swarte is terug in het theater! De Storm is winnaar van de allereerste Z@PP Theaterprijs, werd geselecteerd voor het Nederlands Theater Festival 2011, is winnaar van een Zilveren Krekel en van de Wijnberg Scenografie Prijs 2011.

De oude tovenaar Prospero staart over het water. Ooit was hij de machtige hertog van Milaan, tot hij werd verstoten door zijn eigen broer Antonio. Nu heerst Prospero over een onherbergzaam eiland ver weg van stad en land. Hier leeft hij met zijn dochter Miranda, luchtgeest Ariël en zijn enige onderdaan, Calibaan het duivelskind. Tot op een dag het schip van zijn broer langs vaart. Een vreselijke storm steekt op in zijn hoofd. Vanuit het niets is de zee wild en woest, de lucht gitzwart. En het schip verdwijnt tussen huizenhoge golven. De opvarenden spoelen aan op een doodstil strand. Geen van hen weet dat zij overgeleverd zijn aan Prospero. Ook Antonio niet…

Wat volgt is een tocht vol wonderen en tovenarij over een magisch eiland waar niets is wat het lijkt. Een reis waarin Miranda voor het eerst de liefde ontdekt, de schipbreukelingen verward ronddolen en Prospero wraak neemt én vergeving schenkt.

tekst William Shakespeare bewerking Liesbeth Coltof, Rieks Swarte regie Liesbeth Coltof dramaturgie Annemarie Wenzel toneelbeeld Rieks Swarte ontwerp en uitvoering rekwisieten/poppen/maskers Jacqueline van Eeden, Rieks Swarte muziek Joost Belinfante kostuumontwerp Carly Everaert lichtontwerp Floriaan Ganzevoort – De Theatermachine spel Tjebbo Gerritsma, Peter de Graef, Rogier in ‘t Hout, Ferdi Janssen, Mira van der Lubbe, Lykele Muus, Chiem Vreeken

# Speellijst website De toneelmakerij

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Art & Literature News, Shakespeare, William, THEATRE

toneelgroep amsterdam

william shakespeare

romeinse tragedies

regisseur ivo van hove

van william shakespeare

duur 5:30

Na staande ovaties in o.a. New York, Londen, Wenen, Avignon, Wroclaw, Montreal, Quebec en Barcelona is Romeinse tragedies dit seizoen in Amsterdam en – voor het eerst – in het Australische Adelaide te zien. Romeinse tragedies is een zes uur durende non-stop gefilmde en uitgezonden liveshow waarin het publiek zich te midden van de 14 acteurs beweegt, kan eten en drinken op scène en in real time kan reageren (#romantragedies).

Romeinse tragedies staat op 18, 19, 21 en 22 dec 2013 in Amsterdam.

In Romeinse tragedies hebben Ivo Van Hove en vormgever Jan Versweyveld een unieke arena gecreëerd waarin Shakespeare meer dan ooit over onze tijd spreekt en waarin het publiek zich lijfelijk betrokken voelt bij het politieke spel in al zijn facetten. Die arena – een non-stop gefilmde en uitgezonden liveshow waarin de politici met elkaar in de clinch gaan, maar ook de achterkant van het politieke bedrijf wordt getoond in al zijn dubbelzinnigheid – daagt het publiek uit om ook letterlijk standpunt in te nemen: de toeschouwers bewegen zich tussen de spelers en achter de schermen, eten en drinken op scène en reflecteren via social media op de voorstelling in real time.

Chris Nietvelt werd voor haar rol als Cleopatra bekroond met de Theo d’Or 2008. Hans Kesting en Frieda Pittoors ontvingen nominaties voor respectievelijk de Louis d’Or en de Colombina. Romeinse tragedies werd voor het Nederlands Theater Festival geselecteerd en reist sindsdien de hele wereld over: van Wenen, Avignon, Antwerpen, Zürich, Wroclaw, Londen, Montreal, Quebec naar New York. In seizoen 13|14 in Amsterdam, Barcelona en het Australische Adelaide te zien.

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Art & Literature News, Shakespeare, William, THEATRE

MAISON DE LA POÉSIE PARIS:

Femmes de pouvoir et pouvoirs de femmes

Vendredi 20 décembre 2013 – 20H00

Océanerosemarie

Concert littéraire

On connaissait Oshen chanteuse (dernier album en date : « La pudeur », 2011) ; on la connaît à présent sous une autre identité : Océanerosemarie, auteur et interprète d’un spectacle irrésistible : La Lesbienne invisible qu’elle a joué longuement à Paris et en province. C’est à la fois Oshen et Océanerosemarie qui est l’invitée de la Maison de la Poésie. Le « féminisme comme moteur poétique » : telle sera la ligne de force de cette soirée.

Accompagnée de Christelle Lassort au violon et de Maëva Le Berre au violoncelle, Océanerosemarie fera entendre des voix féminines batailleuses de notre temps : Joy Sorman, Virginie Despentes, Leslie Kaplan, Jeanette Winterson ou encore Annie Ernaux ; mais également de grandes figures du passé telles que Grisélidis Réal ou Marina Tsvetaeva. Elle chantera, en miroir, des chansons de son propre répertoire.

# website maison de la poésie paris

Maison de la Poésie

Passage Molière

157, rue Saint-Martin – 75003 Paris

M° Rambuteau – RER Les Halles

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Art & Literature News, Maison de la Poésie, POETRY ARCHIVE, THEATRE

P.C. Hooft-prijs 2014 voor Willem Jan Otten

Het bestuur van de Stichting P.C. Hooft-prijs voor Letterkunde heeft maandag 9 december besloten de P.C. Hooft-prijs 2014 toe te kennen aan Willem Jan Otten (Amsterdam, 1951). Deze oeuvreprijs is dit jaar bestemd voor beschouwend proza en wordt uitgereikt op een feestelijke bijeenkomst in het Letterkundig Museum, op donderdag 22 mei 2014, 1 dag na de sterfdag van de naamgever van de prijs, de dichter P.C. Hooft (1581-1647), onze grootste renaissancedichter.

De P.C. Hooft-prijs 2014 voor het gehele oeuvre van Willem Jan Otten is toegekend op voordracht van een jury bestaande uit Désanne van Brederode, Elma Drayer, Annet Mooij, Jeroen van Kan en Paul Schnabel (voorzitter). Recente eerdere laureaten in het genre essay waren H.J.A. Hofland (2011), Abram de Swaan (2008) en Frédéric Bastet (2005). Aan de prijs is een bedrag verbonden van € 60.000.

Fragment uit het juryrapport: Willem Jan Otten kan gezien worden als een essayist pur sang. Hij is origineel en persoonlijk in de keuzen van zijn onderwerpen. Als lezer merk je hoe hij al schrijvend op zoek is naar een ook voor hem nog onbekende uitkomst van zijn denken.

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, Art & Literature News, Awards & Prizes, Otten, Willem Jan, The talk of the town

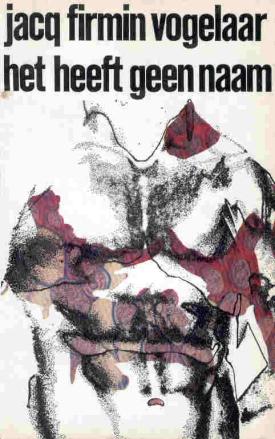

Schrijver Jacq Vogelaar overleden

Op maandag 9 december is de schrijver, essayist en criticus Jacq Vogelaar op 69-jarige leeftijd overleden. Jacq Vogelaar is het pseudoniem van de in 1944 in Tilburg geboren Frans Broers. Vogelaar kreeg in 2006 de Constantijn Huygensprijs voor zijn hele oeuvre.

De schrijver studeerde Nederlands en filosofie en debuteerde in 1965 als dichter. Daarna schreef hij als Jacq Firmin Vogelaar een aantal experimentele romans als Anatomie van een glasachtig lichaam (1966) en Raadsels van het rund (1978). Voor zijn roman De dood als meisje van acht (1991) kreeg hij de F. Bordewijkprijs.

In 2006 publiceerde Jacq Vogelaar zijn bundel: Over kampliteratuur, waaarin hij verslag doet van zijn zoektocht door de literatuur over de goelag-kampen in de Sovjet-Unie en de Duitse concentratie- en vernietigingskampen.

Jacq Vogelaar schreef vele jaren literatuurkritieken en essays voor De Groene Amsterdammer en voor het literatuurtijdschrift Raster.

Werken van Jacq Firmin Vogelaar

De komende en gaande man (1965)

Parterre, en van glas (1965)

Anatomie van een glasachtig lichaam (1966)

Vijand gevraagd (1967)

Gedaanteverandering of ‘n metaforiese muizeval (1968)

Het heeft geen naam (1968)

Kaleidiafragmenten (1970)

Kunst als kritiek (1972)

Konfrontaties (1974)

‘Ik in Kapitaal. Voorstudie van Pp.’, in Het mes in het beeld (1976)

Het mes in het beeld (1976)

Raadsels van het rund (1978)

Alle vlees (1980)

Oriëntaties (1983)

Het geheim van de bolhoeden (1986)

Terugschrijven (1987)

Terugschrijven (1988)

Verdwijningen (1988)

De dood als meisje van acht (1991)

Speelruimte (1991)

De dood als meisje van acht (1992)

Het literair klimaat 1986-1992 (1993)

Striptease van een ui (1993)

Weg van de pijn (1994)

Uit het oog (1997)

Inktvraat (1998)

Meer speelruimte (1998)

Taats onder mannen (2001)

Je zit niet alleen in je vel (2010)

Jacq Firmin Vogelaar (Tilburg 1944 – Utrecht 2013)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Art & Literature News, EXPERIMENTAL POETRY, In Memoriam

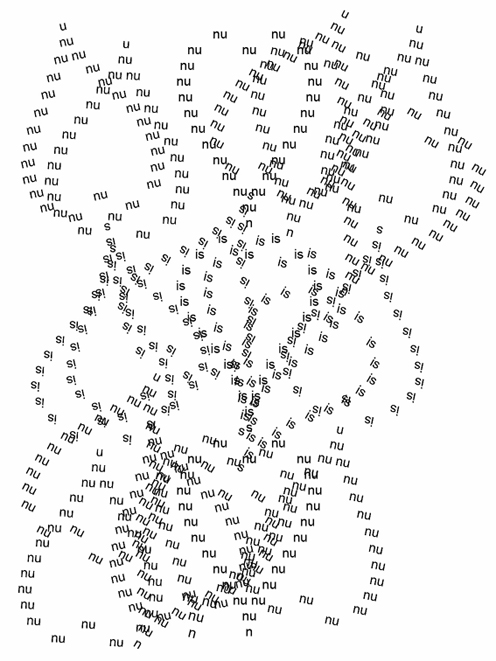

2013 Freda Kamphuis z.t.

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: *Concrete + Visual Poetry K-O, Freda Kamphuis, Kamphuis, Freda

Jasper Mikkers

ATLETE

enkels dun als polsen, kroezend haar

in blond geverfde strengen bij elkaar gebonden

te beweeglijk is ze om zich stil te houden

aan de start: atlete van geen veertig kilo

ze loopt op blote voeten

gooit oranje zolen in het licht

vrolijke extase zindert in haar ogen

ze heeft lak aan lucht als tegenwind

verbijsterend vanzelfsprekend is het grote

niets op aarde heeft gewicht wanneer ze rent

de moeiteloosheid van haar loop ontstelt de aarde

ze is haar eigen heerlijke haas

voorbij de finish neemt ze trainingsjack en water aan

op adem komen kent ze niet, geen zweten

omringd door ranke loopsters springt ze in

een halve draai omhoog en giert het uit

nog nooit heeft ze de tijd zo op de huid gezeten

en dan gebeurt het

de zwaartekracht verliest nu alle vat

ze stijgt, zweeft weg, hangt stil: ster boven onze stad

Jasper Mikkers is Stadsdichter van Tilburg

Noot: Op 1 september vond opnieuw in Tilburg de Ten Miles plaats, een loopwedstrijd voor professionels en recreanten. In het onderdeel Ladies Run, een afstand van 10 kilometer voor vrouwen, blinken altijd de Afrikaanse loopsters uit.

Jasper Mikkers Poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive M-N, City Poets / Stadsdichters, Mikkers, Jasper

Elizabeth (Lizzie) Siddal

(1829-1862)

Lord May I Come?

Life and night are falling from me,

Death and day are opening on me,

Wherever my footsteps come and go,

Life is a stony way of woe.

Lord, have I long to go?

Hallow hearts are ever near me,

Soulless eyes have ceased to cheer me:

Lord may I come to thee?

Life and youth and summer weather

To my heart no joy can gather.

Lord, lift me from life’s stony way!

Loved eyes long closed in death watch for me:

Holy death is waiting for me

Lord, may I come to-day?

My outward life feels sad and still

Like lilies in a frozen rill;

I am gazing upwards to the sun,

Lord, Lord, remembering my lost one.

O Lord, remember me!

How is it in the unknown land?

Do the dead wander hand in hand?

God, give me trust in thee.

Do we clasp dead hands and quiver

With an endless joy for ever?

Do tall white angels gaze and wend

Along the banks where lilies bend?

Lord, we know not how this may be:

Good Lord we put our faith in thee

O God, remember me.

Elizabeth (Lizzie) Siddal poems

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Lizzy Siddal, Siddal, Lizzy

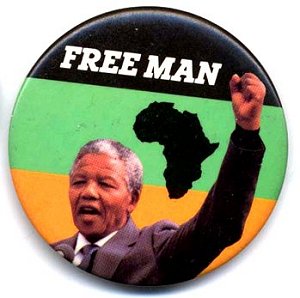

Madiba

Mohammad Ali staan kopskud-kopskud

geboë oor die bed van sy ou skermmaat

saam het hulle die fyn voetwerk van die kryt

geleer & die lees van presies die regte tyd

as swaargewigte kon hulle goed mik raak slaan

maar veral wys & strategies ontwyk

dans-dans koes vir die uitklophou van die tyd

Gedicht van Carina van der Walt

Naar aanleiding van het overlijden van Nelson Mandela (Madiba)

5 december 2013

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Carina van der Walt, Walt, Carina van der

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature