Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

Percy Bysshe Shelley

(August 4, 1792 Horsham, England – July 8, 1822 Livorno, Italy)

Nine Poems

Death

1

They die–the dead return not–Misery

Sits near an open grave and calls them over,

A Youth with hoary hair and haggard eye–

They are the names of kindred, friend and lover,

Which he so feebly calls–they all are gone–

Fond wretch, all dead! those vacant names alone,

This most familiar scene, my pain–

These tombs–alone remain.

2

Misery, my sweetest friend–oh, weep no more!

Thou wilt not be consoled–I wonder not!

For I have seen thee from thy dwelling’s door

Watch the calm sunset with them, and this spot

Was even as bright and calm, but transitory,

And now thy hopes are gone, thy hair is hoary;

This most familiar scene, my pain–

These tombs–alone remain.

Satan broken loose

(fragment)

A golden-winged Angel stood

Before the Eternal Judgement-seat:

His looks were wild, and Devils’ blood

Stained his dainty hands and feet.

The Father and the Son

Knew that strife was now begun.

They knew that Satan had broken his chain,

And with millions of daemons in his train,

Was ranging over the world again.

Before the Angel had told his tale,

A sweet and a creeping sound

Like the rushing of wings was heard around;

And suddenly the lamps grew pale–

The lamps, before the Archangels seven,

That burn continually in Heaven.

Lines to a critic

1

Honey from silkworms who can gather,

Or silk from the yellow bee?

The grass may grow in winter weather

As soon as hate in me.

2

Hate men who cant, and men who pray,

And men who rail like thee;

An equal passion to repay

They are not coy like me.

3

Or seek some slave of power and gold

To be thy dear heart’s mate;

Thy love will move that bigot cold

Sooner than me, thy hate.

4

A passion like the one I prove

Cannot divided be;

I hate thy want of truth and love–

How should I then hate thee?

To…?

1

I fear thy kisses, gentle maiden,

Thou needest not fear mine;

My spirit is too deeply laden

Ever to burthen thine.

2

I fear thy mien, thy tones, thy motion,

Thou needest not fear mine;

Innocent is the heart’s devotion

With which I worship thine.

Song of Proserpine while gathering flowers

on the Plain of Enna

1

Sacred Goddess, Mother Earth,

Thou from whose immortal bosom

Gods, and men, and beasts have birth,

Leaf and blade, and bud and blossom,

Breathe thine influence most divine

On thine own child, Proserpine.

2

If with mists of evening dew

Thou dost nourish these young flowers

Till they grow, in scent and hue,

Fairest children of the Hours,

Breathe thine influence most divine

On thine own child, Proserpine.

Autumn: A Dirge

1

The warm sun is failing, the bleak wind is wailing,

The bare boughs are sighing, the pale flowers are dying,

And the Year

On the earth her death-bed, in a shroud of leaves dead,

Is lying.

Come, Months, come away,

From November to May,

In your saddest array;

Follow the bier

Of the dead cold Year,

And like dim shadows watch by her sepulchre.

2

The chill rain is falling, the nipped worm is crawling,

The rivers are swelling, the thunder is knelling

For the Year;

The blithe swallows are flown, and the lizards each gone

To his dwelling;

Come, Months, come away;

Put on white, black, and gray;

Let your light sisters play–

Ye, follow the bier

Of the dead cold Year,

And make her grave green with tear on tear.

Death

1

Death is here and death is there,

Death is busy everywhere,

All around, within, beneath,

Above is death–and we are death.

2

Death has set his mark and seal

On all we are and all we feel,

On all we know and all we fear,

3

First our pleasures die–and then

Our hopes, and then our fears–and when

These are dead, the debt is due,

Dust claims dust–and we die too.

4

All things that we love and cherish,

Like ourselves must fade and perish;

Such is our rude mortal lot–

Love itself would, did they not.

To the moon

1

Art thou pale for weariness

Of climbing heaven and gazing on the earth,

Wandering companionless

Among the stars that have a different birth,–

And ever changing, like a joyless eye

That finds no object worth its constancy?

2

Thou chosen sister of the Spirit,

That grazes on thee till in thee it pities…

Sonnet

Ye hasten to the grave! What seek ye there,

Ye restless thoughts and busy purposes

Of the idle brain, which the world’s livery wear?

O thou quick heart, which pantest to possess

All that pale Expectation feigneth fair!

Thou vainly curious mind which wouldest guess

Whence thou didst come, and whither thou must go,

And all that never yet was known would know–

Oh, whither hasten ye, that thus ye press,

With such swift feet life’s green and pleasant path,

Seeking, alike from happiness and woe,

A refuge in the cavern of gray death?

O heart, and mind, and thoughts! what thing do you

Hope to inherit in the grave below?

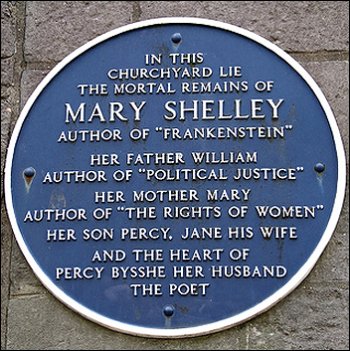

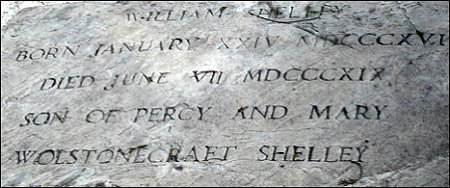

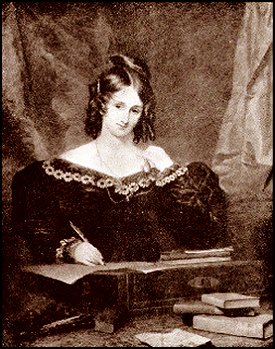

Percy Bysshe Shelley: Nine Poems

• fleursdumal.nl magazine for art & literature

More in: Archive S-T, Archive S-T, Percy Byssche Shelley, Shelley, Percy Byssche

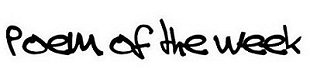

A l p h o n s e A l l a i s

(1854-1905)

Complainte Amoureuse

Oui dès l’instant que je vous vis

Beauté féroce, vous me plûtes

De l’amour qu’en vos yeux je pris

Sur-le-champ vous vous aperçûtes

Ah ! Fallait-il que vous me plussiez

Qu’ingénument je vous le dise

Qu’avec orgueil vous vous tussiez

Fallait-il que je vous aimasse

Que vous me désespérassiez

Et qu’enfin je m’opiniâtrasse

Et que je vous idolâtrasse

Pour que vous m’assassinassiez

Poem of the week – November 16, 2008

kemp=mag poetry magazine – magazine for art & literature

More in: Archive A-B

Ed Schilders

De strepen van John Keats

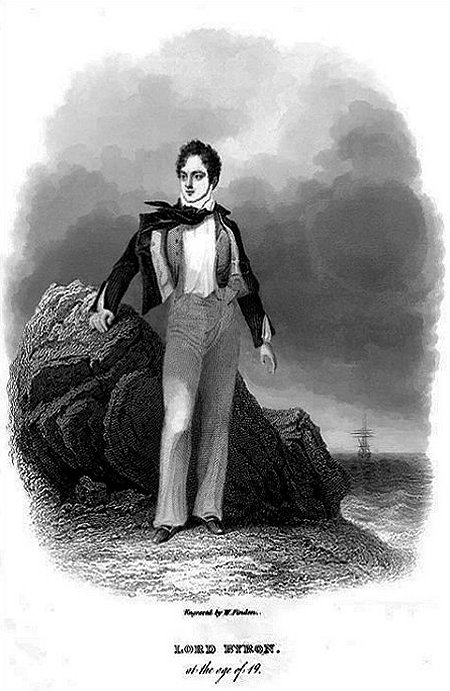

Er is een hardnekkig misverstand dat zegt, dat schrijven en strepen in een boek niet mag. Dat dat zoiets is als het papier striemen, of, nog erger, een vorm van lezers-onanie: een geperverteerde vorm van leesgedrag.

Daar is iets voor te zeggen, maar niet alles. Tenslotte zijn het de eigen boeken, bestemd voor de eigen ogen en gedachten, dus wie wil strepen of schrijven, die gaat zijn gang (zij het met inachtneming van het te hanteren schrijfmateriaal). En dan? Als de streper dood is en zijn boeken door de erfgenamen verkwanseld worden omdat ze meer van bankpapier houden? Juist dan worden strepen en margeschrifturen belangrijk. Het enige probleem dat ik met bestreepte boeken uit de tweede hand heb, is dat ik zelden te weten kan komen wie voor de lezersaccenten gezorgd heeft. Het ex-libris of het ex-bibliotheca is in onbruik geraakt, en namen op schutbladen is hoogst onvoldoende. Lezers zouden er minstens een gewoonte van moeten maken het boek te voorzien van jaartallen, en een korte indruk op een ingeplakt velletje papier. Zo zou je de 120 Dagen van Sodom van een staatssecretaris kunnen kopen, of de Gedachten van Leopardi van een taxichauffeur uit Lisse, beide werken voorzien van uitroeptekens in de marge. Oude boeken hebben een stamboom, en de lezer kan bijdragen aan de genealogie.

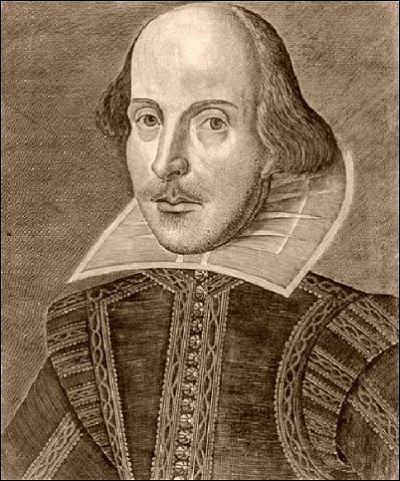

Het enige boek (in mijn kast) dat over een boek met onderstrepingen gaat, is Keats’s Shakespeare van Caroline Spurgeon (Oxford University Press, 1928). De titel zegt het al: Spurgeon onderzocht de Shakespeare-uitgave die John Keats bezat op potloodstrepen, doorhalingen en bijschriften, en vergeleek die passages met het werk van Keats zelf. Een groot deel van het boek is een nauwkeurige weergave van die pagina’s, met daarbij een voorbeeld hoe Keats zich liet inspireren door de gelezen tekst.

Die inspiratie blijkt met name in Endymion zo overweldigend te zijn dat sommigen zouden beweren dat Keats The Tempest en A Midsummer Night’s Dream geplagieerd heeft. Zo lees je niet alleen, en tegelijkertijd Spurgeon, Shakespeare en Keats, maar ook hoe Keats Shakespeare las, en hoe Spurgeon las hoe Keats Shakespeare gelezen heeft.

Vanavond knip ik dit artikel uit en zal ik het netjes en met deugdelijke lijm, in Spurgeons boek plakken. De stamboom van dit boek zal daarmee weer wat groter zijn geworden want het bevat al aardige sporen van mijn vóórlezers. Het is een bibliotheekexemplaar geweest (tussen 1935 en 1937 achtmaal uitgeleend). Toen werd het weggeschonken, en wel door het Canadian Book Centre uit Halifax. Het kwam terecht in het Moederhuis van de fraters in Tilburg dat er zijn ex-libris inplakte, en vervolgens in de centrale bibliotheek die het bestempelde. Dat de oorspronkelijke bibliotheek de Public Library van Toronto is geweest, weet ik omdat men daar met een gaatjestang de naam in de titelpagina heeft geperforeerd en op iedere prent — foto’s van de pagina’s met de strepen van Keats — een klein rond stempeltje gezet heeft om de terreur van de uitscheurders te bestrijden. Ze zijn trouwens toch heel zuinig op boeken in Toronto. Hun ex-libris wordt ten dele aan het oog onttrokken door dat van de fraters, maar de gekalligrafeerde tekst die ik nog kan lezen, zegt in vertaling: “De bibliothecaris zal ieder teruggebracht boek onderzoeken, en als hetzelfde gemarkeerd of met inkt bevlekt is, de pagina’s omgevouwen zijn, of het anderszins beschadigd is, zal de lener de waarde van het boek betalen.” Zo pak je leners aan, maar voor lezers blijft zoiets toch wel heel opmerkelijk in een boek over onderstrepingen.

.jpg)

Spurgeons boek heeft onder het frontispiece van een lezende Keats een citaat uit een van zijn brieven. “Te weten in welke houding Shakespeare zat toen hij “To be or not to be” begon op te schrijven, zoiets wordt interessant door de afstand in tijd en plaats.” Twee alinea’s hoger heeft Keats beschreven in welke houding hijzelf op dat moment zat: met de rug naar het haardvuur, aan één voet op het tapijt, de andere met de hiel enigszins opgetild. “Ik schrijf dit met “The Maid’s Tragedy”” als ondergrond, dat ik na de lunch met veel plezier gelezen heb.” Even lijkt het of hier niets anders aan de hand is dan bladvulling en behoefte aan Shakespeare, maar het toeval wil meer.

“The Maid’s Tragedy”, werd geschreven door Francis Beaumont en John Fletcher. Hun literaire samenwerking wordt geoordeeld het fraaiste toneelwerk te hebben opgeleverd op de stukken van hun tijdgenoot Shakespeare na. Beiden figureren bovendien in studies omtrent de ware identiteit van de schrijver die ‘Shakespeare’ genoemd wordt, maar van wie we geen portret hebben, geen biografie, laat staan dat we weten hoe hij achter zijn schrijftafel zat. En wat gebruikte hij als ondergrond? Met name Fletcher wordt geacht te hebben samengewerkt met Shakespeare, of Shakespeare wordt geacht bij Fletcher de inspiratie te hebben gevonden voor “Hendrik VIII”, zoals Keats zijn inspiratie vond voor “Endymion”. Strepend?

Het zoeken naar de ware biografie van Shakespeare heeft een kleine kast vol aardige, curieuze werken opgeleverd. Bacon, Essex, Raleigh, Edward de Vere, en Lord Rutland zijn de bekendste identiteiten die aan de dichter uit Stratford gegeven zijn.

Het is duidelijk dat historisch onderzoek en filologische listen de oplossing van het Shakespeare-raadsel niet meer zullen brengen. Er is, denk ik, een laatste kans. Als Shakespeare zoveel inspiratie opdeed bij andere auteurs, dan zal hij, net als Keats, ook veel gestreept hebben. Willen we ooit te weten komen wie hij was, en hoe hij zat, dan zullen we niet naar zijn verloren persoonsbewijs of zijn verdwenen manuscripten moeten zoeken maar naar de boeken die hij in zijn kast had. Naar de werken die hij las, waarin hij streepte en in de marge schreef.

.jpg)

Ed Schilders: De Strepen van John Keats

© E. Schilders

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book Stories, BOOKS. The final chapter?, Ed Schilders, John Keats, Keats, John

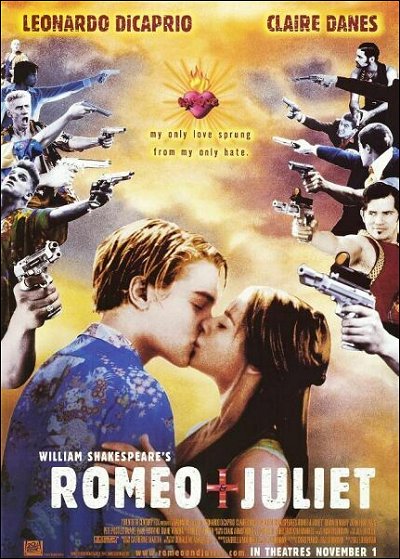

William Shakespeare

(1564-1616)

F i v e S o n n e t s

20

A woman’s face with nature’s own hand painted,

Hast thou the master mistress of my passion,

A woman’s gentle heart but not acquainted

With shifting change as is false women’s fashion,

An eye more bright than theirs, less false in rolling:

Gilding the object whereupon it gazeth,

A man in hue all hues in his controlling,

Which steals men’s eyes and women’s souls amazeth.

And for a woman wert thou first created,

Till nature as she wrought thee fell a-doting,

And by addition me of thee defeated,

By adding one thing to my purpose nothing.

But since she pricked thee out for women’s pleasure,

Mine be thy love and thy love’s use their treasure.

31

Thy bosom is endeared with all hearts,

Which I by lacking have supposed dead,

And there reigns love and all love’s loving parts,

And all those friends which I thought buried.

How many a holy and obsequious tear

Hath dear religious love stol’n from mine eye,

As interest of the dead, which now appear,

But things removed that hidden in thee lie.

Thou art the grave where buried love doth live,

Hung with the trophies of my lovers gone,

Who all their parts of me to thee did give,

That due of many, now is thine alone.

Their images I loved, I view in thee,

And thou (all they) hast all the all of me.

36

Let me confess that we two must be twain,

Although our undivided loves are one:

So shall those blots that do with me remain,

Without thy help, by me be borne alone.

In our two loves there is but one respect,

Though in our lives a separable spite,

Which though it alter not love’s sole effect,

Yet doth it steal sweet hours from love’s delight.

I may not evermore acknowledge thee,

Lest my bewailed guilt should do thee shame,

Nor thou with public kindness honour me,

Unless thou take that honour from thy name:

But do not so, I love thee in such sort,

As thou being mine, mine is thy good report.

40

Take all my loves, my love, yea take them all,

What hast thou then more than thou hadst before?

No love, my love, that thou mayst true love call,

All mine was thine, before thou hadst this more:

Then if for my love, thou my love receivest,

I cannot blame thee, for my love thou usest,

But yet be blamed, if thou thy self deceivest

By wilful taste of what thy self refusest.

I do forgive thy robbery gentle thief

Although thou steal thee all my poverty:

And yet love knows it is a greater grief

To bear love’s wrong, than hate’s known injury.

Lascivious grace, in whom all ill well shows,

Kill me with spites yet we must not be foes.

46

Mine eye and heart are at a mortal war,

How to divide the conquest of thy sight,

Mine eye, my heart thy picture’s sight would bar,

My heart, mine eye the freedom of that right,

My heart doth plead that thou in him dost lie,

(A closet never pierced with crystal eyes)

But the defendant doth that plea deny,

And says in him thy fair appearance lies.

To side this title is impanelled

A quest of thoughts, all tenants to the heart,

And by their verdict is determined

The clear eye’s moiety, and the dear heart’s part.

As thus, mine eye’s due is thy outward part,

And my heart’s right, thy inward love of heart.

kemp=mag poetry magazine

More in: Shakespeare, William

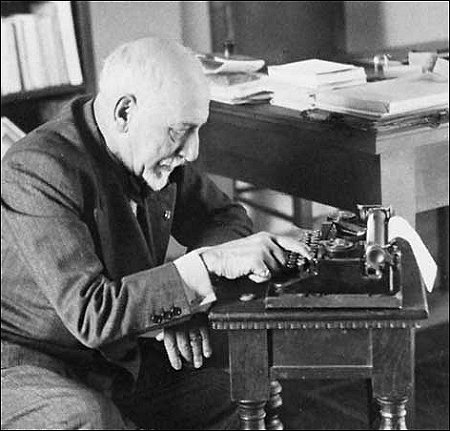

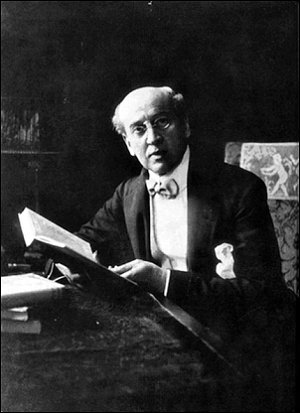

L u i g i P i r a n d e l l o

(1867-1936)

LE NUBI E LA LUNA

La nuvolaglia va stracca, raminga,

e or si sparpaglia ed ora si raduna,

quasi un soffio aspettando che la spinga

a far del bene altrove. Tutta bruna

d’acqua la terra e paga s’addormenta,

e vien dal colle sú, grande, la Luna.

Sale pian piano, come diva intenta

a vigilare, e a sé le nubi chiama.

Or questa or quella le si appressa lenta,

prende consiglio, si dirada, sciama

al lume, si raddensa, s’allontana…

Che mai la Luna con le nubi trama?

Quatta musando se ne sta la rana.

Forse ha compreso ch’ora qui ripiove?

Salta in un borro là d’acqua piovana.

Ma van le nubi a far del bene altrove.

Poem of the week

November 9, 2008

kemp=mag poetry magazine

More in: Luigi Pirandello, Pirandello, Luigi

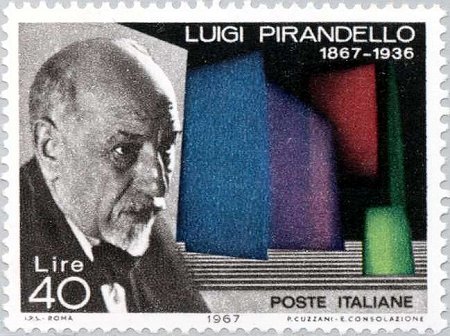

George Gordon Lord Byron

(London, 22 january 1788 – Mesolongi, 19 april 1824)

Darkness

I had a dream, which was not all a dream.

The bright sun was extinguished, and the stars

Did wander darkling in the eternal space,

Rayless, and pathless, and the icy Earth

Swung blind and blackening in the moonless air;

Morn came and went–and came, and brought no day,

And men forgot their passions in the dread

Of this their desolation; and all hearts

Were chilled into a selfish prayer for light:

And they did live by watchfires–and the thrones,

The palaces of crownéd kings–the huts,

The habitations of all things which dwell,

Were burnt for beacons; cities were consumed,

And men were gathered round their blazing homes

To look once more into each other’s face;

Happy were those who dwelt within the eye

Of the volcanos, and their mountain-torch:

A fearful hope was all the World contained;

Forests were set on fire–but hour by hour

They fell and faded–and the crackling trunks

Extinguished with a crash–and all was black.

The brows of men by the despairing light

Wore an unearthly aspect, as by fits

The flashes fell upon them; some lay down

And hid their eyes and wept; and some did rest

Their chins upon their clenchéd hands, and smiled;

And others hurried to and fro, and fed

Their funeral piles with fuel, and looked up

With mad disquietude on the dull sky,

The pall of a past World; and then again

With curses cast them down upon the dust,

And gnashed their teeth and howled: the wild birds shrieked,

And, terrified, did flutter on the ground,

And flap their useless wings; the wildest brutes

Came tame and tremulous; and vipers crawled

And twined themselves among the multitude,

Hissing, but stingless–they were slain for food:

And War, which for a moment was no more,

Did glut himself again:–a meal was bought

With blood, and each sate sullenly apart

Gorging himself in gloom: no Love was left;

All earth was but one thought–and that was Death,

Immediate and inglorious; and the pang

Of famine fed upon all entrails–men

Died, and their bones were tombless as their flesh;

The meagre by the meagre were devoured,

Even dogs assailed their masters, all save one,

And he was faithful to a corse, and kept

The birds and beasts and famished men at bay,

Till hunger clung them, or the dropping dead

Lured their lank jaws; himself sought out no food,

But with a piteous and perpetual moan,

And a quick desolate cry, licking the hand

Which answered not with a caress–he died.

The crowd was famished by degrees; but two

Of an enormous city did survive,

And they were enemies: they met beside

The dying embers of an altar-place

Where had been heaped a mass of holy things

For an unholy usage; they raked up,

And shivering scraped with their cold skeleton hands

The feeble ashes, and their feeble breath

Blew for a little life, and made a flame

Which was a mockery; then they lifted up

Their eyes as it grew lighter, and beheld

Each other’s aspects–saw, and shrieked, and died–

Even of their mutual hideousness they died,

Unknowing who he was upon whose brow

Famine had written Fiend. The World was void,

The populous and the powerful was a lump,

Seasonless, herbless, treeless, manless, lifeless–

A lump of death–a chaos of hard clay.

The rivers, lakes, and ocean all stood still,

And nothing stirred within their silent depths;

Ships sailorless lay rotting on the sea,

And their masts fell down piecemeal: as they dropped

They slept on the abyss without a surge–

The waves were dead; the tides were in their grave,

The Moon, their mistress, had expired before;

The winds were withered in the stagnant air,

And the clouds perished; Darkness had no need

Of aid from them–She was the Universe.

1816

Stanzas to Augusta

I

Though the day of my Destiny’s over,

And the star of my Fate hath declined,

Thy soft heart refused to discover

The faults which so many could find;

Though thy Soul with my grief was acquainted,

It shrunk not to share it with me,

And the Love which my Spirit hath painted

It never hath found but in Thee.

II

Then when Nature around me is smiling,

The last smile which answers to mine,

I do not believe it beguiling,

Because it reminds me of thine;

And when winds are at war with the ocean,

As the breasts I believed in with me,

If their billows excite an emotion,

It is that they bear me from Thee.

III

Though the rock of my last Hope is shivered,

And its fragments are sunk in the wave,

Though I feel that my soul is delivered

To Pain–it shall not be its slave.

There is many a pang to pursue me:

They may crush, but they shall not contemn;

They may torture, but shall not subdue me;

‘Tis of Thee that I think–not of them.

IV

Though human, thou didst not deceive me,

Though woman, thou didst not forsake,

Though loved, thou forborest to grieve me,

Though slandered, thou never couldst shake;

Though trusted, thou didst not disclaim me,

Though parted, it was not to fly,

Though watchful, ’twas not to defame me,

Nor, mute, that the world might belie.

V

Yet I blame not the World, nor despise it,

Nor the war of the many with one;

If my Soul was not fitted to prize it,

‘Twas folly not sooner to shun:

And if dearly that error hath cost me,

And more than I once could foresee,

I have found that, whatever it lost me,

It could not deprive me of Thee.

VI

From the wreck of the past, which hath perished,

Thus much I at least may recall,

It hath taught me that what I most cherished

Deserved to be dearest of all:

In the Desert a fountain is springing,

In the wide waste there still is a tree,

And a bird in the solitude singing,

Which speaks to my spirit of Thee.

1816

The Duel

1

‘Tis fifty years, and yet their fray

To us might seem but yesterday.

Tis fifty years, and three to boot,

Since, hand to hand, and foot to foot,

And heart to heart, and sword to sword,

One of our Ancestors was gored.

I’ve seen the sword that slew him; he,

The slain, stood in a like degree

To thee, as he, the Slayer, stood

(Oh had it been but other blood!)

In kin and Chieftainship to me.

Thus came the Heritage to thee.

2

To me the Lands of him who slew

Came through a line of yore renowned;

For I can boast a race as true

To Monarchs crowned, and some discrowned,

As ever Britain’s Annals knew:

For the first Conqueror gave us Ground,

And the last Conquered owned the line

Which was my mother’s, and is mine.

3

I loved thee–I will not say how,

Since things like these are best forgot:

Perhaps thou may’st imagine now

Who loved thee, and who loved thee not.

And thou wert wedded to another,

And I at last another wedded:

I am a father, thou a mother,

To Strangers vowed, with strangers bedded.

For land to land, even blood to blood–

Since leagued of yore our fathers were–

Our manors and our birthright stood;

And not unequal had I wooed,

If to have wooed thee I could dare.

But this I never dared–even yet

When naught is left but to forget.

I feel that I could only love:

To sue was never meant for me,

And least of all to sue to thee;

For many a bar, and many a feud,

Though never told, well understood

Rolled like a river wide between–

And then there was the Curse of blood,

Which even my Heart’s can not remove.

Alas! how many things have been!

Since we were friends; for I alone

Feel more for thee than can be shown.

4

How many things! I loved thee–thou

Loved’st me not: another was

The Idol of thy virgin vow,

And I was, what I am, Alas!

And what he is, and what thou art,

And what we were, is like the rest:

We must endure it as a test,

And old Ordeal of the Heart.

Stanzas

1

Could Love for ever

Run like a river,

And Time’s endeavour

Be tried in vain–

No other pleasure

With this could measure;

And like a treasure

We’d hug the chain.

But since our sighing

Ends not in dying,

And, formed for flying,

Love plumes his wing;

Then for this reason

Let’s love a season;

But let that season be only Spring.

2

When lovers parted

Feel broken-hearted,

And, all hopes thwarted,

Expect to die;

A few years older,

Ah! how much colder

They might behold her

For whom they sigh!

When linked together,

In every weather,

They pluck Love’s feather

From out his wing–

He’ll stay for ever,

But sadly shiver

Without his plumage, when past the Spring.

3

Like Chiefs of Faction,

His life is action–

A formal paction

That curbs his reign,

Obscures his glory,

Despot no more, he

Such territory

Quits with disdain.

Still, still advancing,

With banners glancing,

His power enhancing,

He must move on–

Repose but cloys him,

Retreat destroys him,

Love brooks not a degraded throne.

4

Wait not, fond lover!

Till years are over,

And then recover

As from a dream.

While each bewailing

The other’s failing.

With wrath and railing,

All hideous seem–

While first decreasing,

Yet not quite ceasing,

Wait not till teasing,

All passion blight:

If once diminished

Love’s reign is finished–

Then part in friendship,–and bid good-night.

5

So shall Affection

To recollection

The dear connection

Bring back with joy:

You had not waited

Till, tired or hated,

Your passions sated

Began to cloy.

Your last embraces

Leave no cold traces–

The same fond faces

As through the past:

And eyes, the mirrors

Of your sweet errors,

Reflect but rapture–not least though last.

6

True, separations

Ask more than patience;

What desperations

From such have risen!

But yet remaining,

What is’t but chaining

Hearts which, once waning,

Beat ‘gainst their prison?

Time can but cloy love,

And use destroy love:

The wingéd boy, Love,

Is but for boys–

You’ll find it torture

Though sharper, shorter,

To wean, and not wear out your joys.

1819

Lord Byron: Darkness & The Duel & Stanzas

kemp=mag poetry magazine

magazine for art & literature

More in: Byron, Lord

![]()

.jpg)

Museum of Lost Concepts

Disclosure 11-15

(1968-2008)

jef van kempen © kemp=mag poetry magazine

More in: *Concrete + Visual Poetry K-O, Conceptual writing, FLUXUS LEGACY, Kempen, Jef van, Visual & Concrete Poetry

.jpg)

Monica Richter poetry:

Birdlife

from ‘Roots 1968’

© kemp=mag poetry magazine

More in: Monica Richter, Richter, Monica

L o u i s C o u p e r u s

(1863-1923)

M e l o d i e

Laat, o lieve, laat

Uw blanke vingren langs

De toetsen fladdren;

En licht.

Laat, o lieve, laat

De tonen kwelend vallen, als

Kristallen dauw,

Die van uw blanke vingren drupt,

En zoet

Vervloeit.

Luchtgewiekte melodie

Zweef klaatrend op!

Of juublend in een zilverlach,

Of smeltend…

Smeltende in een vliet

Van louter tranen…

Trillend klankgetover!

Reine parelzang… stijg,

Zwellend,

In uw vol geschal!

Laat, o lieve, laat

Uw blanke vingren langs

De toetsen fladdren;

Vlindervlug

En licht…

Poem of the week

October 26, 2008

kemp=mag poetry magazine

More in: Archive C-D, Louis Couperus

J u l i a O r i g o

(1965-2005)

w i t n e s s

s t a g e o n e

I have seen many eagles

in recent years

so different

like a date without desteny

s t a g e t w o

and when you give up

-perhaps that’s the deal-

like all that died before

you get old

at any age

s t a g e t h r e e

then this misunderstanding

full of promise of modern fable

of a missing link

between age and mind

between losing home

and losing time

between you

and him

(London 1998)

kemp=mag poetry magazine

More in: Origo, Julia

.jpg)

L O U I S E A C K E R M A N N

(1813-1890)

|

M o n l i v r e Je ne vous offre plus pour toutes mélodies Pourtant, quand je m’élève à des notes pareilles, Comment ? la Liberté déchaîne ses colères ; Est-ce ma faute à moi si dans ces jours de fièvre

Jouet depuis longtemps des vents et de la houle, À l’écart, mais debout, là, dans leur lit immense C’est mon trésor unique, amassé page à page. (Paris, 7 janvier 1874) |

Poem of the week

October 19, 2008

kemp=mag poetry magazine

More in: Archive A-B

.jpg)

M U L T A T U L I

Eduard Douwes Dekker

(1820-1887)

Ik weet niet waar ik sterven zal

Ik weet niet waar ik sterven zal.

Ik heb de grote zee gezien aan de Zuidkust, toen ik daar was

met mijn vader om zout te maken.

Als ik sterf op de zee, en men werpt mijn lichaam in het diepe

water, zullen er haaien komen.

Ze zullen rondzwemmen om mijn lijk, en vragen: ‘wie van

ons zal het lichaam verslinden, dat daar daalt in het water?’

Ik zal ‘t niet horen.

Ik weet niet waar ik sterven zal.

Ik heb het huis zien branden van Pa-Ansoe, dat hijzelf had

aangestoken omdat hij mata-glap was.

Als ik sterf in een brandend huis, zullen er gloeiende stukken

hout neervallen op mijn lijk.

En buiten het huis zal een groot geroep zijn van mensen, die

water werpen om het vuur te doden.

Ik zal ‘t niet horen.

Ik weet niet waar ik sterven zal.

Ik heb de kleine Si-Oenah zien vallen uit de klapa-boom,

toen hij een klapa plukte voor zijn moeder.

Als ik val uit een klapa-boom, zal ik dood nederliggen

aan de voet, in de struiken, als Si-Oenah.

Dan zal mijn moeder niet schreien, want zij is dood. Maar

anderen zullen roepen: ‘zie, daar ligt Saïdjah!’

met harde stem.

Ik zal ‘t niet horen.

Ik weet niet waar ik sterven zal.

Ik heb het lijk gezien van Pa-Lisoe, die gestorven was van hoge ouderdom, want zijn haren waren wit.

Als ik sterf van ouderdom, met witte haren, zullen de klaag-

vrouwen om mijn lijk staan.

En zij zullen misbaar maken als de klaagvrouwen bij Pa-

lisoe’s lijk. En ook de kleinkinderen zullen schreien,

zeer luid.

Ik zal ‘t niet horen.

Ik weet niet waar ik sterven zal.

Ik heb velen gezien te Badoer, die gestorven waren. Men

kleedde hen in een wit kleed, en begroef hen in de grond.

Als ik sterf te Badoer, en men begraaft mij buiten de desa,

oostwaarts tegen de heuvel, waar ‘t gras hoog is…

Dan zal Adinda daar voorbijgaan, en de rand van haar sarong

zal zachtkens voortschuiven langs het gras…

Ik zal het horen.

(Oktober 1859)

.jpg)

Poem of the week

October 12, 2008

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature