Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

G e o r g e E l i o t

(Mary Ann Evans, 1819 – 1880)

In a London Drawingroom

The sky is cloudy, yellowed by the smoke.

For view there are the houses opposite

Cutting the sky with one long line of wall

Like solid fog: far as the eye can stretch

Monotony of surface & of form

Without a break to hang a guess upon.

No bird can make a shadow as it flies,

For all is shadow, as in ways o’erhung

By thickest canvass, where the golden rays

Are clothed in hemp. No figure lingering

Pauses to feed the hunger of the eye

Or rest a little on the lap of life.

All hurry on & look upon the ground,

Or glance unmarking at the passers by

The wheels are hurrying too, cabs, carriages

All closed, in multiplied identity.

The world seems one huge prison-house & court

Where men are punished at the slightest cost,

With lowest rate of colour, warmth & joy.

![]()

George Eliot poetry

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Archive E-F, Eliot, George

O s c a r W i l d e

(1854-1900)

Impression Du Matin

The Thames nocturne of blue and gold

Changed to a Harmony in grey:

A barge with ochre-coloured hay

Dropt from the wharf: and chill and cold

The yellow fog came creeping down

The bridges, till the houses’ walls

Seemed changed to shadows and St. Paul’s

Loomed like a bubble o’er the town.

Then suddenly arose the clang

Of waking life; the streets were stirred

With country waggons: and a bird

Flew to the glistening roofs and sang.

But one pale woman all alone,

The daylight kissing her wan hair,

Loitered beneath the gas lamps’ flare,

With lips of flame and heart of stone.

.jpg)

O s c a r W i l d e p o e t r y

k e m p i s p o e t r y m a g a z i n e

More in: Wilde, Oscar

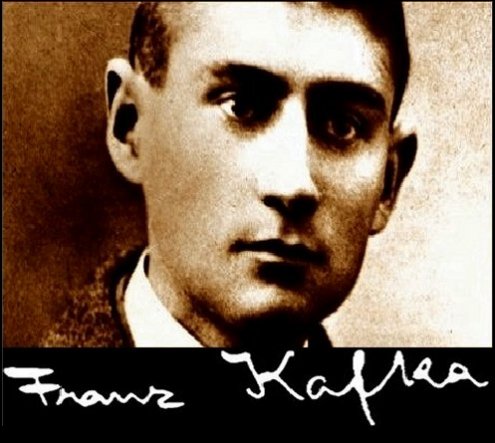

Vor dem Gesetz

Franz Kafka (1883-1924)

Vor dem Gesetz steht ein Türhüter. Zu diesem Türhüter kommt ein Mann vom Lande und bittet um Eintritt in das Gesetz. Aber der Türhüter sagt, daß er ihm jetzt den Eintritt nicht gewähren könne. Der Mann überlegt und fragt dann, ob er also später werde eintreten dürfen. »Es ist möglich,« sagt der Türhüter, »jetzt aber nicht.« Da das Tor zum Gesetz offensteht wie immer und der Türhüter beiseite tritt, bückt sich der Mann, um durch das Tor in das Innere zu sehn. Als der Türhüter das merkt, lacht er und sagt: »Wenn es dich so lockt, versuche es doch, trotz meines Verbotes hineinzugehn. Merke aber: Ich bin mächtig. Und ich bin nur der unterste Türhüter. Von Saal zu Saal stehn aber Türhüter, einer mächtiger als der andere. Schon den Anblick des dritten kann nicht einmal ich mehr ertragen.« Solche Schwierigkeiten hat der Mann vom Lande nicht erwartet; das Gesetz soll doch jedem und immer zugänglich sein, denkt er, aber als er jetzt den Türhüter in seinem Pelzmantel genauer ansieht, seine große Spitznase, den langen, dünnen, schwarzen tatarischen Bart, entschließt er sich, doch lieber zu warten, bis er die Erlaubnis zum Eintritt bekommt. Der Türhüter gibt ihm einen Schemel und läßt ihn seitwärts von der Tür sich niedersetzen. Dort sitzt er Tage und Jahre. Er macht viele Versuche, eingelassen zu werden, und ermüdet den Türhüter durch seine Bitten. Der Türhüter stellt öfters kleine Verhöre mit ihm an, fragt ihn über seine Heimat aus und nach vielem andern, es sind aber teilnahmslose Fragen, wie sie große Herren stellen, und zum Schlusse sagt er ihm immer wieder, daß er ihn noch nicht einlassen könne. Der Mann, der sich für seine Reise mit vielem ausgerüstet hat, verwendet alles, und sei es noch so wertvoll, um den Türhüter zu bestechen. Dieser nimmt zwar alles an, aber sagt dabei: »Ich nehme es nur an, damit du nicht glaubst, etwas versäumt zu haben.« Während der vielen Jahre beobachtet der Mann den Türhüter fast ununterbrochen. Er vergißt die andern Türhüter und dieser erste scheint ihm das einzige Hindernis für den Eintritt in das Gesetz.

Er verflucht den unglücklichen Zufall, in den ersten Jahren rücksichtslos und laut, später, als er alt wird, brummt er nur noch vor sich hin. Er wird kindisch, und, da er in dem jahrelangen Studium des Türhüters auch die Flöhe in seinem Pelzkragen erkannt hat, bittet er auch die Flöhe, ihm zu helfen und den Türhüter umzustimmen. Schließlich wird sein Augenlicht schwach, und er weiß nicht, ob es um ihn wirklich dunkler wird, oder ob ihn nur seine Augen täuschen. Wohl aber erkennt er jetzt im Dunkel einen Glanz, der unverlöschlich aus der Türe des Gesetzes bricht. Nun lebt er nicht mehr lange. Vor seinem Tode sammeln sich in seinem Kopfe alle Erfahrungen der ganzen Zeit zu einer Frage, die er bisher an den Türhüter noch nicht gestellt hat. Er winkt ihm zu, da er seinen erstarrenden Körper nicht mehr aufrichten kann. Der Türhüter muß sich tief zu ihm hinunterneigen, denn der Größen unterschied hat sich sehr zu ungunsten des Mannes verändert. »Was willst du denn jetzt noch wissen?« fragt der Türhüter, »du bist unersättlich.« »Alle streben doch nach dem Gesetz,« sagt der Mann, »wieso kommt es, daß in den vielen Jahren niemand außer mir Einlaß verlangt hat?« Der Türhüter erkennt, daß der Mann schon an seinem Ende ist, und, um sein vergehendes Gehör noch zu erreichen, brüllt er ihn an: »Hier konnte niemand sonst Einlaß erhalten, denn dieser Eingang war nur für dich bestimmt. Ich gehe jetzt und schließe ihn.«

Franz Kafka : Ein Landarzt. Kleine Erzählungen (1919)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive K-L, Franz Kafka, Kafka, Franz, Kafka, Franz

W i l l i a m W o r d s w o r t h

(1770-1850)

A C o m p l a i n t

There is a change–and I am poor;

Your Love hath been, nor long ago,

A Fountain at my fond Heart’s door,

Whose only business was to flow;

And flow it did; not taking heed

Of its own bounty, or my need.

What happy moments did I count!

Bless’d was I then all bliss above!

Now, for this consecrated Fount

Of murmuring, sparkling, living love,

What have I? shall I dare to tell?

A comfortless, and hidden WELL.

A Well of love–it may be deep–

I trust it is, and never dry:

What matter? if the Waters sleep

In silence and obscurity.

–Such change, and at the very door

Of my fond Heart, hath made me poor.

.jpg)

William Wordsworth poetry

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Wordsworth, William

‘Hier wil ik begraven worden in het zand’

Over Jan Naaijkens en Anton Eijkens

Door Jef van Kempen

Jan Naaijkens (1919) en Anton Eijkens (1920) zijn al bevriend vanaf het begin van de jaren veertig. Ze werkten samen in de redacties van Brabantia Nostra en Edele Brabant. In die tijd leerden zij Walter Breedveld kennen en een groot aantal andere coryfeeën van de Brabantse letteren.

Jan Naaijkens, vijfentwintig jaar lang organisator van de Groot-Kempische Cultuurdagen, ontmoette Walter Breedveld voor het eerst in 1954 toen diens roman Hexspoor werd bekroond met de literatuurprijs van de gemeente Hilvarenbeek. De auteur was gevraagd was om uit zijn werk voor te lezen en Breedveld deed dat tamelijk goed. “Hij had een nogal mooie, donkere, fluwelige stem. Maar hij wist van geen ophouden. We hadden een kwartier afgesproken, wat vrij lang is om naar een lezing te luisteren, maar Breedveld las maar door. Op een gegeven moment begon Van Duinkerken met zijn ring, quasi speels, op de tafel te tikken. Maar niemand had de moed om in te grijpen. Toen er na een half uur voor een stampvolle zaal eindelijk een eind aan kwam, slaakte iedereen een zucht van verlichting. Dat vond ik toch wel typisch voor Breedveld, die ging altijd door. Ik denk dat hij ook zo schreef”.

Frans Babylon heeft nog regelmatig bij Anton Eijkens op zolder gelogeerd. “Hij was een beetje de Poèt Maudit en omdat ik in die tijd veel Verlaine en Rimbaud las, konden we daar heerlijk over praten.” Hij erkent dat Frans Babylon, ondanks zijn zwakheden, iemand was waar je graag mee had te doen. Als Anton Eijkens moest gaan werken, zei Babylon: “Ga jij maar, ik kom mijn dag wel door. Hij ging dan overal buurten onder het genot van een fles wijn.” Als Eijkens ‘s avonds thuis kwam zat Babylon op hem te wachten.

Anton Eijkens had een grote bewondering voor Antoon Coolen. “Ik heb ooit intensief contact met hem gehad over de publicatie van een novelle in het boek Land en volk van Brabant, dat verschenen is in 1949. Maar wij konden het niet eens worden over mijn bijdrage. Hij vond een aantal dingen niet waarachtig genoeg en hij probeerde mij er toe te bewegen om die passages te herschrijven. Dat weigerde ik, schrijverstrots van een aankomend auteur, maar ik denk achteraf dat hij volkomen gelijk had.”

Jan Naaijkens leerde Coolen kennen in de eerste jaren van de oorlog. “Antoon Coolen gaf heel veel lezingen over het Brabantse en Nederlandse volkskarakter. Dat deed hij bijzonder goed, vooral in die oorlogsomstandigheden kreeg dat extra gewicht. Toen merkte ik al de merkwaardige discrepantie op tussen de man die De Peel en de mensen van De Peel beschrijft en daarbij hun taalgebruik hanteert en de zeer precieuze, keurig onberispelijk Nederlands sprekende schrijver met zijn bekende lavallière.”

Jan Naaijkens beschouwde Anton van Duinkerken als een soort halfgod. “Ik bewonderde hem om zijn werk en als mens. Als Van Duinkerken in Hilvarenbeek was, sliep hij bij mij thuis. Toen hij een keer de hele dag door had gedronken, zeulde ik met hem over straat en kwamen we langs de toren. Daar stond hij plotseling stil en zei: ‘Hier wil ik begraven worden: in het zand, in het zand, in het zand, niet in dat stinkende veen.”

Gerard Knuvelder was als persoon volkomen anders geaard dan Van Duinkerken. Hij was, net als Coolen, heel formeel. Je hoefde bij hem niet op bezoek te komen als je dat niet had aangekondigd en je werd ontvangen vanachter een bureau. Knuvelder had iets patriarchaals over zich. Als je hem beter leerde kennen, bleek het ook een hartelijke man te kunnen zijn. Op Anton Eijkens en Jan Naaijkens hebben zijn vroege geschriften veel invloed gehad, met name zijn boek Vanuit wingewesten.

Ook Pieter van der Meer de Walcheren maakte indruk op beide auteurs, vooral in de jaren dertig en veertig. Anton Eijkens: “Zoals hij schreef en de gloed van zijn geloofsovertuiging heeft toen op veel jongeren in Brabant indruk gemaakt. Je kreeg iets van die heilige aandrift mee om iets te betekenen als katholiek en als auteur. (…) Ik kijk nog wel eens naar oude foto’s, albums en zo. Maar als ik er een tijdje in zit te bladeren, denk ik bij mezelf, waar ben je nu eigenlijk mee bezig. Ik wordt er niet echt verdrietig van, maar het is wel allemaal heel erg melancholisch voor een zwakke ziel als ik.”

(Eerder gepubliceerd in: Brabants Dagblad – foto jef van kempen)

Jef van Kempen over Jan Naaijkens en Anton Eijkens

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Anton van Duinkerken, Antoon Coolen, Brabantia Nostra, Eijkens, Anton, Jan Naaijkens, Jef van Kempen, Literaire sporen

.jpg)

V i c t o r H u g o

(1802-1885)

S o i r

Dans les ravins la route oblique

Fuit. – Il voit luire au-dessus d’eux

Le ciel sinistre et métallique

A travers des arbres hideux.

Des êtres rôdent sur les rives ;

Le nénuphar nocturne éclôt ;

Des agitations furtives

Courbent l’herbe, rident le flot.

Les larges estompes de l’ombre,

Mêlant les lueurs et les eaux,

Ébauchent dans la plaine sombre

L’aspect monstrueux du chaos.

Voici que les spectres se dressent.

D’où sortent-ils ? que veulent-ils ?

Dieu ! de toutes parts apparaissent

Toutes sortes d’affreux profils !

Il marche. Les heures sont lentes.

Il voit là-haut, tout en marchant,

S’allumer ces pourpres sanglantes,

Splendeurs lugubres du couchant.

Au loin, une cloche, une enclume,

Jettent dans l’air leurs faibles coups.

A ses pieds flotte dans la brume

Le paysage immense et doux.

Tout s’éteint. L’horizon recule.

Il regarde en ce lointain noir

Se former dans le crépuscule

Les vagues figures du soir.

La plaine, qu’une brise effleure,

Ajoute, ouverte au vent des nuits,

A la solennité de l’heure

L’apaisement de tous les bruits.

A peine, ténébreux murmures,

Entend-on, dans l’espace mort,

Les palpitations obscures

De ce qui veille quand tout dort.

Les broussailles, les grès, les ormes,

Le vieux saule, le pan de mur,

Deviennent les contours difformes

De je ne sais quel monde obscur.

L’insecte aux nocturnes élytres

Imite le cri des sabbats.

Les étangs sont comme des vitres

Par où l’on voit le ciel d’en bas.

Par degrés, monts, forêts, cieux, terre,

Tout prend l’aspect terrible et grand

D’un monde entrant dans un mystère,

D’un navire dans l’ombre entrant.

.jpg)

Victor Hugo poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive G-H, Archive G-H, Hugo, Victor, Victor Hugo

Erika De Stercke

Gedicht

Draden lang

als zeewieren

gebruik je mij

glad en gemakkelijk verteerbaar

woelige woorden liggen op lakens

tussen zand en zwetende tenen

leugens, net kwallen kleven op

de badkuip

bruine randen

er waren al tekens

de muren houden hun verkalkte snavel dicht

op een halfnatte handdoek

ligt gescheurd een meisjesdroom

Erika De Stercke (Ninove 1968), woont en werkt in Gent. Ze volgde ‘Literaire creatie’ aan de Academie – afdeling Woord te Deinze en trad meermaals op bij slams en open podia in België en Nederland. Erika De Stercke was o.a. gastdichter bij Simon Vinkenoog – Onbederflijk Vers 2008 te Nijmegen. Erika De Stercke: “Schrijven geeft mij veel voldoening, soms ook wel frustratie als een woord mij niet loslaat. (…) Mijn rugzak zit vol met papierstrookjes waarop ik gedachten neerschrijf. (…) De verhalen van vrienden en gebeurtenissen in de stad, op de trein pik ik op en ze beginnen een eigen leven te leiden. Aan inspiratie geen gebrek.”

Erika De Stercke poetry

kempis poetry magazine

More in: De Stercke, Erika

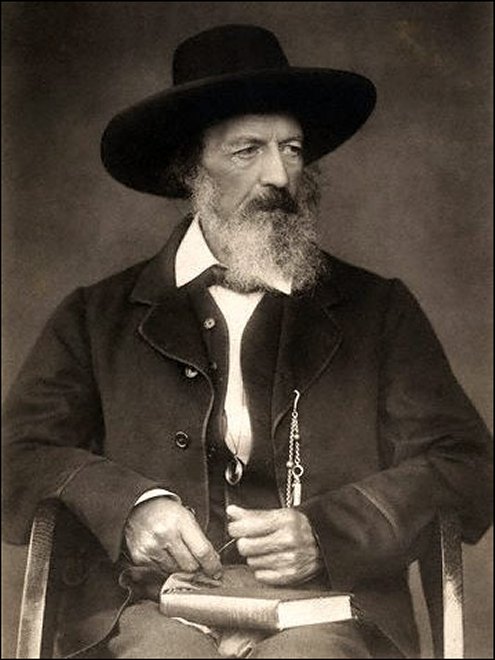

Alfred Lord Tennyson

(1809-1892)

T h e T a l k i n g O a k

Once more the gate behind me falls;

Once more before my face

I see the moulder’d Abbey-walls,

That stand within the chace.

Beyond the lodge the city lies,

Beneath its drift of smoke;

And ah! with what delighted eyes

I turn to yonder oak.

For when my passion first began,

Ere that, which in me burn’d,

The love, that makes me thrice a man,

Could hope itself return’d;

To yonder oak within the field

I spoke without restraint,

And with a larger faith appeal’d

Than Papist unto Saint.

For oft I talk’d with him apart,

And told him of my choice,

Until he plagiarised a heart,

And answer’d with a voice.

Tho’ what he whisper’d, under Heaven

None else could understand;

I found him garrulously given,

A babbler in the land.

But since I heard him make reply

Is many a weary hour;

‘Twere well to question him, and try

If yet he keeps the power.

Hail, hidden to the knees in fern,

Broad Oak of Sumner-chace,

Whose topmost branches can discern

The roofs of Sumner-place!

Say thou, whereon I carved her name,

If ever maid or spouse,

As fair as my Olivia, came

To rest beneath thy boughs.–

"O Walter, I have shelter’d here

Whatever maiden grace

The good old Summers, year by year,

Made ripe in Sumner-chace:

"Old Summers, when the monk was fat,

And, issuing shorn and sleek,

Would twist his girdle tight, and pat

The girls upon the cheek.

"Ere yet, in scorn of Peter’s-pence,

And number’d bead, and shrift,

Bluff Harry broke into the spence,

And turn’d the cowls adrift:

"And I have seen some score of those

Fresh faces, that would thrive

When his man-minded offset rose

To chase the deer at five;

"And all that from the town would stroll,

Till that wild wind made work

In which the gloomy brewer’s soul

Went by me, like a stork:

"The slight she-slips of loyal blood,

And others, passing praise,

Strait-laced, but all too full in bud

For puritanic stays:

"And I have shadow’d many a group

Of beauties, that were born

In teacup-times of hood and hoop,

Or while the patch was worn;

"And, leg and arm with love-knots gay,

About me leap’d and laugh’d

The Modish Cupid of the day,

And shrill’d his tinsel shaft.

"I swear (and else may insects prick

Each leaf into a gall)

This girl, for whom your heart is sick,

Is three times worth them all;

"For those and theirs, by Nature’s law,

Have faded long ago;

But in these latter springs I saw

Your own Olivia blow,

"From when she gamboll’d on the greens,

A baby-germ, to when

The maiden blossoms of her teens

Could number five from ten.

"I swear, by leaf, and wind, and rain

(And hear me with thine ears),

That, tho’ I circle in the grain

Five hundred rings of years–

"Yet, since I first could cast a shade,

Did never creature pass

So slightly, musically made,

So light upon the grass:

"For as to fairies, that will flit

To make the greensward fresh,

I hold them exquisitely knit,

But far too spare of flesh."

Oh, hide thy knotted knees in fern,

And overlook the chace;

And from thy topmost branch discern

The roofs of Sumner-place.

But thou, whereon I carved her name,

That oft hast heard my vows,

Declare when last Olivia came

To sport beneath thy boughs.

"O yesterday, you know, the fair

Was holden at the town;

Her father left his good arm-chair,

And rode his hunter down.

"And with him Albert came on his.

I look’d at him with joy:

As cowslip unto oxlip is,

So seems she to the boy.

"An hour had past–and, sitting straight

Within the low-wheel’d chaise,

Her mother trundled to the gate

Behind the dappled grays.

"But, as for her, she stay’d at home,

And on the roof she went,

And down the way you use to come,

She look’d with discontent.

"She left the novel half-uncut

Upon the rosewood shelf;

She left the new piano shut:

She could not please herself.

"Then ran she, gamesome as the colt,

And livelier than a lark

She sent her voice thro’ all the holt

Before her, and the park.

"A light wind chased her on the wing,

And in the chase grew wild,

As close as might be would he cling

About the darling child:

"But light as any wind that blows

So fleetly did she stir,

The flower she touch’d on dipt and rose,

And turn’d to look at her.

"And here she came, and round me play’d,

And sang to me the whole

Of those three stanzas that you made

About my ‘giant bole’;

"And in a fit of frolic mirth

She strove to span my waist:

Alas, I was so broad of girth,

I could not be embraced.

"I wish’d myself the fair young beech

That here beside me stands,

That round me, clasping each in each,

She might have lock’d her hands.

"Yet seem’d the pressure thrice as sweet

As woodbine’s fragile hold,

Or when I feel about my feet

The berried briony fold."

O muffle round thy knees with fern,

And shadow Sumner-chace!

Long may thy topmost branch discern

The roofs of Sumner-place!

But tell me, did she read the name

I carved with many vows

When last with throbbing heart I came

To rest beneath thy boughs?

"O yes, she wander’d round and round

These knotted knees of mine,

And found, and kiss’d the name she found,

And sweetly murmur’d thine.

"A teardrop trembled from its source,

And down my surface crept.

My sense of touch is something coarse,

But I believe she wept.

"Then flush’d her cheek with rosy light,

She glanced across the plain;

But not a creature was in sight:

She kiss’d me once again.

"Her kisses were so close and kind,

That, trust me on my word,

Hard wood I am, and wrinkled rind,

But yet my sap was stirr’d:

"And even into my inmost ring

A pleasure I discern’d

Like those blind motions of the Spring,

That show the year is turn’d.

"Thrice-happy he that may caress

The ringlet’s waving balm

The cushions of whose touch may press

The maiden’s tender palm.

"I, rooted here among the groves,

But languidly adjust

My vapid vegetable loves

With anthers and with dust:

"For, ah! my friend, the days were brief

Whereof the poets talk,

When that, which breathes within the leaf,

Could slip its bark and walk.

"But could I, as in times foregone,

From spray, and branch, and stem,

Have suck’d and gather’d into one

The life that spreads in them,

"She had not found me so remiss;

But lightly issuing thro’,

I would have paid her kiss for kiss

With usury thereto."

O flourish high, with leafy towers,

And overlook the lea,

Pursue thy loves among the bowers,

But leave thou mine to me.

O flourish, hidden deep in fern,

Old oak, I love thee well;

A thousand thanks for what I learn

And what remains to tell.

"’Tis little more: the day was warm;

At last, tired out with play,

She sank her head upon her arm,

And at my feet she lay.

"Her eyelids dropp’d their silken eaves.

I breathed upon her eyes

Thro’ all the summer of my leaves

A welcome mix’d with sighs.

"I took the swarming sound of life–

The music from the town–

The murmurs of the drum and fife

And lull’d them in my own.

"Sometimes I let a sunbeam slip,

To light her shaded eye;

A second flutter’d round her lip

Like a golden butterfly;

"A third would glimmer on her neck

To make the necklace shine;

Another slid, a sunny fleck,

From head to ancle fine.

"Then close and dark my arms I spread,

And shadow’d all her rest–

Dropt dews upon her golden head,

An acorn in her breast.

"But in a pet she started up,

And pluck’d it out, and drew

My little oakling from the cup,

And flung him in the dew.

"And yet it was a graceful gift–

I felt a pang within

As when I see the woodman lift

His axe to slay my kin.

"I shook him down because he was

The finest on the tree.

He lies beside thee on the grass.

O kiss him once for me.

"O kiss him twice and thrice for me,

That have no lips to kiss,

For never yet was oak on lea

Shall grow so fair as this."

Step deeper yet in herb and fern,

Look further thro’ the chace,

Spread upward till thy boughs discern

The front of Sumner-place.

This fruit of thine by Love is blest,

That but a moment lay

Where fairer fruit of Love may rest

Some happy future day.

I kiss it twice, I kiss it thrice,

The warmth it thence shall win

To riper life may magnetise

The baby-oak within.

But thou, while kingdoms overset,

Or lapse from hand to hand,

Thy leaf shall never fail, nor yet

Thine acorn in the land.

May never saw dismember thee,

Nor wielded axe disjoint,

That art the fairest-spoken tree

From here to Lizard-point.

O rock upon thy towery top

All throats that gurgle sweet!

All starry culmination drop

Balm-dews to bathe thy feet!

All grass of silky feather grow–

And while he sinks or swells

The full south-breeze around thee blow

The sound of minster bells.

The fat earth feed thy branchy root,

That under deeply strikes!

The northern morning o’er thee shoot

High up, in silver spikes!

Nor ever lightning char thy grain,

But, rolling as in sleep,

Low thunders bring the mellow rain,

That makes thee broad and deep!

And hear me swear a solemn oath,

That only by thy side

Will I to Olive plight my troth,

And gain her for my bride.

And when my marriage morn may fall,

She, Dryad-like, shall wear

Alternate leaf and acorn-ball

In wreath about her hair.

And I will work in prose and rhyme,

And praise thee more in both

Than bard has honour’d beech or lime,

Or that Thessalian growth,

In which the swarthy ringdove sat,

And mystic sentence spoke;

And more than England honours that,

Thy famous brother-oak,

Wherein the younger Charles abode

Till all the paths were dim,

And far below the Roundhead rode,

And humm’d a surly hymn.

.jpg)

Alfred Lord Tennyson poetry

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Tennyson, Alfred Lord

.jpg)

William Shakespeare

(1564-1616)

THE SONNETS

32

If thou survive my well-contented day,

When that churl death my bones with dust shall cover

And shalt by fortune once more re-survey

These poor rude lines of thy deceased lover:

Compare them with the bett’ring of the time,

And though they be outstripped by every pen,

Reserve them for my love, not for their rhyme,

Exceeded by the height of happier men.

O then vouchsafe me but this loving thought,

‘Had my friend’s Muse grown with this growing age,

A dearer birth than this his love had brought

To march in ranks of better equipage:

But since he died and poets better prove,

Theirs for their style I’ll read, his for his love’.

![]()

kempis poetry magazine

More in: -Shakespeare Sonnets

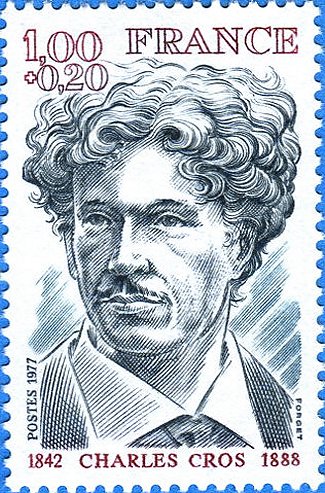

C h a r l e s C r o s

(1842-1888)

L e s q u a t r e s a i s o n s

Les quatre saisons – L’automne

L’automne fait les bruits froissés

De nos tumultueux baisers.

Dans l’eau tombent les feuilles sèches

Et sur ses yeux, les folles mèches.

Voici les pèches, les raisins,

J’aime mieux sa joue et ses seins.

Que me fait le soir triste et rouge,

Quand sa lèvre boudeuse bouge ?

Le vin qui coule des pressoirs

Est moins traître que ses yeux noirs

Les quatre saisons – L’été

En été les lis et les roses

Jalousaient ses tons et ses poses,

La nuit, par l’odeur des tilleuls

Nous nous en sommes allés seuls.

L’odeur de son corps, sur la mousse,

Est plus enivrante et plus douce.

En revenant le long des blés,

Nous étions tous deux bien troublés.

Comme les blés que le vent frôle,

Elle ployait sur mon épaule.

Les quatre saisons – L’hiver

C’est l’hiver. Le charbon de terre

Flambe en ma chambre solitaire.

La neige tombe sur les toits.

Blanche ! Oh, ses beaux seins blancs et froids !

Même sillage aux cheminées

Qu’en ses tresses disséminées.

Au bal, chacun jette, poli,

Les mots féroces de l’oubli,

L’eau qui chantait s’est prise en glace,

Amour, quel ennui te remplace !

Les quatre saisons – Le printemps

Au printemps, c’est dans les bois nus

Qu’un jour nous nous sommes connus.

Les bourgeons poussaient vapeur verte.

L’amour fut une découverte.

Grâce aux lilas, grâce aux muguets,

De rêveurs nous devînmes gais.

Sous la glycine et le cytise,

Tous deux seuls, que faut-il qu’on dise ?

Nous n’aurions rien dit, réséda,

Sans ton parfum qui nous aida.

.jpg)

Charles Cros poetry

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Archive C-D, Cros, Charles

Leo van der Sterren

Kleine litanie van oude zielen

diep in droge breinen

linksaf de hoek om

de markering volgen

haarspeldbocht als darmrivier

ondergronds door hersens

verbindt de kwab de lob

bes en besje uil geknapt

synaps maar in de gang

staat een beeld van geest

van marmer of van geest

’t is niet uit te maken

dat beeld torent hoog

maar laag is het de ziel

de broedplaats van het

ongenode dat duwt en

perst de schuwheid uit

de luwte in de zenuwen

een gruwel maar de hersens

halen hun verhalen

in de uitstreken de uithalen

uithoeken van zichzelf

en jagen ze furieus en wit

heet het huis uit woonstee der

ziel rechtsaf de hoek om

wegbewijzering weg

gewezen dan kwijt

verloren en terecht de hersens

vermist meanderend

de harde horde in

van de sensuele symfonie

van de van de weet

veel vector lamstraal

wrede voren harde lente

want de horde tiert op jong

en jong doet pijn in oude

en verzaakte zielen in halve

en vermolmde lijven

met breinen uitgeloogd

Leo van der Sterren poetry

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Sterren, Leo van der

Georg Trakl

(1887-1914)

Der Abend

Mit toten Heldengestalten

Erfüllst du Mond

Die schweigenden Wälder,

Sichelmond-

Mit der sanften Umarmung

Der Liebenden,

Den Schatten berühmter Zeiten

Die modernden Felsen rings;

So bläulich erstrahlt es

Gegen die Stadt hin,

Wo kalt und böse

Ein verwesend Geschlecht wohnt,

Der weißen Enkel

Dunkle Zukunft bereitet.

Ihr mondverschlungnen Schatten

Aufseufzend im leeren Kristall

Des Bergsees.

.jpg)

Georg Trakl poetry

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Trakl, Georg

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature