Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

.jpg)

P. A. d e G é n e s t e t

(1829 – 1861)

Twee Gedichten

Album

Weggedorde en weggeteerde blâren

Bloemekens van geur en kleur beroofd,

Blonde bruine, zwarte, zijden haren,

Lokken van zoo menig dierbaar hoofd,

Verzen van verliefde dichtersnaren,

Zoete nonsens onzer kinderjaren!

Rozenstrikken door den tijd verdoofd:

Woordjes…. ach zoo geurig eens – nog teeder,

Die mij aarde en hemel hebt beloofd….

Plechtige eeden van een kraaieveder!

Ach, hoe mocht ik eertijds uren lang,

Paradijs van bloemen en gezang,

Bij den schat van uw satijnen bladen,

’t Peinzend hoofd in liefde en weelde baden!

Uw bescheen der Hope stralenglans,

’t Dwepend hart mocht aan uw geur zich laven:

Ach! een aaklig kerkhof zijt gij thans;

Bij elk dorrend bloempje van uw krans

Ligt een liefde, een vreugd, een droom begraven.

Bij het beekje

Terwijl ik staar in ’t spiegelglad

Van ’t zilvren nat,

Schud ik mijn hoofd; wie ben ik?

Ja, hooge Hemel: Hoe, wie wat?

Wat wil, wat weet, wat ken ik?

Zie hoe hij lacht – die dwaas, die guit,

Die leelijkert in ’t water:

Mijn help! mij–zelven lach ik uit

Met wonderlijk geschater.

O menschenhart, o menschenhart,

Verschrikt, verward,

Vol zonden, dwaasheên, wonden:

Ik gaf mijn zoetste en liefste smart,

Mocht ik mij–zelf doorgronden.

Een lach klinkt uit het golvenbed;

Dat wil zich–zelf begrijpen!

Zoudt ge ook uw beeltnis hier te–met

In de ooren willen knijpen?

.jpg)

P.A. de Génestet gedichten

k e m p i s p o e t r y m a g a z i n e

More in: Génestet, P.A. de

G e o r g e E l i o t

(Mary Ann Evans, 1819 – 1880)

I Grant You Ample Leave

"I grant you ample leave

To use the hoary formula ‘I am’

Naming the emptiness where thought is not;

But fill the void with definition, ‘I’

Will be no more a datum than the words

You link false inference with, the ‘Since’ & ‘so’

That, true or not, make up the atom-whirl.

Resolve your ‘Ego’, it is all one web

With vibrant ether clotted into worlds:

Your subject, self, or self-assertive ‘I’

Turns nought but object, melts to molecules,

Is stripped from naked Being with the rest

Of those rag-garments named the Universe.

Or if, in strife to keep your ‘Ego’ strong

You make it weaver of the etherial light,

Space, motion, solids & the dream of Time —

Why, still ’tis Being looking from the dark,

The core, the centre of your consciousness,

That notes your bubble-world: sense, pleasure, pain,

What are they but a shifting otherness,

Phantasmal flux of moments? –"

.jpg)

George Eliot poetry

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Eliot, George

.jpg)

Virginia Woolf

(1882-1941)

George Eliot

To read George Eliot attentively is to become aware how little one knows about her. It is also to become aware of the credulity, not very creditable to one’s insight, with which, half consciously and partly maliciously, one had accepted the late Victorian version of a deluded woman who held phantom sway over subjects even more deluded than herself. At what moment and by what means her spell was broken it is difficult to ascertain. Some people attribute it to the publication of her Life. Perhaps George Meredith, with his phrase about the “mercurial little showman” and the “errant woman” on the daïs, gave point and poison to the arrows of thousands incapable of aiming them so accurately, but delighted to let fly. She became one of the butts for youth to laugh at, the convenient symbol of a group of serious people who were all guilty of the same idolatry and could be dismissed with the same scorn. Lord Acton had said that she was greater than Dante; Herbert Spencer exempted her novels, as if they were not novels, when he banned all fiction from the London Library. She was the pride and paragon of her sex. Moreover, her private record was not more alluring than her public. Asked to describe an afternoon at the Priory, the story-teller always intimated that the memory of those serious Sunday afternoons had come to tickle his sense of humour. He had been so much alarmed by the grave lady in her low chair; he had been so anxious to say the intelligent thing. Certainly, the talk had been very serious, as a note in the fine clear hand of the great novelist bore witness. It was dated on the Monday morning, and she accused herself of having spoken without due forethought of Marivaux when she meant another; but no doubt, she said, her listener had already supplied the correction. Still, the memory of talking about Marivaux to George Eliot on a Sunday afternoon was not a romantic memory. It had faded with the passage of the years. It had not become picturesque.

Indeed, one cannot escape the conviction that the long, heavy face with its expression of serious and sullen and almost equine power has stamped itself depressingly upon the minds of people who remember George Eliot, so that it looks out upon them from her pages. Mr. Gosse has lately described her as he saw her driving through London in a victoria:

a large, thick-set sybil, dreamy and immobile, whose massive features, somewhat grim when seen in profile, were incongruously bordered by a hat, always in the height of Paris fashion, which in those days commonly included an immense ostrich feather.

Lady Ritchie, with equal skill, has left a more intimate indoor portrait:

She sat by the fire in a beautiful black satin gown, with a green shaded lamp on the table beside her, where I saw German books lying and pamphlets and ivory paper-cutters. She was very quiet and noble, with two steady little eyes and a sweet voice. As I looked I felt her to be a friend, not exactly a personal friend, but a good and benevolent impulse.

A scrap of her talk is preserved. “We ought to respect our influence,” she said. “We know by our own experience how very much others affect our lives, and we must remember that we in turn must have the same effect upon others.” Jealously treasured, committed to memory, one can imagine recalling the scene, repeating the words, thirty years later and suddenly, for the first time, bursting into laughter.

In all these records one feels that the recorder, even when he was in the actual presence, kept his distance and kept his head, and never read the novels in later years with the light of a vivid, or puzzling, or beautiful personality dazzling in his eyes. In fiction, where so much of personality is revealed, the absence of charm is a great lack; and her critics, who have been, of course, mostly of the opposite sex, have resented, half consciously perhaps, her deficiency in a quality which is held to be supremely desirable in women. George Eliot was not charming; she was not strongly feminine; she had none of those eccentricities and inequalities of temper which give to so many artists the endearing simplicity of children. One feels that to most people, as to Lady Ritchie, she was “not exactly a personal friend, but a good and benevolent impulse”. But if we consider these portraits more closely we shall find that they are all the portraits of an elderly celebrated woman, dressed in black satin, driving in her victoria, a woman who has been through her struggle and issued from it with a profound desire to be of use to others, but with no wish for intimacy, save with the little circle who had known her in the days of her youth. We know very little about the days of her youth; but we do know that the culture, the philosophy, the fame, and the influence were all built upon a very humble foundation — she was the grand-daughter of a carpenter.

The first volume of her life is a singularly depressing record. In it we see her raising herself with groans and struggles from the intolerable boredom of petty provincial society (her father had risen in the world and become more middle class, but less picturesque) to be the assistant editor of a highly intellectual London review, and the esteemed companion of Herbert Spencer. The stages are painful as she reveals them in the sad soliloquy in which Mr. Cross condemned her to tell the story of her life. Marked in early youth as one “sure to get something up very soon in the way of a clothing club”, she proceeded to raise funds for restoring a church by making a chart of ecclesiastical history; and that was followed by a loss of faith which so disturbed her father that he refused to live with her. Next came the struggle with the translation of Strauss, which, dismal and “soul-stupefying” in itself, can scarcely have been made less so by the usual feminine tasks of ordering a household and nursing a dying father, and the distressing conviction, to one so dependent upon affection, that by becoming a blue-stocking she was forfeiting her brother’s respect. “I used to go about like an owl,” she said, “to the great disgust of my brother.” “Poor thing,” wrote a friend who saw her toiling through Strauss with a statue of the risen Christ in front of her, “I do pity her sometimes, with her pale sickly face and dreadful headaches, and anxiety, too, about her father.” Yet, though we cannot read the story without a strong desire that the stages of her pilgrimage might have been made, if not more easy, at least more beautiful, there is a dogged determination in her advance upon the citadel of culture which raises it above our pity. Her development was very slow and very awkward, but it had the irresistible impetus behind it of a deep-seated and noble ambition. Every obstacle at length was thrust from her path. She knew every one. She read everything. Her astonishing intellectual vitality had triumphed. Youth was over, but youth had been full of suffering. Then, at the age of thirty-five, at the height of her powers, and in the fulness of her freedom, she made the decision which was of such profound moment to her and still matters even to us, and went to Weimar, alone with George Henry Lewes.

The books which followed so soon after her union testify in the fullest manner to the great liberation which had come to her with personal happiness. In themselves they provide us with a plentiful feast. Yet at the threshold of her literary career one may find in some of the circumstances of her life influences that turned her mind to the past, to the country village, to the quiet and beauty and simplicity of childish memories and away from herself and the present. We understand how it was that her first book was Scenes of Clerical Life, and not Middlemarch. Her union with Lewes had surrounded her with affection, but in view of the circumstances and of the conventions it had also isolated her. “I wish it to be understood”, she wrote in 1857, “that I should never invite any one to come and see me who did not ask for the invitation.” She had been “cut off from what is called the world”, she said later, but she did not regret it. By becoming thus marked, first by circumstances and later, inevitably, by her fame, she lost the power to move on equal terms unnoted among her kind; and the loss for a novelist was serious. Still, basking in the light and sunshine of Scenes of Clerical Life, feeling the large mature mind spreading itself with a luxurious sense of freedom in the world of her “remotest past”, to speak of loss seems inappropriate. Everything to such a mind was gain. All experience filtered down through layer after layer of perception and reflection, enriching and nourishing. The utmost we can say, in qualifying her attitude towards fiction by what little we know of her life, is that she had taken to heart certain lessons not usually learnt early, if learnt at all, among which, perhaps, the most branded upon her was the melancholy virtue of tolerance; her sympathies are with the everyday lot, and play most happily in dwelling upon the homespun of ordinary joys and sorrows. She has none of that romantic intensity which is connected with a sense of one’s own individuality, unsated and unsubdued, cutting its shape sharply upon the background of the world. What were the loves and sorrows of a snuffy old clergyman, dreaming over his whisky, to the fiery egotism of Jane Eyre? The beauty of those first books, Scenes of Clerical Life, Adam Bede, The Mill on the Floss, is very great. It is impossible to estimate the merit of the Poysers, the Dodsons, the Gilfils, the Bartons, and the rest with all their surroundings and dependencies, because they have put on flesh and blood and we move among them, now bored, now sympathetic, but always with that unquestioning acceptance of all that they say and do, which we accord to the great originals only. The flood of memory and humour which she pours so spontaneously into one figure, one scene after another, until the whole fabric of ancient rural England is revived, has so much in common with a natural process that it leaves us with little consciousness that there is anything to criticise. We accept; we feel the delicious warmth and release of spirit which the great creative writers alone procure for us. As one comes back to the books after years of absence they pour out, even against our expectation, the same store of energy and heat, so that we want more than anything to idle in the warmth as in the sun beating down from the red orchard wall. If there is an element of unthinking abandonment in thus submitting to the humours of Midland farmers and their wives, that, too, is right in the circumstances. We scarcely wish to analyse what we feel to be so large and deeply human. And when we consider how distant in time the world of Shepperton and Hayslope is, and how remote the minds of farmer and agricultural labourers from those of most of George Eliot’s readers, we can only attribute the ease and pleasure with which we ramble from house to smithy, from cottage parlour to rectory garden, to the fact that George Eliot makes us share their lives, not in a spirit of condescension or of curiosity, but in a spirit of sympathy. She is no satirist. The movement of her mind was too slow and cumbersome to lend itself to comedy. But she gathers in her large grasp a great bunch of the main elements of human nature and groups them loosely together with a tolerant and wholesome understanding which, as one finds upon re-reading, has not only kept her figures fresh and free, but has given them an unexpected hold upon our laughter and tears. There is the famous Mrs. Poyser. It would have been easy to work her idiosyncrasies to death, and, as it is, perhaps, George Eliot gets her laugh in the same place a little too often. But memory, after the book is shut, brings out, as sometimes in real life, the details and subtleties which some more salient characteristic has prevented us from noticing at the time. We recollect that her health was not good. There were occasions upon which she said nothing at all. She was patience itself with a sick child. She doted upon Totty. Thus one can muse and speculate about the greater number of George Eliot’s characters and find, even in the least important, a roominess and margin where those qualities lurk which she has no call to bring from their obscurity.

But in the midst of all this tolerance and sympathy there are, even in the early books, moments of greater stress. Her humour has shown itself broad enough to cover a wide range of fools and failures, mothers and children, dogs and flourishing midland fields, farmers, sagacious or fuddled over their ale, horse-dealers, inn-keepers, curates, and carpenters. Over them all broods a certain romance, the only romance that George Eliot allowed herself — the romance of the past. The books are astonishingly readable and have no trace of pomposity or pretence. But to the reader who holds a large stretch of her early work in view it will become obvious that the mist of recollection gradually withdraws. It is not that her power diminishes, for, to our thinking, it is at its highest in the mature Middlemarch, the magnificent book which with all its imperfections is one of the few English novels written for grown-up people. But the world of fields and farms no longer contents her. In real life she had sought her fortunes elsewhere; and though to look back into the past was calming and consoling, there are, even in the early works, traces of that troubled spirit, that exacting and questioning and baffled presence who was George Eliot herself. In Adam Bede there is a hint of her in Dinah. She shows herself far more openly and completely in Maggie in The Mill on the Floss. She is Janet in Janet’s Repentance, and Romola, and Dorothea seeking wisdom and finding one scarcely knows what in marriage with Ladislaw. Those who fall foul of George Eliot do so, we incline to think, on account of her heroines; and with good reason; for there is no doubt that they bring out the worst of her, lead her into difficult places, make her self-conscious, didactic, and occasionally vulgar. Yet if you could delete the whole sisterhood you would leave a much smaller and a much inferior world, albeit a world of greater artistic perfection and far superior jollity and comfort. In accounting for her failure, in so far as it was a failure, one recollects that she never wrote a story until she was thirty-seven, and that by the time she was thirty-seven she had come to think of herself with a mixture of pain and something like resentment. For long she preferred not to think of herself at all. Then, when the first flush of creative energy was exhausted and self-confidence had come to her, she wrote more and more from the personal standpoint, but she did so without the unhesitating abandonment of the young. Her self-consciousness is always marked when her heroines say what she herself would have said. She disguised them in every possible way. She granted them beauty and wealth into the bargain; she invented, more improbably, a taste for brandy. But the disconcerting and stimulating fact remained that she was compelled by the very power of her genius to step forth in person upon the quiet bucolic scene.

The noble and beautiful girl who insisted upon being born into the Mill on the Floss is the most obvious example of the ruin which a heroine can strew about her. Humour controls her and keeps her lovable so long as she is small and can be satisfied by eloping with the gipsies or hammering nails into her doll; but she develops; and before George Eliot knows what has happened she has a full-grown woman on her hands demanding what neither gipsies, nor dolls, nor St. Ogg’s itself is capable of giving her. First Philip Wakem is produced, and later Stephen Guest. The weakness of the one and the coarseness of the other have often been pointed out; but both, in their weakness and coarseness, illustrate not so much George Eliot’s inability to draw the portrait of a man, as the uncertainty, the infirmity, and the fumbling which shook her hand when she had to conceive a fit mate for a heroine. She is in the first place driven beyond the home world she knew and loved, and forced to set foot in middle-class drawing-rooms where young men sing all the summer morning and young women sit embroidering smoking-caps for bazaars. She feels herself out of her element, as her clumsy satire of what she calls “good society” proves.

Good society has its claret and its velvet carpets, its dinner engagements six weeks deep, its opera, and its faery ball rooms . . . gets its science done by Faraday and its religion by the superior clergy who are to be met in the best houses; how should it have need of belief and emphasis?

There is no trace of humour or insight there, but only the vindictiveness of a grudge which we feel to be personal in its origin. But terrible as the complexity of our social system is in its demands upon the sympathy and discernment of a novelist straying across the boundaries, Maggie Tulliver did worse than drag George Eliot from her natural surroundings. She insisted upon the introduction of the great emotional scene. She must love; she must despair; she must be drowned clasping her brother in her arms. The more one examines the great emotional scenes the more nervously one anticipates the brewing and gathering and thickening of the cloud which will burst upon our heads at the moment of crisis in a shower of disillusionment and verbosity. It is partly that her hold upon dialogue, when it is not dialect, is slack; and partly that she seems to shrink with an elderly dread of fatigue from the effort of emotional concentration. She allows her heroines to talk too much. She has little verbal felicity. She lacks the unerring taste which chooses one sentence and compresses the heart of the scene within that. “Whom are you going to dance with?” asked Mr. Knightley, at the Westons’ ball. “With you, if you will ask me,” said Emma; and she has said enough. Mrs. Casaubon would have talked for an hour and we should have looked out of the window.

Yet, dismiss the heroines without sympathy, confine George Eliot to the agricultural world of her “remotest past”, and you not only diminish her greatness but lose her true flavour. That greatness is here we can have no doubt. The width of the prospect, the large strong outlines of the principal features, the ruddy light of the early books, the searching power and reflective richness of the later tempt us to linger and expatiate beyond our limits. But it is upon the heroines that we would cast a final glance. “I have always been finding out my religion since I was a little girl,” says Dorothea Casaubon. “I used to pray so much — now I hardly ever pray. I try not to have desires merely for myself. . . .” She is speaking for them all. That is their problem. They cannot live without religion, and they start out on the search for one when they are little girls. Each has the deep feminine passion for goodness, which makes the place where she stands in aspiration and agony the heart of the book — still and cloistered like a place of worship, but that she no longer knows to whom to pray. In learning they seek their goal; in the ordinary tasks of womanhood; in the wider service of their kind. They do not find what they seek, and we cannot wonder. The ancient consciousness of woman, charged with suffering and sensibility, and for so many ages dumb, seems in them to have brimmed and overflowed and uttered a demand for something — they scarcely know what — for something that is perhaps incompatible with the facts of human existence. George Eliot had far too strong an intelligence to tamper with those facts, and too broad a humour to mitigate the truth because it was a stern one. Save for the supreme courage of their endeavour, the struggle ends, for her heroines, in tragedy, or in a compromise that is even more melancholy. But their story is the incomplete version of the story of George Eliot herself. For her, too, the burden and the complexity of womanhood were not enough; she must reach beyond the sanctuary and pluck for herself the strange bright fruits of art and knowledge. Clasping them as few women have ever clasped them, she would not renounce her own inheritance — the difference of view, the difference of standard — nor accept an inappropriate reward. Thus we behold her, a memorable figure, inordinately praised and shrinking from her fame, despondent, reserved, shuddering back into the arms of love as if there alone were satisfaction and, it might be, justification, at the same time reaching out with “a fastidious yet hungry ambition” for all that life could offer the free and inquiring mind and confronting her feminine aspirations with the real world of men. Triumphant was the issue for her, whatever it may have been for her creations, and as we recollect all that she dared and achieved, how with every obstacle against her — sex and health and convention — she sought more knowledge and more freedom till the body, weighted with its double burden, sank worn out, we must lay upon her grave whatever we have it in our power to bestow of laurel and rose.

Virginia Woolf: The Common Reader

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Eliot, George, Woolf, Virginia

![]()

Front 242 singer and Psy’Aviah

bring an Arthur Rimbaud poem on music

Electronic band Psy’Aviah and electronic pioneer Jean-Luc De Meyer (known from the cult 80s band Front 242) have collaborated on a track called “Ophélie”, based on the poem by Arthur Rimbaud. Jean-Luc De Meyer sings the poem in the original language.

Watch the small teaser clip: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2Tb0LEDIr8E

The track appears on their new album “Eclectric” which is released by Alfa Matrix records. Psy’Aviah has a tradition in inviting guests to the album, and this isn’t the first poem they brought. In 2007 they even reach the top 20 of the international BBC Next Big Thing contest with the track Moments featuring poet Suzi Q. Smith.

More info at www.psyaviah.com

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive Q-R, Art & Literature News, Arthur Rimbaud, Rimbaud, Arthur

![]()

Mathilde Wesendonck

(1828 – 1902)

5 Lieder

Lied 1: Der Engel

In der Kindheit frühen Tagen

Hört ich oft von Engeln sagen,

Die des Himmels hehre Wonne

Tauschen mit der Erdensonne,

Daß, wo bang ein Herz in Sorgen

Schmachtet vor der Welt verborgen,

Daß, wo still es will verbluten,

Und vergehn in Tränenfluten,

Daß, wo brünstig sein Gebet

Einzig um Erlösung fleht,

Da der Engel niederschwebt,

Und es sanft gen Himmel hebt.

Ja, es stieg auch mir ein Engel nieder,

Und auf leuchtendem Gefieder

Führt er, ferne jedem Schmerz,

Meinen Geist nun himmelwärts!

Lied 2: Stehe still!

Sausendes, brausendes Rad der Zeit,

Messer du der Ewigkeit;

Leuchtende Sphären im weiten All,

Die ihr umringt den Weltenball;

Urewige Schöpfung, halte doch ein,

Genug des Werdens, laß mich sein!

Halte an dich, zeugende Kraft,

Urgedanke, der ewig schafft!

Hemmet den Atem, stillet den Drang,

Schweiget nur eine Sekunde lang!

Schwellende Pulse, fesselt den Schlag;

Ende, des Wollens ew’ger Tag!

Daß in selig süßem Vergessen

Ich mög alle Wonnen ermessen!

Wenn Aug’ in Auge wonnig trinken,

Seele ganz in Seele versinken;

Wesen in Wesen sich wiederfindet,

Und alles Hoffens Ende sich kündet,

Die Lippe verstummt in staunendem Schweigen,

Keinen Wunsch mehr will das Innre zeugen:

Erkennt der Mensch des Ew’gen Spur,

Und löst dein Rätsel, heil’ge Natur!

Lied 3: Im Treibhaus

Hochgewölbte Blätterkronen,

Baldachine von Smaragd,

Kinder ihr aus fernen Zonen,

Saget mir, warum ihr klagt?

Schweigend neiget ihr die Zweige,

Malet Zeichen in die Luft,

Und der Leiden stummer Zeuge

Steiget aufwärts, süßer Duft.

Weit in sehnendem Verlangen

Breitet ihr die Arme aus,

Und umschlinget wahnbefangen

Öder Leere nicht’gen Graus.

Wohl, ich weiß es, arme Pflanze;

Ein Geschicke teilen wir,

Ob umstrahlt von Licht und Glanze,

Unsre Heimat ist nicht hier!

Und wie froh die Sonne scheidet

Von des Tages leerem Schein,

Hüllet der, der wahrhaft leidet,

Sich in Schweigens Dunkel ein.

Stille wird’s, ein säuselnd Weben

Füllet bang den dunklen Raum:

Schwere Tropfen seh ich schweben

An der Blätter grünem Saum.

Lied 4: Schmerzen

Sonne, weinest jeden Abend

Dir die schönen Augen rot,

Wenn im Meeresspiegel badend

Dich erreicht der frühe Tod;

Doch erstehst in alter Pracht,

Glorie der düstren Welt,

Du am Morgen neu erwacht,

Wie ein stolzer Siegesheld!

Ach, wie sollte ich da klagen,

Wie, mein Herz, so schwer dich sehn,

Muß die Sonne selbst verzagen,

Muß die Sonne untergehn?

Und gebieret Tod nur Leben,

Geben Schmerzen Wonne nur:

O wie dank ich, daß gegeben

Solche Schmerzen mir Natur!

Lied 5: Träume

Sag, welch wunderbare Träume

Halten meinen Sinn umfangen,

Daß sie nicht wie leere Schäume

Sind in ödes Nichts vergangen?

Träume, die in jeder Stunde,

Jedem Tage schöner blühn,

Und mit ihrer Himmelskunde

Selig durchs Gemüte ziehn!

Träume, die wie hehre Strahlen

In die Seele sich versenken,

Dort ein ewig Bild zu malen:

Allvergessen, Eingedenken!

Träume, wie wenn Frühlingssonne

Aus dem Schnee die Blüten küßt,

Daß zu nie geahnter Wonne

Sie der neue Tag begrüßt,

Daß sie wachsen, daß sie blühen,

Träumed spenden ihren Duft,

Sanft an deiner Brust verglühen,

Und dann sinken in die Gruft.

(1857-1858 Von Wagner komponiert)

Mathilde Wesendonck poetry

Poem of the week June 20, 2010

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Archive W-X

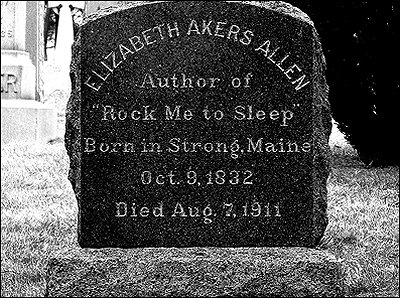

Elizabeth Akers Allen

(1832-1911)

Rock Me to Sleep

Backward, turn backward, O Time, in your flight,

Make me a child again just for tonight!

Mother, come back from the echoless shore,

Take me again to your heart as of yore;

Kiss from my forehead the furrows of care,

Smooth the few silver threads out of my hair;

Over my slumbers your loving watch keep;—

Rock me to sleep, mother, – rock me to sleep!

Backward, flow backward, O tide of the years!

I am so weary of toil and of tears,—

Toil without recompense, tears all in vain,—

Take them, and give me my childhood again!

I have grown weary of dust and decay,—

Weary of flinging my soul-wealth away;

Weary of sowing for others to reap;—

Rock me to sleep, mother – rock me to sleep!

Tired of the hollow, the base, the untrue,

Mother, O mother, my heart calls for you!

Many a summer the grass has grown green,

Blossomed and faded, our faces between:

Yet, with strong yearning and passionate pain,

Long I tonight for your presence again.

Come from the silence so long and so deep;—

Rock me to sleep, mother, – rock me to sleep!

Over my heart, in the days that are flown,

No love like mother-love ever has shone;

No other worship abides and endures,—

Faithful, unselfish, and patient like yours:

None like a mother can charm away pain

From the sick soul and the world-weary brain.

Slumber’s soft calms o’er my heavy lids creep;—

Rock me to sleep, mother, – rock me to sleep!

Come, let your brown hair, just lighted with gold,

Fall on your shoulders again as of old;

Let it drop over my forehead tonight,

Shading my faint eyes away from the light;

For with its sunny-edged shadows once more

Haply will throng the sweet visions of yore;

Lovingly, softly, its bright billows sweep;—

Rock me to sleep, mother, – rock me to sleep!

Mother, dear mother, the years have been long

Since I last listened your lullaby song:

Sing, then, and unto my soul it shall seem

Womanhood’s years have been only a dream.

Clasped to your heart in a loving embrace,

With your light lashes just sweeping my face,

Never hereafter to wake or to weep;—

Rock me to sleep, mother, – rock me to sleep!

Elizabeth Akers Allen poetry

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Archive A-B

.jpg)

William Blake

(1757-1827)

To Autumn

O Autumn, laden with fruit, and stainèd

With the blood of the grape, pass not, but sit

Beneath my shady roof; there thou may’st rest,

And tune thy jolly voice to my fresh pipe,

And all the daughters of the year shall dance!

Sing now the lusty song of fruits and flowers.

`The narrow bud opens her beauties to

The sun, and love runs in her thrilling veins;

Blossoms hang round the brows of Morning, and

Flourish down the bright cheek of modest Eve,

Till clust’ring Summer breaks forth into singing,

And feather’d clouds strew flowers round her head.

`The spirits of the air live on the smells

Of fruit; and Joy, with pinions light, roves round

The gardens, or sits singing in the trees.’

Thus sang the jolly Autumn as he sat;

Then rose, girded himself, and o’er the bleak

Hills fled from our sight; but left his golden load.

Ton van Kempen photos: Autumn 4

W. Blake poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: 4SEASONS#Autumn, Archive A-B, Archive A-B, Blake, William, Ton van Kempen Photos

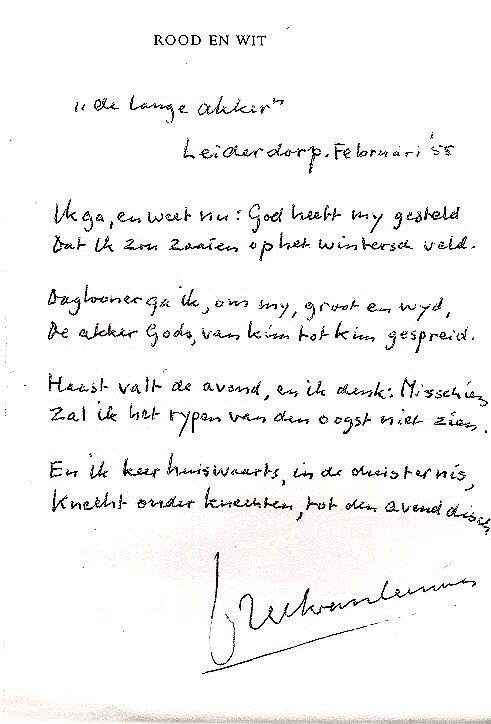

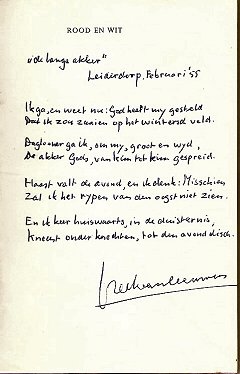

Jan Gielkens

Handgeschreven

Hoe bijzonder is een handgeschreven gedicht

van de minor poet Freek van Leeuwen?

In 1984 ruimde ik de bibliotheek op van de in dat jaar overleden Scandinaviste en vertaalster Saskia Ferwerda. Ze had een huis vol boeken, de helft ervan had betrekking op haar specialisme. Deze Scandinavische bibliotheek werd door de familie geschonken aan de universiteitsbibliotheek in Utrecht, maar die zat met de boeken in haar maag. De boeken belandden in de kelder van een pand aan het Lucas Bolwerk en bleven daar totdat dat pand een andere bestemming kreeg en leeg moest.

Niemand bleek zich voor de boeken verantwoordelijk te voelen en ze belandden in een container, waar ze in brand werden gestoken. De rest van de boeken had een beter lot: ze werden verkocht om er een Scandinavisch boekenreeksje van te financieren, en dat gebeurde tot het geld op was. Uit de niet-Scandinavische bibliotheek schonk ik later een aantal boeken met opdracht aan het Letterkundig Museum, zoals een bundel van Benno Barnard, die in Utrecht de buurjongen van Saskia Ferwerda was geweest. Gesigneerde bundels, brieven en Sinterklaasgedichten van de nu vergeten christelijke dichteres Tony de Ridder zaten er ook bij, net als een briefkaartje van Nobelprijswinnares Selma Lagerlöf, bij wie Saskia Ferwerda in Zweden op bezoek was geweest.

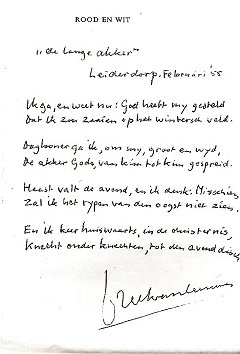

Een van de gesigneerde bundels was van de minor poet Freek van Leeuwen (1905-1968), die via de sociaaldemocratie bij het schrijverscollectief Links Richten terecht was gekomen en die later naar zijn christelijke roots zou terugkeren. Bij Van Leeuwens vijftigste verjaardag in februari 1955 verscheen bij De Beuk in Amsterdam de poëziebundel Rood en wit, een bloemlezing uit oud en nieuw werk onder redactie van Wim J. Simons. Op het schutblad van het exemplaar van Saskia Ferwerda stond een handgeschreven gedicht:

In 2002 vond ik bij De Slegte in Den Haag nog een exemplaar van Rood en wit, en op het schutblad stond een handgeschreven gedicht van de auteur. Het was hetzelfde gedicht als in de bundel van Saskia Ferwerda, zo herinnerde ik me, dus ik dacht: het LM heeft mijn cadeau verpatst. Ik dus een misschien wat al te boos briefje naar het LM gestuurd, waarop toenmalig directeur Anton Korteweg netjes en per omgaande antwoordde met de mededeling dat het boek dat ik indertijd had geschonken gewoon in de collectie van het museum zat. Een meegestuurde fotokopie bewees dat. Maar die kopie bewees ook dat mijn gedachte helemaal niet zo vreemd was:

.jpg)

En nu, nu ik over deze curieuze zaak wil schrijven, kijk ik eens wat rond op internet en vind er nog een: bij antiquariaat Fokas Holthuis in Den Haag:

Hoeveel van dit soort exemplaren zou Freek van Leeuwen hebben zitten pennen met zijn ballpoint?

Jan Gielkens over bibliofiele vondsten en typografische bijzonderheden

Eerder gepubliceerd op:www.teksteditie.org

kempis poetry magazine

More in: - Book Stories, Archive K-L, Jan Gielkens

.jpg)

Giacomo Leopardi

(1798-1837)

All’Italia

O patria mia, vedo le mura e gli archi

E le colonne e i simulacri e l’erme

Torri degli avi nostri,

Ma la gloria non vedo,

Non vedo il lauro e il ferro ond’eran carchi

I nostri padri antichi. Or fatta inerme,

Nuda la fronte e nudo il petto mostri.

Oimè quante ferite,

Che lividor, che sangue! oh qual ti veggio,

Formosissima donna! Io chiedo al cielo

E al mondo: dite dite;

Chi la ridusse a tale? E questo è peggio,

Che di catene ha carche ambe le braccia;

Sì che sparte le chiome e senza velo

Siede in terra negletta e sconsolata,

Nascondendo la faccia

Tra le ginocchia, e piange.

Piangi, che ben hai donde, Italia mia,

Le genti a vincer nata

E nella fausta sorte e nella ria.

Se fosser gli occhi tuoi due fonti vive,

Mai non potrebbe il pianto

Adeguarsi al tuo danno ed allo scorno;

Che fosti donna, or sei povera ancella.

Chi di te parla o scrive,

Che, rimembrando il tuo passato vanto,

Non dica: già fu grande, or non è quella?

Perchè, perchè? dov’è la forza antica,

Dove l’armi e il valore e la costanza?

Chi ti discinse il brando?

Chi ti tradì? qual arte o qual fatica

O qual tanta possanza

Valse a spogliarti il manto e l’auree bende?

Come cadesti o quando

Da tanta altezza in così basso loco?

Nessun pugna per te? non ti difende

Nessun de’ tuoi? L’armi, qua l’armi: io solo

Combatterò, procomberò sol io.

Dammi, o ciel, che sia foco

Agl’italici petti il sangue mio.

Dove sono i tuoi figli? Odo suon d’armi

E di carri e di voci e di timballi:

In estranie contrade

Pugnano i tuoi figliuoli.

Attendi, Italia, attendi. Io veggio, o parmi,

Un fluttuar di fanti e di cavalli,

E fumo e polve, e luccicar di spade

Come tra nebbia lampi.

Nè ti conforti? e i tremebondi lumi

Piegar non soffri al dubitoso evento?

A che pugna in quei campi

L’itala gioventude? O numi, o numi:

Pugnan per altra terra itali acciari.

Oh misero colui che in guerra è spento,

Non per li patrii lidi e per la pia

Consorte e i figli cari,

Ma da nemici altrui

Per altra gente, e non può dir morendo:

Alma terra natia,

La vita che mi desti ecco ti rendo.

Oh venturose e care e benedette

L’antiche età, che a morte

Per la patria correan le genti a squadre;

E voi sempre onorate e gloriose,

O tessaliche strette,

Dove la Persia e il fato assai men forte

Fu di poch’alme franche e generose!

Io credo che le piante e i sassi e l’onda

E le montagne vostre al passeggere

Con indistinta voce

Narrin siccome tutta quella sponda

Coprìr le invitte schiere

De’ corpi ch’alla Grecia eran devoti.

Allor, vile e feroce,

Serse per l’Ellesponto si fuggia,

Fatto ludibrio agli ultimi nepoti;

E sul colle d’Antela, ove morendo

Si sottrasse da morte il santo stuolo,

Simonide salia,

Guardando l’etra e la marina e il suolo.

E di lacrime sparso ambe le guance,

E il petto ansante, e vacillante il piede,

Toglieasi in man la lira:

Beatissimi voi,

Ch’offriste il petto alle nemiche lance

Per amor di costei ch’al Sol vi diede;

Voi che la Grecia cole, e il mondo ammira.

Nell’armi e ne’ perigli

Qual tanto amor le giovanette menti,

Qual nell’acerbo fato amor vi trasse?

Come sì lieta, o figli,

L’ora estrema vi parve, onde ridenti

Correste al passo lacrimoso e duro?

Parea ch’a danza e non a morte andasse

Ciascun de’ vostri, o a splendido convito:

Ma v’attendea lo scuro

Tartaro, e l’onda morta;

Nè le spose vi foro o i figli accanto

Quando su l’aspro lito

Senza baci moriste e senza pianto.

Ma non senza de’ Persi orrida pena

Ed immortale angoscia.

Come lion di tori entro una mandra

Or salta a quello in tergo e sì gli scava

Con le zanne la schiena,

Or questo fianco addenta or quella coscia;

Tal fra le Perse torme infuriava

L’ira de’ greci petti e la virtute.

Ve’ cavalli supini e cavalieri;

Vedi intralciare ai vinti

La fuga i carri e le tende cadute,

E correr fra’ primieri

Pallido e scapigliato esso tiranno;

Ve’ come infusi e tinti

Del barbarico sangue i greci eroi,

Cagione ai Persi d’infinito affanno,

A poco a poco vinti dalle piaghe,

L’un sopra l’altro cade. Oh viva, oh viva:

Beatissimi voi

Mentre nel mondo si favelli o scriva.

Prima divelte, in mar precipitando,

Spente nell’imo strideran le stelle,

Che la memoria e il vostro

Amor trascorra o scemi.

La vostra tomba è un’ara; e qua mostrando

Verran le madri ai parvoli le belle

Orme del vostro sangue. Ecco io mi prostro,

O benedetti, al suolo,

E bacio questi sassi e queste zolle,

Che fien lodate e chiare eternamente

Dall’uno all’altro polo.

Deh foss’io pur con voi qui sotto, e molle

Fosse del sangue mio quest’alma terra.

Che se il fato è diverso, e non consente

Ch’io per la Grecia i moribondi lumi

Chiuda prostrato in guerra,

Così la vereconda

Fama del vostro vate appo i futuri

Possa, volendo i numi,

Tanto durar quanto la vostra duri.

(1818)

![]()

Giacomo Leopardi poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

![]()

More in: Leopardi, Giacomo

.jpg)

C h a r l e s C r o s

(1842-1888)

Ballade des mauvaises personnes

Qu’on vive dans les étincelles

Ou qu’on dorme sur le gazon

Au bruit des râteaux et des pelles,

On entend mâles et femelles

Prêtes à toute trahison,

Les personnes perpétuelles

Aiguisant leurs griffes cruelles,

Les personnes qui ont raison.

Elles rêvent (choses nouvelles !)

Le pistolet et le poison.

Elles ont des chants de crécelles

Elles n’ont rien dans leurs cervelles

Ni dans le coeur aucun tison,

Froissant les fleurs sous leurs semelles

Et courant des routes (lesquelles ?)

Les personnes qui ont raison.

Malgré tant d’injures mortelles

Les roses poussent à foison

Et les seins gonflent les dentelles

Et rose est encor l’horizon ;

Roses sont Marie et Suzon !

Mais, les autres, que veulent-elles ?

Elles ne sont vraiment pas belles,

Les personnes qui ont raison.

ENVOI

Prince, qui, gracieux, excelles

A nous tirer de la prison,

Chasse au loin par tes ritournelles

Les personnes qui ont raison.

.jpg)

Charles Cros poetry

kempis poetry magazine

![]()

More in: Cros, Charles

Alfonsina Storni

(1892-1938)

¿Qué Diría?

¿Qué diría la gente, recortada y vacía,

Si un día fortuito, por ultra fantasía,

Me tiñera el cabello de plateado y violeta,

Usara peplo griego, cambiara la peineta

Por cintillo de flores: miosotis o jazmines,

Cantara por las calles al compás de violines,

O dijera mis versos recorriendo las plazas

Libertado mi gusto de vulgares mordazas?

¿Irían a mirarme cubriendo las aceras?

¿Me quemarían como quemaron heciceras?

¿Campanas tocarían para llamar a misa?

En verdad que pensarlo me da un poco de risa.

![]()

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Storni, Alfonsina

J.A. dèr Mouw

(1863-1919)

‘k Zie nu al hoe ‘k, als jij gestorven bent

‘K zie nu al hoe ‘k, als jij gestorven bent,

Zal zitten, kijkend naar je stil gezicht;

Wel vol verleden, toch pijnlijk verlicht,

Dat jij ten minste geen verdriet meer kent.

Mijn handen zullen, vroeger lang gewend,

Van zelf aaien je haar, waar levend ligt,

Als vroeger, nog het diep glanzende licht,

Dat uit de dood mij jouw vergeving zendt.

‘T is alles tevergeefs: nu weet ik al,

Dat ‘k dan, mijn hartje, niet begrijpen zal,

Hoe ‘k jou geen liefde gaf, mijzelf geen rust;

Zelfkwellend zal ‘k je, herrezen, zien staan,

Jong, als toen ik ‘t geluk voorbij liet gaan,

Die ene nacht. toen ‘k je niet heb gekust.

J.A. dèr Mouw gedicht

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Archive M-N

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature