Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

Berchtesgaden

Deze stilte tussen bergen maakte ik niet

eerder mee dan nu. Knielend naar het luchtledig

vergezicht van dat verre vroeger vermoed ik

in de wouden duistere geheimen. Met de geur

van amandel, van kerosine ook. Kijk ze toch

opstijgen als statige, o zo trage zeppelins.

“Nieuwe wegen zijn nooit weg”, liggen tegen

lome hellingen stoffige paden te overwegen.

Het aanzicht is craquelé. Dat moet ik schrijven.

Avonden zwijgen hier in vol ornaat, als priesters

in lege kerken. Tegen de lucht hangen koppels

kraaien, er zijn er veel, de grote zwarte vogel uit.

Bert Bevers

uit Afglans, Uitgeverij WEL, Bergen op Zoom, 1997

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Bevers, Bert

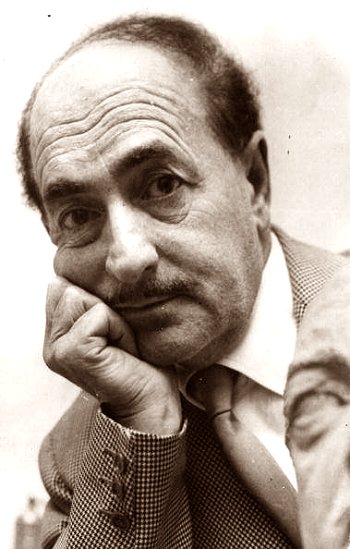

Salvatore Quasimodo

(1901-1968)

Street in Agrigentum

There is still the wind that I remember

firing the manes of horses, racing,

slanting, across the plains,

the wind that stains and scours the sandstone,

and the heart of gloomy columns, telamons,

overthrown in the grass. Spirit of the ancients, grey

with rancour, return on the wind,

breathe in that feather-light moss

that covers those giants, hurled down by heaven.

How alone in the space that’s still yours!

And greater, your pain, if you hear, once more,

the sound that moves, far off, towards the sea,

where Hesperus streaks the sky with morning:

the jew’s-harp vibrates

in the waggoner’s mouth

as he climbs the hill of moonlight, slow,

in the murmur of Saracen olive trees.

Salvatore Quasimodo poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive Q-R

Ton van Reen

Jef van Kempen houdt van gedichten

Jef van Kempen houdt van gedichten.

Hoe is dat zo gekomen?

Lang geleden las Jef het gedicht DE MUS van Jan Hanlo. Hij las en beluisterde het goed.

Hij hoorde dit:

DE MUS

Tjielp tjielp

tjielp tjielp tjielp

tjielp tjielp tjielp

tjielp tjielp

tjielp tjielp tjielp tjielp tjielp

tjielp tjielp tjielp

tjielp

etcetera.

Let op: het woord ETCETERA hoort bij het gedicht.

Dit etcetera betekent: eindeloos. Het gedicht DE MUS is dus een eeuwigdurend gedicht, dat overgaat van mus op mus.

Toen Jef het gedicht driemaal had gehoord, besloot hij vooral een vervolg te geven aan het laatste woord van het gedicht: etcetera.

Hij schafte vogeltjes aan om ten eeuwigen dage het gedicht van Jan rond te horen zingen.

Dat is nou eens een lesje leren uit de literatuur.

Etcetera, met een mensenleven lang durend vervolg op het getjielp.

Toevallig ben ik erachter gekomen waarom Jan Hanlo dit gedicht schreef.

In de donkere jaren van de wederopbouw na de oorlog gaf Jan les in de Engelse taal aan het instituut Schoevers voor aankomende secretaresses. En als het zo uitkwam gaf hij ook les in boekhouden.

Nu denken veel mensen dat zo’n bestaan voor een dichter vreemd is, maar het karakter van Jan Hanlo een beetje kennend, ik heb hem vaak meegemaakt, begrijp ik heel goed dat hij als dichter het dichtst bij zichzelf was als hij zijn kop vrij had in gebondenheid. De baan als leraar Engels en boekhouden beviel hem, omdat het zo absurd was. Tegen mijn achterneef Peter van Reen, illustrator en tekenaar bij de krant Het Volk, met wie hij bevriend was, zei hij dat alleen structuur het leven zinvol maakte.

Ten tijde van zijn gevangenschap in de klas en de leerlingen debet en credit leerde, moet hij ook naar buiten hebben verlangd. Vaak moet hij mussen aan het schoolraam hebben horen tjielpen en dat moet een zeker verlangen naar vrijheid hebben opgeroepen.

Terwijl hij de leerlingen sommen liet maken, luisterde hij naar de mus en, altijd op zoek naar structuur, zocht hij naar de structuur van het getjielp van het levenslied van de mus op de vensterbank van het klaslokaal.

Hij noteerde de klanken en hoorde zeven varianten, die eindeloos herhaald werden. Dat bracht hem ertoe het woord etcetera toe te voegen aan het klankgedicht over de mus.

Hij was blij, want hij had de structuur betrapt in het gezang van de mus.

Het bleek hem dat de mus niet zomaar wat zong, maar zichzelf oneindig bleef herhalen. Die eeuwige herhaling vatte hij samen in het woord etcetera.

Nu denken velen dat Jan Hanlo een liefhebber van vogels was. Dat was niet zo.

Als hij tijdens zijn lessen aan het Schoeversinstituut, naar buiten kijkend een kraai op een grasveld zou hebben gezien, had hij mogelijk het volgende gedicht geschreven:

Ka ka ka, kaka, krrr krrr , ka

krrr ka, ka krrr,

ka ka ka ka, krrrr , ka ka

krrr krrr krrr, ka

kaka, kaka, krrr, kaka, ka

kakaka, krrr ka, kakakaka, ka

ka

etcetera

Jef, die in de loop der jaren heeft geleerd om met vogels te praten zou dit gedicht als volgt hebben vertaald:

Wat doet die hond op ons grasveld

hij jaagt ons weg, die hond hoort hier niet

wat doet die hond, jaag hem weg

jaag hem de bomen in

die hond hoort hier niet, het gras is van ons

jaag hem de bomen in

wat doet die hond op ons gras

jaag hem weg

jaag hem de bomen in.

wat doet die hond op ons grasveld

wat?

etcetera

Zo is dus niet de kraai maar de mus heel toevallig in de Nederlandse literatuur terechtgekomen, maar had voor hetzelfde geld een kraai het onderwerp van een beroemd gedicht kunnen worden. Het had niet uitgemaakt. Het gedicht blijkt vooral bekend te zijn gebleven door het woord etcetera. Het ging Jan Hanlo in deze alleen om het woord etcetera. Heel tevreden schreef hij dat op, omdat hij de structuur van het vogelliedje had gevonden en hij begreep dat het gedicht eindeloos zou blijken te zijn.

Waarom was Hanlo zo uit op structuur? Waarom dwong hij zichzelf om alles wat hij deed gestructureerd aan te pakken? Tijdens mijn bezoeken aan Hanlo in het poorthuisje in Valkenburg, waar hij woonde in een eenkamervertrek, heb ik dat ontdekt. Hij legde zichzelf structuur op omdat hij geheel ongestructureerd was. En elke keer was hij blij om te ontdekken hoe anderen, in dit geval een mus, structuur aanbrachten in hun leven. Dat was ook de reden waarom hij in een piepklein huisje woonde. Een huis met meerdere vertrekken kon hij niet aan. Hij moest altijd alles onder handbereik hebben. Dat er zich spullen in andere vertrekken zouden bevinden, spullen die hij niet kon zien, was te veel van hem gevraagd.

Door zijn altijddurende jacht naar structuur beperkte hij zijn omgeving tot een steeds kleinere woonomgeving. In dat eenkamerwoninkje moest alles aanwezig zijn. Ook zijn motor.

Een andere reden om structuur aan te brengen was zijn armoe. Hij was zo arm als een rat. Wel beroemd in kleine kring, maar al heel lang zonder werk en af en toe vijf gulden vangend voor een gedicht in een literair tijdschrift. Het Fonds voor de Letteren bestond nog niet. Armoe dwong hem om heel gestructureerd met zijn geld om te gaan.

Waarom deze inleiding over Jan Hanlo als ik praat over het werk van Jef van Kempen?

Er moeten enkele dingen worden rechtgezet.

Jefs lievelingsgedicht is het gedicht De Mus van Jan Hanlo. Maar Jef heeft altijd gedacht dat Jan het gedicht heeft geschreven uit liefde voor de mus.

Niets is minder waar. Zaten er mussen op de vensterbank van zijn woninkje, dan joeg hij ze weg met een nijdig getik tegen het raam.

Het was Jan enkel en alleen te doen om het woord ETCETERA.

Herhaling van altijd hetzelfde: dat was structuur, dat was de structuur die hij voor zichzelf zocht.

Jef hoorde bij het lezen van het gedicht DE MUS inderdaad een tjielpende mus. En dacht dat Hanlo door dat ETCETERA het getjielp van de mus oneindig had willen horen. Waardoor het Jefs lievelingsgedicht werd omdat hij zelf ook oneindig naar het zingen van vogeltjes wilde luisteren. Om het gedicht van Jan Hanlo eindeloos te kunnen horen, schafte hij vogeltjes aan en zette zijn kleine tuin vol met vogelkooien om eindeloos het gedicht DE MUS te kunnen horen.

Vinken, sijsjes, paradijsvogeltjes, ik heb geen idee hoe die vogeltjes allemaal heten, maar vanaf de ontdekking van het gedicht DE MUS werd en wordt er in de kleine tuin van Jef dag en nacht, ETCETERA, gezongen.

Dames en heren, de inspiratie van een dichter kan uit onverwachte bronnen komen.

Jef ging verder dan Jan Hanlo. Niet alleen de vogeltjes en hun gezang boeien Jef, hij luistert naar de taal die zijn vogeltjes zingen. Naar de tekst van het vogellied. Vaak zit hij uren voor het hok, met een blocnote op schoot, te luisteren en streepjes te zetten. De dichter Jef van Kempen is de notulist van vogelcomposities.

Jef heeft ontdekt dat de taal van de vogels ingewikkeld is, maar ook dat er een bepaalde ordening in zit die lijkt op poëzie.

Dat eenmaal ontdekt hebbende blijkt dat, nu zijn verzamelde gedichten verschijnen, de meeste van zijn gedichten zijn ontstaan uit de aanzetten die hij heeft gemaakt in zijn blocnote met aantekeningen van het vogelgefluit in zijn tuin.

Om die vogeltjesteksten voor mensen zichtbaar en hoorbaar te maken, heeft Jef er mensenwoorden bij gevonden, zoals bij het gedicht van de kraaien die de hond op hun grasveld de boom in willen jagen Jef weet de vogeltjesteksten te vertalen naar het menselijk oor.

In aanzet zijn dus al zijn gedichten een vertaling van vogeltjesgefluit.

Zo blijkt dat Jef een dichter is geworden door het eindeloze woord ETCETERA van Jan Hanlo, die met dat woord een gedicht met eeuwigheidswaarde schiep.

Blij door het vertalen van de vogelliedjes in gedichten, ging Jef op zoek naar vergelijkingsmateriaal. Hij ontdekte de ene na de andere dichter die, elk op een eigen manier, de taal van vogels, olifanten, zebra’s en andere spraakmakende dieren opving en bewerkte voor het menselijk oor.

Er ontstond een grote collectie poëzie in huize Van Kempen, tot de kasten ervan uitpuilden. Jef besloot de gedichten die hij in zo’n prachtige vertalingen uit de meest uiteenlopende talen vond, uit te venten naar anderen.

Kortom, hij wilde anderen deelgenoot maken van het ETCETERA van Jan Hanlo.

Zo ontstond zijn weblog KEMPIS.nl.

In alle talen van de wereld vind je op zijn weblog gedichten van poëten, die net als Hanlo op zoek zijn naar iets wat aanvankelijk niet te begrijpen is, maar door de vertaling of de hertaling van de dichter begrijpelijk wordt.

Hanlo, die van kind af aan verdwaald was in het bestaan, was op zoek naar structuur in zijn leven. Pierre Kemp, altijd in het zwart gekleed, was juist op zoek naar kleur ter compensatie van zijn zwart gemoed. Vinkenoog was op zoek naar de structuur van het telefoonboek, omdat hij met alle mensen in de wereld in gesprek wilde blijven. Rilke was altijd op zoek naar de geluiden van de liefde.

Elke dichter blijkt op zoek te zijn naar iets dat aanvankelijk voor hem geheimzinnig is en dat hij wil bewoorden, waardoor hij er vertrouwd mee raakt.

Zo is Jef de verklanker geworden van de vogeltjestaal, maar ook van de taal van zijn omgeving. En dat is, in de ruimste zin, de stad Tilburg.

Ik besluit met een gedicht uit de bundel van Jef dat hij ook zelf heeft terugvertaald naar de taal van de vogels:

LANDSCHAP

Duizend kraaien

in de oude berk

tekenen

de grijze lucht

Deze leegte

had ik

niet vermoed

En nu het gedicht zoals het door Jef aan de vogels wordt verteld:

Bliep bliep tjiep, rrrrr

tjielp tjielp piep

piep piep piep piep

tjielp piep piep

rrrrr rrrrr piep tjielp piep

pieppiep rrrrrrr

hiep hiep tjielp piep

pieppiep piep rrrrrrrr

piep

etcetera

Zo vertelt Jef in de in hem opkomende gedichten aan de Tilburgse vogeltjes. De vogeltjes die in zijn tuintje zitten, de vogeltjes in het struikgewas rond de Hasseltse Kapel, het vogeltje dat doorklinkt in het gefluit van een vrolijke student op de fiets op weg naar school.

Kortom, voor al het gezang en getjielp dat Tilburg heet.

Jef heeft goed naar Jan Hanlo geluisterd. Hij heeft goed naar de vogeltjes geluisterd.

Wie Jef door Tilburg ziet dwalen en hem vreemde klanken hoort uitstoten, moet niet denken dat hij gek geworden is. Hij communiceert met de vogels.

ETCETERA. En dat nog vele jaren.

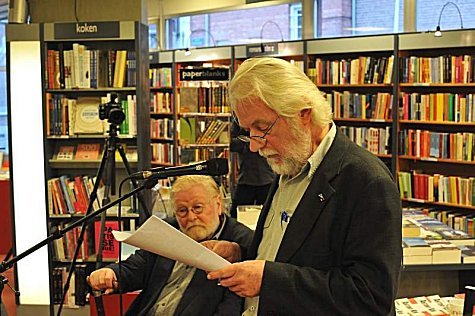

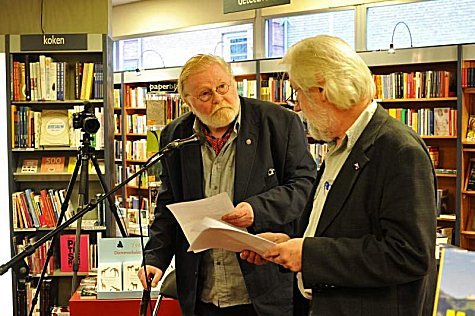

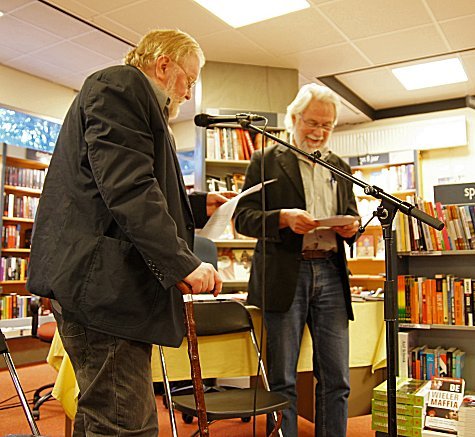

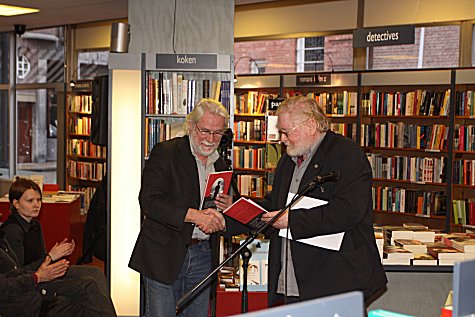

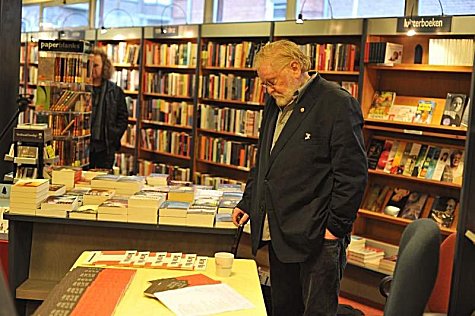

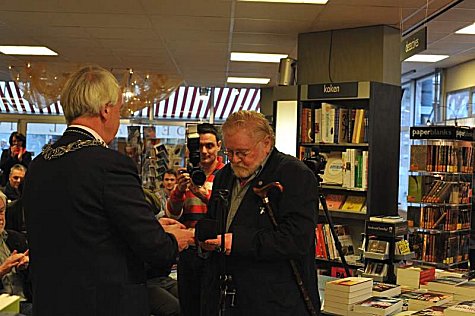

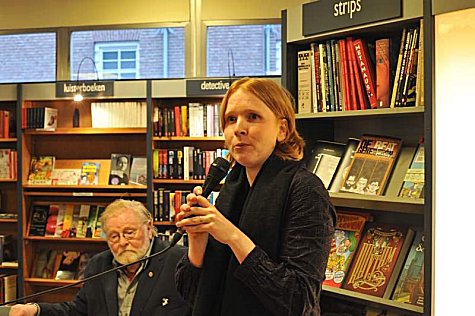

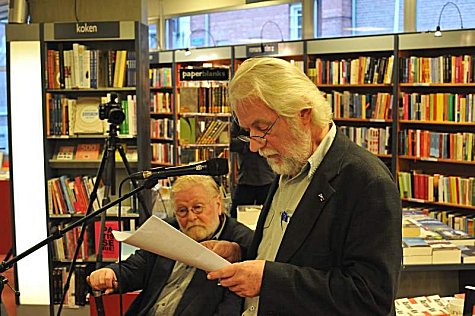

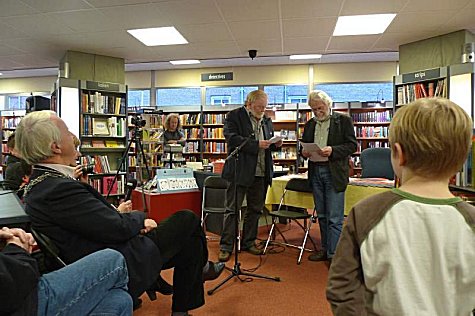

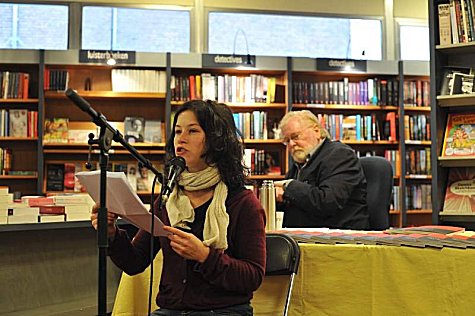

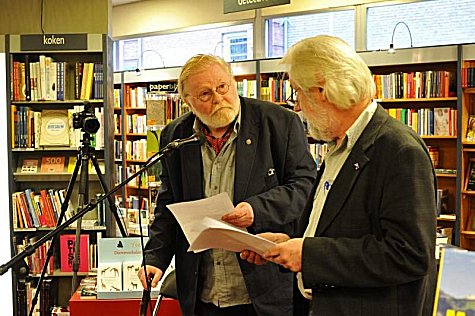

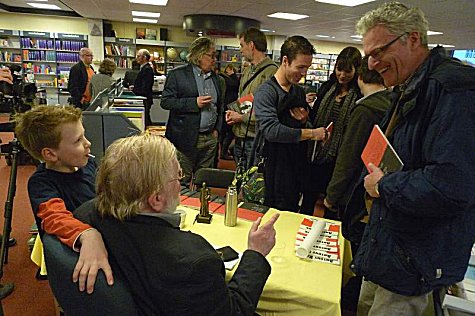

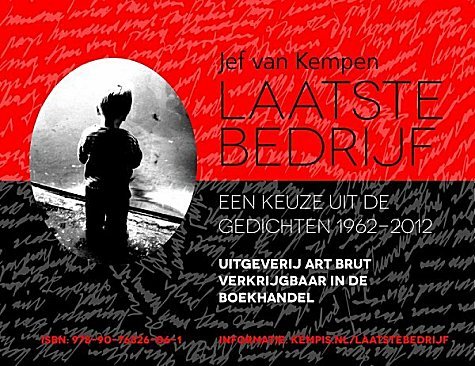

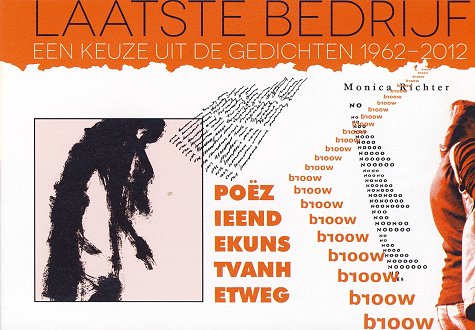

Op zondag 16 december 2012 vond in Boekhandel Livius in Tilburg de presentatie plaats van de nieuwe bundel van Jef van Kempen: Laatste bedrijf. Een keuze uit de gedichten 1962-2012. Op die bijeenkomst ontving Jef van Kempen uit handen van burgemeester Peter Noordanus de grote zilveren legpenning van de gemeente Tilburg voor zijn verdiensten op het gebied van literatuur en cultuur. Ton van Reen las zijn verhaal: ‘Jef van Kempen houdt van gedichten’ voor.

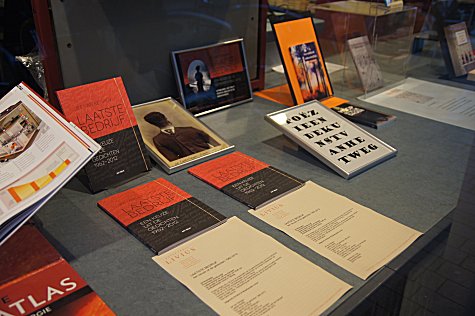

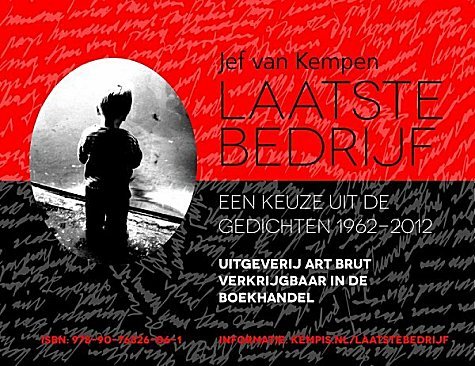

Jef van Kempen: Laatste Bedrijf. Een keuze uit de gedichten 1962-2012. Uitgeverij Art Brut – ISBN: 978-90-76326-06-1 / 68 pag. – 12,50 euro – geïllustreerd, 24×15 cm / Gedichten en illustraties van Jef van Kempen / Vormgeving Michiel Leenaars / In de bundel zijn tevens een aantal bijdragen opgenomen van Julia Origo, Monica Richter en J.A. Woolf.

Foto’s: Hans Hermans, Joep Eijkens, Peter IJsenbrant

fleursdumal.nl m a g a z i n e

More in: Jef van Kempen, Kempen, Jef van, Reen, Ton van, Reen, Ton van

Grote zilveren legpenning van de gemeente Tilburg voor de verdiensten van Jef van Kempen op het gebied van literatuur en cultuur

Jef van Kempen heeft op zondag 16 december 2012 een gemeentelijke onderscheiding ontvangen voor zijn jarenlange inzet voor het Tilburgse literaire en culturele leven. Hij kreeg de grote zilveren legpenning van de gemeente Tilburg uit handen van burgemeester Peter Noordanus. Dat gebeurde op 16 december in boekhandel Livius in Tilburg, tijdens de presentatie van de nieuwe bloemlezing uit de verzameld gedichten van Jef van Kempen.

Jef van Kempen is al sinds 1962 actief in het Brabantse, en meer bijzonder het Tilburgse literaire en culturele leven. Zijn loopbaan is bijzonder: veertig jaar lang werkte hij in de Tilburgse metaalsector. Daarnaast heeft hij bijzonder veel artikelen, gedichten, literair-historische essays, teksten en bundels uitgebracht. Zijn werk werd onder meer gepubliceerd in Brabant Cultureel, het Brabants Dagblad, Tilburg (tijdschrift voor geschiedenis, monumenten en cultuur), Actum Tilliburgis, Tilburg Magazine, Rijmtijd (tijdschrift Gezellestudie), DWB en De Parelduiker.

Veel van zijn artikelen gaan over in vergetelheid geraakte literair-historische figuren, zoals Dr. P.J. Cools, Henri Dolmans, Antony Kok en de schrijvers van de kunstbeweging en het gelijknamig tijdschrift De Stijl. Met zijn beschouwingen over de Tilburgse volkscultuur bereikte hij een breed en trouw lezerspubliek door alle lagen van de bevolking heen.

Sinds enige jaren is Jef van Kempen de drijvende kracht achter het online magazine KEMP=MAG (kempis.nl). Het is een van de meest bezochte poëziewebsites van Nederland en België. Veel bekende en onbekende dichters krijgen hier een podium voor hun werk. Het ondersteunen van onbekend en vaak nog jong talent is een van zijn andere bijzondere verdiensten. Al meer dan veertig jaar helpt Jef van Kempen hen om een plek te veroveren in de lokale of landelijke literaire wereld.

Van Kempen is één van de smaakmakers van de lokale cultuur. Zo helpt hij bij het organiseren van tentoonstellingen en symposia en was hij betrokken bij het opzetten van de grootste boekenmarkt van Zuid-Nederland in Tilburg. Verder was hij jarenlang bestuurslid van o.a. Amnesty International Nederland, Stichting Dr. P.J. Cools en de beheersstichting van de Hasseltse Kapel.

Jef van Kempen heeft met al deze werkzaamheden een bijzondere bijdrage aan de Tilburgse samenleving geleverd en doet dat nog steeds. Voor deze verdiensten krijgt hij de grote zilveren legpenning van de gemeente Tilburg.

(persbericht)

Op zondag 16 december 2012 vond in Boekhandel Livius in Tilburg de presentatie plaats van de nieuwe bundel van Jef van Kempen: ‘Laatste bedrijf. Een keuze uit de gedichten 1962-2012’. Op die bijeenkomst ontving Jef van Kempen uit handen van burgemeester Peter Noordanus de grote zilveren legpenning van de gemeente Tilburg voor zijn verdiensten op het gebied van literatuur en cultuur.

Verder las Ton van Reen zijn verhaal: ‘Jef van Kempen houdt van gedichten’ (morgen op deze website) en stadsdichter Esther Porcelijn droeg enkele gedichten en prozateksten van Jef van Kempen voor.

photos: joep eijkens

Jef van Kempen: Laatste Bedrijf. Een keuze uit de gedichten 1962-2012

Uitgeverij Art Brut – ISBN: 978-90-76326-06-1 / 68 pag. – 12,50 euro – geïllustreerd, 24×15 cm / Gedichten en illustraties van Jef van Kempen / Vormgeving Michiel Leenaars / In de bundel zijn tevens een aantal bijdragen opgenomen van Julia Origo, Monica Richter en J.A. Woolf.

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Jef van Kempen, Jef van Kempen Photos & Drawings, Kempen, Jef van

William Carlos Williams

(1883-1963)

This Is Just to Say

I have eaten

the plums

that were in

the icebox

and which

you were probably

saving

for breakfast

Forgive me

they were delicious

so sweet

and so cold

William Carlos Williams poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive W-X

A. E. Housman

(1859-1936)

Eight O’Clock

He stood, and heard the steeple

Sprinkle the quarters on the morning town.

One, two, three, four, to market-place and people

It tossed them down.

Strapped, noosed, nighing his hour,

He stood and counted them and cursed his luck;

And then the clock collected in the tower

Its strength, and struck.

A. E. Housman poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive G-H, Housman, A.E.

Jef van Kempen

LAATSTE BEDRIJF

een keuze uit de gedichten 1962-2012

Jef van Kempen (1948) publiceerde poëzie en korte verhalen, biografische artikelen en essays, o.a. over Guido Gezelle, J.-K. Huysmans, Theo van Doesburg, Antony Kok, de Stijlbeweging en Walter Breedveld. Hij is ook (mede)samensteller van enkele literaire bloemlezingen. Daarnaast schreef hij voor boeken, kranten en tijdschriften vele artikelen over de Brabantse geschiedenis. De serie artikelen die hij voor het Brabants Dagblad schreef over de straat waar hij geboren is, werden gebundeld onder de titel: Onze Lieve Vrouw van de Veestraat en andere verhalen en in het boek: Het gevoel dat je hier thuishoort. Jef van Kempen is ook actief als (literair) vertaler. Daarnaast is hij redacteur van kempis.nl (een veel bezochte internationale poëziewebsite) en drie andere literaire websites.

De bundel bevat, naast gepubliceerde en ongepubliceerde gedichten, talrijke illustraties van Jef van Kempen uit dezelfde periode.

Ter gelegenheid van het verschijnen van deze bundel ontving Jef van Kempen op 16 december 2012 van burgemeester Peter Noordanus de grote zilveren legpenning van de gemeente Tilburg voor zijn verdiensten op het gebied van literatuur en cultuur.

Jef van Kempen

Laatste Bedrijf.

Een keuze uit de gedichten 1962-2012

Uitgeverij Art Brut

ISBN: 978-90-76326-06-1

68 pag. – 12,50 euro

Geïllustreerd, 24×15 cm

Gedichten en illustraties van Jef van Kempen

Vormgeving Michiel Leenaars

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Jef van Kempen, Jef van Kempen Photos & Drawings, Kempen, Jef van

Amy Lowell

(1874-1925)

To a Friend

I ask but one thing of you, only one,

That always you will be my dream of you;

That never shall I wake to find untrue

All this I have believed and rested on,

Forever vanished, like a vision gone

Out into the night. Alas, how few

There are who strike in us a chord we knew

Existed, but so seldom heard its tone

We tremble at the half-forgotten sound.

The world is full of rude awakenings

And heaven-born castles shattered to the ground,

Yet still our human longing vainly clings

To a belief in beauty through all wrongs.

O stay your hand, and leave my heart its songs!

Amy Lowell poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive K-L, Archive K-L, Lowell, Amy

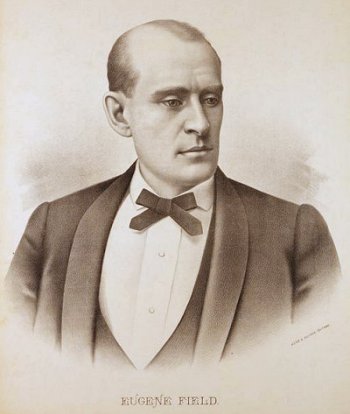

Eugene Field

(1850–1895)

Ballad of women i love

Prudence Mears hath an old blue plate

Hid away in an oaken chest,

And a Franklin platter of ancient date

Beareth Amandy Baker’s crest;

What times soever I’ve been their guest,

Says I to myself in an undertone:

“Of womenfolk, it must be confessed,

These do I love, and these alone.”

Well, again, in the Nutmeg State,

Dorothy Pratt is richly blest

With a relic of art and a land effete–

A pitcher of glass that’s cut, not pressed.

And a Washington teapot is possessed

Down in Pelham by Marthy Stone–

Think ye now that I say in jest

“These do I love, and these alone?”

Were Hepsy Higgins inclined to mate,

Or Dorcas Eastman prone to invest

In Cupid’s bonds, they could find their fate

In the bootless bard of Crockery Quest.

For they’ve heaps of trumpery–so have the rest

Of those spinsters whose ware I’d like to own;

You can see why I say with such certain zest,

“These do I love, and these alone.”

Eugene Field poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive E-F, Archive E-F, Field, Eugene

James Russell Lowell

(1819–1891)

A New Year’s Greeting

The century numbers fourscore years;

You, fortressed in your teens,

To Time’s alarums close your ears,

And, while he devastates your peers,

Conceive not what he means.

If e’er life’s winter fleck with snow

Your hair’s deep shadowed bowers,

That winsome head an art would know

To make it charm, and wear it so

As ’twere a wreath of flowers.

If to such fairies years must come,

May yours fall soft and slow

As, shaken by a bee’s low hum,

The rose-leaves waver, sweetly dumb,

Down to their mates below!

James Russell Lowell poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive K-L

![]()

Het vuurwerk

Een menigte trekt langs pubs en cafés,

doemt op in de condensramen van een hotel

in het licht van kroonluchters; een feest

slingert dansmuziek uit de ballroomzaal

de buitenlucht in, waar eiken majesteit

buigen om het marktplein en de patio;

het tafeltje waarop je hand ligt is krijt-

wit als je gezicht, dat zwijgt in crescendo.

Het is mooi geweest, de passie is bedaard, uit

je streling, die mijn rimpels bedde, is alle

geduld en zin geëbd, en van de weeromstuit

knielt de avond betraand bij je neer, vallen

je haren herfstig op je jas uiteen; de dracht

van je omslag. Bloeien boven jou wolken

pioenvormig op, neerdalend in roze gruis,

is het vuurwerk zonder ons begonnen,

schuifelt op straat het gedrang in een gelag,

verklankt, ergens, een schreeuw van diep binnenuit.

Niels Landstra

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive K-L, Landstra, Niels

Neerkomst

De dichter kuiert langs een haven. “Kijk”,

verplicht hij zich: de schepen die aankomen

zijn ver van de verlaten kade af. Komen ze

thuis of zijn ze halverwege het reizen? Hij weet

het niet. Schepen slapen als paarden, dat ziet

hij wel. Een onzichtbare zak haver voor de muil

hebben ze. Hun verzonnen vel trilt ongedurig

van nieuwsgierigheid naar al die verre einders.

Vermoeden van weemoed komt hem langs.

Langs pakhuizen maakt een meisje een radslag.

Niks tastend, voluit gaand. Hij prevelt wat

hij ziet: “Wat komt zij mooi neer.”

Bert Bevers

uit Afglans, Uitgeverij WEL, Bergen op Zoom, 1997

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Bevers, Bert

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature