Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

The Third Generation

The Third Generation

by Arthur Conan Doyle

Scudamore Lane, sloping down riverwards from just behind the Monument, lies at night in the shadow of two black and monstrous walls which loom high above the glimmer of the scattered gas lamps. The footpaths are narrow, and the causeway is paved with rounded cobblestones, so that the endless drays roar along it like breaking waves. A few old-fashioned houses lie scattered among the business premises, and in one of these, half-way down on the left-hand side, Dr. Horace Selby conducts his large practice. It is a singular street for so big a man; but a specialist who has an European reputation can afford to live where he likes. In his particular branch, too, patients do not always regard seclusion as a disadvantage.

It was only ten o’clock. The dull roar of the traffic which converged all day upon London Bridge had died away now to a mere confused murmur. It was raining heavily, and the gas shone dimly through the streaked and dripping glass, throwing little circles upon the glistening cobblestones. The air was full of the sounds of the rain, the thin swish of its fall, the heavier drip from the eaves, and the swirl and gurgle down the two steep gutters and through the sewer grating. There was only one figure in the whole length of Scudamore Lane. It was that of a man, and it stood outside the door of Dr. Horace Selby.

He had just rung and was waiting for an answer. The fanlight beat full upon the gleaming shoulders of his waterproof and upon his upturned features. It was a wan, sensitive, clear-cut face, with some subtle, nameless peculiarity in its expression, something of the startled horse in the white-rimmed eye, something too of the helpless child in the drawn cheek and the weakening of the lower lip. The man-servant knew the stranger as a patient at a bare glance at those frightened eyes. Such a look had been seen at that door many times before.

“Is the doctor in?”

The man hesitated.

“He has had a few friends to dinner, sir. He does not like to be disturbed outside his usual hours, sir.”

“Tell him that I MUST see him. Tell him that it is of the very first importance. Here is my card.” He fumbled with his trembling fingers in trying to draw one from his case. “Sir Francis Norton is the name. Tell him that Sir Francis Norton, of Deane Park, must see him without delay.”

“Yes, sir.” The butler closed his fingers upon the card and the half-sovereign which accompanied it. “Better hang your coat up here in the hall. It is very wet. Now if you will wait here in the consulting-room, I have no doubt that I shall be able to send the doctor in to you.”

It was a large and lofty room in which the young baronet found himself. The carpet was so soft and thick that his feet made no sound as he walked across it. The two gas jets were turned only half-way up, and the dim light with the faint aromatic smell which filled the air had a vaguely religious suggestion. He sat down in a shining leather armchair by the smouldering fire and looked gloomily about him. Two sides of the room were taken up with books, fat and sombre, with broad gold lettering upon their backs. Beside him was the high, old-fashioned mantelpiece of white marble—the top of it strewed with cotton wadding and bandages, graduated measures, and little bottles. There was one with a broad neck just above him containing bluestone, and another narrower one with what looked like the ruins of a broken pipestem and “Caustic” outside upon a red label. Thermometers, hypodermic syringes bistouries and spatulas were scattered about both on the mantelpiece and on the central table on either side of the sloping desk. On the same table, to the right, stood copies of the five books which Dr. Horace Selby had written upon the subject with which his name is peculiarly associated, while on the left, on the top of a red medical directory, lay a huge glass model of a human eye the size of a turnip, which opened down the centre to expose the lens and double chamber within.

Sir Francis Norton had never been remarkable for his powers of observation, and yet he found himself watching these trifles with the keenest attention. Even the corrosion of the cork of an acid bottle caught his eye, and he wondered that the doctor did not use glass stoppers. Tiny scratches where the light glinted off from the table, little stains upon the leather of the desk, chemical formulae scribbled upon the labels of the phials—nothing was too slight to arrest his attention. And his sense of hearing was equally alert. The heavy ticking of the solemn black clock above the mantelpiece struck quite painfully upon his ears. Yet in spite of it, and in spite also of the thick, old-fashioned wooden partition, he could hear voices of men talking in the next room, and could even catch scraps of their conversation. “Second hand was bound to take it.” “Why, you drew the last of them yourself!”

“How could I play the queen when I knew that the ace was against me?” The phrases came in little spurts falling back into the dull murmur of conversation. And then suddenly he heard the creaking of a door and a step in the hall, and knew with a tingling mixture of impatience and horror that the crisis of his life was at hand.

Dr. Horace Selby was a large, portly man with an imposing presence. His nose and chin were bold and pronounced, yet his features were puffy, a combination which would blend more freely with the wig and cravat of the early Georges than with the close-cropped hair and black frock-coat of the end of the nineteenth century. He was clean shaven, for his mouth was too good to cover—large, flexible, and sensitive, with a kindly human softening at either corner which with his brown sympathetic eyes had drawn out many a shame-struck sinner’s secret. Two masterful little bushy side-whiskers bristled out from under his ears spindling away upwards to merge in the thick curves of his brindled hair. To his patients there was something reassuring in the mere bulk and dignity of the man. A high and easy bearing in medicine as in war bears with it a hint of victories in the past, and a promise of others to come. Dr. Horace Selby’s face was a consolation, and so too were the large, white, soothing hands, one of which he held out to his visitor.

“I am sorry to have kept you waiting. It is a conflict of duties, you perceive—a host’s to his guests and an adviser’s to his patient. But now I am entirely at your disposal, Sir Francis. But dear me, you are very cold.”

“Yes, I am cold.”

“And you are trembling all over. Tut, tut, this will never do! This miserable night has chilled you. Perhaps some little stimulant——”

“No, thank you. I would really rather not. And it is not the night which has chilled me. I am frightened, doctor.”

The doctor half-turned in his chair, and he patted the arch of the young man’s knee, as he might the neck of a restless horse.

“What then?” he asked, looking over his shoulder at the pale face with the startled eyes.

Twice the young man parted his lips. Then he stooped with a sudden gesture, and turning up the right leg of his trousers he pulled down his sock and thrust forward his shin. The doctor made a clicking noise with his tongue as he glanced at it.

“Both legs?”

“No, only one.”

“Suddenly?”

“This morning.”

“Hum.”

The doctor pouted his lips, and drew his finger and thumb down the line of his chin. “Can you account for it?” he asked briskly.

“No.”

A trace of sternness came into the large brown eyes.

“I need not point out to you that unless the most absolute frankness——”

The patient sprang from his chair. “So help me God!” he cried, “I have nothing in my life with which to reproach myself. Do you think that I would be such a fool as to come here and tell you lies. Once for all, I have nothing to regret.” He was a pitiful, half-tragic and half-grotesque figure, as he stood with one trouser leg rolled to the knee, and that ever present horror still lurking in his eyes. A burst of merriment came from the card-players in the next room, and the two looked at each other in silence.

“Sit down,” said the doctor abruptly, “your assurance is quite sufficient.” He stooped and ran his finger down the line of the young man’s shin, raising it at one point. “Hum, serpiginous,” he murmured, shaking his head. “Any other symptoms?”

“My eyes have been a little weak.”

“Let me see your teeth.” He glanced at them, and again made the gentle, clicking sound of sympathy and disapprobation.

“Now your eye.” He lit a lamp at the patient’s elbow, and holding a small crystal lens to concentrate the light, he threw it obliquely upon the patient’s eye. As he did so a glow of pleasure came over his large expressive face, a flush of such enthusiasm as the botanist feels when he packs the rare plant into his tin knapsack, or the astronomer when the long-sought comet first swims into the field of his telescope.

“This is very typical—very typical indeed,” he murmured, turning to his desk and jotting down a few memoranda upon a sheet of paper. “Curiously enough, I am writing a monograph upon the subject. It is singular that you should have been able to furnish so well-marked a case.” He had so forgotten the patient in his symptom, that he had assumed an almost congratulatory air towards its possessor. He reverted to human sympathy again, as his patient asked for particulars.

“My dear sir, there is no occasion for us to go into strictly professional details together,” said he soothingly. “If, for example, I were to say that you have interstitial keratitis, how would you be the wiser? There are indications of a strumous diathesis. In broad terms, I may say that you have a constitutional and hereditary taint.”

The young baronet sank back in his chair, and his chin fell forwards upon his chest. The doctor sprang to a side-table and poured out half a glass of liqueur brandy which he held to his patient’s lips. A little fleck of colour came into his cheeks as he drank it down.

“Perhaps I spoke a little abruptly,” said the doctor, “but you must have known the nature of your complaint. Why, otherwise, should you have come to me?”

“God help me, I suspected it; but only today when my leg grew bad. My father had a leg like this.”

“It was from him, then——?”

“No, from my grandfather. You have heard of Sir Rupert Norton, the great Corinthian?”

The doctor was a man of wide reading with a retentive, memory. The name brought back instantly to him the remembrance of the sinister reputation of its owner—a notorious buck of the thirties—who had gambled and duelled and steeped himself in drink and debauchery, until even the vile set with whom he consorted had shrunk away from him in horror, and left him to a sinister old age with the barmaid wife whom he had married in some drunken frolic. As he looked at the young man still leaning back in the leather chair, there seemed for the instant to flicker up behind him some vague presentiment of that foul old dandy with his dangling seals, many-wreathed scarf, and dark satyric face. What was he now? An armful of bones in a mouldy box. But his deeds— they were living and rotting the blood in the veins of an innocent man.

“I see that you have heard of him,” said the young baronet. “He died horribly, I have been told; but not more horribly than he had lived. My father was his only son. He was a studious man, fond of books and canaries and the country; but his innocent life did not save him.”

“His symptoms were cutaneous, I understand.”

“He wore gloves in the house. That was the first thing I can remember. And then it was his throat. And then his legs. He used to ask me so often about my own health, and I thought him so fussy, for how could I tell what the meaning of it was. He was always watching me—always with a sidelong eye fixed upon me. Now, at last, I know what he was watching for.”

“Had you brothers or sisters?”

“None, thank God.”

“Well, well, it is a sad case, and very typical of many which come in my way. You are no lonely sufferer, Sir Francis. There are many thousands who bear the same cross as you do.”

“But where is the justice of it, doctor?” cried the young man, springing from his chair and pacing up and down the consulting-room. “If I were heir to my grandfather’s sins as well as to their results, I could understand it, but I am of my father’s type. I love all that is gentle and beautiful—music and poetry and art. The coarse and animal is abhorrent to me. Ask any of my friends and they would tell you that. And now that this vile, loathsome thing—ach, I am polluted to the marrow, soaked in abomination! And why? Haven’t I a right to ask why? Did I do it? Was it my fault? Could I help being born? And look at me now, blighted and blasted, just as life was at its sweetest. Talk about the sins of the father—how about the sins of the Creator?” He shook his two clinched hands in the air—the poor impotent atom with his pin-point of brain caught in the whirl of the infinite.

The doctor rose and placing his hands upon his shoulders he pressed him back into his chair once more. “There, there, my dear lad,” said he; “you must not excite yourself. You are trembling all over. Your nerves cannot stand it. We must take these great questions upon trust. What are we, after all? Half-evolved creatures in a transition stage, nearer perhaps to the Medusa on the one side than to perfected humanity on the other. With half a complete brain we can’t expect to understand the whole of a complete fact, can we, now? It is all very dim and dark, no doubt; but I think that Pope’s famous couplet sums up the whole matter, and from my heart, after fifty years of varied experience, I can say——”

But the young baronet gave a cry of impatience and disgust. “Words, words, words! You can sit comfortably there in your chair and say them—and think them too, no doubt. You’ve had your life, but I’ve never had mine. You’ve healthy blood in your veins; mine is putrid. And yet I am as innocent as you. What would words do for you if you were in this chair and I in that? Ah, it’s such a mockery and a make-believe! Don’t think me rude, though, doctor. I don’t mean to be that. I only say that it is impossible for you or any other man to realise it. But I’ve a question to ask you, doctor. It’s one on which my whole life must depend.” He writhed his fingers together in an agony of apprehension.

“Speak out, my dear sir. I have every sympathy with you.”

“Do you think—do you think the poison has spent itself on me? Do you think that if I had children they would suffer?”

“I can only give one answer to that. ‘The third and fourth generation,’ says the trite old text. You may in time eliminate it from your system, but many years must pass before you can think of marriage.”

“I am to be married on Tuesday,” whispered the patient.

It was the doctor’s turn to be thrilled with horror. There were not many situations which would yield such a sensation to his seasoned nerves. He sat in silence while the babble of the card-table broke in upon them again. “We had a double ruff if you had returned a heart.” “I was bound to clear the trumps.” They were hot and angry about it.

“How could you?” cried the doctor severely. “It was criminal.”

“You forget that I have only learned how I stand to-day.” He put his two hands to his temples and pressed them convulsively. “You are a man of the world, Dr. Selby. You have seen or heard of such things before. Give me some advice. I’m in your hands. It is all very sudden and horrible, and I don’t think I am strong enough to bear it.”

The doctor’s heavy brows thickened into two straight lines, and he bit his nails in perplexity.

“The marriage must not take place.”

“Then what am I to do?”

“At all costs it must not take place.”

“And I must give her up?”

“There can be no question about that.”

The young man took out a pocketbook and drew from it a small photograph, holding it out towards the doctor. The firm face softened as he looked at it.

“It is very hard on you, no doubt. I can appreciate it more now that I have seen that. But there is no alternative at all. You must give up all thought of it.”

“But this is madness, doctor—madness, I tell you. No, I won’t raise my voice. I forgot myself. But realise it, man. I am to be married on Tuesday. This coming Tuesday, you understand. And all the world knows it. How can I put such a public affront upon her. It would be monstrous.”

“None the less it must be done. My dear lad, there is no way out of it.”

“You would have me simply write brutally and break the engagement at the last moment without a reason. I tell you I couldn’t do it.”

“I had a patient once who found himself in a somewhat similar situation some years ago,” said the doctor thoughtfully. “His device was a singular one. He deliberately committed a penal offence, and so compelled the young lady’s people to withdraw their consent to the marriage.”

The young baronet shook his head. “My personal honour is as yet unstained,” said he. “I have little else left, but that, at least, I will preserve.”

“Well, well, it is a nice dilemma, and the choice lies with you.”

“Have you no other suggestion?”

“You don’t happen to have property in Australia?”

“None.”

“But you have capital?”

“Yes.”

“Then you could buy some. To-morrow morning would do. A thousand mining shares would be enough. Then you might write to say that urgent business affairs have compelled you to start at an hour’s notice to inspect your property. That would give you six months, at any rate.”

“Well, that would be possible. Yes, certainly, it would be possible. But think of her position. The house full of wedding presents—guests coming from a distance. It is awful. And you say that there is no alternative.”

The doctor shrugged his shoulders.

“Well, then, I might write it now, and start to-morrow—eh? Perhaps you would let me use your desk. Thank you. I am so sorry to keep you from your guests so long. But I won’t be a moment now.”

He wrote an abrupt note of a few lines. Then with a sudden impulse he tore it to shreds and flung it into the fireplace.

“No, I can’t sit down and tell her a lie, doctor,” he said rising. “We must find some other way out of this. I will think it over and let you know my decision. You must allow me to double your fee as I have taken such an unconscionable time. Now good-bye, and thank you a thousand times for your sympathy and advice.”

“Why, dear me, you haven’t even got your prescription yet. This is the mixture, and I should recommend one of these powders every morning, and the chemist will put all directions upon the ointment box. You are placed in a cruel situation, but I trust that these may be but passing clouds. When may I hope to hear from you again?”

“To-morrow morning.”

“Very good. How the rain is splashing in the street! You have your waterproof there. You will need it. Good-bye, then, until to-morrow.”

He opened the door. A gust of cold, damp air swept into the hall. And yet the doctor stood for a minute or more watching the lonely figure which passed slowly through the yellow splotches of the gas lamps, and into the broad bars of darkness between. It was but his own shadow which trailed up the wall as he passed the lights, and yet it looked to the doctor’s eye as though some huge and sombre figure walked by a manikin’s side and led him silently up the lonely street.

Dr. Horace Selby heard again of his patient next morning, and rather earlier than he had expected. A paragraph in the Daily News caused him to push away his breakfast untasted, and turned him sick and faint while he read it. “A Deplorable Accident,” it was headed, and it ran in this way:

“A fatal accident of a peculiarly painful character is reported from King William Street. About eleven o’clock last night a young man was observed while endeavouring to get out of the way of a hansom to slip and fall under the wheels of a heavy, two-horse dray. On being picked up his injuries were found to be of the most shocking character, and he expired while being conveyed to the hospital. An examination of his pocketbook and cardcase shows beyond any question that the deceased is none other than Sir Francis Norton, of Deane Park, who has only within the last year come into the baronetcy. The accident is made the more deplorable as the deceased, who was only just of age, was on the eve of being married to a young lady belonging to one of the oldest families in the South. With his wealth and his talents the ball of fortune was at his feet, and his many friends will be deeply grieved to know that his promising career has been cut short in so sudden and tragic a fashion.”

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (1859 – 1930)

Round the Red Lamp: Being Facts and Fancies of Medical Life

The Third Generation. (#04)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Doyle, Arthur Conan, Doyle, Arthur Conan, DRUGS & DISEASE & MEDICINE & LITERATURE, Round the Red Lamp

Op 9 Augustus sal dit presies vyfhonderd jaar wees dat die middeleeuse skilder Hieronymus Bosch oorlede is. Sy nalatenskap tel vierentwintig skilderye, twintig tekeninge en om nou maar ’n wilde sprong te maak: enkele Afrikaanse gedigte. Kenners kloof nogal hare oor die aantal skilderye en sketse. Versamelaars en museums se aansien en geld styg en val erger as op die aandelebeurs. Kontroversie en roem sorg daarvoor dat die 75 000 kaartjies wat gedruk is vir die tentoonstelling “Jheronimus Bosch – Visioenen van een genie” in ’s Hertogenbosch (Den Bosch) reeds uitverkoop is. Dié tentoonstelling duur tot 8 Mei. Op 31 Mei open die Nasionale Museum Prado in Madrid, met “Bosch – The Centenary Exhibition”.

As onderdeel van die vyfhonderd jaar vierings van Bosch se kunstenaarskap het sy Nederlandse geboortestad en die Noord-Brabants Museum saamgewerk om die Bosch Research and Conservation Project (BRCP) op te rig. Dit is hier waar wetenskap en kuns saamkom. En dít sorg vir beroering. Die BRCP is vyf jaar terug uit nood gestig om as ruilmiddel te dien vir soveel moontlik van Jeroen Bosch se oorspronklike werk met die oog op “ – Visioenen van een genie”. Daarvoor moes minstens museums soos die Prado, die Louvre in Parys en die National Art Gallery in London benader word. Dit was van die begin af duidelik dat Prado nie “De tuin der Lusten” – Bosch se meesterwerk – sou afstaan vir ´n tentoonstelling in Nederland of op enige ander plek nie. Te kwesbaar, was hulle verskoning. Bosch is eintlik ´n Spaanse skilder in hulle oë. Hulle noem hom El Bosco.

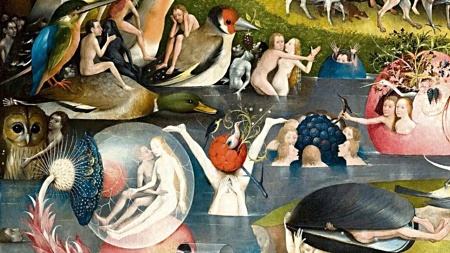

D.J. Opperman het gelukkig al in die bundel “Engel uit die klip” (1950) oor “De tuin der Lusten” geskryf en dit toeganklik gemaak vir Afrikaanse poësielesers, al het JEROEN BOSCH nooit so bekend geword soos “Draaikewers” en “Sproeireën” nie. Hy het die skildery as ’n onontkombaar bekoorlike nagmerrie beskryf. Vandag kan die detail van “De tuin der Lusten” op internet bestudeer word. Dan verstaan mens sommer baie beter Opperman se verwysings na “stekelige plante, voëls en mens” en “laat ons vlug uit die gebras / en skuil in mossel” en na “sweef in belle glas”. Hierdie aanhalings uit Opperman se gedig is almal bo-aan die artikel in ’n uitsnede van “Die tuin der Lusten” afgebeeld. Dis moeilik om ´n mens se oë daarvan los te skeur wanneer Bosch duiwelsadvokaat speel. Hy vra as kluisenaar en absolute eenling aandag vir die verval van morele waardes in sy tyd.

JEROEN BOSCH

Ydel is die wêreld, maar ydeler my gees,

wat om die dertig nagte in nagmerries

van stekelige plante, voëls en mens genees.

Uit ou en nuwe streke van die aarde kies

die duiwel al hoe lustiger vir my, vir jou,

vir die derduisende kostuum en mombakkies.

Dit trek stoete, kermis om die Kruis, wissel

van gedaante deur die eeue; maar die spel

bly steeds dieselfde in monnike, masjiene of dissel.

En ewig in die kringloop van die lus gevang

ry ons en kap die lieste van die hingste

om en om die kraaie op kaal vrouens in die dam.

Ag, Liefste! Kom dan, laat ons vlug uit die gebras

en skuil in mossel, horingpeul – en ver bokant

die kermis van die bose sweef in belle glas.

Want in my is die swaap, die visgelipte sot

wat elke toertjie van ’n towenaar befluit …

maar wonderwerke en Sy kruisiging bespot;

en, as ek God saam met Antonius aanroep,

is hy reeds daar wat van ’n nuwe geilte

roekeloos die eerste swaeltjies deur ’n tregter poep.

In strofe 4 fokus Opperman op die deel regs, skuins bokant die eerste gedetailleerde afbeelding. Dit word die Moredans genoem. Die dans vind plaas om die dam met die kaal vrouens en kraaie.

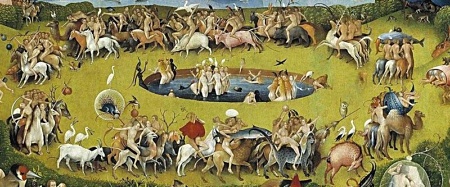

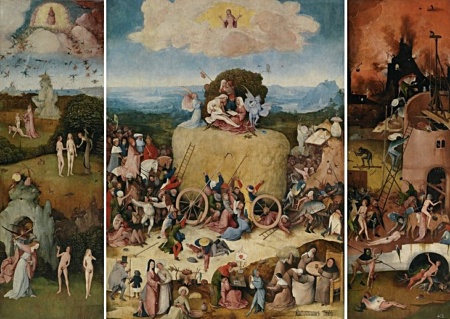

Bogenoemde twee afbeeldings is onderdele van die middelste paneel van “De tuin der Lusten”, wat eintlik ´n drieluik is. Die linkerkantste luik beeld die skepping van Adam en Eva uit. Die middelste luik beeld die aardse lewe as ´n tuin vol verleidings met eksotiese plante en diere, kaal mense, fabelagtige wesens en pienk fonteine uit. Dis hierdie luik wat die oorkoepelende naam “De tuin der Lusten” dra en waardeur Opperman verlei is om sy gedig JEROEN BOSCH te skryf. Die regterkantste luik beeld die hel uit. Die slotreël van die gedig verwys na ´n onderdeel uit die hel en word in die volgende afbeelding uitgebeeld.

Opperman se verwysing na Antonius roep die skildery “De verzoeking van de heilige Antonius” op. Dit is één van die werke wat ´n opskudding veroorsaak het. Die BRCP het ´n nuwe sisteem ontwikkel waarmee hulle die egtheid van al die Bosch-skilderye getoets het. Daarvolgens is “De verzoeking van de heilige Antonius” in Prado ´n vervalsing. Tegelykertyd het die BRCP het ook ´n egte skilderytjie uit 1500 – 1510 met dieselfde naam ontdek. Dit het in die Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City, Missouri, gehang, maar is nou op bruikleen in Den Bosch. Die BRCP het onder andere skildertegnieke vergelyk. Jeroen Bosch se handtekening is sigbaar gemaak met behulp van infrafrooi fotografie. Die Spanjaarde is woedend. Hulle het geweier om die bruikleenkontrak met die Noord-Brabantse Museum volledig uit te voer en twee skilderye teruggehou: “De verzoeking van de heilige Antonius” en “De Keisnijding”. Die twee weergawes van “De verzoeking van de heilige Antonius” verskil nogal. Hieronder is ´n afbeelding van die ontdekking in Missouri: net 38,6 by 25,1 sentimeter groot.

Gelukkig het Prado “De hooiwagen” (’n ander drieluik van Bosch) wél in bruikleen aan die Nederlandse museum toegestaan, maar ook hier was daar ´n slang in die gras. In plaas van om dit direk na die Noord-Brabantse Museum in Den Bosch toe te stuur, gaan maak “De hooiwagen” eers vir drie maande ´n draai in Museum Boijmans van Beuningen in Rotterdam! Dit het weer vir groot teleurstelling gesorg by die Noord-Brabants Museum, maar hulle hande was afgekap. Boijmans van Beuningen besit kosbaarder ruilware vir so ´n tipe transaksie as die BRCP.

Johan van Wyk se gedig oor “De hooiwagen” is in sy bundel “Deur die oog van die luiperd” (1976) gepubliseer. In hieronymus bosch se koringwa word die linkerkantste paneel in die eerste vyf strofes beskryf. Wat Van Wyk herkenbaar verwoord, is “die rebelse insekte swem in ’n boeg af” en ook “’n markvrou / tussen vrugtebome, God trou / adam en eva”.

Van Wyk gebruik aan die einde van strofe 2 ’n aanhaling van die relatief onbekende digter Gert Strydom. Dit is ’n intertekstuele standpunt in kontras met Breytenbach se beginreël “Dat pyn bestaan is onnodig Heer” uit breyten bid vir homself. Betrek Van Wyk ook in strofes 3 en 4 in die langer aanhaling vir Strydom? Of skryf hy eintlik die standpunt van Bosch neer wat die verdorwenheid van sy eie tyd uitbeeld in ewe verleidelike as bedreigende beelde? Wie is “God se raadgewer”? Waar die lang aanhaling met die eietydse opmerking “dis demokraties heer” vandaan kom, is onduidelik.

Net soos by “De tuin der Lusten” dra die middelste paneel die naam van die hele drieluik “De hooiwagen”. Op hierdie paneel begin Van Wyk se beskrywing regs onder by “die vet monnik” wat met ’n wynbeker in die hand sit en kyk na “die nonne wat die sakke… / vol koring maak”. Sentraal voor die koringwa in dié deel is ’n “broer wat sy broer keel- / af sny”. Eietyds interpreteer Van Wyk die karakters aan die linkerkant as “ministers met politieke kommentators” wat intertekstueel kan verwys na TT Cloete se gedig Behoefte aan ongunstige weers- en ander omstandighede. Ook die “vraatsugtiges wat onder die wiel omkom” en die “skare ongediertes” wat die koringwa in die hel in trek, is sigbaar op die middelste paneel.

hieronymus bosch se koringwa

die rebelse insekte swem in ’n boeg af

na die maagdrots, ’n markvrou

tussen vrugtebome, God trou

adam en eva, oproeriges word verban

na die aarde die paradys

terwyl hulle daal

kyk hulle met blitsende oë na die vrou, kaal

en dom, “dat pyn bestaan is nodig heer”

byt God se raadgewer hom in die oor,

“mag ons hulle kennis gee

dis demokraties heer, mag hulle naak

mekaar se vrugte aanraak

en vinnig die drif probeer toemaak met bak

hande, blare en lap, mag hulle pyn

hê, heer, en mag hulle inmekaar saak

in die stof, straf ons so, heer”

die hartseer engel met die swaard

jaag hulle uit, nog met skrik en slaap

in die oë, so het dit gekom dat almal loop

agter die koringwa: die nonne wat die sakke van die vet monnik

vol koring maak, ’n broer wat sy broer keel-

af sny, ministers met politieke kommentators

wat betaamlik volg en vraatsugtiges wat onder die wiele omkom

’n skare ongediertes leitrek die mensdom na die hel

dit is elke mens vir homself, met homself

selfs seks is net vir self, die wederhelf

word in die liefdestransaksie ingedans

en “ena gee raad” psigosofeer oor wat

ons moet maak met probleme

elke heerser is ’n antichris wat omsien

na sy mense se belange en sorg dat die wa van onenigheid

nie uit sig raak nie, en niemand

behalwe ’n engel kyk op na God

op ’n wolk bo al die gewoel, in die hel

is elkeen bang hy word nie meer verkrag of gemartel nie

want, dat pyn bestaan is nodig

Ook ander Afrikaanse digters soos W.E.G. Louw het oor Jeroen Bosch se werk geskryf.

Dat digters vandag nog in die ban van Bosch se skilderye nuwe gedigte skryf, is te verstane as mens na al hierdie afbeeldings kyk. Digters laat hulle bewustelik of onbewustelik verlei. ’n Gedig van ’n stadsgenoot wat verlede jaar op die tafel beland het by die “Literaire Salon in’t Wevershuisje”, is nié geskryf na aanleiding van ’n skildery van Bosch nie, maar verwoord baie tipiese Jeroen Bosch-beelde. Net soos Opperman beskryf Jef van Kempen ’n droomwêreld aan die nagmerrie-agtige kant in sy volgende gedig:

Theater

Stel je voor: een toneel van dolende nachtvogels

boven een doorweekte woestijn, in een duister

hospitaal voor koortsige landlopers.

Stel je voor: een opera van rondborstige gedrochten,

verwekt in een glazen stolp, amechtig lispelend,

op kromme stelten strompelend, in een vuile

sneeuwjacht van de diepe winter.

Eind goed al goed vonden de trage doden hun draai

en bestegen, tegen de keer, het paard van Troje

en maakten hun dromen waar.

In die uitsnede van “De tuin der Lusten” hierbo is duidelik in strofe 1 ’n “dolende nachtvogel-” in die gedaante van ’n vet uil te sien (met alle simboliek verbonde aan uile soos erotiek en dwaasheid in die Middeleeue). Is hierdie mense op die afbeelding nie belustig – koorsig van lus en wellus, hoop en wanhoop nie? Strofe 3 begin met “verwekt in een glazen stolp”. Inderdaad. In die middel is drie mense onder ’n soort deurskynende klokkie met mekaar besig. Selfs die Moredans wat Opperman ook beskryf het, kry ’n plekkie in Van Kempen se gedig met “Eind goed al goed vonden de trage doden hun draai / en bestegen, tegen de keer, het paard van Troje” (Strofe 4-5).

Bernard Odendaal het die gedig van Van Kempen in Afrikaans vertaal. Vertalings is vir digters soos toonlere vir komponiste. Oefenlopies. Woorde soos “landlopers” en “amechtig” moes vir Odendaal nogal moeite gekos het. Deur vertalings soos hierdie word die Afrikaanse poësie verryk.

Teater

Stel jou voor: ’n toneel van dolende nagvoëls

bokant ’n deurweekte woestyn, in ’n donker

hospitaal vir koorsige boemelaars.

Stel jou voor: ’n opera van rondborstige gedrogte

verwek onder ’n glasstolp, uitasem lispelend,

op krom stelte strompelend, morsig aan die

jag in die diepwintersneeuw.

Einde goed alles goed kry die trae dooies hul draai

en bestyg, dwarstrekkerig, die perd van Troje

en maak hulle drome waar.

Laat digters na Afrikaans toe vertaal en verhinder hulle kinderlike verwondering en bemoeienis nié. Speel ek duiwelsadvokaat?

CARINA VAN DER WALT

Carina van der Walt over Jeroen Bosch

Thursday, March 31st, 2016

Eerder gepubliceerd in: Versindaba – ‘n Kollektiewe weblog vir die Afrikaanse digkuns –

http://versindaba.co.za/2016/03/31/carina-van-der-walt-jeroen-bosch-se-skilderye/

Carina van der Walt – Jeroen Bosch – D.J. Opperman – Johan van Wyk – Gert Strydom – Breyten Breytenbach – W.E.G. Louw – TT Cloete – Jef van Kempen – Bernard Odendaal

fleursdumal.nl magazine for art & literature

More in: # Archive S.A. literature, Bernard Odendaal, Breyten Breytenbach, Carina van der Walt, DICTIONARY OF IDEAS, Jef van Kempen, Jheronimus Bosch, Kempen, Jef van, Literaire Salon in 't Wevershuisje, T .T. Cloete, VERTAALVRUCHT, Walt, Carina van der

Rainer Maria Rilke

(1875 – 1926)

Leda

Als ihn der Gott in seiner Not betrat,

erschrak er fast, den Schwan so schön zufinden;

er ließ sich ganz verwirrt in ihm verschwinden.

Schon aber trug ihn sein Betrug zur Tat,

bevor er noch des unerprobten Seins

Gefühle prüfte. Und die Aufgetane

erkannte schon den Kommenden im Schwane

und wußte schon: er bat um Eins,

das sie, verwirrt in ihrem Widerstand,

nicht mehr verbergen konnte. Er kam nieder

und halsend durch die immer schwächere Hand

ließ sich der Gott in die Geliebte los.

Dann erst empfand er glücklich sein Gefieder

und wurde wirklich Schwan in ihrem Schoß.

Rainer Maria Rilke Gedichte

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive Q-R, Rilke, Rainer Maria

Guillaume Apollinaire

(1880 – 1918)

Il y a

Il y a un vaisseau qui a emporté ma bien-aimée

Il y a dans le ciel six saucisses et la nuit venant on dirait des asticots dont naîtraient les étoiles

Il y a un sous-marin ennemi qui en voulait à mon amour

Il y a mille petits sapins brisés par les éclats d’obus autour de moi

Il y a un fantassin qui passe aveuglé par les gaz asphyxiants

Il y a que nous avons tout haché dans les boyaux de Nietzsche de Goethe et de Cologne

Il y a que je languis après une lettre qui tarde

Il y a dans mon porte-cartes plusieurs photos de mon amour

Il y a les prisonniers qui passent la mine inquiète

Il y a une batterie dont les servants s’agitent autour des pièces

Il y a le vaguemestre qui arrive au trot par le chemin de l’Abre isolé

Il y a dit-on un espion qui rôde par ici invisible comme l’horizon dont il s’est indignement revêtu et avec quoi il se confond

Il y a dressé comme un lys le buste de mon amour

Il y a un capitaine qui attend avec anxiété les communications de la T.S.F. sur l’Atlantique

Il y a à minuit des soldats qui scient des planches pour les cercueils

Il y a des femmes qui demandent du maïs à grands cris devant un Christ sanglant à Mexico

Il y a le Gulf Stream qui est si tiède et si bienfaisant

Il y a un cimetière plein de croix à 5 kilomètres

Il y a des croix partout de-ci de-là

Il y a des figues de barbarie sur ces cactus en Algérie

Il y a les longues mains souples de mon amour

Il y a un encrier que j’avais fait dans une fusée de 15 centimètres et qu’on n’a pas laissé partir

Il y a ma selle exposée à la pluie

Il y a les fleuves qui ne remontent pas leur cours

Il y a l’amour qui m’entraîne avec douceur

Il y avait un prisonnier boche qui portait sa mitrailleuse sur son dos

Il y a des hommes dans le monde qui n’ont jamais été à la guerre

Il y a des Hindous qui regardent avec étonnement les campagnes occidentales

Ils pensent avec mélancolie à ceux dont ils se demandent s’ils les reverront

Car on a poussé très loin durant cette guerre l’art de l’invisibilité

Guillaume Apollinaire poésie

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: #Archive Concrete & Visual Poetry, *War Poetry Archive, Apollinaire, Guillaume, Archive A-B

William Shakespeare

(1564-1616)

In this dagger

Is this a dagger which I see before me,

The handle toward my hand?

Come, let me clutch thee.

I have thee not, and yet I see thee still.

Art thou not, fatal vision, sensible

To feeling as to sight? or art thou but

A dagger of the mind, a false creation,

Proceeding from the heat-oppressed brain?

William Shakespeare, “Macbeth”, Act 2 scene 1

Shakespeare 400 (1616 – 2016)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Shakespeare, William

60 auteurs, 14 locaties, 1 nacht

Literair festival in het centrum van Rotterdam op zaterdag 8 oktober 2016 met optredens van diverse auteurs uit Nederland en Vlaanderen.

# Meer info op website Woordnacht 2016

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Art & Literature News, Literary Events, MODERN POETRY, MUSIC

Het Feest der Poëzie presenteert op zaterdagavond 8 oktober de derde editie van de Salon der Verzen bij het Pianola Museum te Amsterdam. Daarbuiten gaat de Poëziebar met absint en sonnetten weer op pad, ditmaal naar Wageningen en Leiden, en verschijnt deze ook bij de Amsterdamse Museumnacht.

Het Feest der Poëzie presenteert op zaterdagavond 8 oktober de derde editie van de Salon der Verzen bij het Pianola Museum te Amsterdam. Daarbuiten gaat de Poëziebar met absint en sonnetten weer op pad, ditmaal naar Wageningen en Leiden, en verschijnt deze ook bij de Amsterdamse Museumnacht.

Salon der Verzen: Eerder al tweemaal uitverkocht en nu terug in het nieuwe seizoen! Een geheel nieuw programma met werk van dichters van deze tijd, klassieke liederen, proza, verwondering en oude media. Met ditmaal als gastdichter Lennard van Rij. Verder gastvrouw Marijke Brekelmans, conservator Kasper Janse, verwonderaar Arjan van Vembde, sopraan Susanne Winkler, pianist Daan van de Velde, en voordrachtskunstenaar Simon Mulder.

Reserveren wordt aangeraden!

Praktische informatie Salon der Verzen

Entree: 15 euro/12,50 euro

(korting: student/65+/Stadspas)

8 oktober 2016

Adres: Pianolamuseum,

Westerstraat 106, Amsterdam

Aanvang: 20:30

Zaal open: 20:00

Reserveren: info@pianola.nl of www.feestderpoezie.nl

Informatie: www.feestderpoezie.nl

# Meer info op website feestderpoëzie

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Art & Literature News, CLASSIC POETRY, Feest der Poëzie, Literary Events, MUSIC

Karoline von Günderrode

(1780 – 1806)

Novalis

Novalis, deinen heil’gen Seherblicken

Sind aufgeschlossen aller Welten Räume,

Dir offenbart sich weihend das Gemeine,

Du schaust es in prophetischem Entzücken.

Du siehst der Dinge zukunftsvolle Keime

Und zu des Weltalls ewigen Geschicken,

Die gern dem Aug’ der Menschen sich entrücken,

Wirst du geführt durch ahndungsvolle Träume.

Du siehst das Recht, das Wahre, Schöne siegen,

Die Zeit sich selbst im Ewigen zernichten

Und Eros ruhend sich dem Weltall fügen;

So hat der Weltgeist liebend sich vertrauet

Und offenbart in Novalis Dichten,

Und wie Narziß in sich verliebt geschauet.

Karoline Günderrode Gedichte

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive G-H, Karoline von Günderrode, Novalis

Leigh Hunt

(1784 – 1859)

Bellman’s Verses For 1814

Huzza, my boys! our friends the Dutch have risen,

Our good old friends, and burst the Tyrant’s prison!

Aye, and have done it without bloodshed too,

Like men, to sense as well as freedom true.

The moment, I’ll be sworn, that Ocean heard it,

With a new dance of waters it bestirr’d it;

And Trade, reviving from her trance of death,

Took a new lease of sunshine and of breath.

Let’s aid them, my fine fellows, all we can:—

Where’s finer business for an Englishman—

Who knows what ’tis to eat his own good bread,

And see his table-cloth securely spread—

Than helping to set free a neighbour’s oven?

Huzza! The Dutch for ever! Orange Boven!

Leigh Hunt poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive G-H, Hunt, Leigh

Max Jacob

(1876 – 1944)

Désir

Deux cous comme deux serpents

ne savent où ils se posent

deux baisers ferment la rose

ils ont la saveur du sang

Pays caché par l’habit

ce corps blanc qui me subit,

tu m’es la natale terre

de ma grêle et mon tonnerre

Qu’importe si l’enfer en tremble

si le ciel m’ôte pitié on meurt

de soif d’être ensemble

au même buisson liés

Bûche au foyer devient cendre!

et le désir de chacun?

la ferraille d’un scaphandre

sur un visage défunt

Aphrodite est la merveille

toujours nouvelle,

emplumée toujours espoir

se réveille qui toujours part en fumée

Quel refrain, la flatterie!

vain refrain deviendra gris

refrain de l’Avril mépris

Agenouille-toi et prie.

Max Jacob poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive I-J, Jacob, Max

William Shakespeare

(1564-1616)

Come, gentle night

“Come, gentle night; come, loving, black-browed night;

Give me my Romeo; and, when I shall die,

Take him and cut him out in little stars,

And he will make the face of heaven so fine

That all the world will be in love with night …”

William Shakespeare, Romeo and Juliet

Shakespeare 400 (1616 – 2016)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Shakespeare, William

Adele Schopenhauer

(1797 – 1849)

Stolz und stumm

“Ich weiß es wohl, Du hast um mich geweint”

Es soll kein Wort, kein Hauch die Überzeugung nennen,

Es soll Dein Wesen nur still leuchtend in mir brennen;

Wenn Alles an mir kalt und regungslos erscheint,

Was kümmert es die Welt? Du hast um mich geweint!

Du weißt es wohl, wir haben stumm geweint!

Wir tragen durch die Welt die schwere Last im Innern,

Es braucht kein flüchtig Wort zu ewigem Erinnern,

Da uns kein glückliches zu ew’gem Bund vereint –

Was böte mir die Welt? Du hast um mich geweint!

Adele Schopenhauer Gedichte

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, CLASSIC POETRY

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature