Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

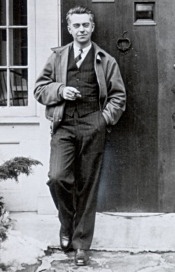

Hart Crane

(1889 – 1932)

At Melville’s Tomb

Often beneath the wave, wide from this ledge

The dice of drowned men’s bones he saw bequeath

An embassy. Their numbers as he watched,

Beat on the dusty shore and were obscured.

And wrecks passed without sound of bells,

The calyx of death’s bounty giving back

A scattered chapter, livid hieroglyph,

The portent wound in corridors of shells.

Then in the circuit calm of one vast coil,

Its lashings charmed and malice reconciled,

Frosted eyes there were that lifted altars;

And silent answers crept across the stars.

Compass, quadrant and sextant contrive

No farther tides . . . High in the azure steeps

Monody shall not wake the mariner.

This fabulous shadow only the sea keeps.

Hart Crane poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive C-D, Crane, Hart, Herman Melville

Leigh Hunt

(1784 – 1859)

Ariadne Waking

The moist and quiet morn was scarcely breaking,

When Ariadne in her bower was waking;

Her eyelids still were closing, and she heard

But indistinctly yet a little bird,

That in the leaves o’erhead, waiting the sun,

Seemed answering another distant one.

She waked, but stirred not, only just to please

Her pillow-nestling cheek; while the full seas,

The birds, the leaves, the lulling love o’ernight

The happy thought of the returning light,

The sweet, self-willed content, conspired to keep

Her senses lingering in the feel of sleep;

And with a little smile she seemed to say,

“I know my love is near me, and ’tis day.”

Leigh Hunt poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive G-H, Hunt, Leigh

Rainer Maria Rilke

(1875 – 1926)

Der Gefangene

I

Meine Hand hat nur noch eine

Gebärde, mit der sie verscheucht;

auf die alten Steine

fällt es aus Felsen feucht.

Ich höre nur dieses Klopfen

und mein Herz hält Schritt

mit dem Gehen der Tropfen

und vergeht damit.

Tropften sie doch schneller,

käme doch wieder ein Tier.

Irgendwo war es heller -.

Aber was wissen wir.

II

Denk dir, das was jetzt Himmel ist und Wind,

Luft deinem Mund und deinem Auge Helle,

das würde Stein bis um die kleine Stelle

an der dein Herz und deine Hände sind.

Und was jetzt in dir morgen heißt und: dann

und: späterhin und nächstes Jahr und weiter –

das würde wund in dir und voller Eiter

und schwäre nur und bräche nicht mehr an.

Und das was war, das wäre irre und

raste in dir herum, den lieben Mund

der niemals lachte, schäumend von Gelächter.

Und das was Gott war, wäre nur dein Wächter

und stopfte boshaft in das letzte Loch

ein schmutziges Auge. Und du lebtest doch.

Rainer Maria Rilke Gedichte

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive Q-R, Rilke, Rainer Maria

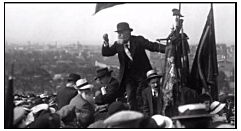

Jean Jaurès

(1859 – 1914)

Dans le bleu

L’effort de la lumière pour percer l’obstacle s’exprime par le

rayon jaune et lui donne un sens ; l’effort de l’ombre pour venir

à nous à travers la lumière, en l’adoucissant et en s’y égayant,

s’exprime par le rayon bleu.

Il serait singulier, en effet, que la lumière bleue se manifes-

tât toujours quand un fond obscur est vu à travers la clarté, et

que ce fait-là n’eût point de signification. Quand un vase d’eau

claire est posé sur un fond noir, l’eau paraît bleuâtre. Dans les

rayonnantes journées d’été, l’ombre portée sur un mur blanc,

vu à distance, semble bleue : les montagnes noires, à mesure

qu’on s’en éloigne par un beau temps, bleuissent ; et lorsque,

au couchant, un nuage sombre, voisin du soleil, au lieu de s’in-

terposer entre lui et nous, reçoit à sa surface les rayons glis-

sants, il apparaît d’un bleu admirable et il se confond avec le

bleu même du ciel ; si bien que, quand le soleil se cache et que

le prestige s’évanouit, l’œil est étonné de trouver un pesant

nuage là où il n’avait cru rencontrer que la pureté profonde de

l’air. Le ciel qui, la nuit, quand il n’est éclairé que par les

étoiles, est noir, vu à travers la lumière du soleil, apparaît bleu.

Ainsi toutes les grandes manifestations de la couleur bleue

sont liées aux mêmes conditions ; est-ce là un fait fortuit ? Le

bleu, comme pour bien marquer son rapport à l’obscur, confine

au noir et au gris par une multitude de degrés. Le soir, une

partie du ciel est déjà noire qu’une autre partie est encore

bleue ; et il semble au regard qui en fait le tour qu’il passe

seulement d’un bleu plus clair à un bleu plus sombre. À mesure

qu’on s’élève en ballon vers les hauteurs du ciel, le bleu est

plus sombre et plus voisin du noir.

Jean Jaurès poésie

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive I-J, Jaurès, Jean

William Shakespeare

(1564-1616)

The quality of mercy

The quality of mercy is not strain’d,

It droppeth as the gentle rain from heaven

Upon the place beneath. It is twice blest:

It blesseth him that gives and him that takes.

‘T is mightiest in the mightiest: it becomes

The throned monarch better than his crown;

His sceptre shows the force of temporal power,

The attribute to awe and majesty,

Wherein doth sit the dread and fear of kings;

But mercy is above this sceptred sway,

It is enthroned in the hearts of kings,

It is an attribute to God himself;

And earthly power doth then show likest God’s,

When mercy seasons justice. Therefore, Jew,

Though justice be thy plea, consider this,

That in the course of justice none of us

Should see salvation: we do pray for mercy;

And that same prayer doth teach us all to render

The deeds of mercy.

William Shakespeare, “The Merchant of Venice”, Act 4 scene 1

Shakespeare 400 (1616 – 2016)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Shakespeare, William

Guillaume Apollinaire

(1880 – 1918)

Mon Lou la nuit descend

Mon Lou la nuit descend tu es à moi je t’aime

Les cyprès ont noirci le ciel a fait de même

Les trompettes chantaient ta beauté mon bonheur

De t’aimer pour toujours ton cœur près de mon cœur

Je suis revenu doucement à la caserne

Les écuries sentaient bon la luzerne

Les croupes des chevaux évoquaient ta force et ta grâce

D’alezane dorée ô ma belle jument de race

La tour Magne tournait sur sa colline laurée

Et dansait lentement lentement s’obombrait

Tandis que des amants descendaient de la colline

La tour dansait lentement comme une sarrasine

Le vent souffle pourtant il ne fait pas du tout froid

Je te verrai dans deux jours et suis heureux comme un roi

Et j’aime de t’y aimer cette Nîmes la Romaine

Où les soldats français remplacent l’armée prétorienne

Beaucoup de vieux soldats qu’on n’a pu habiller

Ils vont comme des bœufs tanguent comme des mariniers

Je pense à tes cheveux qui sont mon or et ma gloire

Ils sont toute ma lumière dans la nuit noire

Et tes yeux sont les fenêtres d’où je veux regarder

La vie et ses bonheurs la mort qui vient aider

Les soldats las les femmes tristes et les enfants malades

Des soldats mangent près d’ici de l’ail dans la salade

L’un a une chemise quadrillée de bleu comme une carte

Je t’adore mon Lou et sans te voir je te regarde

Ça sent l’ail et le vin et aussi l’iodoforme

Je t’adore mon Lou embrasse-moi avant que je ne dorme

Le ciel est plein d’étoiles qui sont les soldats

Morts ils bivouaquent là-haut comme ils bivouaquaient là-bas

Et j’irai conducteur un jour lointain t’y conduire

Lou que de jours de bonheur avant que ce jour ne vienne luire

Aime-moi mon Lou je t’adore Bonsoir

Je t’adore je t’aime adieu mon Lou ma gloire

Guillaume Apollinaire Poèmes à Lou

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: #Archive Concrete & Visual Poetry, *War Poetry Archive, Apollinaire, Guillaume, Archive A-B

Over ooit

Wij bezitten een stukje van de wereld,

in een stad die wij graag zien. Al met al

gaat het er niet zo krampachtig aan toe

als dorpelingen vrezen. Er stroomt mooi

een rivier langs, niet echt door. Elke avond

lijkt er jong, ieder uur nieuw. Soms denk ik

er minutenlang aan niets, voel ik de rugzak

vol verleden amper. Alles gaat over ooit.

Bert Bevers

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Bevers, Bert

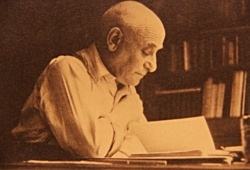

Rainer Maria Rilke

(1875 – 1926)

Die Kurtisane

Venedigs Sonne wird in meinem Haar

ein Gold bereiten: aller Alchemie

erlauchten Ausgang. Meine Brauen, die

den Brücken gleichen, siehst du sie

hinführen ob der lautlosen Gefahr

der Augen, die ein heimlicher Verkehr

an die Kanäle schließt, so daß das Meer

in ihnen steigt und fällt und wechselt. Wer

mich einmal sah, beneidet meinen Hund,

weil sich auf ihm oft in zerstreuter Pause

die Hand, die nie an keiner Glut verkohlt,

die unverwundbare, geschmückt, erholt -.

Und Knaben, Hoffnungen aus altem Hause,

gehen wie an Gift an meinem Mund zugrund.

Rainer Maria Rilke Gedichte

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive Q-R, Rilke, Rainer Maria

Leigh Hunt

(1784 – 1859)

Jenny kiss’d Me

Jenny kiss’d me when we met,

Jumping from the chair she sat in;

Time, you thief, who love to get

Sweets into your list, put that in!

Say I’m weary, say I’m sad,

Say that health and wealth have miss’d me,

Say I’m growing old, but add,

Jenny kiss’d me.

Leigh Hunt poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive G-H, Hunt, Leigh

Max Jacob

(1876 – 1944)

Romance

Je garde dans la solitude comme un pressentiment de toi.

Tu viens ! et le ciel se déploie, la forêt, l’océan reculent.

Tous deux le soleil nous désigne par-dessus la ville et les toits les fenêtres renvoient ses lignes les fleurs éclatent comme des voix.

Lorsque ton jardin nous reçoit, ta maison prend un air étrange: comme un reflet, la véranda nous accueille, sourit et change.

Les arbres ont de grands coups d’ailes derrière et devant les buissons.

La vague, au loin, parallèle, se met à briller par frissons.

Je garde dans la solitude comme un pressentiment de toi.

Tu viens ! et le ciel se déploie, la forêt, l’océan reculent.

Max Jacob poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive I-J, Jacob, Max

William Shakespeare

(1564-1616)

To-morrow

To-morrow, and to-morrow, and to-morrow,

Creeps in this petty pace from day to day

To the last syllable of recorded time,

And all our yesterdays have lighted fools

The way to dusty death. Out, out, brief candle!

Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player

That struts and frets his hour upon the stage

And then is heard no more: it is a tale

Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury,

Signifying nothing.

William Shakespeare, “Macbeth”, Act 5 scene 5

Shakespeare 400 (1616 – 2016)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Shakespeare, William

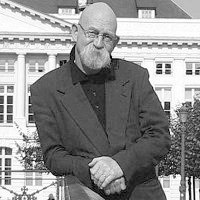

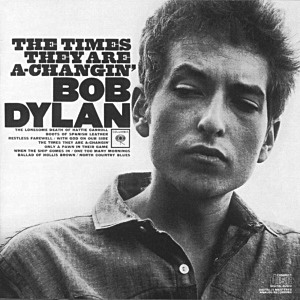

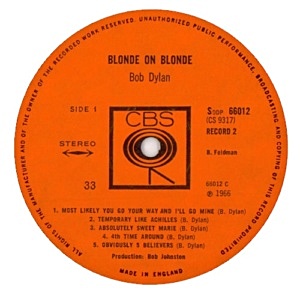

The Nobel Prize in Literature 2016

Bob Dylan

The Nobel Prize in Literature for 2016 is awarded to Bob Dylan: “for having created new poetic expressions within the great American song tradition”.

Bob Dylan Albums

Bob Dylan (1962)

The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan (1963)

The Times They Are A-Changin’ (1964)

Another Side Of Bob Dylan (1964)

Bringing It All Back Home (1965)

Highway 61 Revisited (1965)

Blonde On Blonde (1966)

Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits (1967)

John Wesley Harding (1968)

Nashville Skyline (1969)

Self Portrait (1970)

New Morning (1970)

Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits Vol. 2 (1971)

Pat Garrett & Billy The Kid (1973)

Dylan (1973)

Planet Waves (1974)

Before The Flood (1974)

Blood On The Tracks (1975)

The Basement Tapes (1975)

Desire (1976)

Hard Rain (1976)

Street Legal (1978)

Bob Dylan At Budokan (1978)

Slow Train Coming (1979)

Saved (1980)

Shot Of Love (1981)

Infidels (1983)

Real Live (1984)

Empire Burlesque (1985)

Biograph (1985)

Knocked Out Loaded (1986)

Down In The Groove (1988)

Dylan & The Dead (1989)

Oh Mercy (1989)

Under The Red Sky (1990)

The Bootleg Series Vols. 1-3: Rare And Unreleased 1961-1991 (1991)

Good As I Been to You (1992)

World Gone Wrong (1993)

Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits Vol. 3 (1994)

MTV Unplugged (1995)

The Best Of Bob Dylan (1997)

The Songs Of Jimmie Rodgers: A Tribute (1997)

Time Out Of Mind (1997)

The Bootleg Series, Vol. 4: Bob Dylan Live 1966: The ’Royal Albert Hall’ Concert (1998)

The Essential Bob Dylan (2000)

”Love And Theft” (2001)

The Bootleg Series, Vol. 5: Live 1975: The Rolling Thunder Revue (2002)

Masked And Anonymous: The Soundtrack (2003)

Gotta Serve Somebody: The Gospel Songs Of Bob Dylan (2003)

The Bootleg Series, Vol. 6: Live 1964: Concert At Philharmonic Hall (2004)

The Bootleg Series, Vol. 7: No Direction Home: The Soundtrack (2005)

Live At The Gaslight 1962 (2005)

Live At Carnegie Hall 1963 (2005)

Modern Times (2006)

The Traveling Wilburys Collection (2007)

The Bootleg Series, Vol. 8: Tell Tale Signs: Rare And Unreleased, 1989-2006 (2008)

Together Through Life (2009)

Christmas In The Heart (2009)

The Original Mono Recordings (2010)

The Bootleg Series, Vol. 9: The Witmark Demos: 1962-1964 (2010)

Good Rockin’ Tonight: The Legacy Of Sun (2011)

Timeless (2011)

Tempest (2012)

The Lost Notebooks Of Hank Williams (2011)

The Bootleg Series, Vol. 10: Another Self Portrait (2013)

The Bootleg Series, Vol. 11: The Basement Tapes Complete (2014)

The Bootleg Series, Vol. 12: The Cutting Edge 1965-1966 (2015)

Shadows In The Night (2015)

Fallen Angels (2016)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

13 oct. 2016

More in: Archive C-D, Art & Literature News, Awards & Prizes, Bob Dylan, Dylan, Bob, Literary Events

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature