Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

Fjodor Tjoettsjev

(1803 – 1873)

Een skaldenharp

O skaldenharp, zo ruw terzij gelegd,

in stof, in duisternis kwam jij terecht!

Maar straalde daar de toverende maan

met blauw-azuren schemerlicht jou aan,

dan werd jouw levendige klank gehoord,

een ziel was jij wier stilte werd verstoord.

Wat werd er in zo’n wonderlijke nacht

niet aan verleden aan het licht gebracht!

Klonk niet uit lang vervlogen tijden daar

de zang van een voorbije meisjesschaar,

in tuinen vrolijk bloeiend keer op keer

het trippelen van tienervoetjes teer?

Fjodor Tjoettsjev, Арфа скальда, 1838

Vertaling Paul Bezembinder, 2016

Een skald is een oud-Noorse hofdichter

Paul Bezembinder: zijn gedichten en vertalingen verschenen in verschillende (online) literaire tijdschriften. Zie meer op zijn website: www.paulbezembinder.nl

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Tjoettsjev, Tjoettsjev, Fodor

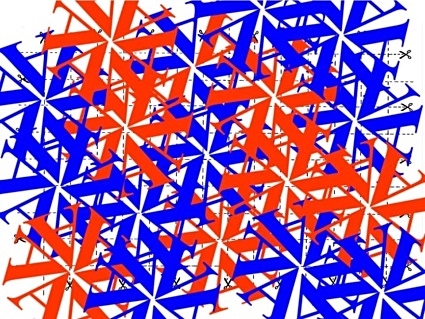

Sérgio Monteiro de Almeida

Poema visual: Presentation 10 (from the kaleidoscope series)

Sérgio Monteiro de Almeida cv:

Curitiba, Brazil (1964). Intermedia visual poet and conceptual artist. – He has published in numerous anthologies and specialized magazines in Brazil and outside; participated in exhibitions of visual poetry as International Biennial of Visual and Alternative Poetry in Mexico (editions from 1987 to 2010); Post-Art International Exhibition of Visual / Experimental Poetry, San Diego State University-USA (1988); 51 and 53 Venice Biennial (2005 and 2009). – He published in 2007 the book Sérgio Monteiro de Almeida with a global vision about his work as a visual artist and poet. – This book was incorporated into the “Artist Books” collection of the New York City Library (USA). – Author of the CD of kinetic visual poems (EU) NI/IN VERSO (still unpublished). – He presented urban interventions in Curitiba, San Diego, Seattle, New York, Paris, Rome. – In 2014 and 2015 visual poems published in the Rampike experimental literature magazine of the University of Windsor, Canada. – He recently had his poems published in Jornal Candido (n. 64) and Relevo (2015 and 2016).

More about his work:

Livro eletrônico http://issuu.com/boek861/docs/sergio_monteiro_libro;

Enciclopédia Itaú Cultural de artes visuais www.itaucultural.com.br;

Videos no Youtube: http://www.youtube.com/user/SergioMAlmeida

Sérgio Monteiro de Almeida

Curitiba – PR – Brazil

email: sergio.ma@ufpr.br

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: *Concrete + Visual Poetry K-O, Archive M-N, Sérgio Monteiro de Almeida

Concreted, Unli/oving

They lack in their memories, their being:

Thesmellofasummereveningwalking

downtotheriverwherefishareleaping

&theairisfullofmayfliesandfluff

fromtallreedsalongtheditches

withthesundazzlingingoldenslant;

Thefeeloficywindblastingacross

floodedlevelsbeforedawnwhenstars

aredimmingandtheeastbeginstobrighten

crunchingthroughfrozenpuddlesfeet

sinkingintothesoftnessofthemudbelow;

Thecoloursofbrowningleavesonbranches

alongtheridgeinhighchalkcountry

thevalleyspreadingoutinfront

withitslinesofhedgeautumncopses

&hereandtherehomesteadsincrystallight;

And because of this lack their every action

Brings a world concreted, unli/oving, one

Ending and not to be grasped in loss.

John Leonard

John Leonard lives in Canberra, Australia.

More poetry on website: www.jleonard.net

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive K-L, Leonard, John

Ton van Reen

Het Oor van de Maaier

Sjuu sjuu, het is de zeis

sjuu sjuu, het is de zeis door het koren

sjuu sjuu, het is de zeis

sjuu sjuu, het is de zeis door het koren

sjuu sjuu, het is de zeis

sjuu sjuu, het is de zeis door het koren

sjuu, het is de zeis

sjuu, het is de zeis door het koren

sjuu, het is de zeis

sjuu sjuu, het is de zeis

sjuu sjuu, het is de zeis door het koren

sjuu sjuu, het is de zeis

Ton van Reen: Het Oor van de Maaier

Uit: De naam van het mes. Afrikaanse gedichten

In 2007 verschenen onder de titel: De straat is van de mannen bij BnM Uitgevers in De Contrabas reeks. ISBN 9789077907993 – 56 pagina’s – paperback

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive Q-R, Reen, Ton van, Reen, Ton van, Ton van Reen

Rainer Maria Rilke

(1875 – 1926)

Schlußstück

Der Tod ist groß.

Wir sind die Seinen

lachenden Munds.

Wenn wir uns mitten

im Leben meinen,

wagt er zu weinen

mitten in uns.

Rainer Maria Rilke Gedichte

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive Q-R, Rilke, Rainer Maria

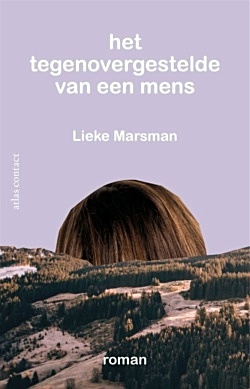

Romandebuut van Lieke Marsman:

Het tegenovergestelde van een mens

Waar het op neerkomt is dat de mensheid als geheel ook eenzaam is. We kunnen er niet tegen dat er niemand iets terugzegt, dat we nog altijd geen dieren hebben horen praten – ja, misschien zo nu en dan in de vorm van het schrille gegil dat onze slachthuizen vult, maar niet met woorden, niet met een oplossing voor de dingen waar we al tijden mee zitten. Zelfs de hemel is leeg. En dus zetten we ons af door al die zwijgende natuur om ons heen te vernietigen, als een wanhopige geliefde die maar niet wordt terug ge-sms’t en het in het café op een zuipen zet.

Nog nooit verscheen er een roman als Het tegenovergestelde van een mens. Lieke Marsman kantelt onze ideeën over klimaatverandering en identiteit op een manier die duizelig maakt.

Lieke Marsman (’s-Hertogenbosch, 1990) is filosoof en een van de populairste en meest gelauwerde dichters van haar generatie. Ze is een graag geziene gast op podia als Lowlands en De Nacht van de Poëzie en haar gedichten en essays verschenen onder meer in De Gids, Tirade en Vrij Nederland. Voor haar meermaals herdrukte debuutbundel Wat ik mijzelf graag voorhoud ontving Marsman in 2011 onder meer de C. Buddingh’-prijs en de Lucy B. en C.W. van der Hoogtprijs. In 2014 verscheen haar tweede bundel De eerste letter. Met Het tegenovergestelde van een mens maakt Marsman haar debuut als prozaschrijver.

Lieke Marsman

Het tegenovergestelde van een mens

Roman, pag. 176

Gepubliceerd 22-06-2017

Uitgeverij Atlas-Contact

Paperback, 19,99

ISBN 9789025446345

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, Archive M-N, Art & Literature News, Marsman, Lieke

John Donne

The Flea

Mark but this flea, and mark in this,

How little that which thou deny’st me is;

It sucked me first, and now sucks thee,

And in this flea our two bloods mingled be;

Thou know’st that this cannot be said

A sin, nor shame, nor loss of maidenhead;

Yet this enjoys before it woo,

And pampered swells with one blood made of two,

And this, alas, is more than we would do.

Oh stay, three lives in one flea spare,

Where we almost, yea, more than married are.

This flea is you and I, and this

Our marriage bed, and marriage temple is;

Though parents grudge, and you, w’are met,

And cloistered in these living walls of jet.

Though use make you apt to kill me,

Let not to that, self-murder added be,

And sacrilege, three sins in killing three.

Cruel and sudden, hast thou since

Purpled thy nail in blood of innocence?

Wherein could this flea guilty be,

Except in that drop which it sucked from thee?

Yet thou triumph’st and say’st that thou

Find’st not thyself, nor me the weaker now;

‘Tis true, then learn how false fears be:

Just so much honor, when thou yield’st to me,

Will waste, as this flea’s death took life from thee

John Donne (1572 – 1631)

Poem: The Flea

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive C-D, Donne, John

Aleksandr Blok

(1880–1921)

Wat is het zwaar

Ginds is een mens verbrand. (Fet)

Wat is het zwaar om hier op aard te zijn,

te doen alsof je niet al omgekomen bent,

steeds dit tragisch spel van angst en pijn

te zien voor wie het leven nog niet kent,

en steeds in boze dromen, nacht na nacht,

te vragen naar wat vragen niet verdraagt,

opdat hun in der schone kunsten pracht

de weerschijn van een vurig leven daagt!

Aleksandr Blok, Как тяжело ходить среди людей, 1910

Vertaling Paul Bezembinder 2016

Paul Bezembinder: zijn gedichten en vertalingen verschenen in verschillende (online) literaire tijdschriften. Zie meer op zijn website: www.paulbezembinder.nl

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Blok, Blok, Aleksandr

Sibylla Schwarz

Die Lieb ist blind, und gleichwohl kan sie sehen

Die Lieb ist blind, und gleichwohl kan sie sehen,

hat ein Gesicht, und ist doch stahrenblind,

sie nennt sich groß, und ist ein kleines Kind,

ist wohl zu Fuß, und kan dannoch nicht gehen.

Doch diss muß man auff ander’ art verstehen:

sie kan nicht sehn, weil ihr Verstand zerrint,

und weil das Aug des Herzens ihr verschwindt,

so siht sie selbst nicht, was ihr ist geschehen.

Das, was sie liebt, hat keinen Mangel nicht,

wie wohl ihm mehr, als andern, offt gebricht.

Das, was sie liebt, kan ohn Gebrechen leben;

doch weil man hier ohn Fehler nichtes find,

so schließ ich fort: Die Lieb ist sehend blind:

sie siht selbst nicht, und kans Gesichte geben.

Sibylla Schwarz (1621 – 1638)

Gedicht: Die Lieb ist blind, und gleichwohl kan sie sehen

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, SIbylla Schwarz

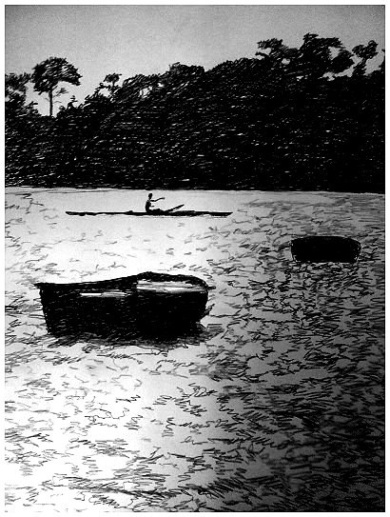

Vincent Berquez©: Drawing Nr. 11

Vincent Berquez is a London–based artist and poet. He has published in Britain, Europe, America and New Zealand. His work is in many anthologies, collections and magazine worldwide. Vincent Berquez was requested to write a Tribute as part of ‘Poems to the American People’ for the Hastings International Poetry Festival for 9/11, read by the mayor of New York at the podium. He has also been commissioned to write a eulogy by the son of Chief Albert Nwanzi Okoluko, the Ogimma Obi of Ogwashi-Uku to commemorate the death of his father. Berquez has been a judge many times, including for Manifold Magazine and had work read as part of Manifold Voices at Waltham Abbey. He has recited many times, including at The Troubadour and the Pitshanger Poets, in London. In 2006 his name was put forward with the Forward Prize for Literature. He recently was awarded a prize with Decanto Magazine. Berquez is now a member of London Voices who meet monthly in London, United Kingdom.

Vincent Berquez has also been collaborating in 07/08 with a Scottish composer and US film maker to produce a song-cycle of seven of his poems for mezzo-soprano and solo piano. These are being recorded at the Royal College of Music under the directorship of the concert pianist, Julian Jacobson. In 2009 he will be contributing 5 poems for the latest edition of A Generation Defining Itself, as well as 3 poems for Eleftheria Lialios’s forthcoming book on wax dolls published in Chicago. He also made poetry films that have been shown at various venues, including a Polish/British festival in London, Jan 07.

As an artist Vincent Berquez has exhibited world wide, winning prizes, such as at the Novum Comum 88’ Competition in Como, Italy. He has worked with an art’s group, called Eins von Hundert, from Cologne, Germany for over 16 years. He has shown his work at the Institute of Art in Chicago, US, as well as many galleries and institutions worldwide. Berquez recently showed his paintings at the Lambs Conduit Festival, took part in a group show called Gazing on Salvation, reciting his poetry for Lent and exhibiting paintings/collages. In October he had a one-man show at Sacred Spaces Gallery with his Christian collages in 2007. In 2008 Vincent Berquez had a solo show of paintings at The Foundlings Museum and in 2011 an exposition with new work in Langham Gallery London.

fleursdumal.nl magazine for art & literature

More in: Berquez, Vincent, FDM Art Gallery, Vincent Berquez

Deaths of Little Children

Deaths of Little Children

by Leigh Hunt

A Grecian philosopher being asked why he wept for the death of his son, since the sorrow was in vain, replied, “I weep on that account.” And his answer became his wisdom. It is only for sophists to contend that we, whose eyes contain the fountains of tears, need never give way to them. It would be unwise not to do so on some occasions. Sorrow unlocks them in her balmy moods. The first bursts may be bitter and overwhelming; but the soil on which they pour would be worse without them. They refresh the fever of the soul—the dry misery which parches the countenance into furrows, and renders us liable to our most terrible “flesh-quakes.”

There are sorrows, it is true, so great, that to give them some of the ordinary vents is to run a hazard of being overthrown. These we must rather strengthen ourselves to resist, or bow quietly and drily down, in order to let them pass over us, as the traveller does the wind of the desert. But where we feel that tears would relieve us, it is false philosophy to deny ourselves at least that first refreshment; and it is always false consolation to tell people that because they cannot help a thing, they are not to mind it. The true way is, to let them grapple with the unavoidable sorrow, and try to win it into gentleness by a reasonable yielding. There are griefs so gentle in their very nature that it would be worse than false heroism to refuse them a tear. Of this kind are the deaths of infants. Particular circumstances may render it more or less advisable to indulge in grief for the loss of a little child; but, in general, parents should be no more advised to repress their first tears on such an occasion, than to repress their smiles towards a child surviving, or to indulge in any other sympathy. It is an appeal to the same gentle tenderness; and such appeals are never made in vain. The end of them is an acquittal from the harsher bonds of affliction—from the typing down of the spirit to one melancholy idea.

It is the nature of tears of this kind, however strongly they may gush forth, to run into quiet waters at last. We cannot easily, for the whole course of our lives, think with pain of any good and kind person whom we have lost. It is the divine nature of their qualities to conquer pain and death itself; to turn the memory of them into pleasure; to survive with a placid aspect in our imaginations. We are writing at this moment just opposite a spot which contains the grave of one inexpressibly dear to us. We see from our window the trees about it, and the church spire. The green fields lie around. The clouds are travelling overhead, alternately taking away the sunshine and restoring it. The vernal winds, piping of the flowery summer-time, are nevertheless calling to mind the far-distant and dangerous ocean, which the heart that lies in that grave had many reasons to think of. And yet the sight of this spot does not give us pain. So far from it, it is the existence of that grave which doubles every charm of the spot; which links the pleasures of our childhood and manhood together; which puts a hushing tenderness in the winds, and a patient joy upon the landscape; which seems to unite heaven and earth, mortality and immortality, the grass of the tomb and the grass of the green field; and gives a more maternal aspect to the whole kindness of nature. It does not hinder gaiety itself. Happiness was what its tenant, through all her troubles, would have diffused. To diffuse happiness, and to enjoy it, is not only carrying on her wishes, but realising her hopes; and gaiety, freed from its only pollutions, malignity and want of sympathy, is but a child playing about the knees of its mother.

The remembered innocence and endearments of a child stand us instead of virtues that have died older. Children have not exercised the voluntary offices of friendship; they have not chosen to be kind and good to us; nor stood by us, from conscious will, in the hour of adversity. But they have shared their pleasures and pains with us as well as they could; the interchange of good offices between us has, of necessity, been less mingled with the troubles of the world; the sorrow arising from their death is the only one which we can associate with their memories. These are happy thoughts that cannot die. Our loss may always render them pensive; but they will not always be painful. It is a part of the benignity of Nature that pain does not survive like pleasure, at any time, much less where the cause of it is an innocent one. The smile will remain reflected by memory, as the moon reflects the light upon us when the sun has gone into heaven.

When writers like ourselves quarrel with earthly pain (we mean writers of the same intentions, without implying, of course, anything about abilities or otherwise), they are misunderstood if they are supposed to quarrel with pains of every sort. This would be idle and effeminate. They do not pretend, indeed, that humanity might not wish, if it could, to be entirely free from pain; for it endeavours, at all times, to turn pain into pleasure: or at least to set off the one with the other, to make the former a zest and the latter a refreshment. The most unaffected dignity of suffering does this, and, if wise, acknowledges it. The greatest benevolence towards others, the most unselfish relish of their pleasures, even at its own expense, does but look to increasing the general stock of happiness, though content, if it could, to have its identity swallowed up in that splendid contemplation. We are far from meaning that this is to be called selfishness. We are far, indeed, from thinking so, or of so confounding words. But neither is it to be called pain when most unselfish, if disinterestedness by truly understood. The pain that is in it softens into pleasure, as the darker hue of the rainbow melts into the brighter. Yet even if a harsher line is to be drawn between the pain and pleasure of the most unselfish mind (and ill-health, for instance, may draw it), we should not quarrel with it if it contributed to the general mass of comfort, and were of a nature which general kindliness could not avoid. Made as we are, there are certain pains without which it would be difficult to conceive certain great and overbalancing pleasures. We may conceive it possible for beings to be made entirely happy; but in our composition something of pain seems to be a necessary ingredient, in order that the materials may turn to as fine account as possible, though our clay, in the course of ages and experience, may be refined more and more. We may get rid of the worst earth, though not of earth itself.

Now the liability to the loss of children—or rather what renders us sensible of it, the occasional loss itself—seems to be one of these necessary bitters thrown into the cup of humanity. We do not mean that every one must lose one of his children in order to enjoy the rest; or that every individual loss afflicts us in the same proportion. We allude to the deaths of infants in general. These might be as few as we could render them. But if none at all ever took place, we should regard every little child as a man or woman secured; and it will easily be conceived what a world of endearing cares and hopes this security would endanger. The very idea of infancy would lose its continuity with us. Girls and boys would be future men and women, not present children. They would have attained their full growth in our imaginations, and might as well have been men and women at once. On the other hand, those who have lost an infant, are never, as it were, without an infant child. They are the only persons who, in one sense, retain it always, and they furnish their neighbours with the same idea. The other children grow up to manhood and womanhood, and suffer all the changes of mortality. This one alone is rendered an immortal child. Death has arrested it with his kindly harshness, and blessed it into an eternal image of youth and innocence.

Of such as these are the pleasantest shapes that visit our fancy and our hopes. They are the ever-smiling emblems of joy; the prettiest pages that wait upon imagination. Lastly, “Of these are the kingdom of heaven.” Wherever there is a province of that benevolent and all-accessible empire, whether on earth or elsewhere, such are the gentle spirits that must inhabit it. To such simplicity, or the resemblance of it, must they come. Such must be the ready confidence of their hearts and creativeness of their fancy. And so ignorant must they be of the “knowledge of good and evil,” losing their discernment of that self-created trouble, by enjoying the garden before them, and not being ashamed of what is kindly and innocent.

Deaths of Little Children

by Leigh Hunt (1784 – 1859)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive G-H, Archive G-H, Galerie des Morts, Hunt, Leigh

Onias Landveld

wordt op 27 augustus, tijdens ‘Boeken rond het Paleis’, geïnstalleerd als stadsdichter van Tilburg. De huidige stadsdichter Martin Beversluis neemt dan afscheid.

De nieuwe stadsdichter wordt gepresenteerd door Wilbert van Herwijnen, voorzitter van de Stadsdichterscommissie, en Marcelle Hendrickx, wethouder Cultuur in de gemeente Tilburg.

Onias Landveld is dichter en Spoken Word Artist, winnaar van de 2015 Van Dale Spoken Award voor storytelling en jurylid Tilburgs Junior Stadsdichter. Hij geeft cursussen in Public Speaking en Corporate Storytelling en schrijft business concepten en kinderverhalen.

Tilburg heeft sinds 2003 een stadsdichter. Iedere 2 jaar benoemt het college een nieuwe. De Stadsdichterscommissie draagt een dichter voor die zij selecteert uit een lijst van dichters, o.a. aangedragen door de stad. Eerdere stadsdichters waren JACE van de Ven, Nick J. Swarth, Frank van Pamelen, Cees van Raak en Esther Porcelijn. De stadsdichter schrijft gedichten over Tilburg en geeft voordrachten en performances. Hij of zij heeft daarbij de vrijheid om de onderwerpen te bepalen. Het gaat om minimaal 6 gedichten per jaar, verspreid over het jaar.

Onias Landveld nieuwe stadsdichter Tilburg 2017-2019

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive K-L, Art & Literature News, Beversluis, Martin, City Poets / Stadsdichters, Landveld, Onias

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature