Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

Leo van der Sterren

Wij zijn vriezen

wij zijn weg hè wij zijn vriezen

hè de kletsnatte wouden

of meren met hun merensteden in

bijvoorbeeld cumbria of friesland wij

opperden sinds bejaarde jaren

geen flinter vorst meer onze

identiteit bepaald als schots wij

hebben onszelf kenmerken aangemeten

en volksgeaardheid toegedicht

die ons eilandig ons ellendig onderscheidt

van tuten en polakken en teutonen

van lappen balten flarden geen

fjeld die de vriezer velt wij

hebben de chromen zekerheid van

het witte noodlot en de tumorvormige

hardrock in alle humorloze somberheid

omarmd en hebben onze trekken thuis

gekregen wij op deze humus zijn

het vriezen van miniem verliezen

Leo van der Sterren (1959) publiceerde gedichten, verhalen en opstellen in o.a. De Gids, Tzum, Maatstaf, Optima, De Tweede Ronde, De Parelduiker, Gierik/NVT en in een aantal e-zines (Circumplaudo, Kosmose, enz.). Daarnaast publiceerde hij opstellen over Engelstalige literatuur in Hollands Maandblad.

Leo van der Sterren poetry

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Sterren, Leo van der

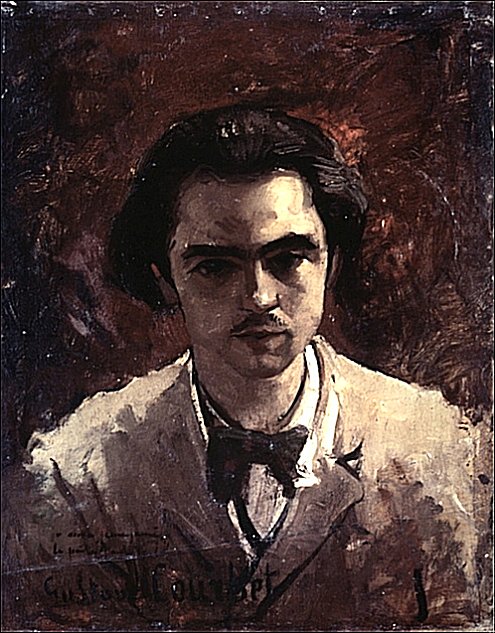

.jpg)

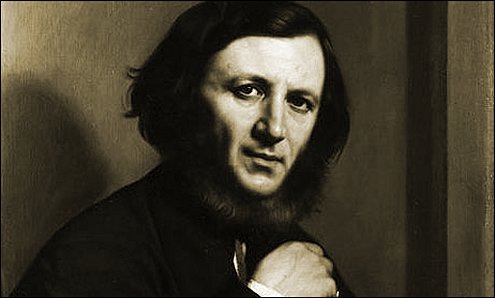

W i l l e m B i l d e r d i j k

(1756-1831)

M i s b r u i k

Ziet men aan de dorenstruiken

’t Geurig roosjen niet ontluiken,

Lentes uitgezochten roem?

Ook distel, ook de netel,

Heeft haar plaats om Floreaas zetel,

Ieder braamsteng draagt haar bloem.

Ach, in alles is genieten;

Slechts het misbruik schept verdrieten.

Waarom grijpt ge woest in ’t rond?

Laat uwe oogen dankbaar weiden

Waar de schoonheên zich verspreiden;

’t Is niet al voor hand of mond.

Ieder zintuig heeft zijn waarde;

Ieder heeft zijn deel op aarde:

Riek het bloemtjen; smaak de vrucht;

Zie Natuur haar kleed schakeeren;

Hoor het boschchoor kwinkeleeren;

Voel den zoelen kus der lucht!

Waan niet, als een God der Goden!

Alles onder uw geboden;

Dienstbaar aan uw grilligheden!

Stervling, stel uw zwelgzucht palen;

Waar Gods weldaân op u dalen,

Wees met wat Hy schenkt te vreên

1823

.jpg)

Willem Bilderdijk gedichten

k e m p i s p o e t r y m a g a z i n e

More in: Archive A-B, Bilderdijk, Willem

.jpg)

W i l l e m K l o o s

(1859-1938)

Wanneer ik dood ben, lief

Wanneer ik dood ben, lief, en iemand zegt,

Dat ik zo niets was, dan zult Gij oprijzen,

Hem op dees allerlaatste bladen wijzen,

En zeggen: "Hij was groot! En die het zegt,

Ben ik, die ‘t weet: want ik, die altijd vecht

Met mensen, om mijns-zelfs wil, die durf eisen

Dat àlles voor mij wijkt, – ik kan ‘t bewijzen:

Heb ik niet zelf hem in zijn graf gelegd?"

Ik geef u geen gelijk, want groter is ‘t

Te stérven voor zijn Ikheid, dan te léven:

‘t Zoet leven lokt méér dan een donkre kist.

Maar Gij komt mij nabij in kracht van pijn

En vreugd, en dus wil ‘k U mijn doodsblad geven:

Mijn grootste glorie zal dees bladzij zijn.

Willem Kloos poetry

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Kloos, Willem

.jpg)

Ein altes Blatt

Franz Kafka (1883-1924

Es ist, als wäre viel vernachlässigt worden in der Verteidigung unseres Vaterlandes. Wir haben uns bisher nicht darum gekümmert und sind unserer Arbeit nachgegangen; die Ereignisse der letzten Zeit machen uns aber Sorgen.

Ich habe eine Schusterwerkstatt auf dem Platz vor dem kaiserlichen Palast. Kaum öffne ich in der Morgendämmerung meinen Laden, sehe ich schon die Eingänge aller hier einlaufenden Gassen von Bewaffneten besetzt. Es sind aber nicht unsere Soldaten, sondern offenbar Nomaden aus dem Norden. Auf eine mir unbegreifliche Weise sind sie bis in die Hauptstadt gedrungen, die doch sehr weit von der Grenze entfernt ist. Jedenfalls sind sie also da; es scheint, daß jeden Morgen mehr werden.

Ihrer Natur entsprechend lagern sie unter freiem Himmel, denn Wohnhäuser verabscheuen sie. Sie beschäftigen sich mit dem Schärfen der Schwerter, dem Zuspitzen der Pfeile, mit Übungen zu Pferde. Aus diesem stillen, immer ängstlich rein gehaltenen Platz haben sie einen wahren Stall gemacht. Wir versuchen zwar manchmal aus unseren Geschäften hervorzulaufen und wenigstens den ärgsten Unrat wegzuschaffen, aber es geschieht immer seltener, denn die Anstrengung ist nutzlos und bringt uns überdies in die Gefahr, unter die wilden Pferde zu kommen oder von den Peitschen verletzt zu werden.

Sprechen kann man mit den Nomaden nicht. Unsere Sprache kennen sie nicht, ja sie haben kaum eine eigene. Unter einander verständigen sie sich ähnlich wie Dohlen. Immer wieder hört man diesen Schrei der Dohlen. Unsere Lebensweise, unsere Einrichtungen sind ihnen ebenso unbegreiflich wie gleichgültig. Infolgedessen zeigen sie sich auch gegen jede Zeichensprache ablehnend. Du magst dir die Kiefer verrenken und die Hände aus den Gelenken winden, sie haben dich doch nicht verstanden und werden dich nie verstehen. Oft machen sie Grimassen; dann dreht sich das Weiß ihrer Augen und Schaum schwillt aus ihrem Munde, doch wollen sie damit weder etwas sagen noch auch erschrecken; sie tun es, weil es so ihre Art ist. Was sie brauchen, nehmen sie. Man kann nicht sagen, daß sie Gewalt anwenden. Vor ihrem Zugriff tritt man beiseite und überläßt ihnen alles.

Auch von meinen Vorräten haben sie manches gute Stück genommen. Ich kann aber darüber nicht klagen, wenn ich zum Beispiel zusehe, wie es dem Fleischer gegenüber geht. Kaum bringt er seine Waren ein, ist ihm schon alles entrissen und wird von den Nomaden verschlungen. Auch ihre Pferde fressen Fleisch; oft liegt ein Reiter neben seinem Pferd und beide nähren sich vom gleichen Fleischstück, jeder an einem Ende. Der Fleischhauer ist ängstlich und wagt es nicht, mit den Fleischlieferungen aufzuhören. Wir verstehen das aber, schießen Geld zusammen und unterstützen ihn. Bekämen die Nomaden kein Fleisch, wer weiß, was ihnen zu tun einfiele; wer weiß allerdings, was ihnen einfallen wird, selbst wenn sie täglich Fleisch bekommen.

Letzthin dachte der Fleischer, er könne sich wenigstens die Mühe des Schlachtens sparen, und brachte am Morgen einen lebendigen Ochsen. Das darf er nicht mehr wiederholen. Ich lag wohl eine Stunde ganz hinten in meiner Werkstatt platt auf dem Boden und alle meine Kleider, Decken und Polster hatte ich über mir aufgehäuft, nur um das Gebrüll des Ochsen nicht zu hören, den von allen Seiten die Nomaden ansprangen, um mit den Zähnen Stücke aus seinem warmen Fleisch zu reißen. Schon lange war es still, ehe ich mich auszugehen getraute; wie Trinker um ein Weinfaß lagen sie müde um die Reste des Ochsen.

Gerade damals glaubte ich den Kaiser selbst in einem Fenster des Palastes gesehen zu haben; niemals sonst kommt er in diese äußeren Gemächer, immer nur lebt er in dem innersten Garten; diesmal aber stand er, so schien es mir wenigstens, an einem der Fenster und blickte mit gesenktem Kopf auf das Treiben vor seinem Schloß.

»Wie wird es werden?« fragen wir uns alle. »Wie lange werden wir diese Last und Qual ertragen? Der kaiserliche Palast hat die Nomaden angelockt, versteht es aber nicht, sie wieder zu vertreiben. Das Tor bleibt verschlossen; die Wache, früher immer festlich ein- und ausmarschierend, hält sich hinter vergitterten Fenstern. Uns Handwerkern und Geschäftsleuten ist die Rettung des Vaterlandes anvertraut; wir sind aber einer solchen Aufgabe nicht gewachsen; haben uns doch auch nie gerühmt, dessen fähig zu sein. Ein Mißverständnis ist es, und wir gehen daran zugrunde.

Franz Kafka : Ein Landarzt. Kleine Erzählungen (1919)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive K-L, Franz Kafka, Kafka, Franz, Kafka, Franz

Jef van Kempen: Twee gedichten

Intensive care

In deze betonnen duisternis weigert

hij te ontwaken. Het is de dood die

loert en dreigt. In een flits verpletterd,

in dat ene ogenblik teveel,

om precies te zijn: gebroken glas

in zacht vlees, verminkte huid,

geblakerd, afgerukt, met harde hand

ontvreemd in een lieflijk mijnenveld.

Rest alleen: het licht dat als een

wit vlies aan de muren hangt, geluid

dat gaten maakt in zijn hoofd, de geur

van rottend bloed, opgeruimde kamers.

Ongeboren was hij op zijn best,

maar ontdaan van alle alledaagsheid,

van alle onberekenbare motieven,

wist hij nog hoe hij ooit

onder haar rok keek

en bladerde tussen haar benen

en dat alleen een vrolijke gek

de hemel zal zien.

Onzichtbaar

Soms sprak zij van

alle planten van de wereld

die ondergronds verbonden zijn

door middel van onzichtbare draden

en die door chemische stoffen in staat

van seksuele opwinding geraken om daarna

weer snel te bezwijken bij de geringste

tegenslag en dat dit alles een geheim

is dat door god en de heiland en

anderen wordt bewaard.

Zo sprak zij dan.

Ik luisterde.

Jef van Kempen (1948) publiceerde poëzie, biografische artikelen, essays en literaire bloemlezingen. Daarnaast is hij actief als beeldend kunstenaar. Jef van Kempen is medeoprichter en redacteur van o.a. de poëziewebsite: KEMP=MAG – kempis poetry magazine ( www.kempis.nl ) en van de website Antony Kok Magazine ( www. antonykok.nl ) In 1966 publiceerde hij zijn eerste dichtbundel: Wiet. In het najaar van 2010 verschijnt een verzamelbundel met gedichten en illustraties: Laatste bedrijf, gedichten 1963-2009 bij uitgeverij Art Brut, Postbus 117, 5120 AC Rijen, ISBN: 978-90-76326-04-7.

.jpg)

k e m p i s p o e t r y m a g a z i n e

More in: Kempen, Jef van

.jpg)

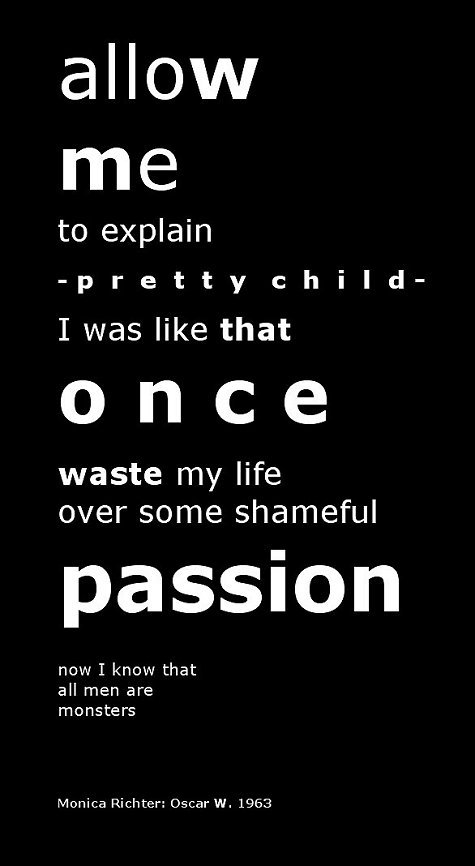

Charles Baudelaire

(1821-1867)

S p l e e n

Pluviôse, irrité contre la vie entière,

De son urne à grands flots vers un froid ténébreux

Aux pâles habitants du voisin cimetière

Et la mortalité sur les faubourgs brumeux.

Mon chat sur le carreau cherchant une litière

Agite sans repos son corps maigre et galeux;

L’âme d’un vieux poète erre dans la gouttière

Avec la triste voix d’un fantôme frileux.

Le bourdon se lamente, et la bûche enfumée

Accompagne en fausset la pendule enrhumée,

Cependant qu’en un jeu plein de sales parfums,

Héritage fatal d’une vieille hydropique,

Le beau valet de coeur et la dame de pique

Causent sinistrement de leurs amours défunts.

J’ai plus de souvenirs que si j’avais mille ans.

Un gros meuble à tiroirs encombré de bilans,

De vers, de billets doux, de procès, de romances,

Avec de lourds cheveux roulés dans des quittances,

Cache moins de secrets que mon triste cerveau.

C’est une pyramide, un immense caveau,

Qui contient plus de morts que la fosse commune.

–Je suis un cimetière abhorré de la lune,

Où comme des remords se traînent de longs vers

Qui s’acharnent toujours sur mes morts les plus chers.

Je suis un vieux boudoir plein de roses fanées,

Où gît tout un fouillis de modes surannées,

Où les pastels plaintifs et les pâles Boucher,

Seuls, respirent l’odeur d’un flacon débouché.

Rien n’égale en longueur les boiteuses journées,

Quand sous les lourds flocons des neigeuses années

L’ennui, fruit de la morne incuriosité,

Prend les proportions de l’immortalité.

–Désormais tu n’es plus, ô matière vivante!

Qu’un granit entouré d’une vague épouvante,

Assoupi dans le fond d’un Saharah brumeux!

Un vieux sphinx ignoré du monde insoucieux,

Oublié sur la carte, et dont l’humeur farouche

Ne chante qu’aux rayons du soleil qui se couche.

Je suis comme le roi d’un pays pluvieux,

Riche, mais impuissant, jeune et pourtant très vieux,

Qui, de ses précepteurs méprisant les courbettes,

S’ennuie avec ses chiens comme avec d’autres bêtes.

Rien ne peut l’égayer, ni gibier, ni faucon,

Ni son peuple mourant en face du balcon,

Du bouffon favori la grotesque ballade

Ne distrait plus le front de ce cruel malade;

Son lit fleurdelisé se transforme en tombeau,

Et les dames d’atour, pour qui tout prince est beau,

Ne savent plus trouver d’impudique toilette

Pour tirer un souris de ce jeune squelette.

Le savant qui lui fait de l’or n’a jamais pu

De son être extirper l’élément corrompu,

Et dans ces bains de sang qui des Romains nous viennent

Et dont sur leurs vieux jours les puissants se souviennent,

Il n’a su réchauffer ce cadavre hébété

Où coule au lieu de sang l’eau verte du Léthé.

Quand le ciel bas et lourd pèse comme un couvercle

Sur l’esprit gémissant en proie aux longs ennuis,

Et que de l’horizon embrassant tout le cercle

Il nous verse un jour noir plus triste que les nuits;

Quand la terre est changée en un cachot humide,

Où l’Espérance, comme une chauve-souris,

S’en va battant les murs de son aile timide

Et se cognant la tête à des plafonds pourris;

Quand la pluie étalant ses immenses traînées

D’une vaste prison imite les barreaux,

Et qu’un peuple muet d’infâmes araignées

Vient tendre ses filets au fond de nos cerveaux,

Des cloches tout à coup sautent avec furie

Et lancent vers le ciel un affreux hurlement,

Ainsi que des esprits errants et sans patrie

Qui se mettent à geindre opiniâtrement.

–Et de longs corbillards, sans tambours ni musique,

Défilent lentement dans mon âme; l’Espoir,

Vaincu, pleure, et l’Angoisse atroce, despotique,

Sur mon crâne incliné plante son drapeau noir.

KEMP=MAG – kempis poetry magazine – magazine for art & literature

More in: Baudelaire, Charles

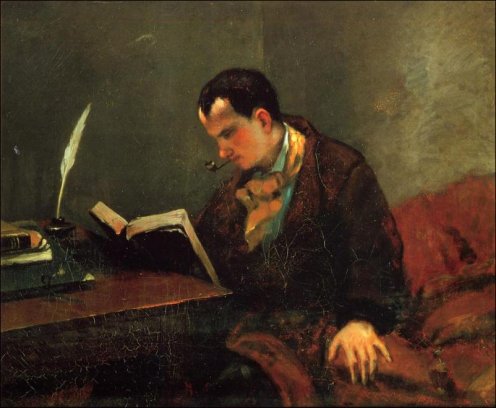

monica richter: il faut dire -jules v. 1963

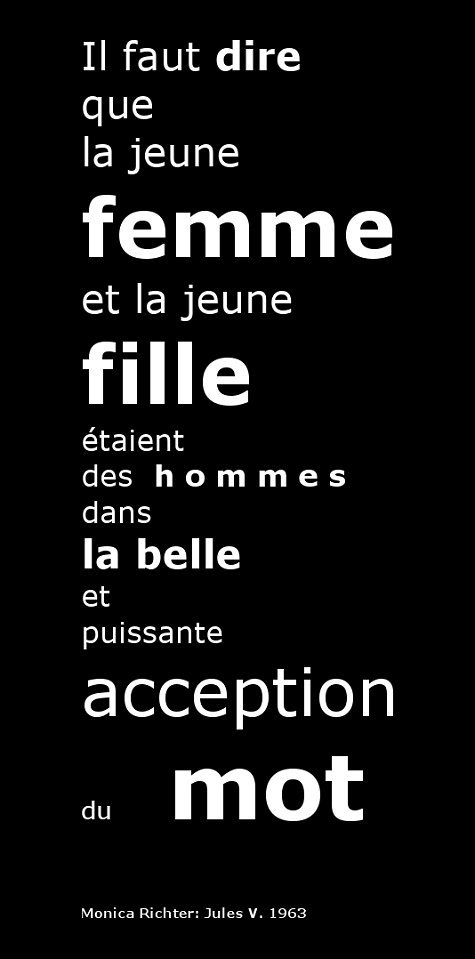

monica richter: no

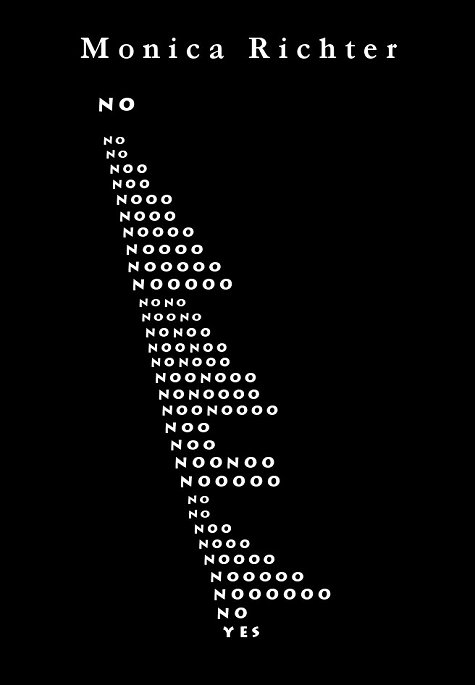

monica richter: allow me – oscar w. 1963

monica richter: nevermore – paul v. 1974

Monica Richter poetry – kempis poetry magazine

More in: *Concrete + Visual Poetry P-T, FLUXUS LEGACY, Monica Richter, Richter, Monica, Visual & Concrete Poetry, ZERO art

Paul Verlaine

(1844-1896)

Vous êtes calme, vous voulez un voeu discret

Vous êtes calme, vous voulez un voeu discret,

Des secrets à mi-voix dans l’ombre et le silence,

Le coeur qui se répand plutôt qu’il ne s’élance,

Et ces timides, moins transis qu’il ne paraît.

Vous accueillez d’un geste exquis telles pensées

Qui ne marchent qu’en ordre et font le moins de bruit.

Votre main, toujours prête à la chute du fruit,

Patiente avec l’arbre et s’abstient de poussées.

Et si l’immense amour de vos commandements

Embrasse et presse tout en sa sollicitude,

Vos conseils vont dicter aux meilleurs et l’étude

Et le travail des plus humbles recueillements.

Le pécheur, s’il prétend vous connaître et vous plaire,

Ô vous qui nous aimant si fort parliez si peu,

Doit et peut, à tout temps du jour comme en tout lieu,

Bien faire obscurément son devoir et se taire,

Se taire pour le monde, un pur sénat de fous,

Se taire sur autrui, des âmes précieuses,

Car nous taire vous plaît, même aux heures pieuses,

Même à la mort, sinon devant le prêtre et vous.

Donnez-leur le silence et l’amour du mystère,

Ô Dieu glorifieur du bien fait en secret,

À ces timides moins transis qu’il ne paraît,

Et l’horreur, et le pli des choses de la terre,

Donnez-leur, ô mon Dieu, la résignation,

Toute forte douceur, l’ordre et l’intelligence,

Afin qu’au jour suprême ils gagnent l’indulgence

De l’Agneau formidable en la neuve Sion,

Afin qu’ils puissent dire : ” Au moins nous sûmes croire ”

Et que l’Agneau terrible, ayant tout supputé,

Leur réponde : ” Venez, vous avez mérité,

Pacifiques, ma paix, et douloureux, ma gloire. ”

Paul Verlaine Poésie

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: *Archive Les Poètes Maudits, Archive U-V, Verlaine, Paul

.jpg)

Willem Kloos

(1859-1938)

Van De Zee

Aan Frederik van Eeden

De Zee, de Zee klotst voort in eindelooze deining,

De Zee waarin mijn ziel zichzelf weerspiegeld ziet;

De Zee is als mijn Ziel in wezen en verschijning,

Zij is een levend Schoon en kent zichzelve niet.

Zij wischt zich zelven af in eeuwige verreining,

En wendt zich altijd om en keert weer waar zij vliedt,

Zij drukt zichzelven uit in duizenderlei lijning

En zingt een eeuwig-blij en eeuwig-klagend lied.

O, Zee was Ik als Gij in al Uw onbewustheid,

Dan zou ik eerst gehéél en gróót-gelukkig zijn;

Dan had ik eerst geen lust naar menschlijke belustheid

Op menschelijke vreugd en menschelijke pijn;

Dan wás mijn Ziel een Zee, en hare zelfgerustheid,

Zou, wijl Zij grooter is dan Gij, nóg grooter zijn.

Hans Hermans Natuurdagboek – maart 2010

► Website Hans Hermans fotografie

Willem Kloos poetry

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Hans Hermans Photos, Kloos, Willem

.jpg)

Rainer Maria Rilke

(1875-1926)

Erinnerung

Und du wartest, erwartest das Eine,

das dein Leben unendlich vermehrt;

das Mächtige, Ungemeine,

das Erwachen der Steine,

Tiefen, dir zugekehrt.

Es dämmern im Bücherständer

die Bände in Gold und Braun;

und du denkst an durchfahrene Länder,

an Bilder, an die Gewänder

wiederverlorener Fraun.

Und da weißt du auf einmal: das war es.

Du erhebst dich, und vor dir steht

eines vergangenen Jahres

Angst und Gestalt und Gebet.

Rainer Maria Rilke: Erinnerung

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive Q-R, Rilke, Rainer Maria

R o b e r t B r o w n i n g

(1812-1889)

Old Pictures in Florence

The morn when first it thunders in March,

The eel in the pond gives a leap, they say;

As I leaned and looked over the aloed arch

Of the villa-gate this warm March day,

No flash snapped, no dumb thunder rolled

In the valley beneath where, white and wide

And washed by the morning water-gold,

Florence lay out on the mountain-side.

River and bridge and street and square

Lay mine, as much at my beck and call,

Through the live translucent bath of air,

As the sights in a magic crystal ball.

And of all I saw and of all I praised,

The most to praise and the best to see

Was the startling bell-tower Giotto raised;

But why did it more than startle me?

Giotto, how, with that soul of yours,

Could you play me false who loved you so?

Some slights if a certain heart endures

Yet it feels, I would have your fellows know!

I’ faith, I perceive not why I should care

To break a silence that suits them best,

But the thing grows somewhat hard to bear

When I find a Giotto join the rest.

On the arch where olives overhead

Print the blue sky with twig and leaf

(That sharp-curled leaf which they never shed)

‘Twixt the aloes, I used to lean in chief,

And mark through the winter afternoons,

By a gift God grants me now and then,

In the mild decline of those suns like moons,

Who walked in Florence, besides her men.

They might chirp and chaffer, come and go

For pleasure or profit, her men alive–

My business was hardly with them, I trow,

But with empty cells of the human hive–

With the chapter-room, the cloister-porch,

The church’s apsis, aisle, or nave,

Its crypt, one fingers along with a torch,

Its face set full for the sun to shave.

Wherever a fresco peels and drops,

Wherever an outline weakens and wanes

Till the latest life in the painting stops,

Stands One whom each fainter pulse-tick pains;

One, wishful each scrap should clutch the brick,

Each tinge not wholly escape the plaster,

–A lion who dies of an ass’s kick,

The wronged great soul of an ancient Master.

For oh, this world and the wrong it does!

They are safe in heaven with their backs to it,

The Michaels and Rafaels, you hum and buzz

Round the works of, you of the little wit!

Do their eyes contract to the earth’s old scope,

Now that they see God face to face,

And have all attained to be poets, I hope?

‘Tis their holiday now, in any case.

Much they reck of your praise and you!

But the wronged great souls–can they be quit

Of a world where their work is all to do,

Where you style them, you of the little wit,

Old Master This and Early the Other,

Not dreaming that Old and New are fellows:

A younger succeeds to an elder brother,

Da Vincis derive in good time from Dellos.

And here where your praise might yield returns,

And a handsome word or two give help,

Here, after your kind, the mastiff girns

And the puppy pack of poodles yelp.

What, not a word for Stefano there,

Of brow once prominent and starry,

Called Nature’s Ape and the world’s despair

For his peerless painting? (See Vasari.)

There stands the Master. Study, my friends,

What a man’s work comes to! So he plans it,

Performs it, perfects it, makes amends

For the toiling and moiling, and then, ‘sic transit’!

Happier the thrifty blind-folk labor,

With upturned eye while the hand is busy,

Not sidling a glance at the coin of their neighbor!

‘Tis looking downward that makes one dizzy.

"If you knew their work you would deal your dole."

May I take upon me to instruct you?

When Greek Art ran and reached the goal,

Thus much had the world to boast ‘in fructu’–

The Truth of Man, as by God first spoken,

Which the actual generations garble,

Was re-uttered, and Soul (which Limbs betoken)

And Limbs (Soul informs) made new in marble.

So you saw yourself as you wished you were,

As you might have been, as you cannot be;

Earth here, rebuked by Olympus there:

And grew content in your poor degree

With your little power, by those statues’ godhead,

And your little scope, by their eyes’ full sway,

And your little grace, by their grace embodied,

And your little date, by their forms that stay.

You would fain be kinglier, say, than I am?

Even so, you will not sit like Theseus.

You would prove a model? The Son of Priam

Has yet the advantage in arms’ and knees’ use.

You’re wroth–can you slay your snake like Apollo?

You’re grieved–still Niobe’s the grander!

You live–there’s the Racers’ frieze to follow:

You die–there’s the dying Alexander.

So, testing your weakness by their strength,

Your meager charms by their rounded beauty,

Measured by Art in your breadth and length,

You learned–to submit is a mortal’s duty.

–When I say "you" ’tis the common soul,

The collective, I mean–the race of Man

That receives life in parts to live in a whole,

And grow here according to God’s clear plan.

Growth came when, looking your last on them all,

You turned your eyes inwardly one fine day

And cried with a start–What if we so small

Be greater and grander the while than they?

Are they perfect of lineament, perfect of stature?

In both, of such lower types are we

Precisely because of our wider nature;

For time, theirs–ours, for eternity.

Today’s brief passion limits their range;

It seethes with the morrow for us and more.

They are perfect–how else? they shall never change;

We are faulty–why not? we have time in store.

The Artificer’s hand is not arrested

With us; we are rough-hewn, nowise polished;

They stand for our copy, and, once invested

With all they can teach, we shall see them abolished.

‘Tis a life-long toil till our lump be leaven–

The better! What’s come to perfection perishes.

Things learned on earth we shall practice in heaven:

Works done least rapidly, Art most cherishes.

Thyself shalt afford the example, Giotto!

Thy one work, not to decrease or diminish,

Done at a stroke, was just (was it not?) "O!"

Thy great Campanile is still to finish.

Is it true that we are now, and shall be hereafter,

But what and where depend on life’s minute?

Hails heavenly cheer or infernal laughter

Our first step out of the gulf or in it?

Shall Man, such step within his endeavor,

Man’s face, have no more play and action

Than joy which is crystallized forever,

Or grief, an eternal petrifaction?

On which I conclude, that the early painters,

To cries of "Greek Art and what more wish you?"–

Replied, "To become now self-acquainters,

And paint man, man, whatever the issue!

Make new hopes shine through the flesh they fray,

New fears aggrandize the rags and tatters:

To bring the invisible full into play!

Let the visible go to the dogs–what matters?"

Give these, I exhort you, their guerdon and glory

For daring so much, before they well did it.

The first of the new, in our race’s story,

Beats the last of the old; ’tis no idle quiddit.

The worthies began a revolution,

Which if on earth you intend to acknowledge,

Why, honor them now! (ends my allocution)

Nor confer your degree when the folk leave college.

There’s a fancy some lean to and others hate–

That, when this life is ended, begins

New work for the soul in another state,

Where it strives and gets weary, loses and wins:

Where the strong and the weak, this world’s congeries,

Repeat in large what they practiced in small,

Through life after life in unlimited series;

Only the scale’s to be changed, that’s all.

Yet I hardly know. When a soul has seen

By the means of Evil that Good is best,

And, through earth and its noise, what is heaven’s serene–

When our faith in the same has stood the test–

Why, the child grown man, you burn the rod,

The uses of labor are surely done;

There remaineth a rest for the people of God;

And I have had troubles enough, for one.

But at any rate I have loved the season

Of Art’s spring-birth so dim and dewy;

My sculptor is Nicolo the Pisan,

My painter–who but Cimabue?

Nor ever was a man of them all indeed,

From these to Ghiberti and Ghirlandajo,

Could say that he missed my critic-meed.

So, now to my special grievance–heigh-ho!

Their ghosts still stand, as I said before,

Watching each fresco flaked and rasped,

Blocked up, knocked out, or whitewashed o’er:

–No getting again what the church has grasped!

The works on the wall must take their chance;

"Works never conceded to England’s thick clime!"

(I hope they prefer their inheritance

Of a bucketful of Italian quicklime.)

When they go at length, with such a shaking

Of heads o’er the old delusion, sadly

Each master his way through the black streets taking,

Where many a lost work breathes though badly–

Why don’t they bethink them of who has merited?

Why not reveal while their pictures dree

Such doom, how a captive might be out-ferreted?

Why is it they never remember me?

Not that I expect the great Bigordi,

Nor Sandro to hear me, chivalric, bellicose;

Nor the wronged Lippino; and not a word I

Say of a scrap of Fra Angelico’s;

But are you too fine, Taddeo Gaddi,

To grant me a taste of your intonaco,

Some Jerome that seeks the heaven with a sad eye?

Not a churlish saint, Lorenzo Monaco?

Could not the ghost with the close red cap,

My Pollajolo, the twice a craftsman,

Save me a sample, give me the hap

Of a muscular Christ that shows the draftsman?

No Virgin by him the somewhat petty,

Of finical touch and tempera crumbly–

Could not Alesso Baldovinetti

Contribute so much, I ask him humbly?

Margheritone of Arezzo,

With the grave-clothes garb and swaddling barret

(Why purse up mouth and beak in a pet so,

You bald old saturnine poll-clawed parrot?)

Not a poor glimmering Crucifixion,

Where in the foreground kneels the donor?

If such remain, as is my conviction,

The hoarding it does you but little honor.

They pass; for them the panels may thrill,

The tempera grow alive and tinglish;

Their pictures are left to the mercies still

Of dealers and stealers, Jews and the English,

Who, seeing mere money’s worth in their prize,

Will sell it to somebody calm as Zeno

At naked High Art, and in ecstasies

Before some clay-cold vile Carlino!

No matter for these! But Giotto, you,

Have you allowed, as the town-tongues babble it–

Oh, never! it shall not be counted true–

That a certain precious little tablet

Which Buonarroti eyed like a lover–

Was buried so long in oblivion’s womb

And, left for another than I to discover,

Turns up at last! and to whom?–to whom?

I, that have haunted the dim San Spirito,

(Or was it rather the Ognissanti?)

Patient on altar-step planting a weary toe!

Nay, I shall have it yet! ‘Detur amanti!’

My Koh-i-noor–or (if that’s a platitude)

Jewel of Giamschid, the Persian Sofi’s eye;

So, in anticipative gratitude,

What if I take up my hope and prophesy?

When the hour grows ripe, and a certain dotard

Is pitched, no parcel that needs invoicing,

To the worse side of the Mont Saint Gothard,

We shall begin by way of rejoicing;

None of that shooting the sky (blank cartridge),

Nor a civic guard, all plumes and lacquer,

Hunting Radetzky’s soul like a partridge

Over Morello with squib and cracker.

This time we’ll shoot better game and bag ’em hot–

No mere display at the stone of Dante,

But a kind of sober Witanagemot

(Ex: "Casa Guidi," ‘quod videas ante’)

Shall ponder, once Freedom restored to Florence,

How Art may return that departed with her.

Go, hated house, go each trace of the Loraine’s,

And bring us the days of Orgagna hither!

How we shall prologuize, how we shall perorate,

Utter fit things upon art and history,

Feel truth at blood-heat and falsehood at zero rate,

Make of the want of the age no mystery;

Contrast the fructuous and sterile eras,

Show–monarchy ever its uncouth cub licks

Out of the bear’s shape into Chimaera’s,

While Pure Art’s birth is still the republic’s.

Then one shall propose in a speech (curt Tuscan,

Expurgate and sober, with scarcely an "issimo,")

To end now our half-told tale of Cambuscan,

And turn the bell-tower’s alt_ to altissimo:

And find as the beak of a young beccaccia

The Campanile, the Duomo’s fit ally,

Shall soar up in gold full fifty braccia,

Completing Florence, as Florence, Italy.

Shall I be alive that morning the scaffold

Is broken away, and the long-pent fire,

Like the golden hope of the world, unbaffled

Springs from its sleep, and up goes the spire

While "God and the People" plain for its motto,

Thence the new tricolor flaps at the sky?

At least to foresee that glory of Giotto

And Florence together, the first am I!

.jpg)

Robert Browning poetry

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Browning, Robert

.jpg)

W i l l i a m S h a k e s p e a r e

(1564-1616)

T H E S O N N E T S

30

When to the sessions of sweet silent thought,

I summon up remembrance of things past,

I sigh the lack of many a thing I sought,

And with old woes new wail my dear time’s waste:

Then can I drown an eye (unused to flow)

For precious friends hid in death’s dateless night,

And weep afresh love’s long since cancelled woe,

And moan th’ expense of many a vanished sight.

Then can I grieve at grievances foregone,

And heavily from woe to woe tell o’er

The sad account of fore-bemoaned moan,

Which I new pay as if not paid before.

But if the while I think on thee (dear friend)

All losses are restored, and sorrows end.

![]()

kempis poetry magazine

More in: -Shakespeare Sonnets

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature