Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

.jpg)

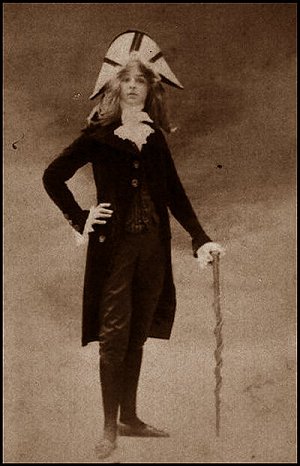

Virginia Woolf

(1882-1941)

Together and Apart

Mrs. Dalloway introduced them, saying you will like him. The conversation began some minutes before anything was said, for both Mr. Serle and Miss Arming looked at the sky and in both of their minds the sky went on pouring its meaning though very differently, until the presence of Mr. Serle by her side became so distinct to Miss Anning that she could not see the sky, simply, itself, any more, but the sky shored up by the tall body, dark eyes, grey hair, clasped hands, the stern melancholy (but she had been told “falsely melancholy”) face of Roderick Serle, and, knowing how foolish it was, she yet felt impelled to say:

“What a beautiful night!”

Foolish! Idiotically foolish! But if one mayn’t be foolish at the age of forty in the presence of the sky, which makes the wisest imbecile—mere wisps of straw—she and Mr. Serle atoms, motes, standing there at Mrs. Dalloway’s window, and their lives, seen by moonlight, as long as an insect’s and no more important.

“Well!” said Miss Anning, patting the sofa cushion emphatically. And down he sat beside her. Was he “falsely melancholy,” as they said? Prompted by the sky, which seemed to make it all a little futile—what they said, what they did—she said something perfectly commonplace again:

“There was a Miss Serle who lived at Canterbury when I was a girl there.”

With the sky in his mind, all the tombs of his ancestors immediately appeared to Mr. Serle in a blue romantic light, and his eyes expanding and darkening, he said: “Yes.

“We are originally a Norman family, who came over with the Conqueror. That is a Richard Serle buried in the Cathedral. He was a knight of the garter.”

Miss Arming felt that she had struck accidentally the true man, upon whom the false man was built. Under the influence of the moon (the moon which symbolized man to her, she could see it through a chink of the curtain, and she took dips of the moon) she was capable of saying almost anything and she settled in to disinter the true man who was buried under the false, saying to herself: “On, Stanley, on”—which was a watchword of hers, a secret spur, or scourge such as middle–aged people often make to flagellate some inveterate vice, hers being a deplorable timidity, or rather indolence, for it was not so much that she lacked courage, but lacked energy, especially in talking to men, who frightened her rather, and so often her talks petered out into dull commonplaces, and she had very few men friends—very few intimate friends at all, she thought, but after all, did she want them? No. She had Sarah, Arthur, the cottage, the chow and, of course THAT, she thought, dipping herself, sousing herself, even as she sat on the sofa beside Mr. Serle, in THAT, in the sense she had coming home of something collected there, a cluster of miracles, which she could not believe other people had (since it was she only who had Arthur, Sarah, the cottage, and the chow), but she soused herself again in the deep satisfactory possession, feeling that what with this and the moon (music that was, the moon), she could afford to leave this man and that pride of his in the Serles buried. No! That was the danger—she must not sink into torpidity—not at her age. “On, Stanley, on,” she said to herself, and asked him:

“Do you know Canterbury yourself?”

Did he know Canterbury! Mr. Serle smiled, thinking how absurd a question it was—how little she knew, this nice quiet woman who played some instrument and seemed intelligent and had good eyes, and was wearing a very nice old necklace—knew what it meant. To be asked if he knew Canterbury. When the best years of his life, all his memories, things he had never been able to tell anybody, but had tried to write—ah, had tried to write (and he sighed) all had centred in Canterbury; it made him laugh.

His sigh and then his laugh, his melancholy and his humour, made people like him, and he knew it, and vet being liked had not made up for the disappointment, and if he sponged on the liking people had for him (paying long calls on sympathetic ladies, long, long calls), it was half bitterly, for he had never done a tenth part of what he could have done, and had dreamed of doing, as a boy in Canterbury. With a stranger he felt a renewal of hope because they could not say that he had not done what he had promised, and yielding to his charm would give him a fresh startat fifty! She had touched the spring. Fields and flowers and grey buildings dripped down into his mind, formed silver drops on the gaunt, dark walls of his mind and dripped down. With such an image his poems often began. He felt the desire to make images now, sitting by this quiet woman.

“Yes, I know Canterbury,” he said reminiscently, sentimentally, inviting, Miss Anning felt, discreet questions, and that was what made him interesting to so many people, and it was this extraordinary facility and responsiveness to talk on his part that had been his undoing, so he thought often, taking his studs out and putting his keys and small change on the dressing–table after one of these parties (and he went out sometimes almost every night in the season), and, going down to breakfast, becoming quite different, grumpy, unpleasant at breakfast to his wife, who was an invalid, and never went out, but had old friends to see her sometimes, women friends for the most part, interested in Indian philosophy and different cures and different doctors, which Roderick Serle snubbed off by some caustic remark too clever for her to meet, except by gentle expostulations and a tear or two—he had failed, he often thought, because he could not cut himself off utterly from society and the company of women, which was so necessary to him, and write. He had involved himself too deep in life—and here he would cross his knees (all his movements were a little unconventional and distinguished) and not blame himself, but put the blame off upon the richness of his nature, which he compared favourably with Wordsworth’s, for example, and, since he had given so much to people, he felt, resting his head on his hands, they in their turn should help him, and this was the prelude, tremulous, fascinating, exciting, to talk; and images bubbled up in his mind.

“She’s like a fruit tree—like a flowering cherry tree,” he said, looking at a youngish woman with fine white hair. It was a nice sort of image, Ruth Anning thought—rather nice, yet she did not feel sure that she liked this distinguished, melancholy man with his gestures; and it’s odd, she thought, how one’s feelings are influenced. She did not like HIM, though she rather liked that comparison of his of a woman to a cherry tree. Fibres of her were floated capriciously this way and that, like the tentacles of a sea anemone, now thrilled, now snubbed, and her brain, miles away, cool and distant, up in the air, received messages which it would sum up in time so that, when people talked about Roderick Serle (and he was a bit of a figure) she would say unhesitatingly: “I like him,” or “I don’t like him,” and her opinion would be made up for ever. An odd thought; a solemn thought; throwing a green light on what human fellowship consisted of.

“It’s odd that you should know Canterbury,” said Mr. Serle. “It’s always a shock,” he went on (the white–haired lady having passed), “when one meets someone” (they had never met before), “by chance, as it were, who touches the fringe of what has meant a great deal to oneself, touches accidentally, for I suppose Canterbury was nothing but a nice old town to you. So you stayed there one summer with an aunt?” (That was all Ruth Anning was going to tell him about her visit to Canterbury.) “And you saw the sights and went away and never thought of it again.”

Let him think so; not liking him, she wanted him to run away with an absurd idea of her. For really, her three months in Canterbury had been amazing. She remembered to the last detail, though it was merely a chance visit, going to see Miss Charlotte Serle, an acquaintance of her aunt’s. Even now she could repeat Miss Serle’s very words about the thunder. “Whenever I wake, or hear thunder in the night, I think ‘Someone has been killed’.” And she could see the hard, hairy, diamond–patterned carpet, and the twinkling, suffused, brown eyes of the elderly lady, holding the teacup out unfilled, while she said that about the thunder. And always she saw Canterbury, all thundercloud and livid apple blossom, and the long grey backs of the buildings.

The thunder roused her from her plethoric middleaged swoon of indifference; “On, Stanley, on,” she said to herself; that is, this man shall not glide away from me, like everybody else, on this false assumption; I will tell him the truth.

“I loved Canterbury,” she said.

He kindled instantly. It was his gift, his fault, his destiny.

“Loved it,” he repeated. “I can see that you did.”

Her tentacles sent back the message that Roderick Serle was nice.

Their eyes met; collided rather, for each felt that behind the eyes the secluded being, who sits in darkness while his shallow agile companion does all the tumbling and beckoning, and keeps the show going, suddenly stood erect; flung off his cloak; confronted the other. It was alarming; it was terrific. They were elderly and burnished into a glowing smoothness, so that Roderick Serle would go, perhaps to a dozen parties in a season, and feel nothing out of the common, or only sentimental regrets, and the desire for pretty images—like this of the flowering cherry tree—and all the time there stagnated in him unstirred a sort of superiority to his company, a sense of untapped resources, which sent him back home dissatisfied with life, with himself, yawning, empty, capricious. But now, quite suddenly, like a white bolt in a mist (but this image forged itself with the inevitability of lightning and loomed up), there it had happened; the old ecstasy of life; its invincible assault; for it was unpleasant, at the same time that it rejoiced and rejuvenated and filled the veins and nerves with threads of ice and fire; it was terrifying. “Canterbury twenty years ago,” said Miss Anning, as one lays a shade over an intense light, or covers some burning peach with a green leaf, for it is too strong, too ripe, too full.

Sometimes she wished she had married. Sometimes the cool peace of middle life, with its automatic devices for shielding mind and body from bruises, seemed to her, compared with the thunder and the livid appleblossom of Canterbury, base. She could imagine something different, more like lightning, more intense. She could imagine some physical sensation. She could imagine——

And, strangely enough, for she had never seen him before, her senses, those tentacles which were thrilled and snubbed, now sent no more messages, now lay quiescent, as if she and Mr. Serle knew each other so perfectly, were, in fact, so closely united that they had only to float side by side down this stream.

Of all things, nothing is so strange as human intercourse, she thought, because of its changes, its extraordinary irrationality, her dislike being now nothing short of the most intense and rapturous love, but directly the word “love” occurred to her, she rejected it, thinking again how obscure the mind was, with its very few words for all these astonishing perceptions, these alternations of pain and pleasure. For how did one name this. That is what she felt now, the withdrawal of human affection, Serle’s disappearance, and the instant need they were both under to cover up what was so desolating and degrading to human nature that everyone tried to bury it decently from sight—this withdrawal, this violation of trust, and, seeking some decent acknowledged and accepted burial form, she said:

“Of course, whatever they may do, they can’t spoil Canterbury.”

He smiled; he accepted it; he crossed his knees the other way about. She did her part; he his. So things came to an end. And over them both came instantly that paralysing blankness of feeling, when nothing bursts from the mind, when its walls appear like slate; when vacancy almost hurts, and the eyes petrified and fixed see the same spot—a pattern, a coal scuttle—with an exactness which is terrifying, since no emotion, no idea, no impression of any kind comes to change it, to modify it, to embellish it, since the fountains of feeling seem sealed and as the mind turns rigid, so does the body; stark, statuesque, so that neither Mr. Serle nor Miss Anning could move or speak, and they felt as if an enchanter had freed them, and spring flushed every vein with streams of life, when Mira Cartwright, tapping Mr. Serle archly on the shoulder, said:

“I saw you at the Meistersinger, and you cut me. Villain,” said Miss Cartwright, “you don’t deserve that I should ever speak to you again.”

And they could separate.

.jpg)

Virginia Woolf: A Haunted House, and other short stories

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive W-X, Archive W-X, Woolf, Virginia

Renée Vivien

(1877-1909)

Roses du soir

Des roses sur la mer, des roses dans le soir,

Et toi qui viens de loin, les mains lourdes de roses !

J’aspire ta beauté. Le couchant fait pleuvoir

Ses fines cendres d’or et ses poussières roses…

Des roses sur la mer, des roses dans le soir.

Un songe évocateur tient mes paupières closes.

J’attends, ne sachant trop ce que j’attends en vain,

Devant la mer pareille aux boucliers d’airain,

Et te voici venue en m’apportant des roses…

Ô roses dans le ciel et le soir ! Ô mes roses !

Sommeil

Ô Sommeil, ô Mort tiède, ô musique muette !

Ton visage s’incline éternellement las,

Et le songe fleurit à l’ombre de tes pas,

Ainsi qu’une nocturne et sombre violette.

Les parfums affaiblis et les astres décrus

Revivent dans tes mains aux pâles transparences

Évocateur d’espoirs et vainqueur de souffrances

Qui nous rends la beauté des êtres disparus.

Sonnet de porcelaine

Le soir, ouvrant au vent ses ailes de phalène,

Évoque un souvenir fragilement rosé,

Le souvenir, touchant comme un Saxe brisé,

De ta naïveté fraîche de porcelaine.

Notre chambre d’hier, où meurt la marjolaine,

N’aura plus ton regard plein de ciel ardoisé,

Ni ton étonnement puéril et rusé…

Ô frissons de ta nuque où brûlait mon haleine !

Et mon coeur, dont la paix ne craint plus ton retour,

Ne sanglotera plus son misérable amour,

Frêle apparition que le silence éveille !

Loin du sincère avril de venins et de miels,

Tu souris, m’apportant les fleurs de ta corbeille,

Fleurs précieuses des champs artificiels.

.jpg)

Renée Vivien poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Vivien, Renée

.jpg)

Ton van Reen

DE EZELIN

Op haar afgetrapte poten

staat de ezelin voor de kar

haar rug altijd in afweer strak

om de klappen op te vangen

Haar huid vol slordig haar

hangt om haar heen als een halflege zak

bij gebrek aan voedsel eet ze van haar poten

bij gebrek aan water drinkt ze stof

ze wordt veracht om haar moed

geminacht om haar ijver

gehaat voor haar trouw

geslagen voor haar werklust

ze is veroordeeld tot werken

tot de dood erop volgt

Haar jong wordt van haar weggehaald

nog voor het gezoogd is

Ton van Reen: De naam van het mes. Afrikaanse gedichten

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: -De naam van het mes, Ton van Reen

![]()

Literaire Podia Amsterdam,

GRAP en Sugar Factory presenteren

VERSE BEATS

internationaal poëzie & hiphop programma

Op vrijdag 28 januari 2011 in de Sugar Factory te Amsterdam: dichters, slammers, mc’s en musici uit verschillende Europese landen. Zij brengen in een gevarieerd programma poëzie, freestyle, slam en spoken word. Aanvang 20.00 uur.

VERSE BEATS brengt poetry en hiphop bij elkaar. Dichters dragen voor, freestylers reageren hierop. Er is ruimte voor cross-overs, confrontaties worden niet geschuwd. Naast dichters als H.H. ter Balkt, F. Starik, Hagar Peeters en Christine Otten staan onder andere hiphoppers Rico en Typhoon met de live band Muppetstuff op het podium. Uit het buitenland komen speciaal voor VERSE BEATS de Franse slammer/dichter Jean-Luc Despax, de Engelse dichter Ryan Van Winkle en uit Duitsland dichter Matthias Göritz en rapper Gauner. Het thema van de avond is De Stad.

In het sfeervolle decor van nachttheater Sugar Factory soleert de een na de ander: Christine Otten presenteert met Jan Klug muzikale poëzie; Simon Mulder draagt een sonnet voor; rappers/freestylers Surya, Robian en Frits van Dijk reageren al improviserend op voordrachten van de dichters en slammers. De beats komen van DJ Clean Cut. Rap wordt poëzie met hiphopper Rico in de rol van observeerder en Typhoon als filosofisch denker. De presentatie van de avond is in handen van The Change Agent en Gauner.

Aan VERSE BEATS werken mee: H.H. ter Balkt, Jean-Luc Despax (FR), Matthias Göritz (DE), Rico, Typhoon & Muppetstuff, Ryan Van Winkle (UK), F. Starik, Surya, Tjitse Hofman, Hagar Peeters, Mowaffk Al-Sawad, Simon Mulder, Christine Otten met Jan Klug, Dennis Gaens, Robian, Frits van Dijk, dj Clean Cut.

VERSE BEATS is een initiatief van de Literaire Podia Amsterdam (LPA) in samenwerking met GRAP en de Sugar Factory.

VERSE BEATS wordt mede mogelijk gemaakt door de LPA, GRAP, Sugar Factory, Nederlands Letterenfonds, SNS Reaalfonds.

De LPA bestaat uit: AIDA, British Council, Castrum Peregrini, El Hizjra, Feest der Poëzie, Goethe-Institut, John Adams Institute, Maison Descartes, Openbare Bibliotheek, Ons Suriname, Perdu, SLAA, School der Poëzie.

Vrijdag 28 januari 2011

Sugar Factory

Lijnbaansgracht 238, Amsterdam

Entree: € 9,- (studenten: € 7,50)

Tijd: 20.00 – 00:00 uur

www.sugarfactory.nl

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Art & Literature News, Peeters, Hagar, Poetry Slam

Paul Boldt

(1885-1921)

DIE DIRNE

Die Zähne standen unbeteiligt, kühl

Gleich Fischen an den heißen Sommertagen.

Sie hatte sie in sein Gesicht geschlagen

Und trank es – trank – entschlossen dies Gefühl

In sich zu halten, denn sie ward ein wenig

Wie früher Mädchen und erlitt Verführung;

Er aber spürte bloß Berührung,

Den Mund wie einen Muskel, mager, sehnig.

Und sollte glauben an ihr Offenbaren,

Und sah, wie sie dann dastand – spiegelnackt –

Das Falsche, das Frisierte an den Haaren;

Und unwillig auf ihren schlechten Akt

Schlug er das Licht aus, legte sich zu ihr,

Mischend im Blut Entsetzen mit der Gier.

Paul Boldt poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Boldt, Paul, Expressionism

![]()

Renée Vivien

(1877-1909)

A la femme aimée

Lorsque tu vins, à pas réfléchis, dans la brume,

Le ciel mêlait aux ors le cristal et l’airain.

Ton corps se devinait, ondoiement incertain,

Plus souple que la vague et plus frais que l’écume.

Le soir d’été semblait un rêve oriental

De rose et de santal.

Je tremblais. De longs lys religieux et blêmes

Se mouraient dans tes mains, comme des cierges froids.

Leurs parfums expirants s’échappaient de tes doigts

En le souffle pâmé des angoisses suprêmes.

De tes clairs vêtements s’exhalaient tour à tour

L’agonie et l’amour.

Je sentis frissonner sur mes lèvres muettes

La douceur et l’effroi de ton premier baiser.

Sous tes pas, j’entendis les lyres se briser

En criant vers le ciel l’ennui fier des poètes

Parmi des flots de sons languissamment décrus,

Blonde, tu m’apparus.

Et l’esprit assoiffé d’éternel, d’impossible,

D’infini, je voulus moduler largement

Un hymne de magie et d’émerveillement.

Mais la strophe monta bégayante et pénible,

Reflet naïf, écho puéril, vol heurté,

Vers ta Divinité.

Renée Vivien poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive U-V, Vivien, Renée

.jpg)

William Shakespeare

(1564-1616)

THE SONNETS

62

Sin of self-love possesseth all mine eye,

And all my soul, and all my every part;

And for this sin there is no remedy,

It is so grounded inward in my heart.

Methinks no face so gracious is as mine,

No shape so true, no truth of such account,

And for my self mine own worth do define,

As I all other in all worths surmount.

But when my glass shows me my self indeed

beated and chopt with tanned antiquity,

Mine own self-love quite contrary I read:

Self, so self-loving were iniquity.

‘Tis thee (my self) that for my self I praise,

Painting my age with beauty of thy days.

![]()

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: -Shakespeare Sonnets

Edith Södergran

(1892-1923)

Rêves Dangereux

Ne t’approche pas trop de tes rêves :

Ce sont fumée qui peut se disperser –

Ils sont dangereux et peuvent demeurer.

As-tu regardé tes rêves dans les yeux :

ils sont malades et ne comprennent rien –

Ils n’ont que leurs propres pensées.

Ne t’approche pas trop de tes rêves :

Ce sont mensonges, ils devraient s’en aller –

Ce sont folie qui veut rester.

Edith Södergran poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Södergran, Edith

Delmira Agustini

(1886-1914)

Explosión

Si la vida es amor, bendita sea!

Quiero más vida para amar! Hoy siento

Que no valen mil años de la idea

Lo que un minuto azul del sentimiento.

Mi corazon moria triste y lento…

Hoy abre en luz como una flor febea;

La vida brota como un mar violento

Donde la mano del amor golpea!

Hoy partio hacia la noche, triste, fría

Rotas las alas mi melancolía;

Como una vieja mancha de dolor

En la sombra lejana se deslíe…

Mi vida toda canta, besa, ríe!

Mi vida toda es una boca en flor!

Delmira Augustini poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Agustini, Delmira, Archive A-B

.jpg)

Ton van Reen

EEN HOND IS AARDE

Leer de hond geen ketting kennen

als hij huilt kerven messen zijn huid

messen voor trouw

Leer de hond geen stenen kennen

als hij loopt rammelt zijn maag

stenen voor brood

Leer de hond geen zand kennen

als hij ligt stuift het zand uit zijn keel

zand voor water

Een hond is aarde

Ton van Reen: De naam van het mes. Afrikaanse gedichten

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: -De naam van het mes, Ton van Reen

.jpg)

Amy Levy

(1861-1889)

Epitaph

(On a Commonplace Person Who Died in Bed)

THIS is the end of him, here he lies:

The dust in his throat, the worm in his eyes,

The mould in his mouth, the turf on his breast;

This is the end of him, this is best.

He will never lie on his couch awake,

Wide-eyed, tearless, till dim daybreak.

Never again will he smile and smile

When his heart is breaking all the while.

He will never stretch out his hands in vain

Groping and groping–never again.

Never ask for bread, get a stone instead,

Never pretend that the stone is bread.

Never sway and sway ‘twixt the false and true,

Weighing and noting the long hours through.

Never ache and ache with chok’d-up sighs;

This is the end of him, here he lies.

Amy Levy poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Amy Levy, Archive K-L, Levy, Amy

A case of identity:

Nadja

jef van kempen 2011

fleursdumal.nl magazine

from: ► Museum of lost concepts

More in: Jef van Kempen, Jef van Kempen Photos & Drawings, Photography

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature