Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

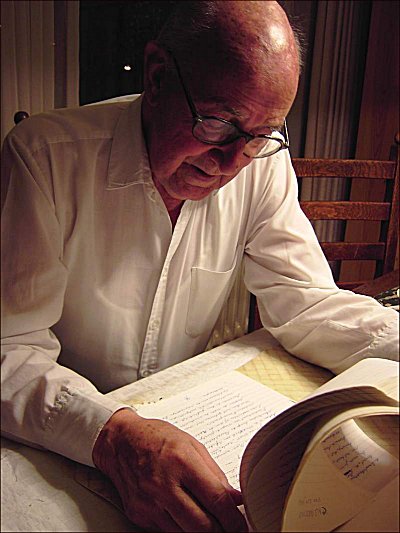

In Memoriam Anton (Toon) Eijkens

(1920-2012)

Anton Eijkens schreef de Tilburgse historie in 1000 dichtregels

TILBURG – In het verzorgingshuis Koningsvoorde is afgelopen zaterdagochtend Antonius Maria Eijkens overleden. Toon Eijkens heeft diverse boeken op zijn naam staan en schreef ook de Tilburgse rijmkroniek die burgemeester Jan van de Mortel in 1946 bij zijn afscheid aangeboden kreeg van de Tilburgse bevolking. Het beschrijft de geschiedenis van Tilburg in duizend dichtregels.

Eijkens werd in 1920 te Tilburg geboren en volgde het gymnasium op het St. Odulphuslyceum waar hij zich al vroeg ontpopte als een jongeman met talent voor taal en muziek én als dichter. Zijn vader vond een baan voor hem bij Bureau Van Spaendonck. Het stond zijn literaire ambities niet in de weg. Onder de naam Anton Eijkens schreef hij artikelen en verhalen in de bladen Brabantia Nostra en Edele Brabant, waar hij ook in de redactie zat.

In 1946 beleefde Anton Eijkens zijn productiefste jaar. Hij publiceerde toen onder meer de verhalenbundel Rond de toren, de bloemlezing De Sprookjeshoorn en Een handvol verzen. Bovendien schreef hij samen met Jan Naaijkens het scenario en de teksten voor het massale openluchtspel Kruis en Ploeg dat in de zomer van 1946 bij gelegenheid van het 50-jarig bestaan van de Noord-Brabantse Christelijke Boerenbond (NBC) opgevoerd werd in het Willem II-stadion. Kort erna werd aan burgemeester Van de Mortel het gedenkboek Rijmkroniek van Tilburg, het hart van Brabant aangeboden, een uniek in kalfsleer gebonden boek waarvan de door Eijkens geschreven tekst geheel gekalligrafeerd was door zijn zwager Kees Mandos.

Ook in de daarop volgende jaren bleef Eijkens actief als schrijver, zij het vooral van gelegenheidsliederen voor zijn collega’s en van gedenkboeken voor het bedrijfsleven en voor Bureau Van Spaendonck zelf. Daar nam hij in 1984 afscheid als secretaris van diverse werkgeversorganisaties en directeur van de Sector Secretariaten.

Toon Eijkens was getrouwd met Thea Mandos met wie hij zeven kinderen kreeg. In 1982 werd hij geridderd in de Orde van Oranje Nassau.

Anton Eijkens

(1920-2012)

Voor de Beminde

Mijn liederen zijn gering als schaamle kinderen,

die voor een aalmoes komen zingen aan je raam,

als ‘t daglicht in de straat begint te minderen

en aan de avondlucht de eerste sterren staan.

Wie zal mij in mijn schamelheid verhinderen

mijn leed en vreugd te komen zingen aan je raam?

Ik weet: jij kunt het lied van schaamle kinderen

niet zonder mildheid langs je venster laten gaan.

Ontmoeting

Ik had maar de kortste weg genomen,

een weg vol distels en woekerkruid,

want de avond viel dichter in de bomen

en de wind blies langzaam de sterren uit.

Maar aan de rand van een bloeiende tuin,

geurend van appels, pruimen en peren,

blies een bultenaar op zijn kranke bazuin;

“Kunt gij het geluk uw rug toekeren?”

Hoe vreemd: teruggaand heb ik genomen

de langste weg, langs de hoogste bomen.

Anton Eijkens: Twee gedichten

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive E-F, Eijkens, Anton, In Memoriam

Georg Heym (1887-1912) Von toten Städten . . . Von toten Städten ist das Land bedecket, Wie Kränze hängt der Efeu von den Zinnen. Und manchmal eine Glocke rufet innen. Und trüber Fluß rundum die Mauer lecket. Im halben Licht, das aus den Wolken schweifet, Im Abend gehn die traurigen Geleite Auf Wegen kahl, in schwarzen Flor geschlagen, Die Blumen trocken in den Händen tragen. Sie stehen draußen in verlorner Weite, Ein Haufe schüchtern bei den großen Grüften. Noch einmal weht die Sonne aus den Lüften, Und malt wie Feuer rot die Angesichter. Georg Heym poetry fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive G-H, Expressionism, Georg Heym, Heym, Georg

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (19)

Shoot! (Si Gira, 1926) The Notebooks of Serafino Gubbio, Cinematograph Operator by Luigi Pirandello. Translated from the Italian by C. K. Scott Moncrieff

BOOK IV

2

We were waiting to-day, beneath the pergola of the tavern, for the arrival of a certain “young lady of good family,” recommended by Bertini, who was to take a small part in a film which has been left for some months unfinished and which they now wish to complete.

More than an hour had passed since a boy had been sent on a bicycle to this young lady’s house, and still there was no sign of anyone, not even of the boy returning.

Polacco was sitting with me at one table, the Nestoroff and Carlo Ferro were at another. All four of us, with the young lady we were expecting, were to go in a motor-car for a “nature scene” in the Bosco Sacro.

The sultry afternoon heat, the nuisance of the myriad flies of the tavern, the enforced silence among us four, obliged to remain together notwithstanding the openly declared and for that matter obvious aversion felt by the other two for Polacco and also for myself, increased the strain of waiting until it became quite intolerable.

The Nestoroff was obstinately restraining herself from turning her eyes in our direction. But she was certainly aware that I was looking at her, covertly, while apparently paying her no attention; and more than once she had shewn signs of annoyance. Carlo Ferro had noticed this and had knitted his brows, keeping a close watch on her; and then she had pretended for his benefit to be annoyed, not indeed by myself who was looking at her, but by the sun which, through the vine leaves of the pergola, was beating upon her face. It was true; and a wonderful sight was the play, on that face, of the purple shadows, straying and shot with threads of golden sunlight, which lighted up now one of her nostrils, and part of her upper lip, now the lobe of her ear and a patch of her throat.

I find myself assailed, at times, with such violence by the external aspects of things that the clear, outstanding sharpness of my perceptions almost terrifies me. It becomes so much a part of myself, what I see with so sharp a perception, that I am powerless to conceive how in the world a given object–thing or person–can be other than what I would have it be. The Nestoroff’s aversion, in that moment of such intensely lucid perception, was intolerable to me. How in the world did she not understand that I was not her enemy?

Suddenly, after peering out for a little through the trellis, she rose, and we saw her stroll out, towards a hired carriage, which also had been standing there for an hour outside the entrance to the Kosmograph, waiting under the blazing sun. I too had noticed the carriage; but the foliage of the vine prevented me from seeing who was waiting in it. It had been waiting there for so long that I could not believe that there was anybody in it. Polacco rose; I rose also, and we looked out.

A young girl, dressed in a sky-blue frock, of Swiss material, very light, with a straw hat, trimmed with black velvet ribbons, sat waiting in the carriage. Holding in her lap an aged dog with a shaggy coat, black and white, she was timidly and anxiously watching the taximeter of the carriage, which every now and then gave a click, and must already be indicating a considerable sum. The Nestoroff went up to her with great civility and invited her to come inside, to escape from the rays of the sun. Would it not be better to wait beneath the pergola of the tavern?

“Plenty of flies, of course. But at any rate one can sit in the shade.”

The shaggy dog had begun to growl at the Nestoroff, baring its teeth in defence of its young mistress. She, turning suddenly crimson, perhaps at the unexpected pleasure of seeing this beautiful lady shew an interest in her with such courtesy; perhaps also from the annoyance that her stupid old pet was causing her, which received the other’s cordial invitation in so unfriendly a spirit, thanked her, accepted the invitation with some confusion, and stepped down from the carriage with the dog under her arm. I had the impression that she left the carriage chiefly to make amends for the old dog’s hostile reception of the lady. And indeed she slapped it hard on the muzzle with her hand, calling out:

“Be quiet, Piccini!”

And then, turning to the Nestoroff:

“I apologise for her, she doesn’t understand. . . . “

And they came in together beneath the pergola. I studied the old dog which was angrily looking its young mistress up and down, with the eyes of a human being. It seemed to be saying to her: “And what do ‘you’ understand?”

Polacco, in the mean time, had advanced towards her and was asking politely:

“Signorina Luisetta?”

She turned a deep crimson, as though lost in a painful surprise, at being recognised by some one whom she did not know; smiled; nodded her head in the affirmative, and all the black ribbons on her straw hatnodded with her.

Polacco went on to ask her:

“Is Papa here?”

Yes, once more, with her head, as though amid her blushes and confusion she could not find words with which to answer. At length, with an effort, she found a timid utterance:

“He went inside some time ago: he said that he would have finished his business at once, and now . . . “

She raised her eyes to look at the Nestoroff and smiled at her, as though she were sorry that this gentleman with his questions had distracted her attention from the lady, who had been so kind to her without even knowing who she was. Polacco thereupon introduced them:

“Signorina Luisetta Cavalena; Signora Nestoroff.”

He then turned and beckoned to Carlo Ferro, who at once sprang to his feet and bowed awkwardly.

“Carlo Ferro, the actor.”

Last of all, he introduced me:

“Gubbio.”

It seemed to me that, among the lot of us, I was the one who frightened her least.

I knew by repute Cavalena, her father, notorious at the Kosmograph by the nickname of ‘Suicide’. It seems that the poor man is terribly oppressed by a jealous wife. Owing to his wife’s jealousy he has been obliged to renounce first of all a commission in the Militia, as Surgeon Lieutenant, and one good practice after another; then, his independent work, as well, and journalism, in which he had found an opening, and finally teaching also, to which he had turned in desperation, in the technical schools, as a lecturer on physics and natural history. Now, not being able (still on account of his wife) to devote himself to the drama, for which he has for some time past believed himself to have a distinct talent, he has turned to the composition of scenarios for the cinematograph, with great loathing, ‘obtorto collo’, in order to supply the wants of his family, since they are unable to live exclusively upon his wife’s fortune, and what little they make by letting a pair of furnished rooms. Unfortunately, in the hell of his home life, having now grown accustomed to viewing the world as a prison, it seems that, however hard he may try, he can never succeed in composing a plot for a film without dragging in,

somewhere or other, a suicide. Which accounts for Polacco’s having steadily, up to the present, rejected all his scenarios, in view of the fact that the English decline, absolutely, to hear of a suicide in their films.

“Has he come to see me?” Polacco asked Signorina Luisetta.

Signorina Luisetta stammered in confusion:

“No,” she said… “I don’t think so; Bertini, I think it was.”

“Ah, the rascal! He has gone to Bertini, has he? But tell me, Signorina, did he go in alone?”

Fresh, and still more vivid blushes on the part of Signorina Luisetta.

“With Mamma.”

Polacco threw up his hands and waved them in the air, pulling a long face and winking.

“Let us hope that nothing dreadful is going to happen!”

Signorina Luisetta made an effort to smile; and echoed:

“Let us hope so . . . “

And it hurt me so to see her smile like that, with her little face aflame! I would have liked to shout at Polacco:

“Stop tormenting her with these questions! Can’t you see that you are making her utterly miserable?”

But Polacco, all of a sudden, had an idea; he clapped his hands:

“Why shouldn’t we take Signorina Luisetta? By Jove, yes; we have been waiting here for the last hour! Why yes, of course. My dear young lady, you will be helping us out of a difficulty, and you will see that we shall give you plenty of fun. It will all be over in half an hour. I shall tell the porter, as soon as your father and mother come out, to let them know that you have gone for half an hour with me and this lady and gentleman. I am such a friend of your father that I can venture to take the liberty. I shall give you a little part to play, you will like that?”

Signorina Luisetta had evidently a great fear of appearing timid, embarrassed, foolish; and, as for coming with us, said: “Why not?” But, when it came to acting, she could not, she did not know how . . . and in those clothes, too–really? . . . she had never tried . . . she felt ashamed . . . besides . . .

Polacco explained to her that nothing serious was required: she would not have to open her mouth, nor to mount a stage, nor to appear before the public. Nothing at all. It would be in the country. Among the trees. “Without a word spoken.

“You will be sitting on a bench, beside this gentleman,” he pointed to Ferro. “This gentleman will pretend to be making love to you. You, naturally, do not believe him, and laugh at him. … Like that…. Splendid! You laugh and shake your head, plucking the petals off a flower. All of a sudden, a motor-car dashes up. This gentleman starts to his feet, frowns, looks round him, scenting danger in the air. You stop plucking at the flower and adopt an attitude of doubt, dismay. Suddenly this lady,” here he pointed to the Nestoroff, “jumps down from the car, takes a revolver from her muff and fires at you . . . “

Signorina Luisetta opened her eyes wide and stared at the Nestoroff, in terror.

“In make-believe! Don’t be frightened!” Polacco went on with a smile. “The gentleman runs forward, disarms the lady; meanwhile you have sunk down, first of all, on the bench, mortally wounded; from the bench you fall to the ground–without hurting yourself, please! and it is all over…. Come, come, don’t let us waste any more time! We can rehearse the scene on the spot; you will see, it will go off splendidly … and what a fine present you will get afterwards from the Kosmograph!”

“But if Papa . . . “

“We shall leave a message for him!”

“And Piccini?”

“We can take her with us; I shall carry her myself…. You will see, the Kosmograph will give Piccini a fine present too . . . . Come along, let us be off!”

As we got into the motor-car (again, I am certain, so as not to appear timid and foolish), she, who had not given me a second thought, looked at me doubtfully.

Why was I coming too! What part was I to play?

No one had uttered a word to me; I had been barely introduced, named as a dog might be; I had not opened my mouth; I remained silent . . . .

I noticed that my silent presence, the necessity for which she failed to see, but which impressed her, nevertheless, as being mysteriously necessary, was beginning to disturb her. No one thought of offering her any explanation; I could not offer her one myself. I had seemed to her ‘a person like the rest’; or rather, at first sight, a person ‘more akin to herself’ than the rest. Now she was beginning to be aware that for these other people and also for herself (in a vague way) I was not, properly speaking, a person. She began to feel that my person was not necessary; but that my presence there had the necessity of a ‘thing’, which she as yet did not understand; and that I remained silent for that reason. They might speak, yes, they, all four of them–because they were people, each of them represented a person, his or her own; but I, no: I was a thing: why, perhaps the thing that was resting on my knees, wrapped in a black cloth.

And yet I too had a mouth to speak with, eyes to see with, and the said eyes, look, were shining as they rested on her; and certainly within myself I felt . . .

Oh, Signorina Luisetta, if you only knew the joy that his own feelings were affording the person– ‘not necessary’ as such, but as a thing–who sat opposite to you! Did it occur to you that I–albeit seated in front of you like that, like a thing–was capable of feeling within myself? Perhaps. But what I was feeling, behind my mask of impassivity, that you certainly could not imagine.

Feelings that were ‘not necessary’, Signorina Luisetta! You do not know what they are, nor do you know the intoxicating joy that they can give! This machine here, for instance: does it seem to you that there can be any necessity for it to feel? There cannot be! If it could feel, what feelings would it have? Not necessary feelings, surely.

Something that was a luxury for it. Fantastic things . . . .

Well, among the four of you, to-day, I–a pair of legs, a lap, and on it a machine–I felt ‘fantastically’.

You, Signorina Luisetta, were, with everything round about you, contained in my feelings, which rejoiced in your innocence, in the pleasure that you derived from the breeze in your face, the view of the open country, the proximity of the beautiful lady. Does it seem strange to you that you entered like that, with everything round about you, into my feelings? But may not a beggar by the roadside perhaps see the road and all the people who go past, comprised in that feeling of pity which he seeks to arouse? You, being more sensitive than the rest, as you pass, notice that you enter into his feeling, and stop and give him the charity of a copper. Many others do not enter in, and it does not occur to the beggar that they are outside his feeling, inside another of their own, in which he too is included as a shadowy nuisance; the beggar thinks that they are hard-hearted. What was I to you in your feelings, Signorina Luisetta î A mysterious man? Yes, you are quite right. Mysterious. If you knew how I feel, at certain moments, my ‘inanimate silence’! And I revel in the mystery that is exhaled by this silence for such as are capable of remarking it. I should like never to speak at all; to receive everyone and everything in this silence of mine, every tear, every smile; not to provide, myself, an echo to the smile; I could not; not to wipe away, myself, the tear; I should not know how; but so that all might find in me, not only for their griefs, but also and even more for their joys, a tender pity that would make us brothers if only for a moment.

I am so grateful for the good that you have done with the freshness of your timid, smiling innocence, to the lady who was sitting by your side! So at times, when the rain does not come, parched plants find refreshment in a breath of air. And this breath of air you yourself were, for a moment, in the burning desert of the feelings of that woman who sat beside you; a burning desert that does not know the refreshing coolness of tears.

At one point she, looking at you almost with a frightened admiration, took your hand in her own and stroked it. Who knows what bitter envy of you was torturing her heart at that moment?

Did you see how, immediately afterwards, her face darkened?

A cloud had passed . . . . What cloud?

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (19)

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: -Shoot!, Pirandello, Luigi

Glasscherven op een muur

Eens zaten jullie om jenever heen en wijn maar

jullie moesten kapot, van fles naar gruzelementen.

Iemand heeft jullie ooit fluitend in cement gestoken.

Gedacht: ‘Wat ben jij mooi stuk, glas, ik zal jou naar

het westen laten wijzen. Het beste lijkt me dat voor

jou, doorzichtig groen.’ Daar steek je nu van noen tot noen,

van winter tot winter. In oude handschoenen uw splinters.

Bert Bevers

(Verschenen in Stroom, nummer 24, Antwerpen, lente 2007)

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Bevers, Bert

Elizabeth (Lizzie) Siddal

(1829-1862)

True Love

Farewell, Earl Richard,

Tender and brave;

Kneeling I kiss

The dust from thy grave.

Pray for me, Richard,

Lying alone

With hands pleading earnestly,

All in white stone.

Soon must I leave thee

This sweet summer tide;

That other is waiting

To claim his pale bride.

Soon I’ll return to thee

Hopeful and brave,

When the dead leaves

Blow over thy grave.

Then shall they find me

Close at thy head

Watching or fainting,

Sleeping or dead.

Elizabeth (Lizzie) Siddal poems

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Lizzy Siddal, Siddal, Lizzy

William Shakespeare

Sonnet 130

My mistress’ eyes are nothing like the sun,

Coral is far more red, than her lips red,

If snow be white, why then her breasts are dun:

If hairs be wires, black wires grow on her head:

I have seen roses damasked, red and white,

But no such roses see I in her cheeks,

And in some perfumes is there more delight,

Than in the breath that from my mistress reeks.

I love to hear her speak, yet well I know,

That music hath a far more pleasing sound:

I grant I never saw a goddess go,

My mistress when she walks treads on the ground.

And yet by heaven I think my love as rare,

As any she belied with false compare.

William Shakespeare

Sonnet 130

Geen zonlicht gloeit in ‘t oog van wie ik hou,

Nooit wordt haar liprood met koraal verward,

Is sneeuw soms wit, dan zijn haar borsten grauw,

Is hoofdhaar draad, dan zijn haar draden zwart;

Gevlamde rozen ken ik, rood en wit,

Maar haar wang toont geen roos die zo ontluikt,

Er zijn parfums waar zoeter geur in zit

Dan waar de adem van mijn lief naar ruikt.

Al houd ik van haar stem, ik zie goed in,

Muziekklank zweeft veel aangenamer rond;

‘t Is waar, gaan zag ik nooit nog een godin,

Als mijn lief wandelt treedt ze op de grond.

En toch, bij God, ik acht mijn lief zo hoog,

Als elke vrouw bedot met vals vertoog.

(nieuwe vertaling Cornelis W. Schoneveld, mei 2012)

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: -Shakespeare Sonnets, Shakespeare

Nick J. Swarth

Babyscherven (barsten als die jongens)

Hij werd onthoofd door een tunnel.

Het was de enige keer dat ik hem zag

blèren. Bloed.

Zijn poriën openden zich. In de kleinste

stond een fiedelkast van toen.

Als je wilt huilen moet je het nu doen,

zei niemand in het bijzonder tot iemand

zonder naam.

De jongens waren mooi destijds, ik ook.

De herder van de wacht had een glanzende vacht.

De lege hal was leeg, minimaal een minuut, maar

ogenschijnlijk een eeuw.

De roltrappen rolden en ratelden ongerijmd.

Ik was blijven zitten TOEVALLIG

bij haar pakken, haar zakken, haar zooi.

En zij DE BEDELGRIJS gaf me bij terugkeer,

een kleine drie kwartier na haar vertrek, twee

dollar.

You’ve been keeping an eye on it, good!

De haan kraait, de kraai moet worden gegeten

ANDERS ZOU IK HET OOK NIET WETEN

Om de hoek een man.

Volgens hem liet hij de baby per ongeluk vallen.

Boodschappen stapelen de vaat.

Waarom doen. Morgen is alles weer vies.

(uit: Nick J. Swarth: MIJN ONSTERFELIJKE LEVER. Gedichten & tekeningen. Uitgeverij IJzer, Utrecht | 2012. ISBN 978 90 8684 086 1 – NUR 305 – Paperback, 64 blz. Prijs: € 10 – Zie voor meer informatie: www.swarth.nl )

Op YouTube een video-opname van de presentatie van de nieuwe bundel Mijn onsterfelijke lever

Nick J. Swarth poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Swarth, Nick J.

Theodor Fontane

(1819–1898)

Im Garten

Die hohen Himbeerwände

Trennten dich und mich,

Doch im Laubwerk unsre Hände

Fanden von selber sich.

Die Hecke konnt’ es nicht wehren,

Wie hoch sie immer stund:

Ich reichte dir die Beeren,

Und du reichtest mir deinen Mund.

Ach, schrittest du durch den Garten

Noch einmal im raschen Gang,

Wie gerne wollt’ ich warten,

Warten stundenlang.

Theodor Fontane poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive E-F, Theodor Fontane

William Shakespeare

(1564-1616)

THE SONNETS

130

My mistress’ eyes are nothing like the sun,

Coral is far more red, than her lips red,

If snow be white, why then her breasts are dun:

If hairs be wires, black wires grow on her head:

I have seen roses damasked, red and white,

But no such roses see I in her cheeks,

And in some perfumes is there more delight,

Than in the breath that from my mistress reeks.

I love to hear her speak, yet well I know,

That music hath a far more pleasing sound:

I grant I never saw a goddess go,

My mistress when she walks treads on the ground.

And yet by heaven I think my love as rare,

As any she belied with false compare.

![]()

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: -Shakespeare Sonnets

Vinko Kalinić

Pola pjesme

Probudio sam se jutros s pola pjesme u glavi

pamtim, sanjao sam te – da, bile su to tvoje usne

i ruke! i nos! i uho! – i mogao bih napisati pjesmu

sasvim strašnu neku pjesmu, pristojnu i zanosnu

recimo, o čovjeku koji je umro u snu, ljubeći te

ali ne znam kako ti oči pretočiti u riječi

te strašne oči koje me uvijek iz nova prepolove

na mene koji bi umro zbog njih

i na mene koji bi umro bez njih

– oči, pred kojima ni jedna pjesma

nikada neće biti ispjevana do kraja

Komiža, 20. 11. 2010

Half a song

I woke up this morning with half a song in my head

I remember, I dreamt about you – yes, those were your lips

and hands! and nose! and ear! – and I could write a song

some absolutely dreadful song, decent and passionate

let’s say, about a man who died in his dream, while kissing you

but I don’t know how to transfuse your eyes into words,

those enticing eyes which bisect me in two all over again,

to a me that would die for them

and to a me that would die without them

– those eyes, in front of which no song

will ever be sung till the end

Translation by Darko Kotevski, Melbourne

Vinko Kalinić poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive K-L, Kalinić, Vinko

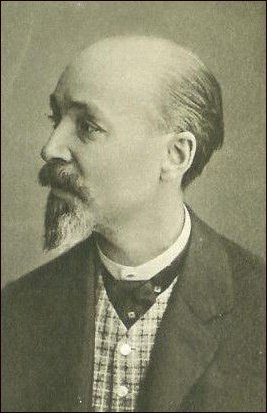

Marie Krysinka

(1845-1908)

Le démon de Racoczi

A Ringel

C’était par une après-midi embrumée

Dans l’air opaque le ciel pesait comme un remords.

J’avais dans l’âme le tentissement de son dernier baiser; –

Je l’avais pour jamais enfoui au fond de l’âme

Comme au fond d’un caveau sépulcral.

Dans l’air opaque le ciel pesait comme un remords.

• • •

Alors pour fuir cette obsédante mélancolie de l’air et du ciel – j’ai fermé la fenêtre brusquement.

J’ai fermé la fenêtre et j’ai tiré le rideau épais qui soudainement plongea la chambre dans une lumière lourde.

Une artificielle lumière.

Plus ardente et plus molle que la triste lumière de l’air embrumé,

• • •

Et les objets prirent des attitudes inaccoutumées.

Des attitudes du rêve.

Dans la caverne de l’ombre, le piano allumait le ricanement de ses dents blanches.

Les fauteuils – ainsi que des personnes cataleptiques – étendaient leurs bras raides.

Les luisances voilées des bronzes semblaient des clignements d’yeux craintifs.

Et, dans l’or des cadres se réveillaient des lucioles; –

Auprès des glaces qui ouvraient dans le mur d’inquiétantes perspectives.

Et près de la bibliothèque, le Démon de Racoczi attira mes regards irrésistiblement…

C’était une simple eau-forte où, sur un fond brouillé, se détachait en noir exagéré – le Démon aux joues creuses, à la lèvre crispée par une gaieté féroce, ou peut-être par quelque affreuse torture.

Mais ce n’était qu’une simple eau-forte.

Puis le pli entre les sourcils froncés s’accentua.

Il s’accentua, – bien que la chose paraisse incroyable, –

Il se creusa plus profondément,

Figeant une expression d’angoisse farouche, sur cette face au sinistre rictus;

Les cheveux se hérissèrent à n’en pas douter;

Et l’archet que tenait la main du Démon eut un frémissement, s’anima, – en vérité, – et fit rendre à l’instrument un son,

Un son jamais entendu jusqu’alors. –

Et si triste, qu’il semblait fait de tous les sanglots et de tous les glas.

Et aussi doux que le parfum des tubéreuses, flottant dans la crépusculaire clarté des soirs.

Puis l’archet s’élança furieux, avec un grondement de rafale, sur les cordes désespérées.

Et c’était comme des cris de détresse, comme des rires de fous et comme des râles d’agonisants.

Et c’était comme des appels éperdus, de suprêmes appels, hurlés vers le ciel désert.

Mais l’horrible symphonie décrut ainsi qu’une mer qui s’apaise.

Et sour l’archet du Démon s’épanouit alors tout un orchestre;

S’épanouit alors comme une grande fleur – tout un orchestre.

Les violons traînaient des notes pâmées, et parfois miaulaient comme des chats.

Les flûtes éclataient de petits rires nerveux.

Les violoncelles chantaient comme des voix humaines.

La valse déchaînait son tournoyant délire.

Rythmée comme par des soupirs d’amour;

Chuchoteuse comme les flots,

Et aussi mélancolique qu’un adieu;

Désordonnée, incohérente, avec des éclats de cristal qu’on brise;

Essoufflée, rugissante comme une tempête;

Puis alanguie, lassée, s’apaisant dans une lueur de bleu lunaire.

Et par l’archet du Démon évoqués,

Les Souvenirs passaient;

Cortège muet,

En robes blanches et nimbés d’or, les Souvenirs radieux, les bon et purs Souvenirs;

Sous leurs longs voiles de deuil, les douloureuses Ressouvenances;

Les ombres des Amours morts passaient couronnées de fleurs desséchées.

L’archet s’arrêta avec un grincement sourd.

Le Démon était toujours devant moi avec son sinistre rictus;

Mais ce n’était vraiment qu’une simple eau-forte.

Dans l’air opaque, le ciel pesait comme un remords.

1er novembre 1882

(Recueil : “Rythmes pittoresques”)

Marie Krysinka poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive K-L

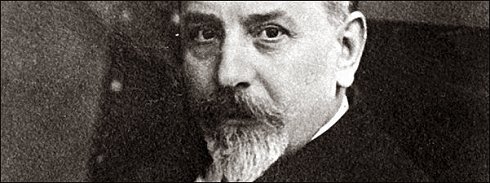

Max Elskamp

(1862-1931)

La femme

Mais maintenant vient une femme,

Et lors voici qu’on va aimer,

Mais maintenant vient une femme

Et lors voici qu’on va pleurer,

Et puis qu’on va tout lui donner

De sa maison et de son âme,

Et puis qu’on va tout lui donner

Et lors après qu’on va pleurer

Car à présent vient une femme,

Avec ses lèvres pour aimer,

Car à présent vient une femme

Avec sa chair tout en beauté,

Et des robes pour la montrer

Sur des balcons, sur des terrasses,

Et des robes pour la montrer

A ceux qui vont, à ceux qui passent,

Car maintenant vient une femme

Suivant sa vie pour des baisers,

Car maintenant vient une femme,

Pour s’y complaire et s’en aller.

Max Elskamp poetry

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive E-F, Archive E-F, Elskamp, Max

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature