Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

Gerard Manley Hopkins

(1844 – 1889)

The Alchemist in the City

My window shews the travelling clouds,

Leaves spent, new seasons, alter’d sky,

The making and the melting crowds:

The whole world passes; I stand by.

They do not waste their meted hours,

But men and masters plan and build:

I see the crowning of their towers,

And happy promises fulfill’d.

And I – perhaps if my intent

Could count on prediluvian age,

The labours I should then have spent

Might so attain their heritage,

But now before the pot can glow

With not to be discover’d gold,

At length the bellows shall not blow,

The furnace shall at last be cold.

Yet it is now too late to heal

The incapable and cumbrous shame

Which makes me when with men I deal

More powerless than the blind or lame.

No, I should love the city less

Even than this my thankless lore;

But I desire the wilderness

Or weeded landslips of the shore.

I walk my breezy belvedere

To watch the low or levant sun,

I see the city pigeons veer,

I mark the tower swallows run

Between the tower-top and the ground

Below me in the bearing air;

Then find in the horizon-round

One spot and hunger to be there.

And then I hate the most that lore

That holds no promise of success;

Then sweetest seems the houseless shore,

Then free and kind the wilderness,

Or ancient mounds that cover bones,

Or rocks where rockdoves do repair

And trees of terebinth and stones

And silence and a gulf of air.

There on a long and squared height

After the sunset I would lie,

And pierce the yellow waxen light

With free long looking, ere I die.

Gerard Manley Hopkins poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive G-H, Hopkins, Gerard Manley

George Sand

(1804-1876)

À Aurore

La nature est tout ce qu’on voit,

Tout ce qu’on veut, tout ce qu’on aime.

Tout ce qu’on sait, tout ce qu’on croit,

Tout ce que l’on sent en soi-même.

Elle est belle pour qui la voit,

Elle est bonne à celui qui l’aime,

Elle est juste quand on y croit

Et qu’on la respecte en soi-même.

Regarde le ciel, il te voit,

Embrasse la terre, elle t’aime.

La vérité c’est ce qu’on croit

En la nature c’est toi-même.

George Sand poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive S-T, George Sand

William Shakespeare

(1564-1616)

THE SONNETS

Sonnet 144

Two loves I have of comfort and despair,

Which like two spirits do suggest me still,

The better angel is a man right fair:

The worser spirit a woman coloured ill.

To win me soon to hell my female evil,

Tempteth my better angel from my side,

And would corrupt my saint to be a devil:

Wooing his purity with her foul pride.

And whether that my angel be turned fiend,

Suspect I may, yet not directly tell,

But being both from me both to each friend,

I guess one angel in another’s hell.

Yet this shall I ne’er know but live in doubt,

Till my bad angel fire my good one out.

![]()

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: -Shakespeare Sonnets

![]()

Mijn liefste meisje

Willoos is de vlieger

die meevaart op zonnestralen

naar een rimpelrode branding

van oud geworden licht

Mijn meisje bij zee;

ommuurd met sterfelijkheid

heb ik je zandkastelen, je zijgende beelden

van ridders en prinsessen

Ik ben jou, je vlieger,

je zonlicht; vrees de dagen

zonder zandsculpturen en sprookjesfiguren

die gespeend van jou en mij zullen zijn

Niels Landstra

Niels Landstra presenteert dichtbundel: Waterval

Donderdag 20 september zal Niels Landstra zijn nieuwe dichtbundel Waterval presenteren bij Selexyz Gianotten in Breda, de Barones 63. De aanvang is 19.00 uur.

Na het verschijnen van het kort verhaal ‘Het portret’ in e-zine Meander in 2004, volgde een lange reeks publicaties (korte verhalen, poëzie en interviews) in diverse literaire tijdschriften in zowel Nederland als Vlaanderen. Het oeuvre van Niels Landstra is dan ook rijk, bevat elementen als liefde en dood, geloof en noodlot, en het nemen van afscheid, zoals in zijn gedicht Mijn liefste meisje: ‘Ik ben jou, je vlieger, je zonlicht; vrees de dagen zonder zandsculpturen en sprookjesfiguren die gespeend van jou en mij zullen zijn’.

Naast zijn gedichten en verhalen, schreef hij drie romans en een novelle, waar deze elementen sterk in verweven zijn en die een melancholische sfeer oproepen, maar ook een wrange vorm van humor kennen; deze vertelwijze maakt zijn werk dan ook boeiend tot de laatst gelezen letter.

Zijn dichtbundel ‘Waterval’ bij uitgeverij Oorsprong is zijn debuut als dichter.

Volgend jaar zal Niels Landstra’s eerste roman ‘De vereerder’ verschijnen bij uitgeverij Beefcake Publishing in Gent, België.

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive K-L, Landstra, Niels

Norbert de Vries

Kemp natuurlijk (IV)

Pierre (1 december 1886- 21 juli 1967) en Mathias (31 december 1890- 7 augustus 1964) waren beide autodidact.

Van de lagere school ging het linea recta naar de fabriek. In hun geval was dat de Société Céramique. Die enorm grote fabriek is een jaar of tien gelden gesloopt, en nu ligt daar een prachtige, nieuwe stadswijk. Inderdaad, de wijk Céramique.

Pierre en Math werkten er als plateelschilder.

Het is bijna ongelooflijk om te zien hoe beide jongelieden zich ontwikkeld hebben.

In de lijn van hun dagelijkse werk is hun inschrijving als leerling van het Stadstekeninstituut.

Pierre schilderde er vijf jaar (1906-1911), samen met onder anderen Jan Grégoire en Henri Jonas (die voor een loopbaan in de beeldend kunst zouden kiezen), en het is niet overdreven om Pierre op een met hen vergelijkbaar artistiek niveau te stellen. Pierre Kemp is beroemd geworden als dichter, maar hij heeft enige tijd zeer serieus gewerkt aan een carrière als kunstschilder.

En dan: zijn echte, zijn grote droom was het om componist te worden.

De beide broers kwamen uit een volstrekt niet intellectueel of artistiek milieu, ze hadden weinig onderwijs genoten, en toch hebben ze alle twee erg veel bereikt op het terrein van het geschreven woord. Ze kregen daarvoor ook de alleszins verdiende maatschappelijke erkenning.

Voor me ligt het dossier 1823 (niet openbaar). Een dossier over Koninklijke Onderscheidingen.

Over Math zit er méér in dan over Pierre. Math wordt ook eerder onderscheiden dan Pierre. Je krijgt als lezer van de stukken (na meer dan 50 jaar) ook de indruk dat Math in Maastricht meer gezien was dan Pierre.

We schrijven oktober 1950.

Er heeft zich een Mathias Kemp-Comité gevormd, met lokale zwaargewichten als dr. H. van Can, drs. J. Notermans en mr. Drs. H. Wouters.

Het comité heeft op 19 oktober een gesprek gehad met burgemeester mr. W. Baron Michiels van Kessenich met het oogmerk te bevorderen dat aan Mathias Kemp bij gelegenheid van zijn zestigste verjaardag een KO wordt verleend.

Op 7 november zendt het comité een uitgewerkte levensbeschrijving (4 pagina’s). Voorts geeft Jef Notermans een 5 bladzijden omvattende beschouwing ten beste over ‘Mathias Kemp en de BeNeLux-gedachte. Ook is er een curriculum vitae opgesteld met een opsomming daarbij van ’s mans vele publicaties (poëzie, proza, toneel, uitgaven op cultureel, historisch en sociaal-economisch gebied).

Indrukwekkend. Er is werkelijk flink werk van gemaakt.

De burgemeester heeft er eveneens zichtbaar zorg aan besteed: de concept-brief heeft hij op diverse punten gecorrigeerd en aangepast. En hoe snel handelt hij: de voordracht gaat op 10 november 1950 de deur uit.

Het is voor iemand die de procedures kent geen verrassing: een uitreiking van de onderscheiding op 31 december 1950 is niet haalbaar gebleken. Het wordt uiteindelijk 12 maart 1951. Behoorlijk snel, toch nog.

De brief van het Ministerie van Onderwijs, Kunsten en Wetenschappen is van 6 maart 1951, ondertekend door mr. J. Cals.

Kennelijk kent hij Math Kemp, ‘letterkundige en journalist’, persoonlijk, want de burgemeester wordt nadrukkelijk gevraagd Kemp namens hem te feliciteren.

De geridderde Math was, veel meer dan Pierre, een bekende Limburger.

In 1913 stapte hij van het plateel schilderen over naar de journalistiek. Opmerkelijk dat iemand zoiets lukt. Dan moet je toch over veel talent beschikken. Maar kennelijk zonder enig probleem nam hij de redactie van het weekblad De Maastrichter Krant op zich, en onderscheidde hij zich door het schrijven van vlammende artikelen tegen de expansieneigingen van het Duitse keizerrijk.

Tijdens de Eerste Wereldoorlog is hij de eerste bibliothecaris van de katholieke bibliotheek van Maastricht.

In 1920 wordt hij hoofdredacteur van het weekblad Limburgs Leven (het eerste tijdschrift van algemene strekking in dit landsdeel!), later opgevolgd door De Nedermaas.

Math is op allerlei journalistiek en publicitair vlak actief. Hij vervult voor kortere of langere tijd diverse functies: secretaris van de Kamer van Koophandel, redacteur voor de provincie Limburg van De Maasbode, hoofdredacteur van dagblad De Nieuwe Venlosche Courant, directeur en firmant van de boekhandel en uitgeverij Veldeke te Maastricht, correspondent van De Tijd en Het Algemeen Dagblad, en, sinds 1933, eigenaar en beheerder van het Limburgs antiquariaat en uitgeverij Veldeke.

Op 10 mei 1940 wordt hij gegijzeld door de Duitsers, en is daarmee een van de eerste politieke gevangenen in Nederland!

(mooi detail: burgemeester Michiels van Kessenich moest in mei 1940 van de Duitsers een lijstje van tien vooraanstaande Maastrichtenaren opstellen. Deze mensen golden dan als gijzelaar, ‘als waarborg voor de rustige houding van de Maastrichtenaren’. Van Kessenich gaf, zonder iemand te consulteren, de namen van tien intimi of (kaart)vrienden van hem. Natuurlijk had hij zichzelf bovenaan dat lijstje moeten plaatsen, maar hij verzuimde dat.

Zijn vrienden hebben die weinig dappere houding niet erg gewaardeerd. Kort na de bevrijding van ons land moest er een nieuw kabinet worden geformeerd, en Van Kessenich zou daarin minister worden. Op het laatste moment ging dat niet door. Algemeen wordt inmiddels aangenomen dat die gijzelaarskwestie daar de oorzaak van is geweest.

Overigens is geen der gijzelaars, onder wie dus Math Kemp, een haar gekrenkt tijdens de oorlog.)

In 1951 wordt Math Ridder in de Orde van Oranje-Nassau. En zijn geniale broer? Die moet wachten tot zijn zeventigste verjaardag.

Op 30 januari 1956 schrijft de toenmalige wethouder van onderwijs, kunsten en wetenschappen, Fons Baeten (inderdaad, de latere burgemeester van Maastricht) een korte nota aan de burgemeester, waaruit ik volgende regels citeer:

“Op 1 december van dit jaar zal, zo dit God belieft, de dichter Pierre Kemp zeventig jaar worden. Deze in wezen weinig belangrijke gebeurtenis lijkt mij een gerede aanleiding om de persoon en het werk van deze dichter tot voorwerp van bijzondere belangstelling voor de overheid te maken.

Ik koester het plan de stad Maastricht te interesseren in de uitgave van een gedichtencyclus die de dichter onlangs in regeringsopdracht wijdde aan Maastricht. Nadere voorstellen dienaangaande zullen het College eerlang bereiken. (…..) Een overzicht van leven en werk van de dichter, van de hand van Fernand M. de Louvick (Fernand Lodewick) diene ter adstructie van mijn en eventueel Uw verzoek.”

Het overzicht van De Louvick sluit op pagina 3 af met de zin: “Volgens onze mening is Pierre Kemp niet alleen een dichter die in de hedendaagse Nederlandse literatuur tot de merkwaardigste (sic!) en beste (sic!) gerekend moet worden, maar beweegt hij zich in zijn verzen op een wat men noemen kan Europees peil.”

Middelbare school, vak Nederlands: Literaire kunst van Lodewick. Ik denk dat ik het nog grotendeels van buiten ken. Wat mooi om deze Lodewick zovele jaren nadien nog op een taalfoutje te kunnen betrappen.

Het jaar 1956 is voor Pierre echt een feestjaar geworden.

Hij ontvangt de Constantijn Huygensprijs, en in Maastricht is er onder voorzitterschap van Jef Notermans een werk-comité actief om de ‘dichter-schilder Pierre Kemp’ een passende hulde te brengen, onder meer met een expositie van een paar dozijn van zijn schilderijen in de zalen van de Jan van Eyck-Academie.

” . . . zal in de maand december kunstcritici en minnaars van een kleurrijk palet de overtuiging schenken, dat Pierre Kemp als picturale nazaat van Graafland en Jonas een eervolle plaats inneemt tussen oudere en jongere beoefenaars van Apelles’ kunst.”.

Trouwens, in 1956 verschijnt de bundel Engelse Verfdoos, volgens velen zijn beste werk.

Op 1 december 1956 ontvangt Pierre het Ridderkruis in de Orde van Oranje-Nassau.

Vlak voor zijn dood zal hij, op 30 april 1967, worden bevorderd tot Officier in de Orde van Oranje-Nassau. Het gaat allemaal in grote haast. In het dossier een handgeschreven, ongedateerde notitie:

De heer P. Kemp wordt verpleegd in het ziekenhuis. Naar mededeling van zoon Kemp komt P. Kemp niet meer thuis. Hart en longen zijn zeer zwak.

Norbert de Vries: Kemp natuurlijk (IV)

Mijmeringen over Pierre Kemp uit mijn Maastrichtse tijd

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Kemp, Pierre, Norbert de Vries

Een Egyptische weduwe

bij het schilderij van Lawrence Alma-Tadema

Wij weten nu dat deze schilder wist

dat eeuwen her zich deze dode

als een mummie naar de toekomst wrong

in uitgeleefde luchten en vluchtte

in hiernamaalsen waarin hij zelf

geloofde. Ter plekke zong de twijfel:

men roofde graven leeg en zweeg en

daarom neuriet er de hoop dat

rust hier mag gaan heersen.

De weduwe treurt diep maar ondertussen

leert ze van het sterven: het lot

vermomt zich graag als einde.

Bert Bevers

(uit Afglans – Gedichten 1972-1997, Uitgeverij WEL, Bergen op Zoom, 1997)

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Bevers, Bert

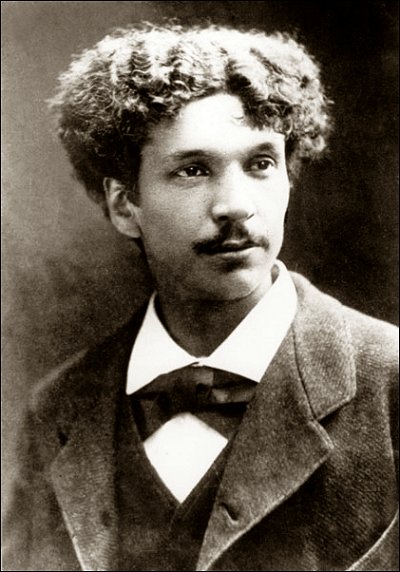

Charles Cros

(1842-1888)

Testament

Si mon âme claire s’éteint

Comme une lampe sans pétrole,

Si mon esprit, en haut, déteint

Comme une guenille folle,

Si je moisis, diamantin,

Entier, sans tache, sans vérole,

Si le bégaiement bête atteint

Ma persuasive parole,

Et si je meurs, soûl, dans un coin

C’est que ma patrie est bien loin

Loin de la France et de la terre.

Ne craignez rien, je ne maudis

Personne. Car un paradis

Matinal, s’ouvre et me fait taire.

Charles Cros poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive C-D, Cros, Charles

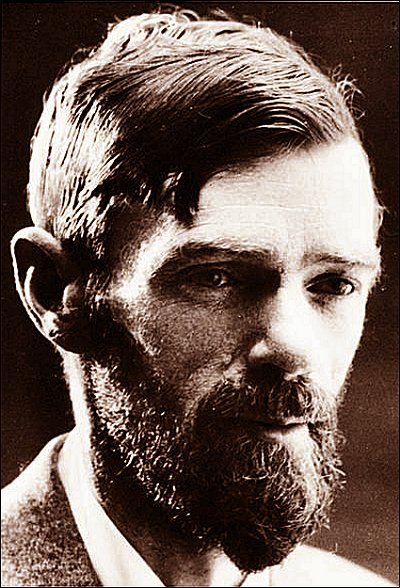

D. H. Lawrence

(1885-1930)

The Elephant is Slow to Mate

The elephant, the huge old beast,

is slow to mate;

he finds a female, they show no haste

they wait

for the sympathy in their vast shy hearts

slowly, slowly to rouse

as they loiter along the river-beds

and drink and browse

and dash in panic through the brake

of forest with the herd,

and sleep in massive silence, and wake

together, without a word.

So slowly the great hot elephant hearts

grow full of desire,

and the great beasts mate in secret at last,

hiding their fire.

Oldest they are and the wisest of beasts

so they know at last

how to wait for the loneliest of feasts

for the full repast.

They do not snatch, they do not tear;

their massive blood

moves as the moon-tides, near, more near

till they touch in flood.

D.H. Lawrence poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive K-L, D.H. Lawrence, Lawrence, D.H.

foto joost bataille

Esther Porcelijn

Bloemlezen en Koffiedik kijken

op de Roze Maandag

Lights On

Daar gaan we Weer Weer WEER Weer.

Zonder ideeën ben ik er niet

Zonder ideeën zijn jullie er niet

Zonder de mensen is er niks

om over te praten.

Zonder verschillen kunnen we alles

stilzwijgend ondergaan.

Dan gaan de lichten op de dimstand.

De grootste beren op de Roze rots,

Komrij’s Paralymics.

Het anders-zijn wordt juist benadrukt?

Met z’n allen in een draaimolen,

de carrousel.

Alle plaatjes van mensen in de centrifuge

tot oliebolsap.

Allemaal hetzelfde,

behalve op Roze maandag.

Nog een Keer Keer KEER Keer.

Online bashen, inmaken oprotten optiefen onder de lakens houden, achter de voordeur. “Mij maakt het niet uit hoor,” als ze maar niet ehm zoenen op straat, ehm handen vasthouden, ehm genegenheid tonen, ehm mij aankijken, ehm iets roze-achtigs doen, ehm of denken, ehm ademen, of ehm leven.

“Het is een ziekte,”

“homo’s zijn dierlijk.”

Nieuw Nieuw NIEUW Nieuw

Oproer uit de jaren 50.

Conservatisme is de allergrootste traditie.

Misplaatste frustratie

van anoniem-schreeuwers is

de online munitie

waar we met z’n allen in draaien.

Zij met de grootste aannames nemen

nooit iets aan van anderen,

want dat is een no-Go Go GO Go.

Dansers in kooien, harde sex, slappe handjes,

roze boa’s, darkrooms.

Cliché Cliché CLICHÉ Cliché.

Niet te verdragen.

Erger nog dan Jonge Sla.

Gay. What’s in a name?

Mo money mo homo mo homo mo homo

Geld waard.

Straks mis je nog de Bootsma.

Geld waard, twee voor de prijs van

Één Één ÉÉN Één.

Benadruk het anders zijn,

anders doet niemand het,

gaan de lichten op dimstand.

Zwieren en draaien.

Daar gaan We We WE We

Weer Weer WEER Weer.

Het evenement ‘Roze Maandag’ maakt onderdeel uit van de Tilburgse Kermis, juli 2012. Het gedicht ‘Bloemlezen en Koffiedik kijken op de Roze Maandag’ werd eerder gepubliceerd in het Brabants Dagblad.

esther porcelijn poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive O-P, Archive O-P, LGBT+ (lhbt+), Porcelijn, Esther

Students

‘Hoest?’

‘Vet en jij?’

‘Ook, wat gaan we doen?’

‘Appie H, knoeipakket scoren, knoeien bij mij?’

‘Doen we, cool’

‘Hé Joris join us’

‘Super, wat gaan we doen?’

‘Barbeknoeitje bij Menno’

‘Vet, let’s do it’

‘Scoor ik snel effe wat grolsies thuis, merkt Bart to nie’

‘Ik zeg doen’

‘Me too’

‘CU’

‘Catch you later boys’

Freda Kamphuis

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive K-L, Kamphuis, Freda

![]()

Valeria

Het zand onder haar boetseert

De naakte deining van haar lijf

Die onder haar weg spoelt, als zij

omkeert. Het gezonken beeld leert

mij haar te lezen: ze smaakt naar zout,

en is er even, de minnares

die mijn momenten leent. Oud

maar slaafs volg ik haar met een krans

van doorns in mijn haar, het is spelen

met mijn wil. Blauw en groot zijn haar

ogen als de zeven hemelen

die zij bestijgt; haar beeldenaar

mag ik zijn. Haar verkondigen

en afstaan. Zolang ze zondig

is en mijn vergeving zich richt

op haar stil en licht bewegen.

Niels Landstra

Niels Landstra presenteert dichtbundel: Waterval

Donderdag 20 september zal Niels Landstra zijn nieuwe dichtbundel Waterval presenteren bij Selexyz Gianotten in Breda, de Barones 63. De aanvang is 19.00 uur.

Na het verschijnen van het kort verhaal ‘Het portret’ in e-zine Meander in 2004, volgde een lange reeks publicaties (korte verhalen, poëzie en interviews) in diverse literaire tijdschriften in zowel Nederland als Vlaanderen. Het oeuvre van Niels Landstra is dan ook rijk, bevat elementen als liefde en dood, geloof en noodlot, en het nemen van afscheid, zoals in zijn gedicht Mijn liefste meisje: ‘Ik ben jou, je vlieger, je zonlicht; vrees de dagen zonder zandsculpturen en sprookjesfiguren die gespeend van jou en mij zullen zijn’.

Naast zijn gedichten en verhalen, schreef hij drie romans en een novelle, waar deze elementen sterk in verweven zijn en die een melancholische sfeer oproepen, maar ook een wrange vorm van humor kennen; deze vertelwijze maakt zijn werk dan ook boeiend tot de laatst gelezen letter.

Zijn dichtbundel ‘Waterval’ bij uitgeverij Oorsprong is zijn debuut als dichter.

Volgend jaar zal Niels Landstra’s eerste roman ‘De vereerder’ verschijnen bij uitgeverij Beefcake Publishing in Gent, België.

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive K-L, Landstra, Niels

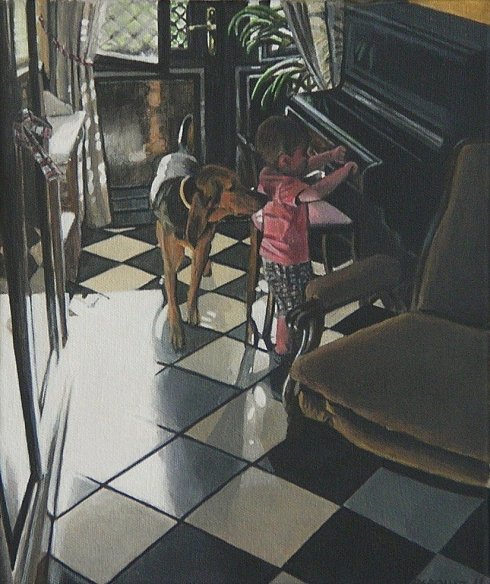

Vincent Berquez© painting:

My son the musician

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Berquez, Vincent, Vincent Berquez

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature