Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

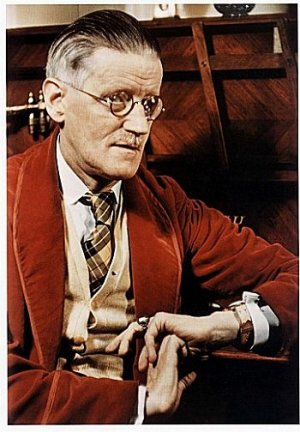

James Joyce

(1882-1941)

A Painful Case

Mr. James Duffy lived in Chapelizod because he wished to live as far as possible from the city of which he was a citizen and because he found all the other suburbs of Dublin mean, modern and pretentious. He lived in an old sombre house and from his windows he could look into the disused distillery or upwards along the shallow river on which Dublin is built. The lofty walls of his uncarpeted room were free from pictures. He had himself bought every article of furniture in the room: a black iron bedstead, an iron washstand, four cane chairs, a clothes-rack, a coal-scuttle, a fender and irons and a square table on which lay a double desk. A bookcase had been made in an alcove by means of shelves of white wood. The bed was clothed with white bedclothes and a black and scarlet rug covered the foot. A little hand-mirror hung above the washstand and during the day a white-shaded lamp stood as the sole ornament of the mantelpiece. The books on the white wooden shelves were arranged from below upwards according to bulk. A complete Wordsworth stood at one end of the lowest shelf and a copy of the Maynooth Catechism, sewn into the cloth cover of a notebook, stood at one end of the top shelf. Writing materials were always on the desk. In the desk lay a manuscript translation of Hauptmann’s Michael Kramer, the stage directions of which were written in purple ink, and a little sheaf of papers held together by a brass pin. In these sheets a sentence was inscribed from time to time and, in an ironical moment, the headline of an advertisement for Bile Beans had been pasted on to the first sheet. On lifting the lid of the desk a faint fragrance escaped, the fragrance of new cedarwood pencils or of a bottle of gum or of an overripe apple which might have been left there and forgotten.

Mr. Duffy abhorred anything which betokened physical or mental disorder. A medival doctor would have called him saturnine. His face, which carried the entire tale of his years, was of the brown tint of Dublin streets. On his long and rather large head grew dry black hair and a tawny moustache did not quite cover an unamiable mouth. His cheekbones also gave his face a harsh character; but there was no harshness in the eyes which, looking at the world from under their tawny eyebrows, gave the impression of a man ever alert to greet a redeeming instinct in others but often disappointed. He lived at a little distance from his body, regarding his own acts with doubtful side-glasses. He had an odd autobiographical habit which led him to compose in his mind from time to time a short sentence about himself containing a subject in the third person and a predicate in the past tense. He never gave alms to beggars and walked firmly, carrying a stout hazel.

He had been for many years cashier of a private bank in Baggot Street. Every morning he came in from Chapelizod by tram. At midday he went to Dan Burke’s and took his lunch, a bottle of lager beer and a small trayful of arrowroot biscuits. At four o’clock he was set free. He dined in an eating-house in George’s Street where he felt himself safe from the society of Dublin’s gilded youth and where there was a certain plain honesty in the bill of fare. His evenings were spent either before his landlady’s piano or roaming about the outskirts of the city. His liking for Mozart’s music brought him sometimes to an opera or a concert: these were the only dissipations of his life.

He had neither companions nor friends, church nor creed. He lived his spiritual life without any communion with others, visiting his relatives at Christmas and escorting them to the cemetery when they died. He performed these two social duties for old dignity’s sake but conceded nothing further to the conventions which regulate the civic life. He allowed himself to think that in certain circumstances he would rob his hank but, as these circumstances never arose, his life rolled out evenly, an adventureless tale.

One evening he found himself sitting beside two ladies in the Rotunda. The house, thinly peopled and silent, gave distressing prophecy of failure. The lady who sat next him looked round at the deserted house once or twice and then said:

“What a pity there is such a poor house tonight! It’s so hard on people to have to sing to empty benches.”

He took the remark as an invitation to talk. He was surprised that she seemed so little awkward. While they talked he tried to fix her permanently in his memory. When he learned that the young girl beside her was her daughter he judged her to be a year or so younger than himself. Her face, which must have been handsome, had remained intelligent. It was an oval face with strongly marked features. The eyes were very dark blue and steady. Their gaze began with a defiant note but was confused by what seemed a deliberate swoon of the pupil into the iris, revealing for an instant a temperament of great sensibility. The pupil reasserted itself quickly, this half-disclosed nature fell again under the reign of prudence, and her astrakhan jacket, moulding a bosom of a certain fullness, struck the note of defiance more definitely.

He met her again a few weeks afterwards at a concert in Earlsfort Terrace and seized the moments when her daughter’s attention was diverted to become intimate. She alluded once or twice to her husband but her tone was not such as to make the allusion a warning. Her name was Mrs. Sinico. Her husband’s great-great-grandfather had come from Leghorn. Her husband was captain of a mercantile boat plying between Dublin and Holland; and they had one child.

Meeting her a third time by accident he found courage to make an appointment. She came. This was the first of many meetings; they met always in the evening and chose the most quiet quarters for their walks together. Mr. Duffy, however, had a distaste for underhand ways and, finding that they were compelled to meet stealthily, he forced her to ask him to her house. Captain Sinico encouraged his visits, thinking that his daughter’s hand was in question. He had dismissed his wife so sincerely from his gallery of pleasures that he did not suspect that anyone else would take an interest in her. As the husband was often away and the daughter out giving music lessons Mr. Duffy had many opportunities of enjoying the lady’s society. Neither he nor she had had any such adventure before and neither was conscious of any incongruity. Little by little he entangled his thoughts with hers. He lent her books, provided her with ideas, shared his intellectual life with her. She listened to all.

Sometimes in return for his theories she gave out some fact of her own life. With almost maternal solicitude she urged him to let his nature open to the full: she became his confessor. He told her that for some time he had assisted at the meetings of an Irish Socialist Party where he had felt himself a unique figure amidst a score of sober workmen in a garret lit by an inefficient oil-lamp. When the party had divided into three sections, each under its own leader and in its own garret, he had discontinued his attendances. The workmen’s discussions, he said, were too timorous; the interest they took in the question of wages was inordinate. He felt that they were hard-featured realists and that they resented an exactitude which was the produce of a leisure not within their reach. No social revolution, he told her, would be likely to strike Dublin for some centuries.

She asked him why did he not write out his thoughts. For what, he asked her, with careful scorn. To compete with phrasemongers, incapable of thinking consecutively for sixty seconds? To submit himself to the criticisms of an obtuse middle class which entrusted its morality to policemen and its fine arts to impresarios?

He went often to her little cottage outside Dublin; often they spent their evenings alone. Little by little, as their thoughts entangled, they spoke of subjects less remote. Her companionship was like a warm soil about an exotic. Many times she allowed the dark to fall upon them, refraining from lighting the lamp. The dark discreet room, their isolation, the music that still vibrated in their ears united them. This union exalted him, wore away the rough edges of his character, emotionalised his mental life. Sometimes he caught himself listening to the sound of his own voice. He thought that in her eyes he would ascend to an angelical stature; and, as he attached the fervent nature of his companion more and more closely to him, he heard the strange impersonal voice which he recognised as his own, insisting on the soul’s incurable loneliness. We cannot give ourselves, it said: we are our own. The end of these discourses was that one night during which she had shown every sign of unusual excitement, Mrs. Sinico caught up his hand passionately and pressed it to her cheek.

Mr. Duffy was very much surprised. Her interpretation of his words disillusioned him. He did not visit her for a week, then he wrote to her asking her to meet him. As he did not wish their last interview to be troubled by the influence of their ruined confessional they meet in a little cakeshop near the Parkgate. It was cold autumn weather but in spite of the cold they wandered up and down the roads of the Park for nearly three hours. They agreed to break off their intercourse: every bond, he said, is a bond to sorrow. When they came out of the Park they walked in silence towards the tram; but here she began to tremble so violently that, fearing another collapse on her part, he bade her good-bye quickly and left her. A few days later he received a parcel containing his books and music.

Four years passed. Mr. Duffy returned to his even way of life. His room still bore witness of the orderliness of his mind. Some new pieces of music encumbered the music-stand in the lower room and on his shelves stood two volumes by Nietzsche: Thus Spake Zarathustra and The Gay Science. He wrote seldom in the sheaf of papers which lay in his desk. One of his sentences, written two months after his last interview with Mrs. Sinico, read: Love between man and man is impossible because there must not be sexual intercourse and friendship between man and woman is impossible because there must be sexual intercourse. He kept away from concerts lest he should meet her. His father died; the junior partner of the bank retired. And still every morning he went into the city by tram and every evening walked home from the city after having dined moderately in George’s Street and read the evening paper for dessert.

One evening as he was about to put a morsel of corned beef and cabbage into his mouth his hand stopped. His eyes fixed themselves on a paragraph in the evening paper which he had propped against the water-carafe. He replaced the morsel of food on his plate and read the paragraph attentively. Then he drank a glass of water, pushed his plate to one side, doubled the paper down before him between his elbows and read the paragraph over and over again. The cabbage began to deposit a cold white grease on his plate. The girl came over to him to ask was his dinner not properly cooked. He said it was very good and ate a few mouthfuls of it with difficulty. Then he paid his bill and went out.

He walked along quickly through the November twilight, his stout hazel stick striking the ground regularly, the fringe of the buff Mail peeping out of a side-pocket of his tight reefer overcoat. On the lonely road which leads from the Parkgate to Chapelizod he slackened his pace. His stick struck the ground less emphatically and his breath, issuing irregularly, almost with a sighing sound, condensed in the wintry air. When he reached his house he went up at once to his bedroom and, taking the paper from his pocket, read the paragraph again by the failing light of the window. He read it not aloud, but moving his lips as a priest does when he reads the prayers Secreto. This was the paragraph:

DEATH OF A LADY AT SYDNEY PARADE

A PAINFUL CASE

Today at the City of Dublin Hospital the Deputy Coroner (in the absence of Mr. Leverett) held an inquest on the body of Mrs. Emily Sinico, aged forty-three years, who was killed at Sydney Parade Station yesterday evening. The evidence showed that the deceased lady, while attempting to cross the line, was knocked down by the engine of the ten o’clock slow train from Kingstown, thereby sustaining injuries of the head and right side which led to her death.

James Lennon, driver of the engine, stated that he had been in the employment of the railway company for fifteen years. On hearing the guard’s whistle he set the train in motion and a second or two afterwards brought it to rest in response to loud cries. The train was going slowly.

P. Dunne, railway porter, stated that as the train was about to start he observed a woman attempting to cross the lines. He ran towards her and shouted, but, before he could reach her, she was caught by the buffer of the engine and fell to the ground.

A juror. “You saw the lady fall?”

Witness. “Yes.”

Police Sergeant Croly deposed that when he arrived he found the deceased lying on the platform apparently dead. He had the body taken to the waiting-room pending the arrival of the ambulance.

Constable 57 corroborated.

Dr. Halpin, assistant house surgeon of the City of Dublin Hospital, stated that the deceased had two lower ribs fractured and had sustained severe contusions of the right shoulder. The right side of the head had been injured in the fall. The injuries were not sufficient to have caused death in a normal person. Death, in his opinion, had been probably due to shock and sudden failure of the heart’s action.

Mr. H. B. Patterson Finlay, on behalf of the railway company, expressed his deep regret at the accident. The company had always taken every precaution to prevent people crossing the lines except by the bridges, both by placing notices in every station and by the use of patent spring gates at level crossings. The deceased had been in the habit of crossing the lines late at night from platform to platform and, in view of certain other circumstances of the case, he did not think the railway officials were to blame.

Captain Sinico, of Leoville, Sydney Parade, husband of the deceased, also gave evidence. He stated that the deceased was his wife. He was not in Dublin at the time of the accident as he had arrived only that morning from Rotterdam. They had been married for twenty-two years and had lived happily until about two years ago when his wife began to be rather intemperate in her habits.

Miss Mary Sinico said that of late her mother had been in the habit of going out at night to buy spirits. She, witness, had often tried to reason with her mother and had induced her to join a League. She was not at home until an hour after the accident. The jury returned a verdict in accordance with the medical evidence and exonerated Lennon from all blame.

The Deputy Coroner said it was a most painful case, and expressed great sympathy with Captain Sinico and his daughter. He urged on the railway company to take strong measures to prevent the possibility of similar accidents in the future. No blame attached to anyone.

Mr. Duffy raised his eyes from the paper and gazed out of his window on the cheerless evening landscape. The river lay quiet beside the empty distillery and from time to time a light appeared in some house on the Lucan road. What an end! The whole narrative of her death revolted him and it revolted him to think that he had ever spoken to her of what he held sacred. The threadbare phrases, the inane expressions of sympathy, the cautious words of a reporter won over to conceal the details of a commonplace vulgar death attacked his stomach. Not merely had she degraded herself; she had degraded him. He saw the squalid tract of her vice, miserable and malodorous. His soul’s companion! He thought of the hobbling wretches whom he had seen carrying cans and bottles to be filled by the barman. Just God, what an end! Evidently she had been unfit to live, without any strength of purpose, an easy prey to habits, one of the wrecks on which civilisation has been reared. But that she could have sunk so low! Was it possible he had deceived himself so utterly about her? He remembered her outburst of that night and interpreted it in a harsher sense than he had ever done. He had no difficulty now in approving of the course he had taken.

As the light failed and his memory began to wander he thought her hand touched his. The shock which had first attacked his stomach was now attacking his nerves. He put on his overcoat and hat quickly and went out. The cold air met him on the threshold; it crept into the sleeves of his coat. When he came to the public-house at Chapelizod Bridge he went in and ordered a hot punch.

The proprietor served him obsequiously but did not venture to talk. There were five or six workingmen in the shop discussing the value of a gentleman’s estate in County Kildare They drank at intervals from their huge pint tumblers and smoked, spitting often on the floor and sometimes dragging the sawdust over their spits with their heavy boots. Mr. Duffy sat on his stool and gazed at them, without seeing or hearing them. After a while they went out and he called for another punch. He sat a long time over it. The shop was very quiet. The proprietor sprawled on the counter reading the Herald and yawning. Now and again a tram was heard swishing along the lonely road outside.

As he sat there, living over his life with her and evoking alternately the two images in which he now conceived her, he realised that she was dead, that she had ceased to exist, that she had become a memory. He began to feel ill at ease. He asked himself what else could he have done. He could not have carried on a comedy of deception with her; he could not have lived with her openly. He had done what seemed to him best. How was he to blame? Now that she was gone he understood how lonely her life must have been, sitting night after night alone in that room. His life would be lonely too until he, too, died, ceased to exist, became a memory, if anyone remembered him.

It was after nine o’clock when he left the shop. The night was cold and gloomy. He entered the Park by the first gate and walked along under the gaunt trees. He walked through the bleak alleys where they had walked four years before. She seemed to be near him in the darkness. At moments he seemed to feel her voice touch his ear, her hand touch his. He stood still to listen. Why had he withheld life from her? Why had he sentenced her to death? He felt his moral nature falling to pieces.

When he gained the crest of the Magazine Hill he halted and looked along the river towards Dublin, the lights of which burned redly and hospitably in the cold night. He looked down the slope and, at the base, in the shadow of the wall of the Park, he saw some human figures lying. Those venal and furtive loves filled him with despair. He gnawed the rectitude of his life; he felt that he had been outcast from life’s feast. One human being had seemed to love him and he had denied her life and happiness: he had sentenced her to ignominy, a death of shame. He knew that the prostrate creatures down by the wall were watching him and wished him gone. No one wanted him; he was outcast from life’s feast. He turned his eyes to the grey gleaming river, winding along towards Dublin. Beyond the river he saw a goods train winding out of Kingsbridge Station, like a worm with a fiery head winding through the darkness, obstinately and laboriously. It passed slowly out of sight; but still he heard in his ears the laborious drone of the engine reiterating the syllables of her name.

He turned back the way he had come, the rhythm of the engine pounding in his ears. He began to doubt the reality of what memory told him. He halted under a tree and allowed the rhythm to die away. He could not feel her near him in the darkness nor her voice touch his ear. He waited for some minutes listening. He could hear nothing: the night was perfectly silent. He listened again: perfectly silent. He felt that he was alone.

James Joyce: A Painful Case

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive I-J, Joyce, James, Joyce, James

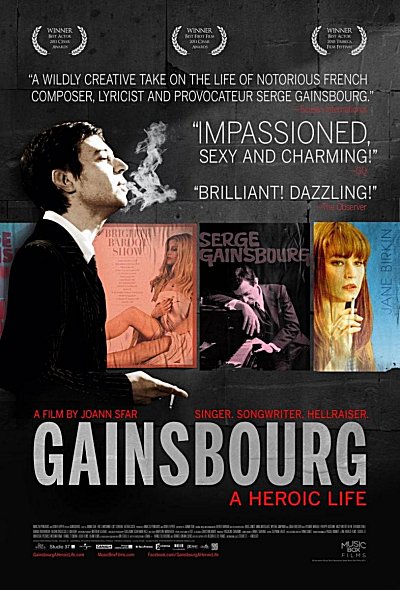

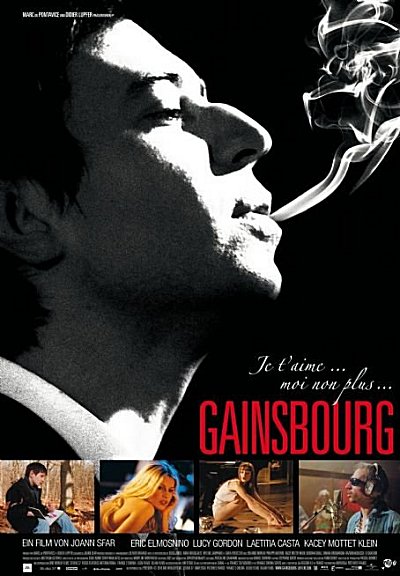

Serge Gainsbourg, vie héroïque

film met Lucy Gordon

CANVAS TV BE

vrijdag 15 februari 2013 – 22.10

Film, Frankrijk – 2010

Duur: 130 min

Door haar Joods-Russische afkomst heeft de familie van de jonge Lucien Ginsburg het niet gemakkelijk in het bezette Parijs tijdens de oorlogsjaren. Later gaat Lucien aan de kunstschool studeren. Hij komt aan de kost met optredens in bars en cabarets. In de jaren 60 breekt hij door als Serge Gainsbourg, de ster van het cabaret de Swinging Sixties. Hij verlegt de grenzen van het chanson en maakt naam met zijn onconventionele muziek en zijn rebelse gedrag. Hij is bevriend met onder meer Brigitte Bardot en Juliette Gréco. Gainsbourg wordt een icoon van de Franse cultuur, maar maakt ook ophef met zijn turbulente liefdesleven met Jane Birkin en vele anderen

Regisseur Joann SFAR

Acteurs

Eric ELMOSNINO / Serge Gainsbourg

Lucy GORDON / Jane Birkin

Laetitia CASTA / Brigitte Bardot

Anna MOUGLALIS / Juliette Gréco

Sara FORESTIER / France Gall

Kacey MOTTET KLEIN / Lucien Ginsburg

Lucy Gordon

(May 22, 1980 – May 20, 2009)

Lucy Gordon was a British actress and model, born in Oxford, England. She committed suicide on 20 May 2009, in her apartment in Paris, France, two days before her 29th birthday.

Filmography

2001: Perfume (Lucy Gordon as Sarah)

2001: Serendipity (Lucy Gordon as Caroline Mitchell)

2002: The Four Feathers by Shekhar Kapur (Lucy Gordon as Isabelle)

2005: The Russian Dolls by Cédric Klapisch (Lucy Gordon as Celia Shelburn)

2007: Serial de Kevin Arbouet et Larry Strong (Lucy Gordon as Sadie Grady)

2007: Spider-Man 3 by Sam Raimi (Lucy Gordon as Jennifer Dugan)

2008: Frost by Steve Clark (Lucy Gordon as Kate Hardwick)

2009: Brief Interviews with Hideous Men by John Krasinski (Lucy Gordon as Hitchhiker)

2009: Cinéman (Lucy gordon as Fernandel’s friend)

2010: Serge Gainsbourg, vie héroïque (Lucy Gordon as Jane Birkin)

To be published soon Collected Stories by Jef van Kempen:

(with Angel of Paris. Life and death of Lucy Gordon)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: AUDIO, CINEMA, RADIO & TV, Jef van Kempen, Kempen, Jef van, Lucy Gordon

Albertine Kehrer

(1826-1852)

Wat niet is uit te staan

Wat niet is uit te staan

De geur van ingemaakte kropsla

Rijmend proza; slappe thee;

Vorken met een haringsmaakje

Op een uitgezocht diner;

Een bon mot, dat, niet begrepen,

Uitleg of herhaling eist;

Van uw goed te zijn verstoken,

Als gij voor genoegen reist;

In de kerk, in januari,

Bij abuis uw stoof niet warm;

Als gij worsten denkt te stoppen,

Heel veel gaten in de darm

(…)

En – een hand, die niet gedrukt wordt,

Zoo trouwhartig als gij ‘t doet;

(…)

Door de Torenstraat te moeten

Met een parapluie als ‘t stormt;

(…)

Complimenten aan te horen,

Niet verdiend en niet gemeend;

En – een vingerhoed met gaatjes

Dien gij van een kennis leent;

‘t Carillon des maandagsochtends,

Vrijdagmorgens bovendien,

Ingesteld in oude dagen,

Tot vermaak van ‘k weet niet wien;

Naaiwerk, thuis gestuurd, doortrokken

Met een geur van zoutevis

Was opdoen met winterhanden

Als het goed bevroren is;

Rolpens in ‘t begin van juli

Onuitsprekelijk zout en hard:

Iemand met een neusverkoudheid

Naast u zittend op ‘t concert

Zonneschijn en zomerwarmte

Als gij op een stoomboot wacht;

En in ‘t eind de lof der zotten

Openlijk u toegebracht!

Albertine Kehrer poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Albertine Kehrer, Archive K-L, Kehrer, Albertine

Gottfried Keller

(1819–1890)

Modernster Faust

Ich bin ein ganzer Held! Den Mantel umgeschlagen

– Romantisch schwarzer Samt erglänzt an Kleid und Kragen –

Stürm ich dahin in eitlem Wahn!

Ob Samt? ob nur Kattun? es war ein langes Zanken

Mit meinem Mütterlein; doch fest und ohne Wanken

Erstritt ich Samt, und niemand sieht mir’s an.

Leichtsinnig, hohen Muts mach ich die Morgenrunde;

Die Wintersonne scheint, Cigarro brennt im Munde,

Den ich dem Kaufmann schuldig bin;

Die Wintersonne scheint, kalt ist ihr Silberflimmer,

Und kalt ist mir das Herz, kalt meiner Augen Schimmer

Und trüb, befangen immerhin.

Da treff ich einen Freund auf meiner irren Bahn,

Wir halten mit Geklatsch ein halbes Stündchen an;

Wie wenn zwei alte Hexen schelten,

So bricht von Bosheit nun und Neid ein ganzer Chor

Von Zoten, schlechtem Witz und Haß aus uns hervor,

Daß mir verschämt die eignen Ohren gellten.

Da kommt ein Handwerksbursch, bleich, mit zerrißnen Sohlen,

Mütz in der Hand, geduckt, ein Gäblein sich zu holen;

Mit einem Kreuzer wär ihm wohlgetan.

Doch weil ich diesen nicht in leerer Tasche trage

Und doch nicht freundlich ihm es zu gestehen wage,

Fahr ich ihn rauh abweisend an.

Ob mir das kühle Herz in rascher Scham erglüht,

Ob auch ein blut’ger Schnitt mir durch die Seele zieht:

Man sieht es nicht in meinen Blicken;

Ich habe ja gelernt, mit höhnisch leichtem Spiel

Den halberfrornen Lenz, das innere Gefühl,

Wenn es erblühen will, zu unterdrücken!

O ich war treu, wie Gold, begeistert, klar und offen;

Ein Blatt ums andre fiel von meinem grünen Hoffen,

Und taube Nüsse tauscht ich ein!

Schmach über dich, o Welt! du hast mich ganz beladen

Mit deinem Schlamm und Staub! O könnt ich rein mich baden

Im wilden Meer, sollt’s auch ein Sterben sein!

Kokett ist dies Gedicht, Naivetät erlogen

Und nur das Schnöde wahr! Ich hab euch arg betrogen,

Denn zwei geworden sind mir Herz und Mund!

Ich bin ganz euer Bild: selbstsüchtig, falsch und eitel

Und unklar in mir selbst; vom Fuße bis zur Scheitel

Ein europäisch schlechter Hund!

Gottfried Keller poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive K-L, Keller, Gottfried

Karl Kraus

(1874-1936)

Die Freiheit, die ich nicht meine

Die Freiheit, die möcht’ ich echt haben,

drum möcht’ ich sie früher befrein

von solchen, die zwar recht haben,

doch ohne berechtigt zu sein.

Denn die, deren die sich erfrecht haben,

ist die Freiheit nicht, die ich mein’!

1925

Karl Kraus poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive K-L, Kraus, Karl

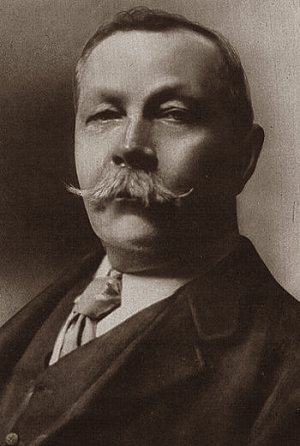

Arthur Conan Doyle

(1859-1930)

The Bigot

The foolish Roan fondly thought

That gods must be the same to all,

Each alien idol might be brought

Within their broad Pantheon Hall.

The vision of a jealous Jove

Was far above their feeble ken;

They had no Lord who gave them love,

But scowled upon all other men.

But in our dispensation bright,

What noble progress have we made!

We know that we are in the light,

And outer races in the shade.

Our kindly creed ensures us this–

That Turk and infidel and Jew

Are safely banished from the bliss

That’s guaranteed to me and you.

The Roman mother understood

That, if the babe upon her breast

Untimely died, the gods were good,

And the child’s welfare manifest.

With tender guides the soul would go

And there, in some Elysian bower,

The tiny bud plucked here below

Would ripen to the perfect flower.

Poor simpleton! Our faith makes plain

That, if no blest baptismal word

Has cleared the babe, it bears the stain

Which faithless Adam had incurred.

How philosophical an aim!

How wise and well-conceived a plan

Which holds the new-born babe to blame

For all the sins of early man!

Nay, speak not of its tender grace,

But hearken to our dogma wise:

Guilt lies behind that dimpled face,

And sin looks out from gentle eyes.

Quick, quick, the water and the bowl!

Quick with the words that lift the load!

Oh, hasten, ere that tiny soul

Shall pay the debt old Adam owed!

The Roman thought the souls that erred

Would linger in some nether gloom,

But somewhere, sometime, would be spared

To find some peace beyond the tomb.

In those dark halls, enshadowed, vast,

They flitted ever, sad and thin,

Mourning the unforgotten past

Until they shed the taint of sin.

And Pluto brooded over all

Within that land of night and fear,

Enthroned in some dark Judgment Hall,

A god himself, reserved, austere.

How thin and colourless and tame!

Compare our nobler scheme with it,

The howling souls, the leaping flame,

And all the tortures of the pit!

Foolish half-hearted Roman hell!

To us is left the higher thought

Of that eternal torture cell

Whereto the sinner shall be brought.

Out with the thought that God could share

Our weak relenting pity sense,

Or ever condescend to spare

The wretch who gave Him just offence!

‘Tis just ten thousand years ago

Since the vile sinner left his clay,

And yet no pity can he know,

For as he lies in hell to-day

So when ten thousand years have run

Still shall he lie in endless night.

O God of Love! O Holy One!

Have we not read Thy ways aright?

The godly man in heaven shall dwell,

And live in joy before the throne,

Though somewhere down in nether hell

His wife or children writhe and groan.

From his bright Empyrean height

He sees the reek from that abyss–

What Pagan ever dreamed a sight

So holy and sublime as this!

Poor foolish folk! Had they begun

To weigh the myths that they professed,

One hour of reason and each one

Would surely stand a fraud confessed.

Pretending to believe each deed

Of Theseus or of Hercules,

With fairy tales of Ganymede,

And gods of rocks and gods of trees!

No, no, had they our purer light

They would have learned some saner tale

Of Balaam’s ass, or Samson’s might,

Or prophet Jonah and his whale,

Of talking serpents and their ways,

Through which our foolish parents strayed,

And how there passed three nights and days

Before the sun or moon was made!

· · · ·

O Bigotry, you crowning sin!

All evil that a man can do

Has earthly bounds, nor can begin

To match the mischief done by you–

You, who would force the source of love

To play your small sectarian part,

And mould the mercy from above

To fit your own contracted heart.

Arthur Conan Doyle poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive C-D, Arthur Conan Doyle, Doyle, Arthur Conan

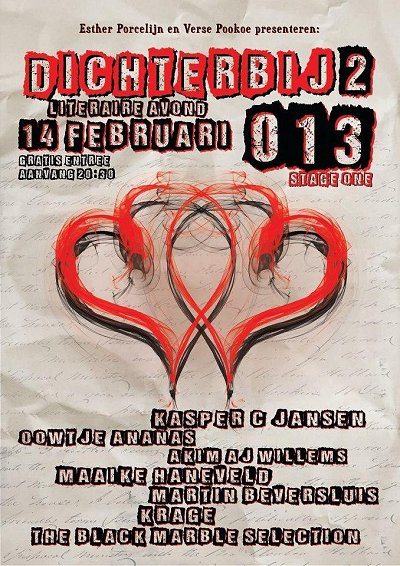

Esther Porcelijn en Verse Pookoe presenteren: Dichterbij #2 + Kasper C Jansen + Oowtje Ananas + Akim AJ Willems + Maaike Haneveld + Martin Beversluis + Krage + The Black Marble Selection

do 14 feb 13

Poppodium 013 Tilburg

Tijdens deze valentijnsavond organiseren stadsdichter Esther Porcelijn en Verse Pookoe de tweede editie van een nieuwe maandelijkse literaire avond genaamd: ‘Dichterbij’. De eerste editie vond plaats in de Rode Salon van De NWE Vorst. De avond zal een combinatie zijn van proza, poëzie en muziek met dichters en andere woordkunstenaars uit Tilburg en de rest van het land. Zowel beginnend talent als ervaren schrijvers krijgen de kans om het podium te betreden.

Na de sluiting van Ruimte-X (Ernest Potters) en het stoppen van Aardige Jongens (Martijn Neggers), voelde Esther Porcelijn en Verse Pookoe zich geroepen om de literaire wereld van Tilburg in beweging te houden en ook een nieuw publiek aan te spreken met deze nieuwe avonden. Verse Pookoe en Esther Porcelijn nodigen u uit om gezellig langs te komen op deze gratis avond.

Locatie: Stage01 – Poppodium 013 Tilburg

Zaal open: 19:30 uur

Aanvang: 20:00 uur

Tickets: Gratis

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Porcelijn, Esther, Porcelijn, Esther

Mireille Havet

(1898-1932)

Histoire du petit cheval noir

Le petit cheval, noir comme du jais, trotte sur la route de campagne. Ses deux oreilles bien levées comme des cornets à surprise et sa queue empanachée comme un plumeau qu’agite la brise.

Il est content, le petit cheval, parce que l’air est bleu sur toute la campagne. La carriole qui sonne derrière sa croupe luisante est légère et le paysan Mathieu gai et propre dans sa blouse bleue, n’emporte jamais de fouet.

« Ah les beaux cailloux ! comme ils roulent bien sous mes quatre sabots, pense le petit cheval, et que mon estomac est agréablement rempli d’avoine. Allons, vite, vite à la ferme qui est située dans la vallée. Là, je retrouverai un petit cheval blanc que j’affectionne énormément. »

Mais voilà, que sous le lourd soleil de midi, qui est monté au fond du ciel, le gai paysan Mathieu s’est endormi. Sa bonne grosse tête est secouée de droite à gauche, de gauche à droite, par les cahots de la voiture et, devant ses yeux clos, passent des visions champêtres… La route, avant d’arriver à la ferme est raide, si raide, qu’on n’y pourrait jouer à courir sans tomber.

Mais, le petit cheval ne sait pas cela, parce qu’une main sûre, jusqu’à ce matin-là, avait toujours tenu ses guides. Et de toute la force de ses quatre jambes solides il se lance dans le sentier, avec par derrière lui, la carriole sonnante. Ah ! qu’est-il arrivé ?

Mathieu fut réveillé par une grande secousse, qui le projeta en l’air, comme une balle, et par un hennissement pitoyable. Le petit cheval noir, plié sur ses genoux de devant, était recouvert, à moitié, par la carriole qui pesait sur son dos… et il hennissait… il hennissait, parce qu’il avait mal à ses genoux écorchés.

« Ah ! pensait le petit cheval, comment faire maintenant ? j’ai si mal ! et je n’ai pas la force de me relever. J’étais si heureux de courir, avec du soleil de tous les côtés et l’air piquant dans mes naseaux ouverts. Maintenant je vais boiter comme un vieux cheval infirme. Quelle tristesse ! » Et il pleurait.

Ce n’est qu’une heure après, que Mathieu avec, d’autres garçons, purent dégager le petit cheval noir et l’aider à se relever.

Mais dans quel état ! Toute la peau de ses genoux enlevée. Ses pauvres genoux ! On le ramena à son écurie : là-haut, sur le coteau, pendant que le soleil se couchait, comme cela, avec une multitude de rayons. Le ciel ressemblait à un champ de blé.

Et le petit cheval sentait son cœur lourd comme une grosse pierre et il se disait : « Vais-je mourir ? » Mais il ne mourut pas. Ce n’était que des écorchures. On le soigna très bien. On le fit reposer et on lui donna abondamment à manger.

Cependant depuis, il n’a jamais voulu, mais jamais ! reprendre le chemin en pente qui conduit dans la vallée.

La Maison dans l’œil du chat. Paris, éditions Georges Crès & Cie, 1917

Mireille Havet poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive G-H, Havet, Mireille, Mireille Havet

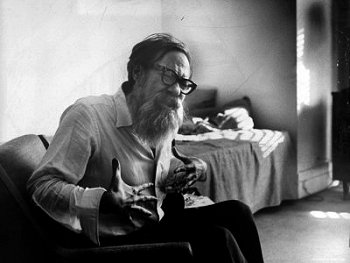

John Berryman

(1914-1972)

Dream Song 4

Filling her compact & delicious body

with chicken paprika, she glanced at me

twice.

Fainting with interest, I hungered back

and only the fact that her husband & four other people

kept me from springing on her

or falling at her little feet and crying

“You are the hottest one for years of night

Henry’s dazed eyes

have enjoyed, Brilliance.” I advanced upon

(despairing) my spumoni. — Sir Bones: is stuffed,

de world, wif feeding girls. —

Black hair, complexion Latin, jewelled eyes

downcast . . . The slob beside her feasts . . . What wonders is

she sitting on, over there?

The restaurant buzzes. She might as well be on Mars.

Where did it all go wrong? There ought to be a law against Henry.

–Mr. Bones: there is.

John Berryman poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive A-B

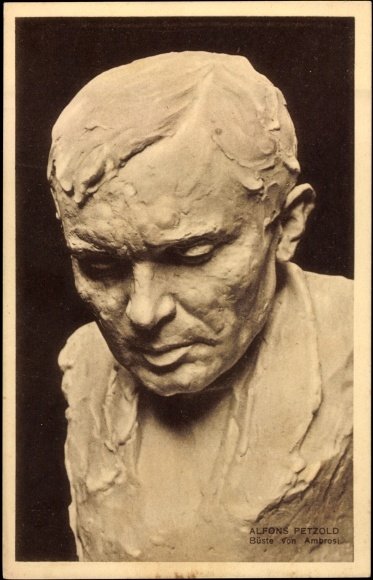

Alfons Petzold

(1882-1923)

Abendlied im Kriege

Nun ist der Tag vergangen,

Der Sonne goldnes Rot

Verblaßt auf ihren Wangen,

Als läge sie im Tod.

Der Abend von der Herde

Der Sterne eingekreist,

Beschenkt die weite Erde

Mit seinem frommen Geist.

Die ist so arm geworden

Und trägt so böse Qual,

Seitdem das grause Morden

Braust über Berg und Tal.

Nur Scham kann ihr noch geben

Des Tages blanker Schein,

Drum hüllt sie gern ihr Leben

In weiches Dunkel ein.

Wohl geht auch jetzt das Grausen

Herum im Dorf und Stadt:

Es liegt so mancher draußen,

Der keinen Schlaf mehr hat. –

Und viele Frauen lauschen,

Indes die Lampe singt,

Ob nicht ein Mantelrauschen

Den Fernen näher bringt. –

Doch der steht mit den andern,

Verderben in der Faust,

Sieht tausend Sterne wandern

Granatensturmumbraust

Und nicht den Abend kommen

Mit seinem stillen Geist,

Der allen wahrhaft Frommen

Den Weg des Friedens weist.

Alfons Petzold poetry

Aus der Sammlung Der stählerne Schrei

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive O-P, Petzold, Alfons

Vlezige mensen, wethouders, poppetjes, kastjes

Welkom iedereen! Het thema van vanavond is: ‘Verlichting’.

De stroming in de 17e en 18e eeuw die ons tot het inzicht heeft laten komen dat de Rede het enige instrument is om tot Waarheid te komen. Weg met het bijgeloof, weg met de onderdrukking van de kerk, weg met het feodale systeem, en op naar grondrechten, gelijkheid en vrijheid waarvoor vervolgens gestreden werd in de Franse Revolutie. Dit alles is uiteraard veroorzaakt door historici, filosofen en ontevreden burgers, maar niet enkel door hen. De Pamflettisten hebben zich een slag in de rondte gewerkt om iedereen te laten weten hoe vreselijk de adel was en dat de koning elke dag baadde in kinderbloed. Zij wisten met opruiende teksten, beschuldigingen, beledigingen en verdachtmakingen de burgerij voor zich te winnen. Ongeacht of de boodschap waarheid bevatte of niet.

Herkenbaar?

Wellicht dat we de pamflettisten van nu vanavond op het podium zullen zien.

Dan zullen we hen vast horen over wethouders van vroeger en van nu, en over andere mensen uit de politiek. Over hoe een of andere handeling van een of ander iemand exemplarisch is voor dit ‘dorp’ en haar mentaliteit.

Het kan ook zijn dat iemand in deze zaal hard wordt aangepakt. Maar niet té hard, het moet natuurlijk wel gezellig en grappig blijven. Maar om het grappig te laten zijn, moet het wel gaan over iemand die wij allemaal (persoonlijk) kennen, anders valt er niets te lachen. Als je dan niet lacht ben je de gebeten hond en dus iemand zonder humor.

Harde uitspraken moeten grappig zijn, anders zijn ze alleen maar pijnlijk! Jongens, lach dan, lach dan!

Het lijkt wel een formule. Een pamfletformule!

Eens kijken, wat zou de formule deze avond kunnen bevatten?

Ik gok dat het woord ‘dorp’ toch wel een aantal keer valt.

Wethouder van Cultuur Marjo Frenk is een goede kansmaker op een naamsvermelding denk ik.

Anton Dautzenberg komt vast weer met een sexuele verdachtmaking van iemand, misschien voormalig stadsdichter Cees van Raak die seks heeft gehad met de hond van Daan Taks? (Nachtdichter van Tilburg.) Wellicht betrekt hij er een landelijke bekendheid in, want dat onderscheid moet uiteraard gemaakt worden! Het onderscheid tussen de landelijke bekendheid versus het provincialisme dat noodzakelijk in die zin betrokken is als je een accent legt op lándelijke bekendheid. Hij wel, verdomme. Dan maar een grapje maken: Poep! Ha. Ha. Ha. Enig!

Misschien houdt Anton (zo mag ik ‘m noemen, zegt ook weer wat over mij, ik ken hem. Dat maakt mij iets meer immuun voor zijn harde uitspraken die mij mogelijk te wachten staan. Wauw!) eerder een betoog over iets met bloed en de nachtburgemeester Godelieve Engbersen. Iets over een moord die gepleegd is waarbij wederom de hond van Daan Taks betrokken was.

Luuk Koelman zal hoe dan ook de woede van heel het land op de hals halen met zijn column, dat moet haast wel. Als je de woede van bijna heel het land al op de hals hebt gehaald, met de column over Mariska Orbán-de Haas, dan moet je toch minstens het hele land boos maken wil je nog opvallen. Maar wij in de zaal zijn ‘insiders on the joke’ dus wij kunnen dan met een gerust hart zeggen dat de rest van het land zo kleinburgerlijk is en nooit iets snapt. “Hoe kun je die ironie nou niet inzien? On-be-grijpelijk”, fluistert ene Lidy uit Tilburg dan tegen haar man Hans; “Wij zijn dan nog behoorlijk open-minded, toch Hans?” “Gelukkig maar.”

Wat maakt het toch zo smakelijk, dat pakken op de persoon, de Ad Hominem?

“Polemiek!” Hoor ik Antonnetje en zijn billemaat Erik Hannema roepen in mijn hoofd.

Ja, polemiek jongens, polemiek! Het is een kunst, dat moet gezegd, maar bedrijf het dan ook! Polemiek betekent redetwisten. Daar hebben we het woord ‘rede’ dus weer. Diezelfde rede die ons tot de waarheid zou kunnen brengen. De twee deelnemers zouden het komen tot waarheid hoog in het vaandel hebben staan, waarom zou je anders redetwisten? Om je gelijk te halen misschien? Zou kunnen, maar een gelijk zonder daadwerkelijk gelijk lijkt mij weinig voldoenend. Misschien wordt deze kunst wel veel bedreven op avonden zoals deze uit een gevoel van nostalgie: “Vroeger kon men dit nog, vroeger was er nog iets om voor te strijden, vroeger waren er nog revoluties in het Westen!” Onrust stoken om mensen op te ruien en te motiveren. Maar, waarom zou je dan mensen persoonlijk pakken met fictieve gebeurtenissen of –verdachtmakingen?

Misschien omdat het te lang bespreken van de ware gebeurtenissen, fouten en terechte verdachtmakingen te pijnlijk en ongemakkelijk is. Het moet wel gezellig blijven en dus worden er een paar fictieve gebeurtenissen tussen de regels geplakt zodat de mogelijkheid dat de ware gebeurtenissen ook fictief zijn nog blijft bestaan.

We willen wel de roddels maar niet de confrontatie, niet echt. We willen alleen de smakelijke sappige details mits ze weinig lijken te zeggen over onszelf. Is ook makkelijker natuurlijk! De ander is gek, de ander is grappig.

Is het waar dat men vroeger dan wel eindeloos opzoek was naar de waarheid? Ik denk het niet, althans, niet meer dan nu. Ten tijde van de Franse Revolutie verzon de lage adel er ook op los, wat er maar nodig was om de burgers aan hun kant te krijgen. Dat dit lukte en uiteindelijk meer vrijheid tot stand bracht is een feit. Al waren de donkere tijden van de middeleeuwen iets minder donker dan zij ons tot op de dag van vandaag hebben doen denken. Maar zij deden dit met gevaar voor eigen leven, niet braaf in een zaal in Tilburg. Waarom zouden wij dan een hang hebben naar die revoluties van vroeger en de pamflettaal die daarmee samenhangt? Welke donkere tijden proberen wij te ontvluchten?

Kijk, Jace vd Ven (eerste stadsdichter van Tilburg) komt uit vroeger, dus hij hoeft het vroeger niet naar nu te trekken. Hij weet al hoe het toen was en kan hoogstens oprecht nostalgische gevoelens ervaren. Juist doordat hij uit vroeger komt weet hij ook dat de geschiedenis zich herhaalt. Hij kan zijn nootjes pakken, naar de show kijken en pogen iets universeels te schrijven als dichter. Want dat kan hij. Jace kan, en misschien wel hierdoor, gedichten maken die buiten de tijd staan. Dat is wat een goed gedicht doet.

Misschien dat Tom America ons nog een vieze film toont, met in een soundscape de naam van Burgermeester Noordanus in herhaling. Of iets met een jong Thais meisje, gespeeld door mij, dan kunnen we dat meteen voor het TilT-festival gebruiken, Tom! Theatermaker Peer de Graaf en dichter Martin Beversluis doen dan samen een interpretatieve dans, naakt uiteraard.

Nu, ik hoop dat u precies vaak genoeg genoemd wordt deze avond om belangrijk gevonden te worden, maar net te weinig om uw ziel ontbloot te voelen.

De formule zal het leren: Pastor Harm Schilder + grapje over piemeltjes van jonge jongens = hihi. Tilburg culturele hoofdstad + iets met de VVD + naamsbekendheid want ik ken d’n dieje – lekker gewoon gebleven = haha.

Deze avond gaat ons hopelijk enorm verlichten. Of de rede hier zegeviert kunt u allen zelf bepalen, we houden na afloop een opiniepeiling in het licht van: ‘uw stem is ook belangrijk’, dit past binnen het thema waar de pamflettisten zo voor gepamfletteerd hebben: Gelijkheid. Het bespotten van de poppetjes kan beginnen!

Het lucht vast wel op, dus in die zin wellicht…. Verlichting.

Esther Porcelijn, 19 jan 2013

(Column voorgedragen tijdens ‘Schuimt’, columnistenbijeenkomst met o.a. Anton Dautzenberg, Luuk Koelman, JACE vd Ven, en Tom America, in jazzpodium Paradox in Tilburg)

More in: Archive O-P, Archive O-P, Porcelijn, Esther, Porcelijn, Esther

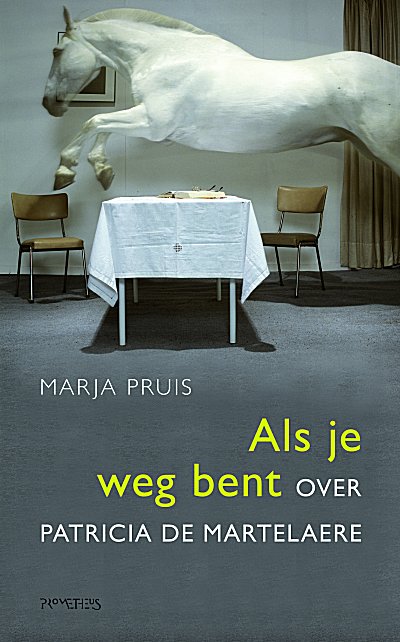

Biografie Patricia de Martelaere

Marja Pruis: Als je weg bent

De Vlaamse schrijfster en filosofe Patricia de Martelaere overleed in 2009 op 51-jarige leeftijd, als een van de belangrijkste schrijvers in het Nederlandse taalgebied, en een van de minst begrepene. Een geladen schrijfster van koele essays en hartstochtelijke romans, zoals het succesvolle Het onverwachte antwoord. Een zeer terughoudende figuur als het ging om belangstelling voor haar persoon en privéleven.

Om in het mysterieuze werk en leven van Patricia de Martelaere door te dringen, neemt Marja Pruis drie rollen op zich: die van biograaf, literair criticus en journalist. Haar diepgravende analyses van de romans en de essays van De Martelaere zijn omlijst met de verhalen van de mensen die haar gekend hebben. Pruis schrijft over de opkomst en het succes van De Martelaere als schrijfster, de verdwijning van haar echtgenoot en haar omarming van het taoïsme – daarbij altijd de link leggend met de thema’s en de verhalen uit haar werk.

Marja Pruis schreef onder meer de veelgeprezen romans De vertrouweling en Atoomgeheimen en is criticus voor De Groene Amsterdammer. Met De Nijhoffs of de gevolgen van een huwelijk toonde zij zich al eerder een onorthodox schrijversbiograaf. Haar meest recente werk, Kus me, straf me. Over lezen en schrijven, liefde en verraad, haalde de shortlist van de ako Literatuurprijs.

Marja Pruis: Als je weg bent – paperback – 192 p. – € 19,95

ISBN 9789044618211 – Uitgeverij Prometheus

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive M-N, Martelaere, Patricia de

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature