Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

.jpg)

Novalis

(Friedrich von Hardenberg, 1772–1802)

Hymnen an die Nacht 5

Über der Menschen weitverbreitete Stämme herrschte vor Zeiten ein eisernes Schicksal mit stummer Gewalt. Eine dunkle, schwere Binde lag um ihre bange Seele – Unendlich war die Erde – der Götter Aufenthalt, und ihre Heymath. Seit Ewigkeiten stand ihr geheimnißvoller Bau. Ueber des Morgens rothen Bergen, in des Meeres heiligem Schooß wohnte die Sonne, das allzündende, lebendige Licht.

Ein alter Riese trug die selige Welt. Fest unter Bergen lagen die Ursöhne der Mutter Erde. Ohnmächtig in ihrer zerstörenden Wuth gegen das neue herrliche Göttergeschlecht und dessen Verwandten, die fröhlichen Menschen. Des Meers dunkle, grüne Tiefe war einer Göttin Schooß. In den krystallenen Grotten schwelgte ein üppiges Volk. Flüsse, Bäume, Blumen und Thiere hatten menschlichen Sinn. Süßer schmeckte der Wein von sichtbarer Jugendfülle geschenkt – ein Gott in den Trauben – eine liebende, mütterliche Göttin, empor wachsend in vollen goldenen Garben – der Liebe heilger Rausch ein süßer Dienst der schönsten Götterfrau – ein ewig buntes Fest der Himmelskinder und der Erdbewohner rauschte das Leben, wie ein Frühling, durch die Jahrhunderte hin – Alle Ge schlechter verehrten kindlich die zarte, tausendfältige Flamme, als das höchste der Welt. Ein Gedanke nur war es, Ein entsetzliches Traumbild,

Das furchtbar zu den frohen Tischen trat

Und das Gemüth in wilde Schrecken hüllte.

Hier wußten selbst die Götter keinen Rath

Der die beklommne Brust mit Trost erfüllte.

Geheimnißvoll war dieses Unholds Pfad

Des Wuth kein Flehn und keine Gabe stillte;

Es war der Tod, der dieses Lustgelag

Mit Angst und Schmerz und Thränen unterbrach.

Auf ewig nun von allem abgeschieden,

Was hier das Herz in süßer Wollust regt,

Getrennt von den Geliebten, die hienieden

Vergebne Sehnsucht, langes Weh bewegt,

Schien matter Traum dem Todten nur beschieden,

Ohnmächtiges Ringen nur ihm auferlegt.

Zerbrochen war die Woge des Genusses

Am Felsen des unendlichen Verdrusses.

Mit kühnem Geist und hoher Sinnenglut

Verschönte sich der Mensch die grause Larve,

Ein sanfter Jüngling löscht das Licht und ruht –

Sanft wird das Ende, wie ein Wehn der Harfe.

Erinnerung schmilzt in kühler Schattenflut,

So sang das Lied dem traurigen Bedarfe.

Doch unenträthselt blieb die ewge Nacht,

Das ernste Zeichen einer fernen Macht.

Zu Ende neigte die alte Welt sich. Des jungen Geschlechts Lustgarten verwelkte – hinauf in den freyeren, wüsten Raum strebten die unkindlichen, wachsenden Menschen. Die Götter verschwanden mit ihrem Gefolge – Einsam und leblos stand die Natur. Mit eiserner Kette band sie die dürre Zahl und das strenge Maaß. Wie in Staub und Lüfte zerfiel in dunkle Worte die unermeßliche Blüthe des Lebens. Entflohn war der beschwörende Glauben, und die allverwandelnde, allverschwisternde Himmelsgenossin, die Fantasie. Unfreundlich blies ein kalter Nordwind über die erstarrte Flur, und die erstarrte Wunderheymath verflog in den Aether. Des Himmels Fernen füllten mit leuchtenden Welten sich. Ins tiefre Heiligthum, in des Gemüths höhern Raum zog mit ihren Mächten die Seele der Welt – zu walten dort bis zum Anbruch der tagenden Weltherrlichkeit. Nicht mehr war das Licht der Götter Aufenthalt und himmlisches Zeichen – den Schleyer der Nacht warfen sie über sich. Die Nacht ward der Offenbarungen mächtiger Schoos – in ihn kehrten die Götter zurück – schlummerten ein, um in neuen herrlichern Gestalten auszugehn über die veränderte Welt. Im Volk, das vor allen verachtet zu früh reif und der seligen Unschuld der Jugend trotzig fremd geworden war, erschien mit niegesehenem Angesicht die neue Welt – In der Armuth dichterischer Hütte – Ein Sohn der ersten Jungfrau und Mutter – Geheimnißvoller Umarmung unendliche Frucht. Des Morgenlands ahndende, blüt[h]enreiche Weisheit erkannte zuerst der neuen Zeit Beginn – Zu des Königs demüthiger Wiege wies ihr ein Stern den Weg. In der weiten Zukunft Namen huldigten sie ihm mit Glanz und Duft, den höchsten Wundern der Natur. Einsam entfaltete das himmlische Herz sich zu einem Blüthenkelch allmächtger Liebe – des Vaters hohem Antlitz zugewandt und ruhend an dem ahndungsselgen Busen der lieblich ernsten Mutter. Mit vergötternder Inbrunst schaute das weissagende Auge des blühenden Kindes auf die Tage der Zukunft, nach seinen Geliebten, den Sprossen seines Götterstamms, unbekümmert über seiner Tage irdisches Schicksal. Bald sammelten die kindlichsten Gemüther von inniger Liebe wundersam ergriffen sich um ihn her. Wie Blumen keimte ein neues fremdes Leben in seiner Nähe. Unerschöpfliche Worte und der Botschaften fröhlichste fielen wie Funken eines göttlichen Geistes von seinen freundlichen Lippen. Von ferner Küste, unter Hellas heiterm Himmel geboren, kam ein Sänger nach Palästina und ergab sein ganzes Herz dem Wunderkinde:

Der Jüngling bist du, der seit langer Zeit

Auf unsern Gräbern steht in tiefen Sinnen;

Ein tröstlich Zeichen in der Dunkelheit –

Der höhern Menschheit freudiges Beginnen.

Was uns gesenkt in tiefe Traurigkeit

Zieht uns mit süßer Sehnsucht nun von hinnen.

Im Tode ward das ewge Leben kund,

Du bist der Tod und machst uns erst gesund.

Der Sänger zog voll Freudigkeit nach Indostan – das Herz von süßer Liebe trunken; und schüttete in feurigen Gesängen es unter jenem milden Himmel aus, daß tausend Herzen sich zu ihm neigten, und die fröhliche Botschaft tausendzweigig emporwuchs. Bald nach des Sängers Abschied ward das köstliche Leben ein Opfer des menschlichen tiefen Verfalls – Er starb in jungen Jahren, weggerissen von der geliebten Welt, von der weinenden Mutter und seinen zagenden Freunden. Der unsäglichen Leiden dunkeln Kelch leerte der liebliche Mund – In entsetzlicher Angst nahte die Stunde der Geburt der neuen Welt. Hart rang er mit des alten Todes Schrecken – Schwer lag der Druck der alten Welt auf ihm. Noch einmal sah er freundlich nach der Mutter – da kam der ewigen Liebe lösende Hand – und er entschlief.

Nur wenig Tage hing ein tiefer Schleyer über das brausende Meer, über das bebende Land – unzählige Thränen weinten die Geliebten – Entsiegelt ward das Geheimniß – himmlische Geister hoben den uralten Stein vom dunkeln Grabe. Engel saßen bey dem Schlummernden – aus seinen Träumen zartgebildet – Erwacht in neuer Götterherrlichkeit erstieg er die Höhe der neugebornen Welt – begrub mit eigner Hand der Alten Leichnam in die verlaßne Höhle, und legte mit allmächtiger Hand den Stein, den keine Macht erhebt, darauf.

Noch weinen deine Lieben Thränen der Freude, Thränen der Rührung und des unendlichen Danks an deinem Grabe – sehn dich noch immer, freudig erschreckt, auferstehn – und sich mit dir; sehn dich weinen mit süßer Inbrunst an der Mutter seligem Busen, ernst mit den Freunden wandeln, Worte sagen, wie vom Baum des Lebens gebrochen; sehen dich eilen mit voller Sehnsucht in des Vaters Arm, bringend die junge Menschheit, und der goldnen Zukunft unversieglichen Becher. Die Mutter eilte bald dir nach – in himmlischem Triumf – Sie war die Erste in der neuen Heymath bey dir. Lange Zeiten entflossen seitdem, und in immer höherm Glanze regte deine neue Schöpfung sich – und tausende zogen aus Schmerzen und Qualen, voll Glauben und Sehnsucht und Treue dir nach – wallen mit dir und der himmlischen Jungfrau im Reiche der Liebe – dienen im Tempel des himmlischen Todes und sind in Ewigkeit dein.

Gehoben ist der Stein –

Die Menschheit ist erstanden –

Wir alle bleiben dein

Und fühlen keine Banden.

Der herbste Kummer fleucht

Vor deiner goldnen Schaale,

Wenn Erd und Leben weicht

Im letzten Abendmahle.

Zur Hochzeit ruft der Tod –

Die Lampen brennen helle –

Die Jungfraun sind zur Stelle –

Um Oel ist keine Noth –

Erklänge doch die Ferne

Von deinem Zuge schon,

Und ruften uns die Sterne

Mit Menschenzung’ und Ton.

Nach dir, Maria, heben

Schon tausend Herzen sich.

In diesem Schattenleben

Verlangten sie nur dich.

Sie hoffen zu genesen

Mit ahndungsvoller Lust –

Drückst du sie, heilges Wesen,

An deine treue Brust.

So manche, die sich glühend

In bittrer Qual verzehrt

Und dieser Welt entfliehend

Nach dir sich hingekehrt;

Die hülfreich uns erschienen

In mancher Noth und Pein –

Wir kommen nun zu ihnen

Um ewig da zu seyn.

Nun weint an keinem Grabe,

Für Schmerz, wer liebend glaubt,

Der Liebe süße Habe

Wird keinem nicht geraubt –

Die Sehnsucht ihm zu lindern,

Begeistert ihn die Nacht –

Von treuen Himmelskindern

Wird ihm sein Herz bewacht.

Getrost, das Leben schreitet

Zum ewgen Leben hin;

Von innrer Glut geweitet

Verklärt sich unser Sinn.

Die Sternwelt wird zerfließen

Zum goldnen Lebenswein,

Wir werden sie genießen

Und lichte Sterne seyn.

Die Lieb’ ist frey gegeben,

Und keine Trennung mehr.

Es wogt das volle Leben

Wie ein unendlich Meer.

Nur Eine Nacht der Wonne –

Ein ewiges Gedicht –

Und unser aller Sonne

Ist Gottes Angesicht.

.jpg)

Novalis poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

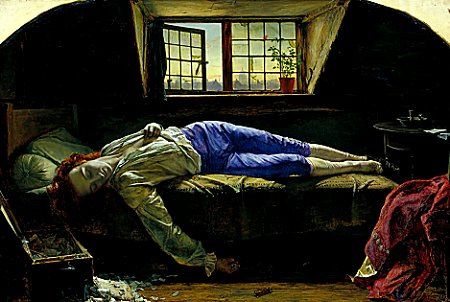

Thomas Chatterton

(1752-1770)

Song from Ælla

SING unto my roundelay,

O drop the briny tear with me;

Dance no more at holyday,

Like a running river be:

My love is dead,

Gone to his death-bed

All under the willow-tree.

Black his cryne [1] as the winter night,

White his rode [2] as the summer snow,

Red his face as the morning light,

Cole he lies in the grave below:

My love is dead,

Gone to his death-bed

All under the willow-tree.

Sweet his tongue as the throstle’s note,

Quick in dance as thought can be,

Deft his tabor, cudgel stout;

O he lies by the willow-tree!

My love is dead,

Gone to his death-bed

All under the willow-tree.

Hark! the raven flaps his wing

In the brier’d dell below;

Hark! the death-owl loud doth sing

To the nightmares, as they go:

My love is dead,

Gone to his death-bed

All under the willow-tree.

See! the white moon shines on high;

Whiter is my true-love’s shroud:

Whiter than the morning sky,

Whiter than the evening cloud:

My love is dead,

Gone to his death-bed

All under the willow-tree.

Here upon my true-love’s grave

Shall the barren flowers be laid;

Not one holy saint to save

All the coldness of a maid:

My love is dead,

Gone to his death-bed

All under the willow-tree.

With my hands I’ll dent the briers

Round his holy corse to gre [3]:

Ouph [4] and fairy, light your fires,

Here my body still shall be:

My love is dead,

Gone to his death-bed

All under the willow-tree.

Come, with acorn-cup and thorn,

Drain my heartès blood away;

Life and all its good I scorn,

Dance by night, or feast by day:

My love is dead,

Gone to his death-bed

All under the willow-tree.

1 cryne – hair – 2 rode – complexion – 3 gre – grow – 4 ouph – elf

Thomas Chatterton poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive C-D, Chatterton, Thomas, Thomas Chatterton

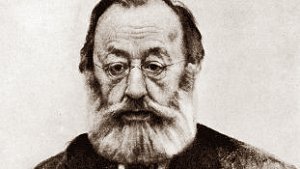

Karl Kraus

(1874-1936)

Der Erotiker

Fiel ihm ein Liebesglück in seinen Schoß,

so war er im Erlebnis gar nicht tüchtig;

und nie genoß er es in vollen Zügen,

wenn es gelang, den Gatten zu betrügen.

Der Glückliche, er war ja ahnungslos –

dagegen jener für ihn eifersüchtig.

Oft hat er, wenn sonst alles hätt’ geklappt,

die Frau beim Ehebruch mit sich ertappt,

und den Beweis hielt er in seinen Armen.

Hier half kein Leugnen. Da er’s selbst gesehn,

und seine Liebe kannte kein Erbarmen.

1920

Karl Kraus poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive K-L, Kraus, Karl

Gabriele D’Annunzio

(1863-1938)

Tu sei la vita

Acqua di monte,

acqua di fonte,

acqua che squilli,

acqua che brilli,

acqua che canti e piangi,

acqua che ridi e muggi,

tu sei la vita e sempre, sempre fuggi.

Gabriele D’Annunzio poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive C-D, D'Annunzio, Gabriele

.jpg)

E u g e n e M a r a i s

(1871-1936)

D a n s v a n d i e r e ë n

O, die dans van ons Suster!

Eers oor die bergtop loer sy skelm,

en haar oge is skaam;

en sy lag saggies,

En van ver af wink sy met die een hand;

haar armbande blink en haar krale skitter;

saggies roep sy,

Sy vertel die winde van die dans

en sy nooi hulle uit, want die werf is wyd

en die bruilof is groot.

Die grootwild jaag uit die vlakte,

hulle dam op die bulttop,

wyd rek hulle die neusgate

en hulle sluk die wind;

en hulle buk, om haar fyn spore in die sand te sien.

Die kleinvolk diep onder die grond

hoor die sleep van haar voete,

en hulle kruip nader en sing saggies;

“Ons Suster! Ons Suster! Jy het gekom! Jy het gekom!”

En haar krale skud,

en haar koperringe blink in die wegraak van die son.

Op haar voorkop is die vuurpluim van die berggier;

sy trap af van die hoogte;

sy sprei die vaal karos met altwee arms uit;

die asem van die wind raak weg.

O, die dans van ons Suster!

Eugene Marais Gedigte

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive M-N, Eugène Marais, Marais, Eugène

Gottfried Keller

(1819–1890)

Unruhe der Nacht

Nun bin ich untreu worden

Der Sonn und ihrem Schein;

Die Nacht, die Nacht soll Dame

Nun meines Herzens sein!

Sie ist von düstrer Schönheit,

Hat ein bleiches Nornengesicht,

Und eine Sternenkrone

Ihr dunkles Haupt umflicht.

Heut ist sie so beklommen,

Unruhig und voller Pein;

Sie denkt wohl an ihre Jugend –

Das muß ein Gedächtnis sein!

Es weht durch alle Täler

Ein Stöhnen, so klagend und bang;

Wie Tränenbäche fließen

Die Quellen vom Bergeshang.

Die schwarzen Fichten sausen

Und wiegen sich her und hin,

Und über die wilde Heide

Verlorene Lichter fliehn.

Dem Himmel bringt ein Ständchen

Das dumpf aufrauschende Meer,

Und über mir zieht ein Gewitter

Mit klingendem Spiele daher.

Es will vielleicht betäuben

Die Nacht den uralten Schmerz?

Und an noch ältere Sünden

Denkt wohl ihr reuiges Herz?

Ich möchte mit ihr plaudern,

Wie man mit dem Liebchen spricht –

Umsonst, in ihrem Grame

Sie sieht und hört mich nicht!

Ich möchte sie gern befragen

Und werde doch immer gestört,

Ob sie vor meiner Geburt schon

Wo meinen Namen gehört?

Sie ist eine alte Sibylle

Und kennt sich selber kaum;

Sie und der Tod und wir alle

Sind Träume von einem Traum.

Ich will mich schlafen legen,

Der Morgenwind schon zieht –

Ihr Trauerweiden am Kirchhof,

Summt mir das Schlummerlied!

Gottfried Keller poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive K-L, Keller, Gottfried

![]()

Georg Trakl

(1887-1914)

Psalm

Karl Kraus zugeeignet

Es ist ein Licht, das der Wind ausgelöscht hat.

Es ist ein Heidekrug, den am Nachmittag ein Betrunkener verläßt.

Es ist ein Weinberg, verbrannt und schwarz mit Löchern voll Spinnen.

Es ist ein Raum, den sie mit Milch getüncht haben.

Der Wahnsinnige ist gestorben. Es ist eine Insel der Südsee,

Den Sonnengott zu empfangen. Man rührt die Trommeln.

Die Männer führen kriegerische Tänze auf.

Die Frauen wiegen die Hüften in Schlinggewächsen und Feuerblumen,

Wenn das Meer singt. O unser verlorenes Paradies.

Die Nymphen haben die goldenen Wälder verlassen.

Man begräbt den Fremden. Dann hebt ein Flimmerregen an.

Der Sohn des Pan erscheint in Gestalt eines Erdarbeiters,

Der den Mittag am glühenden Asphalt verschläft.

Es sind kleine Mädchen in einem Hof in Kleidchen voll herzzerreißender Armut!

Es sind Zimmer, erfüllt von Akkorden und Sonaten.

Es sind Schatten, die sich vor einem erblindeten Spiegel umarmen.

An den Fenstern des Spitals wärmen sich Genesende.

Ein weißer Dampfer am Kanal trägt blutige Seuchen herauf.

Die fremde Schwester erscheint wieder in jemands bösen Träumen.

Ruhend im Haselgebüsch spielt sie mit seinen Sternen.

Der Student, vielleicht ein Doppelgänger, schaut ihr lange vom Fenster nach.

Hinter ihm steht sein toter Bruder, oder er geht die alte Wendeltreppe herab.

Im Dunkel brauner Kastanien verblaßt die Gestalt des jungen Novizen.

Der Garten ist im Abend. Im Kreuzgang flattern die Fledermäuse umher.

Die Kinder des Hausmeisters hören zu spielen auf und suchen das Gold des Himmels.

Endakkorde eines Quartetts. Die kleine Blinde läuft zitternd durch die Allee,

Und später tastet ihr Schatten an kalten Mauern hin, umgeben von Märchen und heiligen Legenden.

Es ist ein leeres Boot, das am Abend den schwarzen Kanal heruntertreibt.

In der Düsternis des alten Asyls verfallen menschliche Ruinen.

Die toten Waisen liegen an der Gartenmauer.

Aus grauen Zimmern treten Engel mit kotgefleckten Flügeln.

Würmer tropfen von ihren vergilbten Lidern.

Der Platz vor der Kirche ist finster und schweigsam, wie in den Tagen der Kindheit.

Auf silbernen Sohlen gleiten frühere Leben vorbei

Und die Schatten der Verdammten steigen zu den seufzenden Wassern nieder.

In seinem Grab spielt der weiße Magier mit seinen Schlangen.

Schweigsam über der Schädelstätte öffnen sich Gottes goldene Augen.

Georg Trakl poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Kraus, Karl, Trakl, Georg

Catherine Pozzi

(1884-1934)

Ave

Très haut amour, s’il se peut que je meure

Sans avoir su d’où je vous possédais,

En quel soleil était votre demeure

En quel passé votre temps, en quelle heure

Je vous aimais,

Très haut amour qui passez la mémoire,

Feu sans foyer dont j’ai fait tout mon jour,

En quel destin vous traciez mon histoire,

En quel sommeil se voyait votre gloire,

Ô mon séjour..

Quand je serai pour moi-même perdue

Et divisée à l’abîme infini,

Infiniment, quand je serai rompue,

Quand le présent dont je suis revêtue

Aura trahi,

Par l’univers en mille corps brisée,

De mille instants non rassemblés encor,

De cendre aux cieux jusqu’au néant vannée,

Vous referez pour une étrange année

Un seul trésor

Vous referez mon nom et mon image

De mille corps emportés par le jour,

Vive unité sans nom et sans visage,

Coeur de l’esprit, ô centre du mirage

Très haut amour.

Catherine Pozzi poésie

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive O-P, Pozzi, Catherine

Esther Porcelijn

De superstorm

De keren dat ik verwaai

zijn gevaarlijk voor ons al.

Vluchten doet zelfs de kraai

op het dakje, opgeschrikt door vreemd geschal.

Weggedoken onder een stoel.

De krant vliegt in het rond,

mijn haren overeind bij het gevoel

dat ik dove woorden pers uit mijn mond.

Gegil verstomt bij elke schreeuw

van menig man die loopt op straat.

De kraai zoekt schutting bij een meeuw.

De weerman heeft geen paraplu paraat.

Als ik gedwongen word de oorsprong van dit noodweer op te sporen

kijk ik naast me, zie mijn vriendje, met benen opgetrokken, dromend

over chili-con-carne.

Esther Porcelijn gedicht

uit de nieuwe bundel: De keren dat ik verwaai

De keren dat ik verwaai is verkrijgbaar

of te bestellen via de reguliere boekhandel

of via uitgeverij teleXpress – www.telespress.nl

ISBN/EAN: 978-90-76937-44-1

Prijs: 15 euro

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive O-P, Art & Literature News, Porcelijn, Esther

MARTIN BEVERSLUIS

Tijdbom

Woorden zijn gordijnen die je toedoet

zodra het spektakel is afgelopen het

waren mooie beelden een stuk of acht

jongens die in het midden van de nacht

iemand aanvielen en helemaal verrot

schopten na de daden komen dan altijd

de woorden die van afschuw het eerst

dan is het gevaar geweken kunnen we

de toedracht gaan verklaren deze tijden

zijn van teruggang en onbegrip dat vatten

we onvermijdelijk persoonlijk op hoe kan

dit mij overkomen een frustratio die er

toe doet die smeekt om een uitlaatklep

het grote verklaren is begonnen na ieder

conflict begrijpen we meer tot begrip ook

niet meer helpt en het recht van de sterkste

geldt deze woorden zijn gordijnen die

je dicht doet als je het denkraam sluit

een tijdbom wordt terloops ontploft.

Martin Beversluis poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Beversluis, Martin

William Butler Yeats

(1865 – 1939)

The Heart of the Woman

O what to me the little room

That was brimmed up with prayer and rest;

He bade me out into the gloom,

And my breast lies upon his breast.

O what to me my mother’s care,

The house where I was safe and warm;

The shadowy blossom of my hair

Will hide us from the bitter storm.

O hiding hair and dewy eyes,

I am no more with life and death,

My heart upon his warm heart lies,

My breath is mixed into his breath.

William Butler Yeats poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive Y-Z, Yeats, William Butler

James Joyce

(1882-1941)

A Little Cloud

Eight years before he had seen his friend off at the North Wall and wished him godspeed. Gallaher had got on. You could tell that at once by his travelled air, his well-cut tweed suit, and fearless accent. Few fellows had talents like his and fewer still could remain unspoiled by such success. Gallaher’s heart was in the right place and he had deserved to win. It was something to have a friend like that.

Little Chandler’s thoughts ever since lunch-time had been of his meeting with Gallaher, of Gallaher’s invitation and of the great city London where Gallaher lived. He was called Little Chandler because, though he was but slightly under the average stature, he gave one the idea of being a little man. His hands were white and small, his frame was fragile, his voice was quiet and his manners were refined. He took the greatest care of his fair silken hair and moustache and used perfume discreetly on his handkerchief. The half-moons of his nails were perfect and when he smiled you caught a glimpse of a row of childish white teeth.

As he sat at his desk in the King’s Inns he thought what changes those eight years had brought. The friend whom he had known under a shabby and necessitous guise had become a brilliant figure on the London Press. He turned often from his tiresome writing to gaze out of the office window. The glow of a late autumn sunset covered the grass plots and walks. It cast a shower of kindly golden dust on the untidy nurses and decrepit old men who drowsed on the benches; it flickered upon all the moving figures, on the children who ran screaming along the gravel paths and on everyone who passed through the gardens. He watched the scene and thought of life; and (as always happened when he thought of life) he became sad. A gentle melancholy took possession of him. He felt how useless it was to struggle against fortune, this being the burden of wisdom which the ages had bequeathed to him.

He remembered the books of poetry upon his shelves at home. He had bought them in his bachelor days and many an evening, as he sat in the little room off the hall, he had been tempted to take one down from the bookshelf and read out something to his wife. But shyness had always held him back; and so the books had remained on their shelves. At times he repeated lines to himself and this consoled him.

When his hour had struck he stood up and took leave of his desk and of his fellow-clerks punctiliously. He emerged from under the feudal arch of the King’s Inns, a neat modest figure, and walked swiftly down Henrietta Street. The golden sunset was waning and the air had grown sharp. A horde of grimy children populated the street. They stood or ran in the roadway or crawled up the steps before the gaping doors or squatted like mice upon the thresholds. Little Chandler gave them no thought. He picked his way deftly through all that minute vermin-like life and under the shadow of the gaunt spectral mansions in which the old nobility of Dublin had roystered. No memory of the past touched him, for his mind was full of a present joy.

He had never been in Corless’s but he knew the value of the name. He knew that people went there after the theatre to eat oysters and drink liqueurs; and he had heard that the waiters there spoke French and German. Walking swiftly by at night he had seen cabs drawn up before the door and richly dressed ladies, escorted by cavaliers, alight and enter quickly. They wore noisy dresses and many wraps. Their faces were powdered and they caught up their dresses, when they touched earth, like alarmed Atalantas. He had always passed without turning his head to look. It was his habit to walk swiftly in the street even by day and whenever he found himself in the city late at night he hurried on his way apprehensively and excitedly. Sometimes, however, he courted the causes of his fear. He chose the darkest and narrowest streets and, as he walked boldly forward, the silence that was spread about his footsteps troubled him, the wandering, silent figures troubled him; and at times a sound of low fugitive laughter made him tremble like a leaf.

He turned to the right towards Capel Street. Ignatius Gallaher on the London Press! Who would have thought it possible eight years before? Still, now that he reviewed the past, Little Chandler could remember many signs of future greatness in his friend. People used to say that Ignatius Gallaher was wild Of course, he did mix with a rakish set of fellows at that time. drank freely and borrowed money on all sides. In the end he had got mixed up in some shady affair, some money transaction: at least, that was one version of his flight. But nobody denied him talent. There was always a certain . . . something in Ignatius Gallaher that impressed you in spite of yourself. Even when he was out at elbows and at his wits’ end for money he kept up a bold face. Little Chandler remembered (and the remembrance brought a slight flush of pride to his cheek) one of Ignatius Gallaher’s sayings when he was in a tight corner

“Half time now, boys,” he used to say light-heartedly. “Where’s my considering cap?”

That was Ignatius Gallaher all out; and, damn it, you couldn’t but admire him for it.

Little Chandler quickened his pace. For the first time in his life he felt himself superior to the people he passed. For the first time his soul revolted against the dull inelegance of Capel Street. There was no doubt about it: if you wanted to succeed you had to go away. You could do nothing in Dublin. As he crossed Grattan Bridge he looked down the river towards the lower quays and pitied the poor stunted houses. They seemed to him a band of tramps, huddled together along the riverbanks, their old coats covered with dust and soot, stupefied by the panorama of sunset and waiting for the first chill of night bid them arise, shake themselves and begone. He wondered whether he could write a poem to express his idea. Perhaps Gallaher might be able to get it into some London paper for him. Could he write something original? He was not sure what idea he wished to express but the thought that a poetic moment had touched him took life within him like an infant hope. He stepped onward bravely.

Every step brought him nearer to London, farther from his own sober inartistic life. A light began to tremble on the horizon of his mind. He was not so old, thirty-two. His temperament might be said to be just at the point of maturity. There were so many different moods and impressions that he wished to express in verse. He felt them within him. He tried weigh his soul to see if it was a poet’s soul. Melancholy was the dominant note of his temperament, he thought, but it was a melancholy tempered by recurrences of faith and resignation and simple joy. If he could give expression to it in a book of poems perhaps men would listen. He would never be popular: he saw that. He could not sway the crowd but he might appeal to a little circle of kindred minds. The English critics, perhaps, would recognise him as one of the Celtic school by reason of the melancholy tone of his poems; besides that, he would put in allusions. He began to invent sentences and phrases from the notice which his book would get. “Mr. Chandler has the gift of easy and graceful verse.” . . . “wistful sadness pervades these poems.” . . . “The Celtic note.” It was a pity his name was not more Irish-looking. Perhaps it would be better to insert his mother’s name before the surname: Thomas Malone Chandler, or better still: T. Malone Chandler. He would speak to Gallaher about it.

He pursued his revery so ardently that he passed his street and had to turn back. As he came near Corless’s his former agitation began to overmaster him and he halted before the door in indecision. Finally he opened the door and entered.

The light and noise of the bar held him at the doorways for a few moments. He looked about him, but his sight was confused by the shining of many red and green wine-glasses The bar seemed to him to be full of people and he felt that the people were observing him curiously. He glanced quickly to right and left (frowning slightly to make his errand appear serious), but when his sight cleared a little he saw that nobody had turned to look at him: and there, sure enough, was Ignatius Gallaher leaning with his back against the counter and his feet planted far apart.

“Hallo, Tommy, old hero, here you are! What is it to be? What will you have? I’m taking whisky: better stuff than we get across the water. Soda? Lithia? No mineral? I’m the same Spoils the flavour. . . . Here, garçon, bring us two halves of malt whisky, like a good fellow. . . . Well, and how have you been pulling along since I saw you last? Dear God, how old we’re getting! Do you see any signs of aging in me, eh, what? A little grey and thin on the top, what?”

Ignatius Gallaher took off his hat and displayed a large closely cropped head. His face was heavy, pale and cleanshaven. His eyes, which were of bluish slate-colour, relieved his unhealthy pallor and shone out plainly above the vivid orange tie he wore. Between these rival features the lips appeared very long and shapeless and colourless. He bent his head and felt with two sympathetic fingers the thin hair at the crown. Little Chandler shook his head as a denial. Ignatius Galaher put on his hat again.

“It pulls you down,” be said, “Press life. Always hurry and scurry, looking for copy and sometimes not finding it: and then, always to have something new in your stuff. Damn proofs and printers, I say, for a few days. I’m deuced glad, I can tell you, to get back to the old country. Does a fellow good, a bit of a holiday. I feel a ton better since I landed again in dear dirty Dublin. . . . Here you are, Tommy. Water? Say when.”

Little Chandler allowed his whisky to be very much diluted.

“You don’t know what’s good for you, my boy,” said Ignatius Gallaher. “I drink mine neat.”

“I drink very little as a rule,” said Little Chandler modestly. “An odd half-one or so when I meet any of the old crowd: that’s all.”

“Ah well,” said Ignatius Gallaher, cheerfully, “here’s to us and to old times and old acquaintance.”

They clinked glasses and drank the toast.

“I met some of the old gang today,” said Ignatius Gallaher. “O’Hara seems to be in a bad way. What’s he doing?”

“Nothing,” said Little Chandler. “He’s gone to the dogs.”

“But Hogan has a good sit, hasn’t he?”

“Yes; he’s in the Land Commission.”

“I met him one night in London and he seemed to be very flush. . . . Poor O’Hara! Boose, I suppose?”

“Other things, too,” said Little Chandler shortly.

Ignatius Gallaher laughed.

“Tommy,” he said, “I see you haven’t changed an atom. You’re the very same serious person that used to lecture me on Sunday mornings when I had a sore head and a fur on my tongue. You’d want to knock about a bit in the world. Have you never been anywhere even for a trip?”

“I’ve been to the Isle of Man,” said Little Chandler.

Ignatius Gallaher laughed.

“The Isle of Man!” he said. “Go to London or Paris: Paris, for choice. That’d do you good.”

“Have you seen Paris?”

“I should think I have! I’ve knocked about there a little.”

“And is it really so beautiful as they say?” asked Little Chandler.

He sipped a little of his drink while Ignatius Gallaher finished his boldly.

“Beautiful?” said Ignatius Gallaher, pausing on the word and on the flavour of his drink. “It’s not so beautiful, you know. Of course, it is beautiful. . . . But it’s the life of Paris; that’s the thing. Ah, there’s no city like Paris for gaiety, movement, excitement. . . . ”

Little Chandler finished his whisky and, after some trouble, succeeded in catching the barman’s eye. He ordered the same again.

“I’ve been to the Moulin Rouge,” Ignatius Gallaher continued when the barman had removed their glasses, “and I’ve been to all the Bohemian cafes. Hot stuff! Not for a pious chap like you, Tommy.”

Little Chandler said nothing until the barman returned with two glasses: then he touched his friend’s glass lightly and reciprocated the former toast. He was beginning to feel somewhat disillusioned. Gallaher’s accent and way of expressing himself did not please him. There was something vulgar in his friend which he had not observed before. But perhaps it was only the result of living in London amid the bustle and competition of the Press. The old personal charm was still there under this new gaudy manner. And, after all, Gallaher had lived, he had seen the world. Little Chandler looked at his friend enviously.

“Everything in Paris is gay,” said Ignatius Gallaher. “They believe in enjoying life, and don’t you think they’re right? If you want to enjoy yourself properly you must go to Paris. And, mind you, they’ve a great feeling for the Irish there. When they heard I was from Ireland they were ready to eat me, man.”

Little Chandler took four or five sips from his glass.

“Tell me,” he said, “is it true that Paris is so . . . immoral as they say?”

Ignatius Gallaher made a catholic gesture with his right arm.

“Every place is immoral,” he said. “Of course you do find spicy bits in Paris. Go to one of the students’ balls, for instance. That’s lively, if you like, when the cocottes begin to let themselves loose. You know what they are, I suppose?”

“I’ve heard of them,” said Little Chandler.

Ignatius Gallaher drank off his whisky and shook his had.

“Ah,” he said, “you may say what you like. There’s no woman like the Parisienne, for style, for go.”

“Then it is an immoral city,” said Little Chandler, with timid insistence, “I mean, compared with London or Dublin?”

“London!” said Ignatius Gallaher. “It’s six of one and half-a-dozen of the other. You ask Hogan, my boy. I showed him a bit about London when he was over there. He’d open your eye. . . . I say, Tommy, don’t make punch of that whisky: liquor up.”

“No, really. . . . ”

“O, come on, another one won’t do you any harm. What is it? The same again, I suppose?”

“Well . . . all right.”

“François, the same again. . . . Will you smoke, Tommy?”

Ignatius Gallaher produced his cigar-case. The two friends lit their cigars and puffed at them in silence until their drinks were served.

“I’ll tell you my opinion,” said Ignatius Gallaher, emerging after some time from the clouds of smoke in which he had taken refuge, “it’s a rum world. Talk of immorality! I’ve heard of cases, what am I saying?, I’ve known them: cases of . . . immorality. . . . ”

Ignatius Gallaher puffed thoughtfully at his cigar and then, in a calm historian’s tone, he proceeded to sketch for his friend some pictures of the corruption which was rife abroad. He summarised the vices of many capitals and seemed inclined to award the palm to Berlin. Some things he could not vouch for (his friends had told him), but of others he had had personal experience. He spared neither rank nor caste. He revealed many of the secrets of religious houses on the Continent and described some of the practices which were fashionable in high society and ended by telling, with details, a story about an English duchess, a story which he knew to be true. Little Chandler as astonished.

“Ah, well,” said Ignatius Gallaher, “here we are in old jog-along Dublin where nothing is known of such things.”

“How dull you must find it,” said Little Chandler, “after all the other places you’ve seen!”

Well,” said Ignatius Gallaher, “it’s a relaxation to come over here, you know. And, after all, it’s the old country, as they say, isn’t it? You can’t help having a certain feeling for it. That’s human nature. . . . But tell me something about yourself. Hogan told me you had . . . tasted the joys of connubial bliss. Two years ago, wasn’t it?”

Little Chandler blushed and smiled.

“Yes,” he said. “I was married last May twelve months.”

“I hope it’s not too late in the day to offer my best wishes,” said Ignatius Gallaher. “I didn’t know your address or I’d have done so at the time.”

He extended his hand, which Little Chandler took.

“Well, Tommy,” he said, “I wish you and yours every joy in life, old chap, and tons of money, and may you never die till I shoot you. And that’s the wish of a sincere friend, an old friend. You know that?”

“I know that,” said Little Chandler.

“Any youngsters?” said Ignatius Gallaher.

Little Chandler blushed again.

“We have one child,” he said.

“Son or daughter?”

“A little boy.”

Ignatius Gallaher slapped his friend sonorously on the back.

“Bravo,” he said, “I wouldn’t doubt you, Tommy.”

Little Chandler smiled, looked confusedly at his glass and bit his lower lip with three childishly white front teeth.

“I hope you’ll spend an evening with us,” he said, “before you go back. My wife will be delighted to meet you. We can have a little music and, , ”

“Thanks awfully, old chap,” said Ignatius Gallaher, “I’m sorry we didn’t meet earlier. But I must leave tomorrow night.”

“Tonight, perhaps . . . ?”

“I’m awfully sorry, old man. You see I’m over here with another fellow, clever young chap he is too, and we arranged to go to a little card-party. Only for that . . . ”

“O, in that case . . . ”

“But who knows?” said Ignatius Gallaher considerately. “Next year I may take a little skip over here now that I’ve broken the ice. It’s only a pleasure deferred.”

“Very well,” said Little Chandler, “the next time you come we must have an evening together. That’s agreed now, isn’t it?”

“Yes, that’s agreed,” said Ignatius Gallaher. “Next year if I come, parole d’honneur.”

“And to clinch the bargain,” said Little Chandler, “we’ll just have one more now.”

Ignatius Gallaher took out a large gold watch and looked a it.

“Is it to be the last?” he said. “Because you know, I have an a.p.”

“O, yes, positively,” said Little Chandler.

“Very well, then,” said Ignatius Gallaher, “let us have another one as a deoc an doruis, that’s good vernacular for a small whisky, I believe.”

Little Chandler ordered the drinks. The blush which had risen to his face a few moments before was establishing itself. A trifle made him blush at any time: and now he felt warm and excited. Three small whiskies had gone to his head and Gallaher’s strong cigar had confused his mind, for he was a delicate and abstinent person. The adventure of meeting Gallaher after eight years, of finding himself with Gallaher in Corless’s surrounded by lights and noise, of listening to Gallaher’s stories and of sharing for a brief space Gallaher’s vagrant and triumphant life, upset the equipoise of his sensitive nature. He felt acutely the contrast between his own life and his friend’s and it seemed to him unjust. Gallaher was his inferior in birth and education. He was sure that he could do something better than his friend had ever done, or could ever do, something higher than mere tawdry journalism if he only got the chance. What was it that stood in his way? His unfortunate timidity He wished to vindicate himself in some way, to assert his manhood. He saw behind Gallaher’s refusal of his invitation. Gallaher was only patronising him by his friendliness just as he was patronising Ireland by his visit.

The barman brought their drinks. Little Chandler pushed one glass towards his friend and took up the other boldly.

“Who knows?” he said, as they lifted their glasses. “When you come next year I may have the pleasure of wishing long life and happiness to Mr. and Mrs. Ignatius Gallaher.”

Ignatius Gallaher in the act of drinking closed one eye expressively over the rim of his glass. When he had drunk he smacked his lips decisively, set down his glass and said:

“No blooming fear of that, my boy. I’m going to have my fling first and see a bit of life and the world before I put my head in the sack, if I ever do.”

“Some day you will,” said Little Chandler calmly.

Ignatius Gallaher turned his orange tie and slate-blue eyes full upon his friend.

“You think so?” he said.

“You’ll put your head in the sack,” repeated Little Chandler stoutly, “like everyone else if you can find the girl.”

He had slightly emphasised his tone and he was aware that he had betrayed himself; but, though the colour had heightened in his cheek, he did not flinch from his friend’s gaze. Ignatius Gallaher watched him for a few moments and then said:

“If ever it occurs, you may bet your bottom dollar there’ll be no mooning and spooning about it. I mean to marry money. She’ll have a good fat account at the bank or she won’t do for me.”

Little Chandler shook his head.

“Why, man alive,” said Ignatius Gallaher, vehemently, “do you know what it is? I’ve only to say the word and tomorrow I can have the woman and the cash. You don’t believe it? Well, I know it. There are hundreds, what am I saying?, thousands of rich Germans and Jews, rotten with money, that’d only be too glad. . . . You wait a while my boy. See if I don’t play my cards properly. When I go about a thing I mean business, I tell you. You just wait.”

He tossed his glass to his mouth, finished his drink and laughed loudly. Then he looked thoughtfully before him and said in a calmer tone:

“But I’m in no hurry. They can wait. I don’t fancy tying myself up to one woman, you know.”

He imitated with his mouth the act of tasting and made a wry face.

“Must get a bit stale, I should think,” he said.

Little Chandler sat in the room off the hall, holding a child in his arms. To save money they kept no servant but Annie’s young sister Monica came for an hour or so in the morning and an hour or so in the evening to help. But Monica had gone home long ago. It was a quarter to nine. Little Chandler had come home late for tea and, moreover, he had forgotten to bring Annie home the parcel of coffee from Bewley’s. Of course she was in a bad humour and gave him short answers. She said she would do without any tea but when it came near the time at which the shop at the corner closed she decided to go out herself for a quarter of a pound of tea and two pounds of sugar. She put the sleeping child deftly in his arms and said:

“Here. Don’t waken him.”

A little lamp with a white china shade stood upon the table and its light fell over a photograph which was enclosed in a frame of crumpled horn. It was Annie’s photograph. Little Chandler looked at it, pausing at the thin tight lips. She wore the pale blue summer blouse which he had brought her home as a present one Saturday. It had cost him ten and elevenpence; but what an agony of nervousness it had cost him! How he had suffered that day, waiting at the shop door until the shop was empty, standing at the counter and trying to appear at his ease while the girl piled ladies’ blouses before him, paying at the desk and forgetting to take up the odd penny of his change, being called back by the cashier, and finally, striving to hide his blushes as he left the shop by examining the parcel to see if it was securely tied. When he brought the blouse home Annie kissed him and said it was very pretty and stylish; but when she heard the price she threw the blouse on the table and said it was a regular swindle to charge ten and elevenpence for it. At first she wanted to take it back but when she tried it on she was delighted with it, especially with the make of the sleeves, and kissed him and said he was very good to think of her.

Hm! . . .

He looked coldly into the eyes of the photograph and they answered coldly. Certainly they were pretty and the face itself was pretty. But he found something mean in it. Why was it so unconscious and ladylike? The composure of the eyes irritated him. They repelled him and defied him: there was no passion in them, no rapture. He thought of what Gallaher had said about rich Jewesses. Those dark Oriental eyes, he thought, how full they are of passion, of voluptuous longing! . . . Why had he married the eyes in the photograph?

He caught himself up at the question and glanced nervously round the room. He found something mean in the pretty furniture which he had bought for his house on the hire system. Annie had chosen it herself and it reminded him of her. It too was prim and pretty. A dull resentment against his life awoke within him. Could he not escape from his little house? Was it too late for him to try to live bravely like Gallaher? Could he go to London? There was the furniture still to be paid for. If he could only write a book and get it published, that might open the way for him.

A volume of Byron’s poems lay before him on the table. He opened it cautiously with his left hand lest he should waken the child and began to read the first poem in the book:

Hushed are the winds and still the evening gloom,

Not e’en a Zephyr wanders through the grove,

Whilst I return to view my Margaret’s tomb

And scatter flowers on the dust I love.

He paused. He felt the rhythm of the verse about him in the room. How melancholy it was! Could he, too, write like that, express the melancholy of his soul in verse? There were so many things he wanted to describe: his sensation of a few hours before on Grattan Bridge, for example. If he could get back again into that mood. . . .

The child awoke and began to cry. He turned from the page and tried to hush it: but it would not be hushed. He began to rock it to and fro in his arms but its wailing cry grew keener. He rocked it faster while his eyes began to read the second stanza:

Within this narrow cell reclines her clay,

That clay where once . . .

It was useless. He couldn’t read. He couldn’t do anything. The wailing of the child pierced the drum of his ear. It was useless, useless! He was a prisoner for life. His arms trembled with anger and suddenly bending to the child’s face he shouted:

“Stop!”

The child stopped for an instant, had a spasm of fright and began to scream. He jumped up from his chair and walked hastily up and down the room with the child in his arms. It began to sob piteously, losing its breath for four or five seconds, and then bursting out anew. The thin walls of the room echoed the sound. He tried to soothe it but it sobbed more convulsively. He looked at the contracted and quivering face of the child and began to be alarmed. He counted seven sobs without a break between them and caught the child to his breast in fright. If it died! . . .

The door was burst open and a young woman ran in, panting.

“What is it? What is it?” she cried.

The child, hearing its mother’s voice, broke out into a paroxysm of sobbing.

“It’s nothing, Annie . . . it’s nothing. . . . He began to cry . . . ”

She flung her parcels on the floor and snatched the child from him.

“What have you done to him?” she cried, glaring into his face.

Little Chandler sustained for one moment the gaze of her eyes and his heart closed together as he met the hatred in them. He began to stammer:

“It’s nothing. . . . He . . . he began to cry. . . . I couldn’t . . . I didn’t do anything. . . . What?”

Giving no heed to him she began to walk up and down the room, clasping the child tightly in her arms and murmuring:

“My little man! My little mannie! Was ’ou frightened, love? . . . There now, love! There now!… Lambabaun! Mamma’s little lamb of the world! . . . There now!”

Little Chandler felt his cheeks suffused with shame and he stood back out of the lamplight. He listened while the paroxysm of the child’s sobbing grew less and less; and tears of remorse started to his eyes.

James Joyce stories

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive I-J, Joyce, James, Joyce, James

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature