Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

I n M e m o r i a m A d W i l l e m e n

Jasper Mikkers

Teruggebracht Vuur (1)(2)

alle beelden zijn tot rust gekomen

het sneeuwt niet meer, niet in het hoofd, niet achter vensterglas

persen, lijsten, kasten, stiften en penselen

het water in de leiding: alles houdt zich stil

het ontbreekt de wil te zijn nu hij er niet meer is

door de verwildering van vlees is wie hij was

vermenigvuldigd tot een handvol gras

alle beelden zijn tot rust gekomen

de boeren die naar huis toe liepen na het planten van de rijst

de spelerstroep, halfweg een touwbrug over een ravijn

de vlokken die nog vielen, hangen roerloos in de lucht

nu hij is gestopt met dromen

geen naakt zijn netvlies raakt

schoonheid vond hier zwart en rood

geen wit van borsten, bil en dij wordt nog gevangen

in gebogen lijnen: wie stopt nu het verdwijnen

het verdrogen van de jonge vormen in de tijd, wie houdt

het woelen van verlangen ons voor ogen, legt

eeuwig voelen vast

een vuur teruggebracht tot minder dan miniatuur

geen tijd stroomt door zijn vlees, beweegt zijn hand

zijn stem heeft zich verzacht tot minder nog dan hees

zijn bril, een venster dat vergrootte wat zich aan het oog

onttrekken wou, een omgestoten whiskyfles en tekenblok

liggen op tafel, naast zijn broeksriem en een sok

(1) Dit gedicht schreef ik in mijn functie van stadsdichter.

(2) Op 24 september is kunstenaar Ad Willemen overleden. Hij was tekenaar, etser, lithograaf en fotograaf en maakte gouaches. Hij was de leermeester van Reinoud van Vugt en Marc Mulders, exposeerde in binnen- en buitenland en won prijzen. Hij gaf les aan het Koning Willem II College. Met zijn miniaturen van klassieke schilderijen en naakttekeningen (Het geheime oeuvre van Adriaan Willemen) verwierf hij een grote bekendheid.

Jasper Mikkers is stadsdichter van Tilburg

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Ad Willemen, Archive M-N, In Memoriam, Mikkers, Jasper

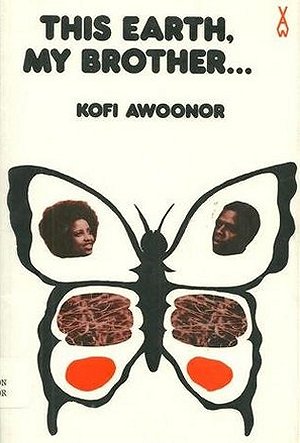

Ghanaian poet Kofi Awoonor

died during attack at Nairobian shopping mall

23 september 2013

Ghanaian poet Professor Kofi Awoonor has died during the attack at Nairobian shopping centre Westgate Mall. He died on Saturday, aged 78, from injuries sustained in the attack in Nairobi.

Kofi Awoonor was in Nairobi to speak at the Storymoja Hay Festival, a four-day international litarary festival. Performers were also Ghanaian poets Nii Parkes and Kwame Dawes. Awoonor was due to perform on this festival on Saturday evening.

Awoonor was born in 1935 and became known for his poetry, inspired by the oral poetry of his native Ewe tribe. Awoonor gained a masters degree in literature at London University in 1970. His second collection of poetry, Night of My Blood, was published in 1971, a series of poems that explore his roots of colonialism and foreign rule in Africa.

His son was also shot, but has later been discharged from hospital.

Kofi Awoonor

Songs of Sorrow

I

Dzogbese Lisa has treated me thus

It has led me among the sharps of the forest

Returning is not possible

And going forward is a great difficulty

The affairs of this world are like the chameleon faeces

Into which I have stepped

When I clean it cannot go.

I am on the world’s extreme corner,

I am not sitting in the row with the eminent

But those who are lucky

Sit in the middle and forget

I am on the world’s extreme corner

I can only go beyond and forget.

My people, I have been somewhere

If I turn here, the rain beats me

If I turn there the sun burns me

The firewood of this world

Is for only those who can take heart

That is why not all can gather it.

The world is not good for anybody

But you are so happy with your fate;

Alas! the travelers are back

All covered with debt.

II

Something has happened to me

The things so great that I cannot weep

I have no sons to fire the gun when I die

And no daughter to wail when I close my mouth

I have wandered on the wilderness

The great wilderness men call life

The rain has beaten me,

And the sharp stumps cut as keen as knives

I shall go beyond and rest.

I have no kin and no brother,

Death has made war upon our house;

And Kpeti’s great household is no more,

Only the broken fence stands;

And those who dared not look in his face

Have come out as men.

How well their pride is with them.

Let those gone before take note

They have treated their offspring badly.

What is the wailing for?

Somebody is dead. Agosu himself

Alas! a snake has bitten me

My right arm is broken,

And the tree on which I lean is fallen.

Agosi if you go tell them,

Tell Nyidevu, Kpeti, and Kove

That they have done us evil;

Tell them their house is falling

And the trees in the fence

Have been eaten by termites

That the martels curse them.

Ask them why they idle there

While we suffer, and eat sand.

And the crow and the vulture

Hover always above our broken fences

And strangers walk over our portion.

Publications

1964 Rediscovery and Other Poems (poetry)

1971 Night of My Blood (poetry)

1971 This Earth, My Brother … An Allegorical Tale of Africa (novel)

1972 Come Back, Ghana

1973 Ride Me, Memory (poetry)

1975 The Breast of the Earth: A Survey of the History, Culture and Literature of Africa South of the Sahara

1978 The House by the Sea (poetry)

1984 The Ghana Revolution: A Background Account from a Personal Perspective

1987 Until the Morning After: Collected Poems (poetry)

1990 Ghana: A Political History from Pre-European to Modern Times

1992 Comes the Voyager at Last: A Tale of Return to Africa (novel)

1992 The Latin American and Caribbean Notebook (poetry)

1994 Africa, the Marginalized Continent

2002 Herding the Lost Lamb (poetry)

2006 The African Predicament: Collected Essays

# More Ghanaian poetry on website POETRY FOUNDATION GHANA

# Website Hay Festival Nairobi

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, In Memoriam

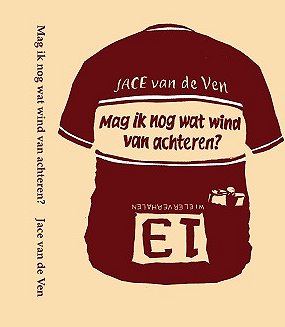

Nieuwe wielerverhalen van

JACE van de Ven:

Mag ik nog wat wind van achteren?

Op vrijdag de dertiende, de ultieme datum waarop Tilburg het jaar 013 viert, presenteerde de eerste stadsdichter van Tilburg en voormalig journalist en columnschrijver JACE van de Ven het boek `Mag ik nog wat wind van achteren` in Boekhandel Livius in Tilburg. Dat gebeurt na sluitingsuur om 20,00 uur. Iedereen is welkom. Het boek bevat dertien vlot geschreven wielerverhalen, gebaseerd op voorvallen in veertig jaar fietservaring, waarin JACE ongeveer 100.000 kilometer aflegde.

Van de Ven is een geboren verteller met een scherp observatievermogen en een continue verwondering over de menselijke natuur. Zijn belevenissen en gedachten verwerkt hij sinds enkele jaren in korte fietsverhalen die soms hilarisch en relativerend zijn, dan weer ontroerend en serieus van toon. Zo neemt hij je in het nieuwe boek in gedachten mee langs de mooiste dorpjes van de Ardennen, legt hij uit wat er nodig is om een profwielrenner te worden, laat hij de lezer kennis maken met de kleurrijke figuren die hij onderweg ontmoet en ontroert hij met een verhaal waarin hij terugdenkt aan een wedstrijdje fietsen tegen zijn broer Toon, die ondertussen is overleden aan de gevolgen van kanker.

Van de Ven is een opvallende verschijning in het peloton van wielerauteurs. Zijn forse postuur en woeste baard hebben hem de bijnaam Raspoetin bezorgd. Verwacht geen geschoren benen, carbon frames en wetenschappelijk verantwoorde sportdrank. Van de Ven is eerder de bourgondische fietser die bovenop een col stopt om van een wijds uitzicht te genieten en eenmaal beneden… van de gastvrijheid van de lokale horeca.

Van de Ven leest regelmatig fietsverhalen voor bij feesten van wielerverenigingen, in de wielercafés van Oss en Bladel en op parties bij oud-wielrenners. ‘Mag ik nog wat wind van achteren?’ is zijn antwoord op de vele verzoeken om zijn teksten eens in boekvorm uit te brengen.

‘Mag ik nog wat wind van achteren?’ (ISBN/EAN: 978-94-90484-05-7 NUR: 303) kent een mooie omslag van Ivo van Leeuwen, het boek is vormgegeven door Chris Leenaars, ReflexBlue en geïllustreerd door Aleksei Makarov, InnoDoks uit Middelbeers is de uitgever. Het boek is gebonden met harde kaft en kost 14,95 euro.

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive U-V, Art & Literature News, Ven, Jace van de

Carina van der Walt

Bioskets | Biography

Carina van der Walt is in Welkom gebore. In Nederland word sy reëlmatig daaraan herinner hoe spesiaal dit is om op só ’n plek ’n mens se lewe te kon begin. Haar kinderjare het sy redelik sorgvry deurgebring.

Daarna volg wydverspreid oor baie jare ’n akademiese opleiding aan die PUK, later die NWU en ook die Katolieke Universiteit van Brabant in Tilburg. Sy cum in 2004 haar M in ’n vergelykende studie tussen Afrikaanse en Nederlandse poësie. Tussendeur trou sy, word ma, hou skool, gee klas aan die NWU, word weduwee met twee klein kindertjies, en reël wyd en syd vier jaar lank ’n skrywerskompetisie vir die ATKV. SAVN-kongresreëlings in Potchefstroom (2004) en simposium-organiseerder in Tilburg (2009) pas binne haar portefeulje. Sy ontmoet Geno Spoormans tydens navorsingstyd in Nederland. Drie jaar later trou hulle. Carina verplaas begin 2007 haar lewe na Nederland. Hier skryf sy voltyds.

Die appel van haar oog is 25 en woon in Durban. Sy het hom so lief soos die sand en die branders van die see … met die intensiteit van elke volmaakte sewende golf.

Haar hart se punt is ’n 21-jarige student in Stellenbosch. Sy het haar so lief soos die sterre in die Melkweg … en die Suiderkruis wat rigting gee.

Daarom bly haar bande met Suid-Afrika sterk. Die invloed en blootstelling van verskillende Europese lande, kulture, tale en denkwyses is ’n boks Quality Street. Sy deel dit graag. Dit maak haar ’n beter Suid-Afrikaner en wêreldburger.

carina van der walt

Vrouestemme oorheers digterswêreld

Carina van der Walt

2013-02-05

Nasionale Gedigtedag 2013 het vir ’n dubbele verrassing gesorg. Op Donderdagaand 31 Januarie is Anne Vegter (54) aangekondig as die opvolger van Ramsey Nasr. Sy is die eerste vroulike Dichter des Vaderlands. Die vorige aand is Ester Naomi Perquin (33) aangekondig as die wenner van die VSB-poësieprys met haar digbundel Celinspecties. Albei hierdie stemme kom uit Rotterdam. ’n Week vroeër is die Constantijn Huygens-prys (’n oeuvreprys) toegeken aan Joke van Leeuwen. Dis nou die tyd vir die erkenning van uitsonderlike vrouestemme.

Vegter was uiters verbaas toe sy deur Bas Kwakman, direkteur van Poetry International, gebel is met die vraag of sy vaderlandsdigter wil word: “Ik viel van mijn stoel. Echt. Het was surreëel.”

En saam het haar het omtrent driekwart van die Nederlandse poësiewêreld van hulle stoele afgetuimel, want die persepsie van Vegter se poësie is dat dit nogal onverstaanbaar is. Kreek Daey Ouwens, ’n kollega van Vegter, beskryf haar gedigte as rou en eroties. Fynproewerlesers ken Vegter veral deur Ongekuiste versies (1994). Dis ’n bundeltjie met erotiese kortverhale. In die inleiding van haar laaste digbundel – Eiland, berg, gletsjer (2011) – staan: “Haar poëzie is heel fysiek, alles is hier lichamelijk en aanraakbaar. … We hebben het hier over erotiek die zo sterk is dat ze overal in doordringt, zeker in haar poëzie waarin ze voortdurend tot uitbarsting komt.”

Die titelgedig, “Eiland, berg, gletsjer”,begin met op elke bladsy twee lang tweereëlige sinne:

Ook als je wakker word boven een sterfgebied en je gespt kinderen vast als gordels: laat mij

eens door een raam kijken of het daar erg is, zie je er niets van want het is een diepteoorlog.

Ook als een doelwit vanaf die grond toch naar je zwaait en je verlangt naar bleke sterren

op zo’n voorhoofdje, taxie je over het oefenveldje van je grimassen en je speelt elk karakter.

*

Ook als haar schacht krimpt en tembaarheid ontsnapt haar rode lassen, wakkert ze

vuur aan dat het stelsel doorwarmt en haar brille ontstolt tot ja! Optimisme, stokt ze.

Ook als haar XXL-geluksmaatje boven de grond komt ‘als een dode kompel’ (eerste tel ik

mijn vrouwen, daarna mijn dagen) weet ze weer de kleine methode van zijn handen.

Vegter se laaste twee bundels was albei genomineer vir die VSB-poësieprys, maar sy het dit nie gekry nie. Dit was Eiland, berg, gletsjer en Spamfighter (2007). Haar oeuvre is relatief klein, met vier digbundels versprei oor twintig jaar. Die stadsdigterskap van Rotterdam het ook nie na haar kant toe gegaan nie – iets waarop sy heimlik gehoop het en waarvoor sy bevoeg genoeg gevoel het. Iets groters het egter op haar gewag: Dichter des Vaderlands, 2013–2017.

y is (anders as haar voorganger, Ramsey Nasr) nie deur die publiek gekies vir hierdie uitsonderlike funksie nie. Sy is daarvoor gevra. Nadat sy herstel het van haar aanvanklike verbasing, was haar reaksie daarop bietjie droog: “Ik ben niet tegen positieve discriminatie. En er zijn veel vrouwelijke dichters, dus er was keuze genoeg.”

Nog verskille met Nasr is dat Vegter nie die podium so benut nie en dat sy waarskynlik nie politieke kommentaar gaan lewer op die Nederlandse samelewing nie. Laasgenoemde is iets waarvoor Nasr beide gerespekteer en gekruisig is. Ondanks die vermoede dat Vegter nie so ‘n groot podiumdigter soos Nasr sal wees nie, het sy haar vinger op die pols van nuwe ontwikkelinge. Haar voornemens vir haar tyd as vaderlandsdigter sluit onder andere gedigte op You Tube-filmpies en digterlike flashmops met minstens 500 mense op ’n slag in.

Die samestelling van die kommissie vir die benoeming van ’n nuwe vaderlandsdigter het die tipe digter weerspieël waarna hulle gesoek het: iemand wat veelsydig is. Die kommissie het uit ses lede bestaan uit die wêrelde van skrywers, televisie, koerant, politiek en poësiekritiek. Vegter ís veelsydig. Haar oeuvre bevat meer prosa as poësie, en selfs toneel. Haar eerste literêre toekenning was die Woutertje Pieterse-prys vir die kinderboek De dame en de neushoorn (1989). In haar oeuvre kry lesers dus die vreemde kombinasie van kinderboeke en volwasse erotiek. Maar hierdie oënskynlik onversoenbare aspekte verbind sy moeiteloos as beweer word dat haar beste werk uit ’n kinderlike blik ontstaan, met: “De gewetensvolle, volwassen blik corrigeert dat weer.”

Vegter se oeuvre het raakpunte met dié van die sestigjarige Joke van Leeuwen. Albei hierdie digteresse skryf ernstige, volwasse werk – maar óók werk vir kinders. Volgens die jurie van die Constantijn Huygens-prys het Van Leeuwen haar nog altyd verset ten die tweedeling tussen kinderliteratuur en volwasse literatuur. Haar werk verbreek telkens hierdie grens deur met ’n kindperspektief te skryf oor ernstige sake soos byvoorbeeld geweld, mag en rassisme. Met die erkenning van twee sulke prominente digteresse se veelsydige oeuvres en die sigbare ooreenkomste daarin, kan die noukeurige leser egter vra of alle vrouestemme dan uit ’n kinderperspektief moet kan skryf.

Beide Van Leeuwen en Vegter hou van visuele aspekte by hulle poësie. Eiland, berg, gletsjer is ook deur Vegter geïllustreer met krabbelrige sketsies. Van Leeuwen se agtergrond as grafiese ontwerper het veral gedurende haar tydperk as stadsdigter van Antwerpen konkreet in die stad tot uiting gekom.

Die jurie van die Constantijn Huygens-prys het hulle keuse vir Van Leeuwen onder andere so verwoord:

Haar werk is onconventioneel en verrassend speels. Ze schrijft over innemende wezens, kinderen en volwassenen die hun eigen eigenzinnige gang proberen te gaan. Tedere anarchie is haar handelsmerk. Ze houdt van taal en elk boek getuigt van de tover van 26 letters. Vooral in haar werk voor kinderen, maar ook in dat voor volwassenen gaan woord en beeld een vrolijk gevecht aan, of vallen in elkaars armen.

Van Leeuwen is al ’n bekende in Suid-Afrika – net soos Luuk Gruwes en Menno Wigman, wat albei genomineer was vir die VSB-poësieprys. Hulle genomineerde bundels was onderskeidelik Wijvenheide (Gruwes) en Mijn naam is Legioen (Wigman). Dit was swaar sluk vir Wigman toe Perquin met Celinspecties (2012) die prys voor sy neus weggeraap het, want hy was verreweg as die gunsteling aangekondig in die pers. Ron Rijghard het byvoorbeeld sy artikel in die NRC-Handelsblad op 25 Januarie begin met: “De VSB-Poëzieprijs 2013 moet gaan naar Mijn naam is Legioen van Menno Wigman.” Die oproep waarmee Rijghard sy artikel ook geëindig het, het egter op dowe ore geval. Die jurie roem “de verraderlijk luchtige toon en de onvoorspelbare wendingen” in Perquin se bundel.

Die ander genomineerdes was die 74-jarige HH ter Balkt en die 88-jarige Sybren Polet. Na die aankondiging het die saal gesug. Perquin se bundel is goed, maar sy is nog so jonk. Sy kan dit altyd volgende jaar of die jaar daarna wen. Kon hulle nie maar die ouer manne soos Ter Balkt (wenner van die PC Hoofd-prys in 2003) ’n kans gee nie? Rijghard redeneer selfs dat HH ter Balkt se status die VSB-poësieprys se prestige weer ’n bietjie sou kon herstel, ná die “postmoderne nonpoëzie van Jan Lauwereyns” van die vorige jaar. Die kandidate van die VSB-poësieprys 2013 het een gemene deler gehad: ’n pessimistiese blik op mens en wêreld.

In ’n breër sin was die toekenning aan Perquin se bundel net so ’n verrassingselement soos by Vegter en ook soos die werklike betekenis van die einste bundel se titel. Wat is tog die verborge vermoë van poësie om lesers by Celinspecties eerstens te laat dink aan liggaam- of plantselle? Nee, dis baie blatanter. Hierdie bundel gaan oor die inspeksies in tronkselle uit ’n tyd toe Perquin ’n tronkbewaarder was. Sy is geïnteresseerd in die kwaad. Deur haar taal kry die moordenaars elkeen ’n gloed van ’n poëet. Oor haar gedigte hang ’n skadu van geweld. Celinspecties is haar derde digbundel.

Gesprek

Op straat zegt een man in zijn telefoon nee zegt niet schreeuwt

wie denk je eigenlijk, haalt adem, ziet mij staan,

wie denk je dat je bent

met je goede manieren zogenaamd die rijke vrienden van je

met je vol geplande week je goede baan

zijn stem breekt het toestel open,

die vrouw rolt ineens over straat, half aangekleed, mascara

uitgelopen, krabbelt overeind, staat verbaasd

en hij begint weer opnieuw

wie denk je dat je bent en kijkt naar mij terwijl hij slaat,

blijft kijken tot ik roep dat is genoeg stop ze ligt

al opgerold ze doet je niks man stop

maar hij is nog niet uitgepraat en kijkt naar mij en vraagt

wie denk je blijft maar doorgaan in zijn handpalm

woorden maken, dat je bent

houdt niet meer op.

(Uit Celinspecties, 2012)

Met haar gedigte se donker kante en suggesties van gevaar kan Perquin se poësie as hard ervaar word, maar haar seggingskrag sorg vir balans. Sy skryf uit ’n volwasse perspektief. Daardeur onderskei die jonge Perquin haar van beide Vegter en Van Leeuwen. En daarom moet sy fyn dopgehou word.

# Lees Anne Vegter se gedig, Gebed voor iedereen

fleursdumal.nl magazine for art & literature

More in: Archive W-X, Carina van der Walt, Walt, Carina van der

Esther Porcelijn

Argwaan

Ben jij nog wel mijn leider?

Ben jij nog wel de baas van alles?

Ben jij nog wel mijn sokpop?

Ben jij nog wel de klootzak?

Kook jij nog wel spinazie en eitjes voor mij?

Stop jij mij nog wel in?

Zing jij nog wel een liedje voor mij?

Knabbel je nog wel aan mijn vel?

Kus je nog wel op mijn nare gedachten?

Was je nog wel mijn hoofd en mijn haar?

Wil je mij nog wel soms een dag zien?

Wil je nog wel mijn regels verzinnen?

Ga je nog wel aan de afwas beginnen?

Snij je nog wel de uien voor de haring?

Bepaal je nog wel hoe het gaat?

Wil jij nog wel mij bekijken?

Ben ik nog wel je sokpop?

Lig je vannacht weer naast mij?

Esther Porcelijn gedicht

uit de nieuwe bundel: De keren dat ik verwaai

De keren dat ik verwaai is verkrijgbaar of te bestellen

via de reguliere boekhandel of

via uitgeverij teleXpress – www.telexpress.nl

ISBN/EAN: 978-90-76937-44-1

Prijs: 15 euro

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive O-P, Porcelijn, Esther

U I T N O D I G I N G

t e l e X p r e s s

www.telexpress.nl

dubbelpresentatie teleXpress op 26 september 2013:

De keren dat ik verwaai, debuutbundel Esther Porcelijn en

De Hel van Ruud Welten

in theater DE NWE Vorst, aanvang 20.30 uur

Op 26 september a.s. lanceert uitgeverij teleXpress in theater De NWE Vorst in Tilburg een tweetal nieuwe, bijzondere publicaties. Het betreft De keren dat ik verwaai, de debuutbundel van Esther Porcelijn, stadsdichter van Tilburg 2011-2013. Daarnaast, ruim een maand voor de honderdste geboortedag van Albert Camus, De Hel, een toneelstuk over Sartre, Camus en (hedendaags) terrorisme van filosoof en publicist Ruud Welten.

Tijdens de presentatie zal Esther Porcelijn – als altijd op pakkende wijze – voordragen uit haar bundel. Daarnaast vormen gelezen tekstfragmenten door Esther Porcelijn (naast dichter ook acteur en filosofiestudent) en filosoof en Sartrekenner Paul Cobben aanleiding voor een discussie tussen Ruud Welten, Hans Achterhuis, filosoof en auteur van o.a. Met alle geweld, theaterregisseur Tarkan Köroğlu en de overige sprekers. Moderator is Leon Heuts, redacteur van Filosofie Magazine.

In De keren dat ik verwaai beziet de voormalige stadsdichter van Tilburg, Esther Porcelijn, de stad en haar bewoners met de scherpe, maar tegelijkertijd zachtmoedige blik van de buitenstaander. De intermenselijke relaties in al hun verschijningsvormen worden door haar op associatieve, soms dromerig-poëtische dan weer beschouwelijke wijze neergezet, zij het telkens gelardeerd met de nodige ironie en humor.

De naoorlogse controverse tussen Sartre en Camus blijkt ook in de 21ste eeuw nog niets aan actualiteit te hebben ingeboet. Door het gedachtegoed van Sartre en Camus te confronteren met dat van een jonge islamitische terroriste, zet Ruud Welten de zaak op scherp, houdt hij ethische en existentiële kwesties tegen een hedendaags licht en zet hij de lezer aan het denken. Op heldere en tegelijkertijd speelse wijze worden deze kwesties de 26ste ten tonele gevoerd.

Behalve het toneelstuk bevat De Hel bijdragen van Sartre, Camus en een interview met toneelregisseur Tarkan Köroğlu.

Ruud Welten (1962) is filosoof. Hij is als universitair docent werkzaam aan de Universiteit van Tilburg en als lector bij de hogeschool Saxion te Deventer. Van zijn hand verschenen tal van publicatie over o.m. Sartre. Onlangs verscheen eveneens van zijn hand: Het ware leven is elders. Filosofie van het toerisme.

Esther Eva Porcelijn (1985) is toneelspeler, theatermaker en dichter. Na een paar jaar Toneelacademie in Maastricht ging ze naar Tilburg om er aan de universiteit filosofie te gaan studeren. Al snel werd ze tot stadsdichter van Tilburg verkozen (2011 – 2013). Sindsdien treedt ze in heel Nederland op met haar poëzie, korte verhalen, columns en theatervoorstellingen.

Porcelijns gedichten en prozastukken zijn verschenen in Brabant Literair, Strak en Hollands Maandblad. In 2013 won ze de Hollands Maandblad Aanmoedigingsbeurs 2012-2013 voor haar poëzie.

agendagegevens

boekpresentatie debuutbundel Esther Porcelijn en toneelstuk Ruud Welten, presentatie Leon Heuts (Filosofie Magazine), m.m.v. filosoof Paul Cobben, theaterregisseur Tarkan Köroğlu en als speciale gast filosoof en publicist Hans Achterhuis

datum: 26 september

aanvang : 20.30 uur, inloop vanaf 20.00 uur

locatie: De NWE Vorst, Willem II straat 48, 5038 BD Tilburg

entree : 5 euro

kaarten bestellen: www.denwevorst.nl

De keren dat ik verwaai is verkrijgbaar of te bestellen via de reguliere boekhandel of via uitgeverij teleXpress – www.telespress.nl – ISBN/EAN: 978-90-76937-44-1 – Prijs: 15 euro

De Hel/ l’Enfer is verkrijgbaar of te bestellen via de reguliere boekhandel of via uitgeverij teleXpress – www.telexpress.nl – ISBN/EAN:978-90-76937-43-4 – Leverbaar: 27 september 2013 – Prijs: 15 euro

fleursdumal.nl magazine for art & literature

More in: Art & Literature News, City Poets / Stadsdichters, Ivo van Leeuwen, Porcelijn, Esther

Carina van der Walt

Volledig volmaakte oneetbare kersies

(vir Gerrit Kouwenaar)

hand aan hand dwaal ons

deur galery na galery

langs die Hartbeespoortdam

buite stuifreën dit grys

en silwer oumansbaard

nes destyds in Parys

’n local se gedempte kersies

kitscherig onder sand en skulp

vasgeskilder ontlok opeens

skerpsuur die geur van

’n knalrooi kersietert

in die Champs-Élysées

donkersoet die likeur van

’n kersenbonbon

gevoer met die mond

Mon Cheri

Uit: Nuwe Stemme 5, p.80

Carina van der Walt poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive W-X, Carina van der Walt, Walt, Carina van der

.jpg)

Delmira Agustini

(1886-1914)

Al Claro De Luna

La luna es pálida y triste, la luna es exangüe y yerta.

La media luna figúraseme un suave perfil de muerta…

Yo que prefiero a la insigne palidez encarecida

De todas las perlas árabes, la rosa recién abierta,

En un rincón del terruño con el color de la vida,

Adoro esa luna pálida, adoro esa faz de muerta!

Y en el altar de las noches, como una flor encendida

Y ebria de extraños perfumes, mi alma la inciensa rendida.

Yo sé de labios marchitos en la blasfemia y el vino,

Que besan tras de la orgia sus huellas en el camino;

Locos que mueren besando su imagen en lagos yertos…

Porque ella es luz de inocencia, porque a esa luz misteriosa

Alumbran las cosas blancas, se ponen blancas las cosas,

Y hasta las almas más negras toman clarores inciertos!

Delmira Augustini poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Agustini, Delmira, Archive A-B

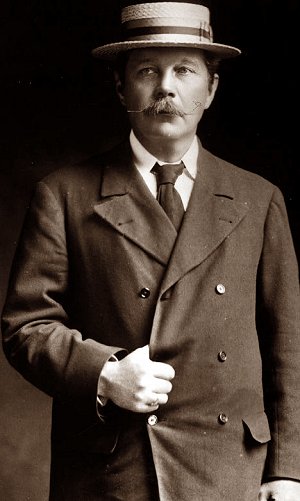

Arthur Conan Doyle

(1859-1930)

By the North Sea

Her cheek was wet with North Sea spray,

We walked where tide and shingle

meet;

The long waves rolled from far away

To purr in ripples at our feet.

And as we walked it seemed to me

That three old friends had met that

day,

The old, old sky, the old, old sea,

And love, which is as old as they.

Out seaward hung the brooding mist

We saw it rolling, fold on fold,

And marked the great Sun alchemist

Turn all its leaden edge to gold,

Look well, look well, oh lady mine,

The gray below, the gold above,

For so the grayest life may shine

All golden in the light of love.

Arthur Conan Doyle poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive C-D, Arthur Conan Doyle, Doyle, Arthur Conan

MARTIN BEVERSLUIS

T.

Twee torenspitsen tanken twaalf

tellen tegenlicht tevens treitert

toeval talent telkens tegenslagen

tenenkrommend toen totems

tempels tanend talmend toezagen

trots toestonden tof tekortschoten

tekens tegenwoordig tampeloeres

tetanus teef toverstafjes trainden

tafels tegen tranen tegenstrevers

toonden taken tuitten totnogtoe

toeten toverden tepels troon

toekenning tomaten tijd totaal

tenietgedaan toekomsten toch

toegestaan tilburg tilt tot top.

Martin Beversluis poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Beversluis, Martin

Elizabeth (Lizzie) Siddal

(1829-1862)

The Lust of the Eyes

I care not for my Lady’s soul

Though I worship before her smile;

I care not where be my Lady’s goal

When her beauty shall lose its wile.

Low sit I down at my Lady’s feet

Gazing through her wild eyes

Smiling to think how my love will fleet

When their starlike beauty dies.

I care not if my Lady pray

To our Father which is in Heaven

But for joy my heart’s quick pulses play

For to me her love is given.

Then who shall close my Lady’s eyes

And who shall fold her hands?

Will any hearken if she cries

Up to the unknown lands?

Elizabeth (Lizzie) Siddal poems

fleursdumal.nl magazine for art & literature

More in: Archive S-T, Lizzy Siddal, Siddal, Lizzy

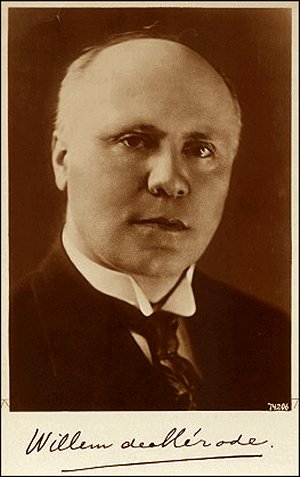

Willem de Mérode

(1887-1939)

De Dichter

Er leven velen in hem, maar zij sluimren.

Hij mag hen niet ontwekken, en hij wacht

Of geen zich wakker woelen zal, en zacht,

Een duif, tot ’t leven kringlen zal en tuimlen.

Als hij hun schaduw in de grijze nacht

Bewegen ziet, en waagt in de gezichten

Een licht te wekken en met hen te richten,

Bespeurt hij dat hun masker hem veracht.

Zij moeten zelf uit zware slaap zich breken,

Dan zullen zij door zijne lippen spreken

Met woorden ademwarm van liefde en nood.

Hij was zeer moedeloos en zeide bitter:

Bleek wordt hun slaap en ’t leven maakt mij witter.

En toen ontwaakte een in hem en werd groot.

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive M-N, Mérode, Willem de

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature