Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

Paul van Ostaijen

(1896-1928)

Zelfmoord des Zeemans

De zeeman

hij hoort de stem der Loreley

hij ziet op zijn horloge

en springt het water in

Loreley

Kom aan mijn borst

kom aan mijn borst

daar rust gij aan een lijf

dat eenzaam is een bedden van uw eenzaamheid

en eenzaam spelen uwe vingers

langs het ontwarren van lange wier

Achter de spiegel die verdrijft

de onbestendigheid der dingen

valt van uw handen het verlangen

aan mijn opalen huid verglijdend

een wezenloze droom

kom aan mijn borst

bed in mijn eenzaam’ armen

uw eenzaam lijf

Geboortehuis Paul van Ostaijen

Lange Leemstraat, Antwerpen

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Historia Belgica, Museum of Literary Treasures, Ostaijen, Paul van

Gérard de Nerval

(1808-1855)

Les Écrivains

Où fuir ? Où me cacher ? Quel déluge d’écrits,

En ce siècle falot vient infecter Paris,

En vain j’ai reculé devant le Solitaire,

Ô Dieu du mauvais goût ! Faut-il donc pour te plaire

Entasser des grands mots toujours vides de sens,

Chanter l’homme des nuits, ou l’esprit des torrents,

Mais en vain j’ai voulu faire entrer dans ma tête,

La foudre qui soupire au sein de la tempête,

Devant le Renégat j’ai pâli de frayeur ;

Et je ne sais pourquoi les esprits me font peur.

Ô grand Hugo, poète et raisonneur habile,

Viens me montrer cet art et grand et difficile,

Par lequel, le talent fait admirer aux sots,

Des vers, peut-être obscurs, mais riches de grands mots.

Ô Racine, Boileau ! vous n’étiez pas poètes,

Déposez les lauriers qui parèrent vos têtes,

Laissez à nos auteurs cet encens mérité,

Qui n’enivra jamais la médiocrité ;

Que vos vers relégués avec ceux de Virgile,

Fassent encore l’ennui d’un Public imbécile,

lis sont plats, peu sonnants, et souvent ennuyeux,

C’était peut-être assez pour nos tristes ayeux,

Esprits lourds et bornés, sans goût et sans usage,

Mais tout se perfectionne avec le temps et l’âge.

C’est comme vous parlez, ô sublimes auteurs,

Il ne faut pas, dit-on, disputer des couleurs,

Cependant repoussant le style Romantique

J’ose encor, malgré vous, admirer le classique

Je suis original, je le sais, j’en conviens,

Mais vous du Romantisme, ô glorieux soutiens,

Allez dans quelques clubs ou dans l’Académie

Lire les beaux produits de votre lourd génie,

Sans doute ce jour-là vous serez mis à neuf,

Paré d’un long jabot et d’un habit d’Elbeuf

Vous ferez retentir dans l’illustre assemblée,

Les sons lourds et plaintifs d’une muse ampoulée.

Quoi, misérable auteur que vieillit le travail,

Voilà donc le motif de tout cet attirail,

Surnuméraire obscur du Temple de la gloire,

Tu cherches les bravos d’un nombreux auditoire.

Eh quoi, tu ne crains pas que quelques longs sifflets,

Remplissent le salon de leurs sons indiscrets

Couvrant ta lourde voix au sortir de l’exorde,

En te faisant crier, grâce, Miséricorde !

Et c’était pour l’appât des applaudissements ?

Que dans ton cabinet tu séchas si longtemps ;

Voilà donc le motif de ta longue espérance

Quoi tout fut pour la gloire, et rien pour la science ?

Le savoir n’aurait donc aucun charme puissant

S’il n’était pas suivi d’un triomphe brillant,

Et tu lui préféras une vaine fumée,

Qui n’est pas la solide et bonne renommée

Sans compter direz-vous combien il est flatteur

D’entendre murmurer : C’est lui, ce grand auteur,

D’entendre le publie en citer des passages,

Et même après la mort admirer ses ouvrages ;

Pour le défunt, dis-tu, quel triomphe éclatant,

Sans doute pour le mort c’est un grand agrément

Sa gloire embellira sa demeure dernière,

La terre qui le couvre en est bien plus légère.

Ah ! C’est trop vous moquer de nos auteurs nouveaux,

Dis-tu, lorsque vous-même avez tous leurs défauts,

Mais en vain vous voulez censurer leurs ouvrages,

Vous les verrez toujours postuler des suffrages

Vous les verrez toujours occupés tout entiers,

A tirer leurs écrits des mains des Épiciers.

Mais vous, qui paraissez faire le moraliste,

De l’état d’Apollon ennuyeux rigoriste

Que retirez-vous de vos discours moraux ?

La haine des auteurs, et l’amitié des sots.

Ô toi qui me tint lieu jusqu’ici d’auditoire

Me crois-tu donc vraiment insensible à la gloire !

Si ma Plume jamais produisait des écrits ;

Qui ravissent la palme à tous nos beaux esprits.

J’aimerais à gagner un hommage sincère,

Mais je plains ton orgueil, Écrivain téméraire

Qui crois que les bravos qu’à dîner tu reçois,

Témoignent ton mérite, et sont de bon aloi.

Et cet Auteur encor qui sur la Place invite

A son maigre dîner, un maigre Parasite

Et qui lui dit ensuite à la fin du repas,

” Amis, parlez sans fraude, et ne me flattez pas,

” Trouvez-vous mes vers bons ? Dites en conscience ”

Peut-il à votre avis dire ce qu’il en pense ?

En plein barreau Damis est traité de voleur

Il prend pour sa défense un célèbre orateur

Comment défendra-t-il une cause pareille ?

Par des mots, de grands mots, et l’on dira, Mervei11e !

Eh ! Quoi peuple ignorant, vous gardez vos bravos,

Et vos cris répétés pour encenser les sots,

Croyez-vous qu’en chantant une chanson risible,

Un Pauvre à ses malheurs me rende bien sensible

Non, à d’autres plus sots il pourra s’adresser,

Et le vrai, le vrai seul pourra m’intéresser.

(1825)

Gérard de Nerval: Les Écrivains

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive M-N, Nerval, Gérard de, Nerval, Gérard de

.jpg)

P. A. d e G é n e s t e t

(1829 – 1861)

‘T was toch de Hovenier

Zij, meenende dat het de hovenier was.

Joh. XX: 15.

’t Was toch de Hovenier, Hij, die in Jozefs gaarde

Uw schreiend oog verscheen, o droeve, teedre vrouw,

Toen niets meer dan een lijk uw schat was op deez’ aarde,

En alles wat gij zocht in groote zielerouw!

’t Was toch de Hovenier, Hij, die begon te vragen:

Wien zoekt gij? – die u straks Maria! tegenriep,

En met zijn woord het licht deed in uw ziele dagen

En in een paradijs uw woestenij herschiep!

’t Was toch de Hovenier! De knoppen gingen open,

Gereed te sterven op den akker van ’t gemoed,

De knoppen van geloof en liefde en vreugde en hope,

Bij ’t ruischen van zijn uchtendgroet.

Zij wachtten op zijn dauw, zij smachtten naar zijn zegen,

De kiemen aller deugd, de bloemen van het hart:

Zijn woord was voor haar groei de wondre lenteregen,

Zijn blik de milde zon, na winterkoude en smart!

Ze ontloken om niet weër te sterven, maar te bloeien,

o Langer dan een lente-, een schoonen zomerdag,

Om, door Zijn zorg gekweekt, in ’t diepst der ziel te groeien,

Hoe menig bloem der aard het oog verwelken zag!

’t Was toch de Hovenier! En, wie in ’s levens gaarde

Dien Man niet heeft ontmoet, Maria, zoo als gij,

Zijn ziele schreit en smacht, al bloeit de zonnige aarde,

En zoekend waart hij om in ’t lentefeestgetij.

1859

.jpg)

P.A. de Génestet gedichten

k e m p i s p o e t r y m a g a z i n e

More in: Génestet, P.A. de

.jpg)

W i l l e m K l o o s

(1859-1938)

Elk kloppen van mijn bloed is een gebed

Elk kloppen van mijn bloed is een gebed,

Wanneer ‘k de handen samen-vouwend smeke

Om één, Onkenbaar Wezen! – één, één teken

Van U, mijn God, mijn Eénge Heer, Die let

Op elke daad, gedachte of woord, o Het

Aller-aller-onkenbaarst Zijn, die ‘t weke

Bewegen mijner ziel hebt doorgekeken,

Hoe het zich-zelf in zich-zelf steeds verzet, –

O God, mijn God, Gij zijt wel gans-almachtig,

Schoon ‘k niet begrijp hoe ‘t slechte kan op de aard zijn,

Maar Gij zijt God, God-zelf, voor Wie ik, krachtig

Mens, door Uw Wil, deemoedig buig in prachtig

Vernederen mijns-zelfs in diep-vervaard zijn.

O! ‘t echte slechte nimmer kan iets waard zijn.

.jpg)

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Kloos, Willem

‘Het is geen roman, ‘t is een aanklacht!’

150 jaar Max Havelaar

Tentoonstelling rond het meesterwerk van Multatuli

woensdag 3 februari, 10:00 – zondag 16 mei 2010, 17:00 uur

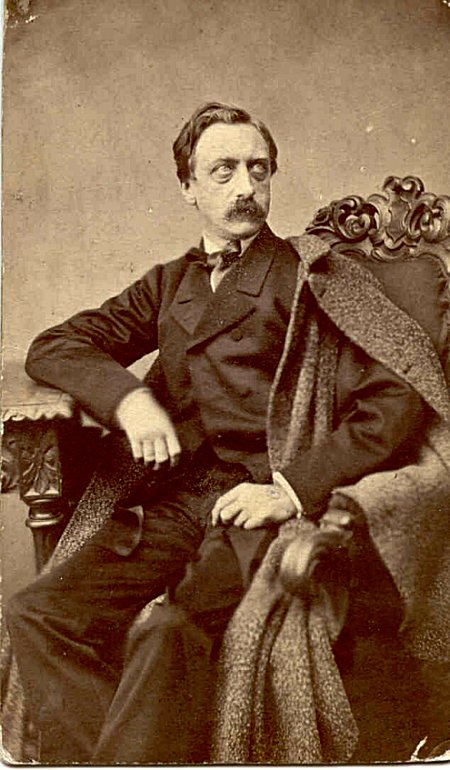

Honderdvijftig jaar geleden schreef Multatuli zijn beroemde boek Max Havelaar: een werk van uitzonderlijke literaire kwaliteit, dat bovendien een enorme maatschappelijke en politieke impact heeft gehad. Het is dan ook opgenomen in de Canon van de Nederlandse Geschiedenis. De uitgave van dit belangrijke boek wordt herdacht met de tentoonstelling ‘Het is geen roman, ‘t is een aanklacht!’ 150 jaar Max Havelaar. Deze tentoonstelling is te zien bij de Bijzondere Collecties van de Universiteit van Amsterdam, de plek waar de handschriften van Multatuli worden bewaard.

Op 15 mei 1860 verscheen bij uitgeverij De Ruyter in Amsterdam het boek dat de Nederlandse geschiedenis een andere wending zou geven: Max Havelaar of de koffij-veilingen van de Nederlandsche Handel-Maatschappij. Multatuli, pseudoniem van Eduard Douwes Dekker (1820–1887), wilde met het boek de misstanden aan de kaak stellen die hij had meegemaakt toen hij van 1838 tot 1856 als ambtenaar diende in Nederlands-Indië.

.jpg)

Tentoonstelling

In de tentoonstelling wordt het politieke, maatschappelijke en literaire belang van Max Havelaar in beeld gebracht. Centraal staat de aanklacht tegen onderdrukking, een boodschap die nog steeds actueel is. De tentoonstelling is gemaakt door de Bijzondere Collecties van de Universiteit van Amsterdam in samenwerking met het Multatuli Genootschap.

Over Max Havelaar en Multatuli wordt nog steeds veel geschreven en gesproken. De aanklacht tegen onderdrukking en strijd voor rechtvaardige en eerlijke handel (fair trade) is een boodschap die nog altijd actueel is. Het internationale keurmerk voor fair trade-producten heet in een aantal Europese landen dan ook Max Havelaar. Ook hiervoor aandacht in de tentoonstelling.

Multatuli hekelde in zijn boek de koopman en de dominee, klaagde het koloniale wanbestuur aan en rechtvaardigde de ambtenaar die wel voor de verdrukten opkwam. Na het verschijnen van Max Havelaar kon men niet meer ontkennen dat er in de kolonie veel mis was. Het boek had een sturende werking, zowel voor het ambtelijke apparaat in Nederlands-Indië als voor de koloniale politiek, en veranderde definitief het denken over het kolonialisme in Nederland.

De uitzonderlijke literaire kwaliteit van Max Havelaar is altijd geroemd. Met recht geldt Multatuli als een van de belangrijkste schrijvers uit onze literatuur. Maar het was hem niet te doen om de kunst, hij wilde vooral de publieke opinie beïnvloeden. Hoewel hij zijn boodschap verpakte als roman, was het een vlijmscherpe politieke satire.

‘Het is geen roman, ‘t is een aanklacht!’

Op 13 oktober 1859 schreef Multatuli aan zijn vrouw Tine: ‘Lieve hart, mijn boek is af, mijn boek is af! Hoe vind je dat? (…) Het zal als een donderslag in het land vallen dat beloof ik je.’ En aan tekstbezorger Jacob van Lennep, die met zijn ingrepen de angel uit het boek haalde, liet hij weten: ‘(…) het is geen roman. ‘t Is eene geschiedenis. ‘t Is eene memorie van grieven, ‘t Is eene aanklagt, ‘t Is eene sommatie!’

Max Havelaar Academie

Ter gelegenheid van 150 jaar Max Havelaar hebben de Bijzondere Collecties de Max Havelaar Academie opgericht. Zes studenten krijgen de gelegenheid om als stage, tussen januari en mei 2010, een ‘nieuwe Max Havelaar’ te maken. De stageopdracht luidt: ‘Verplaats de thema’s uit de Max Havelaar naar de 21ste eeuw en maak nieuwe verhalen, met moderne (geschreven en audiovisuele) media, die eenzelfde effect willen hebben als het oorspronkelijke boek heeft gehad.’ Een serie publiekslezingen/’masterclasses’ over de actuele betekenis van het boek is onderdeel van de Max Havelaar Academie.

Het is geen roman, ‘t is een aanklacht! 150 jaar Max Havelaar

3 februari t/m 16 mei 2010

Bijzondere Collecties van de Universiteit van Amsterdam

Oude Turfmarkt 129 (Rokin) – 1012 GC Amsterdam

open di–vrij 10–17 uur, za–zo 13–17 uur

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: DICTIONARY OF IDEAS, Multatuli, Multatuli, Multatuli

.jpg)

Willem Bilderdijk

(1756-1831)

D e K r a n k e

Waar, waarom, gy, die zonder pennen,

Onzichtbaar wandelt door de lucht,

Die ’t distelscheutjen buigt, en lispelt door de dennen,

Wiens adem piept in ’t riet, en in den rotsgalm zucht; —

Gy, koelten, fladdrend door de dalen,

Waar, waarom stelt ge ’t luistrend oor

Dat naar uw zuizen haakt, te loor?

Ik hoor geen golfgebruisch van ’t strandgebergt’ herhalen!

Ik hoor geen harpmuzyk dat door de rotsen klinkt!

Geen zachte vogelstem, die ’t lied der liefde zingt.

Alleen de donder der kartouwen,

Of ’t hol alarmgebrom der trom,

Genaakt mijn ziel door ’t oor. — Natuur vertoont zich stom,

En staat me, als gants vervreemd, stilzwijgende aan te schouwen.

Mijn hart begroet haar, maar geen stem, die me andwoord biedt.

Helaas! een half heelal ging voor mijn ziel te niet!

En gy, ô vonklende luister

Der schepping: wonderstof van ’t zevenkleurig licht!

Waar weekt gy? — Heldre Zon, hoe schijnt uw glans zoo duister?

Zoo weemlend voor mijn zwak en uitgedoofd gezicht?

Ach, welk een rouwfloers dekt mijne oogen,

En heeft me in ’t lichtgenot de helft der ziel onttogen,

Ja, d’alverkwikbren straal ten foltertuig gemaakt!

Mijne oogen! leert u-zelf beweenen!

’t Is nacht, ’t is eindloos nacht; ’t Heelal slaapt roerloos in!

De lekkerny van ’t hart, de schoonheid, is verdwenen!

De levens levenslust is henen,

Met al wat ik in ’t leven mijn.

ô Gy, geliefde van mijn harte,

Wat ware ik zonder u in dees afgrijsbre weên!

Gy, trouwe lenigster der smarte,

Gy zijt me een oog en oor — gy, ’t gansch Heelal alleen.

Neen, ’k zoek geen’ heul in ijdle klachten

Die ’t leed bedriegen, niet verzachten,

’k Vind in uw’ schoot alleen vergoeding voor ’t gemis.

Kom tot my! in uw’ arm omvangen,

Geketend aan uw’ hals te hangen,

Zie daar wat me in mijn leed des aardrijks hemel is!

ô Kom, en laat my van uw lippen

De tonen, die gy kweelt, indrinken met den mond!

Laat ze onvermengd uit d’uw’ in mijnen boezem glippen!

Hun toverende kracht maakt hart en ziel gezond.

ô Roep den kranke, zat van dagen,

En zinkende onder ’t wicht der plagen,

Het leven met den geest (gy kunt het daar gy zingt,

En ziels- en lichaamspijn in zachte kluisters dwingt)

In de aadren, in het hart, in de uitgedorde spieren,

Te rug! — Gy kunt het, ja, mijn boezem voelt de kracht

Die in uw’ harptoon dreunt, en ingewand en nieren

Door tokkelt met een’ gloed, die alle wee verzacht.

Kom tot my, laat ons samen zingen!

Stem gy de ontspannen snaar, en ondersteun mijn’ toon!

Verrukkend zij ’t akkoord der reine Hemelingen,

Dat van ons beider hart is even hemelschoon.

Kom, zingen wy, de ondenkbre weelde,

Die ’t hart in ’t loutrend vuur van de Echte vlam geniet!

Verheffen we ons tot Hem, die ons van ’t heil bedeelde,

Dat ruischende om zijn’ Throon in volle stroomen vliet!

Dat heil, dat vloeiende uit Hem-zelven,

De harten samensmelt in d’ongeschapen’ gloed,

Die boven lucht en stargewelven,

Zijne Englen met de kracht van zijn nabyheid voedt!

Kom, zingen we, ô mijn eenig leven,

Den wellust onzer sponde, en ’t hoogstgeschatte goed!

Wie kan ze als wy, den toon, het voorwerp waardig, geven!

Wie heeft ze als wy gesmaakt in heur volkomen zoet!

Maar ach! wat rept mijn mond van zang, van vreugdezangen,

Daar ’t lichaam meer en meer doorpriemd wordt van de smart,

Mijn toegeschroefde borst zich tot de dood voelt prangen,

En ’t bloed een zee vertoont, die opbruischt in het hart.

Van hier, van hier de zang! en gy, ô Dichtvermogen,

By matig leed zoo zoet, nu, krachtloos, nu tot leed!

Mijn mat, mijn zuizlend hoofd voelt zich naar ’t graf gebogen,

En ’k hijge naar de rust, die van geen storing weet.

Gelukkig, die in ’t stof het eind vindt van zijn plagen!

Mijn ziel is afgemat en wars van ’t gansch Heelal.

Eene andere uchtendstond moet eenmaal voor my dagen,

Die door geen Aardsch verdriet beneveld wezen zal.

Vaarwel, mijn dierbre Gâ! omhels de lieve looten,

Die God in de Aardsche ramp ons toestond tot een troost:

Ik ga, maar de Almacht blijft de Vader van ons kroost,

En zal de onnoozelheid der onschuld niet verstooten.

Vaarwel, bedroef u niet. Wat is, wat was my de aard?

Wat waare ’t, zoo my God nog leven wou vergunnen?

Hoe zoudt gy ’t voor my wenschen kunnen,

Met zoo veel jammeren bezwaard!

Wat gaf me een wareld vol van woeling,

Geruisch, gekrijsch, door één krioeling

Van valschen glans en ijdlen praal,

Van angst, en droefheid, en ellende,

En niets dan eindelooze kwaal:

Waar de onoptelbre jammerbende

Der ziekten eeuwig spookt en ’t leven ondermijnt : —

Waar ’t erfdeel van den mensch bestaat in eindloos zuchten,

En ’t geen tot troost verscheen der knellende ongenuchten,

In enkel foltering verdwijnt! —

Neen, sterven wy! die God zal ons weêrom vereenen,

Die eenmaal ons verknocht tot dees ontzetbre stond.

Vaarwel! nog eens Vaarwel! Laat af om my te weenen,

Ik sterf in Goëls naam en ’t heilig Zoenverbond.

1803

By den aanvang mijner kranke,

die my dezelfden dag van

alle kennis beroofde

.jpg)

Willem Bilderdijk gedichten

k e m p i s po e t r y m a g a z i n e

More in: Bilderdijk, Willem

.jpg)

James Joyce

(1882-1941)

A Little Cloud

Eight years before he had seen his friend off at the North Wall and wished him godspeed. Gallaher had got on. You could tell that at once by his travelled air, his well-cut tweed suit, and fearless accent. Few fellows had talents like his and fewer still could remain unspoiled by such success. Gallaher’s heart was in the right place and he had deserved to win. It was something to have a friend like that.

Little Chandler’s thoughts ever since lunch-time had been of his meeting with Gallaher, of Gallaher’s invitation and of the great city London where Gallaher lived. He was called Little Chandler because, though he was but slightly under the average stature, he gave one the idea of being a little man. His hands were white and small, his frame was fragile, his voice was quiet and his manners were refined. He took the greatest care of his fair silken hair and moustache and used perfume discreetly on his handkerchief. The half-moons of his nails were perfect and when he smiled you caught a glimpse of a row of childish white teeth.

As he sat at his desk in the King’s Inns he thought what changes those eight years had brought. The friend whom he had known under a shabby and necessitous guise had become a brilliant figure on the London Press. He turned often from his tiresome writing to gaze out of the office window. The glow of a late autumn sunset covered the grass plots and walks. It cast a shower of kindly golden dust on the untidy nurses and decrepit old men who drowsed on the benches; it flickered upon all the moving figures, on the children who ran screaming along the gravel paths and on everyone who passed through the gardens. He watched the scene and thought of life; and (as always happened when he thought of life) he became sad. A gentle melancholy took possession of him. He felt how useless it was to struggle against fortune, this being the burden of wisdom which the ages had bequeathed to him.

He remembered the books of poetry upon his shelves at home. He had bought them in his bachelor days and many an evening, as he sat in the little room off the hall, he had been tempted to take one down from the bookshelf and read out something to his wife. But shyness had always held him back; and so the books had remained on their shelves. At times he repeated lines to himself and this consoled him.

When his hour had struck he stood up and took leave of his desk and of his fellow-clerks punctiliously. He emerged from under the feudal arch of the King’s Inns, a neat modest figure, and walked swiftly down Henrietta Street. The golden sunset was waning and the air had grown sharp. A horde of grimy children populated the street. They stood or ran in the roadway or crawled up the steps before the gaping doors or squatted like mice upon the thresholds. Little Chandler gave them no thought. He picked his way deftly through all that minute vermin-like life and under the shadow of the gaunt spectral mansions in which the old nobility of Dublin had roystered. No memory of the past touched him, for his mind was full of a present joy.

He had never been in Corless’s but he knew the value of the name. He knew that people went there after the theatre to eat oysters and drink liqueurs; and he had heard that the waiters there spoke French and German. Walking swiftly by at night he had seen cabs drawn up before the door and richly dressed ladies, escorted by cavaliers, alight and enter quickly. They wore noisy dresses and many wraps. Their faces were powdered and they caught up their dresses, when they touched earth, like alarmed Atalantas. He had always passed without turning his head to look. It was his habit to walk swiftly in the street even by day and whenever he found himself in the city late at night he hurried on his way apprehensively and excitedly. Sometimes, however, he courted the causes of his fear. He chose the darkest and narrowest streets and, as he walked boldly forward, the silence that was spread about his footsteps troubled him, the wandering, silent figures troubled him; and at times a sound of low fugitive laughter made him tremble like a leaf.

He turned to the right towards Capel Street. Ignatius Gallaher on the London Press! Who would have thought it possible eight years before? Still, now that he reviewed the past, Little Chandler could remember many signs of future greatness in his friend. People used to say that Ignatius Gallaher was wild Of course, he did mix with a rakish set of fellows at that time. drank freely and borrowed money on all sides. In the end he had got mixed up in some shady affair, some money transaction: at least, that was one version of his flight. But nobody denied him talent. There was always a certain . . . something in Ignatius Gallaher that impressed you in spite of yourself. Even when he was out at elbows and at his wits’ end for money he kept up a bold face. Little Chandler remembered (and the remembrance brought a slight flush of pride to his cheek) one of Ignatius Gallaher’s sayings when he was in a tight corner:

“Half time now, boys,” he used to say light-heartedly. “Where’s my considering cap?”

That was Ignatius Gallaher all out; and, damn it, you couldn’t but admire him for it.

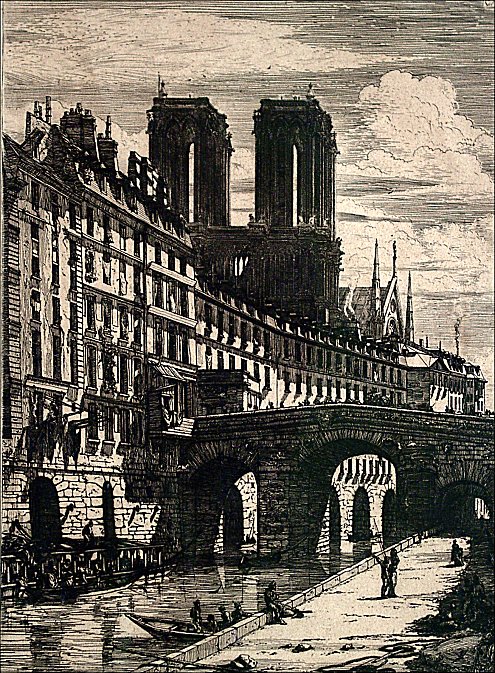

Little Chandler quickened his pace. For the first time in his life he felt himself superior to the people he passed. For the first time his soul revolted against the dull inelegance of Capel Street. There was no doubt about it: if you wanted to succeed you had to go away. You could do nothing in Dublin. As he crossed Grattan Bridge he looked down the river towards the lower quays and pitied the poor stunted houses. They seemed to him a band of tramps, huddled together along the riverbanks, their old coats covered with dust and soot, stupefied by the panorama of sunset and waiting for the first chill of night bid them arise, shake themselves and begone. He wondered whether he could write a poem to express his idea. Perhaps Gallaher might be able to get it into some London paper for him. Could he write something original? He was not sure what idea he wished to express but the thought that a poetic moment had touched him took life within him like an infant hope. He stepped onward bravely.

Every step brought him nearer to London, farther from his own sober inartistic life. A light began to tremble on the horizon of his mind. He was not so old, thirty-two. His temperament might be said to be just at the point of maturity. There were so many different moods and impressions that he wished to express in verse. He felt them within him. He tried weigh his soul to see if it was a poet’s soul. Melancholy was the dominant note of his temperament, he thought, but it was a melancholy tempered by recurrences of faith and resignation and simple joy. If he could give expression to it in a book of poems perhaps men would listen. He would never be popular: he saw that. He could not sway the crowd but he might appeal to a little circle of kindred minds. The English critics, perhaps, would recognise him as one of the Celtic school by reason of the melancholy tone of his poems; besides that, he would put in allusions. He began to invent sentences and phrases from the notice which his book would get. “Mr. Chandler has the gift of easy and graceful verse.” . . . “wistful sadness pervades these poems.” . . . “The Celtic note.” It was a pity his name was not more Irish-looking. Perhaps it would be better to insert his mother’s name before the surname: Thomas Malone Chandler, or better still: T. Malone Chandler. He would speak to Gallaher about it.

He pursued his revery so ardently that he passed his street and had to turn back. As he came near Corless’s his former agitation began to overmaster him and he halted before the door in indecision. Finally he opened the door and entered.

The light and noise of the bar held him at the doorways for a few moments. He looked about him, but his sight was confused by the shining of many red and green wine-glasses The bar seemed to him to be full of people and he felt that the people were observing him curiously. He glanced quickly to right and left (frowning slightly to make his errand appear serious), but when his sight cleared a little he saw that nobody had turned to look at him: and there, sure enough, was Ignatius Gallaher leaning with his back against the counter and his feet planted far apart.

“Hallo, Tommy, old hero, here you are! What is it to be? What will you have? I’m taking whisky: better stuff than we get across the water. Soda? Lithia? No mineral? I’m the same Spoils the flavour. . . . Here, garçon, bring us two halves of malt whisky, like a good fellow. . . . Well, and how have you been pulling along since I saw you last? Dear God, how old we’re getting! Do you see any signs of aging in me, eh, what? A little grey and thin on the top, what?”

Ignatius Gallaher took off his hat and displayed a large closely cropped head. His face was heavy, pale and cleanshaven. His eyes, which were of bluish slate-colour, relieved his unhealthy pallor and shone out plainly above the vivid orange tie he wore. Between these rival features the lips appeared very long and shapeless and colourless. He bent his head and felt with two sympathetic fingers the thin hair at the crown. Little Chandler shook his head as a denial. Ignatius Galaher put on his hat again.

“It pulls you down,” be said, “Press life. Always hurry and scurry, looking for copy and sometimes not finding it: and then, always to have something new in your stuff. Damn proofs and printers, I say, for a few days. I’m deuced glad, I can tell you, to get back to the old country. Does a fellow good, a bit of a holiday. I feel a ton better since I landed again in dear dirty Dublin. . . . Here you are, Tommy. Water? Say when.”

Little Chandler allowed his whisky to be very much diluted.

“You don’t know what’s good for you, my boy,” said Ignatius Gallaher. “I drink mine neat.”

“I drink very little as a rule,” said Little Chandler modestly. “An odd half-one or so when I meet any of the old crowd: that’s all.”

“Ah well,” said Ignatius Gallaher, cheerfully, “here’s to us and to old times and old acquaintance.”

They clinked glasses and drank the toast.

“I met some of the old gang today,” said Ignatius Gallaher. “O’Hara seems to be in a bad way. What’s he doing?”

“Nothing,” said Little Chandler. “He’s gone to the dogs.”

“But Hogan has a good sit, hasn’t he?”

“Yes; he’s in the Land Commission.”

“I met him one night in London and he seemed to be very flush. . . . Poor O’Hara! Boose, I suppose?”

“Other things, too,” said Little Chandler shortly.

Ignatius Gallaher laughed.

“Tommy,” he said, “I see you haven’t changed an atom. You’re the very same serious person that used to lecture me on Sunday mornings when I had a sore head and a fur on my tongue. You’d want to knock about a bit in the world. Have you never been anywhere even for a trip?”

“I’ve been to the Isle of Man,” said Little Chandler.

Ignatius Gallaher laughed.

“The Isle of Man!” he said. “Go to London or Paris: Paris, for choice. That’d do you good.”

“Have you seen Paris?”

“I should think I have! I’ve knocked about there a little.”

“And is it really so beautiful as they say?” asked Little Chandler.

He sipped a little of his drink while Ignatius Gallaher finished his boldly.

“Beautiful?” said Ignatius Gallaher, pausing on the word and on the flavour of his drink. “It’s not so beautiful, you know. Of course, it is beautiful. . . . But it’s the life of Paris; that’s the thing. Ah, there’s no city like Paris for gaiety, movement, excitement. . . . ”

Little Chandler finished his whisky and, after some trouble, succeeded in catching the barman’s eye. He ordered the same again.

“I’ve been to the Moulin Rouge,” Ignatius Gallaher continued when the barman had removed their glasses, “and I’ve been to all the Bohemian cafes. Hot stuff! Not for a pious chap like you, Tommy.”

Little Chandler said nothing until the barman returned with two glasses: then he touched his friend’s glass lightly and reciprocated the former toast. He was beginning to feel somewhat disillusioned. Gallaher’s accent and way of expressing himself did not please him. There was something vulgar in his friend which he had not observed before. But perhaps it was only the result of living in London amid the bustle and competition of the Press. The old personal charm was still there under this new gaudy manner. And, after all, Gallaher had lived, he had seen the world. Little Chandler looked at his friend enviously.

“Everything in Paris is gay,” said Ignatius Gallaher. “They believe in enjoying life, and don’t you think they’re right? If you want to enjoy yourself properly you must go to Paris. And, mind you, they’ve a great feeling for the Irish there. When they heard I was from Ireland they were ready to eat me, man.”

Little Chandler took four or five sips from his glass.

“Tell me,” he said, “is it true that Paris is so . . . immoral as they say?”

Ignatius Gallaher made a catholic gesture with his right arm.

“Every place is immoral,” he said. “Of course you do find spicy bits in Paris. Go to one of the students’ balls, for instance. That’s lively, if you like, when the cocottes begin to let themselves loose. You know what they are, I suppose?”

“I’ve heard of them,” said Little Chandler.

Ignatius Gallaher drank off his whisky and shook his had.

“Ah,” he said, “you may say what you like. There’s no woman like the Parisienne, for style, for go.”

“Then it is an immoral city,” said Little Chandler, with timid insistence, “I mean, compared with London or Dublin?”

“London!” said Ignatius Gallaher. “It’s six of one and half-a-dozen of the other. You ask Hogan, my boy. I showed him a bit about London when he was over there. He’d open your eye. . . . I say, Tommy, don’t make punch of that whisky: liquor up.”

“No, really. . . . ”

“O, come on, another one won’t do you any harm. What is it? The same again, I suppose?”

“Well . . . all right.”

“François, the same again. . . . Will you smoke, Tommy?”

Ignatius Gallaher produced his cigar-case. The two friends lit their cigars and puffed at them in silence until their drinks were served.

“I’ll tell you my opinion,” said Ignatius Gallaher, emerging after some time from the clouds of smoke in which he had taken refuge, “it’s a rum world. Talk of immorality! I’ve heard of cases, what am I saying?, I’ve known them: cases of . . . immorality. . . . ”

Ignatius Gallaher puffed thoughtfully at his cigar and then, in a calm historian’s tone, he proceeded to sketch for his friend some pictures of the corruption which was rife abroad. He summarised the vices of many capitals and seemed inclined to award the palm to Berlin. Some things he could not vouch for (his friends had told him), but of others he had had personal experience. He spared neither rank nor caste. He revealed many of the secrets of religious houses on the Continent and described some of the practices which were fashionable in high society and ended by telling, with details, a story about an English duchess, a story which he knew to be true. Little Chandler as astonished.

“Ah, well,” said Ignatius Gallaher, “here we are in old jog-along Dublin where nothing is known of such things.”

“How dull you must find it,” said Little Chandler, “after all the other places you’ve seen!”

Well,” said Ignatius Gallaher, “it’s a relaxation to come over here, you know. And, after all, it’s the old country, as they say, isn’t it? You can’t help having a certain feeling for it. That’s human nature. . . . But tell me something about yourself. Hogan told me you had . . . tasted the joys of connubial bliss. Two years ago, wasn’t it?”

Little Chandler blushed and smiled.

“Yes,” he said. “I was married last May twelve months.”

“I hope it’s not too late in the day to offer my best wishes,” said Ignatius Gallaher. “I didn’t know your address or I’d have done so at the time.”

He extended his hand, which Little Chandler took.

“Well, Tommy,” he said, “I wish you and yours every joy in life, old chap, and tons of money, and may you never die till I shoot you. And that’s the wish of a sincere friend, an old friend. You know that?”

“I know that,” said Little Chandler.

“Any youngsters?” said Ignatius Gallaher.

Little Chandler blushed again.

“We have one child,” he said.

“Son or daughter?”

“A little boy.”

Ignatius Gallaher slapped his friend sonorously on the back.

“Bravo,” he said, “I wouldn’t doubt you, Tommy.”

Little Chandler smiled, looked confusedly at his glass and bit his lower lip with three childishly white front teeth.

“I hope you’ll spend an evening with us,” he said, “before you go back. My wife will be delighted to meet you. We can have a little music and, , ”

“Thanks awfully, old chap,” said Ignatius Gallaher, “I’m sorry we didn’t meet earlier. But I must leave tomorrow night.”

“Tonight, perhaps . . . ?”

“I’m awfully sorry, old man. You see I’m over here with another fellow, clever young chap he is too, and we arranged to go to a little card-party. Only for that . . . ”

“O, in that case . . . ”

“But who knows?” said Ignatius Gallaher considerately. “Next year I may take a little skip over here now that I’ve broken the ice. It’s only a pleasure deferred.”

“Very well,” said Little Chandler, “the next time you come we must have an evening together. That’s agreed now, isn’t it?”

“Yes, that’s agreed,” said Ignatius Gallaher. “Next year if I come, parole d’honneur.”

“And to clinch the bargain,” said Little Chandler, “we’ll just have one more now.”

Ignatius Gallaher took out a large gold watch and looked a it.

“Is it to be the last?” he said. “Because you know, I have an a.p.”

“O, yes, positively,” said Little Chandler.

“Very well, then,” said Ignatius Gallaher, “let us have another one as a deoc an doruis, that’s good vernacular for a small whisky, I believe.”

Little Chandler ordered the drinks. The blush which had risen to his face a few moments before was establishing itself. A trifle made him blush at any time: and now he felt warm and excited. Three small whiskies had gone to his head and Gallaher’s strong cigar had confused his mind, for he was a delicate and abstinent person. The adventure of meeting Gallaher after eight years, of finding himself with Gallaher in Corless’s surrounded by lights and noise, of listening to Gallaher’s stories and of sharing for a brief space Gallaher’s vagrant and triumphant life, upset the equipoise of his sensitive nature. He felt acutely the contrast between his own life and his friend’s and it seemed to him unjust. Gallaher was his inferior in birth and education. He was sure that he could do something better than his friend had ever done, or could ever do, something higher than mere tawdry journalism if he only got the chance. What was it that stood in his way? His unfortunate timidity He wished to vindicate himself in some way, to assert his manhood. He saw behind Gallaher’s refusal of his invitation. Gallaher was only patronising him by his friendliness just as he was patronising Ireland by his visit.

The barman brought their drinks. Little Chandler pushed one glass towards his friend and took up the other boldly.

“Who knows?” he said, as they lifted their glasses. “When you come next year I may have the pleasure of wishing long life and happiness to Mr. and Mrs. Ignatius Gallaher.”

Ignatius Gallaher in the act of drinking closed one eye expressively over the rim of his glass. When he had drunk he smacked his lips decisively, set down his glass and said:

“No blooming fear of that, my boy. I’m going to have my fling first and see a bit of life and the world before I put my head in the sack, if I ever do.”

“Some day you will,” said Little Chandler calmly.

Ignatius Gallaher turned his orange tie and slate-blue eyes full upon his friend.

“You think so?” he said.

“You’ll put your head in the sack,” repeated Little Chandler stoutly, “like everyone else if you can find the girl.”

He had slightly emphasised his tone and he was aware that he had betrayed himself; but, though the colour had heightened in his cheek, he did not flinch from his friend’s gaze. Ignatius Gallaher watched him for a few moments and then said:

“If ever it occurs, you may bet your bottom dollar there’ll be no mooning and spooning about it. I mean to marry money. She’ll have a good fat account at the bank or she won’t do for me.”

Little Chandler shook his head.

“Why, man alive,” said Ignatius Gallaher, vehemently, “do you know what it is? I’ve only to say the word and tomorrow I can have the woman and the cash. You don’t believe it? Well, I know it. There are hundreds, what am I saying?, thousands of rich Germans and Jews, rotten with money, that’d only be too glad. . . . You wait a while my boy. See if I don’t play my cards properly. When I go about a thing I mean business, I tell you. You just wait.”

He tossed his glass to his mouth, finished his drink and laughed loudly. Then he looked thoughtfully before him and said in a calmer tone:

“But I’m in no hurry. They can wait. I don’t fancy tying myself up to one woman, you know.”

He imitated with his mouth the act of tasting and made a wry face.

“Must get a bit stale, I should think,” he said.

Little Chandler sat in the room off the hall, holding a child in his arms. To save money they kept no servant but Annie’s young sister Monica came for an hour or so in the morning and an hour or so in the evening to help. But Monica had gone home long ago. It was a quarter to nine. Little Chandler had come home late for tea and, moreover, he had forgotten to bring Annie home the parcel of coffee from Bewley’s. Of course she was in a bad humour and gave him short answers. She said she would do without any tea but when it came near the time at which the shop at the corner closed she decided to go out herself for a quarter of a pound of tea and two pounds of sugar. She put the sleeping child deftly in his arms and said:

“Here. Don’t waken him.”

A little lamp with a white china shade stood upon the table and its light fell over a photograph which was enclosed in a frame of crumpled horn. It was Annie’s photograph. Little Chandler looked at it, pausing at the thin tight lips. She wore the pale blue summer blouse which he had brought her home as a present one Saturday. It had cost him ten and elevenpence; but what an agony of nervousness it had cost him! How he had suffered that day, waiting at the shop door until the shop was empty, standing at the counter and trying to appear at his ease while the girl piled ladies’ blouses before him, paying at the desk and forgetting to take up the odd penny of his change, being called back by the cashier, and finally, striving to hide his blushes as he left the shop by examining the parcel to see if it was securely tied. When he brought the blouse home Annie kissed him and said it was very pretty and stylish; but when she heard the price she threw the blouse on the table and said it was a regular swindle to charge ten and elevenpence for it. At first she wanted to take it back but when she tried it on she was delighted with it, especially with the make of the sleeves, and kissed him and said he was very good to think of her.

Hm! . . .

He looked coldly into the eyes of the photograph and they answered coldly. Certainly they were pretty and the face itself was pretty. But he found something mean in it. Why was it so unconscious and ladylike? The composure of the eyes irritated him. They repelled him and defied him: there was no passion in them, no rapture. He thought of what Gallaher had said about rich Jewesses. Those dark Oriental eyes, he thought, how full they are of passion, of voluptuous longing! . . . Why had he married the eyes in the photograph?

He caught himself up at the question and glanced nervously round the room. He found something mean in the pretty furniture which he had bought for his house on the hire system. Annie had chosen it herself and it reminded him of her. It too was prim and pretty. A dull resentment against his life awoke within him. Could he not escape from his little house? Was it too late for him to try to live bravely like Gallaher? Could he go to London? There was the furniture still to be paid for. If he could only write a book and get it published, that might open the way for him.

A volume of Byron’s poems lay before him on the table. He opened it cautiously with his left hand lest he should waken the child and began to read the first poem in the book:

Hushed are the winds and still the evening gloom,

Not e’en a Zephyr wanders through the grove,

Whilst I return to view my Margaret’s tomb

And scatter flowers on the dust I love.

He paused. He felt the rhythm of the verse about him in the room. How melancholy it was! Could he, too, write like that, express the melancholy of his soul in verse? There were so many things he wanted to describe: his sensation of a few hours before on Grattan Bridge, for example. If he could get back again into that mood. . . .

The child awoke and began to cry. He turned from the page and tried to hush it: but it would not be hushed. He began to rock it to and fro in his arms but its wailing cry grew keener. He rocked it faster while his eyes began to read the second stanza:

Within this narrow cell reclines her clay,

That clay where once . . .

It was useless. He couldn’t read. He couldn’t do anything. The wailing of the child pierced the drum of his ear. It was useless, useless! He was a prisoner for life. His arms trembled with anger and suddenly bending to the child’s face he shouted:

“Stop!”

The child stopped for an instant, had a spasm of fright and began to scream. He jumped up from his chair and walked hastily up and down the room with the child in his arms. It began to sob piteously, losing its breath for four or five seconds, and then bursting out anew. The thin walls of the room echoed the sound. He tried to soothe it but it sobbed more convulsively. He looked at the contracted and quivering face of the child and began to be alarmed. He counted seven sobs without a break between them and caught the child to his breast in fright. If it died! . . .

The door was burst open and a young woman ran in, panting.

“What is it? What is it?” she cried.

The child, hearing its mother’s voice, broke out into a paroxysm of sobbing.

“It’s nothing, Annie . . . it’s nothing. . . . He began to cry . . . ”

She flung her parcels on the floor and snatched the child from him.

“What have you done to him?” she cried, glaring into his face.

Little Chandler sustained for one moment the gaze of her eyes and his heart closed together as he met the hatred in them. He began to stammer:

“It’s nothing. . . . He . . . he began to cry. . . . I couldn’t . . . I didn’t do anything. . . . What?”

Giving no heed to him she began to walk up and down the room, clasping the child tightly in her arms and murmuring:

“My little man! My little mannie! Was ’ou frightened, love? . . . There now, love! There now!… Lambabaun! Mamma’s little lamb of the world! . . . There now!”

Little Chandler felt his cheeks suffused with shame and he stood back out of the lamplight. He listened while the paroxysm of the child’s sobbing grew less and less; and tears of remorse started to his eyes.

.jpg)

James Joyce: A Little Cloud

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Archive I-J, Joyce, James, Joyce, James

.jpg)

W i l l i a m S h a k e s p e a r e

(1564-1616)

T H E S O N N E T S

21

So is it not with me as with that muse,

Stirred by a painted beauty to his verse,

Who heaven it self for ornament doth use,

And every fair with his fair doth rehearse,

Making a couplement of proud compare

With sun and moon, with earth and sea’s rich gems:

With April’s first-born flowers and all things rare,

That heaven’s air in this huge rondure hems.

O let me true in love but truly write,

And then believe me, my love is as fair,

As any mother’s child, though not so bright

As those gold candles fixed in heaven’s air:

Let them say more that like of hearsay well,

I will not praise that purpose not to sell.

![]()

kempis poetry magazine

More in: -Shakespeare Sonnets

.jpg)

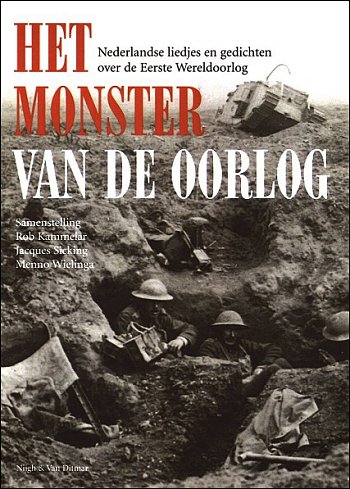

HET MONSTER VAN DE OORLOG

door Ed Schilders

De Eerste Wereldoorlog. Nederland bleef neutraal, wat zoveel betekende dat we niet in oorlog waren maar ‘gemobiliseerd’. Het is de tijd van miliciens, landweermannen, en rijwielbataljons die onze landsgrenzen bewaken. Ook toen al waren dat ‘onze jongens’. Onderschat ze niet. ‘Daar komen de jongens van Holland ’an’ is zowel de titel als de beginregel van een marslied, en de tweede regel rijmt daarop met ‘De grond en de huizen, ze trillen er van’. Het eindigt zo: ‘Zij vechten niet graag, maar alleen als het moet,/ Dan slaan zij er op, en dan vechten zij goed.’ De samenstellers van de bloemlezing Het monster van de oorlog hebben deze liedtekst opgenomen als een voorbeeld van ‘gezagsgetrouwe’ lyriek, en wel uit de in 1915 ‘op last van den Minister van Oorlog’ uitgegeven Zangbundel voor het Nederlandsche Leger.

Verreweg het overgrote deel van de bloemlezing valt gelukkig niet onder die departementale noemer van gezagsgetrouwheid. Mogen de gruwelen van Verdun en Ieper aan ons land voorbij zijn gegaan, de ‘Grote Oorlog’ was ook een tijd van armoede en werkloosheid, van broodkaarten en aardappelnood, van dienstweigeraars en in het gevang uitgeboet pacifisme. Er is vrijwel geen aspect van die in het nauw gebrachte samenleving of het is door dichter of cabaretier, door revue-artiest of straatzanger indertijd bezongen, en nu in Het monster van de oorlog gebloemleesd. De samenstellers hebben gekozen voor een brede interpretatie van ‘lyriek’, en hun bundel wordt daardoor wat de literaire kwaliteit aangaat onevenwichtig. Van J.C. Bloem tot de anonieme straatzanger. In het algemeen geldt voor deze verzameling echter: hoe dichter bij de straat, hoe indringender het uitzicht op het leven in gemobiliseerd Nederland. Want moest Gorter nou zo nodig geplukt worden voor deze ruiker? Of de ode aan de Franse maarschalk Joffre, een gedicht dat Marsman zelf al verdacht van ‘pathetiek’? Wij hebben nu eenmaal niet in de loopgraven liggen trillen. Wij hebben geen klassiekers als John McCrae en zijn klaprozen in Vlaanderen. Maar Nederland had wel honger en dienstweigeraars. We hadden Speenhoff (de Bob Hope van de landweermannen), Pisuisse, Charivarius, en Dirk Witte, wiens zwangere Jopie (uit ‘De peren’) helaas niet in de bloemlezing figureert, maar die keurig wordt vervangen door de meisjes in de Scheveningse duinen. Want ook daar kwamen de jongens. En vooral: de liedjes die op straat gezongen en verkocht werden door anoniem gebleven scharrelaars. Het is toch voornamelijk die alledaagsheid, het leven met aardappelnood, rats en kuch, en ‘per dag ’n kwart ons/ Vet van oude zilverbons’, die Het monster van de oorlog tot een bijzondere bloemlezing maakt.

Rob Kammelar e.a. (red.): Het monster van de oorlog – Nederlandse liedjes en gedichten over de Eerste Wereldoorlog – Nijgh & Van Ditmar – ISBN 90 388 0020 7

Eerder gepubliceerd in de Volkskrant

Ed Schilders: Het monster van de oorlog

k e m p i s p o e t r y m a g a z i n e

More in: Ed Schilders, POETRY ARCHIVE, WAR & PEACE

Jef van Kempen

Drie gedichten

Concept

Geen woord teveel

overdacht hij zijn daden,

ging stil voorbij

niet gezien en

niet gewogen.

Welk kind

werd niet verwekt

met de sombere schoonheid

van de dood voor ogen?

Suïcide

Het was geheel in overeenstemming met

wat zijn hart voelde maar wat zijn hoofd

vergat.

Omdat elk bewijs ontbrak, kreeg zijn onrust

geen warm onthaal, had hij als bron van kennis

en als gangmaker van valse praktijken afgedaan.

Zijn opvatting dat met het oog op de vooruitgang

geen genade kon worden verleend

(tenminste niet uit misplaatst medelijden)

dat in het licht van de resultaten van de samenspraak

van lichaam en ziel

een samenhang werd verondersteld

van gevoel en waarneming,

maakte zijn mistroostigheid alles onthullend,

waarbij de goede verstaander niet dient

te vergeten de invloed van gebrek aan slaap,

totdat hij als een schim fluisterend

zegde te zijn misleid en zich over te geven

aan een lichaam zonder een spoor van lust en

bandeloosheid, als een alledaagse omstandigheid

onherroepelijk hangend

aan het plafond

van zijn dromen.

My Lai

Het was een ongewone tijd.

Een goede lijkenscore

daar draaide het om,

daar werd niet stiekem

over gedaan.

Zo’n oorlog was het.

We sneden de oren af

van vrouwen en kinderen

en hingen die aan een ketting

om onze nek.

Zo’n oorlog was het.

Het was een ongewone tijd.

Jef van Kempen (1948) publiceerde poëzie, biografische artikelen, essays en literaire bloemlezingen. Daarnaast is hij actief als beeldend kunstenaar. Jef van Kempen is medeoprichter en redacteur van o.a. de poëziewebsite: KEMP=MAG – kempis poetry magazine ( www.kempis.nl ) en van de website Antony Kok Magazine ( www. antonykok.nl ) In 1966 publiceerde hij zijn eerste dichtbundel: Wiet. In 2010 verschijnt een verzamelbundel met gedichten en illustraties: Laatste bedrijf, gedichten 1963-2009 bij uitgeverij Art Brut, Postbus 117, 5120 AC Rijen, ISBN: 978-90-76326-04-7.

k e m p i s p o e t r y m a g a z i n e

More in: Kempen, Jef van

.jpg)

M u l t a t u l i

(Eduard Douwes Dekker, 1820-1887)

Saïdjah’s Zang

Ik weet niet waar ik sterven zal.

Ik heb de grote zee gezien aan de zuidkust,

toen ik daar was met mijn

vader om zout te maken.

Als ik sterf op de zee,

en men werpt mijn lichaam in het diepe water,

zullen er haaien komen.

Ze zullen rondzwemmen om mijn lijk,

en vragen: `Wie van ons zal het

lichaam verslinden dat daar daalt in het water?’

Ik zal ‘t niet horen.

Ik weet niet waar ik sterven zal.

Ik heb het huis zien branden van Pa-ansoe,

dat hij zelf had aangestoken omdat hij mataglap was.

Als ik sterf in een brandend huis,

zullen er gloeiende stukken hout

neervallen op mijn lijk.

En buiten het huis zal een groot geroep zijn

van mensen die water werpen om het vuur te doden.

Ik zal ‘t niet horen.

Ik weet niet waar ik sterven zal.

Ik heb de kleine Si-oenah zien vallen uit de klappa-boom,

toen hij een klappa plukte voor zijn moeder.

Als ik val uit een klappa-boom,

zal ik dood nederliggen aan de voet in

de struiken, als Si-oenah.

Dan zal mijn moeder niet schreien,

want zij is dood.

Maar anderen zullen roepen: `Zie,

daar ligt Saïdjah!’ met harde stem.

Ik zal ‘t niet horen.

Ik weet niet waar ik sterven zal.

Ik heb het lijk gezien van Pa-lisoe,

die gestorven was van hoge

ouderdom, want zijne haren waren wit.

Als ik sterf van ouderdom, met witte haren,

zullen de klaagvrouwen om mijn lijk staan.

En zij zullen misbaar maken als

de klaagvrouwen bij Pa-lisoe’s lijk.

En ook de kleinkinderen zullen schreien,

zeer luid.

Ik zal ‘t niet horen.

Ik weet niet waar ik sterven zal.

Ik heb velen gezien te Badoer,

die gestorven waren.

Men kleedde hen in een wit kleed,

en begroef hen in de grond.

Als ik sterf te Badoer,

en men begraaft mij buiten de dessa,

oostwaarts tegen de heuvel,

waar ‘t gras hoog is,

Dan zal Adinda daar voorbijgaan,

en de rand van haar sarong zal

zachtkens voortschuiven langs het gras…

Ik zal het horen.

.jpg)

Multatuli gedichten

kempis poetry magazine

photo jefvankempen

Sara Bidaoui

Eerste Tilburgse Kinderstadsdichter

28 januari 2010

Sara Bidaoui (13) is de eerste kinderstadsdichter van Tilburg. Sara was één van de drie genomineerden kinderen voor deze nieuwe functie. De functie kinderstadsdichter was de hoofdprijs van een gedichtenwedstrijd met als onderwerp de stad Tilburg.

De wedstrijd was een initiatief van Stichting Cools, Cultuurconcepten.nl en de bibliotheek Midden-Brabant.

Sara won de wedstrijd met het gedicht: ‘Tilburg mijn stad, mijn thuis’. Ze mag haar functie bekleden tot augustus 2011. De tweede prijs ging naar Liz Abels en de derde prijs naar Lina van Bussel.

Tilburg: mijn stad, mijn thuis

Ik wil je zoveel vertellen

Je laten zien wat je mist

Maar het enige waar ik op kom is:

Mijn stad, mijn thuis

Ik wil je zoveel vertellen

Al is het maar op papier

Ik wil je laten zien

Mijn mooiste plekken hier

Maar het enige wat ik kan zeggen is:

Mijn stad, mijn thuis

Ik wil je zoveel vertellen

Maar ik weet niet hoe en wat

Woorden zat

Maar in mijn hoofd maar één gedachte:

Tilburg

Mijn stad, mijn thuis

Sara Bidaoui

![]()

Meer informatie op de website van Stichting Dr PJ Cools

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Bidaoui, Sara, City Poets / Stadsdichters, Kinderstadsdichters / Children City Poets

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature