Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

Presentatie nieuwe dichtbundel Nick J. Swarth

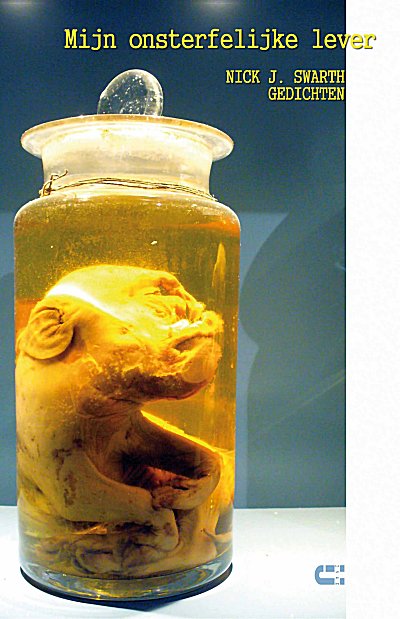

Mijn onsterfelijke lever

Op woensdag 16 mei 2012 vindt de presentatie plaats van de nieuwe dichtbundel van Nick J. Swarth, ‘Mijn onsterfelijke lever’ (Uitgeverij IJzer, Utrecht). De dichtbundel kwam mede tot stand dankzij de steun van 73 donateurs, die een bijdrage leverden op voordekunst.nl, een site voor crowdfunding. Dankzij hen is ‘Mijn onsterfelijke lever’ in de boekhandel verkrijgbaar aan een uiterst scherpe prijs: EUR 10.

De lancering vindt plaats in Paradox, Telegraafstraat 62, 5038 BM Tilburg. Daar kan men terecht vanaf 20:00. Aanvang 20:30.

De presentatie van de avond is in de capabele handen van ‘juffrouw’ Janine Ensslin. Ze stond eerder garant voor het geslaagde crowdfunding-traject, dat de bundel mede mogelijk maakte. Zij zal onder andere spreken met Efrat Zehavi. Deze in Rotterdam woonachtige beeldende kunstenares werkt aan een animatiefilm op basis van teksten van Swarth. In Paradox toont zij de eerste resultaten van dit work in progress.

De dichter zelf treedt ook voor het voetlicht. Hij draagt een aantal kakelverse teksten voor, daarin bijgestaan op gitaar door instant composer Frank Crijns.

En omdat zo’n bundelpresentatie toch een feestje is, wordt de avond afgesloten met een vitaal optreden van de band Zibabu. Zibabu wortelt in de underground en treedt doorgaans op in kraakpanden, of tijdens demonstraties, spoorblokkades en wat dies meer zij. Rocking On Burning Barricades. Gedreven, vuurvast en voor geen gat te vangen. Unplugg your brain, baby!

Nick J. Swarth is dichter en performer. Werk in druk: ‘¡Mondo Manga!’ (gedichten, 2010); ‘Horror Vacui’, registratie van een schandaalverwekkend kunstproject (i.s.m. J. de Leijer, 2008); ‘Naked City Poems’ (stadsgedichten, 2007); ‘De napalmsessies’ (bundel-dvd, 2005). Swarth is de voice ‘n’ noise van het illustere guerrilla rock trio Betonfraktion. I.s.m. typograaf Sander Neijnens verwezenlijkte hij ‘Plekgedichten’ in de openbare ruimte.

Nick J. Swarth

MIJN ONSTERFELIJKE LEVER

Gedichten & tekeningen

Omslagontwerp: Nick J. Swarth

Foto’s omslag: Nick J. Swarth

Typografie: Bureau Vanbinnen

Uitgeverij IJzer, Utrecht | 2012

ISBN 978 90 8684 086 1

NUR 305

Paperback, 64 blz

Prijs: € 10

MIJN ONSTERFELIJKE LEVER werd mogelijk gemaakt door de 73 donateurs die hun geloof in de maker en zijn werk kracht bijzetten op Voordekunst.nl

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Swarth, Nick J.

Ton van Reen

vannacht

Vannacht

zijn wij

over het ijs gelopen

er was

een vale maan

die traag

langs zijn koude licht

naar beneden schreed

jouw mistige adem

tekende draden

over je bedroomd

gezicht

schiep een waaiend

mozaïek

van zomaar

bij elkaar gezette

brandende

kaarsen

daartussen leek het

of de haren

rond je ogen

in kool getekend waren

de maan werd

een zware magneet

die de ijzeren deuren

in mijn hart

opentrok

later

heb ik jou

over de schuimsneeuwen

drempel van mijn huis

gedragen

Uit: Ton van Reen, Blijvend vers, Verzamelde gedichten (1965-2007). Uitgeverij De Contrabas, 2011, ISBN 9789079432462, 144 pagina’s, paperback

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive Q-R, Reen, Ton van

Hans Lodeizen

(1924-1950)

Toen ik nog . . .

(fragment)

ik heb zijn handen een hand gegeven

ik ben in zijn ogen gevangen

ik ben in zijn oren verward

ik ben in zijn lichaam verdwaald

in zijn lichaam verdronken.

Hans Lodeizen poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive K-L

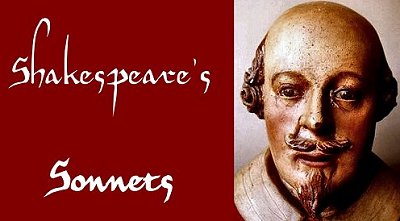

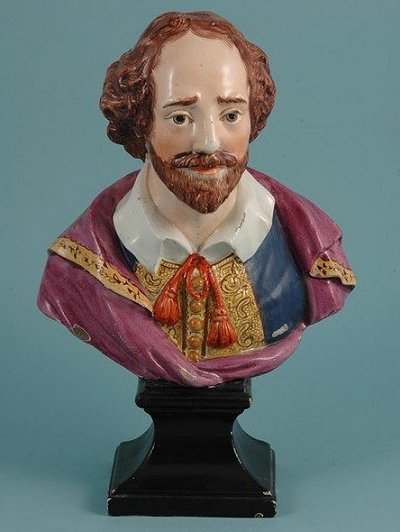

William Shakespeare

(1564-1616)

THE SONNETS

127

In the old age black was not counted fair,

Or if it were it bore not beauty’s name:

But now is black beauty’s successive heir,

And beauty slandered with a bastard shame,

For since each hand hath put on nature’s power,

Fairing the foul with art’s false borrowed face,

Sweet beauty hath no name no holy bower,

But is profaned, if not lives in disgrace.

Therefore my mistress’ eyes are raven black,

Her eyes so suited, and they mourners seem,

At such who not born fair no beauty lack,

Slandering creation with a false esteem,

Yet so they mourn becoming of their woe,

That every tongue says beauty should look so.

![]()

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: -Shakespeare Sonnets

Jan Campert

(1902- 1943)

Het lied der achttien doden

Een cel is maar twee meter lang

en nauw twee meter breed,

wel kleiner nog is het stuk grond,

dat ik nu nog niet weet,

maar waar ik naamloos rusten zal,

mijn makkers bovendien,

wij waren achttien in getal,

geen zal de avond zien.

O lieflijkheid van licht en land,

van Hollands vrije kust,

eens door de vijand overmand

had ik geen uur meer rust.

Wat kan een man oprecht en trouw,

nog doen in zulk een tijd ?

Hij kust zijn kind, hij kust zijn vrouw

en strijd den ijlden strijd.

Ik wist de taak die ik begon,

een taak van moeite zwaar,

maar ‘t hart dat het niet laten kon

schuwt nimmer het gevaar;

het weet hoe eenmaal in dit land

de vrijheid werd geëerd,

voordat de vloekbre schennershand

het anders heeft begeerd.

Voordat die eeden breekt en bralt

het miss’lijk stuk bestond

en Holland’s landen binnenvalt

en brandschat zijnen grond;

voordat die aanspraak maakt op eer

en zulk Germaans gerief

ons volk dwong onder zijn beheer

en plunderde als een dief.

De Rattenvanger van Berlijn

pijpt nu zijn melodie, –

zoo waar als ik straks dood zal zijn,

de liefste niet meer zie

en niet meer breken zal het brood

en slapen mag met haar –

verwerp al wat hij biedt of bood

die sluwe vogelaar.

Gedenk die deze woorden leest

mijn makkers in den nood

en die hen nastaan ‘t allermeest

in hunnen rampspoed groot,

gelijk ook wij hebben gedacht

aan eigen land en volk –

er daagt een dag na elke nacht,

voorbij trekt iedre wolk.

Ik zie hoe ‘t eerste morgenlicht

door ‘t hooge venster draalt.

Mijn God, maak mij het sterven licht –

en zoo ik heb gefaald

gelijk een elk wel falen kan,

schenk mijn dan Uw genâ,

opdat ik heenga als een man

als ik voor de loopen sta.

Jan Campert (1902-1943): Nederlands letterkundige, journalist en dichter, werd gearresteerd wegens hulp aan joden en ter dood gebracht te Neuengamme. Toen Campert op 5 maart 1941 de Duitse bekendmaking las over de voltrokken doodvonnissen van vijftien verzetslieden van de illegale groep De Geuzen en drie stakers van de Februaristaking, schreef hij het gedicht De achttien dooden.

Bernardus IJzerdraad (49 jaar), gobelinrestaurateur

Jan Kijne (46 jaar), vertegenwoordiger

Ary Kop (40 jaar), verzekeringsagent

Jacob van der Ende (22 jaar), schilder

Leendert Keesmaat (29 jaar), onderwijzer

Hendrik Wielenga (37 jaar), electrotechnicus

Johannes Smit (30 jaar), monteur

Frans Rietveld (36 jaar), slijper

Leendert Langstraat (31 jaar), machinebankwerker

Jan Wernard van den Bergh (47 jaar), slijper

Albertus Johannes de Haas (37 jaar), metaalgieter

Reijer Bastiaan van der Borden (32 jaar), hulppolitieagent

Nicolaas Arie van der Burg (36 jaar), vertegenwoordiger

George de Boon (21 jaar), metaalbewerker

Dirk Kouvenhoven (24 jaar), stoker

E. Hellendoorn

Hermanus Mattheus Hendricus Coenradi, elektricien

J. Eyl

Jan Campert poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: *War Poetry Archive, Archive C-D, Campert, Remco, REPRESSION OF WRITERS, JOURNALISTS & ARTISTS

Stabilitas loci

Lamellen breken zonlicht. Buiten ballen kinderen.

Ik kan ze horen, vreugdekreetjes om ik weet niet wat.

De kamer droomt hartgrondig dat zij een kajuit is.

Op straat speelt het leven zich af als een parodie

op zichzelf. In boodschappentassen herkennen

tussen karton ajuin en prei zich als verre verwanten.

Lippen praten elkaar naar de mond met woorden

leeg als kraters. In de verte stap iemand een kerk binnen.

Dezelfde wereld is er anders voor wie zich welkom weet.

Hier zwijgt de telefoon met het ritme van een goederentrein.

Ik huiver van begrip: nooit is het te laat om te blijven

waar men is. Nooit te laat is het. Het is altijd tijd.

Bert Bevers

(uit Afglans – Gedichten 1972-1997, uitgeverij WEL, Bergen op Zoom, 1997, ISBN 90 6230 080 4)

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Bevers, Bert

Shakespeare Sonnet 123

No! Time, thou shalt not boast that I do change,

Thy pyramids built up with newer might

To me are nothing novel, nothing strange,

They are but dressings of a former sight:

Our dates are brief, and therefore we admire,

What thou dost foist upon us that is old,

And rather make them born to our desire,

Than think that we before have heard them told:

Thy registers and thee I both defy,

Not wond’ring at the present, nor the past,

For thy records, and what we see doth lie,

Made more or less by thy continual haste:

This I do vow and this shall ever be,

I will be true despite thy scythe and thee.

Shakespeare Sonnet 123

Nee! snoeven dat ik wankel zal niet gaan,

O Tijd: jouw pyramides nieuw gebouwd–

Modern of vreemd doen zij mij heus niet aan,

Hun kruik mag nieuw zijn, maar hun wijn is oud;

Wij leven kort, en dus bewonderen wij

Wat jij ons opdist dat op leeftijd is,

En doen er wat gewild en jong is bij,

Veel liever dan oude geschiedenis;

Jou en je leggers, nooit door mij vertrouwd,

Bevraag ik niet voor ’t nu, noch voor het toen,

Want wat jij vastlegt en wij zien is fout,

Vergroot, verkleind, door ’t steeds gehaast te doen;

Dit zweer ik nu voor eeuwig: ik blijf trouw,

En dat ondanks je zeis en ondanks jou.

Vertaling Cornelis W. Schoneveld, april 2012

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Shakespeare, Shakespeare, William

![]()

Park eren

Harde kale takken

spreken over dood

bomen blozen, bloot

en kwetsbaar in hun

tere lingerie van knoppen

winter aarzelt te vertrekken

rekt zich nog even uit als kat

en trekt soms hele gekke bekken

naar ons wandelaars, met naast ons

horden uitgelaten fris ontdooide vogels

in hoge toppen staan herrezen mezen

pas uit diepvries weggevlogen, bewogen

en spatzuiver deze terugkeer te befluiten

merels neurieën mee uit zachte kelen

zonlicht gaat nu alle grauwheid helen

door het vaak en lang te strelen

daalt vastbesloten naar beneden

nog zonder warmte, nog even

zonder warmte, tot het kille

eindelijk wordt ingehaald

parkeergeld is betaald.

Freda Kamphuis

(c)2012 Freda Kamphuis

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive K-L, Kamphuis, Freda

Theodor Fontane

(1819–1898)

Mein Herze, glaubt’s, ist nicht erkaltet

Mein Herze, glaubt’s, ist nicht erkaltet,

Es glüht in ihm so heiß wie je,

Und was ihr drin für Winter haltet,

Ist Schein nur, ist gemalter Schnee.

Doch, was in alter Lieb’ ich fühle,

Verschließ ich jetzt in tiefstem Sinn,

Und trag’s nicht fürder ins Gewühle

Der ewig kalten Menschen hin.

Ich bin wie Wein, der ausgegoren:

Er schäumt nicht länger hin und her,

Doch was nach außen er verloren,

Hat er an innrem Feuer mehr.

Theodor Fontane poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive E-F, Theodor Fontane

William Shakespeare

(1564-1616)

THE SONNETS

126

O thou my lovely boy who in thy power,

Dost hold Time’s fickle glass his fickle hour:

Who hast by waning grown, and therein show’st,

Thy lovers withering, as thy sweet self grow’st.

If Nature (sovereign mistress over wrack)

As thou goest onwards still will pluck thee back,

She keeps thee to this purpose, that her skill

May time disgrace, and wretched minutes kill.

Yet fear her O thou minion of her pleasure,

She may detain, but not still keep her treasure!

Her audit (though delayed) answered must be,

And her quietus is to render thee.

![]()

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: -Shakespeare Sonnets

![]()

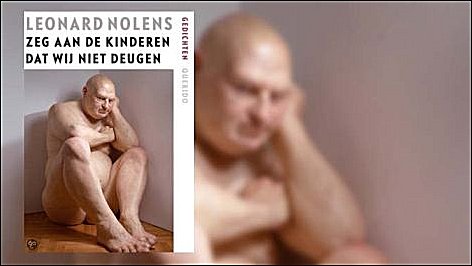

Prijs der Nederlandse Letteren 2012 voor

Leonard Nolens

De Vlaamse dichter en dagboekschrijver Leonard Nolens (Bree, 11 april 1947) ontvangt dit najaar de Prijs der Nederlandse Letteren. Aan de prijs is een geldbedrag verbonden van 40.000 euro.

Dit maakte de voorzitter van het Comité van Ministers van de Taalunie, de Vlaamse Minister van Onderwijs Pascal Smet woensdagavond bekend in een uitverkochte Bourlaschouwburg in Antwerpen, waar de 65ste verjaardag van Nolens gevierd werd.

‘Nolens doet het Nederlands opnieuw zingen’, zo stelt de jury onder voorzitterschap van Herman Pleij. De jury noemt Nolens een ‘uitzonderlijk dichter en zeer begenadigd voorlezer’ en kenmerkt zijn werk als ‘een levenslange worsteling in taal en een zoektocht naar de eigen identiteit en die van de ander’.

De laureaat werd woensdagochtend overdonderd door het bericht. Hij zat in zijn werkkamer toen minister Smet belde: ‘Het was of de buitenwereld op een onwezenlijke manier binnenkwam’.

Bij de aankondiging in de Bourlaschouwburg zei minister Smet: ‘Leonard Nolens wijdt zich al zijn hele leven aan wat allicht economisch een van de meest nutteloze bezigheden is, en daar heb je in deze tijden uitzonderlijk veel lef voor nodig. Maar zonder taal, gevoed door taalkunstenaars, is er van economie waarschijnlijk helemaal geen sprake’.

Nolens heeft sinds zijn debuut in 1969 een indrukwekkend oeuvre opgebouwd. Zijn bundel Liefdes verklaringen (1990) werd in Nederland bekroond met de Jan Campertprijs en in België met de Driejaarlijkse Prijs van de Vlaamse Gemeenschap voor poëzie. In 1997 kreeg hij de Constantijn Huygensprijs voor zijn gehele oeuvre. In 2008 werd hem de VSB Poëzieprijs toegekend.

De Nederlandse Taalunie kent de Prijs der Nederlandse Letteren om de drie jaar toe aan een auteur van wie het werk een belangrijke plaats inneemt in de Nederlandstalige literatuur. De ene keer overhandigt de Belgische koning de prijs, de andere keer de Nederlandse koningin.

De jury van de Prijs der Nederlandse Letteren 2012 bestaat uit Herman Pleij (voorzitter), emeritus hoogleraar historische Nederlandse letterkunde, Universiteit van Amsterdam; Chandra van Binnendijk, publicist, redacteur in Suriname; Leen van Dijck, directeur Letterenhuis Antwerpen; Iris van Erve, docent Nederlands, hoofdredacteur Passionate Magazine, adviseur Nederlands Letterenfonds; Judit Gera, hoogleraar moderne Nederlandse Letteren aan de Universiteit van Boedapest, literair vertaler; Ruth Joos, radiomaker bij de VRT; Michiel van Kempen, bijzonder hoogleraar West-Indische Letteren Universiteit van Amsterdam; Hans Vandevoorde, docent Nederlandse literatuur Vrije Universiteit Brussel.

Leonard Nolens is sinds de instelling van de Prijs der Nederlandse Letteren in 1956 de twintigste laureaat. De eerdere laureaten waren: Herman Teirlinck (1956), A. Roland Holst (1959), Stijn Streuvels (1962), J.C. Bloem (1965), Gerard Walschap (1968), Simon Vestdijk (1971), Marnix Gijsen (1974), Willem Frederik Hermans (1977), Maurice Gilliams (1980), Lucebert (1983), Hugo Claus (1986), Gerrit Kouwenaar (1989), Christine D’Haen (1992), Harry Mulisch (1995), Paul de Wispelaere (1998), Gerard Reve (2001), Hella S. Haasse (2004),Jeroen Brouwers (2007) en Cees Nooteboom (2009).

Het Comitë van Ministers van de Nederlandse Taalunie bestaat uit Pascal Smet, Vlaams minister van Onderwijs, Jeugd, Gelijke Kansen en Brussel (voorzitter); Joke Schauvliege, Vlaams minister van Leefmilieu, Natuur en Cultuur; Marja van Bijsterveldt-Vliegenthart, Nederlands minister van Onderwijs, Cultuur en Wetenschap; Halbe Zijlstra, Nederlands staatssecretaris van Onderwijs, Cultuur en Wetenschap.

De Nederlandse Taalunie is een beleidsorganisatie waarin Nederland, Vlaanderen en Suriname samenwerken op het gebied van de Nederlandse taal en letteren en het onderwijs in en van het Nederlands. De Taalunie ziet het als haar opdracht om ervoor te zorgen dat alle Nederlandssprekenden hun taal op een doeltreffende manier kunnen gebruiken. Meer informatie over de Taalunie is te vinden op www.taalunieversum.org

‘Leonard Nolens doet het Nederlands opnieuw zingen. Hij is een uitzonderlijk dichter, een begenadigd voorlezer en zijn werk kenmerkt zich als een levenslange worsteling in taal en een zoektocht naar de eigen identiteit en die van de ander’. (Citaat van de jury van de Prijs der Nederlandse Letteren 2012)

Leonard Nolens (Bree, 1947) debuteerde in 1969 met de bundel Orpheushanden en heeft in de jaren daarop een indrukwekkend oeuvre opgebouwd. Zijn bundel Liefdes verklaringen (1990) werd in Nederland bekroond met de Jan Campertprijs en in België met de Driejaarlijkse Staatsprijs. In 1997 kreeg Nolens de Constantijn Huygensprijs voor zijn gehele oeuvre, in 2008 werd hem de VSB Poëzieprijs toegekend voor zijn bundel Bres (2007), de bundel die tien jaar lang een ‘dichtbundel in wording’ was, en waarvan delen in eerdere bundels verschenen.

‘Als de Vlaamse dichter Leonard Nolens schrijft, vangt een fluisterend zingen aan. Met schrijnende refreinen, welluidende zinnen en een vreugdevolle melodie.’ NRC Handelsblad

poëzie:

Orpheushanden (1969)

De muzeale minnaar (1973)

Twee vormen van zwijgen (1975)

Incantatie (1977)

Alle tijd van de wereld. een poëtica (1979)

Hommage (1981)

Vertigo (1983)

De gedroomde figuur (1986)

Geboortebewijs (1988)

Liefdes verklaringen (1990)

Hart tegen hart. Gedichten 1975-1990 (1991)

Tweedracht (1992)

Honing en as (1994)

En verdwijn met mate (1996)

De liefdesgedichten van Leonard Nolens (1997)

Hart tegen hart. Gedichten 1975-1996 (1998)

Voorbijganger (1999)

Manieren van leven (2001)

Derwisj (2003)

Laat alle deuren op een kier. Verzamelde gedichten (2004)

Een dichter in Antwerpen en andere gedichten (2005)

Een fractie van een kus (2007, Gedichtendagbundel)

Bres (2007)

Woestijnkunde (2008)

autobiografisch:

Stukken van mensen. Dagboek 1979-1982 (1989)

Blijvend vertrek. Dagboek 1983-1989 (1993)

De vrek van Missenburg. Dagboek 1990-1993 (1995)

Een lastig portret. Dagboek 1994-1996 (1998)

Dagboek van een dichter 1979-2007 (2009)

Jij bent schatrijk geboren

Jij en ik, dat is twee

Plus dit. Dat is drie. Dat is vragen

Om ruzie, men komt er niet uit.

Wij zitten perplex in elkaar.

Wij maken hetzelfde misbaar.

Jij en ik dat is een.

Jij bent schatrijk geboren

En kocht mij met gemak.

Dat zet ik je betaald

Op deze rekening.

Ik ben geen slapend geld

Vandaag, ik handel in ons.

Ik werk mij in het zweet

Van jou, ik bid en vloek mij

Uit de naad van ons,

Ik maak je winst op de markt.

Jij bent wat ik hier tel,

Mijn tol, mijn kapitaal.

Ik viel jou in de schoot

Van goud, ik woeker met wissels

Van ons en koop je terug

Nu ik ons doorverkoop

Aan vreemden, de truc is gelukt.

Wij staan op hetzelfde biljet.

Leonard Nolens

uit: ‘Derwisj’, 2003

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive M-N, Art & Literature News

William Shakespeare Sonnet 30

When to the sessions of sweet silent thought

I summon up remembrance of things past,

I sigh the lack of many a thing I sought,

And with old woes new wail my dear time’s waste:

Then can I drown an eye (unused to flow)

For precious friends hid in death’s dateless night,

And weep afresh love’s long since canceled woe,

And moan th’ expense of many a vanished sight

Then can I grieve at grievances foregone,

And heavily from woe to woe tell o’er

The sad account of fore-bemoanèd moan,

Which I new pay as if not paid before.

But if the while I think on thee, dear friend,

All losses are restored and sorrows end.

William Shakespeare Sonnet 30

Daag ik ter zitting van gemijmer zoet

Herinnering aan zaken lang vergaan,

Dan zucht ik diep om wat ik missen moet,

En lijd nieuw leed om oude tijd verdaan.

Dan laat ik graag een traan (die niet gauw vloeit)

Om vrienden in hun doodsnacht zonder tijd,

Beween weer liefde mij al lang ontgroeid,

En treur om schuld door veel vergetelheid.

Dan klaag ik graag om een belegen klacht,

En tel bedrukt weer neer, van leed tot leed,

De droeve som van wat oud onheil bracht,

Die ‘k kwijt alsof ik die niet eerder kweet.

Maar denk ik dan aan jou, mijn liefste vriend,

Zijn tranen weg, verliezen terugverdiend.

Vertaald door Cornelis W. Schoneveld,

Bestorm mijn hart, (2008, p53), herziening feb. 2012

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Shakespeare, Shakespeare, William

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature