Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

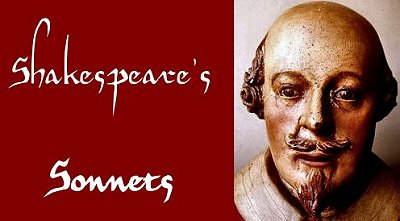

William Shakespeare

(1564-1616)

THE SONNETS

Sonnet 135

Whoever hath her wish, thou hast thy will,

And ‘Will’ to boot, and ‘Will’ in over-plus,

More than enough am I that vex thee still,

To thy sweet will making addition thus.

Wilt thou whose will is large and spacious,

Not once vouchsafe to hide my will in thine?

Shall will in others seem right gracious,

And in my will no fair acceptance shine?

The sea all water, yet receives rain still,

And in abundance addeth to his store,

So thou being rich in will add to thy will

One will of mine to make thy large will more.

Let no unkind, no fair beseechers kill,

Think all but one, and me in that one ‘Will.’

![]()

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: -Shakespeare Sonnets

Ernst Stadler

(1883-1914)

Beata Beatrix

D. G. R.

Dämmerläuten schüttet in den veilchenblauen Abend

weiße Blütenflocken. Kleine Flocken

blank wie Muschelperlen rieseln· tanzen·

schwärmen weich wie dünne blasse Daunen·

wirbelnd· wölkend. Schwere Blütenbäume

streuen goldne Garben. Wilde Gärten

tragen mich in blaue Wundernächte·

große wilde Gärten. Tiefe Beete

schwanken brennend auf· wie Traumgewässer

still und spiegelnd. Silberkähne heben

mich von braunen Uferwiesen

in das Leuchten. Über Scharlachfluten

dunklen Mohns· der rot in Flammensäulen

züngelt· treibt der Nachen. Bleiche Lilien

tropfen schillernd drüberhin wie Wellen.

Düfte aus kristallnen Nächten tauchend·

schlingen wirr und hängen sich ins Haar·

und sie locken . . leise· leise . .

und die grünen klaren Tiefen flimmern . .

Purpurstrahlen schießen . . leise sink ich . .

süß umfängt mich müder Laut von Geigen . .

schwingt· sinkt· gleitende Paläste

funkeln fern. Licht stürzt

über mich. Weit· grün

schwebt ein Glänzen .

1904

Ernst Stadler poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: *War Poetry Archive, - Archive Tombeau de la jeunesse, Archive S-T, Archive S-T, Stadler, Ernst

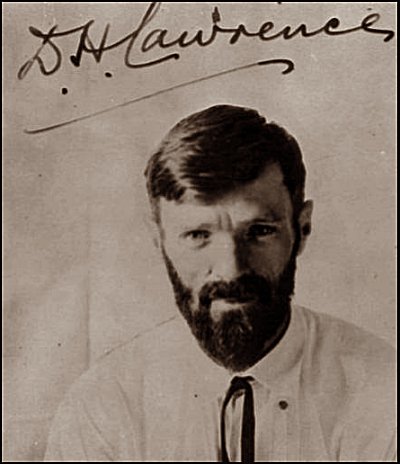

D. H. Lawrence

(1885-1930)

Whales Weep Not!

They say the sea is cold, but the sea contains

the hottest blood of all, and the wildest, the most urgent.

All the whales in the wider deeps, hot are they, as they urge

on and on, and dive beneath the icebergs.

The right whales, the sperm-whales, the hammer-heads, the killers

there they blow, there they blow, hot wild white breath out of

the sea!

And they rock, and they rock, through the sensual ageless ages

on the depths of the seven seas,

and through the salt they reel with drunk delight

and in the tropics tremble they with love

and roll with massive, strong desire, like gods.

Then the great bull lies up against his bride

in the blue deep bed of the sea,

as mountain pressing on mountain, in the zest of life:

and out of the inward roaring of the inner red ocean of whale-blood

the long tip reaches strong, intense, like the maelstrom-tip, and

comes to rest

in the clasp and the soft, wild clutch of a she-whale’s

fathomless body.

And over the bridge of the whale’s strong phallus, linking the

wonder of whales

the burning archangels under the sea keep passing, back and

forth,

keep passing, archangels of bliss

from him to her, from her to him, great Cherubim

that wait on whales in mid-ocean, suspended in the waves of the

sea

great heaven of whales in the waters, old hierarchies.

And enormous mother whales lie dreaming suckling their whale-

tender young

and dreaming with strange whale eyes wide open in the waters of

the beginning and the end.

And bull-whales gather their women and whale-calves in a ring

when danger threatens, on the surface of the ceaseless flood

and range themselves like great fierce Seraphim facing the threat

encircling their huddled monsters of love.

And all this happens in the sea, in the salt

where God is also love, but without words:

and Aphrodite is the wife of whales

most happy, happy she!

and Venus among the fishes skips and is a she-dolphin

she is the gay, delighted porpoise sporting with love and the sea

she is the female tunny-fish, round and happy among the males

and dense with happy blood, dark rainbow bliss in the sea.

D.H. Lawrence poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive K-L, D.H. Lawrence, Lawrence, D.H.

Wandering At Morn

Wandering at morn,

Emerging from the night, from gloomy thoughts–thee in my thoughts,

Yearning for thee, harmonious Union! thee, Singing Bird divine!

Thee, seated coil’d in evil times, my Country, with craft and black

dismay–with every meanness, treason thrust upon thee;

–Wandering–this common marvel I beheld–the parent thrush I

watch’d, feeding its young,

(The singing thrush, whose tones of joy and faith ecstatic,

Fail not to certify and cheer my soul.)

There ponder’d, felt I,

If worms, snakes, loathsome grubs, may to sweet spiritual songs be

turn’d,

If vermin so transposed, so used, so bless’d may be, 10

Then may I trust in you, your fortunes, days, my country;

–Who knows that these may be the lessons fit for you?

From these your future Song may rise, with joyous trills,

Destin’d to fill the world.

Walt Whitman

(1819-1892)

Hans Hermans photos – Natuurdagboek 04-12

Gedicht Walt Whitman

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Hans Hermans Photos, Whitman, Walt

William Shakespeare

(1564-1616)

THE SONNETS

Sonnet 134

So now I have confessed that he is thine,

And I my self am mortgaged to thy will,

My self I’ll forfeit, so that other mine,

Thou wilt restore to be my comfort still:

But thou wilt not, nor he will not be free,

For thou art covetous, and he is kind,

He learned but surety-like to write for me,

Under that bond that him as fist doth bind.

The statute of thy beauty thou wilt take,

Thou usurer that put’st forth all to use,

And sue a friend, came debtor for my sake,

So him I lose through my unkind abuse.

Him have I lost, thou hast both him and me,

He pays the whole, and yet am I not free.

![]()

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: -Shakespeare Sonnets

![]()

Gerrit Komrij overleden

Mede namens de familie laat Uitgeverij De Bezige Bij weten dat gisteravond, na een kort ziekbed, Gerrit Komrij in Amsterdam is overleden.

We verliezen in hem een belangrijk dichter, een veelzijdig schrijver en vertaler, een groot stilist, een scherp polemist en bovenal een lieve vriend. Hij was een inspirator voor generaties dichters, schrijvers en jonge hemelbestormers, en zal dat blijven.

Gerrit Komrij (Winterswijk, 30 maart 1944) debuteerde in 1968 met de poëziebundel Maagdenburgse halve bollen en andere gedichten, die meteen de aandacht trok door de oneigentijdse vaste vorm en de grillige humor. Hij zou zijn dichterschap altijd trouw blijven. In totaal publiceerde hij zo’n vijftien bundels, verzameld onder de titel Alle gedichten tot gisteren (2004). De bundel Boemerang had hij op zijn bureau in Portugal klaargelegd om te voltooien en zal dit najaar postuum verschijnen.

Hij was een gedreven criticus en televisierecensent, stelde een aantal spraakmakende Nederlandse en Zuid-Afrikaanse bloemlezingen samen, vertaalde veel literair werk (waaronder toneelstukken van Shakespeare) en schreef toneel, essays en romans.

In 1976 was Gerrit Komrij een jaar lang een scherp televisierecensent voor NRC Handelsblad; deze spraakmakende televisiekritieken werden in 1977 gebundeld in Horen, zien en zwijgen. Als literair recensent voelde hij zich verwant aan de tijdgeest van waarheidsvinding en sarcasme. In de jaren zeventig en tachtig maakte hij vooral naam als essayist, en schuwde in dat genre geen enkel onderwerp, van het feminisme tot aan de architectuur. Zijn venijnige stijl bleek ook hier zijn belangrijkste wapen. De essays werden gebundeld in onder meer Heremijntijd (1978), Papieren tijgers (1978), Averechts (1980), Het boze oog (1983), Humeuren en temperamenten (1989), Met het bloed dat drukinkt heet (1991), Morgen heten we allemaal Ali (2010) en Kunstwonderen (2011).

In 1980 verscheen zijn eerste (autobiografische) roman, Verwoest Arcadië. Later schreef hij de romans Over de bergen (1990), Dubbelster (1993), De klopgeest (2001), Hercules (2004) en De loopjongen (2012).

Bijzonder succesvol en invloedrijk waren zijn bloemlezingen poëzie, met name De Nederlandse poëzie van de 19de en 20ste eeuw in duizend en enige gedichten (1979) en De 21ste eeuw in 185 gedichten (2010). Eigenzinnig en hilarisch is zijn bloemlezing Kakafonie. Encyclopedie van de stront (2006).

Komrij won vele prijzen, waaronder de P.C. Hooftprijs 1993 voor zijn beschouwend proza en De Gouden Uyl 1999 voor In Liefde Bloeyende. In 2000 werd hij geëerd als doctor honoris causa aan de Universiteit van Leiden.

Van 2000 tot 2004 was hij de eerste Dichter des Vaderlands, een rol die hij met grote verve vervulde.

Gerrit Komrij woonde tot 1984 in Amsterdam. Hij verhuisde in dat jaar naar Portugal, waarover hij indrukwekkend verslag deed in Vila Pouca (2008). Het boek werd genomineerd voor de Gouden Uil 2009.

Het literaire landschap is door het tomeloze plezier en de scherpzinnigheid van Gerrit Komrij decennialang in beweging gebracht. Hij heeft het mee veranderd en hij heeft het nu verlaten. ‘Van papier zijt ge en tot papier zult ge wederkeren.’ (Uit: Da Capo, Morgen heten we allemaal Ali).

ALLES BLIJFT

Daar stond een muur die ik heb aangeraakt.

De muur werd afgebroken. Van het puin

Werd verderop een fundament gemaakt.

Ik plantte een fruitboom in mijn oude tuin.

Die werd geasfalteerd. Vijf meter diep

Houdt zich een wortelstronk nog grommend koest.

Vijf eeuwen lang desnoods. De Spaanse griep

Landt ooit op Mars omdat ik heb gehoest.

Er was een vriend aan wie ik heb geschreven,

Een rots waar ik mijn naam in heb gekerfd.

Je bent een deel van alles bij je leven

En alles blijft bestaan wanneer je sterft.

(uit: Luchtspiegelingen, 2001)

Amsterdam, 6 juli 2012

Persbericht Uitgeverij De Bezige Bij

Gerrit Komrij (1944-2012)

More in: Archive K-L, In Memoriam

Marianne Moore

(1887-1972)

A Grave

Man looking into the sea,

taking the view from those who have as much right to it as

you have to it yourself,

it is human nature to stand in the middle of a thing,

but you cannot stand in the middle of this;

the sea has nothing to give but a well excavated grave.

The firs stand in a procession, each with an emerald turkey-

foot at the top,

reserved as their contours, saying nothing;

repression, however, is not the most obvious characteristic of

the sea;

the sea is a collector, quick to return a rapacious look.

There are others besides you who have worn that look —

whose expression is no longer a protest; the fish no longer

investigate them

for their bones have not lasted:

men lower nets, unconscious of the fact that they are

desecrating a grave,

and row quickly away — the blades of the oars

moving together like the feet of water-spiders as if there were

no such thing as death.

The wrinkles progress among themselves in a phalanx — beautiful

under networks of foam,

and fade breathlessly while the sea rustles in and out of the

seaweed;

the birds swim throught the air at top speed, emitting cat-calls

as heretofore —

the tortoise-shell scourges about the feet of the cliffs, in motion

beneath them;

and the ocean, under the pulsation of lighthouses and noise of

bell-buoys,

advances as usual, looking as if it were not that ocean in which

dropped things are bound to sink —

in which if they turn and twist, it is neither with volition nor

consciousness.

Marianne Moore poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive M-N

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (23)

Shoot! (Si Gira, 1926. The Notebooks of Serafino Gubbio, Cinematograph Operator by Luigi Pirandello. Translated from the Italian by C. K. Scott Moncrieff

BOOK V

1

I have just come from Aldo Nuti’s room. It is nearly one o’clock. The house–in which I am spending my first night–is asleep. It has for me a strange atmosphere, which I cannot as yet breathe with comfort; the appearance of things, the savour of life, special arrangements, traces of unfamiliar habits.

In the passage, as soon as I shut the door of Nuti’s room, holding a lighted match in my fingers, I saw close beside me, enormous on the opposite wall, my own shadow. Lost in the silence of the house, I felt my soul so small that my shadow there on the wall, grown so big, seemed to me the image of fear.

At the end of the passage, a door; outside this door, on the mat, a pair of shoes: Signorina Luisetta’s. I stopped for a moment to look at my monstrous shadow, which stretched out in the direction of this door, and the fancy came to me that the shoes were there to keep my shadow away. Suddenly, from inside the door, the old dog Piccini, who had already perhaps pricked her ears, on the alert from the first sound of a door being opened, uttered a couple of wheezy barks. It was not at the sound that she barked; but she had heard me stop in the passage for a moment; had felt my thoughts make their way into the bedroom of her young mistress, and so she barked.

Here I am in my new room. But it should not be this room. When I came here with my luggage, Cavalena, who was genuinely delighted to have me in the house, not only because of the warm affection and strong confidence which I at once inspired in him, but perhaps also because he hopes that it may be easier for him, by my influence, to find an opening in the Kosmograph, had allotted to me the other room, larger, more comfortable, better furnished.

Certainly neither he nor Signora Nene desired or ordered the change. It must be the work of Signorina Luisetta, who listened this morning in the carriage so attentively and with such dismay, as we drove away from the Kosmograph, to my summary account of Nuti’s misadventures. Yes, it must have been she, beyond question. My suspicion was confirmed a moment ago by the sight of her shoes outside the door, on the mat.

I am annoyed at the change for this reason only, that I myself, if this morning they had let me see both rooms, would have left the other to Nuti and have chosen this one for myself. Signorina Luisetta read my thoughts so clearly that without saying a word to me she has removed my things from the other room and arranged them in this. Certainly, if she had not done so, I should have been embarrassed at seeing Nuti lodged in this smaller and less comfortable of the rooms. But am I to suppose that she wished to spare me this embarrassment? I cannot. Her having done, without saying a word to me, what I would have done myself, offends me, albeit I realise that it is what had to be done, or rather precisely because I realise that it is what had to be done.

Ah, what a prodigious effect the sight of tears in a man’s eyes has on women, especially if they be tears of love. But I must be fair: they hare had a similar effect on myself.

He has kept me in there for about four hours. He wanted to go on talking and weeping: I stopped him, out of compassion chiefly for his eyes. I have never seen a pair of eyes brought to such a state by excessive weeping.

I express myself badly. Not by excessive weeping. Perhaps quite a few tears (he has shed an endless quantity), perhaps only a few tears would have been enough to bring his eyes to such a state.

And yet, it is strange! It appears that it is not he who is weeping. To judge by what he says, by what he proposes to do, he has no reason, nor, certainly, any desire to weep. The tears scald Ms eyes and cheeks, and therefore he knows that he is weeping; but he does not feel his own tears. His eyes are weeping almost for a grief that is not his, for a grief that is almost that of his tears themselves. His own grief is fierce, and refuses and scorns these tears.

But stranger still to my mind was this: that when at any point in his conversation his sentiments, so to speak, became lachrymose, his tears all at once began to slacken. While his voice grew tender and throbbed, his eyes, on the contrary, those eyes that a moment before were bloodshot and swollen with weeping, became dry and hard: fierce.

So that what he says and what his eyes say cannot correspond.

But it is there, in his eyes, and not in what he says that his heart lies. And therefore it was for his eyes chiefly that I felt compassion. Let him not talk and weep; let him weep and listen to his own weeping: it is the best thing that he can do.

There comes to me, through the wall, the sound of his step. I have advised him to go to bed, to try to sleep. He says that he cannot; that he has lost the power to sleep, for some time past. What has made him lose it? Not remorse, certainly, to judge by what he says.

Among all the phenomena of human nature one of the commonest, and at the same time one of the strangest when we study it closely, is this of the desperate, frenzied struggle which every man, however ruined by his own misdeeds, conquered and crushed in his affliction, persists in keeping up with his own conscience, in order not to acknowledge those misdeeds and not to make them a matter for remorse. That others acknowledge them and punish him for them, imprison him, inflict the cruellest tortures upon him and kill him, matters not to him; so long as he himself does not acknowledge them, but withstands his own conscience which cries them aloud at him.

Who is he? Ah, if each one of us could for an instant tear himself away from that metaphorical ideal which our countless fictions, conscious and unconscious, our fictitious interpretations of our actions and feelings lead us inevitably to form of ourselves; he would at once perceive that this ‘he’is ‘another’, another who has nothing or but very little in common with himself; and that the true ‘he’ is the one that is crying his misdeeds aloud within him; the intimate being, often doomed for the whole of our lives to remain unknown to us! We seek at all costs to preserve, to maintain in position that metaphor of ourselves, our pride and our love. And for this metaphor we undergo martyrdom and ruin ourselves, when it would be so pleasant to let ourselves succumb vanquished, to give ourselves up to our own inmost being, which is a dread deity, if we oppose ourselves to it; but becomes at once compassionate towards our every fault, as soon as we confess it, and prodigal of unexpected tendernesses. But this seems a negation of self, something unworthy of a man; and will ever be so, so long as we believe that our humanity consists in this metaphor of ourselves.

The version given by Aldo Nuti of the mishaps that have brought him low–it seems impossible!–aims above all at preserving this metaphor, his masculine vanity, which, albeit reduced before my eyes to this miserable plight, refuses nevertheless to humble itself to the confession that it has been a silly toy in the hands of a woman: a toy, a doll filled with sawdust, which the Nestoroff, after amusing herself for a while by making it open its arms and close them in an attitude of prayer, pressing with her finger the too obvious spring in its chest, flings away into a corner, breaking it in its fall.

It has risen to its feet again, this broken doll; its porcelain face and hands in a pitiful state: the hands without fingers, the face without a nose, all cracked and chipped; the spring in its chest has made a rent in the red woollen jacket and dangles out, broken; and yet, no, what is this: the doll cries out no, that it is not true that that woman made it open its arms and close them in an attitude of prayer to laugh at it, nor that, after laughing at it, she has broken it like this. It is not true!

By agreement with Duccella, by agreement with Granny Rosa he followed the affianced lovers from the villa by Sorrento to Naples, to save poor Giorgio, too innocent, and blinded by the fascination of that woman. It did not require much to save him! Enough to prove to him, to let him assure himself by experiment that the woman whom he wished to make his by marrying her, could be his, as she had been other men’s, as she would be any man’s, without any necessity of marrying her. And thereupon, challenged by poor Giorgio, he set to work to make the experiment at once. Poor Giorgio believed it to be impossible because, as might be expected, with the tactics common among women of her sort, the Nestoroff had always refused to grant him even the slightest favour, and at Capri he had seen her so contemptuous of everyone, so withdrawn and aloof! It was a horrible act of treachery. Not his action, though, but Giorgio Mirelli’s! He had promised that on receiving the proof he would at once leave the woman: instead, he killed himself.

This is the version that Aldo Nuti chooses to give of the drama.

But how, then? Was it he, the doll, that was playing the trick? And how comes he to be broken like this? If it was so easy a trick? Away with these questions, and away with all surprise. Here one must make a show of believing. Our pity must not diminish but rather increase at the overpowering necessity to lie in this poor doll, which is Aldo Nuti’s vanity: the face without a nose, the hands without fingers, the spring in the chest broken, dangling out through the rent jacket, we must allow him to lie! Only, his lies give him an excuse for weeping all the more.

They are not good tears, because he does not wish to feel his own grief in them. He does not wish them, and he despises them. He wishes to do something other than weep, and we shall have to keep him under observation. Why has he come here? He has no need to be avenged on anyone, if the treachery lay in Giorgio Mirelli’s action in killing himself and flinging his dead body between his sister and her lover. So much I said to him.

“I know,” was his answer. “But there is still she, that woman, the cause of it all! If she had not come to disturb Giorgio’s youth, to bait her hook, to spread her net for him with arts which really can be treacherous only to a novice, not because they are not treacherous in themselves, but because a man like myself, like you, recognises them at once for what they are: vipers, which we render harmless by extracting the teeth which we know to be venomous; now I should not be caught like that: I should not be caught like that! She at once saw in me an enemy, do you understand? And she tried to sting me by, stealth. From the very beginning I, on purpose, allowed her to think that it would be the easiest thing in the world for her to sting me. I wished her to shew her teeth, just so that I might draw them. And I was successful. But Giorgio, Giorgio, Giorgio had been poisoned for ever! He should have let me know that it was useless my attempting to draw the teeth of that viper….”

“Not a viper, surely!” I could not help observing. “Too much innocence for a viper, surely! To offer you her teeth so quickly, so easily…. Unless she did it to cause the death of Giorgio Mirelli.”

“Perhaps.”

“And why? If she had already succeeded in her plan of making him marry her? And did she not yield at once to your trick? Did she not let you draw her teeth before she had attained her object?”

“But she had no suspicion!”

“In that case, how in the world is she a viper? Would you have a viper not suspect? A viper would have stung after, not before! If she stung first, it means that… either she is not a viper, or for Giorgio’s sake she was willing to lose her teeth. Excuse me… no, wait a minute… please stop and listen to me… I tell you this because… I am quite of your opinion, you know… she did wish to be avenged, but at first, only at the beginning, upon Giorgio. This is my belief; I have always thought so.”

“Be avenged for what?”

“Perhaps for an insult which no woman will readily allow.”

“Woman, you say! She!”

“Yes, indeed, a woman, Signor Nuti! You who know her well, know that they are all the same, especially on this point.”

“What insult? I don’t follow you.”

“Listen: Giorgio was entirely taken up with his art, wasn’t he?”

“Yes.”

“He found at Capri this woman, who offered herself as an object of contemplation to him, to his art.”

“Precisely, yes.”

“And he did not see, he did not wish to see in her anything but her body, but only to caress it upon a canvas with his brushes, with the play of lights and colours. And then she, offended and piqued, to avenge herself, seduced him (there I agree with you!); and, having seduced him, to avenge herself further, to avenge herself still better, resisted him (am I right?) until Giorgio, blinded, in order to secure her, proposed marriage, took her to Sorrento to meet his grandmother, his sister.”

“No! It was her wish! She insisted upon it!”

“Very well, then; it was she; and I might say, insult for insult; but no, I propose now to abide by what you have said, Signor Nuti! And what you have said makes me think, that she may have insisted upon Giorgio’s taking her there, and introducing her to his grandmother and sister, expecting that Giorgio would revolt against this imposition, so that she might find an excuse for releasing herself from the obligation to marry him.”

“Release herself? Why?”

“Why, because she had already attained her object! Her vengeance was complete: Giorgio, crushed, blinded, captivated by her, by her body, to the extent of wishing to marry her! This was enough for her, and she asked for nothing more! All the rest, their wedding, life with him who would be certain to repent immediately of their marriage, would have meant unhappiness for her and for him, a chain. And perhaps she was not thinking only of herself; she may have felt some pity also for him!”

“Then you believe?”

“But you make me believe it, you make me think it, by maintaining that the woman is treacherous! To go by what you say, Signor Nuti, in a treacherous woman what she did is not consistent. A treacherous woman who desires marriage, and before her marriage gives herself to you so easily…”

“Gives herself to me?” came with a shout of rage from Aldo Nuti, driven by my arguments with his back to the wall. “Who told you that she gave herself to me? I never had her, I never had her…. Do you imagine that I can ever have thought of having her? All I required was the proof which she would not have failed to provide… a proof to shew to Giorgio!”

I was left speechless for a moment, gazing at him.

“And that viper let you have it at once? And you were able to secure it without difficulty, this proof! But then, but then, surely…”

I supposed that at last my logic had the victory so firmly in its grasp that it would no longer be possible to wrest it from me. I had yet to learn, that at the very moment when logic, striving against passion, thinks that it has secured the victory, passion with a sudden lunge snatches it back, and then with buffetings and kicks sends logic flying with all its escort of linked conclusions.

If this unfortunate man, quite obviously the dupe of this woman, for a purpose which I believe myself to have guessed, could not make her his, and has been left accordingly with this rage still in his body, after all that he has had to suffer, because that silly doll of his vanity believed honestly perhaps at first that it could easily play with a woman like the Nestoroff; what more can one say? Is it possible to induce him to go away? To force him to see that he can have no object in provoking another man, in approaching a woman who does not wish to have anything more to do with him?

Well, I have tried to induce him to go away, and have asked him what, in short, he wanted, and what he hoped from this woman.

“I don’t know, I don’t know,” he cried. “She ought to stay with me, to suffer with me. I can’t do without her any longer, I can’t be left alone any more like this. I have tried up to now, I have done everything to win Duccella over; I have made ever so many of my friends intercede for me; but I realise that it is not possible. They do not believe in my agony, in my desperation. And now I feel a need, I must cling on to some one, not be alone like this any more. You understand: I am going mad, I am going mad! I know that the woman herself is utterly worthless; but she acquires a value now from everything that I have suffered and am suffering through her. It is not love, it is hatred, it is the blood that has been shed for her! And since she has chosen to submerge my life for ever in that blood, it is necessary now that we plunge into it both together, clinging to one another, she and I, not I alone, not I alone! I cannot be left alone like this any more!”

I came away from his room without even the satisfaction of having offered him an outlet which might have relieved his heart a little. And now I can open the window and lean out to gaze at the sky, while he in the other room wrings his hands and weeps, devoured by rage and grief. If I went back now, into his room, and said to him joyfully; “I say, Signor Nuti, there are still the stars! You of course have forgotten them, but they are still there!” what would happen? To how many men, caught in the throes of a passion, or bowed down, crushed by sorrow, by hardship, would it do good to think that there, above the roof, is the sky, and that in the sky there are the stars. Even if the fact of the stars’ being there did not inspire in them any religious consolation. As we gaze at them, our own feeble pettiness is engulfed, vanishes in the emptiness of space, and every reason for our torment must seem to us meagre and vain. But we must have in ourselves, in the moment of passion, the capacity to think of the stars. This may be found in a man like myself, who for some time past has looked at everything, himself included, from a distance. If I were to go in there and tell Signor Nuti that the stars were shining in the sky, he would perhaps shout back at me to give them his kind regards, and would turn me out of the room like a dog.

But can I now, as Polacco would like, constitute myself his guardian? I can imagine how Carlo Ferro will glare at me presently, on seeing me come to the Kosmograph with him by my side. And God knows that I have no more reason to be a friend of one than of the other.

All I ask is to continue, with my usual impassivity, my work as an operator. I shall not look out of the window. Alas, since that cursed Senator Zeme has been to the Kosmograph, I see even in the sky a ‘marvel’ of cinematography.

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (23)

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: -Shoot!, Archive O-P, Pirandello, Luigi, Pirandello, Luigi

Theodor Fontane

(1819–1898)

Einem Todten

Zwei Jahre kaum, als heitre Träume scheuchten

Der Sorgen dunklen Schwarm aus Deiner Brust;

Du riefst: „Ade!“ ich sah Dein Auge leuchten,

Und fühlte Thränen doch das meine feuchten,

Ich war der ew’gen Trennung mir bewußt.

Mein armer Wilm, das Roth auf Deinen Wangen,

Es war das Kleid des frischen Lebens nicht,

Der Tod nur, sichrer Dich in’s Netz zu fangen,

Ließ Rosen blühn auf Deinem Angesicht.

Du sahst das Roß des Matadors sich bäumen,

Eh’ Deine Barke noch vom Ufer stieß, –

Gen Spanien ging’s, – Du durftest heiter träumen

Von duft’gen Mandel- und Kastanienbäumen,

Denn Deine Zukunft barg ein Paradies.

Doch statt vom Duft der Blüthen zu gesunden,

Hat Dich der Hauch des Todes angeweht,

Und ach, der Matador, den Du gefunden,

Als Sensenmann vor meiner Seele steht.

Ich sah ihn längst Dich Schritt vor Schritt bewachen,

Gleich einem Schatten Dir zur Seite gehn,

Behende sprang er mit Dir in den Nachen,

Und immer schien er höhnisch mir zu lachen,

So oft du riefst: „auf fröhlich Wiedersehn!“

Auf Wiedersehn! wann, Freund? statt Herzensfrieden

Hat ew’ge Ruh die Ferne Dir geschenkt,

Und in die Gruft, die Deinem Schmerz beschieden

Hat man Dich selber nun hinabgesenkt.

Schön ist das Leben! ach, man lernt es lieben

Recht innig erst, wenn man es meiden soll,

Doch in die weite Welt hinaus getrieben,

Wo fremd wie wir auch unser Herz geblieben,

Da wird der Tod uns doppelt qualenvoll.

Auf welcher Wange sahst Du Thränen glänzen?

Wer hat Dein brechend Auge zugedrückt?

Mein armer Wilm, mit Immortellenkränzen

Hat flücht’ges Mitleid nur Dein Grab geschmückt.

Was half es Dir, daß schöner dort die Rosen,

Und goldner selbst des Himmels Sterne glühn?

Nun gilt es gleich – ob rauhe Stürme tosen,

Ob linde Weste mit den Blumen kosen,

Mit Blumen, Freund, die Deinem Grab entblühn.

Du ruhtest besser wohl am heim’schen Strande,

Im Dünensand, wo Du zu ruhn geglaubt:

Ein Kuß der Liebe hätt’ im Vaterlande

Dem Tode seinen Stachel noch geraubt.

Doch jetzt, wo du den bittren Kampf bestanden,

Jetzt ruf ich: „Freund, wohl Dir! es ist vorbei.“

Schön ist das Leben, doch von tausend Banden,

Ob in der Heimath, ob in fremden Landen,

Macht erst der Tod die Menschenseele frei.

Mir löst die Pflicht, der strenge Kerkermeister,

Die Fessel nie, gleichviel ob Tag ob Nacht,

Und selbst von Deinem Grabeshügel reißt er

Mich unerbittlich, wenn der Tag erwacht.

Wilhelm Krause starb zu Malaga 1842.

Theodor Fontane poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive E-F, Theodor Fontane

Tristan Tzara

(1896-1963)

To Make A Dadaist Poem

Take a newspaper.

Take some scissors.

Choose from this paper an article the length you want to make your poem.

Cut out the article.

Next carefully cut out each of the words that make up this article and put them all in a bag.

Shake gently.

Next take out each cutting one after the other.

Copy conscientiously in the order in which they left the bag.

The poem will resemble you.

And there you are–an infinitely original author of charming sensibility, even though unappreciated by the vulgar herd.

Tristan Tzara poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Dada, Tzara, Tristan

D. H. Lawrence

(1885-1930)

Last Words to Miriam

Yours is the shame and sorrow

But the disgrace is mine;

Your love was dark and thorough,

Mine was the love of the sun for a flower

He creates with his shine.

I was diligent to explore you,

Blossom you stalk by stalk,

Till my fire of creation bore you

Shrivelling down in the final dour

Anguish—then I suffered a balk.

I knew your pain, and it broke

My fine, craftsman’s nerve;

Your body quailed at my stroke,

And my courage failed to give you the last

Fine torture you did deserve.

You are shapely, you are adorned,

But opaque and dull in the flesh,

Who, had I but pierced with the thorned

Fire-threshing anguish, were fused and cast

In a lovely illumined mesh.

Like a painted window: the best

Suffering burnt through your flesh,

Undressed it and left it blest

With a quivering sweet wisdom of grace: but now

Who shall take you afresh?

Now who will burn you free,

From your body’s terrors and dross,

Since the fire has failed in me?

What man will stoop in your flesh to plough

The shrieking cross?

A mute, nearly beautiful thing

Is your face, that fills me with shame

As I see it hardening,

Warping the perfect image of God,

And darkening my eternal fame.

D.H. Lawrence poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive K-L, D.H. Lawrence, Lawrence, D.H.

William Shakespeare

(1564-1616)

THE SONNETS

Sonnet 133

Beshrew that heart that makes my heart to groan

For that deep wound it gives my friend and me;

Is’t not enough to torture me alone,

But slave to slavery my sweet’st friend must be?

Me from my self thy cruel eye hath taken,

And my next self thou harder hast engrossed,

Of him, my self, and thee I am forsaken,

A torment thrice three-fold thus to be crossed:

Prison my heart in thy steel bosom’s ward,

But then my friend’s heart let my poor heart bail,

Whoe’er keeps me, let my heart be his guard,

Thou canst not then use rigour in my gaol.

And yet thou wilt, for I being pent in thee,

Perforce am thine and all that is in me.

![]()

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: -Shakespeare Sonnets

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature