Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

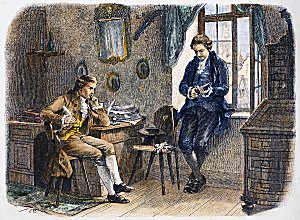

The Sorrows of Young Werther (17)

by J.W. von Goethe

JULY 8.

What a child is man that he should be so solicitous about a look! What a child is man! We had been to Walheim: the ladies went in a carriage; but during our walk I thought I saw in Charlotte’s dark eyes–I am a fool–but forgive me! you should see them,–those eyes.–However, to be brief (for my own eyes are weighed down with sleep), you must know, when the ladies stepped into their carriage again, young W. Seldstadt, Andran, and I were standing about the door. They are a merry set of fellows, and they were all laughing and joking together. I watched Charlotte’s eyes. They wandered from one to the other; but they did not light on me, on me, who stood there motionless, and who saw nothing but her! My heart bade her a thousand times adieu, but she noticed me not.

The carriage drove off; and my eyes filled with tears. I looked after her: suddenly I saw Charlotte’s bonnet leaning out of the window, and she turned to look back, was it at me? My dear friend, I know not; and in this uncertainty I find consolation. Perhaps she turned to look at me. Perhaps! Good-night–what a child I am!

JULY 10.

You should see how foolish I look in company when her name is mentioned, particularly when I am asked plainly how I like her. How I like her!

I detest the phrase. What sort of creature must he be who merely liked Charlotte, whose whole heart and senses were not entirely absorbed by her. Like her! Some one asked me lately how I liked Ossian.

The Sorrows of Young Werther (Die Leiden des jungen Werther) by J.W. von Goethe. Translated by R.D. Boylan.

To be continued

fleursdumal.nl magazine for art & literature

More in: -Die Leiden des jungen Werther, Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von

Stefan Georg

(1868-1933)

STRAND

O lenken wir hinweg von wellenauen!

Die wenn auch wild im wollen und mit düsterm rollen

Nur dulden scheuer möwen schwingenschlag

Und stet des keuschen himmels farben schauen.

Wir heuchelten zu lang schon vor dem tag.

Zu weihern grün mit moor und blumenspuren

Wo gras und laub und ranken wirr und üppig schwanken

Und ewger abend einen altar weiht!

Die schwäne die da aus der buchtung fuhren ·

Geheimnisreich · sind unser brautgeleit.

Die lust entführt uns aus dem fahlen norden:

Wo deine lippen glühen fremde kelche blühen –

Und fliesst dein leib dahin wie blütenschnee

Dann rauschen alle stauden in akkorden

Und werden lorbeer tee und aloe.

Stefan Georg poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive G-H, George, Stefan

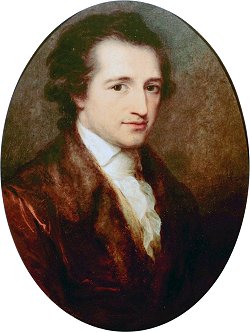

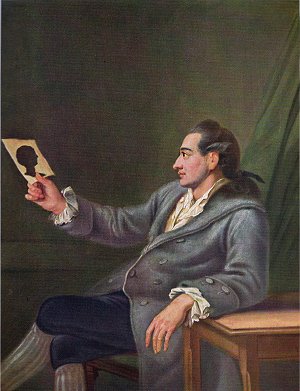

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

(1749-1832)

Liebhaber in allen Gestalten

Ich wollt, ich wär ein Fisch,

So hurtig und frisch;

Und kämst du zu anglen,

Ich würde nicht manglen.

Ich wollt, ich wär ein Fisch,

So hurtig und frisch.

Ich wollt, ich wär ein Pferd,

Da wär ich dir wert.

O wär ich ein Wagen,

Bequem dich zu tragen.

Ich wollt, ich wär ein Pferd,

Da wär ich dir wert.

Ich wollt, ich wäre Gold,

Dir immer im Sold;

Und tätst du was kaufen,

Käm ich wieder gelaufen.

Ich wollt, ich wäre Gold,

Dir immer im Sold.

Ich wollt, ich wär treu,

Mein Liebchen stets neu;

Ich wollt mich verheißen,

Wollt nimmer verreisen.

Ich wollt, ich wär treu,

Mein Liebchen stets neu.

Ich wollt, ich wär alt

Und runzlig und kalt;

Tätst du mir’s versagen,

Da könnt mich’s nicht plagen.

Ich wollt, ich wär alt

Und runzlig und kalt.

Wär ich Affe sogleich,

Voll neckender Streich’;

Hätt was dich verdrossen,

So macht ich dir Possen.

Wär ich Affe sogleich,

Voll neckender Streich’.

Wär ich gut wie ein Schaf,

Wie der Löwe so brav;

Hätt Augen wie’s Lüchschen

Und Listen wie’s Füchschen.

Wär ich gut wie ein Schaf,

Wie der Löwe so brav.

Was alles ich wär,

Das gönnt ich dir sehr;

Mit fürstlichen Gaben,

Du solltest mich haben.

Was alles ich wär,

Das gönnt ich dir sehr.

Doch bin ich, wie ich bin,

Und nimm mich nur hin!

Willst du beßre besitzen,

So laß dir sie schnitzen.

Ich bin nun, wie ich bin;

So nimm mich nur hin!

Goethe poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive G-H, Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von

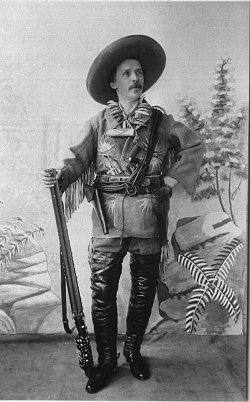

Karl May

(1842-1912)

Trost

Horch, klopfte es nicht an die Pforte?

Wer naht, von Himmelsduft umrauscht?

Woher des Trostes süße Worte,

Auf die mein Herz voll Andacht lauscht?

Wer neigt, wenn alle Sterne sanken,

Mit mildem Licht und stiller Huld

Sich zu dem Staub- und Erdenkranken?

Es ist der Engel der Geduld.

»O laß den Gram nicht mächtig werden,

Du tiefbetrübtes Menschenkind!

Wiß’, daß die Leiden dieser Erden

Des Himmels beste Gaben sind

Und daß, wenn Sorgen Dich umwogen

Und Dich umhüllt des Zweifels Nacht,

Dort an dem glanzumfloss’nen Bogen

Ein treues Vaterauge wacht!«

»O laß Dir nicht zu Herzen steigen

Die langverhaltne Thränenfluth!

Wiß, daß grad in den schmerzensreichen

Geschicken tiefe Weisheit ruht,

Und daß, wenn sonst Dir Nichts verbliebe,

Die Hoffnung doch Dir immer lacht,

Da über Dich in ew’ger Liebe

Ein treues Vaterauge wacht!«

»O wolle nie Dich einsam fühlen!

Obgleich kein Aug’ sie wandeln sah,

Die sorgenheiße Stirn zu kühlen

Sind Himmelsboten immer da.

Wer gern dem eignen Herzen glaubte,

Der kennt des Pulses heilige Macht.

Drum wiß, das über Deinem Haupte

Ein treues Vaterauge wacht!«

»Drum füge Dich in Gottes Walten

Und trag Dein Leid getrost und still.

Es muß im Dunkel sich gestalten,

Was er zum Lichte führen will.

Dann bringt der Glaube reichen Segen,

Ob ihn der Zweifler auch verlacht,

Daß über allen Deinen Wegen

Ein treues Vaterauge wacht!«

Karl May poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive M-N, Karl May

The Sorrows of Young Werther (16)

by J.W. von Goethe

JULY 6.

She is still with her dying friend, and is still the same bright, beautiful creature whose presence softens pain, and sheds happiness around whichever way she turns. She went out yesterday with her little sisters: I knew it, and went to meet them; and we walked together. In about an hour and a half we returned to the town. We stopped at the spring I am so fond of, and which is now a thousand times dearer to me than ever. Charlotte seated herself upon the low wall, and we gathered about her. I looked around, and recalled the time when my heart was unoccupied and free. “Dear fountain!” I said, “since that time I have no more come to enjoy cool repose by thy fresh stream: I have passed thee with careless steps, and scarcely bestowed a glance upon thee.” I looked down, and observed Charlotte’s little sister, Jane, coming up the steps with a glass of water. I turned toward Charlotte, and I felt her influence over me. Jane at the moment approached with the glass. Her sister, Marianne, wished to take it from her. “No!” cried the child, with the sweetest expression of face, “Charlotte must drink first.”

The affection and simplicity with which this was uttered so charmed me, that I sought to express my feelings by catching up the child and kissing her heartily. She was frightened, and began to cry. “You should not do that,” said Charlotte: I felt perplexed. “Come, Jane,” she continued, taking her hand, and leading her down the steps again, “it is no matter: wash yourself quickly in the fresh water.” I stood and watched them; and when I saw the little dear rubbing her cheeks with her wet hands, in full belief that all the impurities contracted from my ugly beard would be washed off by the miraculous water, and how, though Charlotte said it would do, she continued still to wash with all her might, as though she thought too much were better than too little, I assure you, Wilhelm, I never attended a baptism with greater reverence; and, when Charlotte came up from the well, I could have prostrated myself as before the prophet of an Eastern nation.

In the evening I would not resist telling the story to a person who, I thought, possessed some natural feeling, because he was a man of understanding. But what a mistake I made. He maintained it was very wrong of Charlotte, that we should not deceive children, that such things occasioned countless mistakes and superstitions, from which we were bound to protect the young. It occurred to me then, that this very man had been baptised only a week before; so I said nothing further, but maintained the justice of my own convictions. We should deal with children as God deals with us, we are happiest under the influence of innocent delusions.

The Sorrows of Young Werther (Die Leiden des jungen Werther) by J.W. von Goethe. Translated by R.D. Boylan.

To be continued

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: -Die Leiden des jungen Werther, Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von

Kate Tempest: Brand New Ancients On Film – Part 2

In association with the Brand New Ancients tour, Battersea Arts Centre in collaboration with director Joe Roberts, has produced three short films interpreting Kate Tempest’s spoken word through moving image.

Kate Tempest started out when she was 16, rapping at strangers on night busses and pestering mc’s to let her on the mic at raves. Ten years later she is a published playwright, poet and respected recording artist.

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Art & Literature News, AUDIO, CINEMA, RADIO & TV, Kate/Kae Tempest, Tempest, Kate/Kae

IJzerhard

Stalen glans op paars blad. Op hoge stelen wiegt

de ijzerhard. Middaguur in onze hortus botanicus

liegt niet: het land van gisteren is toe. Alles bloeit.

Ik hoor kinderen op een nabijgelegen schoolplein

driewerf hoera roepen. Er wordt traag gesproeid

door een man die graag bezorgd lijkt. Soms wil hij

de tuin uit hollen en het op een gillen zetten, maar

zijn bladeren houden niet van geluid. Het ruikt naar

zoethout. Een koolwitje laveert tegen wind in, en zand

wijkt zachtjes voor zaad. Wolkjes zijn licht en de goden

nabij. Laat alle mensen maar weten waar de verhalen

over gaan. Wie een grens trekt heeft een huis.

Bert Bevers

verschenen in Eigen terrein – Gedichten 1998-2013, Uitgeverij WEL, Bergen op Zoom, 2013

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Bevers, Bert

Friedrich Hebbel

(1813-1863)

Knabentod

Vom Berg, der Knab’,

Der zieht hinab

In heißen Sommertagen;

Im Tannenwald,

Da macht er Halt,

Er kann sich kaum noch tragen.

Den wilden Bach,

Er sieht ihn jach

In’s Thal herunter schäumen;

Ihn dürstet sehr,

Nun noch viel mehr:

Nur hin! Wer würde säumen!

Da ist die Flut!

O, in der Glut,

Was kann so köstlich blinken!

Er schöpft und trinkt,

Er stürzt und sinkt

Und trinkt noch im Versinken!

Das Lied ist aus,

Und macht’s dir Graus:

Wer wird’s im Winter singen!

Zur Sommerzeit

Bist du bereit,

Dem Knaben nachzuspringen.

Friedrich Hebbel poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive G-H, CLASSIC POETRY

The Sorrows of Young Werther (15)

by J.W. von Goethe

JULY 1.

The consolation Charlotte can bring to an invalid I experience from my own heart, which suffers more from her absence than many a poor creature lingering on a bed of sickness. She is gone to spend a few days in the town with a very worthy woman, who is given over by the physicians, and wishes to have Charlotte near her in her last moments. I accompanied her last week on a visit to the Vicar of S–, a small village in the mountains, about a league hence. We arrived about four o’clock: Charlotte had taken her little sister with her. When we entered the vicarage court, we found the good old man sitting on a bench before the door, under the shade of two large walnut-trees. At the sight of Charlotte he seemed to gain new life, rose, forgot his stick, and ventured to walk toward her. She ran to him, and made him sit down again; then, placing herself by his side, she gave him a number of messages from her father, and then caught up his youngest child, a dirty, ugly little thing, the joy of his old age, and kissed it. I wish you could have witnessed her attention to this old man,–how she raised her voice on account of his deafness; how she told him of healthy young people, who had been carried off when it was least expected; praised the virtues of Carlsbad, and commended his determination to spend the ensuing summer there; and assured him that he looked better and stronger than he did when she saw him last. I, in the meantime, paid attention to his good lady. The old man seemed quite in spirits; and as I could not help admiring the beauty of the walnut-trees, which formed such an agreeable shade over our heads, he began, though with some little difficulty, to tell us their history. “As to the oldest,” said he, “we do not know who planted it,–some say one clergyman, and some another: but the younger one, there behind us, is exactly the age of my wife, fifty years old next October; her father planted it in the morning, and in the evening she came into the world. My wife’s father was my predecessor here, and I cannot tell you how fond he was of that tree; and it is fully as dear to me. Under the shade of that very tree, upon a log of wood, my wife was seated knitting, when I, a poor student, came into this court for the first time, just seven and twenty years ago.”

Charlotte inquired for his daughter. He said she was gone with Herr Schmidt to the meadows, and was with the haymakers. The old man then resumed his story, and told us how his predecessor had taken a fancy to him, as had his daughter likewise; and how he had become first his curate, and subsequently his successor. He had scarcely finished his story when his daughter returned through the garden, accompanied by the above-mentioned Herr Schmidt. She welcomed Charlotte affectionately, and I confess I was much taken with her appearance. She was a lively-looking, good-humoured brunette, quite competent to amuse one for a short time in the country. Her lover (for such Herr Schmidt evidently appeared to be) was a polite, reserved personage, and would not join our conversation, notwithstanding all Charlotte’s endeavours to draw him out. I was much annoyed at observing, by his countenance, that his silence did not arise from want of talent, but from caprice and ill-humour. This subsequently became very evident, when we set out to take a walk, and Frederica joining Charlotte, with whom I was talking, the worthy gentleman’s face, which was naturally rather sombre, became so dark and angry that Charlotte was obliged to touch my arm, and remind me that I was talking too much to Frederica. Nothing distresses me more than to see men torment each other; particularly when in the flower of their age, in the very season of pleasure, they waste their few short days of sunshine in quarrels and disputes, and only perceive their error when it is too late to repair it. This thought dwelt upon my mind; and in the evening, when we returned to the vicar’s, and were sitting round the table with our bread end milk, the conversation turned on the joys and sorrows of the world, I could not resist the temptation to inveigh bitterly against ill-humour. “We are apt,” said I, “to complain, but–with very little cause, that our happy days are few, and our evil days many. If our hearts were always disposed to receive the benefits Heaven sends us, we should acquire strength to support evil when it comes.” “But,” observed the vicar’s wife, “we cannot always command our tempers, so much depends upon the constitution: when the body suffers, the mind is ill at ease.” “I acknowledge that,” I continued; “but we must consider such a disposition in the light of a disease, and inquire whether there is no remedy for it.”

“I should be glad to hear one,” said Charlotte: “at least, I think very much depends upon ourselves; I know it is so with me. When anything annoys me, and disturbs my temper, I hasten into the garden, hum a couple of country dances, and it is all right with me directly.” “That is what I meant,” I replied; “ill-humour resembles indolence: it is natural to us; but if once we have courage to exert ourselves, we find our work run fresh from our hands, and we experience in the activity from which we shrank a real enjoyment.” Frederica listened very attentively: and the young man objected, that we were not masters of ourselves, and still less so of our feelings. “The question is about a disagreeable feeling,” I added, “from which every one would willingly escape, but none know their own power without trial. Invalids are glad to consult physicians, and submit to the most scrupulous regimen, the most nauseous medicines, in order to recover their health.” I observed that the good old man inclined his head, and exerted himself to hear our discourse; so I raised my voice, and addressed myself directly to him. “We preach against a great many crimes,” I observed, “but I never remember a sermon delivered against ill-humour.” “That may do very well for your town clergymen,” said he: “country people are never ill-humoured; though, indeed, it might be useful, occasionally, to my wife for instance, and the judge.” We all laughed, as did he likewise very cordially, till he fell into a fit of coughing, which interrupted our conversation for a time. Herr Schmidt resumed the subject. “You call ill humour a crime,” he remarked, “but I think you use too strong a term.” “Not at all,” I replied, “if that deserves the name which is so pernicious to ourselves and our neighbours. Is it not enough that we want the power to make one another happy, must we deprive each other of the pleasure which we can all make for ourselves? Show me the man who has the courage to hide his ill-humour, who bears the whole burden himself, without disturbing the peace of those around him. No: ill-humour arises from an inward consciousness of our own want of merit, from a discontent which ever accompanies that envy which foolish vanity engenders. We see people happy, whom we have not made so, and cannot endure the sight.” Charlotte looked at me with a smile; she observed the emotion with which I spoke: and a tear in the eyes of Frederica stimulated me to proceed. “Woe unto those,” I said, “who use their power over a human heart to destroy the simple pleasures it would naturally enjoy! All the favours, all the attentions, in the world cannot compensate for the loss of that happiness which a cruel tyranny has destroyed.” My heart was full as I spoke. A recollection of many things which had happened pressed upon my mind, and filled my eyes with tears.

“We should daily repeat to ourselves,” I exclaimed, “that we should not interfere with our friends, unless to leave them in possession of their own joys, and increase their happiness by sharing it with them! But when their souls are tormented by a violent passion, or their hearts rent with grief, is it in your power to afford them the slightest consolation?

“And when the last fatal malady seizes the being whose untimely grave you have prepared, when she lies languid and exhausted before you, her dim eyes raised to heaven, and the damp of death upon her pallid brow, there you stand at her bedside like a condemned criminal, with the bitter feeling that your whole fortune could not save her; and the agonising thought wrings you, that all your efforts are powerless to impart even a moment’s strength to the departing soul, or quicken her with a transitory consolation.”

At these words the remembrance of a similar scene at which I had been once present fell with full force upon my heart. I buried my face in my handkerchief, and hastened from the room, and was only recalled to my recollection by Charlotte’s voice, who reminded me that it was time to return home. With what tenderness she chid me on the way for the too eager interest I took in everything! She declared it would do me injury, and that I ought to spare myself. Yes, my angel! I will do so for your sake.

The Sorrows of Young Werther (Die Leiden des jungen Werther) by J.W. von Goethe. Translated by R.D. Boylan.

To be continued

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: -Die Leiden des jungen Werther, Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von

Rob Stuart: Entropy

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: *Concrete + Visual Poetry P-T, Rob Stuart, Rob Stuart, Stuart, Rob

Théophile Gautier

(1811-1872)

A deux beaux yeux

Vous avez un regard singulier et charmant ;

Comme la lune au fond du lac qui la reflète,

Votre prunelle, où brille une humide paillette,

Au coin de vos doux yeux roule languissamment ;

Ils semblent avoir pris ses feux au diamant ;

Ils sont de plus belle eau qu’une perle parfaite,

Et vos grands cils émus, de leur aile inquiète,

Ne voilent qu’à demi leur vif rayonnement.

Mille petits amours, à leur miroir de flamme,

Se viennent regarder et s’y trouvent plus beaux,

Et les désirs y vont rallumer leurs flambeaux.

Ils sont si transparents, qu’ils laissent voir votre âme,

Comme une fleur céleste au calice idéal

Que l’on apercevrait à travers un cristal.

Théophile Gautier poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive G-H, Gautier, Théophile

Passer domesticus

Zijn schroomvol hopen op een kleine holte

onder schuine dakpannen vergt steeds meer

tijd. Hij hunkert naar nabijheid van toonloos

dorre struiken, naar van kreupelhout de lege

grijste. Het vaakst zie ik hem nog in de Zoo.

Daar kronkelt in hoekjes hout dat hij graag

heeft, wordt hij door papegaaien bij het eten

in hun kooien als een kleine broer aanvaard.

Slapen zie ik hem nooit. Om het stoere snaveltje

glanst constant een vogeltjesglimlach. Hij hupt

en roetsjt met graagte in de buurt. Hij wil meer.

Hij wil u wel nabij zijn maar toch niet al te zeer.

Bert Bevers

eerder verschenen in Eigen terrein – Gedichten 1998-2013, Uitgeverij WEL, Bergen op Zoom, 2013

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Bevers, Bert, MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY - department of ravens & crows, birds of prey, riding a zebra, spring, summer, autumn, winter

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature