Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

Oscar Wilde

Oscar Wilde

(1854 – 1900)

The Teacher of Wisdom

From his childhood he had been as one filled with the perfect knowledge of God, and even while he was yet but a lad many of the saints, as well as certain holy women who dwelt in the free city of his birth, had been stirred to much wonder by the grave wisdom of his answers.

And when his parents had given him the robe and the ring of manhood he kissed them, and left them and went out into the world, that he might speak to the world about God. For there were at that time many in the world who either knew not God at all, or had but an incomplete knowledge of Him, or worshipped the false gods who dwell in groves and have no care of their worshippers.

And he set his face to the sun and journeyed, walking without sandals, as he had seen the saints walk, and carrying at his girdle a leathern wallet and a little water-bottle of burnt clay.

And as he walked along the highway he was full of the joy that comes from the perfect knowledge of God, and he sang praises unto God without ceasing; and after a time he reached a strange land in which there were many cities.

And he passed through eleven cities. And some of these cities were in valleys, and others were by the banks of great rivers, and others were set on hills. And in each city he found a disciple who loved him and followed him, and a great multitude also of people followed him from each city, and the knowledge of God spread in the whole land, and many of the rulers were converted, and the priests of the temples in which there were idols found that half of their gain was gone, and when they beat upon their drums at noon none, or but a few, came with peacocks and with offerings of flesh as had been the custom of the land before his coming.

Yet the more the people followed him, and the greater the number of his disciples, the greater became his sorrow. And he knew not why his sorrow was so great. For he spake ever about God, and out of the fulness of that perfect knowledge of God which God had Himself given to him.

And one evening he passed out of the eleventh city, which was a city of Armenia, and his disciples and a great crowd of people followed after him; and he went up on to a mountain and sat down on a rock that was on the mountain, and his disciples stood round him, and the multitude knelt in the valley.

And he bowed his head on his hands and wept, and said to his Soul, ‘Why is it that I am full of sorrow and fear, and that each of my disciples is as an enemy that walks in the noonday?’

And his Soul answered him and said, ‘God filled thee with the perfect knowledge of Himself, and thou hast given this knowledge away to others. The pearl of great price thou hast divided, and the vesture without seam thou hast parted asunder. He who giveth away wisdom robbeth himself. He is as one who giveth his treasure to a robber. Is not God wiser than thou art? Who art thou to give away the secret that God hath told thee? I was rich once, and thou hast made me poor. Once I saw God, and now thou hast hidden Him from me.’

And he wept again, for he knew that his Soul spake truth to him, and that he had given to others the perfect knowledge of God, and that he was as one clinging to the skirts of God, and that his faith was leaving him by reason of the number of those who believed in him.

And he said to himself, ‘I will talk no more about God. He who giveth away wisdom robbeth himself’

And after the space of some hours his disciples came near him and bowed themselves to the ground and said, ‘Master, talk to us about God, for thou hast the perfect knowledge of God, and no man save thee hath this knowledge.’

And he answered them and said, ‘I will talk to you about all other things that are in heaven and on earth, but about God I will not talk to you. Neither now, nor at any time, will I talk to you about God.’

And they were wroth with him and said to him, ‘Thou hast led us into the desert that we might hearken to thee. Wilt thou send us away hungry, and the great multitude that thou hast made to follow thee?’

And he answered them and said, ‘I will not talk to you about God.’

And the multitude murmured against him and said to him ‘Thou hast led us into the desert, and hast given us no food to eat. Talk to us about God and it will suffice us.’

But he answered them not a word. For he knew that if he spake to them about God he would give away his treasure.

And his disciples went away sadly, and the multitude of people returned to their own homes. And many died on the way.

And when he was alone he rose up and set his face to the moon, and journeyed for seven moons, speaking to no man nor making any answer. And when the seventh moon had waned he reached that desert which is the desert of the Great River. And having found a cavern in which a Centaur had once dwelt, he took it for his place of dwelling, and made himself a mat of reeds on which to lie, and became a hermit. And every hour the Hermit praised God that He had suffered him to keep some knowledge of Him and of His wonderful greatness.

Now, one evening, as the Hermit was seated before the cavern in which he had made his place of dwelling, he beheld a young man of evil and beautiful face who passed by in mean apparel and with empty hands. Every evening with empty hands the young man passed by, and every morning he returned with his hands full of purple and pearls. For he was a Robber and robbed the caravans of the merchants.

And the Hermit looked at him and pitied him. But he spake not a word. For he knew that he who speaks a word loses his faith.

And one morning, as the young man returned with his hands full of purple and pearls, he stopped and frowned and stamped his foot upon the sand, and said to the Hermit: ‘Why do you look at me ever in this manner as I pass by? What is it that I see in your eyes? For no man has looked at me before in this manner. And the thing is a thorn and a trouble to me.’

And the Hermit answered him and said, ‘What you see in my eyes is pity. Pity is what looks out at you from my eyes.’

And the young man laughed with scorn, and cried to the Hermit in a bitter voice, and said to him, ‘I have purple and pearls in my hands, and you have but a mat of reeds on which to lie. What pity should you have for me? And for what reason have you this pity?’

‘I have pity for you,’ said the Hermit, ‘because you have no knowledge of God.’

‘Is this knowledge of God a precious thing?’ asked the young man, and he came close to the mouth of the cavern.

‘It is more precious than all the purple and the pearls of the world,’ answered the Hermit.

‘And have you got it?’ said the young Robber, and he came closer still.

‘Once, indeed,’ answered the Hermit, ‘I possessed the perfect knowledge of God. But in my foolishness I parted with it, and divided it amongst others. Yet even now is such knowledge as remains to me more precious than purple or pearls.’

And when the young Robber heard this he threw away the purple and the pearls that he was bearing in his hands, and drawing a sharp sword of curved steel he said to the Hermit, ‘Give me, forthwith, this knowledge of God that you possess, or I will surely slay you. Wherefore should I not slay him who has a treasure greater than my treasure?’

And the Hermit spread out his arms and said, ‘Were it not better for me to go unto the uttermost courts of God and praise Him, than to live in the world and have no knowledge of Him? Slay me if that be your desire. But I will not give away my knowledge of God.’

And the young Robber knelt down and besought him, but the Hermit would not talk to him about God, nor give him his Treasure, and the young Robber rose up and said to the Hermit, ‘Be it as you will. As for myself, I will go to the City of the Seven Sins, that is but three days’ journey from this place, and for my purple they will give me pleasure, and for my pearls they will sell me joy.’ And he took up the purple and the pearls and went swiftly away.

And the Hermit cried out and followed him and besought him. For the space of three days he followed the young Robber on the road and entreated him to return, nor to enter into the City of the Seven Sins.

And ever and anon the young Robber looked back at the Hermit and called to him, and said, ‘Will you give me this knowledge of God which is more precious than purple and pearls? If you will give me that, I will not enter the city.’

And ever did the Hermit answer, ‘All things that I have I will give thee, save that one thing only. For that thing it is not lawful for me to give away.

And in the twilight of the third day they came nigh to the great scarlet gates of the City of the Seven Sins. And from the city there came the sound of much laughter.

And the young Robber laughed in answer, and sought to knock at the gate. And as he did so the Hermit ran forward and caught him by the skirts of his raiment, and said to him: ‘Stretch forth your hands, and set your arms around my neck, and put your ear close to my lips, and I will give you what remains to me of the knowledge of God.’ And the young Robber stopped.

And when the Hermit had given away his knowledge of God, he fell upon the ground and wept, and a great darkness hid him from the city and the young Robber, so that he saw them no more.

And as he lay there weeping he was ware of One who was standing beside him; and He who was standing beside him had feet of brass and hair like fine wool. And He raised the Hermit up, and said to him: ‘Before this time thou hadst the perfect knowledge of God. Now thou shalt have the perfect love of God. Wherefore art thou weeping?’ And He kissed him.

Oscar Wilde, 1894

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive W-X, Wilde, Oscar, Wilde, Oscar

Tristan Corbière

Feminin singulier

Éternel Féminin de l’éternel Jocrisse!

Fais-nous sauter, pantins nous payons les décors!

Nous éclairons la rampe…. Et toi, dans la coulisse,

Tu peux faire au pompier le pur don de ton corps.

Fais claquer sur nos dos le fouet de ton caprice,

Couronne tes genoux!… et nos têtes dix-cors;

Ris! montre tes dents! mais … nous avons la police,

Et quelque chose en nous d’eunuque et de recors.

… Ah tu ne comprends pas?…–Moi non plus–Fais la belle

Tourne: nous sommes soûls! Et plats: Fais la cruelle!

Cravache ton pacha, ton humble serviteur!…

Après, sache tomber!–mais tomber avec grâce–

Sur notre sable fin ne laisse pas de trace!…

–C’est le métier de femme et de gladiateur.–

Tristan Corbière (1845 – 1875)

Feminin singulier

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: *Archive Les Poètes Maudits, Archive C-D, Corbière, Tristan

Anne Finch

To A Husband

This is to the crown and blessing of my life,

The much loved husband of a happy wife;

To him whose constant passion found the art

To win a stubborn and ungrateful heart,

And to the world by tenderest proof discovers

They err, who say that husbands can’t be lovers.

With such return of passion, as is due,

Daphnis I love, Daphinis my thoughts pursue;

Daphnis, my hopes and joys are bounded all in you.

Even I, for Daphnis’ and my promise’ sake,

What I in woman censure, undertake.

But this from love, not vanity proceeds;

You know who writes, and I who ’tis that reads.

Judge not my passion by my want of skill:

Many love well, though they express it ill;

And I your censure could with pleasure bear,

Would you but soon return, and speak it here.

Anne Finch (1661 – 1720)

To A Husband

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive E-F, CLASSIC POETRY

Samuel Taylor Coleridge

Xanadu – Kubla Khan

In Xanadu did Kubla Khan

A stately pleasure-dome decree:

Where Alph, the sacred river, ran

Through caverns measureless to man

Down to a sunless sea.

So twice five miles of fertile ground

With walls and towers were girdled round:

And there were gardens bright with sinuous rills,

Where blossomed many an incense-bearing tree;

And here were forests ancient as the hills,

Enfolding sunny spots of greenery.

But oh! that deep romantic chasm which slanted

Down the green hill athwart a cedarn cover!

A savage place! as holy and enchanted

As e’er beneath a waning moon was haunted

By woman wailing for her demon-lover!

And from this chasm, with ceaseless turmoil seething,

As if this earth in fast thick pants were breathing,

A mighty fountain momently was forced:

Amid whose swift half-intermitted burst

Huge fragments vaulted like rebounding hail,

Or chaffy grain beneath the thresher’s flail:

And ‘mid these dancing rocks at once and ever

It flung up momently the sacred river.

Five miles meandering with a mazy motion

Through wood and dale the sacred river ran,

Then reached the caverns measureless to man,

And sank in tumult to a lifeless ocean:

And ‘mid this tumult Kubla heard from far

Ancestral voices prophesying war!

The shadow of the dome of pleasure

Floated midway on the waves;

Where was heard the mingled measure

From the fountain and the caves.

It was a miracle of rare device,

A sunny pleasure-dome with caves of ice!

A damsel with a dulcimer

In a vision once I saw:

It was an Abyssinian maid,

And on her dulcimer she played,

Singing of Mount Abora.

Could I revive within me

Her symphony and song,

To such a deep delight ‘twould win me

That with music loud and long

I would build that dome in air,

That sunny dome! those caves of ice!

And all who heard should see them there,

And all should cry, Beware! Beware!

His flashing eyes, his floating hair!

Weave a circle round him thrice,

And close your eyes with holy dread,

For he on honey-dew hath fed

And drunk the milk of Paradise.

Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772 – 1834)

Xanadu – Kubla Khan

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive C-D, Coleridge, Coleridge, Samuel Taylor

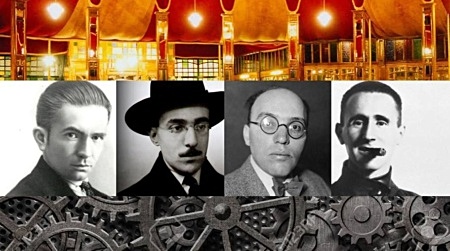

Magisch-industrieel variété met muziek, zang, magie en poëzie tijdens ‘O grote moderne geluiden’ bij het Pianolamuseum op zaterdagavond 15 april 2017

O grote moderne geluiden

Stichting Feest der Poëzie presenteert “O grote moderne geluiden” – magisch-industrieel variété met dada, futurisme, Berlijnse cabaretliederen, magie en poëzie. Verwonderaar Arjan van Vembde, klassiek liedduo Susanne Winkler en Daan van de Velde en voordrachtskunstenaar Simon Mulder brengen u in de frivole maar gevaarlijke sfeer van het begin van de vorige eeuw. Voor de pauze een Berlijns cabaret met magie en werk van o.a. Paul van Ostaijen, Bertolt Brecht en Kurt Weill, na de pauze een futuristische totaalvoordracht van Fernando Pessoa’s ‘Triomfode’ met muziek en zang. Vorig jaar een succes op Estival da Estrela in Portugal, dit jaar bij het Pianola Museum.

Brecht, Weill, Van Ostayen en Pessoa

Het programma bestaat uit liederen voor piano en sopraan van Kurt Weill op teksten van Bertolt Brecht, dadaïstische gedichten van Paul van Ostayen en als grote klapper de tot voordrachttheaterstuk met muziek en zang bewerkte Triomfode van Pessoa’s heteroniem Álvaro de Campos: een futuristische liefdesverklaring aan de zware industrie en de moderne consumptiemaatschappij.

Ewoud Kieft over oorlogsenthousiasme

Historicus Ewoud Kieft is schrijver van ‘Oorlogsenthousiasme’ over de aanloop naar de Eerste Wereldoorlog. Het boek is uitgekomen bij De Bezige Bij en werd genomineerd voor de Libris Geschiedenis Prijs. Hij komt het programma inleiden met een bespreking van de achtergrond van de gebrachte teksten in het kader van de aanloop naar en gevolgen van de Eerste Wereldoorlog.

Locatie: Pianola Museum, Westerstraat 106, Amsterdam

Datum: zaterdag 15 april

Zaal open: 20:00 uur

Aanvang: 20:30 uur

Entree: 15,- euro p.p. of 12,50 euro p.p. met korting (Stadspas, CJP, student, 65+)

Meer informatie: www.feestderpoezie.nl.

reservering via info@pianola.nl

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Art & Literature News, Bertolt Brecht, DANCE & PERFORMANCE, Feest der Poëzie, Literary Events, MUSIC, Ostaijen, Paul van, Pessoa, Fernando, POETRY ARCHIVE, THEATRE

Novalis

Armenmitleid

Sag an, mein Mund, warum gab dir zum Sange

Gott Dichtergeist und süßen Wohlklang zu,

Ja wahrlich auch, daß du im hohen Drange

Den Reichen riefst aus träger, stumpfer Ruh.

Denn kann nicht Sang vom Herzen himmlisch rühren,

Hat er nicht oft vom Lasterschlaf erweckt;

Kann er die Herzen nicht am Leitband führen,

Wenn er sie aus der Dumpfheit aufgeschreckt.

Wohlauf; hört mich ihr schwelgerischen Reichen,

Hört mich doch mehr noch euren innren Ruf,

Schaut um euch her, seht Arme hülflos schleichen,

Und fühlt, daß euch ein Vater nur erschuf.

Novalis (1772 – 1801)

Gedicht: Armenmitleid

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive M-N, Novalis, Novalis

The Surgeon Talks

The Surgeon Talks

by Arthur Conan Doyle

“Men die of the diseases which they have studied most,” remarked the surgeon, snipping off the end of a cigar with all his professional neatness and finish. “It’s as if the morbid condition was an evil creature which, when it found itself closely hunted, flew at the throat of its pursuer. If you worry the microbes too much they may worry you. I’ve seen cases of it, and not necessarily in microbic diseases either. There was, of course, the well-known instance of Liston and the aneurism; and a dozen others that I could mention. You couldn’t have a clearer case than that of poor old Walker of St. Christopher’s. Not heard of it? Well, of course, it was a little before your time, but I wonder that it should have been forgotten. You youngsters are so busy in keeping up to the day that you lose a good deal that is interesting of yesterday.

“Walker was one of the best men in Europe on nervous disease. You must have read his little book on sclerosis of the posterior columns. It’s as interesting as a novel, and epoch-making in its way. He worked like a horse, did Walker—huge consulting practice—hours a day in the clinical wards—constant original investigations. And then he enjoyed himself also. ‘De mortuis,’ of course, but still it’s an open secret among all who knew him. If he died at forty-five, he crammed eighty years into it. The marvel was that he could have held on so long at the pace at which he was going. But he took it beautifully when it came.

“I was his clinical assistant at the time. Walker was lecturing on locomotor ataxia to a wardful of youngsters. He was explaining that one of the early signs of the complaint was that the patient could not put his heels together with his eyes shut without staggering. As he spoke, he suited the action to the word. I don’t suppose the boys noticed anything. I did, and so did he, though he finished his lecture without a sign.

“When it was over he came into my room and lit a cigarette.

“‘Just run over my reflexes, Smith,’ said he.

“There was hardly a trace of them left. I tapped away at his knee-tendon and might as well have tried to get a jerk out of that sofa-cushion. He stood with his eyes shut again, and he swayed like a bush in the wind.

“‘So,’ said he, ‘it was not intercostal neuralgia after all.’

“Then I knew that he had had the lightning pains, and that the case was complete. There was nothing to say, so I sat looking at him while he puffed and puffed at his cigarette. Here he was, a man in the prime of life, one of the handsomest men in London, with money, fame, social success, everything at his feet, and now, without a moment’s warning, he was told that inevitable death lay before him, a death accompanied by more refined and lingering tortures than if he were bound upon a Red Indian stake. He sat in the middle of the blue cigarette cloud with his eyes cast down, and the slightest little tightening of his lips. Then he rose with a motion of his arms, as one who throws off old thoughts and enters upon a new course.

“‘Better put this thing straight at once,’ said he. ‘I must make some fresh arrangements. May I use your paper and envelopes?’

“He settled himself at my desk and he wrote half a dozen letters. It is not a breach of confidence to say that they were not addressed to his professional brothers. Walker was a single man, which means that he was not restricted to a single woman. When he had finished, he walked out of that little room of mine, leaving every hope and ambition of his life behind him. And he might have had another year of ignorance and peace if it had not been for the chance illustration in his lecture.

“It took five years to kill him, and he stood it well. If he had ever been a little irregular he atoned for it in that long martyrdom. He kept an admirable record of his own symptoms, and worked out the eye changes more fully than has ever been done. When the ptosis got very bad he would hold his eyelid up with one hand while he wrote. Then, when he could not co-ordinate his muscles to write, he dictated to his nurse. So died, in the odour of science, James Walker, aet. 45.

“Poor old Walker was very fond of experimental surgery, and he broke ground in several directions. Between ourselves, there may have been some more ground-breaking afterwards, but he did his best for his cases. You know M’Namara, don’t you? He always wears his hair long. He lets it be understood that it comes from his artistic strain, but it is really to conceal the loss of one of his ears. Walker cut the other one off, but you must not tell Mac I said so.

“It was like this. Walker had a fad about the portio dura—the motor to the face, you know—and he thought paralysis of it came from a disturbance of the blood supply. Something else which counterbalanced that disturbance might, he thought, set it right again. We had a very obstinate case of Bell’s paralysis in the wards, and had tried it with every conceivable thing, blistering, tonics, nerve-stretching, galvanism, needles, but all without result. Walker got it into his head that removal of the ear would increase the blood supply to the part, and he very soon gained the consent of the patient to the operation.

“Well, we did it at night. Walker, of course, felt that it was something of an experiment, and did not wish too much talk about it unless it proved successful. There were half-a-dozen of us there, M’Namara and I among the rest. The room was a small one, and in the centre was in the narrow table, with a macintosh over the pillow, and a blanket which extended almost to the floor on either side. Two candles, on a side-table near the pillow, supplied all the light. In came the patient, with one side of his face as smooth as a baby’s, and the other all in a quiver with fright. He lay down, and the chloroform towel was placed over his face, while Walker threaded his needles in the candle light. The chloroformist stood at the head of the table, and M’Namara was stationed at the side to control the patient. The rest of us stood by to assist.

“Well, the man was about half over when he fell into one of those convulsive flurries which come with the semi-unconscious stage. He kicked and plunged and struck out with both hands. Over with a crash went the little table which held the candles, and in an instant we were left in total darkness. You can think what a rush and a scurry there was, one to pick up the table, one to find the matches, and some to restrain the patient who was still dashing himself about. He was held down by two dressers, the chloroform was pushed, and by the time the candles were relit, his incoherent, half-smothered shoutings had changed to a stertorous snore. His head was turned on the pillow and the towel was still kept over his face while the operation was carried through. Then the towel was withdrawn, and you can conceive our amazement when we looked upon the face of M’Namara.

“How did it happen? Why, simply enough. As the candles went over, the chloroformist had stopped for an instant and had tried to catch them. The patient, just as the light went out, had rolled off and under the table. Poor M’Namara, clinging frantically to him, had been dragged across it, and the chloroformist, feeling him there, had naturally claped the towel across his mouth and nose. The others had secured him, and the more he roared and kicked the more they drenched him with chloroform. Walker was very nice about it, and made the most handsome apologies. He offered to do a plastic on the spot, and make as good an ear as he could, but M’Namara had had enough of it. As to the patient, we found him sleeping placidly under the table, with the ends of the blanket screening him on both sides. Walker sent M’Namara round his ear next day in a jar of methylated spirit, but Mac’s wife was very angry about it, and it led to a good deal of ill-feeling.

“Some people say that the more one has to do with human nature, and the closer one is brought in contact with it, the less one thinks of it. I don’t believe that those who know most would uphold that view. My own experience is dead against it. I was brought up in the miserable-mortal-clay school of theology, and yet here I am, after thirty years of intimate acquaintance with humanity, filled with respect for it. The evil lies commonly upon the surface. The deeper strata are good. A hundred times I have seen folk condemned to death as suddenly as poor Walker was. Sometimes it was to blindness or to mutilations which are worse than death. Men and women, they almost all took it beautifully, and some with such lovely unselfishness, and with such complete absorption in the thought of how their fate would affect others, that the man about town, or the frivolously-dressed woman has seemed to change into an angel before my eyes. I have seen death-beds, too, of all ages and of all creeds and want of creeds. I never saw any of them shrink, save only one poor, imaginative young fellow, who had spent his blameless life in the strictest of sects. Of course, an exhausted frame is incapable of fear, as anyone can vouch who is told, in the midst of his sea-sickness, that the ship is going to the bottom. That is why I rate courage in the face of mutilation to be higher than courage when a wasting illness is fining away into death.

“Now, I’ll take a case which I had in my own practice last Wednesday. A lady came in to consult me—the wife of a well-known sporting baronet. The husband had come with her, but remained, at her request, in the waiting-room. I need not go into details, but it proved to be a peculiarly malignant case of cancer. ‘I knew it,’ said she. ‘How long have I to live?’ ‘I fear that it may exhaust your strength in a few months,’ I answered. ‘Poor old Jack!’ said she. ‘I’ll tell him that it is not dangerous.’ ‘Why should you deceive him?’ I asked. ‘Well, he’s very uneasy about it, and he is quaking now in the waiting-room. He has two old friends to dinner to-night, and I haven’t the heart to spoil his evening. To-morrow will be time enough for him to learn the truth.’ Out she walked, the brave little woman, and a moment later her husband, with his big, red face shining with joy came plunging into my room to shake me by the hand. No, I respected her wish and I did not undeceive him. I dare bet that evening was one of the brightest, and the next morning the darkest, of his life.

“It’s wonderful how bravely and cheerily a woman can face a crushing blow. It is different with men. A man can stand it without complaining, but it knocks him dazed and silly all the same. But the woman does not lose her wits any more than she does her courage. Now, I had a case only a few weeks ago which would show you what I mean. A gentleman consulted me about his wife, a very beautiful woman. She had a small tubercular nodule upon her upper arm, according to him. He was sure that it was of no importance, but he wanted to know whether Devonshire or the Riviera would be the better for her. I examined her and found a frightful sarcoma of the bone, hardly showing upon the surface, but involving the shoulder-blade and clavicle as well as the humerus. A more malignant case I have never seen. I sent her out of the room and I told him the truth. What did he do? Why, he walked slowly round that room with his hands behind his back, looking with the greatest interest at the pictures. I can see him now, putting up his gold pince-nez and staring at them with perfectly vacant eyes, which told me that he saw neither them nor the wall behind them. ‘Amputation of the arm?’ he asked at last. ‘And of the collar-bone and shoulder-blade,’ said I. ‘Quite so. The collar-bone and shoulder-blade,’ he repeated, still staring about him with those lifeless eyes. It settled him. I don’t believe he’ll ever be the same man again. But the woman took it as bravely and brightly as could be, and she has done very well since. The mischief was so great that the arm snapped as we drew it from the night-dress. No, I don’t think that there will be any return, and I have every hope of her recovery.

“The first patient is a thing which one remembers all one’s life. Mine was commonplace, and the details are of no interest. I had a curious visitor, however, during the first few months after my plate went up. It was an elderly woman, richly dressed, with a wickerwork picnic basket in her hand. This she opened with the tears streaming down her face, and out there waddled the fattest, ugliest, and mangiest little pug dog that I have ever seen. ‘I wish you to put him painlessly out of the world, doctor,’ she cried. ‘Quick, quick, or my resolution may give way.’ She flung herself down, with hysterical sobs, upon the sofa. The less experienced a doctor is, the higher are his notions of professional dignity, as I need not remind you, my young friend, so I was about to refuse the commission with indignation, when I bethought me that, quite apart from medicine, we were gentleman and lady, and that she had asked me to do something for her which was evidently of the greatest possible importance in her eyes. I led off the poor little doggie, therefore, and with the help of a saucerful of milk and a few drops of prussic acid his exit was as speedy and painless as could be desired. ‘Is it over?’ she cried as I entered. It was really tragic to see how all the love which should have gone to husband and children had, in default of them, been centred upon this uncouth little animal. She left, quite broken down, in her carriage, and it was only after her departure that I saw an envelope sealed with a large red seal, and lying upon the blotting pad of my desk. Outside, in pencil, was written: ‘I have no doubt that you would willingly have done this without a fee, but I insist upon your acceptance of the enclosed.’ I opened it with some vague notions of an eccentric millionaire and a fifty-pound note, but all I found was a postal order for four and sixpence. The whole incident struck me as so whimsical that I laughed until I was tired. You’ll find there’s so much tragedy in a doctor’s life, my boy, that he would not be able to stand it if it were not for the strain of comedy which comes every now and then to leaven it.

“The first patient is a thing which one remembers all one’s life. Mine was commonplace, and the details are of no interest. I had a curious visitor, however, during the first few months after my plate went up. It was an elderly woman, richly dressed, with a wickerwork picnic basket in her hand. This she opened with the tears streaming down her face, and out there waddled the fattest, ugliest, and mangiest little pug dog that I have ever seen. ‘I wish you to put him painlessly out of the world, doctor,’ she cried. ‘Quick, quick, or my resolution may give way.’ She flung herself down, with hysterical sobs, upon the sofa. The less experienced a doctor is, the higher are his notions of professional dignity, as I need not remind you, my young friend, so I was about to refuse the commission with indignation, when I bethought me that, quite apart from medicine, we were gentleman and lady, and that she had asked me to do something for her which was evidently of the greatest possible importance in her eyes. I led off the poor little doggie, therefore, and with the help of a saucerful of milk and a few drops of prussic acid his exit was as speedy and painless as could be desired. ‘Is it over?’ she cried as I entered. It was really tragic to see how all the love which should have gone to husband and children had, in default of them, been centred upon this uncouth little animal. She left, quite broken down, in her carriage, and it was only after her departure that I saw an envelope sealed with a large red seal, and lying upon the blotting pad of my desk. Outside, in pencil, was written: ‘I have no doubt that you would willingly have done this without a fee, but I insist upon your acceptance of the enclosed.’ I opened it with some vague notions of an eccentric millionaire and a fifty-pound note, but all I found was a postal order for four and sixpence. The whole incident struck me as so whimsical that I laughed until I was tired. You’ll find there’s so much tragedy in a doctor’s life, my boy, that he would not be able to stand it if it were not for the strain of comedy which comes every now and then to leaven it.

“And a doctor has very much to be thankful for also. Don’t you ever forget it. It is such a pleasure to do a little good that a man should pay for the privilege instead of being paid for it. Still, of course, he has his home to keep up and his wife and children to support. But his patients are his friends—or they should be so. He goes from house to house, and his step and his voice are loved and welcomed in each. What could a man ask for more than that? And besides, he is forced to be a good man. It is impossible for him to be anything else. How can a man spend his whole life in seeing suffering bravely borne and yet remain a hard or a vicious man? It is a noble, generous, kindly profession, and you youngsters have got to see that it remains so.”

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (1859 – 1930)

Round the Red Lamp: Being Facts and Fancies of Medical Life

The Surgeon Talks (#15) – Last Chapter

Round the Red Lamp: Being Facts and Fancies of Medical Life

by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

– Table of Contents

– The Preface

Behind the Times. (#01)

His First Operation. (#02)

A Straggler of ‘15. (#03)

The Third Generation. (#04)

A False Start. (#05)

The Curse of Eve. (#06)

Sweethearts. (#07)

A Physiologist’s Wife. (#08)

The Case of Lady Sannox. (#09)

A Question of Diplomacy. (#10)

A Medical Document. (#11)

Lot No. 249. (#12)

The Los Amigos Fiasco. (#13)

The Doctors of Hoyland. (#14)

The Surgeon Talks. (#15)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Doyle, Arthur Conan, Doyle, Arthur Conan, DRUGS & DISEASE & MEDICINE & LITERATURE, Round the Red Lamp

Emile Verhaeren

Mourir

Un soir plein de pourpres et de fleuves vermeils

Pourrit, par au-delà des plaines diminuées,

Et fortement, avec les poings de ses nuées,

Sur l’horizon verdâtre, écrase des soleils.

Saison massive! Et comme Octobre, avec paresse

Et nonchaloir, se gonfle et meurt dans ce décor

Pommes ! caillots de feu ; raisins ! chapelets d’or,

Que le doigté tremblant des lumières caresse,

Une dernière fois, avant l’hiver. Le vol

Des grands corbeaux ? il vient. Mais aujourd’hui, c’est l’heure

Encor des feuillaisons de laque – et la meilleure.

Les pousses des fraisiers ensanglantent le sol,

Le bois tend vers le ciel ses mains de feuilles rousses

Et du bronze et du fer sonnent, là-bas, au loin.

Une odeur d’eau se mêle à des senteurs de coing

Et des parfums d’iris à des parfums de mousses.

Et l’étang plane et clair reflète énormément

Entre de fins bouleaux, dont le branchage bouge,

La lune, qui se lève épaisse, immense et rouge,

Et semble un beau fruit mûr, éclos placidement.

Mourir ainsi, mon corps, mourir, serait le rêve!

Sous un suprême afflux de couleurs et de chants,

Avec, dans les regards, des ors et des couchants,

Avec, dans le cerveau, des rivières de sève.

Mourir! comme des fleurs trop énormes, mourir!

Trop massives et trop géantes pour la vie!

La grande mort serait superbement servie

Et notre immense orgueil n’aurait rien à souffrir!

Mourir, mon corps, ainsi que l’automne, mourir!

Emile Verhaeren (1855-1916) poésie

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive U-V, Verhaeren, Emile

Oscar Wilde

Amor Intellectualis

Oft have we trod the vales of Castaly

And heard sweet notes of sylvan music blown

From antique reeds to common folk unknown:

And often launched our bark upon that sea

Which the nine Muses hold in empery,

And ploughed free furrows through the wave and foam,

Nor spread reluctant sail for more safe home

Till we had freighted well our argosy.

Of which despoilèd treasures these remain,

Sordello’s passion, and the honied line

Of young Endymion, lordly Tamburlaine

Driving his pampered jades, and more than these,

The seven-fold vision of the Florentine,

And grave-browed Milton’s solemn harmonies.

Oscar Wilde (1854 – 1900)

Amor Intellectualis

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive W-X, Wilde, Oscar, Wilde, Oscar

Robert Bridges

The Evening Darkens Over

The evening darkens over

After a day so bright,

The windcapt waves discover

That wild will be the night.

There’s sound of distant thunder.

The latest sea-birds hover

Along the cliff’s sheer height;

As in the memory wander

Last flutterings of delight,

White wings lost on the white.

There’s not a ship in sight;

And as the sun goes under,

Thick clouds conspire to cover

The moon that should rise yonder.

Thou art alone, fond lover

Robert Seymour Bridges (1844 – 1930)

The Evening Darkens Over

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Bridges, Robert

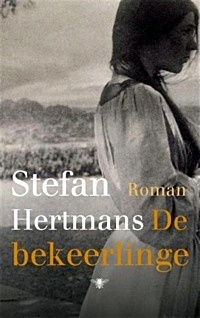

De E. du Perronprijs 2016 is toegekend aan Stefan Hertmans voor zijn roman De bekeerlinge (Uitgeverij De Bezige Bij) vanwege de kracht om tegenstrijdigheden met elkaar te verbinden en de kunst om in alles het gelijke op te zoeken. De andere genomineerden waren Rodaan Al Galidi met Hoe ik talent voor het leven kreeg (Uitgeverij Jurgen Maas) en Carolijn Visser met Selma. Aan Hitler ontsnapt, gevangene van Mao (Uitgeverij Augustus).

De E. du Perronprijs 2016 is toegekend aan Stefan Hertmans voor zijn roman De bekeerlinge (Uitgeverij De Bezige Bij) vanwege de kracht om tegenstrijdigheden met elkaar te verbinden en de kunst om in alles het gelijke op te zoeken. De andere genomineerden waren Rodaan Al Galidi met Hoe ik talent voor het leven kreeg (Uitgeverij Jurgen Maas) en Carolijn Visser met Selma. Aan Hitler ontsnapt, gevangene van Mao (Uitgeverij Augustus).

De prijs bestaat uit een geldbedrag van €2500 euro en een textiel object, ontworpen door studio ‘by aaaa’ (Moyra Besjes en Natasja Lauwers) en vervaardigd bij het TextielMuseum in Tilburg.

De uitreiking vindt plaats op donderdag 13 april, aanvang 20.00 uur bij brabants kenniscentrum voor kunst en cultuur (bkkc), Spoorlaan 21 te Tilburg.

Voorafgaand aan de uitreiking houdt schrijver Arnon Grunberg de E. du Perronlezing met als titel ‘Het paradijs’.

De E. du Perronprijs is een initiatief van de gemeente Tilburg, de School of Humanities van Tilburg University en brabants kenniscentrum voor kunst en cultuur (bkkc). In 2015 won Ilja Leonard Pfeijffer de prijs voor zijn dichtbundel Idyllen (2015), zijn pamflet Asielzoekers en zijn columns in NRC Next. Andere laureaten waren onder meer Warna Oosterbaan en Theo Baart (2015), Mohammed Benzakour (2013), Koen Peeters (2012), Ramsey Nasr (2011), Alice Boot & Rob Woortman (2010), Abdelkader Benali (2009), Adriaan van Dis (2008) en Guus Kuijer (2007).

# meer info op website tilburg university

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Abdelkader Benali, Art & Literature News, Eddy du Perron, Hertmans, Stefan, Literary Events

William Shakespeare

(1564-1616)

But, soft! what light through yonder window breaks?

“But, soft! what light through yonder window breaks?

It is the east, and Juliet is the sun.

Arise, fair sun, and kill the envious moon,

Who is already sick and pale with grief,

That thou her maid art far more fair than she:

Be not her maid, since she is envious;

Her vestal livery is but sick and green

And none but fools do wear it; cast it off.

It is my lady, O, it is my love!

O, that she knew she were!

She speaks yet she says nothing: what of that?

Her eye discourses; I will answer it.

I am too bold, ’tis not to me she speaks:

Two of the fairest stars in all the heaven,

Having some business, do entreat her eyes

To twinkle in their spheres till they return.

What if her eyes were there, they in her head?

The brightness of her cheek would shame those stars,

As daylight doth a lamp; her eyes in heaven

Would through the airy region stream so bright

That birds would sing and think it were not night.

See, how she leans her cheek upon her hand!

O, that I were a glove upon that hand,

That I might touch that cheek!”

William Shakespeare, Romeo and Juliet

Shakespeare 401 (1616 – 2017)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Shakespeare, William

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature