Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

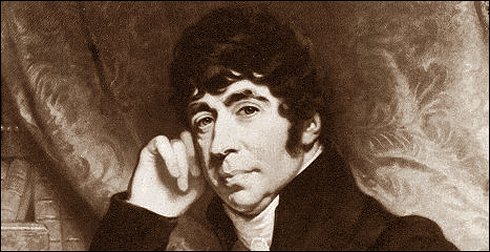

W i l l e m B i l d e r d i j k

(1756-1831)

P o ë z y

Cui mens divinor (H O R A T I U S)

Zing met daavrende oorlogstoonen

Waar de woeste moord in brult,

’t Blinkend loof van zegekroonen

Dat des strijders hoofd omhult:

Brom den donder der musketten —

Kletter ’t ramm’len van het staal —

Bruis het brieschen der genetten —

Na, in Dichterlijken praal.

Kweel het tripplend maagdereien,

’t Ruischen van den zilvren vliet,

Door den toon der veldschalmeien

En het piepend Herdersriet:

Meng aan ’t tjilpnes boschgeschater

Filomeles orgelkeel;

Aan het stortend stroomgeklater,

’t Zuizen van het myrthprieel:

Huppele op uw Cythersnaren

Liefdelust of oorlogsmoed,

Naar het steigren van uw bloed!

Welig zal uw zangtoon vloeien,

Als hy aan de ziel ontstijgt;

Maar, ontbreekt dat innig gloeien,

Arme toonverwoesters, zwijgt!

Ja, die zang zal boezems treffen,

Hart en zin in kluisters slaan,

Zielen, boven de aard verheffen;

Maar, ô wierook aan geen waan; —

Tooi geen eigen hartsgevoelen,

Met een valsch-ontleende pracht: —

Wacht u, op den lof te doelen

Van een nietig wangeslacht!

Ach! die lof van laag gebroedsel,

Aarde en eigenzucht verkleefd,

Is vergif voor zielenvoedsel,

Dampt de lucht waarin gy zweeft.

Neem uw vlucht in hooger kringen,

Van hun ademwalming vrij,

Dan-alleen is ’t waarlijk ZINGEN,

Dan-alleen is ’t POËZY!

Ja, uit eigen hart geschoten,

Is de zangtoon ware zang;

Vrij als Edens lustgenooten,

Kent hy kunst- noch regeldwang.

Neen, de vloeistof waar we in drijven,

Is te hoog voor aardsche vlucht,

En, den echten toon te stijven

Eischt een zuiver Hemellucht.

Waar wy held- of zegepalmen,

Zomerlust of lentebloem,

Waar wy vreugd of liefde galmen,

Zingen we EEN-alleen ten roem!

U, ô bron van ZIJN en LEVEN,

Aan wiens oogwenk alles hangt!

U-alleen zij de eer gegeven,

Welk een stof ons lied omvangt!

Wat wy in het schepsel eeren

Is een dankcijns, U gewijd:

U behoort hy, Heer der Heeren,

U die door U-zelven zijt!

Dan, wat slaan wy slappe wieken

Naar dien zuivren luchtstroom uit,

Eer het zalig morgenkrieken

Zich aan ’t starend oog ontsluit!

Ach, wat zegt dat vleuglenkleppen

Als de gave slagpen faalt,

Om zich steiler vaart te scheppen,

Waar de dag ons tegenstraalt!

Doch Gy, GOËL, schenkt ons krachten,

Gy, der Hemelharpen lof,

Wien van Serafs, Thronen, Machten,

De eergalm weêrklinkt uit ons stof!

Zwak, onzuiver, en ontëngeld

In de sterfelijke borst,

En met wangeluid doormengeld,

U onwaardig, Hemelvorst:

Ja, Verlosser, U onwaardig;

Maar, wanneer Uw Geest ons roert,

Uit een hart, door U wilvaardig,

Tot Uw zetel opgevoerd.

Schenk, ô schenk hun die U loven,

Dropplen uit uw Hemelwel;

Dat zy ’t Aardsch geknars verdoven,

En het vloekgejoel der Hel!

1825.

.jpg)

Willem Bilderdijk gedichten

k e m p i s p o e t r y m a g a z i n e

More in: Bilderdijk, Willem

J a n e A u s t e n

(1775 – 1817)

When Stretch’d on One’s Bed

When stretch’d on one’s bed

With a fierce-throbbing head,

Which preculdes alike thought or repose,

How little one cares

For the grandest affairs

That may busy the world as it goes!

How little one feels

For the waltzes and reels

Of our Dance-loving friends at a Ball!

How slight one’s concern

To conjecture or learn

What their flounces or hearts may befall.

How little one minds

If a company dines

On the best that the Season affords!

How short is one’s muse

O’er the Sauces and Stews,

Or the Guests, be they Beggars or Lords.

How little the Bells,

Ring they Peels, toll they Knells,

Can attract our attention or Ears!

The Bride may be married,

The Corse may be carried

And touch nor our hopes nor our fears.

Our own bodily pains

Ev’ry faculty chains;

We can feel on no subject besides.

Tis in health and in ease

We the power must seize

For our friends and our souls to provide.

.jpg)

k e m p i s p o e t r y m a g a z i n e

More in: Austen, Jane, Austen, Jane

Albrecht Rodenbach

(1856 – 1880)

Vaarwel

De wereld in, gij Liedjes en Gedichten

der eerste jeugd, en, vraagt men wie gij zijt

en wat gij, vreemdelingen, doen komt, antwoordt,

en zegt met vroeden zin, want u ook past

het peilend denken, kinders van gevoel

en scheppende begeestring: "Wij zijn stralen

uit Leven en Natuur geschongen, vonken

die onze dichter uit de keien sloeg

langs zijne bane; klanken afgeluisterd

uit die onduidelike harmonie

van hemel, veld en zee en zielenwereld.–

Wat ware zonder ‘t Licht het bont Heelal?

Wat zijn der velden vrolike geruchten

den wandelaar, indien hen zijne ziel

niet vatten en tot harmonieën kan smelten?

Wat is het Leven zonder Oorbeeld en

Poësis? O! eene onvolledigheid,

eene ijdelheid waarin de zielen kwijnen

verdord. En toch roept de ingeboren weêrklank

des Vloeks die eens het wroetelend Menschdom sloeg

en schreeuwt het zingend Oorbeeld tegen, en

vol onbewuste wanhoop pijnt hij om

het buiten ziel en leven te verbannen,

zijn eigen tot een straf; gelijk die boeters

in ‘t heimelik en somber Heidendom

die, dansend voor een goddelik wangedrocht,

in bloeddolheid hun eigen lijf verminken.

Wij komen, stemmen van het Oorbeeld, wij,

voor wie ons hooren wilt ons liedje zingen."

Zoo zult gij spreken, en vaarwel daarmede,

o Dichten jong en licht: ons roept de tijd

tot hooger peil en zwaarder bezigheid.

Albrecht Rodenbach gedicht

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Archive Q-R

.jpg)

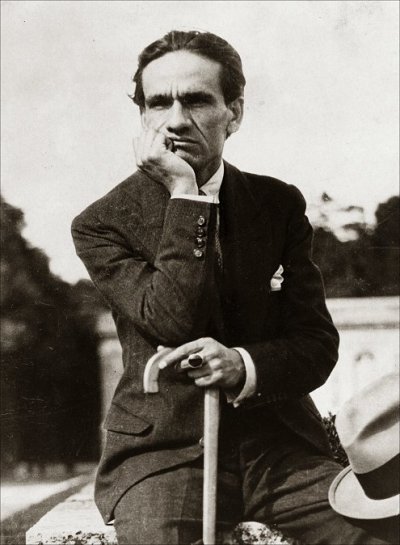

E u g e n e M a r a i s

(1871-1936)

D i e O o r w i n n a a r s

By die kindergrafte uit die Konsentrasiekamp van Nylstroom

Oorwinnaars vir ons volk,

bly u vir al wat beste in ons is ‘n ewig’ tolk;

nooit weer sal vyandsvoet u stof so diep vertrap en smoor

dat ons u langer nie kan sien – en hoor.

Nie onse Helde, wat die magtig’ leër

op glansryk’ velde kon weerstaan en keer;

nie onse Seuns, wat aan die galg en teen die muur

die diepe liefde vir hul eie moes verduur;

nie onse Moeders, wat met bloeiend hart en seer,

in swart Getsemane die ware smart moes leer;

nie onse Generaals, vereer met krans en riddersnoer;

– was waardig vir ons volk die hoë stryd te voer

en te oorwin.

Nie ons, met vuile hand en hart ontrou was waardig

om die vaandel hoog te hou.

Maar u, o bleke spokies, in U kermend’, klagend’ wee,

staan voor ons ewiglik beskermend – uit die lang verlee.

E u g e n e M a r a i s p o e t r y

fleursdumal.nl m a g a z i n e

More in: Archive M-N, Eugène Marais, Marais, Eugène

![]()

Jose Marti

(1853-1895)

Pour Out Your Sorrows

My Heart (Verse XLVI)

Pour out your sorrows, my heart,

But let none discover where;

For my pride makes me forbear

My heart’s sorrows to impart.

I love you, Verse, my friend true,

Because when in pieces torn

My heart’s too burdened, you’ve borne

All my sorrows upon you.

For me you suffer and bear

Upon your amorous lap

Every anguish, every slap

That my painful love leaves there.

That I may love, in peace with all,

And do good works, as my goal,

You thrash your waves, rise and fall,

With whatever weighs my soul.

That I may cross with fierce stride,

Pure and without hate, this vale,

You drag yourself, hard and pale,

The loving friend at my side.

And so my life its way will wend

To the sky serene and pure,

While you my sorrows endure

And with divine patience tend.

Because I know this cruel habit

Of throwing myself on you

Upsets your harmony true

And tries your gentle spirit;

Because on your breast I’ve shed

All of my sorrows and torments,

And have whipped your quiet currents,

Which are here white and there red,

And then pale as death become,

At once roaring and attacking,

And then beneath the weight cracking

Of pain it can’t overcome: —

Should I the advice have taken

Of a heart so misbegotten,

Would have me leave you forgotten

Who never me has forsaken?

Verse, there’s a God, they aver

To whom the dying appealed;

Verse, as one our fates our sealed:

We are damned or saved together!

Vierte Corazón tu pena

(Verso XLVI)

Vierte, corazón, tu pena

Donde no se llegue a ver,

Por soberbia, y por no ser

Motivo de pena ajena.

Yo te quiero, verso amigo,

Porque cuando siento el pecho

Ya muy cargado y deshecho,

Parto la carga contigo.

Tú me sufres, tú aposentas

En tu regazo amoroso,

Todo mi amor doloroso,

Todas mis ansias y afrentas.

Tú, porque yo pueda en calma

Amar y hacer bien, consientes

En enturbiar tus corrientes

Con cuanto me agobia el alma.

Tú, porque yo cruce fiero

La tierra, y sin odio, y puro,

Te arrastras, pálido y duro,

Mi amoroso compañero.

Mi vida así se encamina

Al cielo limpia y serena,

Y tú me cargas mi pena

Con tu paciencia divina.

Y porque mi cruel costumbre

De echarme en ti te desvía

De su dichosa armonía

Y natural mansedumbre;

Porque mis penas arrojo

Sobre tu seno, y lo azotan,

Y tu corriente alborotan,

Y acá lívido, allá rojo,

Blanco allá como la muerte,

Ora arremetes y ruges,

Ora con el peso crujes

De un dolor más que tú fuerte,

¿Habré, como me aconseja

Un corazón mal nacido,

De dejar en el olvido

A aquel que nunca me deja?

¡Verso, nos hablan de un Dios

Adonde van los difuntos:

Verso, o nos condenan juntos,

O nos salvamos los dos!

Jose Marti poetry

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Archive M-N

.jpg)

E m i l y D i c k i n s o n

(1830-1886)

T h e M o u n t a i n

The mountain sat upon the plain

In his eternal chair,

His observation omnifold,

His inquest everywhere.

The seasons prayed around his knees,

Like children round a sire:

Grandfather of the days is he,

Of dawn the ancestor.

.jpg)

Emily Dickinson poetry

k e m p i s p o e t r y m a g a z i n e

More in: Dickinson, Emily

.jpg)

Virginia Woolf

(1882-1941)

“I Am Christina Rossetti”

On the fifth of this December [1930] Christina Rossetti will celebrate her centenary, or, more properly speaking, we shall celebrate it for her, and perhaps not a little to her distress, for she was one of the shyest of women, and to be spoken of, as we shall certainly speak of her, would have caused her acute discomfort. Nevertheless, it is inevitable; centenaries are inexorable; talk of her we must. We shall read her life; we shall read her letters; we shall study her portraits, speculate about her diseases — of which she had a great variety; and rattle the drawers of her writing-table, which are for the most part empty. Let us begin with the biography — for what could be more amusing? As everybody knows, the fascination of reading biographies is irresistible. No sooner have we opened the pages of Miss Sandars’s careful and competent book (Life of Christina Rossetti, by Mary F. Sandars. (Hutchinson)) than the old illusion comes over us. Here is the past and all its inhabitants miraculously sealed as in a magic tank; all we have to do is to look and to listen and to listen and to look and soon the little figures — for they are rather under life size — will begin to move and to speak, and as they move we shall arrange them in all sorts of patterns of which they were ignorant, for they thought when they were alive that they could go where they liked; and as they speak we shall read into their sayings all kinds of meanings which never struck them, for they believed when they were alive that they said straight off whatever came into their heads. But once you are in a biography all is different.

Here, then, is Hallam Street, Portland Place, about the year 1830; and here are the Rossettis, an Italian family consisting of father and mother and four small children. The street was unfashionable and the home rather poverty-stricken; but the poverty did not matter, for, being foreigners, the Rossettis did not care much about the customs and conventions of the usual middle-class British family. They kept themselves to themselves, dressed as they liked, entertained Italian exiles, among them organ-grinders and other distressed compatriots, and made ends meet by teaching and writing and other odd jobs. By degrees Christina detached herself from the family group. It is plain that she was a quiet and observant child, with her own way of life already fixed in her head — she was to write — but all the more did she admire the superior competence of her elders. Soon we begin to surround her with a few friends and to endow her with a few characteristics. She detested parties. She dressed anyhow. She liked her brother’s friends and little gatherings of young artists and poets who were to reform the world, rather to her amusement, for although so sedate, she was also whimsical and freakish, and liked making fun of people who took themselves with egotistic solemnity. And though she meant to be a poet she had very little of the vanity and stress of young poets; her verses seem to have formed themselves whole and entire in her head, and she did not worry very much what was said of them because in her own mind she knew that they were good. She had also immense powers of admiration — for her mother, for example, who was so quiet, and so sagacious, so simple and so sincere; and for her elder sister Maria, who had no taste for painting or for poetry, but was, for that very reason, perhaps more vigorous and effective in daily life. For example, Maria always refused to visit the Mummy Room at the British Museum because, she said, the Day of Resurrection might suddenly dawn and it would be very unseemly if the corpses had to put on immortality under the gaze of mere sight-seers — a reflection which had not struck Christina, but seemed to her admirable. Here, of course, we, who are outside the tank, enjoy a hearty laugh, but Christina, who is inside the tank and exposed to all its heats and currents, thought her sister’s conduct worthy of the highest respect. Indeed, if we look at her a little more closely we shall see that something dark and hard, like a kernel, had already formed in the centre of Christina Rossetti’s being.

It was religion, of course. Even when she was quite a girl her lifelong absorption in the relation of the soul with God had taken possession of her. Her sixty-four years might seem outwardly spent in Hallam Street and Endsleigh Gardens and Torrington Square, but in reality she dwelt in some curious region where the spirit strives towards an unseen God — in her case, a dark God, a harsh God — a God who decreed that all the pleasures of the world were hateful to Him. The theatre was hateful, the opera was hateful, nakedness was hateful — when her friend Miss Thompson painted naked figures in her pictures she had to tell Christina that they were fairies, but Christina saw through the imposture — everything in Christina’s life radiated from that knot of agony and intensity in the centre. Her belief regulated her life in the smallest particulars. It taught her that chess was wrong, but that whist and cribbage did not matter. But also it interfered in the most tremendous questions of her heart. There was a young painter called James Collinson, and she loved James Collinson and he loved her, but he was a Roman Catholic and so she refused him. Obligingly he became a member of the Church of England, and she accepted him. Vacillating, however, for he was a slippery man, he wobbled back to Rome, and Christina, though it broke her heart and for ever shadowed her life, cancelled the engagement. Years afterwards another, and it seems better founded, prospect of happiness presented itself. Charles Cayley proposed to her. But alas, this abstract and erudite man who shuffled about the world in a state of absent-minded dishabille, and translated the gospel into Iroquois, and asked smart ladies at a party “whether they were interested in the Gulf Stream”, and for a present gave Christina a sea mouse preserved in spirits, was, not unnaturally, a free thinker. Him, too, Christina put from her. Though “no woman ever loved a man more deeply”, she would not be the wife of a sceptic. She who loved the “obtuse and furry”— the wombats, toads, and mice of the earth — and called Charles Cayley “my blindest buzzard, my special mole”, admitted no moles, wombats, buzzards, or Cayleys to her heaven.

So one might go on looking and listening for ever. There is no limit to the strangeness, amusement, and oddity of the past sealed in a tank. But just as we are wondering which cranny of this extraordinary territory to explore next, the principal figure intervenes. It is as if a fish, whose unconscious gyrations we had been watching in and out of reeds, round and round rocks, suddenly dashed at the glass and broke it. A tea-party is the occasion. For some reason Christina went to a party given by Mrs. Virtue Tebbs. What happened there is unknown — perhaps something was said in a casual, frivolous, tea-party way about poetry. At any rate,

suddenly there uprose from a chair and paced forward into the centre of the room a little woman dressed in black, who announced solemnly, “I am Christina Rossetti!” and having so said, returned to her chair.

With those words the glass is broken. Yes [she seems to say], I am a poet. You who pretend to honour my centenary are no better than the idle people at Mrs. Tebb’s tea-party. Here you are rambling among unimportant trifles, rattling my writing-table drawers, making fun of the Mummies and Maria and my love affairs when all I care for you to know is here. Behold this green volume. It is a copy of my collected works. It costs four shillings and sixpence. Read that. And so she returns to her chair.

How absolute and unaccommodating these poets are! Poetry, they say, has nothing to do with life. Mummies and wombats, Hallam Street and omnibuses, James Collinson and Charles Cayley, sea mice and Mrs. Virtue Tebbs, Torrington Square and Endsleigh Gardens, even the vagaries of religious belief, are irrelevant, extraneous, superfluous, unreal. It is poetry that matters. The only question of any interest is whether that poetry is good or bad. But this question of poetry, one might point out if only to gain time, is one of the greatest difficulty. Very little of value has been said about poetry since the world began. The judgment of contemporaries is almost always wrong. For example, most of the poems which figure in Christina Rossetti’s complete works were rejected by editors. Her annual income from her poetry was for many years about ten pounds. On the other hand, the works of Jean Ingelow, as she noted sardonically, went into eight editions. There were, of course, among her contemporaries one or two poets and one or two critics whose judgment must be respectfully consulted. But what very different impressions they seem to gather from the same works — by what different standards they judge! For instance, when Swinburne read her poetry he exclaimed: “I have always thought that nothing more glorious in poetry has ever been written”, and went on to say of her New Year Hymn that it was

touched as with the fire and bathed as in the light of sunbeams, tuned as to chords and cadences of refluent sea-music beyond reach of harp and organ, large echoes of the serene and sonorous tides of heaven

Then Professor Saintsbury comes with his vast learning, and examines Goblin Market, and reports that

The metre of the principal poem [“Goblin Market”] may be best described as a dedoggerelised Skeltonic, with the gathered music of the various metrical progress since Spenser, utilised in the place of the wooden rattling of the followers of Chaucer. There may be discerned in it the same inclination towards line irregularity which has broken out, at different times, in the Pindaric of the late seventeenth and earlier eighteenth centuries, and in the rhymelessness of Sayers earlier and of Mr. Arnold later.

And then there is Sir Walter Raleigh:

I think she is the best poet alive. . . . The worst of it is you cannot lecture on really pure poetry any more than you can talk about the ingredients of pure water — it is adulterated, methylated, sanded poetry that makes the best lectures. The only thing that Christina makes me want to do, is cry, not lecture.

It would appear, then, that there are at least three schools of criticism: the refluent sea-music school; the line-irregularity school, and the school that bids one not criticise but cry. This is confusing; if we follow them all we shall only come to grief. Better perhaps read for oneself, expose the mind bare to the poem, and transcribe in all its haste and imperfection whatever may be the result of the impact. In this case it might run something as follows: O Christina Rossetti, I have humbly to confess that though I know many of your poems by heart, I have not read your works from cover to cover. I have not followed your course and traced your development. I doubt indeed that you developed very much. You were an instinctive poet. You saw the world from the same angle always. Years and the traffic of the mind with men and books did not affect you in the least. You carefully ignored any book that could shake your faith or any human being who could trouble your instincts. You were wise perhaps. Your instinct was so sure, so direct, so intense that it produced poems that sing like music in one’s ears — like a melody by Mozart or an air by Gluck. Yet for all its symmetry, yours was a complex song. When you struck your harp many strings sounded together. Like all instinctives you had a keen sense of the visual beauty of the world. Your poems are full of gold dust and “sweet geraniums’ varied brightness”; your eye noted incessantly how rushes are “velvet-headed”, and lizards have a “strange metallic mail”— your eye, indeed, observed with a sensual pre-Raphaelite intensity that must have surprised Christina the Anglo-Catholic. But to her you owed perhaps the fixity and sadness of your muse. The pressure of a tremendous faith circles and clamps together these little songs. Perhaps they owe to it their solidity. Certainly they owe to it their sadness — your God was a harsh God, your heavenly crown was set with thorns. No sooner have you feasted on beauty with your eyes than your mind tells you that beauty is vain and beauty passes. Death, oblivion, and rest lap round your songs with their dark wave. And then, incongruously, a sound of scurrying and laughter is heard. There is the patter of animals’ feet and the odd guttural notes of rooks and the snufflings of obtuse furry animals grunting and nosing. For you were not a pure saint by any means. You pulled legs; you tweaked noses. You were at war with all humbug and pretence. Modest as you were, still you were drastic, sure of your gift, convinced of your vision. A firm hand pruned your lines; a sharp ear tested their music. Nothing soft, otiose, irrelevant cumbered your pages. In a word, you were an artist. And thus was kept open, even when you wrote idly, tinkling bells for your own diversion, a pathway for the descent of that fiery visitant who came now and then and fused your lines into that indissoluble connection which no hand can put asunder:

But bring me poppies brimmed with sleepy death

And ivy choking what it garlandeth

And primroses that open to the moon.

Indeed so strange is the constitution of things, and so great the miracle of poetry, that some of the poems you wrote in your little back room will be found adhering in perfect symmetry when the Albert Memorial is dust and tinsel. Our remote posterity will be singing:

When I am dead, my dearest,

or:

My heart is like a singing bird,

when Torrington Square is a reef of coral perhaps and the fishes shoot in and out where your bedroom window used to be; or perhaps the forest will have reclaimed those pavements and the wombat and the ratel will be shuffling on soft, uncertain feet among the green undergrowth that will then tangle the area railings. In view of all this, and to return to your biography, had I been present when Mrs. Virtue Tebbs gave her party, and had a short elderly woman in black risen to her feet and advanced to the middle of the room, I should certainly have committed some indiscretion — have broken a paper-knife or smashed a tea-cup in the awkward ardour of my admiration when she said, “I am Christina Rossetti”.

.jpg)

Virginia Woolf: The Common Reader, Second Series

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Rossetti, Christina, Woolf, Virginia

Cesar Vallejo

(1892 – 1938)

Los heraldos negros

Hay golpes en la vida tan fuertes . . . ¡Yo no se!

Golpes como del odio de Dios; como si ante ellos;

la resaca de todo lo sufrido se empozara en el alma

¡Yo no se!

Son pocos; pero son . . . abren zanjas oscuras

en el rostro mas fiero y en el lomo mas fuerte,

Serán talvez los potros de bárbaros atilas;

o los heraldos negros que nos manda la Muerte

Son las caídas hondas de los Cristos del alma,

de alguna adorable que el Destino Blasfema,

Esos golpes sangrientos son las crepitaciones

de algún pan que en la puerta del horno se nos quema

Y el hombre….pobre…¡pobre!

Vuelve los ojos,

como cuando por sobre el hombro

nos llama una palmada;

vuelve los ojos locos,

y todo lo vivido

se empoza, como charco de culpa,

en la mirada.

Hay golpes en la vida, tan fuertes . . . ¡Yo no se!

Cesar Vallejo poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive U-V, Vallejo, Cesar

.jpg)

Over de grens

Cees van Raak (tekst)

Martje Ingenhoven (foto’s)

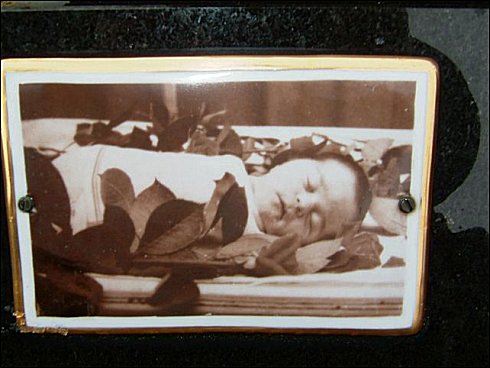

D o o d k i n d j e

Men heeft het kindje, wit en recht,

Uit ‘t wiegje in een kleine kist gelegd,

En wit en zwart, o simpel onderscheid,

Zijn slaap en dood, zijn tijd en eeuwigheid.

Hij is hier maar even geweest.

Men gaf hem op ‘t geboortefeest

Van hand tot hand, tot, stil en lief,

Een gast hem kussend aan de lippen hief.

En allen keken. later is gezegd:

Hij gaf een zuiver klein geluid,

Verschrikt en schoon, zooals een nieuwe fluit,

Die men probeert en peinzend nederlegt.

Willem de Mérode

Sedert de zestiende eeuw zijn geschilderde en getekende portretten van opgebaarde doden bekend, in het begin als recht voorbehouden aan vorsten, adel en clerus. Het vroegste voorbeeld in de Noordelijke Nederlanden is het schilderij waarop de doodgeschoten Willem van Oranje staat afgebeeld. Na de moordaanslag door Balthasar Gerards op 10 juli 1584 in de Prinsenhof te Delft, lag Willem van Oranje lange tijd opgebaard, zodat de begrafenis geregeld kon worden en het volk afscheid van hem nemen kon. Sommigen wilden een beeltenis maken, maar dit was verboden uit angst dat zijn vijanden de kans zouden benutten om de dode te bespotten met ongepaste prenten. Eén man echter maakte wel schetsen van de overleden prins. Of hij hiermee het verbod van de Staten-Generaal trotseerde, of dat hij als enige toestemming ervoor had verkregen, is onbekend. Hoe dan ook, deze Christiaen Jansz. van Bieselingen schilderde op grond van zijn schetsen twee haast identieke schilderijtjes van de opgebaarde prins. Deze doodsportretten worden in Delft (in de Prinsenhof, tegenover de kogelgaten) en Zaltbommel bewaard.

De oudste zoon van Willem van Oranje, Filips Willem, werd op zijn praalbed, omgeven door treurenden, afgebeeld op een (anoniem) schilderij. Hij stierf te Brussel op 21 februari 1618. Een aantal jaren later overleed de tweede zoon van Willem van Oranje, prins Maurits. Hij werd in april 1625 op zijn doodsbed geschilderd door A.P. van de Venne. Dit betreffende de eerste, bekende doodsportretten van leden van het huis Oranje-Nassau.

Eveneens in de zestiende eeuw ontstond in (nota bene) Vlaanderen het genre van kinderen op hun doodsbedje. Het overgrote deel van nog bestaande afbeeldingen van opgebaarde kinderen stamt echter uit de Noorderlijke Nederlanden en wel uit de eeuw daarop. Vaak zijn de kinderen versierd met gevlochten kransen, soms heeft het kind een bloem of boeketje in de hand. Dit gebruik heeft tot in onze dagen stand gehouden, zoals op een aantal van de hierin opgenomen foto’s te zien is.

In de loop van deze zeventiende eeuw liet ook de hogere burgerij zich meer en meer voor de eeuwigheid afbeelden. Het doodsportret, ofwel het post mortem portret, verspreidde zich op de duur vanuit de kerk naar half openbare ruimten als de pastorie (geestelijken) en naar de particuliere woning (burgers).

Uit de achttiende eeuw zijn nauwelijks doodsportretten overgeleverd. Het was de tijd van de rationele en op vooruitgang gerichte Verlichting, waarbij de dood meer een randverschijnsel werd. Letterlijk in de zin dat uit het oogpunt van hygiëne (ook een ideaal van de Verlichting) begraafplaatsen buiten de bebouwde kom aangelegd dienden te worden; het kerkhof verdween uit het centrum van de gemeenschap.

Uit het begin van de negentiende eeuw dateert in onze contreien het dodenmasker. Niet alleen het gezicht, maar ook handen van bijzondere personen werden afgegoten in gips, brons of marmer. Momenteel zijn er bijna dertig exemplaren van Nederlandse dodenmaskers bekend.

Onder invloed van de romantiek won ook het doodsportret weer terrein, zeker toen omstreeks 1850 de fotografie zijn intrede deed. Direct al bij de komst van het daguerrotype nam deze post mortem fotografie een hoge vlucht. De foto’s kwamen in het familie-album terecht of werden verwerkt in een medaillon. Ook het carte de visite-portret en het bidprentje memoreerden niet zelden de trekken van de beminde dode kort na zijn stervensuur.

Bij dit alles blijkt het funeraire kinderportret het meest voor te komen. Met andere woorden: juist overleden kinderen werden op een post mortem foto afgebeeld, niet in de laatste plaats omdat vaak een afbeelding van het gestorven kind tijdens zijn of haar leven ontbrak.

De algemene acceptatie van post-mortem fotografie in de negentiende eeuw blijkt duidelijk uit allerlei bewaard gebleven opnames van vooraanstaande of minder bekende doden. Uit de rouwcultus rondom de leden van het koninklijk huis stammen diverse doodsportretten in gravure of lithografie. Ze waren verkrijgbaar voor het grote publiek. Dit gold bijvoorbeeld voor een portret van de op 3 juni 1877 gestorven koningin Sophie van Wurtemberg, eerste gemalin van koning Willem III. Zij werd op haar doodsbed gefotografeerd en de afdrukken van deze opname waren te koop. Zoiets zou nu ondenkbaar zijn.

Een ander voorbeeld. In 1866 verscheen in Utrecht het curieuze boekje ‘May‘ uitgegeven door de ouders van May Twist die in 1866 op zesjarige leeftijd overleed. Het is een kleine dichtbundel met als frontispice een post-mortem foto van het meisje. Toen zij op 30 mei 1866 stierf lieten haar ouders dit boekje uitgeven. Naast Nederlandse, Engelse en Franse gedichten over het sterven van kinderen – in die jaren van cholera-epidemieën een algemeen verschijnsel – werden ook May’s laatste woorden opgetekend.

Zoals gezegd, de confrontatie met een dode was in die tijd algemeen geaccepteerd. De rouwcultus van de late negentiende eeuw verwachtte zelfs van de nabestaanden dat die een souvenir van de dierbaar gestorvenen bij zich droegen of wegschonken. Natuurlijk was het dragen van portretten in medaillons, in armbanden en kettingen niet alleen de rouwenden voorbehouden. In de reeks verliefd, verloofd, getrouwd behoorde (en behoort) het fotoportret tot de amoureuze parafernalia. Echter in combinatie met haarlokken en haarwerken krijgt het een ‘zwaarder’ accent. De haarfestisj vormde niet alleen in een specifiek element in het amoureuze verkeer, maar ook in de doodscultus. Medaillons waarin verwerkt afgeknipte lokken van de dierbare, sieraden uit haar gevlochten, schilderijtjes van haar gemaakt, het waren vooral producten van huisvlijt, maar deze zogeheten rouwhaarwerken konden ook op bestelling worden geleverd.

Aan het begin van de twintigste eeuw werden post mortem foto’s gebruikt om in een plaquette – een mechanische montage op bijvoorbeeld emaille of porselein – op een grafsteen verwerkt te worden. Dit gebruik blijkt net over de grens met België tot voor kort een welhaast bloeiend bestaan geleid te hebben.

Op het Oude Kerkhof aan de Kwakkelstraat te Turnhout wemelt het van deze plaquettes ofwel portret-medaillons. Vele graven zijn er mee getooid, sommige dragen kleine trossen: vier of zes medaillons aan een graf ("Begraafplaats van de familie…") zijn geen uitzondering. De meeste opnamen zijn bij leven genomen, maar op een significant aantal foto’s zijn de doden reeds dood. Tweemaal dood zou je kunnen zeggen: opgebaard (post mortem gefotografeerd en bevestigd aan het grafmonument) en daadwerkelijk in het graf gelegd..

Daarbij betreft het in de meeste gevallen medaillons met overleden kinderen, hier dus ook veruit de meest voorkomende categorie. Ik kende post mortem foto’s van kinderen wel, vooral via boeken, maar nog nooit had ik zulke opnamen in zo’n grote getale op een begraafplaats gezien – in de buitenlucht dus

In 1990 is over deze rustplaats een boek verschenen, onder de titel ‘Elks deel op ‘t laatste is het graf. Een Turnhouts verhaal over begraven en het oude kerkhof‘ van de hand van H. de Kok en E. Wauters. In dit boek wordt opmerkelijk genoeg geen enkele melding van dit fotografisch fenomeen gemaakt. Was het dan zó veel voorkomend in België? Of was het juist voor deze streek, of zelfs: voor deze stad, voor deze dodenakker, usance? Dit laatste wordt namelijk versterkt door enkele naamsvermeldingen op de rand van een aantal medaillons; hoogstwaarschijnlijk betreft het de namen van Turnhoutse fotozaken. Met als specialisatie het ensceneren van een ontroerend tafereel: een pas gestorven kind, gekleed in een wit doodskleedje, op een bedje gelegd, vaak getooid met bloemen, soms met een rozenkrans in de handjes. Vervolgens op de gevoelige plaat vastleggen en de opname mechanisch verwerken in een porseleinen medaillon.

De portretten werden vervaardigd vanaf de jaren dertig van de vorige eeuw, met een opvallende piek in de oorlogsjaren 1941 en 1942, maar ik ontdekte ook een medaillon die gemaakt bleek in het begin van de jaren zeventig. Zo kort geleden!

Alle hierna opgenomen foto’s zijn gemaakt op één dag – zondag 4 januari 2004 – en op hetzelfde kerkhof: het Oude Kerkhof aan de Kwakkelstraat te Turnhout, België. Het is een selectie. De opnamen zijn zonder tekst (geen naam, geen jaartal, geen familieleden) en ze zijn niet chronologisch opgenomen. Anders gezegd: het gaat alleen om de opname, om het post mortem fotomedaillon, een curieus cultuurhistorisch fenomeen.

Het zijn bijzondere foto’s van over de grens.

Geraadpleegde literatuur:

Boudewijn Büch: ‘Kindergraven in Nederland’, in: Maatstaf 1983/2.

Diversen: ‘Postume Portretten’, special Kunstschrift 1997/4.

H. de Kok, E. Wauters: Elks deel op ‘t laatste is het graf. Een Turnhouts verhaal over begraven en het oude kerkhof (Dienst Stadspromotie en Geschiedkundige Kring Taxandria, Turnhout, 1990).

C. Leeflang (samenstelling, inleiding): De dichter en de dood. Een bundel doodenlyriek (Utrecht, 1946).

Cees van Raak: Vorstelijk begraven en gedenken. Funeraire geschiedenis van het huis Oranje-Nassau (Thoth, Bussum, 2003).

B.C. Sliggers (eindredactie): Naar het lijk. Het Nederlandse doodsportret 1500-heden (Teylers Museum, Haarlem, 1998).

D. Snoep: ”k Zal eeuwig U beminnen, eeuwig U waarderen En in gedagten dagelyks met U verkeeren’, in: Kunstschrift 1985/3.

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Cees van Raak, Galerie des Morts, Raak, Cees van

.jpg)

Johann Wilhelm Ludwig Gleim

(1719-1803)

Das Blümchen

Da steht im Gras’ ein Blümchen schön;

Sieh’s an, sieh’s an, es lässt sich sehn,

Ein blau schön Blümchen, zart und fein;

Kein Blümchen wol mag schöner seyn!

Sieh’s an, sieh’s an, es spricht mit dir:

»Schön Mädchen du, bleib doch bei mir!«

Schön Mädchen geht, das Blümchen spricht:

»Schön Mädchen, ach! vergiß mein nicht!«

Hans Hermans Natuurdagboek Juni 2010

Photos: Hans Hermans – Gedicht :Johann Wilhelm Ludwig Gleim

► Website Hans Hermans Fotografie

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Archive G-H, Hans Hermans Photos, MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY - department of ravens & crows, birds of prey, riding a zebra, spring, summer, autumn, winter

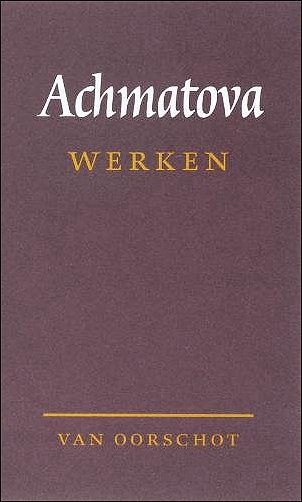

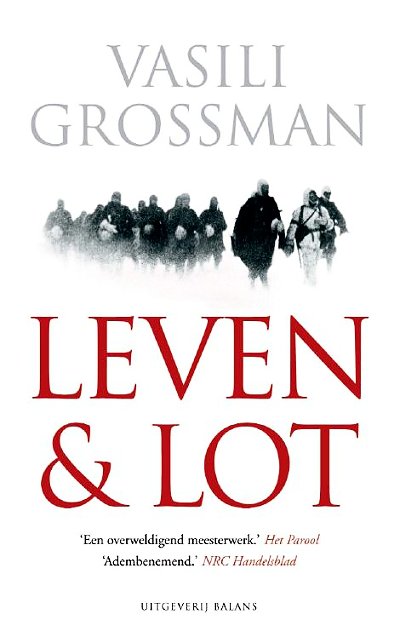

Russische vertaalprijs

voor Nederlandse Vertalingen

Het Internationale Vertaalcentrum voor Russische literatuur, een onderdeel van de Russische Academie van Wetenschappen te Sint Petersburg, is dit jaar in het buitenland op zoek gegaan naar de beste vertalingen van Russische literatuur. Voor het concours kwamen literaire vertalingen in alle talen in aanmerking, mits gepubliceerd in de afgelopen drie jaar (2007 t/m 2009).

De jury koos in maar liefst twee van de vier categorieën voor een Nederlandse winnaar.

In de categorie ‘poëzie’ won het vertalersduo Margriet Berg en Marja Wiebes met hun vertaling Werken van Anna Achmatova (uitgeverij Van Oorschot). Deze tweetalige uitgave in de Russische Bibliotheek bevat een ruime selectie van meer dan driehonderd gedichten, die door de vertalers tevens van aantekeningen en een nawoord werden voorzien. Froukje Slofstra won in de categorie ‘debuutvertalingen proza’ met haar vertaling Leven & lot van Vasili Grossman (uitgeverij Balans). De vertaalster verzorgde tevens een uitgebreid nawoord bij Grossmans roman, die in 1961 door de KGB in beslag werd genomen, pas twintig jaar later kon worden gepubliceerd en inmiddels als een twintigste-eeuwse klassieker geldt.

De totstandkoming van beide vertalingen werd door het Nederlands Letterenfonds ondersteund met werkbeurzen voor de vertalers.

De uitreiking van de prijzen vindt op 1 juli plaats in Sint Petersburg tijdens een plechtige ceremonie in het Instituut voor Russische Literatuur (Poesjkinhuis) in aanwezigheid van de leden van een internationale raad van experts. Alle winnaars worden beloond met geldprijzen.

Bron: Nederlands Letterenfonds

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Achmatova, Anna, POETRY ARCHIVE

Albert Verwey

(1865 – 1936)

Ik heb mijn hart ú tot een huis gewijd

Ik heb mijn hart ú tot een huis gewijd,

En midden in het binnenst heiligdom,

Waar de outerkaars in ‘t donker gloeit, verbeid

Ik u, mijn lief, mijn zoet sieraad alom!

Ik sloeg mijn ziel dit zoete donker om,

Alleen om ú te ontmoeten, die me altijd

Belooft te komen, in ‘t geheim, na stom

Eerbiedig beiden eenen kleinen tijd.

O kom, mijn lief, die nog zoo verre staat…

‘k Verwacht in ‘t donker ginds uw licht gelaat…

Ik-zelf ben een visioen van nacht en gloed!

O kom, mijn zoete Gloed, mijn sombre Nacht!

‘t Mysterie is ondoofbaar, – doch ik wacht

Met beving, daar ik eenmaal sterven moet.

Albert Verwey gedicht

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Archive U-V

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature