Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

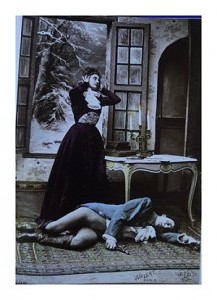

The Sorrows of Young Werther (56) by J.W. von Goethe

DECEMBER 15.

What is the matter with me, dear Wilhelm? I am afraid of myself! Is not

my love for her of the purest, most holy, and most brotherly nature? Has

my soul ever been sullied by a single sensual desire? but I will make no

protestations. And now, ye nightly visions, how truly have those mortals

understood you, who ascribe your various contradictory effects to some

invincible power! This night I tremble at the avowal–I held her in my

arms, locked in a close embrace: I pressed her to my bosom, and covered

with countless kisses those dear lips which murmured in reply soft

protestations of love. My sight became confused by the delicious

intoxication of her eyes. Heavens! is it sinful to revel again in such

happiness, to recall once more those rapturous moments with intense

delight? Charlotte! Charlotte! I am lost! My senses are bewildered, my

recollection is confused, mine eyes are bathed in tears–I am ill; and

yet I am well–I wish for nothing–I have no desires–it were better I

were gone.

Under the circumstances narrated above, a determination to quit

this world had now taken fixed possession of Werther’s soul. Since

Charlotte’s return, this thought had been the final object of all his

hopes and wishes; but he had resolved that such a step should not be

taken with precipitation, but with calmness and tranquillity, and with

the most perfect deliberation.

His troubles and internal struggles may be understood from the following

fragment, which was found, without any date, amongst his papers, and

appears to have formed the beginning of a letter to Wilhelm.

“Her presence, her fate, her sympathy for me, have power still to

extract tears from my withered brain.

“One lifts up the curtain, and passes to the other side,–that is

all! And why all these doubts and delays? Because we know not what is

behind–because there is no returning–and because our mind infers that

all is darkness and confusion, where we have nothing but uncertainty.”

His appearance at length became quite altered by the effect of his

melancholy thoughts; and his resolution was now finally and irrevocably

taken, of which the following ambiguous letter, which he addressed to

his friend, may appear to afford some proof.

The Sorrows of Young Werther (Die Leiden des jungen Werther) by J.W. von Goethe. Translated by R.D. Boylan.

To be continued

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: -Die Leiden des jungen Werther, Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von

Renée Vivien

(1877-1909)

Je t’aime d’être faible…

Je t’aime d’être faible et câline en mes bras

Et de chercher le sûr refuge de mes bras

Ainsi qu’un berceau tiède où tu reposeras.

Je t’aime d’être rousse et pareille à l’automne,

Frêle image de la Déesse de l’automne

Que le soleil couchant illumine et couronne.

Je t’aime d’être lente et de marcher sans bruit

Et de parler très bas et de haïr le bruit,

Comme l’on fait dans la présence de la nuit.

Et je t’aime surtout d’être pâle et mourante,

Et de gémir avec des sanglots de mourante,

Dans le cruel plaisir qui s’acharne et tourmente.

Je t’aime d’être, ô soeur des reines de jadis,

Exilée au milieu des splendeurs de jadis,

Plus blanche qu’un reflet de lune sur un lys…

Je t’aime de ne point t’émouvoir, lorsque blême

Et tremblante je ne puis cacher mon front blême,

Ô toi qui ne sauras jamais combien je t’aime !

Renée Vivien poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive U-V, Renée Vivien, Vivien, Renée

Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven

(1874 – 1927)

SIMILARITY

CIVIL LAWS PRESSURE BY MEANS OF INTIMIDATION

FOR RETRIBUTION OF “WRONG”

IS BLACKMAILS IDENTICAL ACTION

TO CONINUE VIBRATINGLY GYRATING

EVOLUTION PROCESS’

PERPETUUM MOBILE.

ALL LIFE – SAVAGE – CIVILIZED IS BASED ON

IMMORTAL MOVEMENT

OF FORCE – CONTRAFORCE –

EACH IN RIGHT OF EIXTENCE –

EACH IN HOSTILE RELATIONSHIPS’ FAMILYFEUD –

INTERMINGLING – TO MERGE INTO STATE.

SOCIETY –

UNDERWORLD ACT FROM JUST PRINCIPLE OF

SELF PRESERVATION TO

– IN VAIN –

ANNIHILATE EACH OTHER –

FINALLY TO EMBRACE –

UNEHTICAL –

FOR UTILITY.

ETHICS IS SOCIETY’S AS UNDERWORLD’S

DIPLOMATIC MEANS TO

INSURE SAFETY’ –

EQUALLY ABANDONNED AS SENTIMENTAL SECOND

FOR DYNAMIC PRINCIPALITY:

EXPANSION.

AS FOAVRO SMILES – UNDERWORLD EMERGES SOCIETY UP –

BY REVERSE – SOCIETY PLUNGES UNDER.

SIMILAR METHODS DIFFER ON SURFACE

BY CONVENTIONS’ TIMEIMPOSED

LAWAPPLICATION LEGALIZED BY FORCE – VICTOR –

CRIMINAL – CRIMINAL VICTORIOUS –

RULER BY GRACE OF POWER –

BOMBASTICALLY PROCLAIMING EVERBOYD’S LAW

LAWFUL-L- FOR BUT HIS PARTY.

(MUSSOLINI.)

ALL IS IDENTICAL

PIOUS POMP – SOLEMN MUMMERY – GRACEFUL GESTURE –

RESPLENDENT VARNISH –

HYPOCRITICAL FIDDLESTICKS OF SOCIETY –

AS UNDERWORLD’S UNADORNED HONESTY

BUT THROB OF BASIC PRINCIPLE:

ROTATION.

E.V.F.L

Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive E-F, Dada, Freytag-Loringhoven, Elsa von

Klankpoëzie, performance poëzie en visuele poëzie bij Underground Poetry Fest Jette (B)

Klankpoëzie, performance poëzie en visuele poëzie bij Underground Poetry Fest Jette (B)

Van vrijdag 19 tot en met zondag 21 september 2014 is Jette een weekend lang de internationale bakermat van de experimentele poëzie. U wordt meegevoerd naar de wereld van klankpoëzie, performance poëzie en visuele poëzie en overdonderd je met performances, tentoonstellingen, conferenties en workshops voor groot en klein.

Vrijdag start met een academische zitting over experimentele poëzie en opent de tentoonstelling met werk van visuele poëten. ’s Avonds is de avant-première van This is Belgian Chocolate van Philip Meersman. Zaterdag volgt de wonderlijke Dada-wereld van Maintenant #8 met Three Rooms Press uit New York en zondag wordt afgesloten met een Publiek Gedicht, de wereldberoemde Alain Arias-Misson trekt met een karavaan dichters door Jette en proclameert Het Onverenigd Koninkrijk België.

PROGRAMMA

Vrijdag 19/09 om 20.00 uur: lancering “This Is Belgian Chocolate” van Philip Meersman

Zaterdag 20/09 om 19.00 uur: lancering Maintenant #8 door Three Rooms Press

Zondag 21/09 om 10.00 uur: Het Onverenigd Koninkrijk België, een Publiek Gedicht door Alain Arias-Misson

Doorlopend: unieke expo concrete & visuele poëzie

WORKSHOPS

Zaterdag 20/9: 14.00 – 17.00

“poetry and performance” voor leerlingen van het secundair onderwijs in het Frans en Engels (door Slam Tribu). Meebrengen: pen en papier.

“Mysterieuze doos: een workshop visuele en sonore poëzie” voor kinderen uit het lager onderwijs (9-12 jaar) (concept: Maja Jantar)

Zondag 21/9: 10.00-12.00

“Graphic poetry” voor kinderen uit het lager onderwijs (6-9 jaar) (door Lies Van Gasse)

# Meer informatie op website Underground Poetry Fest

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: #Archive Concrete & Visual Poetry, #More Poetry Archives, Art & Literature News, Dada, EXPERIMENTAL POETRY, FLUXUS LEGACY, Poetry Slam

Anna de Noailles

(1876-1933)

La vie profonde

Être dans la nature ainsi qu’un arbre humain,

Étendre ses désirs comme un profond feuillage,

Et sentir, par la nuit paisible et par l’orage,

La sève universelle affluer dans ses mains !

Vivre, avoir les rayons du soleil sur la face,

Boire le sel ardent des embruns et des pleurs,

Et goûter chaudement la joie et la douleur

Qui font une buée humaine dans l’espace !

Sentir, dans son coeur vif, l’air, le feu et le sang

Tourbillonner ainsi que le vent sur la terre.

– S’élever au réel et pencher au mystère,

Être le jour qui monte et l’ombre qui descend.

Comme du pourpre soir aux couleurs de cerise,

Laisser du coeur vermeil couler la flamme et l’eau,

Et comme l’aube claire appuyée au coteau

Avoir l’âme qui rêve, au bord du monde assise…

Anna de Noailles poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive M-N, Noailles, Anna de

32ste Nacht van de Poëzie TivoliVredenburg Utrecht op 20 september 2014

Rufus Wainwright op de 32ste Nacht van de Poëzie: De wereldberoemde singer-songwriter Rufus Wainwright  treedt op zaterdag 20 september op tijdens de 32ste Nacht van de Poëzie in TivoliVredenburg. Michaël Stoker, organisator van De Nacht: “We zijn ontzettend trots op dit optreden. Zijn vader Loudon Wainwright III heeft in 1992 ook opgetreden tijdens de Nacht van de Poëzie. Toen ik dat aan Rufus mailde en bleek dat het in zijn tourschema paste, wilde hij graag in de voetsporen van zijn vader treden. Een mooier programma kunnen we ons niet wensen, nu we voor het eerst weer terugkeren in de Grote Zaal van Vredenburg.”

treedt op zaterdag 20 september op tijdens de 32ste Nacht van de Poëzie in TivoliVredenburg. Michaël Stoker, organisator van De Nacht: “We zijn ontzettend trots op dit optreden. Zijn vader Loudon Wainwright III heeft in 1992 ook opgetreden tijdens de Nacht van de Poëzie. Toen ik dat aan Rufus mailde en bleek dat het in zijn tourschema paste, wilde hij graag in de voetsporen van zijn vader treden. Een mooier programma kunnen we ons niet wensen, nu we voor het eerst weer terugkeren in de Grote Zaal van Vredenburg.”

Rufus Wainwright staat bekend als één van de belangrijkste songwriters van deze tijd. Volgens Elton John is hij ‘the greatest songwriter on the planet’. Hij komt exclusief voor ‘de Nacht’ naar Nederland.

Het is onderdeel van de jarenlange Nacht-traditie dat muzikanten en andere artiesten als entr’actes enkele malen het stokje van de dichters overnemen tijdens de poëziemarathon. Andere acts zijn de Ashton Brothers, Maarten Heijmans zingt Shaffy, pianiste Daria van den Bercken en het negenkoppige tango-orkest Orquesta Típica Andariega.

Het is onderdeel van de jarenlange Nacht-traditie dat muzikanten en andere artiesten als entr’actes enkele malen het stokje van de dichters overnemen tijdens de poëziemarathon. Andere acts zijn de Ashton Brothers, Maarten Heijmans zingt Shaffy, pianiste Daria van den Bercken en het negenkoppige tango-orkest Orquesta Típica Andariega.

De dichterslijst van De Nacht is compleet. Dichters Andy Fierens, Jan Glas, Erik Jan Harmens, Florence Tonk en Max Temmerman zijn toegevoegd aan de in totaal 21 dichters die gaan optreden. Piet Piryns en Ester Naomi Perquin verzorgen de presentatie.

De gangen rond de Grote Zaal worden bezet door een boekenmarkt. Niet alleen kan men hier de bundels laten signeren, ook is daar gelegenheid tot eten en drinken. Alle bezoekers krijgen de exclusieve Nachtbundel, met daarin veel ongepubliceerd werk van de dichters.

Volledige dichterslijst: Wim Brands, Remco Campert, Bart Chabot, Andy Fierens, Jan Glas, Maarten van der Graaff, Erik Jan Harmens, Marjolijn van Heemstra , Judith Herzberg, Ingmar  Heytze, Anton Korteweg, Els Moors, Leonard Nolens, Jean Pierre Rawie, Mustafa Stitou, Florence Tonk, Max Temmerman, Maud Vanhauwaert, Miriam Van hee, Menno Wigman & Kira Wuck.

Heytze, Anton Korteweg, Els Moors, Leonard Nolens, Jean Pierre Rawie, Mustafa Stitou, Florence Tonk, Max Temmerman, Maud Vanhauwaert, Miriam Van hee, Menno Wigman & Kira Wuck.

Entr’actes: Rufus Wainwright, De Ashton Brothers, Orquesta Típica Andariega, Maarten Heijmans zingt Ramses Shaffy, Daria van den Bercken.

32ste Nacht van de Poëzie

Zaterdag 20 september 2014

20.00 – ±03.00 uur

TivoliVredenburg, Utrecht

Meer informatie op website www.nachtvandepoezie.nl

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Art & Literature News, MUSIC, Nacht van de Poëzie, Rufus Wainwright, THEATRE, Wuck, Kira

Op woensdag 17 september is, als onderdeel van het Incubate-Festival, de Stedelijke Finale van de Tilburgse Poetry Slam Podiumvlees in de kleine zaal van De NWE Vorst. Tijdens deze Poetry Slam gaan de winnaars van de vier voorrondes de poëtische strijd met elkaar aan. Ook presenteert Podiumvlees, in samenwerking met uitgeverij teleXpress, tijdens de Stedelijke Finale de eerste overzichtsbundel. In deze bundel staat werk van alle dichters die het afgelopen seizoen meegedaan hebben aan Podiumvlees. De Finale van Podiumvlees vindt op woensdag 17 september vanaf 20.00 uur plaats in de kleine zaal van De NWE Vorst. De toegang is gratis.

Op woensdag 17 september is, als onderdeel van het Incubate-Festival, de Stedelijke Finale van de Tilburgse Poetry Slam Podiumvlees in de kleine zaal van De NWE Vorst. Tijdens deze Poetry Slam gaan de winnaars van de vier voorrondes de poëtische strijd met elkaar aan. Ook presenteert Podiumvlees, in samenwerking met uitgeverij teleXpress, tijdens de Stedelijke Finale de eerste overzichtsbundel. In deze bundel staat werk van alle dichters die het afgelopen seizoen meegedaan hebben aan Podiumvlees. De Finale van Podiumvlees vindt op woensdag 17 september vanaf 20.00 uur plaats in de kleine zaal van De NWE Vorst. De toegang is gratis.

In de eerste Stedelijke Finale van Podiumvlees gaan Romano Unheard, Nathalie van Meurs (foto), Hans d’Olivat en Josse Kok de strijd aan. Op het spel staat een plaats in het Nederlands Kampioenschap Poetry Slam, dat in januari 2015 gehouden wordt in Utrecht. De dichters worden beoordeeld door een vakjury en een publieksjury. De vakjury bestaat in ieder geval uit dichter Daan Doesborgh (winnaar NK Poetry Slam 2010) en Ernest Potters van Uitgeverij teleXpress.

Naast de dichters die optreden in de slam zullen ook dichters uit de verschillende Nederlandse Poetry Circles acte de presence geven. D.J. Levi van Huijgevoort en Meandertaler verzorgen de muziek tijdens de Finale.

Naast de dichters die optreden in de slam zullen ook dichters uit de verschillende Nederlandse Poetry Circles acte de presence geven. D.J. Levi van Huijgevoort en Meandertaler verzorgen de muziek tijdens de Finale.

Podiumvlees is een initiatief van de Tilburgse slamdichters Martin Beversluis en Daan Taks. Zij gaan ook komend seizoen door met het organiseren van Podiumvlees. Daarom is Podiumvlees nog altijd op zoek naar nieuwe deelnemers. Wie meer informatie wil, kan op facebook terecht: www.facebook.com/podiumvlees

Incubate presenteert: Finale Podiumvlees Poetry Slam in De NWE Vorst Tilburg op woensdag 17 september 2014

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: #More Poetry Archives, Art & Literature News, Beversluis, Martin, Poetry Slam

Hans Leybold

(1892-1914)

Auch ein Nekrolog

für Christian Morgenstern

O Christian, wir glätten weinend unsre Bügelfalten:

auf Feuerleitern krochen wir mit dir in rhythmische Gerüste.

Mit dem Zement der Ironie ausfülltest du die Spalten

vermorschter Traditionen Mauer. O metaphysisches Gelüste.

O Huhn und Bahnhofshalle! Weit entfernte Latten!

Ihr Wiesel, Kiesel, mitten mang det Bachjeriesel!

Palmström, du ohngeschneuzter, den sie kastrieret hatten!

Genosse Korf, du nie banaler Wennschon – Stiesel!

(Verzeiht den Kitschton. Mich übermannte hier die Rührung.

Verzeih besonders du, Kollege Untermstriche:

schon hab ich in der harten Hand der Verse Führung

wieder; und komme mir auf meine Schliche.) –

Nun quäkt der Turmhahn geil auf Staackmanns Miste

sein Kikriki, und ist bald Ernst, bald Otto.

Verleger reißen sich die Haare aus, als ob das müßte,

und spielen mit der Perioden-Presse trotzdem Lotto.

O Christian: wie später Gotik wandgeklatschter Freske

(im spitzen Reigen härmender sebastianischer Figuren):

du paßtest nicht in unsren Krämerkram, du fleischgewordene Groteske;

nicht schmiegte sich dein edler Vollbart in die Schöße unsrer Huren!

Das Literatenleben, o du mein Christian, ist doch nicht besser

als das ärarische. (Sie dichten zur Musik von Walter Kollo!)

Wir tanzen zwischen Film und Feuilleton auf scharfem Messer . . .

Freu dich! Sei tot! Grüß mir, im Glanz geölter Locken, den Apollo!

Hans Leybold poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: *War Poetry Archive, Archive K-L, Hans Leybold, Leybold, Hans

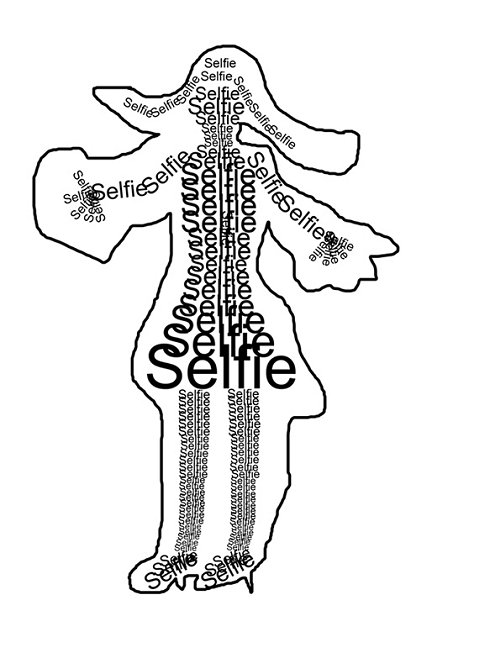

freda kamphuis ©2014:

selfie met omtrek

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: *Concrete + Visual Poetry K-O, Freda Kamphuis, Kamphuis, Freda

Voltaire

(1694-1778)

À Madame de Fontaine-Martel

Ô très singulière Martel,

J’ai pour vous estime profonde ;

C’est dans votre petit hôtel,

C’est sur vos soupers que je fonde

Mon plaisir, le seul bien réel

Qu’un honnête homme ait en ce monde.

Il est vrai qu’un peu je vous gronde ;

Mais, malgré cette liberté,

Mon cœur vous trouve, en vérité,

Femme à peu de femmes seconde ;

Car sous vos cornettes de nuit,

Sans préjugés et sans faiblesse,

Vous logez esprit qui séduit,

Et qui tient fort à la sagesse.

Or votre sagesse n’est pas

Cette pointilleuse harpie

Qui raisonne sur tous les cas,

Et qui, triste sœur de l’Envie,

Ouvrant un gosier édenté,

Contre la tendre volupté

Toujours prêche, argumente et crie

Mais celle qui si doucement,

Sans efforts et sans industrie,

Se bornant toute au sentiment,

Sait jusqu’au dernier moment

Répandre un charme sur la vie.

Voyez-vous pas de tous côtés

De très décrépites beautés,

Pleurant de n’être plus aimables,

Dans leur besoin de passion

Ne pouvant rester raisonnables,

S’affolier de dévotion,

Et rechercher l’ambition

D’être bégueules respectables ?

Bien loin de cette triste erreur,

Vous avez, au lieu de vigiles,

Des soupers longs, gais et tranquilles ;

Des vers aimables et faciles,

Au lieu des fatras inutiles

De Quesnel et de le Tourneur ;

Voltaire, au lieu d’un directeur ;

Et, pour mieux chasser toute angoisse,

Au curé préférant Campra,

Vous avez loge à l’opéra

Au lieu de banc dans la paroisse :

Et ce qui rend mon sort plus doux,

C’est que ma maîtresse, chez vous,

La liberté, se voit logée ;

Cette liberté mitigée,

À l’œil ouvert, au front serein,

À la démarche dégagée,

N’étant ni prude, ni catin,

Décente, et jamais arrangée ;

Souriant d’un souris badin

À ces paroles chatouilleuses

Qui font baisser un œil malin

À mesdames les précieuses.

C’est là qu’on trouve la gaîté,

Cette sœur de la liberté,

Jamais aigre dans la satire,

Toujours vive dans les bons mots,

Se moquant quelquefois des sots,

Et très souvent, mais à propos,

Permettant au sage de rire.

Que le ciel bénisse le cours

D’un sort aussi doux que le vôtre !

Martel, l’automne de vos jours

Vaut mieux que le printemps d’une autre.

Voltaire poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive U-V, MONTAIGNE, Voltaire

The Sorrows of Young Werther (55) by J.W. von Goethe

DECEMBER 12.

Dear Wilhelm, I am reduced to the condition of those unfortunate

wretches who believe they are pursued by an evil spirit. Sometimes I am

oppressed, not by apprehension or fear, but by an inexpressible internal

sensation, which weighs upon my heart, and impedes my breath! Then

I wander forth at night, even in this tempestuous season, and feel

pleasure in surveying the dreadful scenes around me.

Yesterday evening I went forth. A rapid thaw had suddenly set in: I

had been informed that the river had risen, that the brooks had all

overflowed their banks, and that the whole vale of Walheim was under

water! Upon the stroke of twelve I hastened forth. I beheld a

fearful sight. The foaming torrents rolled from the mountains in the

moonlight,–fields and meadows, trees and hedges, were confounded

together; and the entire valley was converted into a deep lake, which

was agitated by the roaring wind! And when the moon shone forth, and

tinged the black clouds with silver, and the impetuous torrent at

my feet foamed and resounded with awful and grand impetuosity, I was

overcome by a mingled sensation of apprehension and delight. With

extended arms I looked down into the yawning abyss, and cried,

“Plunge!'” For a moment my senses forsook me, in the intense delight of

ending my sorrows and my sufferings by a plunge into that gulf! And then

I felt as if I were rooted to the earth, and incapable of seeking an end

to my woes! But my hour is not yet come: I feel it is not. O Wilhelm,

how willingly could I abandon my existence to ride the whirlwind, or to

embrace the torrent! and then might not rapture perchance be the portion

of this liberated soul?

I turned my sorrowful eyes toward a favourite spot, where I was

accustomed to sit with Charlotte beneath a willow after a fatiguing

walk. Alas! it was covered with water, and with difficulty I found even

the meadow. And the fields around the hunting-lodge, thought I. Has our

dear bower been destroyed by this unpitying storm? And a beam of past

happiness streamed upon me, as the mind of a captive is illumined by

dreams of flocks and herds and bygone joys of home! But I am free from

blame. I have courage to die! Perhaps I have,–but I still sit here,

like a wretched pauper, who collects fagots, and begs her bread from

door to door, that she may prolong for a few days a miserable existence

which she is unwilling to resign.

The Sorrows of Young Werther (Die Leiden des jungen Werther) by J.W. von Goethe. Translated by R.D. Boylan.

To be continued

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: -Die Leiden des jungen Werther, Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von

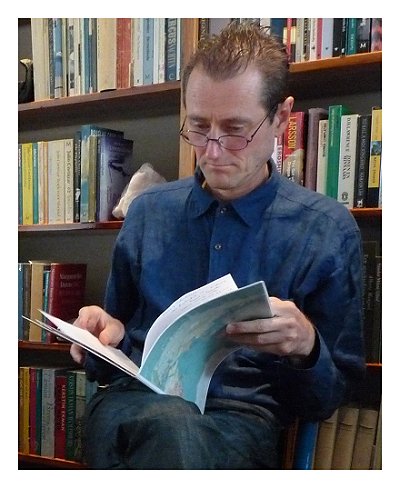

K. Michel (photo j. v. Kempen)

K. Michel

Voorop

voorop

zwemt een piepklein visje

dat gevolgd wordt door

een iets minder klein visje

waarachter eentje

van dertien in een dozijn zwemt

met in zijn spoor

een wat lijviger type

dat op de hielen wordt gezeten door

een tamelijk fors exemplaar

waarvan de sierlijke vinnen overigens

aan zomerjurkjes doen denken

deze nu wordt geschaduwd door

een ronduit groot te noemen vis

die op zijn bek

lorgnetvormige sprieten draagt

als een oude kassier

met in zijn kielzog echt een kanjer

ruw geschat groter

dan een torpedo kleiner

dan een rondvaartboot

maar wel met een spuitgat op zijn kop

en als iedereen dan eindelijk

keurig op een rij zwemt

gestreept gevlekt gespikkeld grijs groenblauw oranje smaragd

begint als door een onzichtbaar teken

– misschien doet de voorste wel blub –

van voor naar achteren het grote happen

C.P. Naudé (photo C. v.d. Walt)

Charl-Pierre Naudé

Voorpunt

aan die voorpunt

swem ʼn piepklein vissie

gevolg deur

ʼn ietwat minder klein vissie

en nog ene agter hom

ʼn valetjie in ʼn honderd

ʼn raps lywiger soort

wat op sy hoede geplaas word

deur ʼn taamlik forse eksemplaar

waarvan die sierlike vinne trouens

aan somerrokkies herinner

en dié se spoor word nougeset gehou

deur pront gestel ʼn volronde vis

wat sy spriete soos die briltoutjies

van ʼn ou kassiere dra

met in sy kielsog sowaar ʼn knewel

by skatting groter

as ʼn torpedo kleiner

as ʼn rondvaartboot

maar darem met ʼn spuitgat op die kroon

en as almal oplaas

behoorlik in ʼn ry swem –

gestreep gevlek bespikkel grys

akwamarien oranje smarag –

begin asof ʼn teken gegee is

– miskien ʼn bloep deur die voorswemmer –

van voor na agter

die groot gebytery

Zuid-Afrikaanse vertaling van het gedicht ‘Voorop’ van K. Michel door Charl-Pierre Naudé

In de serie Vertaalvrucht nr. 7

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive M-N, Charl-Pierre Naudé, K. Michel, Literaire Salon in 't Wevershuisje, Michel, K., Naudé, Charl-Pierre, VERTAALVRUCHT

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature