Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

Emily Dickinson

(1830-1886)

I n a L i b r a r y

A precious, mouldering pleasure ‘t is

To meet an antique book,

In just the dress his century wore;

A privilege, I think,

His venerable hand to take,

And warming in our own,

A passage back, or two, to make

To times when he was young.

His quaint opinions to inspect,

His knowledge to unfold

On what concerns our mutual mind,

The literature of old;

What interested scholars most,

What competitions ran

When Plato was a certainty.

And Sophocles a man;

When Sappho was a living girl,

And Beatrice wore

The gown that Dante deified.

Facts, centuries before,

He traverses familiar,

As one should come to town

And tell you all your dreams were true;

He lived where dreams were sown.

His presence is enchantment,

You beg him not to go;

Old volumes shake their vellum heads

And tantalize, just so.

.jpg)

k e m p i s p o e t r y m a g a z i n e

More in: Dickinson, Emily, Libraries in Literature

.jpg)

Der Kaufmann

Franz Kafka (1883-1924)

Es ist möglich, daß einige Leute Mitleid mit mir haben, aber ich spüre nichts davon. Mein kleines Geschäft erfüllt mich mit Sorgen, die mich innen an Stirne und Schläfen schmerzen, aber ohne mir Zufriedenheit in Aussicht zu stellen, denn mein Geschäft ist klein.

Für Stunden im voraus muß ich Bestimmungen treffen, das Gedächtnis des Hausdieners wachhalten, vor befürchteten Fehlern warnen und in einer Jahreszeit die Moden der folgenden berechnen, nicht wie sie unter Leuten meines Kreises herrschen werden, sondern bei unzugänglichen Bevölkerungen auf dem Lande. Mein Geld haben fremde Leute; ihre Verhältnisse können mir nicht deutlich sein; das Unglück, das sie treffen könnte, ahne ich nicht; wie könnte ich es abwehren! Vielleicht sind sie verschwenderisch geworden und geben ein Fest in einem Wirtshausgarten und andere halten sich für ein Weilchen auf der Flucht nach Amerika bei diesem Feste auf.

Wenn nun am Abend eines Werketages das Geschäft gesperrt wird und ich plötzlich Stunden vor mir sehe, in denen ich für die ununterbrochenen Bedürfnisse meines Geschäftes nichts werde arbeiten können, dann wirft sich meine am Morgen weit vorausgeschickte Aufregung in mich, wie eine zurückkehrende Flut, hält es aber in mir nicht aus und ohne Ziel reißt sie mich mit. Und doch kann ich diese Laune gar nicht benützen und kann nur nach Hause gehn, denn ich habe Gesicht und Hände schmutzig und verschwitzt, das Kleid fleckig und staubig, die Geschäftsmütze auf dem Kopfe und von Kistennägeln zerkratzte Stiefel. Ich gehe dann wie auf Wellen, klappere mit den Fingern beider Hände und mir entgegenkommenden Kindern fahre ich über das Haar.

Aber der Weg ist zu kurz. Gleich bin ich in meinem Hause, öffne die Lifttür und trete ein. Ich sehe, daß ich jetzt und plötzlich allein bin. Andere, die über Treppen steigen müssen, ermüden dabei ein wenig, müssen mit eilig atmenden Lungen warten, bis man die Tür der Wohnung öffnen kommt, haben dabei einen Grund für Ärger und Ungeduld, kommen jetzt ins Vorzimmer, wo sie den Hut aufhängen, und erst bis sie durch den Gang an einigen Glastüren vorbei in ihr eigenes Zimmer kommen, sind sie allein. Ich aber bin gleich allein im Lift, und schaue, auf die Knie gestützt, in den schmalen Spiegel. Als der Lift sich zu heben anfängt, sage ich: »Seid still, tretet zurück, wollt Ihr in den Schatten der Bäume, hinter die Draperien der Fenster, in das Laubengewölbe?« Ich rede mit den Zähnen und die Treppengeländer gleiten an den Milchglasscheiben hinunter wie stürzendes Wasser. »Flieget weg; Euere Flügel, die ich niemals gesehen habe, mögen Euch ins dörfliche Tal tragen oder nach Paris, wenn es Euch dorthin treibt.

Doch genießet die Aussicht des Fensters, wenn die Prozessionen aus allen drei Straßen kommen, einander nicht ausweichen, durcheinander gehn und zwischen ihren letzten Reihen den freien Platz wieder entstehen lassen. Winket mit den Tüchern, seid entsetzt, seid gerührt, lobet die schöne Dame, die vorüberfährt.

Geht über den Bach auf der hölzernen Brücke, nickt den badenden Kindern zu und staunet über das Hurra der tausend Matrosen auf dem fernen Panzerschiff.

Verfolget nur den unscheinbaren Mann und wenn Ihr ihn in einen Torweg gestoßen habt, beraubt ihn und seht ihm dann, jeder die Hände in den Taschen, nach, wie er traurig seines Weges in die linke Gasse geht. Die verstreut auf ihren Pferden galoppierende Polizei bändigt die Tiere und drängt Euch zurück. Lasset sie, die leeren Gassen werden sie unglücklich machen, ich weiß es. Schon reiten sie, ich bitte, paarweise weg, langsam um die Straßenecken, fliegend über die Plätze.«

Dann muß ich aussteigen, den Aufzug hinunterlassen, an der Türglocke läuten, und das Mädchen öffnet die Tür, während ich grüße.

.jpg)

Franz Kafka: Betrachtung 1913 – Für M.B.

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Franz Kafka, Kafka, Franz, Kafka, Franz

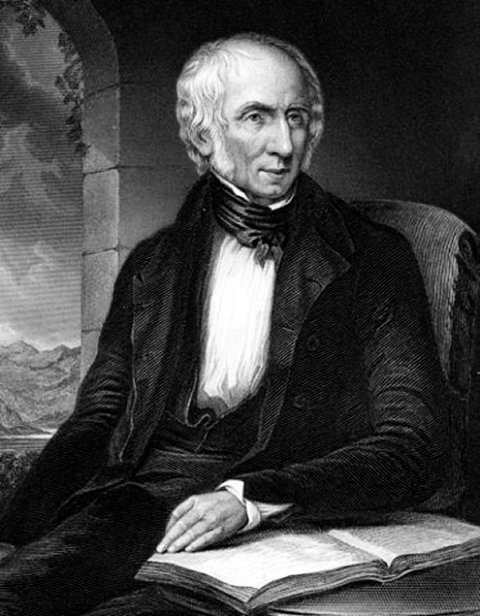

W i l l i a m W o r d s w o r t h

(1770-1850)

I travell’d among unknown Men

I travell’d among unknown Men,

In Lands beyond the Sea;

Nor England! did I know till then

What love I bore to thee.

‘Tis past, that melancholy dream!

Nor will I quit thy shore

A second time; for still I seem

To love thee more and more.

Among thy mountains did I feel

The joy of my desire;

And She I cherish’d turn’d her wheel

Beside an English fire.

Thy mornings shew’d–thy nights conceal’d

The bowers where Lucy play’d;

And thine is, too, the last green field

Which Lucy’s eyes survey’d!

.jpg)

William Wordsworth poetry

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Archive W-X, Wordsworth, William

J a n e A u s t e n

(1775 – 1817)

Ode to Pity

1

Ever musing I delight to tread

The Paths of honour and the Myrtle Grove

Whilst the pale Moon her beams doth shed

On disappointed Love.

While Philomel on airy hawthorn Bush

Sings sweet and Melancholy, And the thrush

Converses with the Dove.

2

Gently brawling down the turnpike road,

Sweetly noisy falls the Silent Stream–

The Moon emerges from behind a Cloud

And darts upon the Myrtle Grove her beam.

Ah! then what Lovely Scenes appear,

The hut, the Cot, the Grot, and Chapel queer,

And eke the Abbey too a mouldering heap,

Cnceal’d by aged pines her head doth rear

And quite invisible doth take a peep.

.jpg)

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Austen, Jane, Austen, Jane

William Wordsworth

(1770-1850)

T h e S e v e n S i s t e r s

or the Solitude of Binnorie

Seven Daughters had Lord Archibald,

All Children of one Mother:

I could not say in one short day

What love they bore each other,

A Garland of seven Lilies wrought!

Seven Sisters that together dwell;

But he, bold Knight as ever fought,

Their Father, took of them no thought,

He loved the Wars so well.

Sing, mournfully, oh! mournfully,

The Solitude of Binnorie!

Fresh blows the wind, a western wind,

And from the shores of Erin,

Across the wave, a Rover brave

To Binnorie is steering:

Right onward to the Scottish strand

The gallant ship is borne;

The Warriors leap upon the land,

And hark! the Leader of the Band

Hath blown his bugle horn.

Sing, mournfully, oh! mournfully,

The Solitude of Binnorie.

Beside a Grotto of their own,

With boughs above them closing,

The Seven are laid, and in the shade

They lie like Fawns reposing.

But now, upstarting with affright

At noise of Man and Steed,

Away they fly to left to right–

Of your fair household, Father Knight,

Methinks you take small heed!

Sing, mournfully, oh! mournfully,

The Solitude of Binnorie.

Away the seven fair Campbells fly,

And, over Hill and Hollow,

With menace proud, and insult loud,

The youthful Rovers follow.

Cried they, "Your Father loves to roam:

Enough for him to find

The empty House when he comes home;

For us your yellow ringlets comb,

For us be fair and kind!"

Sing, mournfully, oh! mournfully,

The Solitude of Binnorie.

Some close behind, some side by side,

Like clouds in stormy weather,

They run, and cry, "Nay let us die,

And let us die together."

A Lake was near; the shore was steep;

There never Foot had been;

They ran, and with a desperate leap

Together plung’d into the deep,

Nor ever more were seen.

Sing, mournfully, oh! mournfully,

The Solitude of Binnorie.

The Stream that flows out of the Lake,

As through the glen it rambles,

Repeats a moan o’er moss and stone,

For those seven lovely Campbells.

Seven little Islands, green and bare,

Have risen from out the deep:

The Fishers say, those Sisters fair

By Faeries are all buried there,

And there together sleep.

Sing, mournfully, oh! mournfully

The Solitude of Binnorie.

.jpg)

William Wordsworth poetry

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Wordsworth, William

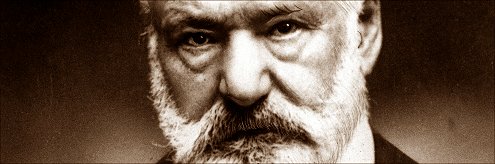

V i c t o r H u g o

(1802-1885)

Et Jeanne à Mariette a dit

Et Jeanne à Mariette a dit : – Je savais bien

Qu’en répondant : c’est moi, papa ne dirait rien.

Je n’ai pas peur de lui puisqu’il est mon grand-père.

Vois-tu, papa n’a pas le temps d’être en colère,

Il n’est jamais beaucoup fâché, parce qu’il faut

Qu’il regarde les fleurs, et quand il fait bien chaud

Il nous dit : N’allez pas au grand soleil nu-tête,

Et ne vous laissez pas piquer par une bête,

Courez, ne tirez pas le chien par son collier,

Prenez garde aux faux pas dans le grand escalier,

Et ne vous cognez pas contre les coins des marbres.

Jouez. Et puis après il s’en va dans les arbres.

.jpg)

Victor Hugo poésie

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive G-H, Archive G-H, Hugo, Victor, Victor Hugo

.jpg)

R o b e r t B r o w n i n g

(1812-1889)

O n e W o r d M o r e

I

There they are, my fifty men and women

Naming me the fifty poems finished!

Take them, Love, the book and me together:

Where the heart lies, let the brain lie also.

II

Rafael made a century of sonnets,

Made and wrote them in a certain volume

Dinted with the silver-pointed pencil

Else he only used to draw Madonnas:

These, the world might view–but one, the volume.

Who that one, you ask? Your heart instructs you.

Did she live and love it all her lifetime?

Did she drop, his lady of the sonnets,

Die, and let it drop beside her pillow

Where it lay in place of Rafael’s glory,

Rafael’s cheek so duteous and so loving–

Cheek, the world was wont to hail a painter’s,

Rafael’s cheek, her love had turned a poet’s?

III

You and I would rather read that volume

(Taken to his beating bosom by it),

Lean and list the bosom-beats of Rafael,

Would we not? than wonder at Madonnas–

Her, San Sisto names, and Her, Foligno,

Her, that visits Florence in a vision,

Her, that’s left with lilies in the Louvre–

Seen by us and all the world in circle.

IV

You and I will never read that volume.

Guido Reni, like his own eye’s apple

Guarded long the treasure-book and loved it.

Guido Reni dying, all Bologna

Cried, and the world cried too, "Ours, the treasure!"

Suddenly, as rare things will, it vanished.

V

Dante once prepared to paint an angel:

Whom to please? You whisper "Beatrice."

While he mused and traced it and retraced it

(Peradventure with a pen corroded

Still by drops of that hot ink he dipped for,

When, his left hand i’ the hair o’ the wicked,

Back he held the brow and pricked its stigma,

Bit into the live man’s flesh for parchment,

Loosed him, laughed to see the writing rankle,

Let the wretch go festering through Florence)–

Dante, who loved well because he hated,

Hated wickedness that hinders loving,

Dante standing, studying his angel–

In there broke the folk of his Inferno.

Says he–"Certain people of importance"

(Such he gave his daily, dreadful line to)

"Entered and would seize, forsooth, the poet."

Says the poet–"Then I stopped my painting."

VI

You and I would rather see that angel,

Painted by the tenderness of Dante–

Would we not?–than read a fresh Inferno.

VII

You and I will never see that picture.

While he mused on love and Beatrice,

While he softened o’er his outlined angel,

In they broke, those "people of importance":

We and Bice bear the loss forever.

VIII

What of Rafael’s sonnets, Dante’s picture?

This: no artist lives and loves, that longs not

Once, and only once, and for one only

(Ah, the prize!), to find his love a language

Fit and fair and simple and sufficient–

Using nature that’s an art to others,

Not, this one time, art that’s turned his nature.

Aye, of all the artists living, loving,

None but would forego his proper dowry–

Does he paint? He fain would write a poem–

Does he write? He fain would paint a picture,

Put to proof art alien to the artist’s,

Once, and only once, and for one only,

So to be the man and leave the artist,

Gain the man’s joy, miss the artist’s sorrow.

IX

Wherefore? Heaven’s gift takes earth’s abatement!

He who smites the rock and spreads the water,

Bidding drink and live a crowd beneath him,

Even he, the minute makes immortal,

Proves, perchance, but mortal in the minute,

Desecrates, belike, the deed in doing.

While he smites, how can he but remember,

So he smote before, in such a peril,

When they stood and mocked–"Shall smiting help us?"

When they drank and sneered–"A stroke is easy!"

When they wiped their mouths and went their journey,

Throwing him for thanks–"But drought was pleasant."

Thus old memories mar the actual triumph;

Thus the doing savors of disrelish;

Thus achievement lacks a gracious somewhat;

O’er-importuned brows becloud the mandate,

Carelessness or consciousness–the gesture.

For he bears an ancient wrong about him,

Sees and knows again those phalanxed faces,

Hears, yet one time more, the ‘customed prelude–

"How shouldst thou, of all men, smite, and save us?"

Guesses what is like to prove the sequel–

"Egypt’s flesh-pots–nay, the drought was better."

X

Oh, the crowd must have emphatic warrant

Theirs, the Sinai-forehead’s cloven brilliance,

Right-arm’s rod-sweep, tongue’s imperial fiat.

Never dares the man put off the prophet.

XI

Did he love one face from out the thousands

(Were she Jethro’s daughter, white and wifely,

Were she but the Ethiopian bondslave),

He would envy yon dumb patient camel,

Keeping a reserve of scanty water

Meant to save his own life in the desert;

Ready in the desert to deliver

(Kneeling down to let his breast be opened)

Hoard and life together for his mistress.

XII

I shall never, in the years remaining,

Paint you pictures, no, nor carve you statues,

Make you music that should all-express me;

So it seems: I stand on my attainment.

This of verse alone, one life allows me;

Verse and nothing else have I to give you.

Other heights in other lives, God willing:

All the gifts from all the heights, your own, Love!

XIII

Yet a semblance of resource avails us–

Shade so finely touched, love’s sense must seize it.

Take these lines, look lovingly and nearly,

Lines I write the first time and the last time.

He who works in fresco, steals a hair-brush,

Curbs the liberal hand, subservient proudly,

Cramps his spirit, crowds its all in little,

Makes a strange art of an art familiar,

Fills his lady’s missal-marge with flowerets.

He who blows through bronze may breathe through silver,

Fitly serenade a slumbrous princess.

He who writes may write for once as I do.

XIV

Love, you saw me gather men and women,

Live or dead or fashioned by my fancy,

Enter each and all, and use their service.

Speak from every mouth–the speech, a poem.

Hardly shall I tell my joys and sorrows,

Hopes and fears, belief and disbelieving:

I am mine and yours–the rest be all men’s,

Karshish, Cleon, Norbert, and the fifty.

Let me speak this once in my true person,

Not as Lippo, Roland, or Andrea,

Though the fruit of speech be just this sentence:

Pray you, look on these my men and women,

Take and keep my fifty poems finished;

Where my heart lies, let my brain lie also!

Poor the speech; be how I speak, for all things.

XV

Not but that you know me! Lo, the moon’s self!

Here in London, yonder late in Florence,

Still we find her face, the thrice-transfigured.

Curving on a sky imbrued with color,

Drifted over Fiesole by twilight,

Came she, our new crescent of a hair’s-breadth.

Full she flared it, lamping Samminiato,

Rounder ‘twixt the cypresses and rounder,

Perfect till the nightingales applauded.

Now, a piece of her old self, impoverished,

Hard to greet, she traverses the house-roofs,

Hurries with unhandsome thrift of silver,

Goes dispiritedly, glad to finish.

XVI

What, there’s nothing in the moon noteworthy?

Nay: for if that moon could love a mortal,

Use, to charm him (so to fit a fancy),

All her magic (’tis the old sweet mythos),

She would turn a new side to her mortal,

Side unseen of herdsman, huntsman, steersman–

Blank to Zoroaster on his terrace,

Blind to Galileo on his turret,

Dumb to Homer, dumb to Keats–him, even!

Think, the wonder of the moonstruck mortal–

When she turns round, comes again in heaven,

Opens out anew for worse or better!

Proves she like some portent of an iceberg

Swimming full upon the ship it founders,

Hungry with huge teeth of splintered crystals?

Proves she as the paved work of a sapphire

Seen by Moses when he climbed the mountain?

Moses, Aaron, Nadab, and Abihu

Climbed and saw the very God, the Highest,

Stand upon the paved work of a sapphire.

Like the bodied heaven in his clearness

Shone the stone, the sapphire of that paved work,

When they ate and drank and saw God also!

XVII

What were seen? None knows, none ever shall know.

Only this is sure–the sight were other,

Not the moon’s same side, born late in Florence,

Dying now impoverished here in London.

God be thanked, the meanest of his creatures

Boasts two soul-sides, one to face the world with,

One to show a woman when he loves her!

XVIII

This I say of me, but think of you, Love!

This to you–yourself my moon of poets!

Ah, but that’s the world’s side, there’s the wonder,

Thus they see you, praise you, think they know you!

There, in turn I stand with them and praise you–

Out of my own self, I dare to phrase it.

But the best is when I glide from out them,

Cross a step or two of dubious twilight,

Come out on the other side, the novel

Silent silver lights and darks undreamed of,

Where I hush and bless myself with silence.

XIX

Oh, their Rafael of the dear Madonnas,

Oh, their Dante of the dread Inferno,

Wrote one song–and in my brain I sing it,

Drew one angel–borne, see, on my bosom.

.jpg)

Robert Browning poetry

k e m p i s p o e t r y m a g a z i n e

More in: Browning, Robert

.jpg)

W i l l e m K l o o s

(1859-1938)

Laat mij nog éénmaal…

Laat mij nog éénmaal, in gedachten, kussen

Die warme lippen, door mijn kus ontbloeid;

Laat mij nog éénmaal aan die boezem sussen

Mijn arme hoofd, waarin de koorts-pijn gloeit.

Laat mij nog eens, klein kindje, rusten tussen

Die armen, waar mijn hart aan was geboeid,

In die zo lieve tijd, toen, zonder blussen,

’t Vereend gelaat door passie werd verschroeid.

Mijn lippen kussen wild, mijn oog staat droef –

Niet waar? gij lief! nu er geen lief meer wezen,

Geen arm zich om mijn hals bewegen zal:

Maar ik heb haast: mijn trekken worden stroef,

Als in de koû des doods, mijn armen vrezen

In beven, hangende op hun laatste val.

![]()

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Archive K-L, Kloos, Willem

.jpg)

Das Unglück des Junggesellen

Franz Kafka (1883-1924)

Es scheint so arg, Junggeselle zu bleiben, als alter Mann unter schwerer Wahrung der Würde um Aufnahme zu bitten, wenn man einen Abend mit Menschen verbringen will, krank zu sein und aus dem Winkel seines Bettes wochenlang das leere Zimmer anzusehn, immer vor dem Haustor Abschied zu nehmen, niemals neben seiner Frau sich die Treppe hinaufzudrängen, in seinem Zimmer nur Seitentüren zu haben, die in fremde Wohnungen führen, sein Nachtmahl in einer Hand nach Hause zu tragen, fremde Kinder anstaunen zu müssen und nicht immerfort wiederholen zu dürfen: »Ich habe keine«, sich im Aussehn und Benehmen nach ein oder zwei Junggesellen der Jugenderinnerungen auszubilden

So wird es sein, nur daß man auch in Wirklichkeit heute und später selbst dastehen wird, mit einem Körper und einem wirklichen Kopf, also auch einer Stirn, um mit der Hand an sie zu schlagen.

.jpg)

Franz Kafka: Betrachtung 1913, Für M.B.

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Franz Kafka, Kafka, Franz, Kafka, Franz

William Wordsworth

(1770-1850)

Rob Roy’s Grave

The History of Rob Roy is sufficiently known; his Grave is near the head of Loch Ketterine, in one of those small Pin-fold-like Burial-grounds, of neglected and desolate appearance, which the Traveller meets with in the Highlands of Scotland.

A famous Man is Robin Hood,

The English Ballad-singer’s joy!

And Scotland has a Thief as good,

An Outlaw of as daring mood,

She has her brave ROB ROY!

Then clear the weeds from off his Grave,

And let us chaunt a passing Stave

In honour of that Hero brave!

Heaven gave Rob Roy a dauntless heart,

And wondrous length and strength of arm:

Nor craved he more to quell his Foes,

Or keep his Friends from harm.

Yet was Rob Roy as wise as brave;

Forgive me if the phrase be strong;–

Poet worthy of Rob Roy

Must scorn a timid song.

Say, then, that he was wise as brave;

As wise in thought as bold in deed:

For in the principles of things

He sought his moral creed.

Said generous Rob, "What need of Books?

Burn all the Statutes and their shelves:

They stir us up against our Kind;

And worse, against Ourselves."

"We have a passion, make a law,

Too false to guide us or controul!

And for the law itself we fight

In bitterness of soul."

"And, puzzled, blinded thus, we lose

Distinctions that are plain and few:

These find I graven on my heart:

That tells me what to do."

"The Creatures see of flood and field,

And those that travel on the wind!

With them no strife can last; they live

In peace, and peace of mind."

"For why?–because the good old Rule

Sufficeth them, the simple Plan,

That they should take who have the power,

And they should keep who can."

"A lesson which is quickly learn’d,

A signal this which all can see!

Thus nothing here provokes the Strong

To wanton cruelty."

"All freakishness of mind is check’d;

He tam’d, who foolishly aspires;

While to the measure of his might

Each fashions his desires."

"All Kinds, and Creatures, stand and fall

By strength of prowess or of wit:

Tis God’s appointment who must sway,

And who is to submit."

"Since then," said Robin, "right is plain,

And longest life is but a day;

To have my ends, maintain my rights,

I’ll take the shortest way."

And thus among these rocks he liv’d,

Through summer’s heat and winter’s snow:

The Eagle, he was Lord above,

And Rob was Lord below.

So was it–would, at least, have been

But through untowardness of fate:

For Polity was then too strong;

He came an age too late,

Or shall we say an age too soon?

For, were the bold Man living now,

How might he flourish in his pride,

With buds on every bough!

Then rents and Factors, rights of chace,

Sheriffs, and Lairds and their domains

Would all have seem’d but paltry things,

Not worth a moment’s pains.

Rob Roy had never linger’d here,

To these few meagre Vales confin’d;

But thought how wide the world, the times

How fairly to his mind!

And to his Sword he would have said,

"Do Thou my sovereign will enact

From land to land through half the earth!

Judge thou of law and fact!"

"Tis fit that we should do our part;

Becoming, that mankind should learn

That we are not to be surpass’d

In fatherly concern."

"Of old things all are over old,

Of good things none are good enough:–

We’ll shew that we can help to frame

A world of other stuff."

"I, too, will have my Kings that take

From me the sign of life and death:

Kingdoms shall shift about, like clouds,

Obedient to my breath."

And, if the word had been fulfill’d,

As might have been, then, thought of joy!

France would have had her present Boast;

And we our brave Rob Roy!

Oh! say not so; compare them not;

I would not wrong thee, Champion brave!

Would wrong thee no where; least of all

Here standing by thy Grave.

For Thou, although with some wild thoughts,

Wild Chieftain of a Savage Clan!

Hadst this to boast of; thou didst love

The liberty of Man.

And, had it been thy lot to live

With us who now behold the light,

Thou would’st have nobly stirr’d thyself,

And battled for the Right.

For Robin was the poor Man’s stay

The poor man’s heart, the poor man’s hand;

And all the oppress’d, who wanted strength,

Had Robin’s to command.

Bear witness many a pensive sigh

Of thoughtful Herdsman when he strays

Alone upon Loch Veol’s Heights,

And by Loch Lomond’s Braes!

And, far and near, through vale and hill,

Are faces that attest the same;

And kindle, like a fire new stirr’d,

At sound of ROB ROY’s name.

.jpg)

William Wordsworth poetry

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Wordsworth, William

F r i e d r i c h v o n S c h i l l e r

(1759-1805)

A n G o e t h e

(als er den Mahoment von Voltaire auf die Bühne brachte)

Du selbst, der uns von falschem Regelzwange

Zur Wahrheit und Natur zurückgeführt,

Der, in der Wiege schon ein Held, die Schlange

Erstickt, die unsern Genius umschnürt,

Du, den die Kunst, die göttliche, schon lange

Mit ihrer reinen Priesterbinde ziert,

Du opferst auf zertrümmerten Altären

Der Aftermuse, die wir nicht mehr ehren?

Einheim’scher Kunst ist dieser Schauplatz eigen,

Hier wird nicht fremden Götzen mehr gedient;

Wir können mutig einen Lorbeer zeigen,

Der auf dem deutschen Pindus selbst gegrünt.

Selbst in der Künste Heiligtum zu steigen,

Hat sich der deutsche Genius erkühnt,

Und auf der Spur des Griechen und des Britten

Ist er dem bessern Ruhme nachgeschritten.

Denn dort, wo Sklaven knien, Despoten walten,

Wo sich die eitle Aftergröße bläht,

Da kann die Kunst das Edle nicht gestalten,

Von keinem Ludwig wird es ausgesät;

Aus eigner Fülle muss es sich entfalten,

Es borget nicht von ird’scher Majestät,

Nur mit der Wahrheit wird er sich vermählen,

Und seine Glut durchflammt nur freie Seelen.

Drum nicht, in alte Fesseln uns zu schlagen,

Erneuerst du dies Spiel der alten Zeit,

Nicht, uns zurückzuführen zu den Tagen

Charakterloser Minderjährigkeit.

Es wär’ ein eitel und vergeblich Wagen

Zu fallen ins bewegte Rad der Zeit;

Geflügelt fort entführen es die Stunden;

Das Neue kommt, das Alte ist verschwunden.

Erweitert jetzt ist des Theaters Enge,

In seinem Raume drängt sich eine Welt;

Nicht mehr der Worte rednerisch Gepränge,

Nur der Natur getreues Bild gefällt;

Verbannet ist der Sitten falsche Strenge,

Und menschlich handelt, menschlich fühlt der Held.

Die Leidenschaft erhebt die freien Töne,

Und in der Wahrheit findet man das Schöne.

Doch leicht gezimmert nur ist Thespis Wagen,

Und er ist gleich dem acheront’schen Kahn;

Nur Schatten und Idole kann er tragen,

Und drängt das rohe Leben sich heran,

So droht das leichte Fahrzeug umzuschlagen,

Das nur die flücht’gen Geister fassen kann.

Der Schein soll nie die Wirklichkeit erreichen,

Und siegt Natur, so muss die Kunst entweichen.

Denn auf dem bretternen Gerüst der Szene

Wird eine Idealwelt aufgetan.

Nichts sei hier wahr und wirklich, als die Träne,

Die Rührung ruht auf keinem Sinnenwahn.

Aufrichtig ist die wahre Melpomene,

Sie kündigt nichts als eine Fabel an,

Und weiß durch tiefe Wahrheit zu entzücken;

Die falsche stellt sich wahr, um zu berücken.

Es droht die Kunst vom Schauplatz zu verschwinden,

Ihr wildes Reich behauptet Phantasie;

Die Bühne will sie wie die Welt entzünden,

Das Niedrigste und Höchste menget sie.

Nur bei dem Franken war noch Kunst zu finden,

Erschwang er gleich ihr hohes Urbild nie:

Gebannt in unveränderlichen Schranken

Hält er sie fest, und nimmer darf sie wanken.

Ein heiliger Bezirk ist ihm die Szene;

Verbannt aus ihrem festlichen Gebiet

Sind der Natur nachlässig rohe Töne,

Die Sprache selbst erhebt sich ihm zum Lied:

Es ist ein Reich des Wohllauts und der Schöne.

In edler Ordnung greifet Glied in Glied,

Zum ernsten Tempel füget sich das Ganze,

Und die Bewegung borget Reiz vom Tanze,

Nicht Muster zwar darf uns der Franke werden,

Aus seiner Kunst spricht kein lebend’ger Geist;

Des falschen Anstands prunkende Gebärden

Verschmäht der Sinn, der nur das Wahre preist!

Ein Führer nur zum Bessern soll er werden,

Er komme, wie ein abgeschiedner Geist,

Zu reinigen die oft entweihte Szene

Zum würd’gen Sitz der alten Melpomene.

Friedrich von Schiller Gedichte

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Schiller, Friedrich von

.jpg)

G e r a r d M a n l e y H o p k i n s

(1844-1889)

H e n r y P u r c e l l

The poet wishes well to the divine genius of Purcell and praises him that, whereas other musicians have given utterance to the moods of man’s mind, he has, beyond that, uttered in notes the very make and species of man as created both in him and in all men generally.

Have, fair fallen, O fair, fair have fallen, so dear

To me, so arch-especial a spirit as heaves in Henry Purcell,

An age is now since passed, since parted; with the reversal

Of the outward sentence low lays him, listed to a heresy, here.

Not mood in him nor meaning, proud fire or sacred fear,

Or love or pity or all that sweet notes not his might nursle:

It is the forgèd feature finds me; it is the rehearsal

Of own, of abrupt self there so thrusts on, so throngs the ear.

Let him Oh! with his air of angels then lift me, lay me! only I’ll

Have an eye to the sakes of him, quaint moonmarks, to his pelted plumage under

Wings: so some great stormfowl, whenever he has walked his while

The thunder-purple seabeach plumèd purple-of-thunder,

If a wuthering of his palmy snow-pinions scatter a colossal smile

Off him, but meaning motion fans fresh our wits with wonder.

![]()

Gerard Manley Hopkins poetry

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Hopkins, Gerard Manley

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature