Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

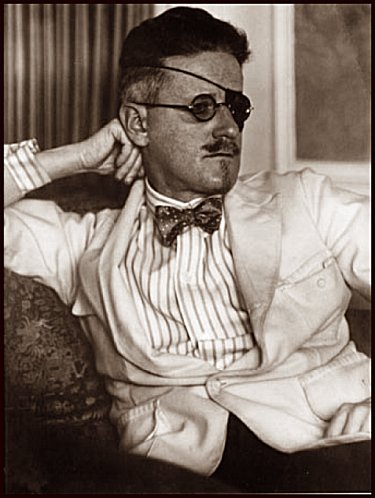

James Joyce

(1882-1941)

After The Race

The cars came scudding in towards Dublin, running evenly like pellets in the groove of the Naas Road. At the crest of the hill at Inchicore sightseers had gathered in clumps to watch the cars careering homeward and through this channel of poverty and inaction the Continent sped its wealth and industry. Now and again the clumps of people raised the cheer of the gratefully oppressed. Their sympathy, however, was for the blue cars, the cars of their friends, the French.

The French, moreover, were virtual victors. Their team had finished solidly; they had been placed second and third and the driver of the winning German car was reported a Belgian. Each blue car, therefore, received a double measure of welcome as it topped the crest of the hill and each cheer of welcome was acknowledged with smiles and nods by those in the car. In one of these trimly built cars was a party of four young men whose spirits seemed to be at present well above the level of successful Gallicism: in fact, these four young men were almost hilarious. They were Charles Segouin, the owner of the car; Andre Riviere, a young electrician of Canadian birth; a huge Hungarian named Villona and a neatly groomed young man named Doyle. Segouin was in good humour because he had unexpectedly received some orders in advance (he was about to start a motor establishment in Paris) and Riviere was in good humour because he was to be appointed manager of the establishment; these two young men (who were cousins) were also in good humour because of the success of the French cars. Villona was in good humour because he had had a very satisfactory luncheon; and besides he was an optimist by nature. The fourth member of the party, however, was too excited to be genuinely happy.

He was about twenty-six years of age, with a soft, light brown moustache and rather innocent-looking grey eyes. His father, who had begun life as an advanced Nationalist, had modified his views early. He had made his money as a butcher in Kingstown and by opening shops in Dublin and in the suburbs he had made his money many times over. He had also been fortunate enough to secure some of the police contracts and in the end he had become rich enough to be alluded to in the Dublin newspapers as a merchant prince. He had sent his son to England to be educated in a big Catholic college and had afterwards sent him to Dublin University to study law. Jimmy did not study very earnestly and took to bad courses for a while. He had money and he was popular; and he divided his time curiously between musical and motoring circles. Then he had been sent for a term to Cambridge to see a little life. His father, remonstrative, but covertly proud of the excess, had paid his bills and brought him home. It was at Cambridge that he had met Segouin. They were not much more than acquaintances as yet but Jimmy found great pleasure in the society of one who had seen so much of the world and was reputed to own some of the biggest hotels in France. Such a person (as his father agreed) was well worth knowing, even if he had not been the charming companion he was. Villona was entertaining also, a brilliant pianist, but, unfortunately, very poor.

The car ran on merrily with its cargo of hilarious youth. The two cousins sat on the front seat; Jimmy and his Hungarian friend sat behind. Decidedly Villona was in excellent spirits; he kept up a deep bass hum of melody for miles of the road The Frenchmen flung their laughter and light words over their shoulders and often Jimmy had to strain forward to catch the quick phrase. This was not altogether pleasant for him, as he had nearly always to make a deft guess at the meaning and shout back a suitable answer in the face of a high wind. Besides Villona’s humming would confuse anybody; the noise of the car, too.

Rapid motion through space elates one; so does notoriety; so does the possession of money. These were three good reasons for Jimmy’s excitement. He had been seen by many of his friends that day in the company of these Continentals. At the control Segouin had presented him to one of the French competitors and, in answer to his confused murmur of compliment, the swarthy face of the driver had disclosed a line of shining white teeth. It was pleasant after that honour to return to the profane world of spectators amid nudges and significant looks. Then as to money, he really had a great sum under his control. Segouin, perhaps, would not think it a great sum but Jimmy who, in spite of temporary errors, was at heart the inheritor of solid instincts knew well with what difficulty it had been got together. This knowledge had previously kept his bills within the limits of reasonable recklessness, and if he had been so conscious of the labour latent in money when there had been question merely of some freak of the higher intelligence, how much more so now when he was about to stake the greater part of his substance! It was a serious thing for him.

Of course, the investment was a good one and Segouin had managed to give the impression that it was by a favour of friendship the mite of Irish money was to be included in the capital of the concern. Jimmy had a respect for his father’s shrewdness in business matters and in this case it had been his father who had first suggested the investment; money to be made in the motor business, pots of money. Moreover Segouin had the unmistakable air of wealth. Jimmy set out to translate into days’ work that lordly car in which he sat. How smoothly it ran. In what style they had come careering along the country roads! The journey laid a magical finger on the genuine pulse of life and gallantly the machinery of human nerves strove to answer the bounding courses of the swift blue animal.

They drove down Dame Street. The street was busy with unusual traffic, loud with the horns of motorists and the gongs of impatient tram-drivers. Near the Bank Segouin drew up and Jimmy and his friend alighted. A little knot of people collected on the footpath to pay homage to the snorting motor. The party was to dine together that evening in Segouin’s hotel and, meanwhile, Jimmy and his friend, who was staying with him, were to go home to dress. The car steered out slowly for Grafton Street while the two young men pushed their way through the knot of gazers. They walked northward with a curious feeling of disappointment in the exercise, while the city hung its pale globes of light above them in a haze of summer evening.

In Jimmy’s house this dinner had been pronounced an occasion. A certain pride mingled with his parents’ trepidation, a certain eagerness, also, to play fast and loose for the names of great foreign cities have at least this virtue. Jimmy, too, looked very well when he was dressed and, as he stood in the hall giving a last equation to the bows of his dress tie, his father may have felt even commercially satisfied at having secured for his son qualities often unpurchaseable. His father, therefore, was unusually friendly with Villona and his manner expressed a real respect for foreign accomplishments; but this subtlety of his host was probably lost upon the Hungarian, who was beginning to have a sharp desire for his dinner.

The dinner was excellent, exquisite. Segouin, Jimmy decided, had a very refined taste. The party was increased by a young Englishman named Routh whom Jimmy had seen with Segouin at Cambridge. The young men supped in a snug room lit by electric candle lamps. They talked volubly and with little reserve. Jimmy, whose imagination was kindling, conceived the lively youth of the Frenchmen twined elegantly upon the firm framework of the Englishman’s manner. A graceful image of his, he thought, and a just one. He admired the dexterity with which their host directed the conversation. The five young men had various tastes and their tongues had been loosened. Villona, with immense respect, began to discover to the mildly surprised Englishman the beauties of the English madrigal, deploring the loss of old instruments. Riviere, not wholly ingenuously, undertook to explain to Jimmy the triumph of the French mechanicians. The resonant voice of the Hungarian was about to prevail in ridicule of the spurious lutes of the romantic painters when Segouin shepherded his party into politics. Here was congenial ground for all. Jimmy, under generous influences, felt the buried zeal of his father wake to life within him: he aroused the torpid Routh at last. The room grew doubly hot and Segouin’s task grew harder each moment: there was even danger of personal spite. The alert host at an opportunity lifted his glass to Humanity and, when the toast had been drunk, he threw open a window significantly.

That night the city wore the mask of a capital. The five young men strolled along Stephen’s Green in a faint cloud of aromatic smoke. They talked loudly and gaily and their cloaks dangled from their shoulders. The people made way for them. At the corner of Grafton Street a short fat man was putting two handsome ladies on a car in charge of another fat man. The car drove off and the short fat man caught sight of the party.

“Andre.”

“It’s Farley!”

A torrent of talk followed. Farley was an American. No one knew very well what the talk was about. Villona and Riviere were the noisiest, but all the men were excited. They got up on a car, squeezing themselves together amid much laughter. They drove by the crowd, blended now into soft colours, to a music of merry bells. They took the train at Westland Row and in a few seconds, as it seemed to Jimmy, they were walking out of Kingstown Station. The ticket-collector saluted Jimmy; he was an old man:

“Fine night, sir!”

It was a serene summer night; the harbour lay like a darkened mirror at their feet. They proceeded towards it with linked arms, singing Cadet Roussel in chorus, stamping their feet at every:

“Ho! Ho! Hohe, vraiment!”

They got into a rowboat at the slip and made out for the American’s yacht. There was to be supper, music, cards. Villona said with conviction:

“It is delightful!”

There was a yacht piano in the cabin. Villona played a waltz for Farley and Riviere, Farley acting as cavalier and Riviere as lady. Then an impromptu square dance, the men devising original figures. What merriment! Jimmy took his part with a will; this was seeing life, at least. Then Farley got out of breath and cried “Stop!” A man brought in a light supper, and the young men sat down to it for form’s sake. They drank, however: it was Bohemian. They drank Ireland, England, France, Hungary, the United States of America. Jimmy made a speech, a long speech, Villona saying: “Hear! hear!” whenever there was a pause. There was a great clapping of hands when he sat down. It must have been a good speech. Farley clapped him on the back and laughed loudly. What jovial fellows! What good company they were!

Cards! cards! The table was cleared. Villona returned quietly to his piano and played voluntaries for them. The other men played game after game, flinging themselves boldly into the adventure. They drank the health of the Queen of Hearts and of the Queen of Diamonds. Jimmy felt obscurely the lack of an audience: the wit was flashing. Play ran very high and paper began to pass. Jimmy did not know exactly who was winning but he knew that he was losing. But it was his own fault for he frequently mistook his cards and the other men had to calculate his I.O.U.’s for him. They were devils of fellows but he wished they would stop: it was getting late. Someone gave the toast of the yacht The Belle of Newport and then someone proposed one great game for a finish.

The piano had stopped; Villona must have gone up on deck. It was a terrible game. They stopped just before the end of it to drink for luck. Jimmy understood that the game lay between Routh and Segouin. What excitement! Jimmy was excited too; he would lose, of course. How much had he written away? The men rose to their feet to play the last tricks. talking and gesticulating. Routh won. The cabin shook with the young men’s cheering and the cards were bundled together. They began then to gather in what they had won. Farley and Jimmy were the heaviest losers.

He knew that he would regret in the morning but at present he was glad of the rest, glad of the dark stupor that would cover up his folly. He leaned his elbows on the table and rested his head between his hands, counting the beats of his temples. The cabin door opened and he saw the Hungarian standing in a shaft of grey light:

“Daybreak, gentlemen!”

James Joyce: After the race

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive I-J, Joyce, James, Joyce, James

William Shakespeare

(1564-1616)

THE SONNETS

112

Your love and pity doth th’ impression fill,

Which vulgar scandal stamped upon my brow,

For what care I who calls me well or ill,

So you o’er-green my bad, my good allow?

You are my all the world, and I must strive,

To know my shames and praises from your tongue,

None else to me, nor I to none alive,

That my steeled sense or changes right or wrong.

In so profound abysm I throw all care

Of others’ voices, that my adder’s sense,

To critic and to flatterer stopped are:

Mark how with my neglect I do dispense.

You are so strongly in my purpose bred,

That all the world besides methinks are dead.

![]()

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: -Shakespeare Sonnets

Clemens Brentano

(1778-1842)

Die Abendwinde wehen . . .

Die Abendwinde wehen,

Ich muß zur Linde gehen,

Muß einsam weinend stehen,

Es kommt kein Sternenschein;

Die kleinen Vöglein sehen

Betrübt zu mir und flehen,

Und wenn sie schlafen gehen,

Dann wein ich ganz allein!

»Ich hör ein Sichlein rauschen,

Wohl rauschen durch den Klee,

Ich hör ein Mägdlein klagen

Von Weh, von bitterm Weh!«

Ich soll ein Lied dir singen,

Ich muß die Hände ringen,

Das Herz will mir zerspringen

In bittrer Tränenflut,

Ich sing und möchte weinen,

So lang der Mond mag scheinen,

Sehn ich mich nach der Einen,

Bei der mein Leiden ruht!

»Ich hör ein Sichlein rauschen etc.«

Mein Herz muß nun vollenden,

Da sich die Zeit will wenden,

Es fällt mir aus den Händen

Der letzte Lebenstraum.

Entsetzliches Verschwenden

In allen Elementen,

Mußt ich den Geist verpfänden,

Und alles war nur Schaum!

»Ich hör ein Sichlein rauschen etc.«

Was du mir hast gegeben,

Genügt ein ganzes Leben

Zum Himmel zu erheben;

O sage, ich sei dein!

Da kehrt sie sich mit Schweigen

Und gibt kein Lebenszeichen,

Da mußte ich erbleichen,

Mein Herz ward wie ein Stein.

»Ich hör ein Sichlein rauschen etc.«

Heb Frühling jetzt die Schwingen,

Laß kleine Vöglein singen,

Laß Blümlein aufwärts dringen,

Süß Lieb geht durch den Hain.

Ich mußt mein Herz bezwingen,

Muß alles niederringen,

Darf nichts zu Tage bringen,

Wir waren nicht allein!

»Ich hör ein Sichlein rauschen etc.«

Wenn du von deiner Schwelle

Mit deinen Augen helle,

Wie letzte Lebenswelle

Zum Strom der Nacht mich treibst,

Da weiß ich, daß sie Schmerzen

Gebären meinem Herzen

Und löschen alle Kerzen,

Daß du mir leuchtend bleibst!

»Ich hör ein Sichlein rauschen,

Wohl rauschen durch den Klee,

Ich hör ein Mägdlein klagen

Von Weh, von bitterm Weh!«

Hans Hermans foto’s – Natuurdagboek 10-11

Gedicht Clemens Brentano

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Hans Hermans Photos

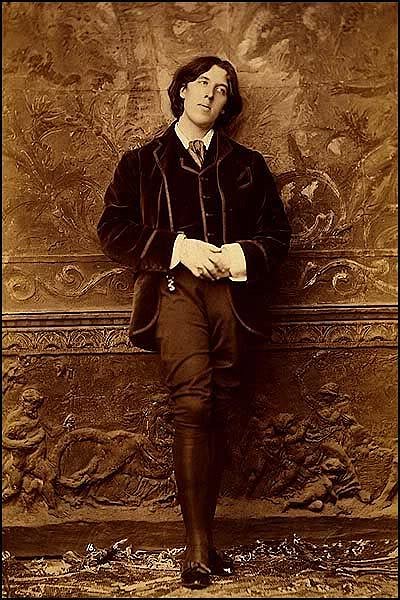

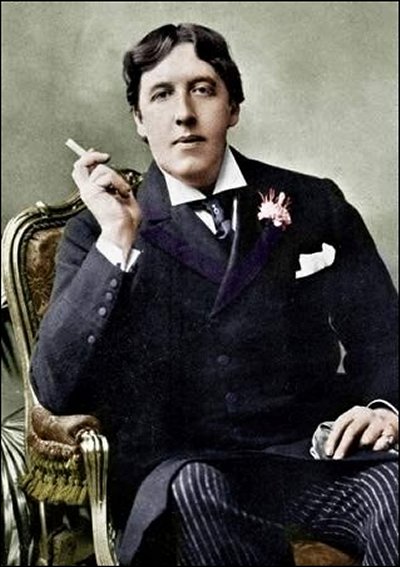

Oscar Wilde

(1854-1900)

The Grave of Keats

(sonnet)

Rid of the world’s injustice, and his pain,

He rests at last beneath God’s veil of blue:

Taken from life when life and love were new

The youngest of the martyrs here is lain,

Fair as Sebastian, and as early slain.

No cypress shades his grave, no funeral yew,

But gentle violets weeping with the dew

Weave on his bones an ever-blossoming chain.

O proudest heart that broke for misery!

O sweetest lips since those of Mitylene!

O poet-painter of our English land!

Thy name was writ in water – it shall stand:

And tears like mine will keep thy memory green,

As Isabella did her Basil tree.

Rome

Oscar Wilde

Het graf van Keats

(sonnet)

In de nieuwe vertaling van Cornelis W. Schoneveld

Van ‘s werelds onrecht en zijn pijn bevrijd,

Rust hij op ‘t laatst onder God’s hemelbaan:

Uit liefde en leven, nieuw nog, heengegaan

Ligt hier de jongste lijder neergevlijd,

Schoon als Sebastiaan, even jong ook dood.

Hier geeft cipres noch taxus schaduw af,

Maar waar viooltjes wenen op zijn graf

Is zijn gebeente nooit van bloei ontbloot.

O hart vol trots dat brak door hoe het leed!

O stem die ‘t zoetst sinds Mytylene’s is!

O schilder-dichter van ons Engeland!

Je schreef je naam in water-hij houdt stand:

En ook mijn traan steunt jouw gedachtenis,

Zoals Isabella’s balsemkruid dat deed.

Rome

VALLEND BLOEMBLAD

Verzameling van 90 korte gedichten van OSCAR WILDE

Vertaald door Cornelis W. Schoneveld

tweetalige uitgave, 2011

ongepubliceerd

fleursdumal.nl nagazine

More in: John Keats, Keats, John, Wilde, Wilde, Oscar

Renée Crevel

(1900-1935)

Tu as le remord

Tu as le remords d’avoir tué ton père sans avoir même acquis cent années de souvenirs.

Toujours les neurasthénies comme des fleurs en mie de pain.

Si tu essayais du tric-trac.

Sautent les dés.

Homme ou femme?

Chien ou chat?

Mais il y aura le chien qui sera tout de même un chat,

encore la vieille chanson des départs qui restent

et puis ce fauteuil de bois.

Les poitrines n’ont plus qu’un sein tout en haut des corps sans sexes;

Ton enfance fut aux curés en jupes de femmes;

dans la crypte du Sacré-Coeur tu n’as pas su faire l’amour.

Un oiseau dans ton cerveau.

Cet oiseau sans voix,

cet oiseau qui n’a pas volé,

cet oiseau qui n’a pas chanté,

apte au seul frisson de l’inutilité.

Comme des frères il aimait,

les bateaux petits;

bateaux colibris,

leur essaim posé

n’a rien enseigné.

Rouille, sang de carcasses

figé dans la mort,

et puis toujours et puis encor

alentour une eau si lasse

avec le plomb des ménagères

trop souvent mères.

Tu as froid mais ne sait ni mourir ni pleurer.

Triste entre les quais méchants

que tout homme ici-bas méprise,

tu vas, fleuve des villes grises

et sans espoir d’océan

Renée Crevel poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive C-D, Crevel, Renée

William Shakespeare

Sonnet 111

O for my sake do you with Fortune chide,

The guilty goddess of my harmful deeds,

That did not better for my life provide,

Than public means which public manners breeds.

Thence comes it that my name receives a brand,

And almost thence my nature is subdued

To what it works in, like the dyer’s hand:

Pity me then, and wish I were renewed,

Whilst like a willing patient I will drink,

Potions of eisel ‘gainst my strong infection,

No bitterness that I will bitter think,

Nor double penance to correct correction.

Pity me then dear friend, and I assure ye,

Even that your pity is enough to cure me.

William Shakespeare

Sonnet 111

O, straf jij eens voor mij Fortuna af,

Godin die mij met kwade daden nekt,

En mij aan leven niet veel beters gaf

Dan wat volks geld aan volks gedrag verwekt.

Zo kwam dat brandmerk op mijn naam tot stand,

En dompelde zich bijna heel mijn aard

Daarin waarmee zij werkt, als ‘n ververshand;

Heb meelij dus, en acht iets nieuws mij waard,

En, als ‘n patiënt zo meegaand, drink ik dan:

Azijndrank helpt mij van besmetting af,

Geen bitterheid waar ik niet tegen kan,

Geen dubbele straffen schuw ik voor mijn straf.

Heb meelij dus, mijn vriend, en volg mijn lezing,

Dat meelij al volstaat voor mijn genezing.

(Vertaling: Cornelis W. Schoneveld, januari 2012)

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: -Shakespeare Sonnets, Shakespeare

Joseph von Eichendorff

(1788—1857)

Waldgespräch

Es ist schon spät, es wird schon kalt,

Was reitst du einsam durch den Wald?

Der Wald ist lang, du bist allein,

Du schöne Braut! Ich führ dich heim!

»Groß ist der Männer Trug und List,

Vor Schmerz mein Herz gebrochen ist,

Wohl irrt das Waldhorn her und hin,

O flieh! Du weißt nicht, wer ich bin.«

»Du kennst mich wohl – von hohem Stein

Schaut still mein Schloß tief in den Rhein.

Es ist schon spät, es wird schon kalt,

Kommst nimmermehr aus diesem Wald!«

Hans Hermans photos – Natuurdagboek 9-11

Gedicht Joseph von Eichendorff

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive E-F, Hans Hermans Photos, MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY - department of ravens & crows, birds of prey, riding a zebra, spring, summer, autumn, winter

Verwisseling van de hoofden

De grotere, mooie zussen van mijn kamergenoot

waren echte teenagers, hielden van Buddy Holly.

Ik was tien jaar, verbleef zes hoog in het ziekenhuis,

leed aan een long waarin zich water had opgehoopt.

Uit een raam op de gang zag ik de zeven koolmijnen

in mijn provincie. Ik kende hun plaatsnamen en kon

de terril aanwijzen waarover elke dag mijn vader liep.

Herfst, de roetmoppen waren al uit de schoorsteen geveegd,

een vrachtauto laadde kolen af op ons erf

– de mijnwerkers mochten per dag een volle emmer

naar huis dragen, kolenbons sparen. Nadat ik kolen

in kruiwagens had geschopt telde ik mijn handblaren.

Kompel was hij niet, zijn naamwoord lichtte ik uit

compulsieve rompzinnen. Hij werkte in ’t zonlicht

boven op de mijn, schop ter hand, is in veertig jaar

niet één keer in de schacht afgedaald. Op de terril

won hij op een regendag vertrouwen van een jonge,

verdwaalde hond, bracht hem in zijn tas op de bus mee naar huis.

Er zijn jonge hondjes van gekomen.

Het ijverig bespuugde eelt in zijn handen is verdwenen.

Op zijn schouders staat soms mijn hoofd, dat bevangen raakt

door enge gedachten aan de reusachtige dreiging

van zware aardlagen op de diepdonkere, hete delfplek,

waar een claustrofobie, het eeuwig uitschurend stof en

nesten van ratten de totale schedelholte willen innemen.

Of op mijn schouders zijn hoofd, waarin ik eenvoudig denk

de dood te kunnen afhouden die hem onder de grond stopt.

Richard Steegmans

(Uit: Richard Steegmans: Ringelorend zelfportret op haar leeuwenhuid, uitgeverij Holland, Haarlem, 2005)

Richard Steegmans (Hasselt, 1952) is dichter en muzikant met een grote voorliefde voor rock, pop, soul, blues, country uit de jaren 60. Hij publiceerde de dichtbundels Uitgeslagen zomers, uitgeverij Perdu, Amsterdam, 2002, en Ringelorend zelfportret op haar leeuwenhuid, uitgeverij Holland, Haarlem, 2005. Gedichten van zijn hand verschenen in de literaire tijdschriften De Gids, Poëziekrant, Parmentier, DWB, Deus ex Machina, De Brakke Hond, Tortuca, Krakatau, Tzum en in talrijke bloemlezingen.

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Steegmans, Richard

William Shakespeare

(1564-1616)

THE SONNETS

111

O for my sake do you with Fortune chide,

The guilty goddess of my harmful deeds,

That did not better for my life provide,

Than public means which public manners breeds.

Thence comes it that my name receives a brand,

And almost thence my nature is subdued

To what it works in, like the dyer’s hand:

Pity me then, and wish I were renewed,

Whilst like a willing patient I will drink,

Potions of eisel ‘gainst my strong infection,

No bitterness that I will bitter think,

Nor double penance to correct correction.

Pity me then dear friend, and I assure ye,

Even that your pity is enough to cure me.

![]()

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: -Shakespeare Sonnets

Oscar Wilde

(1854-1900)

Impression du Voyage

(sonnet)

The sea was sapphire colored, and the sky

Burned like a heated opal through the air,

We hoisted sail; the wind was blowing fair

For the blue lands that to the eastward lie.

From the steep prow I marked with quickening eye

Zakynthos, every olive grove and creek,

Ithaca’s cliff, Lycaon’s snowy peak,

And all the flower-strewn hills of Arcady.

The flapping of the sail against the mast,

The ripple of the water on the side,

The ripple of girls’ laughter at the stern,

The only sounds:- when ‘gan the West to burn,

And a red sun upon the seas to ride,

I stood upon the soil of Greece at last!

Katakolo

Oscar Wilde

Reisimpressie

(sonnet)

In de nieuwe vertaling van Cornelis W. Schoneveld

Het zeevlak glom met een saffieren tint,

De hemel stond als hete opaal in brand,

De wind trok aan; we tuigden ‘t want,

Voor ‘t blauwe land dat oostwaarts zich bevindt.

Ik zag vanaf de hoogste stevenkant

Zakynthos’ kreek en zijn olijventrots,

Lycaon’s sneeuwtop en Ithaca’s rots,

En ‘t bloemenrijk Arcadisch heuvelland.

De fok die klapperend om de stag zich wond,

Het water kabbelend voorlangs de boeg,

De meisjes kwebbelend in de kajuit,

Meer klonk er niet – dan brandde langzaam uit

Een rode zon op zee, die ‘m westwaarts droeg,

Ik stond nu eindelijk op Griekse grond!

Katakolo

VALLEND BLOEMBLAD

Verzameling van 90 korte gedichten van OSCAR WILDE

Vertaald door Cornelis W. Schoneveld

tweetalige uitgave, 2011

ongepubliceerd

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Wilde, Wilde, Oscar

Dromen voor beginners

Een: Doe een handgeschreven brief op de post.

Twee: Plooi u in een warm bed naar een diepe slaap.

Drie: Heb in uw bestemming het volste vertrouwen.

Vier: Wals alleen met lang vergeten klasgenootjes.

Vijf: Groet zwaaiende matrozen met een glimlach.

Zes: Streel de drieste, warme zadels zachtjes.

Zeven: Hoor van de haan die u spant de klik.

Bert Bevers

(Verschenen in Het Hemelbed, Diksmuide, augustus 2006)

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Bevers, Bert

Niet te bevatten

Duizend jaar worden

alleen al de gedachte

is te lang voor haiku.

Freda Kamphuis haiku

kempis.nl poetry magazine

©2011 fk

More in: Archive K-L, Kamphuis, Freda

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature