Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

Ton van Reen

spitsuur

Een sirene jankt

en de dag

spat open

fabrieken lopen leeg

schoorstenen wuiven

de arbeiders na

auto’s spelen van

wie komt er in mijn hokje

langzaam lopend

in een rijtje

behangen ze de lucht

met hun ratelend hart

op hoge benen

lopen meisjes voorbij

ongemerkt halen ze

tussen zwoele wanden van ogen

de avond binnen

Uit: Ton van Reen, Blijvend vers, Verzamelde gedichten (1965-2007). Uitgeverij De Contrabas, 2011, ISBN 9789079432462, 144 pagina’s, paperback

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive Q-R, Reen, Ton van

![]()

31 januari 2012

Schrijfster Doeschka Meijsing overleden

In haar woonplaats Amsterdam is gisteravond de schrijfster Doeschka Meijsing overleden. Zij werd vierenzestig jaar. Meijsing stierf aan de complicaties van een zware operatie.

Doeschka Meijsing schreef vele verhalen, gedichten, essays en romans. Ze debuteerde in 1974 bij Querido met De hanen en andere verhalen. Voor Tijger, tijger! (1980) ontving ze de Multatuliprijs. De tweede man (2000) werd genomineerd voor de AKO Literatuurprijs en betekende Meijsings doorbraak naar het grote publiek. Haar roman 100% chemie (2002) werd genomineerd voor de Libris Literatuur Prijs en kan worden gezien als een opmaat tot Moord, haar deel van de roman Moord & Doodslag (2005), die ze samen met haar broer Geerten Meijsing schreef. In 2008 publiceerde ze de roman Over de liefde, die bekroond werd met de F. Bordewijkprijs, de Opzij Literatuurprijs en de AKO Literatuurprijs. Dit aangrijpende relaas over de schaamte die liefde heet, werd haar laatste boek.

Annette Portegies, directeur/uitgever Querido: ‘Doeschka Meijsing verborg een diepe kwetsbaarheid achter een superieure vorm van ironie, zowel in haar werk als in haar leven. Weerspannig als ze was, was ze een vrouw om van te houden. Querido rouwt om de dood van Doeschka, die bijna veertig jaar aan de uitgeverij verbonden was. De Nederlandse literatuur verliest opnieuw een auteur van wereldformaat.’

De begrafenis zal in besloten kring plaatsvinden.

Daarachter

De diepte ja,

die kennen we.

Die is vaak nogal hartgrondig.

Maar de geur van violieren.

De deur naar de andere

kamer.

Waar ieder

voorwerp specifiek de geliefde

spiegelt.

Waar ieder

ander een rivaal is.

Die deur.

Daarachter.

Wie er liederen zingt.

Die.

(uit: ‘Paard Heer Mantel’, 1986)

Doeschka Meijsing (1947-2012) schreef verhalen, gedichten, essays en romans. Ze debuteerde in 1974 met De hanen en andere verhalen. Voor Tijger, tijger! (1980) ontving ze de Multatuliprijs. De tweede man (2000) werd genomineerd voor de AKO Literatuurprijs en betekende Meijsings doorbraak naar het grote publiek. Haar roman 100% chemie (2002) werd genomineerd voor de Libris Literatuur Prijs en kan worden gezien als een opmaat naar Moord, haar deel van de spraakmakende roman Moord & Doodslag (2005), die ze samen met haar broer Geerten schreef. In 2007 publiceerde ze de kleine roman De eerste jaren en in 2008 volgde haar veelgeprezen bestseller Over de liefde die bekroond werd met de die bekroond werd met de F. Bordewijkprijs, de Opzij Literatuurprijs en de AKO Literatuurprijs. Doeschka Meijsing heeft een indrukwekkend oeuvre op haar naam staan, dat in 1997 werd bekroond met de Annie Romeinprijs.

romans en verhalen:

De hanen en andere verhalen (1974)

Robinson (1976)

De kat achterna (1977)

Tijger, tijger! (1980)

Utopia of De geschiedenissen van Thomas (1982)

Beer en Jager (1987)

De beproeving (1990)

Vuur en zijde (1992)

Beste vriend (1994)

De weg naar Caviano (1996)

De tweede man (2000)

100 % chemie (2002)

Moord & Doodslag (2005) met Geerten Meijsing

De eerste jaren (2007)

Over de liefde (2008)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive M-N, In Memoriam

joep eijkens (links) en bert bevers

Kreunende tijd

nieuwe gedichtencyclus Bert Bevers

met foto’s van Joep Eijkens

IV

Toen je hier ter aarde werd besteld met die

gedoofde blik naar de ontelbare sterren van het

noorden gericht sneeuwde het. Toen wel. Om te

sterven volstond het om met ademen te stoppen.

Dat wel. Maar dat allengs muller zwijgen van alle

geliefden valt heel wat zwaarder. O hemel toch,

een heel leven lang vergat je dit te schrijven.

VIII

Verloochen verleden nooit. Het is er voor altijd. Het gaat

gewoon niet weg. Het zingt lang na. Zinder maar. Doe maar.

Keer maar rustig eeuwig weer, aarzelende treurengel en

maak alles maar mooier dan het is. Ik zie mensen rondlopen

met een donker gemoed, met de koele zekerheid van een profeet.

Of ze aan galgen zijn gehangen slaan achter hen schaduwen

neder. In de verte blaft een hond een brandweerwagen na.

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Bevers, Bert, Joep Eijkens Photos

Poëzie in de kroeg in Assen

op zondag 5 februari

Zondag 5 februari 2012 is het weer zo ver. Van 15.30 tot 17.30 uur zijn de inwoners van heel Drenthe en omstreken van harte welkom om aan te schuiven in een van de gelegenheden om te genieten van een drankje maar vooral van een verse portie gedichten.

Gezien de vele positieve reacties van het afgelopen jaar, kon een tweede editie van Poëzie in de Kroeg niet uitblijven. In samenwerking met de gemeente Assen hebben stadsdichter Mischa van Huijstee en Geert Loman weer een aantal dichters weten te strikken om er voor de bezoekers een aangename middag van te maken. De poëten zullen in groepjes langs een aantal kroegen in de binnenstad trekken. Als u blijft zitten in één van de kroegen hoort u ze allemaal voorbij komen.

Dichters die hebben toegezegd een bijdrage te leveren zijn: Geert Loman, Delia Bremer, Ria Westerhuis, John van Beek, Nicolette Leenstra, Bert de Jonge, De Dames Samen, Rik Holwerda, Paul Borggreve, Freda Kamphuis en Johan Hovinga.

U kunt hun poëzie beluisteren in de café’s Tastoe, Whispers, Cosy Corner en de Witte Bal.

De organisatie is erg blij dat de Witte Bal ook zijn deuren opent, aangezien de eigenaar Tieme van Veen nog maar net overleden is. Hij was er als een van de eersten bij om zijn medewerking toe te zeggen aan dit evenement.

De toegang is gratis. Na afloop komen de dichters nog even bij elkaar in café Whispers. Dan is er alle gelegenheid om nog even na te praten en/of een drankje te drinken.

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: City Poets / Stadsdichters, Kamphuis, Freda

Over het doorstaan van de rijpheid

kan ik allerhande vruchten uit vreemde landen

ongeschonden in een mand op je hoofd laden

erop toezien dat ze geen connotaties aangaan

met een tot woordeloos geslagen lichaamsdeel

tegenwerpen dat op je buik opgediend worden

ze uit de bluts houdt, ze op het stilleven drukt

ze in voorhoedegevechten brengt tegen de tong

die van elke schaal de vlezigste bodem afzoekt

in de wetenschap dat een eetbare banaan zaadjes

ontbeert, van haar kweker het snoeimes trotseert

of zal ik met Burlatkersen je paternosteren

Richard Steegmans

(Uit: Richard Steegmans: Ringelorend zelfportret op haar leeuwenhuid, uitgeverij Holland, Haarlem, 2005)

Richard Steegmans gedichten

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Steegmans, Richard

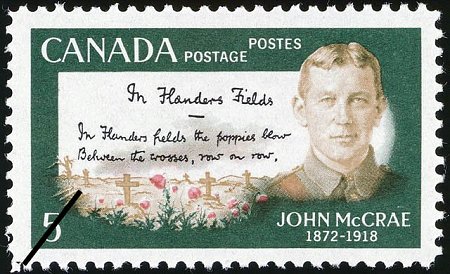

John McCrae

(1872 – 1918)

Then And Now

Beneath her window in the fragrant night

I half forget how truant years have flown

Since I looked up to see her chamber-light,

Or catch, perchance, her slender shadow thrown

Upon the casement; but the nodding leaves

Sweep lazily across the unlit pane,

And to and fro beneath the shadowy eaves,

Like restless birds, the breath of coming rain

Creeps, lilac-laden, up the village street

When all is still, as if the very trees

Were listening for the coming of her feet

That come no more; yet, lest I weep, the breeze

Sings some forgotten song of those old years

Until my heart grows far too glad for tears.

John McCrae poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive C-D, McCrae, John

Freda Kamphuis

Flatscape (2011)

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Freda Kamphuis, Kamphuis, Freda

William Shakespeare

(1564-1616)

THE SONNETS

113

Since I left you, mine eye is in my mind,

And that which governs me to go about,

Doth part his function, and is partly blind,

Seems seeing, but effectually is out:

For it no form delivers to the heart

Of bird, of flower, or shape which it doth latch,

Of his quick objects hath the mind no part,

Nor his own vision holds what it doth catch:

For if it see the rud’st or gentlest sight,

The most sweet favour or deformed’st creature,

The mountain, or the sea, the day, or night:

The crow, or dove, it shapes them to your feature.

Incapable of more, replete with you,

My most true mind thus maketh mine untrue.

![]()

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: -Shakespeare Sonnets

Blues met bekentenis

Eens beroept de geliefde zich op een ommekeer van gevoelens,

loopt ze op een onzichtbare morgen voorgoed zonder koffers zijn idioom uit.

Hij neemt voor kort de kleur aan

van een overgewaaid bevattelijk lied,

zeult het knaagdier als in de voering

van winterjassen mee in bluesmuziek.

Verlamde neger, doordrenkte schoenenen een grof pak, vlooit zijn stem na

in ritmes waarop zijn mannelijkheid is

vertrapt. Een man van herhaalde malen.

Blues is uitgelicht een botsing

van klank op dichtgeslagen deuren.

Blues is achteropgeraakte

liefde, een uitgeleefde die overgaat in schoongewreven instrumenten, waarmee

voor nieuwe liefde weer geen mond kan gesnoerd.

Straten, met de lome lengte nu van veel nog te vergeten dagen,

waren hun zij aan zij zo gewend van

blues is geen onderdak bekend.

Richard Steegmans

(Uit: Richard Steegmans: Ringelorend zelfportret op haar leeuwenhuid, uitgeverij Holland, Haarlem, 2005)

Richard Steegmans gedichten

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Steegmans, Richard

Ivo van Leeuwen, 2011

Portret van Esther Porcelijn, actrice en stadsdichter van Tilburg

©ivovanleeuwen

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Ivo van Leeuwen, Porcelijn, Esther, Porcelijn, Esther

Weggeblazen

Opgesloten in je ogen

Helemaal alleen

Weggeblazen, opgetild

Bliksemschicht door mij heen

Pleun Andriessen

Pleun Andriessen (11) is de nieuwe Kinderstadsdichter van Tilburg. Pleun schreef speciaal voor Gedichtendag, 26 januari 2012, een nieuw gedicht. Het past mooi binnen het thema van deze dag, ‘Stroom’: ‘Stroom is ritme, flow, een vloeiende en ongrijpbare beweging van A naar B, dankzij een teveel aan de ene of een tekort aan de andere kant. Stromen kunnen uit woorden bestaan, uit lading, gedachten, uit informatie, stoffen of dingen. Stromen verbinden plekken op deze wereld en brengen mensen bij elkaar. Of juist niet. ‘Stroom’ is er altijd en overal.’

Meer informatie:

≡Website Kinderstadsdichter Tilburg

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Andriessen, Pleun, Archive A-B

Heinrich Heine

(1797-1856)

Seekrankheit

Die grauen Nachmittagswolken

Senken sich tiefer hinab auf das Meer,

Das ihnen dunkel entgegensteigt,

Und zwischendurch jagt das Schiff.

Seekrank sitz ich noch immer am Mastbaum,

Und mache Betrachtungen über mich selber,

Uralte, aschgraue Betrachtungen,

Die schon der Vater Loth gemacht,

Als er des Guten zuviel genossen

Und sich nachher so übel befand.

Mitunter denk ich auch alter Geschichtchen:

Wie kreuzbezeichnete Pilger der Vorzeit,

Auf stürmischer Meerfahrt, das trostreiche Bildnis

Der heiligen Jungfrau gläubig küßten;

Wie kranke Ritter, in solcher Seenot,

Den lieben Handschuh ihrer Dame

An die Lippen preßten, gleich getröstet –

Ich aber sitze und kaue verdrießlich

Einen alten Hering, den salzigen Tröster

In Katzenjammer und Hundetrübsal!

Vergebens späht mein Auge und sucht

Die deutsche Küste. Doch ach! nur Wasser,

Und abermals Wasser, bewegtes Wasser!

Wie der Winterwandrer des Abends sich sehnt

Nach einer warmen, innigen Tasse Tee,

So sehnt sich jetzt mein Herz nach dir,

Mein deutsches Vaterland!

Mag immerhin dein süßer Boden bedeckt sein

Mit Wahnsinn, Husaren, schlechten Versen

Und laulich dünnen Traktätchen;

Mögen immerhin deine Zebras

Mit Rosen sich mästen statt Disteln;

Mögen immerhin deine noblen Affen

In müßigem Putz sich vornehm spreizen

Und sich besser dünken als all das andre

Banausisch dahinwandelnde Hornvieh;

Mag immerhin deine Schneckenversammlung

Sich für unsterblich halten,

Weil sie so langsam dahinkriecht,

Und mag sie täglich Stimmen sammeln,

Ob den Maden des Käses der Käse gehört?

Und noch lange Zeit in Beratung ziehen,

Wie man die ägyptischen Schafe veredle,

Damit ihre Wolle sich beßre

Und der Hirt sie scheren könne wie andre,

Ohn Unterschied –

Immerhin, mag Torheit und Unrecht

Dich ganz bedecken, o Deutschland!

Ich sehne mich dennoch nach dir:

Denn wenigstens bist du noch festes Land.

Hans Hermans photos – Natuurdagboek 11-11

Gedicht Heinrich Heine

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive G-H, Hans Hermans Photos, Heine, Heinrich

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature