Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Or see the index

IJzerhard

Stalen glans op paars blad. Op hoge stelen wiegt

de ijzerhard. Middaguur in onze hortus botanicus

liegt niet: het land van gisteren is toe. Alles bloeit.

Ik hoor kinderen op een nabijgelegen schoolplein

driewerf hoera roepen. Er wordt traag gesproeid

door een man die graag bezorgd lijkt. Soms wil hij

de tuin uit hollen en het op een gillen zetten, maar

zijn bladeren houden niet van geluid. Het ruikt naar

zoethout. Een koolwitje laveert tegen wind in, en zand

wijkt zachtjes voor zaad. Wolkjes zijn licht en de goden

nabij. Laat alle mensen maar weten waar de verhalen

over gaan. Wie een grens trekt heeft een huis.

Bert Bevers

verschenen in Eigen terrein – Gedichten 1998-2013, Uitgeverij WEL, Bergen op Zoom, 2013

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Bevers, Bert

Friedrich Hebbel

(1813-1863)

Knabentod

Vom Berg, der Knab’,

Der zieht hinab

In heißen Sommertagen;

Im Tannenwald,

Da macht er Halt,

Er kann sich kaum noch tragen.

Den wilden Bach,

Er sieht ihn jach

In’s Thal herunter schäumen;

Ihn dürstet sehr,

Nun noch viel mehr:

Nur hin! Wer würde säumen!

Da ist die Flut!

O, in der Glut,

Was kann so köstlich blinken!

Er schöpft und trinkt,

Er stürzt und sinkt

Und trinkt noch im Versinken!

Das Lied ist aus,

Und macht’s dir Graus:

Wer wird’s im Winter singen!

Zur Sommerzeit

Bist du bereit,

Dem Knaben nachzuspringen.

Friedrich Hebbel poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive G-H, CLASSIC POETRY

The Sorrows of Young Werther (15)

by J.W. von Goethe

JULY 1.

The consolation Charlotte can bring to an invalid I experience from my own heart, which suffers more from her absence than many a poor creature lingering on a bed of sickness. She is gone to spend a few days in the town with a very worthy woman, who is given over by the physicians, and wishes to have Charlotte near her in her last moments. I accompanied her last week on a visit to the Vicar of S–, a small village in the mountains, about a league hence. We arrived about four o’clock: Charlotte had taken her little sister with her. When we entered the vicarage court, we found the good old man sitting on a bench before the door, under the shade of two large walnut-trees. At the sight of Charlotte he seemed to gain new life, rose, forgot his stick, and ventured to walk toward her. She ran to him, and made him sit down again; then, placing herself by his side, she gave him a number of messages from her father, and then caught up his youngest child, a dirty, ugly little thing, the joy of his old age, and kissed it. I wish you could have witnessed her attention to this old man,–how she raised her voice on account of his deafness; how she told him of healthy young people, who had been carried off when it was least expected; praised the virtues of Carlsbad, and commended his determination to spend the ensuing summer there; and assured him that he looked better and stronger than he did when she saw him last. I, in the meantime, paid attention to his good lady. The old man seemed quite in spirits; and as I could not help admiring the beauty of the walnut-trees, which formed such an agreeable shade over our heads, he began, though with some little difficulty, to tell us their history. “As to the oldest,” said he, “we do not know who planted it,–some say one clergyman, and some another: but the younger one, there behind us, is exactly the age of my wife, fifty years old next October; her father planted it in the morning, and in the evening she came into the world. My wife’s father was my predecessor here, and I cannot tell you how fond he was of that tree; and it is fully as dear to me. Under the shade of that very tree, upon a log of wood, my wife was seated knitting, when I, a poor student, came into this court for the first time, just seven and twenty years ago.”

Charlotte inquired for his daughter. He said she was gone with Herr Schmidt to the meadows, and was with the haymakers. The old man then resumed his story, and told us how his predecessor had taken a fancy to him, as had his daughter likewise; and how he had become first his curate, and subsequently his successor. He had scarcely finished his story when his daughter returned through the garden, accompanied by the above-mentioned Herr Schmidt. She welcomed Charlotte affectionately, and I confess I was much taken with her appearance. She was a lively-looking, good-humoured brunette, quite competent to amuse one for a short time in the country. Her lover (for such Herr Schmidt evidently appeared to be) was a polite, reserved personage, and would not join our conversation, notwithstanding all Charlotte’s endeavours to draw him out. I was much annoyed at observing, by his countenance, that his silence did not arise from want of talent, but from caprice and ill-humour. This subsequently became very evident, when we set out to take a walk, and Frederica joining Charlotte, with whom I was talking, the worthy gentleman’s face, which was naturally rather sombre, became so dark and angry that Charlotte was obliged to touch my arm, and remind me that I was talking too much to Frederica. Nothing distresses me more than to see men torment each other; particularly when in the flower of their age, in the very season of pleasure, they waste their few short days of sunshine in quarrels and disputes, and only perceive their error when it is too late to repair it. This thought dwelt upon my mind; and in the evening, when we returned to the vicar’s, and were sitting round the table with our bread end milk, the conversation turned on the joys and sorrows of the world, I could not resist the temptation to inveigh bitterly against ill-humour. “We are apt,” said I, “to complain, but–with very little cause, that our happy days are few, and our evil days many. If our hearts were always disposed to receive the benefits Heaven sends us, we should acquire strength to support evil when it comes.” “But,” observed the vicar’s wife, “we cannot always command our tempers, so much depends upon the constitution: when the body suffers, the mind is ill at ease.” “I acknowledge that,” I continued; “but we must consider such a disposition in the light of a disease, and inquire whether there is no remedy for it.”

“I should be glad to hear one,” said Charlotte: “at least, I think very much depends upon ourselves; I know it is so with me. When anything annoys me, and disturbs my temper, I hasten into the garden, hum a couple of country dances, and it is all right with me directly.” “That is what I meant,” I replied; “ill-humour resembles indolence: it is natural to us; but if once we have courage to exert ourselves, we find our work run fresh from our hands, and we experience in the activity from which we shrank a real enjoyment.” Frederica listened very attentively: and the young man objected, that we were not masters of ourselves, and still less so of our feelings. “The question is about a disagreeable feeling,” I added, “from which every one would willingly escape, but none know their own power without trial. Invalids are glad to consult physicians, and submit to the most scrupulous regimen, the most nauseous medicines, in order to recover their health.” I observed that the good old man inclined his head, and exerted himself to hear our discourse; so I raised my voice, and addressed myself directly to him. “We preach against a great many crimes,” I observed, “but I never remember a sermon delivered against ill-humour.” “That may do very well for your town clergymen,” said he: “country people are never ill-humoured; though, indeed, it might be useful, occasionally, to my wife for instance, and the judge.” We all laughed, as did he likewise very cordially, till he fell into a fit of coughing, which interrupted our conversation for a time. Herr Schmidt resumed the subject. “You call ill humour a crime,” he remarked, “but I think you use too strong a term.” “Not at all,” I replied, “if that deserves the name which is so pernicious to ourselves and our neighbours. Is it not enough that we want the power to make one another happy, must we deprive each other of the pleasure which we can all make for ourselves? Show me the man who has the courage to hide his ill-humour, who bears the whole burden himself, without disturbing the peace of those around him. No: ill-humour arises from an inward consciousness of our own want of merit, from a discontent which ever accompanies that envy which foolish vanity engenders. We see people happy, whom we have not made so, and cannot endure the sight.” Charlotte looked at me with a smile; she observed the emotion with which I spoke: and a tear in the eyes of Frederica stimulated me to proceed. “Woe unto those,” I said, “who use their power over a human heart to destroy the simple pleasures it would naturally enjoy! All the favours, all the attentions, in the world cannot compensate for the loss of that happiness which a cruel tyranny has destroyed.” My heart was full as I spoke. A recollection of many things which had happened pressed upon my mind, and filled my eyes with tears.

“We should daily repeat to ourselves,” I exclaimed, “that we should not interfere with our friends, unless to leave them in possession of their own joys, and increase their happiness by sharing it with them! But when their souls are tormented by a violent passion, or their hearts rent with grief, is it in your power to afford them the slightest consolation?

“And when the last fatal malady seizes the being whose untimely grave you have prepared, when she lies languid and exhausted before you, her dim eyes raised to heaven, and the damp of death upon her pallid brow, there you stand at her bedside like a condemned criminal, with the bitter feeling that your whole fortune could not save her; and the agonising thought wrings you, that all your efforts are powerless to impart even a moment’s strength to the departing soul, or quicken her with a transitory consolation.”

At these words the remembrance of a similar scene at which I had been once present fell with full force upon my heart. I buried my face in my handkerchief, and hastened from the room, and was only recalled to my recollection by Charlotte’s voice, who reminded me that it was time to return home. With what tenderness she chid me on the way for the too eager interest I took in everything! She declared it would do me injury, and that I ought to spare myself. Yes, my angel! I will do so for your sake.

The Sorrows of Young Werther (Die Leiden des jungen Werther) by J.W. von Goethe. Translated by R.D. Boylan.

To be continued

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: -Die Leiden des jungen Werther, Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von

Rob Stuart: Entropy

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: *Concrete + Visual Poetry P-T, Rob Stuart, Rob Stuart, Stuart, Rob

Théophile Gautier

(1811-1872)

A deux beaux yeux

Vous avez un regard singulier et charmant ;

Comme la lune au fond du lac qui la reflète,

Votre prunelle, où brille une humide paillette,

Au coin de vos doux yeux roule languissamment ;

Ils semblent avoir pris ses feux au diamant ;

Ils sont de plus belle eau qu’une perle parfaite,

Et vos grands cils émus, de leur aile inquiète,

Ne voilent qu’à demi leur vif rayonnement.

Mille petits amours, à leur miroir de flamme,

Se viennent regarder et s’y trouvent plus beaux,

Et les désirs y vont rallumer leurs flambeaux.

Ils sont si transparents, qu’ils laissent voir votre âme,

Comme une fleur céleste au calice idéal

Que l’on apercevrait à travers un cristal.

Théophile Gautier poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive G-H, Gautier, Théophile

Passer domesticus

Zijn schroomvol hopen op een kleine holte

onder schuine dakpannen vergt steeds meer

tijd. Hij hunkert naar nabijheid van toonloos

dorre struiken, naar van kreupelhout de lege

grijste. Het vaakst zie ik hem nog in de Zoo.

Daar kronkelt in hoekjes hout dat hij graag

heeft, wordt hij door papegaaien bij het eten

in hun kooien als een kleine broer aanvaard.

Slapen zie ik hem nooit. Om het stoere snaveltje

glanst constant een vogeltjesglimlach. Hij hupt

en roetsjt met graagte in de buurt. Hij wil meer.

Hij wil u wel nabij zijn maar toch niet al te zeer.

Bert Bevers

eerder verschenen in Eigen terrein – Gedichten 1998-2013, Uitgeverij WEL, Bergen op Zoom, 2013

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Bevers, Bert, MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY - department of ravens & crows, birds of prey, riding a zebra, spring, summer, autumn, winter

The Sorrows of Young Werther (14)

by J.W. von Goethe

JUNE 29.

The day before yesterday, the physician came from the town to pay a visit to the judge. He found me on the floor playing with Charlotte’s children. Some of them were scrambling over me, and others romped with me; and, as I caught and tickled them, they made a great noise. The doctor is a formal sort of personage: he adjusts the plaits of his ruffles, and continually settles his frill whilst he is talking to you; and he thought my conduct beneath the dignity of a sensible man. I could perceive this by his countenance. But I did not suffer myself to be disturbed. I allowed him to continue his wise conversation, whilst I rebuilt the children’s card houses for them as fast as they threw them down. He went about the town afterward, complaining that the judge’s children were spoiled enough before, but that now Werther was completely ruining them.

Yes, my dear Wilhelm, nothing on this earth affects my heart so much as children. When I look on at their doings; when I mark in the little creatures the seeds of all those virtues and qualities which they will one day find so indispensable; when I behold in the obstinate all the future firmness and constancy of a noble character; in the capricious, that levity and gaiety of temper which will carry them lightly over the dangers and troubles of life, their whole nature simple and unpolluted,–then I call to mind the golden words of the Great Teacher of mankind, “Unless ye become like one of these!” And now, my friend, these children, who are our equals, whom we ought to consider as our models, we treat them as though they were our subjects. They are allowed no will of their own. And have we, then, none ourselves? Whence comes our exclusive right? Is it because we are older and more experienced?

Great God! from the height of thy heaven thou beholdest great children and little children, and no others; and thy Son has long since declared which afford thee greatest pleasure. But they believe in him, and hear him not,–that, too, is an old story; and they train their children after their own image, etc.

Adieu, Wilhelm: I will not further bewilder myself with this subject.

The Sorrows of Young Werther (Die Leiden des jungen Werther) by J.W. von Goethe. Translated by R.D. Boylan.

To be continued

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: -Die Leiden des jungen Werther, Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von

Freda Kamphuis:

woordverduistering – collage – 2014

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: *Concrete + Visual Poetry K-O, Freda Kamphuis, Kamphuis, Freda

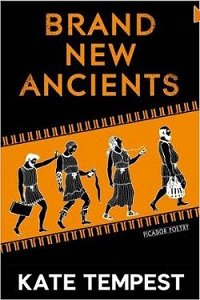

Kate Tempest started out when she was 16, rapping at strangers on night busses and pestering mc’s to let her on the mic at raves. Ten years later she is a published playwright, poet and respected recording artist.

Her theatre writing includes Wasted for Paines Plough, Brand New Ancients for the BAC, and Glasshouse for Cardboard Citizens.

She has written poetry for the Royal Shakespeare Company, Barnado’s, Channel 4 and the BBC. She has worked with Amnesty International to create a schools pack helping secondary school children write their own protest songs, and was invited to write and perform a new poem for Aung San Suu Kyi when she recieved the Ambassador of Conscience award in Dublin.

Kate released her debut album Balance with Sound of Rum in 2011. She has featured on songs with Sinead O Connor, Bastille, the King Blues, Damien Dempsey, Pink Punk, and Landslide. She has just finished recording a new solo album Everybody Down with acclaimed music producer Dan Carey. She’s toured extensively, supporting Billy Bragg on his UK tour, as well as supporting Scroobius Pip, Femi Kuti, Saul Williams and John Cooper Clarke. She is 2 x slam winner at the prestigious Nu-Yorican poetry cafe in New York. She’s played all the major UK and European music festivals either solo or with Sound of Rum. She’s headlined Latitude festival and her poetry has been featured on the BBC’s Glastonbury highlights. In 2012 she launched her first poetry book to a sell out crowd at the Old Vic theatre in London.

She’s led workshops in schools, colleges and youth groups across the UK and taught a creative writing class at Yale. She’s given lectures at Goldsmiths University and to newly qualified English teachers for the Prince’s Teaching Institute.

Her first spoken word release Broken Herd came out on Pure Groove in 2009. Her poetry book/CD/DVD package Everything Speaks in its Own Way was published on her own imprint Zingaro in 2012, and is available now from this site: # website kate tempest

A new collection of poetry will be out in 2014, published by Picador.

Kate Tempest: Brand New Ancients On Film – Part 1

In association with the Brand New Ancients tour, Battersea Arts Centre in collaboration with director Joe Roberts, has produced three short films interpreting Kate’s spoken word through moving image.

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Art & Literature News, AUDIO, CINEMA, RADIO & TV, Kate/Kae Tempest, Poetry Slam, Tempest, Kate/Kae

The Sorrows of Young Werther (13)

by J.W. von Goethe

JUNE 21.

My days are as happy as those reserved by God for his elect; and, whatever be my fate hereafter, I can never say that I have not tasted joy,–the purest joy of life. You know Walheim. I am now completely settled there. In that spot I am only half a league from Charlotte; and there I enjoy myself, and taste all the pleasure which can fall to the lot of man.

Little did I imagine, when I selected Walheim for my pedestrian excursions, that all heaven lay so near it. How often in my wanderings from the hillside or from the meadows across the river, have I beheld this hunting-lodge, which now contains within it all the joy of my heart!

I have often, my dear Wilhelm, reflected on the eagerness men feel to wander and make new discoveries, and upon that secret impulse which afterward inclines them to return to their narrow circle, conform to the laws of custom, and embarrass themselves no longer with what passes around them.

It is so strange how, when I came here first, and gazed upon that lovely valley from the hillside, I felt charmed with the entire scene surrounding me. The little wood opposite–how delightful to sit under its shade! How fine the view from that point of rock! Then, that delightful chain of hills, and the exquisite valleys at their feet!

Could I but wander and lose myself amongst them! I went, and returned without finding what I wished. Distance, my friend, is like futurity. A dim vastness is spread before our souls: the perceptions of our mind are as obscure as those of our vision; and we desire earnestly to surrender up our whole being, that it may be filled with the complete and perfect bliss of one glorious emotion. But alas! when we have attained our object, when the distant there becomes the present here, all is changed: we are as poor and circumscribed as ever, and our souls still languish for unattainable happiness.

So does the restless traveller pant for his native soil, and find in his own cottage, in the arms of his wife, in the affections of his children, and in the labour necessary for their support, that happiness which he had sought in vain through the wide world.

When, in the morning at sunrise, I go out to Walheim, and with my own hands gather in the garden the pease which are to serve for my dinner, when I sit down to shell them, and read my Homer during the intervals, and then, selecting a saucepan from the kitchen, fetch my own butter, put my mess on the fire, cover it up, and sit down to stir it as occasion requires, I figure to myself the illustrious suitors of Penelope, killing, dressing, and preparing their own oxen and swine.

Nothing fills me with a more pure and genuine sense of happiness than those traits of patriarchal life which, thank Heaven! I can imitate without affectation. Happy is it, indeed, for me that my heart is capable of feeling the same simple and innocent pleasure as the peasant whose table is covered with food of his own rearing, and who not only enjoys his meal, but remembers with delight the happy days and sunny mornings when he planted it, the soft evenings when he watered it, and the pleasure he experienced in watching its daily growth.

The Sorrows of Young Werther (Die Leiden des jungen Werther) by J.W. von Goethe. Translated by R.D. Boylan.

To be continued

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: -Die Leiden des jungen Werther, Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von

Gabriele D’Annunzio

(1863-1938)

La Pioggia nel Pineto

Taci. Su le soglie

del bosco non odo

parole che dici

umane ; ma odo

parole più nuove

che parlano gocciole e foglie

lontane.

Ascolta. Piove

dalle nuvole sparse.

Piove su le tamerici

salmastre ed arse,

piove su i pini

scagliosi ed irti,

piove su i mirti

divini,

su le ginestre fulgenti

di fiori accolti,

su i ginepri folti

di coccole aulenti,

piove su i nostri vólti

silvani,

piove su le nostre mani

ignude,

su i nostri vetimenti

leggieri,

su i freschi pensieri

che l’anima schiude

novella,

su la favola bella

che ieri

t’illuse, che oggi m’illude,

o Ermione.

Odi ? La pioggia cade

su la solitaria

verdura

con un crepitìo che dura

e varia nell’ aria

secondo le fronde

più rade, men rade.

Ascolta. Risponde

al pianto il canto

delle cicale

che il pianto australe

non impaura,

né il ciel cinerino.

E il pino

ha un suono, e il mirto

altro suono, e il ginepro

altro ancóra, stromenti

diversi

sotto innumerevoli dita.

E immersi

noi siam nello spirto

silvestre,

d’arborea vita viventi ;

e il tuo vólto ebro

è molle di pioggia

come una foglia,

e le tue chiome

auliscono come

le chiare ginestre,

o creatura terrestre

che hai nome

Ermione.

Ascolta, ascolta. L’accordo

delle aeree cicale

a poco a poco

più sordo

si fa sotto il pianto

che cresce ;

ma un canto vi si mesce

più roco

che di laggiù sale,

dall’ umida ombra remota.

Più sordo e più fioco

s’allenta, si spegne.

Sola una nota

ancor trema, si spegne,

risorge, trema, si spegne.

Non s’ode voce del mare.

Or s’ode su tutta la fronda

crosciare

l’argentea pioggia

che monda,

il croscio che varia

secondo la fronda

più folta, men folta.

Ascolta.

La figlia dell’ aria

è muta ; ma la figlia

del limo lontana,

la rana,

canta nell’ ombra più fonda,

chi sa dove, chi sa dove !

E piove su le tue ciglia,

Ermione.

Piove su le tue ciglia nere

sì che par tu pianga

ma di piacere ; non bianca

ma quasi fatta virente,

par da scorza tu esca.

E tutta la vita è in noi fresca

aulente,

il cuor nel petto è come pèsca

intatta,

tra le pàlpebre gli occhi

son come polle tra l’erbe,

i denti negli alvèoli

son come mandorle acerbe.

E andiam di fratta in fratta,

or congiunti or disciolti

(e il verde vigor rude

ci allaccia i mallèoli

c’intrica i ginocchi)

chi sa dove, chi sa dove !

E piove su i nostri vólti

silvani,

piove su le nostre mani

ignude,

su i nostri vestimenti

leggieri,

su i freschi pensieri

che l’anima schiude

novella,

su la favola bella

che ieri

m’illuse, che oggi t’ illude,

o Ermione.

Gabriele D’Annunzio poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive C-D, D'Annunzio, Gabriele

Leo Vroman overleden

Leo Vroman (Gouda, 10 april 1915 – Fort Worth, 22 februari 2014) was dichter, prozaïst, essayist, illustrator en hematoloog. Hij studeerde biologie in Utrecht en vluchtte in 1940 naar Nederlands-Indië. In 1945 werd hij uit Japanse gevangenschap bevrijd en vestigde zich in Verenigde Staten, waar hij tot op de dag van vandaag woonde, samen met zijn vrouw Tineke. Vroman debuteerde in 1946 met de bundel Gedichten. Talloze publicaties en zowat alle belangrijke literaire prijzen heeft hij op zijn naam staan.

Ik wil je zo makkelijk niet kwijt,

zie je liefst een hele tijd

naliggen en zitten

alsof je zo pas nog die witte

zakdoek hebt uitgespreid

op het bolle slapende beest.

Helaas, dit zoek ik het meest:

het schadeloos besmetten

van je alledaagse leven

om je bij voorbeeld even

het optellen te beletten

van geld, het verdelen van pap.

Dit klinkt misschien als een grap,

een fladder-, een eiwitlicht,

of zelfs kodderig gedicht.

Het is mij dodelijke ernst.

(Leo Vroman 1959)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive U-V, In Memoriam, Vroman, Leo

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature