Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Tilt

Bij de muziek van Scott Walker

I

Slagschaduw van hand met potlood

over de ontcijfering van wat hier klinkt:

links en rechts brandbaar geheimen rollen

in elkaar tot wat een steekspel wordt.

Hij

daar met die neiging, veraf en zo dichtbij

zoals ik hier nu jou reeds weet,

beweegt zich buigend en verlangend

zinvol tasten in. Op zoek naar evenwicht.

II

Deze kluizenaar vermoedt onder kousen sproetjes.

Bezweert binnensmonds nachtmerries en

helt zoals hij denkt in cirkelend

weerkaatsen – luidop maar ongezien,

liefst.

Cimbalen laat hij klateren als water.

Toch hangt van dit geluid zijn leven amper af.

O the Luzerner Zeitung never sold out,

never sold out

III

Over zinnen laat hij zilvergrijze sluiers vallen.

Niemand vraagt waarom. Zo is het dan ook goed.

Zingen is voor deze stem geen afdoend woord:

plofjes adem blijven hangen tussen microfoon en

oren.

Dan zweeft hij tussen fluisteren en fluiten door

op weg naar waterweegbree, webben en de lippen

van een meisje dat met open mond probeert

een mooie ronde o te neuriën

IV

Wereldvreemde man schept eigen logica.

Wie die niet volgen kan mag heel gewoon

een straatje om. Zie je hem dan de pijn niet lijden

van monsters in de nacht, van schaduwen in

regen?

De monnik wist verhalen uit, tegels almaar donkerder

rond de voeten. Hoofdvol galmen wonderen.

In geval van dij, in geval van dij. Hij kust gaten

voor de kogels in geval van dij.

V

Zie hoe het zeil spant. Onder de verse huif

telt hij de rimpels in zijn handen, met die

van zijn vader vol overeenkomsten, net

als de verse verdragen voor toekomst.

Nat

de lakzegel nog. Krullend van heimwee

naar een tijd van jagers stort hij zich

een aanval binnen. Vurig smeedt hij daarin

gulle plannen. Vurig.

Bert Bevers

Verschenen in Gierik & Nieuw Vlaams Tijdschrift, Antwerpen, 1998

In memoriam Scott Walker (born Noel Scott Engel; January 9, 1943 – March 22, 2019)

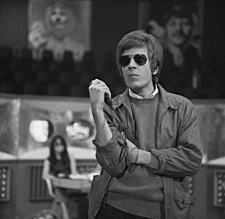

Photo: Scott Walker – Dutch TV programme Fenklup 1968 – Beeld en Geluid Wiki

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Archive W-X, Art & Literature News, Bevers, Bert, In Memoriam, Scott Walker

De Nasleep

Als dat schôon menske weer lillek is geworden.

Als oe bed zich niet onder oe kont bevindt.

Als het daglicht die hossende Rotterdammer verraadt,

Dan rest alleen nog maar de kater,

maar is uw Carnaval waarschijnlijk geslaagd.

De Kater…

Zou het licht alsjeblieft wat minder hard willen praten?

Ik kan mijn hoofdpijn niet zo goed meer verstaan..

Onias Landveld

Onias Landveld (Paramaribo, 1985) is een verhalenverteller. Hij schrijft, spreekt, dicht en inspireert. Vanaf aug 2017 is hij voor twee jaar de stadsdichter van Tilburg.

Onias Landveld (Paramaribo, 1985) is een verhalenverteller. Hij schrijft, spreekt, dicht en inspireert. Vanaf aug 2017 is hij voor twee jaar de stadsdichter van Tilburg.

Zijn talent deelt hij graag via concepten, workshops en spreek-cursussen. Maar het podium is waar hij het liefst staat. In 1989 ontvluchtte hij samen met zijn familie de Surinaamse burgeroorlog. Na 3 jaar te hebben gewoond in Utrecht, vertrok het gezin weer naar zijn geboorteland. Sinds 1998 woont hij in Tilburg.

Na jaren te hebben rondgedwaald ontdekte hij zijn liefde voor het gesproken woord. In 2015 mocht hij daarvoor de Van Dale Spoken Award voor storytelling ontvangen.

Het heeft hem nog meer gemotiveerd om naar mensen uit te reiken. Altijd zoekende om iemand te raken met een memorabele boodschap, blijft hij met woorden banden smeden. Hij houdt daarvan. Herkenning creëren door een zaadje te planten, gevoed met passie en identificatie.

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: *Concrete + Visual Poetry K-O, Archive K-L, Archive K-L, City Poets / Stadsdichters, Landveld, Onias

Onias Landveld Stadsdichter van Tilburg organiseert op 30 maart, de tweede editie van The Stage. Die avond zal hij met zijn podium te gast zijn bij het Tilt Festival in Theater De Nieuwe Vorst in Tilburg.

Het thema van de avond is “Zij is”, een knik naar de Boekenweek 2019, die ‘Moeder de vrouw’ als onderwerp heeft.

Het thema van de avond is “Zij is”, een knik naar de Boekenweek 2019, die ‘Moeder de vrouw’ als onderwerp heeft.

Met een aantal speciale gasten zal The Stage bezoekers die avond vermaken met poëzie, verhalen en muziek.

De stadsdichter is het podium gestart omdat hij iets wil achterlaten als hij in Augustus dit jaar afzwaait.

Onias Landveld vindt dat woordkunst in een stad als Tilburg een plaats moet blijven hebben. Daarom is hij vorig jaar dit evenement gestart dat zijn vaste plek in de Nwe Vorst heeft.

Op 30 maart staan on Stage: Zeinab El Bouni, Aminata Cairo, LouLou Elisabettie, Lev Avitan, Whitney Muanza Sabina Lukovic en Tessa Gabriëls.

Onias Landveld & The Stage

Tilt Festival in Theater De Nieuwe Vorst

Willem II straat – Tilburg.

Aanvang: 20:45

Einde: 22:45

Kaarten verkrijgbaar via de website van Tilt of de Nieuwe Vorst

# website theater de nieuwe vorst

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: *Concrete + Visual Poetry K-O, - Book Lovers, Archive K-L, Archive K-L, Art & Literature News, City Poets / Stadsdichters, Landveld, Onias, STREET POETRY, THEATRE, Tilt Festival Tilburg

Von Liebe

Am Abend sprach das Meer und flüsterte:

Ihr schönen Mägdelein, erzählt mir leise,

Ich will die Liebe wissen! Redet mir

So von der Liebe, gleich als sollte ich

Dran sterben, so als müsst’ in Ruhe ich

Versinken dran, als könnte sie vorm Sturme

Mich schützen, dass so wütend er nicht mehr

Auf mich sich stürzte! – O! so sprachen da

Die Mägdelein, – Wir wissen wahrlich nicht,

Du armes Meer, ob wir erzählen dürfen;

Denn nimmermehr würdst du in wilder Kraft

Die Schiffe schleudern wollen, und der Felsen

Sorgenumwölbte Stirn mit Schaume peitschen,

Noch wälzen unter jähe, grüne Klippen

Der Sterne Blicken. Glaub’ uns Meer, Du wolltest

So mächtig nimmer sein, so scheu und spröde,

In deinen Schoß und in dein Herz nicht mehr

Die schlafumfangnen Menschenherzen saugen.

Du würdest dann gleich uns den Himmel ansehn,

Und ihn nicht sehen, lächeln, wie der Wind

Vorüberweht, und weinen, weil die Sonne

Aufgeht! Nein! wir werden nichts erzählen!

Carmen Sylva

(1843-1916)

Von Liebe

Gedicht

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Archive S-T, CLASSIC POETRY

`Wat een allemachtig mooie bliksem’, zegt Tijger vol bewondering. Het hele dorp wordt geraakt door vuurpijlen die sissend in de grond slaan.

`Onweer is sprookjesweer’, zegt Thija.

`Onweer is sprookjesweer’, zegt Thija.

Door het raampje van de zolder is het uitzicht op de wereld altijd sprookjesachtig, maar vooral nu, nu de bliksem het dorp wil afbranden en de donkere bossen aan de bovenloop van de Wijer in een witte gloed zet.

In hun bijna geluiddichte schuilplaats op de zolder van de molen horen ze het onweer nauwelijks, maar zien ze wel de bliksem wanneer die als een drietand boven het dorp staat. Hij vonkt langs de bliksemafleider van de kerk. De vlammen spatten van het beeld van Christoffel dat boven op de toren staat en die het dorp bewaakt, met op zijn schouder het kindje Jezus dat al een paar honderd jaar wacht om over de Wijer te worden gedragen.

Thija leest voor uit een van de bijbelboeken die in een doos op de zolder staan. Ze hebben er pas twee gelezen. De rest moet nog.

`Zodra Izebel, de weduwe van koning Achab van Juda, hoorde dat Jehoe, de nieuwe koning van Juda en moordenaar van haar man, haar kwam bezoeken, liet zij haar huis beschilderen, plantte bloemen in haar tuin en nodigde vrouwen in haar huis.’

`Dat zijn veel komma’s in één zin’, zegt Mels.

`Ik kan niet anders lezen dan dat wat er staat’, zegt Thija. Ze leest verder.

`Deze vrouwen waren in de hogere kringen zeer geliefd. Zij verstonden de kunst van het verleiden en maakten daar gebruik van.’

`Hoeren dus’, zegt Tijger. `Net als in de bunker.’

`Op de dag van Jehoes aankomst, verfde Izebel haar ogen zwart, haar lippen rood en haar nagels paars.’ Thija doet een vinger op haar lippen om te voorkomen dat Tijger daar weer opmerkingen over maakt. `Ze maakte haar kapsel in orde, kleedde zich in een jurk van doorschijnende zijde, sierde zich met paarlen, robijnen en blauw glanzende brokken aquamarijn. Daarna ging ze op het met bloemen gestikte kussen voor het venster zitten en wachtte af. Toen ze Jehoe zag naderen, raakte ze zeer opgewonden. “Hoe gaat het de nieuwe koning van Juda?” vroeg ze. “Hoe gaat het de moordenaar van mijn man? Het zal wel goed met hem zijn. De Heer onze God is met hem, want hij heeft het land een dienst bewezen door mijn man Achab te vermoorden.”‘

`Ze had wel lef’, zegt Tijger.

`Toen Jehoe haar hoorde, riep hij woedend tegen zijn soldaten: “Gooi dat kreng het raam uit!” De soldaten grepen Izebel en gooiden haar op de binnenplaats. Daar liet Jehoe haar door de paarden vertrappen. Haar bloed spoot tegen de muur. Wilde honden vraten haar vlees. Haar hersenen werden verzameld door een bedelaar die ermee aan de haal ging.

In de volgende dagen liet Jehoe alle zonen van Achab vermoorden. Achab had zeventig zonen, verwekt bij Izebel, slavinnen en publieke vrouwen. Hij had geen dochters, omdat Izebel nooit een dochter gebaard had. De dochters die Achab verwekt had bij slavinnen en publieke vrouwen, had hij voor de leeuwen laten werpen. Volgens de wetten van het volk waren ze een doorn in het oog van God. De zonen van Achab woonden verspreid over heel Israël, bij oude leermeesters. Ze werden door Jehoes soldaten neergestoken en ontmand. Hun hoofden werden afgehouwen en verpakt in manden naar Jehoe gezonden. Jehoe voerde de hoofden van Achabs zonen aan de wilde dieren. Zo kwam er een einde aan het geslacht van Achab.’

Verbijsterd kijken ze elkaar aan.

`Waarom staat zoiets in de bijbel?’ vraagt Tijger.

`De bijbel is een geschiedenisboek’, zegt Thija.

`Denk je dat dit echt is gebeurd?’

`Natuurlijk. De mensen leefden als beesten.’

`Net als in China?’

`Net als in China.’

`Lees nog maar een verhaal. Met dit weer kunnen we toch niet weg. Maar wel een verhaal dat minder gruwelijk is.’

Thija slaat het boek weer open, maar stokt in haar beweging als de wind de pannen rijtje voor rijtje oplicht en ze roffelend weer op hun plek laat vallen. Een paar pannen vallen kapot. De regen slaat als een waterval op de ruit. Het is echt noodweer.

De bliksem treft de kerk opnieuw. Het kind op de schouder van Christoffel staat in brand.

`Ik hoor dat Jezus “help” roept’, zegt Tijger

`Hierboven horen we niks’, zegt Mels.

`We horen Hem wel’, zegt Thija. `Hij is nog maar een kind. We horen het als Hij angst heeft. Hij roept naar ons. Jezus kan dat. God kan alles.’

`Hij staat echt in brand’, zegt Mels, nauwelijks gelovend wat hij ziet. `De toren brandt.’

Ze zien dat Christoffel wankelt en naar voren helt. Even houdt hij zich vast aan de antenne op zijn rug en draait een halve slag om zijn as. Dan valt hij samen met het kind naar beneden. Hun val wordt gebroken door uitstekende draden en haken, dan tuimelen ze in de afgrond tussen de daken van het dorp.

`Jezus komt thuis bij Zijn Vader op het altaar’, zegt Thija bleek. Ze glijdt van de stapel meelzakken af, knielt neer, haar hoofd gebogen en bidt.

De jongens houden hun adem in. Mels weet dat dit een moment is waarop de wereld kan blijven stilstaan.

Op zolder is het nog stiller dan het al was. Verbijsterd kijken ze naar de vlammen die uit de toren slaan en over het dak van de kerk dansen. In een paar tellen zetten ze het hele gebouw in lichterlaaie.

Ton van Reen: Het diepste blauw (095)

wordt vervolgd

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Het diepste blauw, Archive Q-R, Reen, Ton van

A Day

I’ll tell you how the sun rose, —

A ribbon at a time.

The steeples swam in amethyst,

The news like squirrels ran.

The hills untied their bonnets,

The bobolinks begun.

Then I said softly to myself,

“That must have been the sun!”

But how he set, I know not.

There seemed a purple stile

Which little yellow boys and girls

Were climbing all the while

Till when they reached the other side,

A dominie in gray

Put gently up the evening bars,

And led the flock away.

Emily Dickinson

(1830-1886)

A Day

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive C-D, Dickinson, Emily

De 84ste editie van de Boekenweek vindt plaats van zaterdag 23 maart tot en met zondag 31 maart en heeft De moeder de vrouw als thema naar het gelijknamige gedicht van Martinus Nijhoff.

Voor de Boekenweek 2019 schreef Jan Siebelink het Boekenweekgeschenk Jas van belofte, dat tijdens de Boekenweek bij besteding van ten minste €12,50 aan Nederlandstalige boeken door de boekhandel cadeau wordt gedaan.

Voor de Boekenweek 2019 schreef Jan Siebelink het Boekenweekgeschenk Jas van belofte, dat tijdens de Boekenweek bij besteding van ten minste €12,50 aan Nederlandstalige boeken door de boekhandel cadeau wordt gedaan.

Het Boekenweekessay is geschreven door Murat Isik en heeft de titel Mijn moeders strijd. Tijdens de Boekenweek is het voor € 3,75 verkrijgbaar in de boekwinkel.

Op 31 maart, de laatste zondag van de Boekenweek, kunnen reizigers traditiegetrouw op het vertoon van het Boekenweekgeschenk gratis met de trein reizen.

Op 31 maart, de laatste zondag van de Boekenweek, kunnen reizigers traditiegetrouw op het vertoon van het Boekenweekgeschenk gratis met de trein reizen.

De moeder de vrouw

Het thema van de Boekenweek 2019 is ontleend aan het beroemde gedicht van Martinus Nijhoff ‘De moeder de vrouw’. Tevens is het Boekenweekthema een verwijzing naar de bundel De moeder de vrouw, met daarin twee romans (Ontaarde moeders en Mijn zoon heeft een seksleven en ik lees mijn moeder Roodkapje voor) over moederschap van de onlangs overleden Renate Dorrestein.

# meer informatie op website boekenweek

Boekweek 2019

van 23 – 31 maart

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book Lovers, - Book News, - Book Stories, - Bookstores, Art & Literature News, Boekenweek, Jan Siebelink, Nijhoff, Martinus

De schrijvers Jan Leyers, Ilja Leonard Pfeijffer en Jolande Withuis zijn genomineerd voor de E. du Perronprijs 2018. De prijs wordt toegekend aan schrijvers, kunstenaars of instellingen die met een cultuuruiting in brede zin een bijdrage leveren aan een inclusieve samenleving. De uitreiking vindt plaats op dinsdagavond 16 april in de Glazen Zaal in de LocHal in Tilburg. Dan houdt Gloria Wekker de achtste E. du Perronlezing.

Jan Leyers ‒ Allah in Europa. Het reisverslag van een ongelovige (Uitgeverij Das Mag)

Jan Leyers ‒ Allah in Europa. Het reisverslag van een ongelovige (Uitgeverij Das Mag)

Leyers doet in dit boek verslag van een reis door Europa waarin hij op zoek gaat naar ‘een Europese versie van de islam’. Vier maanden lang wordt er gesproken met traditionele gelovigen en nieuwe bekeerlingen. Allah in Europa leest als een spannend verslag van gesprekken waarin verschillende denkbeelden tegen elkaar afgewogen worden. Knap is dat het boek nergens belerend of dwingend wordt, hoewel het overduidelijk een pleidooi is voor een open multicultureel Europa, dat de lezer aanzet tot nadenken.

Ilja Leonard Pfeijffer ‒ Grand Hotel Europa (Uitgeverij De Arbeiderspers)

Ilja Leonard Pfeijffer ‒ Grand Hotel Europa (Uitgeverij De Arbeiderspers)

In deze roman neemt Pfeijffer ons mee naar een hotel ergens in Europa waarin zijn alter ego zich verschanst na een stukgelopen liefde. Het hotel is vergane glorie, oude geschiedenis en een metaforisch beeld voor het continent, waarvan de geschiedenis fenomenaal is, maar het heden op allerlei manier ontspoort: er is te veel consumentisme, geen engagement, er zijn geen nieuwe idealen. Pfeijffer verweeft verschillende verhaallijnen met elkaar, en is op zijn best in de essayistische passages waarin hij kritiek geeft op het hedendaagse Europa en vooral op het massatoerisme.

Jolande Withuis ‒ Raadselvader. Kind in de koude oorlog (Uitgeverij De Bezige Bij)

Jolande Withuis ‒ Raadselvader. Kind in de koude oorlog (Uitgeverij De Bezige Bij)

Withuis schreef een indringende biografie over haar vader Berry Withuis (1920-2009), die tegelijk een autobiografische reflectie biedt. De vader was communist en redacteur van de Waarheid. Haar communistische jeugd en de loyaliteit jegens haar ouders hebben Withuis geleerd dat er verschillende kanten zitten aan een historisch narratief. Noch het ontkennen van de slechte behandeling van communisten in Nederland tijdens de Koude Oorlog, noch het slachtofferisme van de zijde van communisten zelf, is de waarheid. Maar ook leert zij dat via het eigen verhaal de geschiedenis van anderen aanknopingspunten biedt en legt ze uit dat totalitaire overtuigingen mensen verleiden onmenselijke misdaden te begaan en het eigen ethische kompas uit te schakelen.

E. du Perronprijs

De E. du Perronprijs is een initiatief van de gemeente Tilburg, de Tilburg School of Humanities & Digital Sciences en Kunstloc Brabant. De prijs is bedoeld voor personen of instellingen die, net als schrijver Du Perron, grenzen signaleren en doorbreken die wederzijds begrip tussen verschillende bevolkingsgroepen in de weg staan. De prijs bestaat uit een geldbedrag van 2500 euro en een textielobject, ontworpen door studio ‘by aaaa’ (Moyra Besjes en Natasja Lauwers) en vervaardigd bij het TextielMuseum. In 2017 won Margot Vanderstraeten de prijs voor haar boek Mazzel tov. Andere laureaten waren onder meer Stefan Hertmans (2016), Ilja Leonard Pfeijffer (2015), Warna Oosterbaan & Theo Baart (2014), Mohammed Benzakour (2013), Koen Peeters (2012) en Ramsey Nasr (2011).

E. du Perronlezing

Professor dr. Gloria Wekker is emeritus hoogleraar Gender en Etniciteit aan de faculteit Geesteswetenschappen van de Universiteit Utrecht. Ze houdt, op 16 april, na Antjie Krog, Paul Scheffer, Job Cohen, Sheila Sitalsing, Herman van Rompuy, Arnon Grunberg en Marja Pruis de achtste E. du Perronlezing.

Voor het bijwonen van de uitreiking kunnen belangstellenden en genodigden zich aanmelden via www.kunstlocbrabant.nl/eduperron

Meer informatie over de prijs vindt u op: www.tilburguniversity.edu/duperronprijs

# Literaire prijzen

E. du Perronprijs 2018

Jan Leyers

Ilja Leonard Pfeijffer

Jolande Withuis

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book Lovers, - Book News, - Bookstores, Archive K-L, Archive O-P, Archive W-X, Art & Literature News, Awards & Prizes, Literary Events

In the sequence of poems comprising Annie Guthrie’s first book, the quest for the meaning of human consciousness and its tangled subjectivity is drawn as a slow-building narrative of the mystic experience.

In the sequence of poems comprising Annie Guthrie’s first book, the quest for the meaning of human consciousness and its tangled subjectivity is drawn as a slow-building narrative of the mystic experience.

The journey enacted is that of the self as character, who encounters insurmountable mysteries in a breaking selfhood.

A dossier of contemplative exploration, THE GOOD DARK chronicles an immersive search in three acts: Unwitting, Chorus, and Body: stations through which the character must pass, and where she is accumulatively confessed, compounded and erased.

the gossip

I don’t always want what we have, she is saying.

Outside, dark clouds, fish hopping, tilling waves

back from shore. He is silent.

Sometimes more is happening, he says, finally.

The sun’s coming up, she says. Look how the light is kept.

I’d like to keep it up, he says.

Don’t make apart when otherwise the same, he says.

She is silent, tilling shore back from shore.

Don’t give darkness a face, he says, darkening.

Annie Guthrie is a writer and jeweler living in Tucson. She has a metalsmithing studio at Splinter Brothers Warehouse and can be found through her website, www.annieguthrie.net. She teaches at the University of Arizona Poetry Center and also mentors select students wishing to apprentice in poetry or to further their art projects through her courses in “Oracular Writing.”

The Good Dark

by Annie Guthrie

Paperback: 68 pages

Publisher: Tupelo Press, Inc.

2015

Language: English

ISBN-10: 1936797593

ISBN-13: 978-1936797592

Categories: Poetry

$16.95

# more poetry

The Good Dark

by Annie Guthrie

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Bookstores, Archive G-H, Archive G-H, Art & Literature News

Mrs. Whitehead

But you like it.

They can’t any of them be quite as bad because they learned french but I never did.

He doesn’t look dead at all.

The wind might have blown him.

He comes from that direction. That’s the way.

They are not knotted. Have you smelt it. What would you suggest, your advice I have come across three or four.

So they are the others.

Separate them.

It does make one come, he is extraordinarily charming and endearing once of twice only twice I think.

He is not staying out that’s hard beside that what does he do.

That’s long for his mother.

She travelled from this rest. She crocheted from this nest.

She crocheted from this nest. I thought it wasn’t ever.

It’s one of my favorite ones this.

And yet not this.

Isn’t it funny.

It isn’t.

Break or breaking, very fair, break or very wanting.

I tried it this way before.

Very difficult to change extra places and yet I can agree. I can agree by that. I rest this piece of it and it’s nearly the same climate. I will tell you why they want a real door. They choose it.

They do so and very pure water. They are safe when they take a bath. Oh it is very. Oh it is.

In a way a vest.

I do think you get what you want.

Corrections.

It is eleven weeks from the middle of September. I glance in a way.

It is eleven weeks from the middle of September.

Total recollect others.

I glance at and I can recollect others. I make a division neatly, I close.

What is wrong with not blue. That is right with apples. Apples four. For. Fore.

Before that.

Next stretching.

Next for that leaf stretching.

I do not state leaf.

I like to beg very much stream.

Not exactly in state.

Understate.

All in so.

They expect all the blues to take of all the other families, the whites are extra they are beside all that, they make a little house and through and beside that they live in Paris.

Hardly enough for wood.

Not a color even.

By now a change of grass and wedding rings and all but the rest plan. I don’t care I won’t look.

I am not sure that yellow is good. I am tall.

Allow that. I don’t want any more out in conversation.

I can be careful.

Not within wearing it.

I cannot say to stay.

No please don’t get up.

And now that.

Yes I see.

Did you pay him for that whether for a spider and such splendor and indeed quitting. I meant to gather.

I see it I see it.

Please ocean spoke please Helen land please take it away.

I saw a spoken leave leaf and flowers made vegetables and foliage in soil. I saw representative mistakes and glass cups, I saw a whole appearance of respectable refugees, I did not ask actors I asked pearls, I did not choose to ask trains, I was satisfied with celebrated ransoms. I cannot deny Bertie Henschel is coming tomorrow. Saturdays are even. There is a regular principle, if you mention it you mention what happened.

What do you make of it.

You exceed all hope and all praise.

Stein, Gertrude

(1874-1946)

Mrs. Whitehead

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Archive S-T, Gertrude Stein, Stein, Gertrude

DEATH TO THE FASCIST INSECT is a compilation of the writings and transcribed recordings of the Symbionese Liberation Army (1973–75), a radical left-wing group based in the Bay Area of California. This publication chronicles the militant, if half-baked, political theories that inspired the SLA, as well as the ways that the SLA used violence and manipulation of the media to further the group’s goal of provoking armed revolution from the underground.

Founded by escaped convict Donald DeFreeze, aka Field Marshal Cinque, the SLA was mostly composed of young, largely white and middle-class men and women, whose stated aim was to destroy all forms of racism, sexism, and capitalism. One of the SLA’s first acts was the murder of the Oakland superintendent of schools; SLA members went on to kidnap newspaper heiress Patricia Hearst, demand millions of dollars from her wealthy family for free food for “people in need,” and rob a bank in San Francisco with Hearst. Most of the SLA, including DeFreeze, died in a fire after a gun battle with police in Los Angeles, while Hearst was later pardoned.

Founded by escaped convict Donald DeFreeze, aka Field Marshal Cinque, the SLA was mostly composed of young, largely white and middle-class men and women, whose stated aim was to destroy all forms of racism, sexism, and capitalism. One of the SLA’s first acts was the murder of the Oakland superintendent of schools; SLA members went on to kidnap newspaper heiress Patricia Hearst, demand millions of dollars from her wealthy family for free food for “people in need,” and rob a bank in San Francisco with Hearst. Most of the SLA, including DeFreeze, died in a fire after a gun battle with police in Los Angeles, while Hearst was later pardoned.

This publication features an introduction by editor John Brian King, a chronology of the SLA, the writings and transcribed recordings of the group presented in the context of events at the time, and a fifty-page appendix of notable articles, letters, and other texts related to the SLA.

John Brian King is a writer, photographer, and filmmaker. His works include the nonfiction book Lustmord: The Writings and Artifacts of Murderers (1997), the photography books LAX: Photographs of Los Angeles 1980-84 (2015) and Nude Reagan (2016), and the feature film Redlands (2014).

Death to the Fascist Insect

John Brian King, Editor

Publisher: Spurl Editions

Product Number: 9781943679089

ISBN 978-1-943679-08-9

SKU #: C17B

Binding: Paperback

Pages: 232

Literary Nonfiction

California Interest

African & African American Studies

Political Theory. Crime

Price: $ 18.50

Pub Date: 3/13/2019

# New books

SLA – Symbionese Liberation Army

Death to the Fascist Insect

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Bookstores, Archive K-L, Art & Literature News, CRIME & PUNISHMENT, Racism

‘Mijn overtuigingen zijn beperkt, maar wel intens. Ik geloof in de mogelijkheden van het speciale koninkrijk. Ik geloof in de liefde,’ schreef Michel Houellebecq eens.

De depressieve verteller van Serotonine zou het daar zonder voorbehoud mee eens zijn.

De depressieve verteller van Serotonine zou het daar zonder voorbehoud mee eens zijn.

Zijn verhaal vindt plaats in een Frankrijk dat zijn tradities aan het verkwanselen is, zijn steden ontdoet van hun charme en zijn platteland verwoest tot de volksopstand erop volgt.

Hij vertelt over zijn leven als landbouwingenieur, zijn vriendschap met een boer van adel (een onvergetelijk personage – zijn dubbelganger in spiegelbeeld), over het falen van hun jeugdige idealen, de misschien wel dwaze hoop een verloren vrouw terug te vinden.

Deze roman over de puinhopen van een wereld zonder goedheid, zonder solidariteit, met onbeheersbaar geworden veranderingen, is ook een roman over wroeging en spijt. ‘Niemand in het Westen zal nog gelukkig zijn.’

Michel Houellebecq (1958) is Frankrijks onbetwiste sterschrijver van dit moment. Hij publiceerde essays en poëzie voordat hij zich in 1994 met de roman De wereld als markt en strijd, die bekroond werd met diverse prijzen, opwierp als belofte van de Franse letteren. Die status bevestigde hij met Elementaire deeltjes (Prix Novembre en Impact Dublin Literary Award), dat hem terecht de faam van groot schrijver bezorgde, en Platform. In 2011 en 2015 verschenen zijn grote romans De kaart en het gebied en Onderworpen. Zijn veelvuldig bekroonde en wereldwijd vertaalde werk is in het Nederlands vertaald door Martin de Haan. Sinds 1998 leeft Michel Houellebecq in zelfverkozen ballingschap in Ierland.

Serotonine

Literaire fictie

Auteur: Michel Houellebecq

Vertaler: Martin de Haan

Uitgeverij: De Arbeiderspers

NUR: 302

ISBN: 9789029529020

Hardcover

Taal: Nederlands

Bladzijden: 352 pp.

Prijs: € 22,50

Publicatiedatum: 21-03-2019

# New fiction

Michel Houellebecq

Serotonine

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Bookstores, Archive G-H, Art & Literature News, Michel Houellebecq

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature