Fleurs du Mal Magazine

.jpg)

James Joyce

(1882-1941)

A Little Cloud

Eight years before he had seen his friend off at the North Wall and wished him godspeed. Gallaher had got on. You could tell that at once by his travelled air, his well-cut tweed suit, and fearless accent. Few fellows had talents like his and fewer still could remain unspoiled by such success. Gallaher’s heart was in the right place and he had deserved to win. It was something to have a friend like that.

Little Chandler’s thoughts ever since lunch-time had been of his meeting with Gallaher, of Gallaher’s invitation and of the great city London where Gallaher lived. He was called Little Chandler because, though he was but slightly under the average stature, he gave one the idea of being a little man. His hands were white and small, his frame was fragile, his voice was quiet and his manners were refined. He took the greatest care of his fair silken hair and moustache and used perfume discreetly on his handkerchief. The half-moons of his nails were perfect and when he smiled you caught a glimpse of a row of childish white teeth.

As he sat at his desk in the King’s Inns he thought what changes those eight years had brought. The friend whom he had known under a shabby and necessitous guise had become a brilliant figure on the London Press. He turned often from his tiresome writing to gaze out of the office window. The glow of a late autumn sunset covered the grass plots and walks. It cast a shower of kindly golden dust on the untidy nurses and decrepit old men who drowsed on the benches; it flickered upon all the moving figures, on the children who ran screaming along the gravel paths and on everyone who passed through the gardens. He watched the scene and thought of life; and (as always happened when he thought of life) he became sad. A gentle melancholy took possession of him. He felt how useless it was to struggle against fortune, this being the burden of wisdom which the ages had bequeathed to him.

He remembered the books of poetry upon his shelves at home. He had bought them in his bachelor days and many an evening, as he sat in the little room off the hall, he had been tempted to take one down from the bookshelf and read out something to his wife. But shyness had always held him back; and so the books had remained on their shelves. At times he repeated lines to himself and this consoled him.

When his hour had struck he stood up and took leave of his desk and of his fellow-clerks punctiliously. He emerged from under the feudal arch of the King’s Inns, a neat modest figure, and walked swiftly down Henrietta Street. The golden sunset was waning and the air had grown sharp. A horde of grimy children populated the street. They stood or ran in the roadway or crawled up the steps before the gaping doors or squatted like mice upon the thresholds. Little Chandler gave them no thought. He picked his way deftly through all that minute vermin-like life and under the shadow of the gaunt spectral mansions in which the old nobility of Dublin had roystered. No memory of the past touched him, for his mind was full of a present joy.

He had never been in Corless’s but he knew the value of the name. He knew that people went there after the theatre to eat oysters and drink liqueurs; and he had heard that the waiters there spoke French and German. Walking swiftly by at night he had seen cabs drawn up before the door and richly dressed ladies, escorted by cavaliers, alight and enter quickly. They wore noisy dresses and many wraps. Their faces were powdered and they caught up their dresses, when they touched earth, like alarmed Atalantas. He had always passed without turning his head to look. It was his habit to walk swiftly in the street even by day and whenever he found himself in the city late at night he hurried on his way apprehensively and excitedly. Sometimes, however, he courted the causes of his fear. He chose the darkest and narrowest streets and, as he walked boldly forward, the silence that was spread about his footsteps troubled him, the wandering, silent figures troubled him; and at times a sound of low fugitive laughter made him tremble like a leaf.

He turned to the right towards Capel Street. Ignatius Gallaher on the London Press! Who would have thought it possible eight years before? Still, now that he reviewed the past, Little Chandler could remember many signs of future greatness in his friend. People used to say that Ignatius Gallaher was wild Of course, he did mix with a rakish set of fellows at that time. drank freely and borrowed money on all sides. In the end he had got mixed up in some shady affair, some money transaction: at least, that was one version of his flight. But nobody denied him talent. There was always a certain . . . something in Ignatius Gallaher that impressed you in spite of yourself. Even when he was out at elbows and at his wits’ end for money he kept up a bold face. Little Chandler remembered (and the remembrance brought a slight flush of pride to his cheek) one of Ignatius Gallaher’s sayings when he was in a tight corner:

“Half time now, boys,” he used to say light-heartedly. “Where’s my considering cap?”

That was Ignatius Gallaher all out; and, damn it, you couldn’t but admire him for it.

Little Chandler quickened his pace. For the first time in his life he felt himself superior to the people he passed. For the first time his soul revolted against the dull inelegance of Capel Street. There was no doubt about it: if you wanted to succeed you had to go away. You could do nothing in Dublin. As he crossed Grattan Bridge he looked down the river towards the lower quays and pitied the poor stunted houses. They seemed to him a band of tramps, huddled together along the riverbanks, their old coats covered with dust and soot, stupefied by the panorama of sunset and waiting for the first chill of night bid them arise, shake themselves and begone. He wondered whether he could write a poem to express his idea. Perhaps Gallaher might be able to get it into some London paper for him. Could he write something original? He was not sure what idea he wished to express but the thought that a poetic moment had touched him took life within him like an infant hope. He stepped onward bravely.

Every step brought him nearer to London, farther from his own sober inartistic life. A light began to tremble on the horizon of his mind. He was not so old, thirty-two. His temperament might be said to be just at the point of maturity. There were so many different moods and impressions that he wished to express in verse. He felt them within him. He tried weigh his soul to see if it was a poet’s soul. Melancholy was the dominant note of his temperament, he thought, but it was a melancholy tempered by recurrences of faith and resignation and simple joy. If he could give expression to it in a book of poems perhaps men would listen. He would never be popular: he saw that. He could not sway the crowd but he might appeal to a little circle of kindred minds. The English critics, perhaps, would recognise him as one of the Celtic school by reason of the melancholy tone of his poems; besides that, he would put in allusions. He began to invent sentences and phrases from the notice which his book would get. “Mr. Chandler has the gift of easy and graceful verse.” . . . “wistful sadness pervades these poems.” . . . “The Celtic note.” It was a pity his name was not more Irish-looking. Perhaps it would be better to insert his mother’s name before the surname: Thomas Malone Chandler, or better still: T. Malone Chandler. He would speak to Gallaher about it.

He pursued his revery so ardently that he passed his street and had to turn back. As he came near Corless’s his former agitation began to overmaster him and he halted before the door in indecision. Finally he opened the door and entered.

The light and noise of the bar held him at the doorways for a few moments. He looked about him, but his sight was confused by the shining of many red and green wine-glasses The bar seemed to him to be full of people and he felt that the people were observing him curiously. He glanced quickly to right and left (frowning slightly to make his errand appear serious), but when his sight cleared a little he saw that nobody had turned to look at him: and there, sure enough, was Ignatius Gallaher leaning with his back against the counter and his feet planted far apart.

“Hallo, Tommy, old hero, here you are! What is it to be? What will you have? I’m taking whisky: better stuff than we get across the water. Soda? Lithia? No mineral? I’m the same Spoils the flavour. . . . Here, garçon, bring us two halves of malt whisky, like a good fellow. . . . Well, and how have you been pulling along since I saw you last? Dear God, how old we’re getting! Do you see any signs of aging in me, eh, what? A little grey and thin on the top, what?”

Ignatius Gallaher took off his hat and displayed a large closely cropped head. His face was heavy, pale and cleanshaven. His eyes, which were of bluish slate-colour, relieved his unhealthy pallor and shone out plainly above the vivid orange tie he wore. Between these rival features the lips appeared very long and shapeless and colourless. He bent his head and felt with two sympathetic fingers the thin hair at the crown. Little Chandler shook his head as a denial. Ignatius Galaher put on his hat again.

“It pulls you down,” be said, “Press life. Always hurry and scurry, looking for copy and sometimes not finding it: and then, always to have something new in your stuff. Damn proofs and printers, I say, for a few days. I’m deuced glad, I can tell you, to get back to the old country. Does a fellow good, a bit of a holiday. I feel a ton better since I landed again in dear dirty Dublin. . . . Here you are, Tommy. Water? Say when.”

Little Chandler allowed his whisky to be very much diluted.

“You don’t know what’s good for you, my boy,” said Ignatius Gallaher. “I drink mine neat.”

“I drink very little as a rule,” said Little Chandler modestly. “An odd half-one or so when I meet any of the old crowd: that’s all.”

“Ah well,” said Ignatius Gallaher, cheerfully, “here’s to us and to old times and old acquaintance.”

They clinked glasses and drank the toast.

“I met some of the old gang today,” said Ignatius Gallaher. “O’Hara seems to be in a bad way. What’s he doing?”

“Nothing,” said Little Chandler. “He’s gone to the dogs.”

“But Hogan has a good sit, hasn’t he?”

“Yes; he’s in the Land Commission.”

“I met him one night in London and he seemed to be very flush. . . . Poor O’Hara! Boose, I suppose?”

“Other things, too,” said Little Chandler shortly.

Ignatius Gallaher laughed.

“Tommy,” he said, “I see you haven’t changed an atom. You’re the very same serious person that used to lecture me on Sunday mornings when I had a sore head and a fur on my tongue. You’d want to knock about a bit in the world. Have you never been anywhere even for a trip?”

“I’ve been to the Isle of Man,” said Little Chandler.

Ignatius Gallaher laughed.

“The Isle of Man!” he said. “Go to London or Paris: Paris, for choice. That’d do you good.”

“Have you seen Paris?”

“I should think I have! I’ve knocked about there a little.”

“And is it really so beautiful as they say?” asked Little Chandler.

He sipped a little of his drink while Ignatius Gallaher finished his boldly.

“Beautiful?” said Ignatius Gallaher, pausing on the word and on the flavour of his drink. “It’s not so beautiful, you know. Of course, it is beautiful. . . . But it’s the life of Paris; that’s the thing. Ah, there’s no city like Paris for gaiety, movement, excitement. . . . ”

Little Chandler finished his whisky and, after some trouble, succeeded in catching the barman’s eye. He ordered the same again.

“I’ve been to the Moulin Rouge,” Ignatius Gallaher continued when the barman had removed their glasses, “and I’ve been to all the Bohemian cafes. Hot stuff! Not for a pious chap like you, Tommy.”

Little Chandler said nothing until the barman returned with two glasses: then he touched his friend’s glass lightly and reciprocated the former toast. He was beginning to feel somewhat disillusioned. Gallaher’s accent and way of expressing himself did not please him. There was something vulgar in his friend which he had not observed before. But perhaps it was only the result of living in London amid the bustle and competition of the Press. The old personal charm was still there under this new gaudy manner. And, after all, Gallaher had lived, he had seen the world. Little Chandler looked at his friend enviously.

“Everything in Paris is gay,” said Ignatius Gallaher. “They believe in enjoying life, and don’t you think they’re right? If you want to enjoy yourself properly you must go to Paris. And, mind you, they’ve a great feeling for the Irish there. When they heard I was from Ireland they were ready to eat me, man.”

Little Chandler took four or five sips from his glass.

“Tell me,” he said, “is it true that Paris is so . . . immoral as they say?”

Ignatius Gallaher made a catholic gesture with his right arm.

“Every place is immoral,” he said. “Of course you do find spicy bits in Paris. Go to one of the students’ balls, for instance. That’s lively, if you like, when the cocottes begin to let themselves loose. You know what they are, I suppose?”

“I’ve heard of them,” said Little Chandler.

Ignatius Gallaher drank off his whisky and shook his had.

“Ah,” he said, “you may say what you like. There’s no woman like the Parisienne, for style, for go.”

“Then it is an immoral city,” said Little Chandler, with timid insistence, “I mean, compared with London or Dublin?”

“London!” said Ignatius Gallaher. “It’s six of one and half-a-dozen of the other. You ask Hogan, my boy. I showed him a bit about London when he was over there. He’d open your eye. . . . I say, Tommy, don’t make punch of that whisky: liquor up.”

“No, really. . . . ”

“O, come on, another one won’t do you any harm. What is it? The same again, I suppose?”

“Well . . . all right.”

“François, the same again. . . . Will you smoke, Tommy?”

Ignatius Gallaher produced his cigar-case. The two friends lit their cigars and puffed at them in silence until their drinks were served.

“I’ll tell you my opinion,” said Ignatius Gallaher, emerging after some time from the clouds of smoke in which he had taken refuge, “it’s a rum world. Talk of immorality! I’ve heard of cases, what am I saying?, I’ve known them: cases of . . . immorality. . . . ”

Ignatius Gallaher puffed thoughtfully at his cigar and then, in a calm historian’s tone, he proceeded to sketch for his friend some pictures of the corruption which was rife abroad. He summarised the vices of many capitals and seemed inclined to award the palm to Berlin. Some things he could not vouch for (his friends had told him), but of others he had had personal experience. He spared neither rank nor caste. He revealed many of the secrets of religious houses on the Continent and described some of the practices which were fashionable in high society and ended by telling, with details, a story about an English duchess, a story which he knew to be true. Little Chandler as astonished.

“Ah, well,” said Ignatius Gallaher, “here we are in old jog-along Dublin where nothing is known of such things.”

“How dull you must find it,” said Little Chandler, “after all the other places you’ve seen!”

Well,” said Ignatius Gallaher, “it’s a relaxation to come over here, you know. And, after all, it’s the old country, as they say, isn’t it? You can’t help having a certain feeling for it. That’s human nature. . . . But tell me something about yourself. Hogan told me you had . . . tasted the joys of connubial bliss. Two years ago, wasn’t it?”

Little Chandler blushed and smiled.

“Yes,” he said. “I was married last May twelve months.”

“I hope it’s not too late in the day to offer my best wishes,” said Ignatius Gallaher. “I didn’t know your address or I’d have done so at the time.”

He extended his hand, which Little Chandler took.

“Well, Tommy,” he said, “I wish you and yours every joy in life, old chap, and tons of money, and may you never die till I shoot you. And that’s the wish of a sincere friend, an old friend. You know that?”

“I know that,” said Little Chandler.

“Any youngsters?” said Ignatius Gallaher.

Little Chandler blushed again.

“We have one child,” he said.

“Son or daughter?”

“A little boy.”

Ignatius Gallaher slapped his friend sonorously on the back.

“Bravo,” he said, “I wouldn’t doubt you, Tommy.”

Little Chandler smiled, looked confusedly at his glass and bit his lower lip with three childishly white front teeth.

“I hope you’ll spend an evening with us,” he said, “before you go back. My wife will be delighted to meet you. We can have a little music and, , ”

“Thanks awfully, old chap,” said Ignatius Gallaher, “I’m sorry we didn’t meet earlier. But I must leave tomorrow night.”

“Tonight, perhaps . . . ?”

“I’m awfully sorry, old man. You see I’m over here with another fellow, clever young chap he is too, and we arranged to go to a little card-party. Only for that . . . ”

“O, in that case . . . ”

“But who knows?” said Ignatius Gallaher considerately. “Next year I may take a little skip over here now that I’ve broken the ice. It’s only a pleasure deferred.”

“Very well,” said Little Chandler, “the next time you come we must have an evening together. That’s agreed now, isn’t it?”

“Yes, that’s agreed,” said Ignatius Gallaher. “Next year if I come, parole d’honneur.”

“And to clinch the bargain,” said Little Chandler, “we’ll just have one more now.”

Ignatius Gallaher took out a large gold watch and looked a it.

“Is it to be the last?” he said. “Because you know, I have an a.p.”

“O, yes, positively,” said Little Chandler.

“Very well, then,” said Ignatius Gallaher, “let us have another one as a deoc an doruis, that’s good vernacular for a small whisky, I believe.”

Little Chandler ordered the drinks. The blush which had risen to his face a few moments before was establishing itself. A trifle made him blush at any time: and now he felt warm and excited. Three small whiskies had gone to his head and Gallaher’s strong cigar had confused his mind, for he was a delicate and abstinent person. The adventure of meeting Gallaher after eight years, of finding himself with Gallaher in Corless’s surrounded by lights and noise, of listening to Gallaher’s stories and of sharing for a brief space Gallaher’s vagrant and triumphant life, upset the equipoise of his sensitive nature. He felt acutely the contrast between his own life and his friend’s and it seemed to him unjust. Gallaher was his inferior in birth and education. He was sure that he could do something better than his friend had ever done, or could ever do, something higher than mere tawdry journalism if he only got the chance. What was it that stood in his way? His unfortunate timidity He wished to vindicate himself in some way, to assert his manhood. He saw behind Gallaher’s refusal of his invitation. Gallaher was only patronising him by his friendliness just as he was patronising Ireland by his visit.

The barman brought their drinks. Little Chandler pushed one glass towards his friend and took up the other boldly.

“Who knows?” he said, as they lifted their glasses. “When you come next year I may have the pleasure of wishing long life and happiness to Mr. and Mrs. Ignatius Gallaher.”

Ignatius Gallaher in the act of drinking closed one eye expressively over the rim of his glass. When he had drunk he smacked his lips decisively, set down his glass and said:

“No blooming fear of that, my boy. I’m going to have my fling first and see a bit of life and the world before I put my head in the sack, if I ever do.”

“Some day you will,” said Little Chandler calmly.

Ignatius Gallaher turned his orange tie and slate-blue eyes full upon his friend.

“You think so?” he said.

“You’ll put your head in the sack,” repeated Little Chandler stoutly, “like everyone else if you can find the girl.”

He had slightly emphasised his tone and he was aware that he had betrayed himself; but, though the colour had heightened in his cheek, he did not flinch from his friend’s gaze. Ignatius Gallaher watched him for a few moments and then said:

“If ever it occurs, you may bet your bottom dollar there’ll be no mooning and spooning about it. I mean to marry money. She’ll have a good fat account at the bank or she won’t do for me.”

Little Chandler shook his head.

“Why, man alive,” said Ignatius Gallaher, vehemently, “do you know what it is? I’ve only to say the word and tomorrow I can have the woman and the cash. You don’t believe it? Well, I know it. There are hundreds, what am I saying?, thousands of rich Germans and Jews, rotten with money, that’d only be too glad. . . . You wait a while my boy. See if I don’t play my cards properly. When I go about a thing I mean business, I tell you. You just wait.”

He tossed his glass to his mouth, finished his drink and laughed loudly. Then he looked thoughtfully before him and said in a calmer tone:

“But I’m in no hurry. They can wait. I don’t fancy tying myself up to one woman, you know.”

He imitated with his mouth the act of tasting and made a wry face.

“Must get a bit stale, I should think,” he said.

Little Chandler sat in the room off the hall, holding a child in his arms. To save money they kept no servant but Annie’s young sister Monica came for an hour or so in the morning and an hour or so in the evening to help. But Monica had gone home long ago. It was a quarter to nine. Little Chandler had come home late for tea and, moreover, he had forgotten to bring Annie home the parcel of coffee from Bewley’s. Of course she was in a bad humour and gave him short answers. She said she would do without any tea but when it came near the time at which the shop at the corner closed she decided to go out herself for a quarter of a pound of tea and two pounds of sugar. She put the sleeping child deftly in his arms and said:

“Here. Don’t waken him.”

A little lamp with a white china shade stood upon the table and its light fell over a photograph which was enclosed in a frame of crumpled horn. It was Annie’s photograph. Little Chandler looked at it, pausing at the thin tight lips. She wore the pale blue summer blouse which he had brought her home as a present one Saturday. It had cost him ten and elevenpence; but what an agony of nervousness it had cost him! How he had suffered that day, waiting at the shop door until the shop was empty, standing at the counter and trying to appear at his ease while the girl piled ladies’ blouses before him, paying at the desk and forgetting to take up the odd penny of his change, being called back by the cashier, and finally, striving to hide his blushes as he left the shop by examining the parcel to see if it was securely tied. When he brought the blouse home Annie kissed him and said it was very pretty and stylish; but when she heard the price she threw the blouse on the table and said it was a regular swindle to charge ten and elevenpence for it. At first she wanted to take it back but when she tried it on she was delighted with it, especially with the make of the sleeves, and kissed him and said he was very good to think of her.

Hm! . . .

He looked coldly into the eyes of the photograph and they answered coldly. Certainly they were pretty and the face itself was pretty. But he found something mean in it. Why was it so unconscious and ladylike? The composure of the eyes irritated him. They repelled him and defied him: there was no passion in them, no rapture. He thought of what Gallaher had said about rich Jewesses. Those dark Oriental eyes, he thought, how full they are of passion, of voluptuous longing! . . . Why had he married the eyes in the photograph?

He caught himself up at the question and glanced nervously round the room. He found something mean in the pretty furniture which he had bought for his house on the hire system. Annie had chosen it herself and it reminded him of her. It too was prim and pretty. A dull resentment against his life awoke within him. Could he not escape from his little house? Was it too late for him to try to live bravely like Gallaher? Could he go to London? There was the furniture still to be paid for. If he could only write a book and get it published, that might open the way for him.

A volume of Byron’s poems lay before him on the table. He opened it cautiously with his left hand lest he should waken the child and began to read the first poem in the book:

Hushed are the winds and still the evening gloom,

Not e’en a Zephyr wanders through the grove,

Whilst I return to view my Margaret’s tomb

And scatter flowers on the dust I love.

He paused. He felt the rhythm of the verse about him in the room. How melancholy it was! Could he, too, write like that, express the melancholy of his soul in verse? There were so many things he wanted to describe: his sensation of a few hours before on Grattan Bridge, for example. If he could get back again into that mood. . . .

The child awoke and began to cry. He turned from the page and tried to hush it: but it would not be hushed. He began to rock it to and fro in his arms but its wailing cry grew keener. He rocked it faster while his eyes began to read the second stanza:

Within this narrow cell reclines her clay,

That clay where once . . .

It was useless. He couldn’t read. He couldn’t do anything. The wailing of the child pierced the drum of his ear. It was useless, useless! He was a prisoner for life. His arms trembled with anger and suddenly bending to the child’s face he shouted:

“Stop!”

The child stopped for an instant, had a spasm of fright and began to scream. He jumped up from his chair and walked hastily up and down the room with the child in his arms. It began to sob piteously, losing its breath for four or five seconds, and then bursting out anew. The thin walls of the room echoed the sound. He tried to soothe it but it sobbed more convulsively. He looked at the contracted and quivering face of the child and began to be alarmed. He counted seven sobs without a break between them and caught the child to his breast in fright. If it died! . . .

The door was burst open and a young woman ran in, panting.

“What is it? What is it?” she cried.

The child, hearing its mother’s voice, broke out into a paroxysm of sobbing.

“It’s nothing, Annie . . . it’s nothing. . . . He began to cry . . . ”

She flung her parcels on the floor and snatched the child from him.

“What have you done to him?” she cried, glaring into his face.

Little Chandler sustained for one moment the gaze of her eyes and his heart closed together as he met the hatred in them. He began to stammer:

“It’s nothing. . . . He . . . he began to cry. . . . I couldn’t . . . I didn’t do anything. . . . What?”

Giving no heed to him she began to walk up and down the room, clasping the child tightly in her arms and murmuring:

“My little man! My little mannie! Was ’ou frightened, love? . . . There now, love! There now!… Lambabaun! Mamma’s little lamb of the world! . . . There now!”

Little Chandler felt his cheeks suffused with shame and he stood back out of the lamplight. He listened while the paroxysm of the child’s sobbing grew less and less; and tears of remorse started to his eyes.

.jpg)

James Joyce: A Little Cloud

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Archive I-J, Joyce, James, Joyce, James

.jpg)

W i l l i a m S h a k e s p e a r e

(1564-1616)

T H E S O N N E T S

21

So is it not with me as with that muse,

Stirred by a painted beauty to his verse,

Who heaven it self for ornament doth use,

And every fair with his fair doth rehearse,

Making a couplement of proud compare

With sun and moon, with earth and sea’s rich gems:

With April’s first-born flowers and all things rare,

That heaven’s air in this huge rondure hems.

O let me true in love but truly write,

And then believe me, my love is as fair,

As any mother’s child, though not so bright

As those gold candles fixed in heaven’s air:

Let them say more that like of hearsay well,

I will not praise that purpose not to sell.

![]()

kempis poetry magazine

More in: -Shakespeare Sonnets

.jpg)

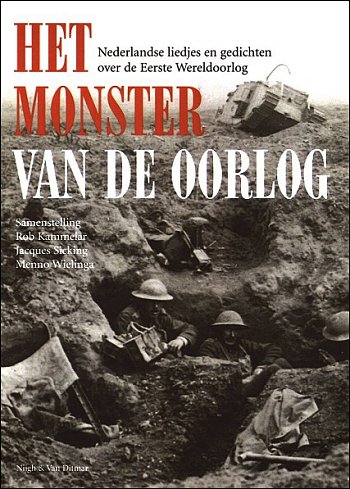

HET MONSTER VAN DE OORLOG

door Ed Schilders

De Eerste Wereldoorlog. Nederland bleef neutraal, wat zoveel betekende dat we niet in oorlog waren maar ‘gemobiliseerd’. Het is de tijd van miliciens, landweermannen, en rijwielbataljons die onze landsgrenzen bewaken. Ook toen al waren dat ‘onze jongens’. Onderschat ze niet. ‘Daar komen de jongens van Holland ’an’ is zowel de titel als de beginregel van een marslied, en de tweede regel rijmt daarop met ‘De grond en de huizen, ze trillen er van’. Het eindigt zo: ‘Zij vechten niet graag, maar alleen als het moet,/ Dan slaan zij er op, en dan vechten zij goed.’ De samenstellers van de bloemlezing Het monster van de oorlog hebben deze liedtekst opgenomen als een voorbeeld van ‘gezagsgetrouwe’ lyriek, en wel uit de in 1915 ‘op last van den Minister van Oorlog’ uitgegeven Zangbundel voor het Nederlandsche Leger.

Verreweg het overgrote deel van de bloemlezing valt gelukkig niet onder die departementale noemer van gezagsgetrouwheid. Mogen de gruwelen van Verdun en Ieper aan ons land voorbij zijn gegaan, de ‘Grote Oorlog’ was ook een tijd van armoede en werkloosheid, van broodkaarten en aardappelnood, van dienstweigeraars en in het gevang uitgeboet pacifisme. Er is vrijwel geen aspect van die in het nauw gebrachte samenleving of het is door dichter of cabaretier, door revue-artiest of straatzanger indertijd bezongen, en nu in Het monster van de oorlog gebloemleesd. De samenstellers hebben gekozen voor een brede interpretatie van ‘lyriek’, en hun bundel wordt daardoor wat de literaire kwaliteit aangaat onevenwichtig. Van J.C. Bloem tot de anonieme straatzanger. In het algemeen geldt voor deze verzameling echter: hoe dichter bij de straat, hoe indringender het uitzicht op het leven in gemobiliseerd Nederland. Want moest Gorter nou zo nodig geplukt worden voor deze ruiker? Of de ode aan de Franse maarschalk Joffre, een gedicht dat Marsman zelf al verdacht van ‘pathetiek’? Wij hebben nu eenmaal niet in de loopgraven liggen trillen. Wij hebben geen klassiekers als John McCrae en zijn klaprozen in Vlaanderen. Maar Nederland had wel honger en dienstweigeraars. We hadden Speenhoff (de Bob Hope van de landweermannen), Pisuisse, Charivarius, en Dirk Witte, wiens zwangere Jopie (uit ‘De peren’) helaas niet in de bloemlezing figureert, maar die keurig wordt vervangen door de meisjes in de Scheveningse duinen. Want ook daar kwamen de jongens. En vooral: de liedjes die op straat gezongen en verkocht werden door anoniem gebleven scharrelaars. Het is toch voornamelijk die alledaagsheid, het leven met aardappelnood, rats en kuch, en ‘per dag ’n kwart ons/ Vet van oude zilverbons’, die Het monster van de oorlog tot een bijzondere bloemlezing maakt.

Rob Kammelar e.a. (red.): Het monster van de oorlog – Nederlandse liedjes en gedichten over de Eerste Wereldoorlog – Nijgh & Van Ditmar – ISBN 90 388 0020 7

Eerder gepubliceerd in de Volkskrant

Ed Schilders: Het monster van de oorlog

k e m p i s p o e t r y m a g a z i n e

More in: Ed Schilders, POETRY ARCHIVE, WAR & PEACE

Jef van Kempen

Drie gedichten

Concept

Geen woord teveel

overdacht hij zijn daden,

ging stil voorbij

niet gezien en

niet gewogen.

Welk kind

werd niet verwekt

met de sombere schoonheid

van de dood voor ogen?

Suïcide

Het was geheel in overeenstemming met

wat zijn hart voelde maar wat zijn hoofd

vergat.

Omdat elk bewijs ontbrak, kreeg zijn onrust

geen warm onthaal, had hij als bron van kennis

en als gangmaker van valse praktijken afgedaan.

Zijn opvatting dat met het oog op de vooruitgang

geen genade kon worden verleend

(tenminste niet uit misplaatst medelijden)

dat in het licht van de resultaten van de samenspraak

van lichaam en ziel

een samenhang werd verondersteld

van gevoel en waarneming,

maakte zijn mistroostigheid alles onthullend,

waarbij de goede verstaander niet dient

te vergeten de invloed van gebrek aan slaap,

totdat hij als een schim fluisterend

zegde te zijn misleid en zich over te geven

aan een lichaam zonder een spoor van lust en

bandeloosheid, als een alledaagse omstandigheid

onherroepelijk hangend

aan het plafond

van zijn dromen.

My Lai

Het was een ongewone tijd.

Een goede lijkenscore

daar draaide het om,

daar werd niet stiekem

over gedaan.

Zo’n oorlog was het.

We sneden de oren af

van vrouwen en kinderen

en hingen die aan een ketting

om onze nek.

Zo’n oorlog was het.

Het was een ongewone tijd.

Jef van Kempen (1948) publiceerde poëzie, biografische artikelen, essays en literaire bloemlezingen. Daarnaast is hij actief als beeldend kunstenaar. Jef van Kempen is medeoprichter en redacteur van o.a. de poëziewebsite: KEMP=MAG – kempis poetry magazine ( www.kempis.nl ) en van de website Antony Kok Magazine ( www. antonykok.nl ) In 1966 publiceerde hij zijn eerste dichtbundel: Wiet. In 2010 verschijnt een verzamelbundel met gedichten en illustraties: Laatste bedrijf, gedichten 1963-2009 bij uitgeverij Art Brut, Postbus 117, 5120 AC Rijen, ISBN: 978-90-76326-04-7.

k e m p i s p o e t r y m a g a z i n e

More in: Kempen, Jef van

.jpg)

M u l t a t u l i

(Eduard Douwes Dekker, 1820-1887)

Saïdjah’s Zang

Ik weet niet waar ik sterven zal.

Ik heb de grote zee gezien aan de zuidkust,

toen ik daar was met mijn

vader om zout te maken.

Als ik sterf op de zee,

en men werpt mijn lichaam in het diepe water,

zullen er haaien komen.

Ze zullen rondzwemmen om mijn lijk,

en vragen: `Wie van ons zal het

lichaam verslinden dat daar daalt in het water?’

Ik zal ‘t niet horen.

Ik weet niet waar ik sterven zal.

Ik heb het huis zien branden van Pa-ansoe,

dat hij zelf had aangestoken omdat hij mataglap was.

Als ik sterf in een brandend huis,

zullen er gloeiende stukken hout

neervallen op mijn lijk.

En buiten het huis zal een groot geroep zijn

van mensen die water werpen om het vuur te doden.

Ik zal ‘t niet horen.

Ik weet niet waar ik sterven zal.

Ik heb de kleine Si-oenah zien vallen uit de klappa-boom,

toen hij een klappa plukte voor zijn moeder.

Als ik val uit een klappa-boom,

zal ik dood nederliggen aan de voet in

de struiken, als Si-oenah.

Dan zal mijn moeder niet schreien,

want zij is dood.

Maar anderen zullen roepen: `Zie,

daar ligt Saïdjah!’ met harde stem.

Ik zal ‘t niet horen.

Ik weet niet waar ik sterven zal.

Ik heb het lijk gezien van Pa-lisoe,

die gestorven was van hoge

ouderdom, want zijne haren waren wit.

Als ik sterf van ouderdom, met witte haren,

zullen de klaagvrouwen om mijn lijk staan.

En zij zullen misbaar maken als

de klaagvrouwen bij Pa-lisoe’s lijk.

En ook de kleinkinderen zullen schreien,

zeer luid.

Ik zal ‘t niet horen.

Ik weet niet waar ik sterven zal.

Ik heb velen gezien te Badoer,

die gestorven waren.

Men kleedde hen in een wit kleed,

en begroef hen in de grond.

Als ik sterf te Badoer,

en men begraaft mij buiten de dessa,

oostwaarts tegen de heuvel,

waar ‘t gras hoog is,

Dan zal Adinda daar voorbijgaan,

en de rand van haar sarong zal

zachtkens voortschuiven langs het gras…

Ik zal het horen.

.jpg)

Multatuli gedichten

kempis poetry magazine

V i r g i n i a W o o l f

(1882-1941)

Monday Or Tuesday

Lazy and indifferent, shaking space easily from his wings, knowing his way, the heron passes over the church beneath the sky. White and distant, absorbed in itself, endlessly the sky covers and uncovers, moves and remains. A lake? Blot the shores of it out! A mountain? Oh, perfect the sun gold on its slopes. Down that falls. Ferns then, or white feathers, for ever and ever.

Desiring truth, awaiting it, laboriously distilling a few words, for ever desiring (a cry starts to the left, another to the right. Wheels strike divergently. Omnibuses conglomerate in conflict) for ever desiring (the clock asseverates with twelve distinct strokes that it is mid-day; light sheds gold scales; children swarm) for ever desiring truth. Red is the dome; coins hang on the trees; smoke trails from the chimneys; bark, shout, cry “Iron for sale” and truth?

Radiating to a point men’s feet and women’s feet, black or gold-encrusted (This foggy weather. Sugar? No, thank you. The commonwealth of the future) the firelight darting and making the room red, save for the black figures and their bright eyes, while outside a van discharges, Miss Thingummy drinks tea at her desk, and plate-glass preserves fur coats.

Flaunted, leaf-light, drifting at corners, blown across the wheels, silver-splashed, home or not home, gathered, scattered, squandered in separate scales, swept up, down, torn, sunk, assembled and truth?

Now to recollect by the fireside on the white square of marble. From ivory depths words rising shed their blackness, blossom and penetrate. Fallen the book; in the flame, in the smoke, in the momentary sparks or now voyaging, the marble square pendant, minarets beneath and the Indian seas, while space rushes blue and stars glint truth? or now, content with closeness?

Lazy and indifferent the heron returns; the sky veils her stars; then bares them.

.jpg)

Virginia Woolf: Monday Or Tuesday

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Archive W-X, Woolf, Virginia

photo jefvankempen

Sara Bidaoui

Eerste Tilburgse Kinderstadsdichter

28 januari 2010

Sara Bidaoui (13) is de eerste kinderstadsdichter van Tilburg. Sara was één van de drie genomineerden kinderen voor deze nieuwe functie. De functie kinderstadsdichter was de hoofdprijs van een gedichtenwedstrijd met als onderwerp de stad Tilburg.

De wedstrijd was een initiatief van Stichting Cools, Cultuurconcepten.nl en de bibliotheek Midden-Brabant.

Sara won de wedstrijd met het gedicht: ‘Tilburg mijn stad, mijn thuis’. Ze mag haar functie bekleden tot augustus 2011. De tweede prijs ging naar Liz Abels en de derde prijs naar Lina van Bussel.

Tilburg: mijn stad, mijn thuis

Ik wil je zoveel vertellen

Je laten zien wat je mist

Maar het enige waar ik op kom is:

Mijn stad, mijn thuis

Ik wil je zoveel vertellen

Al is het maar op papier

Ik wil je laten zien

Mijn mooiste plekken hier

Maar het enige wat ik kan zeggen is:

Mijn stad, mijn thuis

Ik wil je zoveel vertellen

Maar ik weet niet hoe en wat

Woorden zat

Maar in mijn hoofd maar één gedachte:

Tilburg

Mijn stad, mijn thuis

Sara Bidaoui

![]()

Meer informatie op de website van Stichting Dr PJ Cools

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Bidaoui, Sara, City Poets / Stadsdichters, Kinderstadsdichters / Children City Poets

.jpg)

Wunsch, Indianer zu werden

Franz Kafka (1883-1924)

Wenn man doch ein Indianer wäre, gleich bereit, und auf dem rennenden Pferde, schief in der Luft, immer wieder kurz erzitterte über dem zitternden Boden, bis man die Sporen ließ, denn es gab keine Sporen, bis man die Zügel wegwarf, denn es gab keine Zügel, und kaum das Land vor sich als glatt gemähte Heide sah, schon ohne Pferdehals und Pferdekopf.

.jpg)

Franz Kafka: Betrachtung 1913 – Für M.B.

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive K-L, Franz Kafka, Kafka, Franz, Kafka, Franz

Gemeentemuseum Den Haag

Georges Vantongerloo

Voor een nieuwe wereld

23 januari 2010 t/m 16 mei 2010

Als een moderne Leonardo da Vinci concentreerde Georges Vantongerloo zich in zijn werk op de verhouding tussen het lichaam en de kosmos. In de kunstwereld wordt veel gerept van een synthese tussen kunst en leven, maar voor Vantongerloo waren dit geen loze woorden. Als voorvechter van een nieuwe wereld waarin zijn kunstzinnig gedachtegoed deel uit zou maken van ons dagelijks bestaan, bracht hij vele uren twijfelend, piekerend en worstelend door in zijn atelier en leverde tal van artistieke experimenten af die vaak passen in de palm van een hand! Begin 2010 wordt er in het Gemeentemuseum een groots retrospectief gewijd aan deze Belgische artistieke duizendpoot die zowel schilder, beeldhouwer, designer als projectontwikkelaar was.

Vantongerloo maakte maar kortstondig deel uit van De Stijl, maar zijn contact met Piet Mondriaan was blijvend. Hoewel bekend was dat Piet Mondriaan intuïtief werkte, was Vantongerloo ervan overtuigd dat er een wiskundige code ten grondslag lag zijn composities. Met papieren vol eindeloze berekeningen probeerde hij de ‘code van Mondriaan’ te kraken, zonder een éénduidige uitkomst.

Autonome beeldhouw- en schilderkunst, maar ook ontwerpen voor koffieservies, meubelen, vliegvelden, bruggen en andere infrastructuur kwamen van de hand van Vantongerloo. Als utopisch denker vocht hij voor ‘zijn’ wereld, waarin zijn abstracte vormentaal ingeburgerd zou raken in de samenleving en zodoende zichtbaar in complete woonwijken met tramlijnen, straten, straatverlichting en stratennamen. Hoe inventief hij ook was in zijn ontwerpen, Vantongerloo was nu eenmaal geen ingenieur en zijn infrastructurele ontwerpen bleven, ondanks zijn grote lobby gedurende zijn woonperiode in Parijs, altijd onuitgevoerd.

De kracht, maar misschien ook wel de zwakte van Vantongerloo was, dat zijn oeuvre uitwaaiert over alle mogelijke kunstdisciplines, waardoor hij zich nooit definitief heeft verbonden aan één belangrijk statement of succes. Hij offerde zich op aan zijn artistieke ideeën, maar miste net het raffinement om er ook succesvol mee te worden. Toch liet Vantongerloo diepe sporen na in de kunstgeschiedenis, als medewerker aan het tijdschrift De Stijl en als betrokkene bij de kunstenaarsgroep Abstraction-Création in Parijs.

Als mede-grondlegger van de geometrische abstractie en het constructivisme is Vantongerloo onterecht in de vergetelheid geraakt. Het Gemeentemuseum Den Haag en het Lehmbruck museum in Duisburg hebben daarom de handen ineengeslagen voor een overzichtstentoonstelling van Vantongerloo én tijdgenoten als Max Bill en Piet Mondriaan. Eigenlijk had deze tentoonstelling niet georganiseerd mogen worden, Vantongerloo had namelijk in zijn testament laten vastleggen dat er nooit een tentoonstelling van hem in Nederland zou mogen komen.

Bij de tentoonstelling verschijnt een kleurrijke monografie met bijdragen van met bijdragen van Marion Bornscheuer, Christoph Brockhaus, Hans Janssen, Angela Thomas Schmid, Francisca Vandepitte en Marek Wieczorek (€ 44,50)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: De Stijl

Luigi Pirandello

(1867-1936)

W a r

The passengers who had left Rome by the night express had had to stop until dawn at the small station of Fabriano in order to continue their journey by the small old-fashioned local joining the main line with Sulmona.

At dawn, in a stuffy and smoky second-class carriage in which five people had already spent the night, a bulky woman in deep mourning was hosted in—almost like a shapeless bundle. Behind her—puffing and moaning, followed her husband—a tiny man; thin and weakly, his face death-white, his eyes small and bright and looking shy and uneasy.

Having at last taken a seat he politely thanked the passengers who had helped his wife and who had made room for her; then he turned round to the woman trying to pull down the collar of her coat and politely inquired:

“Are you all right, dear?”

The wife, instead of answering, pulled up her collar again to her eyes, so as to hide her face.

“Nasty world,” muttered the husband with a sad smile.

And he felt it his duty to explain to his traveling companions that the poor woman was to be pitied for the war was taking away from her her only son, a boy of twenty to whom both had devoted their entire life, even breaking up their home at Sulmona to follow him to Rome, where he had to go as a student, then allowing him to volunteer for war with an assurance, however, that at least six months he would not be sent to the front and now, all of a sudden, receiving a wire saying that he was due to leave in three days’ time and asking them to go and see him off.

The woman under the big coat was twisting and wriggling, at times growling like a wild animal, feeling certain that all those explanations would not have aroused even a shadow of sympathy from those people who—most likely—were in the same plight as herself. One of them, who had been listening with particular attention, said:

“You should thank God that your son is only leaving now for the front. Mine has been sent there the first day of the war. He has already come back twice wounded and been sent back again to the front.”

“What about me? I have two sons and three nephews at the front,” said another passenger.

“Maybe, but in our case it is our only son,” ventured the husband.

“What difference can it make? You may spoil your only son by excessive attentions, but you cannot love him more than you would all your other children if you had any. Parental love is not like bread that can be broken to pieces and split amongst the children in equal shares. A father gives all his love to each one of his children without discrimination, whether it be one or ten, and if I am suffering now for my two sons, I am not suffering half for each of them but double…”

“True…true…” sighed the embarrassed husband, “but suppose (of course we all hope it will never be your case) a father has two sons at the front and he loses one of them, there is still one left to console him…while…”

“Yes,” answered the other, getting cross, “a son left to console him but also a son left for whom he must survive, while in the case of the father of an only son if the son dies the father can die too and put an end to his distress. Which of the two positions is worse? Don’t you see how my case would be worse than yours?”

“Nonsense,” interrupted another traveler, a fat, red-faced man with bloodshot eyes of the palest gray.

He was panting. From his bulging eyes seemed to spurt inner violence of an uncontrolled vitality which his weakened body could hardly contain.

“Nonsense, “he repeated, trying to cover his mouth with his hand so as to hide the two missing front teeth. “Nonsense. Do we give life to our own children for our own benefit?”

The other travelers stared at him in distress. The one who had had his son at the front since the first day of the war sighed: “You are right. Our children do not belong to us, they belong to the country…”

“Bosh,” retorted the fat traveler. “Do we think of the country when we give life to our children? Our sons are born because…well, because they must be born and when they come to life they take our own life with them. This is the truth. We belong to them but they never belong to us. And when they reach twenty they are exactly what we were at their age. We too had a father and mother, but there were so many other things as well…girls, cigarettes, illusions, new ties…and the Country, of course, whose call we would have answered—when we were twenty—even if father and mother had said no. Now, at our age, the love of our Country is still great, of course, but stronger than it is the love of our children. Is there any one of us here who wouldn’t gladly take his son’s place at the front if he could?”

There was a silence all round, everybody nodding as to approve.

“Why then,” continued the fat man, “should we consider the feelings of our children when they are twenty? Isn’t it natural that at their age they should consider the love for their Country (I am speaking of decent boys, of course) even greater than the love for us? Isn’t it natural that it should be so, as after all they must look upon us as upon old boys who cannot move any more and must sit at home? If Country is a natural necessity like bread of which each of us must eat in order not to die of hunger, somebody must go to defend it. And our sons go, when they are twenty, and they don’t want tears, because if they die, they die inflamed and happy (I am speaking, of course, of decent boys). Now, if one dies young and happy, without having the ugly sides of life, the boredom of it, the pettiness, the bitterness of disillusion…what more can we ask for him? Everyone should stop crying; everyone should laugh, as I do…or at least thank God—as I do—because my son, before dying, sent me a message saying that he was dying satisfied at having ended his life in the best way he could have wished. That is why, as you see, I do not even wear mourning…”

He shook his light fawn coat as to show it; his livid lip over his missing teeth was trembling, his eyes were watery and motionless, and soon after he ended with a shrill laugh which might well have been a sob.

“Quite so…quite so…” agreed the others.

The woman who, bundled in a corner under her coat, had been sitting and listening had—for the last three months—tried to find in the words of her husband and her friends something to console her in her deep sorrow, something that might show her how a mother should resign herself to send her son not even to death but to a probable danger of life. Yet not a word had she found amongst the many that had been said…and her grief had been greater in seeing that nobody—as she thought—could share her feelings.

But now the words of the traveler amazed and almost stunned her. She suddenly realized that it wasn’t the others who were wrong and could not understand her but herself who could not rise up to the same height of those fathers and mothers willing to resign themselves, without crying, not only to the departure of their sons but even to their death.

She lifted her head, she bent over from her corner trying to listen with great attention to the details which the fat man was giving to his companions about the way his son had fallen as a hero, for his King and his Country, happy and without regrets. It seemed to her that she had stumbled into a world she had never dreamt of, a world so far unknown to her, and she was so pleased to hear everyone joining in congratulating that brave father who could so stoically speak of his child’s death.

Then suddenly, just as if she had heard nothing of what had been said and almost as if waking up from a dream, she turned to the old man, asking him:

“Then…is your son really dead?”

Everyone stared at her. The old man, too, turned to look at her, fixing his great, bulging, horribly watery light gray eyes, deep in her face. For some time he tried to answer, but words failed him. He looked and looked at her, almost as if only then—at that silly, incongruous question—he had suddenly realized at last that his son was really dead—gone for ever—for ever. His face contracted, became horribly distorted, then he snatched in haste a handkerchief from his pocket and, to the amazement of everyone, broke into harrowing, heart-breaking, uncontrollable sobs.

Luigi Pirandello: War

kempis poetry magazine

More in: Archive O-P, Luigi Pirandello

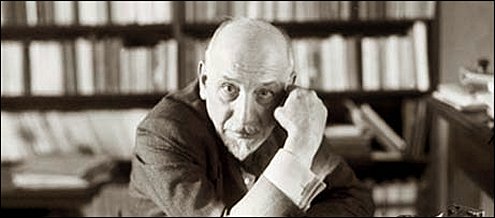

.jpg)

Guy de Maupassant

(1850-1893)

Le Mur

Les fenêtres étaient ouvertes. Le salon

Illuminé jetait des lueurs d’incendies,

Et de grandes clartés couraient sur le gazon.

Le parc, là-bas, semblait répondre aux mélodies

De l’orchestre, et faisait une rumeur au loin.

Tout chargé des senteurs des feuilles et du foin,

L’air tiède de la nuit, comme une molle haleine,

S’en venait caresser les épaules, mêlant

Les émanations des bois et de la plaine

À celles de la chair parfumée, et troublant

D’une oscillation la flamme des bougies.

On respirait les fleurs des champs et des cheveux.

Quelquefois, traversant les ombres élargies,

Un souffle froid, tombé du ciel criblé de feux,

Apportait jusqu’à nous comme une odeur d’étoiles.

Les femmes regardaient, assises mollement,

Muettes, l’oeil noyé, de moment en moment

Les rideaux se gonfler ainsi que font des voiles,

Et rêvaient d’un départ à travers ce ciel d’or,

Par ce grand océan d’astres. Une tendresse

Douce les oppressait, comme un besoin plus fort

D’aimer, de dire, avec une voix qui caresse,

Tous ces vagues secrets qu’un coeur peut enfermer.

La musique chantait et semblait parfumée;

La nuit embaumant l’air en paraissait rythmée,

Et l’on croyait entendre au loin les cerfs bramer.

Mais un frisson passa parmi les robes blanches;

Chacun quitta sa place et l’orchestre se tut,

Car derrière un bois noir, sur un coteau pointu,

On voyait s’élever, comme un feu dans les branches,

La lune énorme et rouge à travers les sapins.

Et puis elle surgit au faîte, toute ronde,

Et monta, solitaire, au fond des cieux lointains,

Comme une face pâle errant autour du monde.

Chacun se dispersa par les chemins ombreux

Où, sur le sable blond, ainsi qu’une eau dormante,

La lune clairsemait sa lumière charmante.

La nuit douce rendait les hommes amoureux,

Au fond de leurs regards allumant une flamme.

Et les femmes allaient, graves, le front penché,

Ayant toutes un peu de clair de lune à l’âme.

Les brises charriaient des langueurs de péché.

J’errais, et sans savoir pourquoi, le coeur en fête.

Un petit rire aigu me fit tourner la tête,

Et j’aperçus soudain la dame que j’aimais,

Hélas! d’une façon discrète, car jamais

Elle n’avait cessé d’être à mes voeux rebelle:

« Votre bras, et faisons un tour de parc », dit-elle.

Elle était gaie et folle et se moquait de tout,

Prétendait que la lune avait l’air d’une veuve:

« Le chemin est trop long pour aller jusqu’au bout,

Car j’ai des souliers fins et ma toilette est neuve;

Retournons. » Je lui pris le bras et l’entraînai.

Alors elle courut, vagabonde et fantasque,

Et le vent de sa robe, au hasard promené,

Troublait l’air endormi d’un souffle de bourrasque.

Puis elle s’arrêta, soufflant; et doucement

Nous marchâmes sans bruit tout le long d’une allée.

Des voix basses parlaient dans la nuit, tendrement,

Et, parmi les rumeurs dont l’ombre était peuplée,

On distinguait parfois comme un son de baiser.

Alors elle jetait au ciel une roulade!

Vite tout se taisait. On entendait passer

Une fuite rapide; et quelque amant maussade

Et resté seul pestait contre les indiscrets.

Un rossignol chantait dans un arbre, tout près,

Et dans la plaine, au loin, répondait une caille.

Soudain, blessant les yeux par son reflet brutal,

Se dressa, toute blanche, une haute muraille,

Ainsi que dans un conte un palais de métal.

Elle semblait guetter de loin notre passage.

« La lumière est propice à qui veut rester sage,

Me dit-elle. Les bois sont trop sombres, la nuit.

Asseyons-nous un peu devant ce mur qui luit. »

Elle s’assit, riant de me voir la maudire.

Au fond du ciel, la lune aussi me sembla rire!

Et toutes deux d’accord, je ne sais trop pourquoi,

Paraissaient s’apprêter à se moquer de moi.

Donc, nous étions assis devant le grand mur blême;

Et moi, je n’osais pas lui dire: « Je vous aime! »

Mais comme j’étouffais, je lui pris les deux mains.

Elle eut un pli léger de sa lèvre coquette

Et me laissa venir comme un chasseur qui guette.

Des robes, qui passaient au fond des noirs chemins,

Mettaient parfois dans l’ombre une blancheur douteuse.

La lune nous couvrait de ses rayons pâlis

Et, nous enveloppant de sa clarté laiteuse,

Faisait fondre nos coeurs à sa vue amollis.

Elle glissait très haut, très placide et très lente,

Et pénétrait nos chairs d’une langueur troublante.

J’épiais ma compagne, et je sentais grandir

Dans mon être crispé, dans mes sens, dans mon âme,

Cet étrange tourment où nous jette une femme

Lorsque fermente en nous la fièvre du désir!

Lorsqu’on a, chaque nuit, dans le trouble du rêve,

Le baiser qui consent, le « oui » d’un oeil fermé,

L’adorable inconnu des robes qu’on soulève,

Le corps qui s’abandonne, immobile et pâmé,

Et qu’en réalité la dame ne nous laisse

Que l’espoir de surprendre un moment de faiblesse!

Ma gorge était aride; et des frissons ardents

Me vinrent, qui faisaient s’entrechoquer mes dents,

Une fureur d’esclave en révolte, et la joie

De ma force pouvant saisir, comme une proie,

Cette femme orgueilleuse et calme, dont soudain

Je ferais sangloter le tranquille dédain!

Elle riait, moqueuse, effrontément jolie;

Son haleine faisait une fine vapeur

Dont j’avais soif. Mon coeur bondit; une folie

Me prit. Je la saisis en mes bras. Elle eut peur,

Se leva. J’enlaçai sa taille avec colère,

Et je baisai, ployant sous moi son corps nerveux,

Son oeil, son front, sa bouche humide et ses cheveux!

La lune, triomphant, brillait de gaieté claire.

Déjà je la prenais, impétueux et fort,

Quand je fus repoussé par un suprême effort.

Alors recommença notre lutte éperdue

Près du mur qui semblait une toile tendue.

Or, dans un brusque élan nous étant retournés,

Nous vîmes un spectacle étonnant et comique.

Traçant dans la clarté deux corps désordonnés,

Nos ombres agitaient une étrange mimique,

S’attirant, s’éloignant, s’étreignant tour à tour.

Elles semblaient jouer quelque bouffonnerie,

Avec des gestes fous de pantins en furie,

Esquissant drôlement la charge de l’Amour.

Elles se tortillaient farces ou convulsives,

Se heurtaient de la tête ainsi que des béliers;

Puis, redressant soudain leurs tailles excessives,

Restaient fixes, debout comme deux grands piliers.

Quelquefois, déployant quatre bras gigantesques,

Elles se repoussaient, noires sur le mur blanc,

Et, prises tout à coup de tendresses grotesques,

Paraissaient se pâmer dans un baiser brûlant.

La chose étant très gaie et très inattendue,

Elle se mit à rire. – Et comment se fâcher,

Se débattre et défendre aux lèvres d’approcher

Lorsqu’on rit? Un instant de gravité perdue

Plus qu’un coeur embrasé peut sauver un amant!

Le rossignol chantait dans son arbre. La lune

Du fond du ciel serein recherchait vainement

Nos deux ombres au mur et n’en voyait plus qu’une.

Guy de Maupassant poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive M-N, Archive M-N, Guy de Maupassant, Maupassant, Guy de

.jpg)

William Butler Yeats

(1865-1939)

Mad As The Mist And Snow

Bolt and bar the shutter,

For the foul winds blow:

Our minds are at their best this night,

And I seem to know

That everything outside us is

Mad as the mist and snow.

Horace there by Homer stands,

Plato stands below,

And here is Tully’s open page.

How many years ago

Were you and I unlettered lads

Mad as the mist and snow?

You ask what makes me sigh, old friend,

What makes me shudder so?

I shudder and I sigh to think

That even Cicero

And many-minded Homer were

Mad as the mist and snow.

Winter (2) 2010

Photos: Ton van Kempen

Poem: W.B. Yeats

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: 4SEASONS#Winter, Dutch Landscapes, Ton van Kempen Photos, Yeats, William Butler

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature