Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Charles Cros

(1842 – 1888)

Six tercets

A Degas

Les cheveux plantureux et blonds, bourrés de crin.

Se redressent altiers : deux touffes latérales

Se collent sur le front en moqueuses spirales.

Aigues-marines. dans le transparent écrin

Des paupières, les yeux qu’un clair fluide baigne

Ont un voluptueux regard qui me dédaigne.

Tout me nargue : les fins sourcils, arcs indomptés.

Le nez”au flair savant, la langue purpurine

Oui s’allonge jusqu’à chatouiller la narine.

Et le menton pointu, signe des volontés

Implacables, et puis cette irritante mouche

Sise au-dessous du nez et tout près de la bouche.

Mais, au bout du menton rose où vient se poser

In doigt mignon, dans cette attitude songeuse,

Énigmatiquement la fossette se creuse.

Je prends, à la faveur de ce calme, un baiser

Sur les flocons dont la nuque fine est couverte,

En prix de ce croquis rimé d’après vous,

Berthe.

Charles Cros poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive C-D, Cros, Charles

Ivo van Leeuwen: Nationale waardenpapierverbranding. Brand los voor eer en geweten.

fleursdumal.nl digital magazine

More in: Exhibition Archive, Illustrators, Illustration, Ivo van Leeuwen

Het mooiste internationale literatuurfestival van Nederland | donderdag 14 t/m zondag 17 januari 2016 in Den Haag

Het mooiste internationale literatuurfestival van Nederland | donderdag 14 t/m zondag 17 januari 2016 in Den Haag

Winternachten Festival van donderdag 14 t/m zondag 17 januari 2016 in Den Haag

Het Winternachten Festival neemt in januari 2016 vier dagen lang bezit van de podia van Theater aan het Spui en Filmhuis Den Haag. Hieronder het programma met tijden en toegangsprijzen.

De kaartverkoop is van start gegaan – met vroegboekkorting op tickets voor de grote festivalavonden op vrijdag 15 en zaterdag 16 januari.

Te gast zijn:

ADONIS | TARIQ ALI | JOSÉ EDUARDO AGUALUSA | ALAA AL ASWANI |JOANNA BATOR | ABDELKADER BENALI | WIM BRANDS | MIRCEA CARTARESCU | JUNG CHANG | JENNIFER CLEMENT | ADRIAAN VAN DIS | RENATE DORRESTEIN | GYÖRGI DRAGOMÁN | SLAVENKA DRAKULIĆ | MIRA FETICU | RODAAN AL GALIDI | PETINA GAPPAH | DAAN HEERMA VAN VOSS | KRISTIEN HEMMERECHTS | TOINE HEIJMANS | STINE JENSEN | KARL OVE KNAUSGÅRD | HERMAN KOCH | ANDREJ KOERKOV | MICHEL KRIELAARS | MICHAEL KRÜGER | GEERT MAK | NEEL MUKHERJEE | SUSAN NEIMAN | JAMAL OUARIACHI | CONNIE PALMEN | ILJA LEONARD PFEIFFER | JEROEN VAN ROOIJ | INGE SCHILPEROORD | RUNA SVETLIKOVA | P.F. THOMÉSE | MAUD VANHAUWAERT | ANNELIES VERBEKE | ANNA WOLTZ e.v.a.

Muziek:

GUY DANEL | DJ SOCRATES | DICK VAN DER HARST | HELMUT LOTTI | GERSON MAIN | WIM SEGERS | TYPHOON | FLOREJAN VERSCHUEREN | REINIER VOET | LIESELOT DE WILDE |

FESTIVALPROGRAMMA

donderdag 14 januari vanaf 20:00 uur (€ 15/ UITpas € 12,50/CJP, studenten, Ooievaarspas € 7,50)

OPENING NIGHT de vrijheid van meningsuiting staat centraal op deze avond, met de Free the Word!-speech door Jung Chang (Wilde Zwanen) en de uitreiking van de Oxfam Novib PEN Award for Freedom of Expression

vrijdag 15 januari vanaf 20:00 uur (€ 28,50/€ 26/€ 14,25)*

FRIDAY NIGHT UNLIMITED grote gevarieerde festivalavond met tientallen programma’s met heel veel schrijvers. Met één ticket toegang tot alle programma-onderdelen, muziekoptredens en festivalfilms

zaterdag 16 januari 14:30-15:45 (€ 15/€ 12,50/€ 7,50)**

zaterdag 16 januari 14:30-15:45 (€ 15/€ 12,50/€ 7,50)**

WIM BRANDS INTERVIEWT KARL OVE KNAUSGÅRD

zaterdag 16 januari 16:15-17:30 (€ 15/€ 12,50/€ 7,50)**

LEESCLUB WIM BRANDS over Vrouw, het 6de deel van de serie Mijn Strijd van Karl Ove Knausgård

zaterdag 16 januari 14:30-15:45 (€ 15/€ 12,50/€ 7,50)**

NRC LEESCLUB LIVE over Lucifer van Connie Palmen

zaterdag 16 januari 16:15-17:30 (€ 15/€ 12,50/€ 7,50)**

ANNA LUYTEN INTERVIEWT CONNIE PALMEN

zaterdag 16 januari vanaf 20:00 (€ 28,50/€ 26/€ 14,25)*

SATURDAY NIGHT UNLIMITED grote gevarieerde festivalavond met tientallen programma’s met heel veel schrijvers. Met één ticket toegang tot alle programma-onderdelen, muziekoptredens en festivalfilms

zondag 17 januari 10:00-11:30 (vrije toegang na aanmelding)

VPRO’s OVT LIVE vanuit de gezellige foyer van festivallocatie Theater aan het Spui: de radio-uitzending met publiek van dit populaire programma over de actualiteit van de geschiedenis

zondag 17 januari 14:00-16:00 (€ 15/€ 12,50/€ 7,50)

HET SCHRIJVERSFEEST de feestelijke afsluiting van het festival is een programma rond de Nederlandse literatuur en de uitreiking van de Jan Campert-prijzen, waaronder de Constantijn Huygens-prijs voor Adriaan van Dis voor zijn gehele oeuvre

# meer informatie op website writersunlimited/winternachten

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book Lovers, Art & Literature News, MUSIC, Renate Dorrestein, THEATRE, Winternachten

Hendrik Marsman

(1899-1940)

Sterfbed

Ik zie de zon nog in het venster staan

maar reeds vervaagt de schemering de uren.

Ik weet dat het niet lang meer duren kan,

totdat ik met den dood alleen zal zijn.

Gij hebt mij lief; ik heb vergeefs getracht

u zo volledig lief te hebben als gij mij;

vergeef het mij: ik heb het slecht gedaan,

en bid voor mij en ga dan van mij heen;

hoe teer en machtig het ook is geweest,

het heeft voor mij nu alles afgedaan.

Schrei niet, ik zal u nazien totdat gij

de deur volkomen achter u zult hebben afgesloten

en mij alleen gelaten met den dood;

ik heb een leven lang in lafheden verdaan, en groot

zal het ook in het eind niet zijn,

maar ik wil in het enige gevecht

dat er op aan komt, trachten geen knecht te zijn.

Kom, ga nu heen, slechts dan heb ik de kracht

dit laatste te doorstaan zoals gijzelf

dit laatste tussen u en mij doorstaat:

zonder veel tranen,

woordenloos en recht.

Hendrik Marsman poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive M-N, Marsman, Hendrik

Luise Büchner

(1821-1877)

Wenn der ein Dichter ist

Wenn der ein Dichter ist,

Dem, wenn der Mai erblühet,

Die Seele in der Brust

In Sehnsucht fast verglühet,

Der seine holde Pracht,

Den Jubel in den Hainen

Nur leis erwiedern kann

Mit schmerzlich süßem Weinen;

Wenn der ein Dichter ist,

Den Ehrfurcht tief durchbebet,

Wo schwindelnd groß vor ihm

Sich die Natur erhebet;

Dem fast der Athem stockt

Und wankt des Fußes Stärke,

Vor eines Genius

Erhab’nem Schöpferwerke;

Wenn der ein Dichter ist,

Dess’ Herz in Flammen lodert,

Wo Unterdrückung herrscht

Und Unbill Rechte fodert,

Dem nach der Feder zuckt

Die Hand, wie nach dem Schwerte,

Daß das Gemeine tief

Von ihm gezüchtigt werde;

Wenn der ein Dichter ist,

Den jede Menschenklage,

Den jedes fremde Leid

Trifft wie mit eignem Schlage,

Der keine Thräne sieht,

Die er nicht mit muß weinen,

Und dem der eigne Schmerz

Stets doppelt wird erscheinen;

Wenn der ein Dichter ist,

Dem heiß die Wange brennet,

Wenn man des Vaterlands

Geliebten Namen nennet,

Dem das entzückte Herz

In Wonne wollt’ vergehen,

Wenn einmal könnte noch

Er frei und groß es sehen!

Wenn der ein Dichter ist –

O, Gott – nicht kann ich spüren,

Ob ich in edler Form

Weiß fremdes Herz zu rühren,

Ob Geister mächt’gen Schwungs

Mein Geist empor kann raffen –

Doch meine Seele hast

Zum Dichter du geschaffen!

Luise Büchner poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, CLASSIC POETRY

![]() Hoofdstuk 9 – Inmiddels verstreek de middag. De zon was over zijn hoogste punt heen. De schaduwen begonnen langer te worden. Was vroeg in de middag het dorpsplein een en al zon, met alleen schaduw recht onder de meidoorn, nu was de schaduw overal.

Hoofdstuk 9 – Inmiddels verstreek de middag. De zon was over zijn hoogste punt heen. De schaduwen begonnen langer te worden. Was vroeg in de middag het dorpsplein een en al zon, met alleen schaduw recht onder de meidoorn, nu was de schaduw overal.

Voor opoe Ramesz was er in de buurt van haar huis geen plekje meer om in de zon te zitten. Haar gezicht stond dan ook erg ontevreden en ze zat te rillen van de kou. Jacob Ramesz, die het spelletje landverbeuren had verloren, maar dat goed kon verwerken omdat hij nooit op een overwinning had gerekend, liep naar zijn deurgat terug. Naar dat mens dat hem al jaren op zijn zenuwen werkte. Die klit aan zijn lijf. Dat zo iemand maar bleef leven. Vroeger, godverdomme, toen was het anders. Toen hoefde hij maar met zijn vingers te knippen om haar van de ene naar de andere hoek van zijn kot te laten kruipen. Dat mens hing daar maar in haar stoel. Levenloos, maar vast van plan het nog jaren vol te houden. Wat een ellende! Drie keer al had ze op het kantje gelegen. Drie keer had ze de genade der stervenden ontvangen, maar telkens had ze het overleefd. En alle keren was ze met veel zorg door kerk en buurt omgeven geweest. Terwijl ze zich anders nooit iets van haar aantrokken, hadden de kraaien haar toen hartstikke verwend. Moest je toch eens horen hoe ze met haar poten op het stoofje zat te roffelen om hem te dwingen het ding bij te vullen. Gottegot, dat moest dan maar weer. Jacob deed zijn plicht. Als hij haar liet verrekken, zou het volk van Solde hem pas echt uitspuwen. Daar paste hij voor. Hij liet zich het dorp niet uit jagen. Hij dook in het achterhuis om de laatste kolen bij elkaar te schrapen. Er was nog brandstof voor een paar dagen. Dan zou ze het zonder moeten doen.

Hij was benieuwd hoe ze daarop zou reageren. Zou ze gaan schreeuwen? Hysterisch worden? Zo zat opoe Ramesz even later weer boven haar rokende stoofje te glimlachen. De walm trok onder haar rokken en kroop tussen kraag en mouwen naar buiten. Ze was er zo aan gewend geraakt dat ze er niet eens meer van hoefde te hoesten. Ze hoorde de timmerman maar zag hem niet, omdat haar hersens de beelden die haar ogen opvingen door de molen haalden. De omgeving voor haar veranderend in steeds andere, maar steeds verkeerd in elkaar gezette legpuzzels. Waarin zelfs zij, opoe Ramesz zelf, met haar eigen stoofje, dan weer hier, dan weer daar zat. In de meidoorn of op de tafel van de kaarters. Tegen de gevel van de kerk of onder het bed van de jongen. Soms broederlijk naast de tamme buizerd of tot aan haar strot in de spoelbak. Nooit voor haar deur. Ze zat er met haar rug naartoe, zodat haar eigen huis en haar eigen vent nooit in het verwarde legpatroon van haar waarnemingen voorkwamen. Haar warme stoofje maakte haar weer zo opgewekt dat ze naar iedereen leek te lachen.

Ondertussen had de timmerman, zo goed en zo kwaad als hij kon, het gat in het dak van de kerk gedicht. Hij ging naar binnen om de pastoor aan te spreken over het resterende deel van zijn loon, maar Joachim Andrade gaf niet thuis. In extase lag hij op de trappen voor het altaar te bidden. Iedereen in Solde wist dat je hem in deze houding niet mocht storen, omdat zijn hemelse verrukking dan binnen één tel kon omslaan in aardse gramschap. Wel vreemd dat men hem altijd aantrof in gebed als men iets van hem nodig had. Als het op geld aankwam, had die pastoor altijd wel wat om een mens aan het lijntje te houden. De timmerman vloekte, maar begreep dat er op dit moment geen cent voor hem in het vat zat. Hij zwoer nooit meer een hand voor die verdomde zwartrok uit te steken. Teleurgesteld verzamelde hij zijn gereedschap, nam zijn ladder op de nek en sjouwde terug naar de werkplaats. Hij zette de ladder binnen en plofte als een zak in een hoop houtkrullen. Hij snakte naar drank, maar hij was zo moe als een hond en bleef van louter ellende liggen. Nu het tegen de avond liep, leek het of alle geluiden wat dichter in elkaar schoven. Het geratel van de bakkerskar die het plein op reed, klonk dan ook des te harder op. Het knarsen van de wielen over het grind drong scherp in alle hoeken door.

Ton van Reen: Landverbeuren (56)

wordt vervolgd

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Landverbeuren, Reen, Ton van

Hans Christian Andersen: ‘Beautiful’

Alfred the sculptor – yes, you know him, don’t you? We all know him; he was awarded the gold medal, traveled to Italy, and came home again. He was young then; in fact, he is still young, though he is ten years older than he was at that time.

After he returned home, he visited one of the little provincial towns on the island of Zealand. The whole village knew who the stranger was, and in his honor one of the richest families gave a party. Everyone of any importance or owning any property was invited. It was quite an event, and all the village knew about it without its being announced by the town crier. Apprentice boys and the children of poor people, and even some of their parents, stood outside the house, looking at the lighted windows with their drawn curtains; and the watchman could imagine that he was giving the party, there were so many people in his street. There was an air of festivity everywhere, and inside the house, too, for Mr. Alfred the sculptor was there.

He talked and told stories, and everybody listened to him with pleasure and enthusiasm, but none more so than the elderly widow of a state official. As far as Mr. Alfred was concerned, she was like a blank sheet of gray blotting paper, absorbing everything that was said and demanding more. She was highly susceptible and unbelievably ignorant-a sort of female Kaspar Hauser.

“I should love to see Rome!” she said. “It must be a wonderful city, with all the many strangers continually arriving there. Now, do tell us what Rome is like. How does the city look when you come in by the gate?”

“It is not easy to describe it,” said the young sculptor. “There’s a great open place, and in the middle of it there is an obelisk that is four thousand years old.”

“An organist!” cried the lady, who had never heard the word “obelisk.”

Some of the guests could hardly keep from laughing, among them the sculptor, but the smile that rose to his lips quickly faded away, for he saw, close by the lady, a pair of dark-blue eyes; they belonged to the daughter of the lady who had been talking, and anyone with such a daughter could not really be silly! The mother was like a fountain of questions, and the daughter, who listened silently, might pass for the naiad of the fountain. How beautiful she was! She was something for a sculptor to look at, but not to speak with, for indeed she talked but very little.

“Has the Pope a large family?” asked the lady.

And the young man answered considerately, as if the question had been put differently, “No, he doesn’t come of a very great family.”

“That’s not what I mean,” said the lady. “I mean, does he have a wife and children?”

“The Pope isn’t allowed to marry,” he replied.

“I don’t approve of that,” said the lady.

She might well have talked and questioned him more intelligently, but if she hadn’t said and asked what she did, would her daughter have leaned so gracefully on her shoulder, looking straight before her with an almost melancholy smile on her lips?

And Mr. Alfred told them of the glorious colors of Italy, the purple of the mountains, the blue of the Mediterranean, the blue of the southern skies, a beauty that could only be surpassed in the North by the deep-blue eyes of a maiden. This he said with peculiar meaning, but she who should have understood it looked quite unconscious, and that, too, was charming!

“Ah, Italy!” sighed some of the guests.

“Traveling!” sighed others.

“Charming, charming!”

“Well,” said the widow, “if I win fifty thousand dollars in the lottery, we’ll travel! My daughter and I. You Mr. Alfred, must be our guide. We’ll all three go, with just one or two good friends with us.” Then she smiled in such a friendly manner at the company that each of them could imagine he was the person who would accompany them to Italy. “Yes, we’ll go to Italy! But not to the parts where the robbers are; we’ll stay in Rome and only travel by the great highways where we’ll be safe.”

And the daughter sighed very gently. And how much may lie in one little sigh or be read into it! The young man read a great deal into it. Those two blue eyes, bright that evening in his honor, must conceal treasures of heart and mind rarer than all the glories of Rome! When he left the party, he had lost his heart-lost it completely-to the young lady.

Now, the widow’s house was where Mr. Alfred the sculptor could most frequently be found. It was understood that his calls were not for the lady herself, though he and she did all the talking; he really came for the sake of the daughter. They called her Kala. Her real name was Karen Malene, but the two names had been contracted into the single name Kala. She was extremely, but some people said she was rather dull and probably slept late in the mornings.

“She has been accustomed to that since childhood,” said her mother. “She is as beautiful as Venus, and a beauty always tires easily. She does sleep rather late, but that’s what makes her eyes so bright.”

What a power there was in these clear eyes, these deep blue eyes! “Still waters run deep.” The young man felt the truth of that proverb, and his heart sank into the depths. He spoke of his adventures, and Mamma always asked the same naïve and pertinent questions she had asked at their first meeting.

It was a delight to hear Mr. Alfred speak. He told them of Naples, of trips to Mount Vesuvius, and showed them colored prints of some of the eruptions. The widow had never heard of such things before, much less taken time to think about them.

“Mercy save us!” she said. “So that’s a burning mountain! But isn’t it dangerous for the people who live there?”

“Entire cities have been destroyed,” he answered. “For example, Pompeii and Herculaneum.”

“Oh, the poor people! And you saw all that yourself?”

“Well, no, I didn’t see any of the eruptions shown in these pictures, but I’ll show you a drawing I made of an eruption I did see.”

He laid a pencil sketch on the table, and when Mamma, who had been studying the highly colored prints, glanced at the black-and-white drawing, she cried in amazement, “When you saw it did it throw up white fire?”

For a moment Alfred’s respect for Kala’s mamma nearly vanished; but then, dazzled by the light from Kala, he decided it was natural for the old lady to have no eye for color. After all, it didn’t matter, for Kala’s mamma had the most wonderful thing of all-she had Kala herself.

And Alfred and Kala were engaged, which was inevitable, and the engagement was announced in the town newspaper. Mamma brought thirty copies of the paper, so she could cut out the announcement and send it to her friends. The betrothed couple were happy, and the mamma-in-law-to-be was happy, too; she said it seemed like being related to Thorvaldsen himself.

“At any rate, you are his successor,” she told Alfred.

And it seemed to Alfred that Mamma had this time really said something clever. Kala said nothing, but her eyes sparkled; her every gesture was graceful. Yes, she was beautiful; that cannot be repeated too often.

Alfred made busts of Kala and his future mamma-in-law; they sat for him and watched how he molded and smoothed the soft clay between his fingers.

“I suppose it’s only for us that you do this common work,” said Mamma-in-law-to-be, “and don’t have your servant do all that dabbing together.”

“No, I have to mold the clay myself,” he explained.

“Oh, yes, you’re always so exceedingly polite,” said Mamma, while Kala silently pressed his hand, still soiled by the clay.

Then he unfolded to both of them the loveliness of nature in creation, explaining how the living stood higher in the scale than the dead, how the plant was above the mineral, the animal above the plant, and man above the animal, how mind and beauty are united in outward form, and how it was the task of the sculptor to seize that beauty and imprison it in his works.

Kala sat silent and nodded approval of the thought, while Mamma-in-law confessed, “It’s hard to follow all that. But my thoughts manage to hobble slowly along after you; they whirl around, but I try to hold them fast.”

And the power of Kala’s beauty held Alfred fast, seizing him and mastering him and filling his whole soul. There was beauty in Kala’s every feature; it sparkled in her eyes, lurked in the corners of her mouth and even in each movement of her fingers. The sculptor saw this; he spoke only of her, thought only of her, until the two became one. Thus it might be said that she also spoke often, for he was always talking of her, and they two were one.

Such was the betrothal; and now came the wedding day, with bridesmaids and presents, all duly mentioned in the wedding speech.

Mamma-in-law had set up a bust of Thorvaldsen, attired in a dressing gown, at one end of the table, for it was her whim that he was to be a guest. There were songs and toasts, for it was a gay wedding and they were a handsome pair. “Pygmalion gets his Galatea,” one of the songs said.

“That is something from mythology!” said Mamma-in-law.

Next day the young couple left for Copenhagen, where they were to live. Mamma-in-law went with them, “to give them a helping hand,” she explained-which meant to take charge of the house. Kala was to live in a doll’s house. Everything was so bright, new, and fine. There the three of them sat, and as for Alfred, to use a proverb that describes his circumstances, he sat like the bishop in the goose yard.

The magic of form had fascinated him. He had regarded the case and had no interest in learning what the case contained, and that is unfortunate, very unfortunate, in married life! If the case breaks and the gilding rubs off, the purchaser may repent of his bargain. It is very embarrassing to discover in a large party that one’s suspender buttons are coming off and that one has no belt to fall back on; but it is still worse to realize at a great party that one’s wife and mother-in-law are talking nonsense and that one cannot think of a clever piece of wit to cover up the stupidity of it.

The young couple often sat hand in hand, he speaking and she letting drop a word now and then-with always the same melody, like a clock striking the same two or three notes constantly. It was really a mental relief when one of her friends, Sophie, came to visit them.

Sophie wasn’t pretty. To be sure, she was not deformed; Kala always said she was a little crooked, but no one but a female friend would have noticed that. She was a very levelheaded girl and had no idea that she might ever become dangerous here. Her visits brought a fresh breath of air into the doll’s house, air that they all agreed was certainly needed there. But they felt they needed more airing, so they came out into the air, and Mamma-in-law and the young couple traveled to Italy.

“Thank heaven we are back in our own home again!” said both mother and daughter when they and Alfred returned home a year later.

“Traveling is no fun,” said Mamma-in-law. “On the contrary, it’s very tiring; pardon me for saying so. I found the time dragged, even though I had my children with me; and it is expensive, very expensive, to travel. All those galleries you have to see, and all the things you have to look at! You must do it for self-protection, because when you get back people are sure to ask you about them; and then they’re sure to tell you that you’ve missed the most worth-while things. I got so tired at last of those everlasting Madonnas; I thought I would turn into a Madonna myself!”

“And the food one gets!” said Kala.

“Yes,” agreed Mamma. “Not even a dish of honest meat soup! It is awful the way they cook!”

And Kala had become tired from traveling; she was always tired; that was the trouble. Sophie came to live with them, and her presence was a real help.

Mamma-in-law had to admit that Sophie understood both housekeeping and art, though you would hardly have expected a knowledge of the last from a person of her modest background. Moreover, she was honest and loyal; she showed that clearly when Kala lay sick, fading away.

If the case is everything, that case should be strong, or it is all over. And it was all over with the case-Kala died.

“She was so beautiful,” said Mamma. “She was very different from the antiques, because they’re all so damaged. Kala was completely perfect, just as a beauty should be.”

Alfred wept and the Mother wept, and both went into mourning. The black dresses became Mamma very well, so she wore her mourning the longer. Moreover, she soon experienced another grief, when she saw Alfred marry again. And he married Sophie, who had no looks at all!

“He has gone from one extreme to the other!” said Mamma-in-law. “Gone from the most beautiful to the ugliest! How could he forget his first wife! Men have no constancy. Now, my husband was entirely different, and he died before I did.”

“Pygmalion got his Galatea,” said Alfred. “Yes, that’s what the wedding song said. I really fell in love with a beautiful statue, which came to life in my arms, but the soul mate that heaven sends down to us, one of its angels who can comfort and sympathize with and uplift us, I have not found or won till now. You came to me, Sophie, not in the glory of superficial beauty – but fair enough, prettier than was necessary. The most important thing is still the most important. You came to teach a sculptor that his work is only clay and dust, only the outward form in a fabric that passes away, and that we must seek the spirit within. Poor Kala! Ours was but a wayfarer’s life. In the next world, where we shall come together through sympathy, we shall probably be half strangers to each other.

“That was not spoken kindly,” said Sophie, ” not like a true Christian. In the next world, where there is no marriage, but where, as you say, souls find each other through sympathy, where everything beautiful is developed and elevated, her soul may attain such completeness that it may resound far more melodiously than mine. Then you will again utter the first exciting cry of your love, ‘Beautiful, beautiful!'”

END

Hans Christian Andersen (1805—1875) fairy tales and stories

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Andersen, Andersen, Hans Christian, Archive A-B, Grimm, Andersen e.o.: Fables, Fairy Tales & Stories

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

(1749-1832)

Den Guten

Laßt euch einen Gott begeisten,

Euch beschränket nur mein Sagen.

Was ihr könnt, ihr werdet’s leisten,

Aber müßt mich nur nicht fragen.

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive G-H, Goethe, Johann Wolfgang von

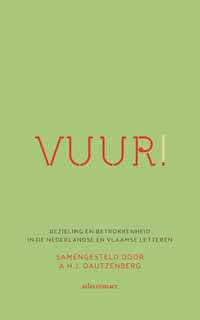

Op 26 november verschijnt Vuur! bij Uitgeverij Atlas Contact: een bloemlezing van A.H.J. Dautzenberg van Nederlandstalige schrijvers die het maatschappelijk engagement niet schuwden. De verschijning van Vuur! wordt donderdagmiddag 26 november tijdens het Wintertuinfestival gevierd met een speciaal symposium gewijd aan engagement in de kunsten.

Op 26 november verschijnt Vuur! bij Uitgeverij Atlas Contact: een bloemlezing van A.H.J. Dautzenberg van Nederlandstalige schrijvers die het maatschappelijk engagement niet schuwden. De verschijning van Vuur! wordt donderdagmiddag 26 november tijdens het Wintertuinfestival gevierd met een speciaal symposium gewijd aan engagement in de kunsten.

Naast A.H.J. Dautzenberg zijn onder andere Kristien Hemmerechts, Wunderbaum en Eva Meijer te gast.

Aan alle sprekers van de middag is de taak opgelegd om het publiek met hun vuur aan te steken. A.H.J. Dautzenberg opent het symposium. Kristien Hemmerechts probeert haar engagement over te dragen. Theatergezelschap Wunderbaum betreedt het podium om te laten zien dat engagement niet alleen in literatuur hoeft te bestaan. De band betonfraktion zorgt voor muzikale opschudding en Diederik Stapel leidt het publiek door de middag. Tijdens het symposium zullen ook de ‘vuurstenen’ worden ingewijd, twee originele plavuizen uit het gangpad van het huis van Multatuli in Rangbasbitung, waar hij als assistent-resident van Lebak woonde en werkte. Na het symposium worden de stenen in de collectie van het Multatulihuis opgenomen.

U bent van harte uitgenodigd om het symposium op donderdag 26 november bij te wonen. Kaarten voor het symposium kunt u kopen via www.wintertuinfestival.nl/donderdag

A.H.J. Dautzenberg debuteerde in 2010 met de absurdistische verhalenbundel Vogels met zwarte poten kun je niet vreten. Sindsdien schreef hij verschillende romans en verhalenbundels waarin hij journalistieke en morele dilemma’s aansnijdt en geldt hij als een van de meest controversiële schrijvers van Nederland.

Kristien Hemmerechts publiceerde talloze romans en ontving onder meer de Frans Kellendonkprijs voor haar gehele oeuvre. Recente werken als De vrouw die de honden eten gaf, waarin ze in de huid kroop van de ex-vrouw van Dutroux, en Alles verandert, waarin ze de sekse van de personages uit In ongenade van Coetzee verwisselt, deden veel stof opwaaien.

Beeldend kunstenaar, filosoof, schrijver en singer-songwriter Eva Meijer probeert het publiek aan te steken met het engagement uit haar roman Dagpauwoog, waarin het dierenactivisme centraal staat.

Theatergezelschap Wunderbaum betreedt het podium om te laten zien dat engagement niet alleen in literatuur hoeft te bestaan. Wunderbaum maakt voorstellingen over actuele thema’s. Het gehele oeuvre werd in 2007 bekroond met de Mary Dresselhuysprijs.

De band Betonfraktion zorgt voor muzikale opschudding en Dautzenbergs goede vriend Diederik Stapel leidt het publiek door de middag.

Vuur! Symposium over engagement in de kunsten met A.H.J. Dautzenberg

Datum: donderdag 26 november 2015

Locatie: CC3, Mercatorpad 1, Radboud Universiteit, Nijmegen

Aanvang: 16.00u, Zaal open: 15.45u

Entree: € 6 / € 3 (CJP-/ studentenpas)

Meer info en kaartverkoop: www.wintertuinfestival.nl/donderdag

Over Vuur! De Nederlandse en Vlaamse literatuur heeft de nodige hemelbestormers voortgebracht. Schrijvers die niet met hun rug naar de samenleving gingen staan, maar die meenden dat hun ideeën en geschriften het verschil konden maken. Hun vervoering leverde bezielde boeken op. In Vuur! bloemleest A.H.J. Dautzenberg Nederlandstalige schrijvers die het maatschappelijk engagement niet schuwden. Van Multatuli tot Dimitri Verhulst, van Herman Heijermans tot Kristien Hemmerechts. In een tijd waarin engagement een vies woord lijkt, maar waarin schrijvers ook regelmatig te weinig maatschappelijke betrokkenheid verweten wordt, is Vuur! een hommage én een aansporing.

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: A.H.J. Dautzenberg, Archive C-D, Art & Literature News, MONTAIGNE, Wintertuin Festival

Stefan Zweig

(1881-1942)

Die Nacht der Gnaden

Ein Reigen Sonette

I.

Ein schwarzer Flor umkränzte die Gelände.

Wie Boote segelten am Himmelsmeer

Die letzten lauen Abendwolken her

Und gossen Schattenschleier um die Wände.

Das Zimmer dunkelte. Die heißen Hände

Der beiden lagen willenlos und schwer

In ihrem Schoß und suchten sich nicht mehr.

Die leeren Worte waren längst zu Ende.

Sie bebten beide. Und ein Schweigen kam

Mit banger Schwüle. Er hielt sie umfangen

Und flehte ohne Wort: “Sei mein! Sei mein!”

Sie zitterte. Die Blüte junger Scham

Wuchs purpurn über ihre blassen Wangen,

Und Tränen stammelten: “Es darf nicht sein.”

II.

Da ließ er sie: “Ich will dich nicht betören.

Sei du nur mein, wenn du es längst schon bist.

Nicht eine Gabe sollst du mir gewähren,

Gib mir nur das, was lang mein eigen ist.

Sei mein, so wie sich mit den Sternenchören

Der Himmel flutend in die Nacht ergießt,

Und Seligkeiten werden uns gehören,

Durch die der Strom der Ewigkeiten fließt.

Willst du den Kelch der Sünde nicht nur nippen

Und ganz dein Sein an eine Nacht verschwenden,

So wird bis an die Grenze deiner Tage

Ein Leuchten sprühn von ungeahnten Bränden

Aus dieser Nacht!” – Wie eine bange Klage

Umfing ein zartes Lächeln ihre Lippen:

III.

“Was alle andern Schmach und Sünde nennen,

Wär mir ein Pfad zu lichten Seligkeiten,

Wenn nur auf meinem Mund, dem schmerzgeweihten,

Die roten Male deiner Küsse brennen.

Doch du bist Horcher in die Ewigkeiten,

Von denen mich die dunklen Wolken trennen.

Mich ließ nur Sehnsucht meine Jugend kennen

Und nicht die Träume, die zum Lichte leiten.

Drum will ich mich nicht deinem Willen senken,

Ob auch ein jeder Puls in meinen Gliedern

Mit seiner Sehnsucht dir schon angehört.

Ich bin zu arm, dir Liebe zu erwidern,

Und bin zu stolz, um Armut zu verschenken,

Denn sieh: Ich weiß, ich bin nicht deiner wert!”

IV.

Da sprach er sanft – und wie von Orgeldröhnen

War seine Stimme wundersam bewegt -:

“Wer so wie du den Glanz der Güte trägt,

Ist auserwählt, ein Leben licht zu krönen.

Oh fühlst du nicht, wie in verwandten Tönen

In uns der rasche Takt des Blutes schlägt

Und wilde Flamme in der Tiefe regt,

Um sich in unserm Einklang zu versöhnen?

Ich glüh in dir, du glühst in meinem Leben,

Zu neuer Einheit drängt dein junger Schoß

Und will den Ewigkeiten sich vermählen.

Sei mein! Erst wenn uns übermächtig groß

Die Schauer eigner Schöpfungslust durchbeben,

Rauscht eine Welt in unsern freien Seelen.”

V.

So sprach er glühend. Und sie beide standen

Im Bann des Blutes, wortlos wie verzagte

Verlorne Pilger nah den lichten Landen,

Wo schon das Frührot der Erfüllung tagte.

Dann kam ein Seufzen … als ob Weinen klagte …

Ein Knistern wie von sinkenden Gewanden …

Ein banger Ruf … Und als sein Auge fragte,

Ob sie der Sehnsucht wildes Wort verstanden,

Ward jählings Glanz in seinen Blick getragen,

Wie Glanz von Firnen … Aus dem Dunkel blühte

Gleich einer Lilie schlank und nackt ihr Leib.

Da schwieg sein Herz. Er wußte nicht zu sagen,

Wie ein Gebet durchdrang ihn ihre Güte,

Und diese Nacht ward sie ihm Gott und Weib.

VI.

Ihm aber war in dieser Nacht der Gnaden,

Als fühlte er die Welt zum erstenmal.

Er sah die Sterne auf beglänzten Pfaden

Wie Boten wandeln durch den Himmelssaal,

Sah weit das Leuchten über den Gestaden,

Der Morgenröte purpurblassen Strahl,

Fühlte die Winde, wie sie duftbeladen

Sich wiegten in den Wipfeln ohne Zahl,

Sah Frucht und Blüte über den Geländen

Und Saat und Segen. Erst in dieser Nacht

Ward ihm das Wunder aller Schöpfung wahr.

Und wie ein Kind, das in die Welt erwacht,

Nahm er aus diesen milden Frauenhänden

Die neue Pracht, die längst sein eigen war.

Stefan Zweig poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive Y-Z, Stefan Zweig, Zweig, Stefan

Ernest Dowson

(1867-1900)

The Dead Child

Sleep on, dear, now

The last sleep and the best,

And on thy brow,

And on thy quiet breast

Violets I throw.

Thy scanty years

Were mine a little while;

Life had no fears

To trouble thy brief smile

With toil or tears.

Lie still, and be

For evermore a child!

Not grudgingly,

Whom life has not defiled,

I render thee.

Slumber so deep,

No man would rashly wake;

I hardly weep,

Fain only, for thy sake,

To share thy sleep.

Yes, to be dead,

Dead, here with thee to-day,

When all is said

’Twere good by thee to lay

My weary head.

The very best!

Ah, child so tired of play,

I stand confessed:

I want to come thy way,

And share thy rest.

Ernest Dowson poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive C-D, Dowson, Ernest

Ivo van Leeuwen: You order we ignore

# meer op website ivo van leeuwen

fleursdumal.nl digital magazine

More in: Exhibition Archive, Illustrators, Illustration, Ivo van Leeuwen

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature