Fleurs du Mal Magazine

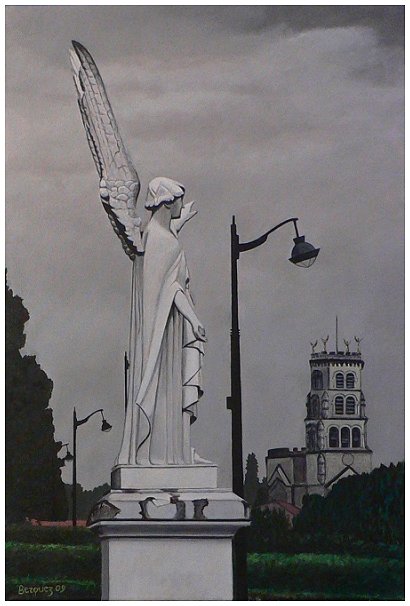

Vincent Berquez: Angel of Bugloze

Vincent Berquez is a London–based artist and poet. He has published in Britain, Europe, America and New Zealand. His work is in many anthologies, collections and magazine worldwide. Vincent Berquez was requested to write a Tribute as part of ‘Poems to the American People’ for the Hastings International Poetry Festival for 9/11, read by the mayor of New York at the podium. He has also been commissioned to write a eulogy by the son of Chief Albert Nwanzi Okoluko, the Ogimma Obi of Ogwashi-Uku to commemorate the death of his father. Berquez has been a judge many times, including for Manifold Magazine and had work read as part of Manifold Voices at Waltham Abbey. He has recited many times, including at The Troubadour and the Pitshanger Poets, in London. In 2006 his name was put forward with the Forward Prize for Literature. He recently was awarded a prize with Decanto Magazine. Berquez is now a member of London Voices who meet monthly in London, United Kingdom.

Vincent Berquez has also been collaborating in 07/08 with a Scottish composer and US film maker to produce a song-cycle of seven of his poems for mezzo-soprano and solo piano. These are being recorded at the Royal College of Music under the directorship of the concert pianist, Julian Jacobson. In 2009 he will be contributing 5 poems for the latest edition of A Generation Defining Itself, as well as 3 poems for Eleftheria Lialios’s forthcoming book on wax dolls published in Chicago. He also made poetry films that have been shown at various venues, including a Polish/British festival in London, Jan 07.

As an artist Vincent Berquez has exhibited world wide, winning prizes, such as at the Novum Comum 88’ Competition in Como, Italy. He has worked with an art’s group, called Eins von Hundert, from Cologne, Germany for over 16 years. He has shown his work at the Institute of Art in Chicago, US, as well as many galleries and institutions worldwide. Berquez recently showed his paintings at the Lambs Conduit Festival, took part in a group show called Gazing on Salvation, reciting his poetry for Lent and exhibiting paintings/collages. In October he had a one-man show at Sacred Spaces Gallery with his Christian collages in 2007. In 2008 Vincent Berquez had a solo show of paintings at The Foundlings Museum and in 2011 an exposition with new work in Langham Gallery London.

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Berquez, Vincent, FDM in London, Vincent Berquez

Joseph von Eichendorff

(1788-1857)

Durch! 2

Laß dich die Welt nicht fangen,

Brich durch, mein freudig Herz,

Ein ernsteres Verlangen

Erheb dich himmelwärts!

Greif in die goldnen Saiten,

Da spürst du, daß du frei,

Es hellen sich die Zeiten,

Aurora scheinet neu.

Es mag, will alles brechen,

Die gotterfüllte Brust

Mit Tönen wohl besprechen

Der Menschen Streit und Lust.

Und eine Welt von Bildern

Baut sich da auf so still,

Wenn draußen dumpf verwildern

Die alte Schönheit will.

Joseph von Eichendorff poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive E-F, CLASSIC POETRY

Martin Beversluis

Opstaan

We beeldden eens klantkaarten uit

hieven glazen en vertieften als een

pretpark waar het vertier van vertrok

al die landen van ooit vormden

samen onsamenhangende

continenten waar mensen enkel

de taal van dubbele tongen

spraken nog een rondje

nog een rondje

dan namen we aan dat zelfkennis

wijsheid was zo was zij aan ons

de wijsheid een waarheid van

kinderen en dronkelappen

Uiteindelijk tekenden we maar

bij het kruisje omdat daar de

schat lag naar onze vaste

overtuiging we herhaalden

onszelf als teken van stress

en we gingen ook wel eens

gewoon dood

tot het tijd was op te staan.

Martin Beversluis Stadsdichter Tilburg 2015 – 2017

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Beversluis, Martin, City Poets / Stadsdichters

Andrew Barton ‘Banjo’ Paterson

(1864 – 1941)

A Bushman’s Song

I’M travellin’ down the Castlereagh, and I’m a station hand,

I’m handy with the ropin’ pole, I’m handy with the brand,

And I can ride a rowdy colt, or swing the axe all day,

But there’s no demand for a station-hand along the Castlereagh. +

So it’s shift, boys, shift, for there isn’t the slightest doubt

That we’ve got to make a shift to the stations further out,

With the pack-horse runnin’ after, for he follows like a dog,

We must strike across the country at the old jig-jog.

This old black horse I’m riding—if you’ll notice what’s his brand,

He wears the crooked R, you see—none better in the land.

He takes a lot of beatin’, and the other day we tried,

For a bit of a joke, with a racing bloke, for twenty pounds a side.

It was shift, boys, shift, for there wasn’t the slightest doubt

That I had to make him shift, for the money was nearly out;

But he cantered home a winner, with the other one at the flog—

He’s a red-hot sort to pick up with his old jig-jog.

I asked a cove for shearin’ once along the Marthaguy:

“We shear non-union here,” says he. “I call it scab,” says I.

I looked along the shearin’ floor before I turned to go—

There were eight or ten dashed Chinamen a-shearin’ in a row.

It was shift, boys, shift, for there wasn’t the slightest doubt

It was time to make a shift with the leprosy about.

So I saddled up my horses, and I whistled to my dog,

And I left his scabby station at the old jig-jog.

I went to Illawarra, where my brother’s got a farm,

He has to ask his landlord’s leave before he lifts his arm;

The landlord owns the country side—man, woman, dog, and cat,

They haven’t the cheek to dare to speak without they touch their hat.

It was shift, boys, shift, for there wasn’t the slightest doubt

Their little landlord god and I would soon have fallen out;

Was I to touch my hat to him?—was I his bloomin’ dog?

So I makes for up the country at the old jig-jog.

But it’s time that I was movin’, I’ve a mighty way to go

Till I drink artesian water from a thousand feet below;

Till I meet the overlanders with the cattle comin’ down,

And I’ll work a while till I make a pile, then have a spree in town.

So, it’s shift, boys, shift, for there isn’t the slightest doubt

We’ve got to make a shift to the stations further out;

The pack-horse runs behind us, for he follows like a dog,

And we cross a lot of country at the old jig-jog.

Andrew Barton Paterson poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive O-P, CLASSIC POETRY

Annette von Droste-Hülshoff

(1797-1848)

Letzte Worte

Geliebte, wenn mein Geist geschieden,

So weint mir keine Träne nach;

Denn, wo ich weile, dort ist Frieden,

Dort leuchtet mir ein ew’ger Tag!

Wo aller Erdengram verschwunden,

Soll euer Bild mir nicht vergehn,

Und Linderung für eure Wunden,

Für euern Schmerz will ich erflehn.

Weht nächtlich seine Seraphsflügel

Der Friede übers Weltenreich,

So denkt nicht mehr an meinen Hügel,

Denn von den Sternen grüß’ ich euch!

Annette von Droste-Hülshoff poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive C-D, CLASSIC POETRY

Charles Cros

(1842 – 1888)

Cœur simple

Dans les douces tiédeurs des chambres d’accouchées

Quand à peine, à travers les fenêtres bouchées,

Entre un filet de jour, j’aime, humble visiteur,

Le bruit de l’eau qu’on verse en un irrigateur,

Et les cuvettes à l’odeur de cataplasme.

Puis la garde-malade avec son accès d’asthme,

Les couches, où s’étend l’or des déjections,

Qui sèchent en fumant devant les clairs tisons,

Me rappellent ma mère aux jours de mon enfance;

Et je bénis ma mère, et le ciel, et la

France !

Charles Cros poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive C-D, Cros, Charles

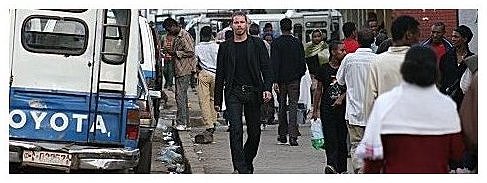

Na een slopende ziekte is op 12 augustus 2015 de schrijver, schilder en fotograaf David van Reen op 45-jarige leeftijd overleden.

David van Reen was op-en-top sportman toen (in 1998) een ernstig auto-ongeluk een einde aan zijn loopbaan maakte. Hij kwam wonderwel uit coma, leerde opnieuw lopen en knokte zich door een moeilijke periode heen. Als trainer van Afrikaanse hardlopers leerde hij de fascinerende cultuur en de mensen heel direct en diepgaand kennen.

Toen David van Reen 15 jaar geleden voor het eerst in Afrika kwam, schokte hem vooral de kloof tussen arm en rijk. Dat werd het thema in zijn werk als fotograaf en schrijver in zijn boeken. In die tijd trainde hij Keniaanse en Ethiopische atleten. Niet alleen om van hen kampioenen te maken. Als sportman was zijn credo: niet alleen succes telt, maar ook verliezen is waardevol en maakt je sterk.

Toen David van Reen 15 jaar geleden voor het eerst in Afrika kwam, schokte hem vooral de kloof tussen arm en rijk. Dat werd het thema in zijn werk als fotograaf en schrijver in zijn boeken. In die tijd trainde hij Keniaanse en Ethiopische atleten. Niet alleen om van hen kampioenen te maken. Als sportman was zijn credo: niet alleen succes telt, maar ook verliezen is waardevol en maakt je sterk.

David van Reen heeft zich in de laatste 15 jaar, met Stichting Lalibela, volledig ingezet voor de allerarmsten in Afrika. In de sloppenwijken van Nairobi werd hij graag gezien. Zijn fotoboeken en zijn romans Engelen der wrake en Anbessa’s dochter, met als hoofdthema het onrecht in de wereld, spelen in de armengetto’s van Kenia en Ethiopië.

David van Reen: “Op een van mijn reizen kwam ik in Woldia. Ik besloot om een wandeling te maken naar de Maryamkerk, een eind buiten het stadje. De heenweg bergop was ongeveer zes kilometer. Halverwege kwam ik een meisje tegen dat Netsannet heette. Haar naam betekent ‘vrijheid’. Gezien de blik in haar ogen zou ze geen passender naam kunnen hebben. Ze had een blikje bij zich met daarin een beetje stro en een paar eieren. Op mijn vraag wat ze met die eieren ging doen, zei ze dat ze naar de markt in Woldia ging. Ik vroeg haar waar ze woonde. Dat bleek dicht bij de Maryamkerk te zijn. Ik was verbaasd. Ze liep twaalf kilometer om twee eieren te verkopen! Haar optimisme en de levensvreugde die ze uitstraalde, maakten indruk op me. Toen ik later de foto’s die ik van Netsannet had gemaakt, afdrukte en weer zag hoe levensblij ze was, begon ik me pas af te vragen waarom wij hier op aarde zijn en of het jachtige leven dat wij westerlingen leiden, ons wel gelukkiger maakt dan Ethiopiërs. Zo ben ik met andere ogen naar deze mensen gaan kijken. Eerder al had het land me verrast door zijn schoonheid en zijn vriendelijke mensen.”

Uit: Het land van de verbrande gezichten. Leven in Ethiopië, foto’s en tekst van David van Reen, Uitg. De Geus.

De afscheidsplechtigheid heeft in besloten kring plaatsgevonden.

David van Reen was medewerker aan het magazine fleursdumal.nl

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: David van Reen, David van Reen Photos, In Memoriam, Photography

Katherine Mansfield

(1888 – 1923)

Sea

The Sea called—I lay on the rocks and said:

“I am come.”

She mocked and showed her teeth,

Stretching out her long green arms.

“Go away!” she thundered.

“Then tell me what I am to do,” I begged.

“If I leave you, you will not be silent,

But cry my name in the cities

And wistfully entreat me in the plains and forests;

All else I forsake to come to you—what must I do?”

“Never have I uttered your name,” snarled the Sea.

“There is no more of me in your body

Than the little salt tears you are frightened of shedding.

What can you know of my love on your brown rock

pillow….

Come closer.”

Katherine Mansfield poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive M-N, Katherine Mansfield, Mansfield, Katherine

Martin Beversluis

Maagden

Wij zijn een huis waar elke klok

een andere tijd aangeeft

dus blijft het altijd nu

ik graaf een kuil in een bos hout

jij zet de katten op sterk water

een onweerswolk drijft regenloos voorbij

ik zeg kijk

jij sluit je ogen en komt klaar

dan plukken we de bliksem van je benen

brandmerken onze vingers en tongen tot

naakte waarheid

we willen elkaar nooit echt leren kennen

lopen ieder apart in ditzelfde huis

jij bent tien uur ik vijf voor twaalf

het gaat maar in rondjes we halen nooit in

neuken als maagden puur voor de sensatie

maar nog lang niet voor de bevrediging.

Martin Beversluis poetry

Stadsdichter Tilburg 2015-2017

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Beversluis, Martin, City Poets / Stadsdichters

Ernest Dowson

(1867-1900)

A Last Word

Let us go hence: the night is now at hand;

The day is overworn, the birds all flown;

And we have reaped the crops the gods have sown;

Despair and death; deep darkness o’er the land,

Broods like an owl; we cannot understand

Laughter or tears, for we have only known

Surpassing vanity: vain things alone

Have driven our perverse and aimless band.

Let us go hence, somewhither strange and cold,

To Hollow Lands where just men and unjust

Find end of labour, where’s rest for the old,

Freedom to all from love and fear and lust.

Twine our torn hands! O pray the earth enfold

Our life-sick hearts and turn them into dust.

Ernest Dowson poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive C-D, Dowson, Ernest

Paul Klee

(1879-1940)

Liebestod im Lenz

Elisabeth: Suche nicht nach meinem Auge,

ich will es nicht haben.

Denn wie sollt’ ich wissen,

was du denkst dabei?

Tadle mich nicht

und noch weniger finde mich schön.

Ich tu was sie gut nennen

und ich will lassen, wovor meine Seele erschrickt.

Mein Weg ist aber umschleiert.

Jag mein Schritt;

und niemand kann mir helfen,

auch Du nicht.

Schon wieder seh ich Deine Augen fragen

und die meinen muß ich niederschlagen.

Wüßtest Du die Qual meiner Seele,

Dich triebe fern, was ich verhehle.

Flieh hin! Laß mich! Denk nicht an mich!

Vergiß, was ich zu Dir sprach! Weh.

Es ist keine Sonne im Lande meiner Seele.

Nur gen Abend liegt eine leichte Röte über den Bergen

und die Nacht ist im Anzug.

Ich hoffte einst auf wonnevolle Tage

und fühlte, mir wäre ein Anrecht darauf gegeben;

aber das war ein Traum des schlummernden Kindes

und erwachend geriet ich ins Dickicht und in die Dornen.

Ich glaubte recht zu tun und hörte sie tuscheln.

So handelte ich in Furcht,

und fand kein Entrinnen aus der Enge.

Mein Gott! Was sollen die langen Jungen

und was wollen die scheelen Blicke nebenaus?

Warum Worte über böse

Tage zu Fall bringen, warum?

Seither ist mein Mut dahin.

Ich fliehe das Neue

und will Vergangenes vergessen.

Ein Schemen bin ich

und könnte ohne Nahrung sein.

Und ach! Wie leise schlägt mein Herz.

Denn der Wellenschlag meiner Liebe

ist nur mehr murmelndes Brunnenrauschen

und mein Leben bald ein neues

und tiefer Schlaf.

Erst abends,

wenn die Nacht will anbrechen,

fahre ich hinaus im Kahn.

Und fernab von den lustigen Schauklern,

wo niemand mich sieht,

da weine ich lang und bitterlich.

[1900]

Paul Klee poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive K-L, Expressionism, Klee, Paul

Virginia Woolf

Virginia Woolf

(1882-1941)

8. The Mark on the Wall

(from: Monday or Tuesday)

Perhaps it was the middle of January in the present that I first looked up and saw the mark on the wall. In order to fix a date it is necessary to remember what one saw. So now I think of the fire; the steady film of yellow light upon the page of my book; the three chrysanthemums in the round glass bowl on the mantelpiece. Yes, it must have been the winter time, and we had just finished our tea, for I remember that I was smoking a cigarette when I looked up and saw the mark on the wall for the first time.

I looked up through the smoke of my cigarette and my eye lodged for a moment upon the burning coals, and that old fancy of the crimson flag flapping from the castle tower came into my mind, and I thought of the cavalcade of red knights riding up the side of the black rock. Rather to my relief the sight of the mark interrupted the fancy, for it is an old fancy, an automatic fancy, made as a child perhaps. The mark was a small round mark, black upon the white wall, about six or seven inches above the mantelpiece.

How readily our thoughts swarm upon a new object, lifting it a little way, as ants carry a blade of straw so feverishly, and then leave it . . . If that mark was made by a nail, it can’t have been for a picture, it must have been for a miniature — the miniature of a lady with white powdered curls, powder-dusted cheeks, and lips like red carnations. A fraud of course, for the people who had this house before us would have chosen pictures in that way — an old picture for an old room. That is the sort of people they were — very interesting people, and I think of them so often, in such queer places, because one will never see them again, never know what happened next. They wanted to leave this house because they wanted to change their style of furniture, so he said, and he was in process of saying that in his opinion art should have ideas behind it when we were torn asunder, as one is torn from the old lady about to pour out tea and the young man about to hit the tennis ball in the back garden of the suburban villa as one rushes past in the train.

But as for that mark, I’m not sure about it; I don’t believe it was made by a nail after all; it’s too big, too round, for that. I might get up, but if I got up and looked at it, ten to one I shouldn’t be able to say for certain; because once a thing’s done, no one ever knows how it happened. Oh! dear me, the mystery of life; The inaccuracy of thought! The ignorance of humanity! To show how very little control of our possessions we have — what an accidental affair this living is after all our civilization — let me just count over a few of the things lost in one lifetime, beginning, for that seems always the most mysterious of losses — what cat would gnaw, what rat would nibble — three pale blue canisters of book-binding tools? Then there were the bird cages, the iron hoops, the steel skates, the Queen Anne coal-scuttle, the bagatelle board, the hand organ — all gone, and jewels, too. Opals and emeralds, they lie about the roots of turnips. What a scraping paring affair it is to be sure! The wonder is that I’ve any clothes on my back, that I sit surrounded by solid furniture at this moment. Why, if one wants to compare life to anything, one must liken it to being blown through the Tube at fifty miles an hour — landing at the other end without a single hairpin in one’s hair! Shot out at the feet of God entirely naked! Tumbling head over heels in the asphodel meadows like brown paper parcels pitched down a shoot in the post office! With one’s hair flying back like the tail of a race-horse. Yes, that seems to express the rapidity of life, the perpetual waste and repair; all so casual, all so haphazard . . .

But after life. The slow pulling down of thick green stalks so that the cup of the flower, as it turns over, deluges one with purple and red light. Why, after all, should one not be born there as one is born here, helpless, speechless, unable to focus one’s eyesight, groping at the roots of the grass, at the toes of the Giants? As for saying which are trees, and which are men and women, or whether there are such things, that one won’t be in a condition to do for fifty years or so. There will be nothing but spaces of light and dark, intersected by thick stalks, and rather higher up perhaps, rose-shaped blots of an indistinct colour — dim pinks and blues — which will, as time goes on, become more definite, become — I don’t know what . . .

And yet that mark on the wall is not a hole at all. It may even be caused by some round black substance, such as a small rose leaf, left over from the summer, and I, not being a very vigilant housekeeper — look at the dust on the mantelpiece, for example, the dust which, so they say, buried Troy three times over, only fragments of pots utterly refusing annihilation, as one can believe.

The tree outside the window taps very gently on the pane . . . I want to think quietly, calmly, spaciously, never to be interrupted, never to have to rise from my chair, to slip easily from one thing to another, without any sense of hostility, or obstacle. I want to sink deeper and deeper, away from the surface, with its hard separate facts. To steady myself, let me catch hold of the first idea that passes . . . Shakespeare . . . Well, he will do as well as another. A man who sat himself solidly in an arm-chair, and looked into the fire, so — A shower of ideas fell perpetually from some very high Heaven down through his mind. He leant his forehead on his hand, and people, looking in through the open door — for this scene is supposed to take place on a summer’s evening — But how dull this is, this historical fiction! It doesn’t interest me at all. I wish I could hit upon a pleasant track of thought, a track indirectly reflecting credit upon myself, for those are the pleasantest thoughts, and very frequent even in the minds of modest mouse-coloured people, who believe genuinely that they dislike to hear their own praises. They are not thoughts directly praising oneself; that is the beauty of them; they are thoughts like this:

“And then I came into the room. They were discussing botany. I said how I’d seen a flower growing on a dust heap on the site of an old house in Kingsway. The seed, I said, must have been sown in the reign of Charles the First. What flowers grew in the reign of Charles the First?” I asked —(but, I don’t remember the answer). Tall flowers with purple tassels to them perhaps. And so it goes on. All the time I’m dressing up the figure of myself in my own mind, lovingly, stealthily, not openly adoring it, for if I did that, I should catch myself out, and stretch my hand at once for a book in self-protection. Indeed, it is curious how instinctively one protects the image of oneself from idolatry or any other handling that could make it ridiculous, or too unlike the original to be believed in any longer. Or is it not so very curious after all? It is a matter of great importance. Suppose the looking glass smashes, the image disappears, and the romantic figure with the green of forest depths all about it is there no longer, but only that shell of a person which is seen by other people — what an airless, shallow, bald, prominent world it becomes! A world not to be lived in. As we face each other in omnibuses and underground railways we are looking into the mirror that accounts for the vagueness, the gleam of glassiness, in our eyes. And the novelists in future will realize more and more the importance of these reflections, for of course there is not one reflection but an almost infinite number; those are the depths they will explore, those the phantoms they will pursue, leaving the description of reality more and more out of their stories, taking a knowledge of it for granted, as the Greeks did and Shakespeare perhaps — but these generalizations are very worthless. The military sound of the word is enough. It recalls leading articles, cabinet ministers — a whole class of things indeed which as a child one thought the thing itself, the standard thing, the real thing, from which one could not depart save at the risk of nameless damnation. Generalizations bring back somehow Sunday in London, Sunday afternoon walks, Sunday luncheons, and also ways of speaking of the dead, clothes, and habits — like the habit of sitting all together in one room until a certain hour, although nobody liked it. There was a rule for everything. The rule for tablecloths at that particular period was that they should be made of tapestry with little yellow compartments marked upon them, such as you may see in photographs of the carpets in the corridors of the royal palaces. Tablecloths of a different kind were not real tablecloths. How shocking, and yet how wonderful it was to discover that these real things, Sunday luncheons, Sunday walks, country houses, and tablecloths were not entirely real, were indeed half phantoms, and the damnation which visited the disbeliever in them was only a sense of illegitimate freedom. What now takes the place of those things I wonder, those real standard things? Men perhaps, should you be a woman; the masculine point of view which governs our lives, which sets the standard, which establishes Whitaker’s Table of Precedency, which has become, I suppose, since the war half a phantom to many men and women, which soon — one may hope, will be laughed into the dustbin where the phantoms go, the mahogany sideboards and the Landseer prints, Gods and Devils, Hell and so forth, leaving us all with an intoxicating sense of illegitimate freedom — if freedom exists . . .

In certain lights that mark on the wall seems actually to project from the wall. Nor is it entirely circular. I cannot be sure, but it seems to cast a perceptible shadow, suggesting that if I ran my finger down that strip of the wall it would, at a certain point, mount and descend a small tumulus, a smooth tumulus like those barrows on the South Downs which are, they say, either tombs or camps. Of the two I should prefer them to be tombs, desiring melancholy like most English people, and finding it natural at the end of a walk to think of the bones stretched beneath the turf . . . There must be some book about it. Some antiquary must have dug up those bones and given them a name . . . What sort of a man is an antiquary, I wonder? Retired Colonels for the most part, I daresay, leading parties of aged labourers to the top here, examining clods of earth and stone, and getting into correspondence with the neighbouring clergy, which, being opened at breakfast time, gives them a feeling of importance, and the comparison of arrow-heads necessitates cross-country journeys to the county towns, an agreeable necessity both to them and to their elderly wives, who wish to make plum jam or to clean out the study, and have every reason for keeping that great question of the camp or the tomb in perpetual suspension, while the Colonel himself feels agreeably philosophic in accumulating evidence on both sides of the question. It is true that he does finally incline to believe in the camp; and, being opposed, indites a pamphlet which he is about to read at the quarterly meeting of the local society when a stroke lays him low, and his last conscious thoughts are not of wife or child, but of the camp and that arrowhead there, which is now in the case at the local museum, together with the foot of a Chinese murderess, a handful of Elizabethan nails, a great many Tudor clay pipes, a piece of Roman pottery, and the wine-glass that Nelson drank out of — proving I really don’t know what.

No, no, nothing is proved, nothing is known. And if I were to get up at this very moment and ascertain that the mark on the wall is really — what shall we say? — the head of a gigantic old nail, driven in two hundred years ago, which has now, owing to the patient attrition of many generations of housemaids, revealed its head above the coat of paint, and is taking its first view of modern life in the sight of a white-walled fire-lit room, what should I gain? — Knowledge? Matter for further speculation? I can think sitting still as well as standing up. And what is knowledge? What are our learned men save the descendants of witches and hermits who crouched in caves and in woods brewing herbs, interrogating shrew-mice and writing down the language of the stars? And the less we honour them as our superstitions dwindle and our respect for beauty and health of mind increases . . . Yes, one could imagine a very pleasant world. A quiet, spacious world, with the flowers so red and blue in the open fields. A world without professors or specialists or house-keepers with the profiles of policemen, a world which one could slice with one’s thought as a fish slices the water with his fin, grazing the stems of the water-lilies, hanging suspended over nests of white sea eggs . . . How peaceful it is drown here, rooted in the centre of the world and gazing up through the grey waters, with their sudden gleams of light, and their reflections — if it were not for Whitaker’s Almanack — if it were not for the Table of Precedency!

I must jump up and see for myself what that mark on the wall really is — a nail, a rose-leaf, a crack in the wood?

Here is nature once more at her old game of self-preservation. This train of thought, she perceives, is threatening mere waste of energy, even some collision with reality, for who will ever be able to lift a finger against Whitaker’s Table of Precedency? The Archbishop of Canterbury is followed by the Lord High Chancellor; the Lord High Chancellor is followed by the Archbishop of York. Everybody follows somebody, such is the philosophy of Whitaker; and the great thing is to know who follows whom. Whitaker knows, and let that, so Nature counsels, comfort you, instead of enraging you; and if you can’t be comforted, if you must shatter this hour of peace, think of the mark on the wall.

I understand Nature’s game — her prompting to take action as a way of ending any thought that threatens to excite or to pain. Hence, I suppose, comes our slight contempt for men of action — men, we assume, who don’t think. Still, there’s no harm in putting a full stop to one’s disagreeable thoughts by looking at a mark on the wall.

Indeed, now that I have fixed my eyes upon it, I feel that I have grasped a plank in the sea; I feel a satisfying sense of reality which at once turns the two Archbishops and the Lord High Chancellor to the shadows of shades. Here is something definite, something real. Thus, waking from a midnight dream of horror, one hastily turns on the light and lies quiescent, worshipping the chest of drawers, worshipping solidity, worshipping reality, worshipping the impersonal world which is a proof of some existence other than ours. That is what one wants to be sure of . . . Wood is a pleasant thing to think about. It comes from a tree; and trees grow, and we don’t know how they grow. For years and years they grow, without paying any attention to us, in meadows, in forests, and by the side of rivers — all things one likes to think about. The cows swish their tails beneath them on hot afternoons; they paint rivers so green that when a moorhen dives one expects to see its feathers all green when it comes up again. I like to think of the fish balanced against the stream like flags blown out; and of water-beetles slowly raiding domes of mud upon the bed of the river. I like to think of the tree itself:— first the close dry sensation of being wood; then the grinding of the storm; then the slow, delicious ooze of sap. I like to think of it, too, on winter’s nights standing in the empty field with all leaves close-furled, nothing tender exposed to the iron bullets of the moon, a naked mast upon an earth that goes tumbling, tumbling, all night long. The song of birds must sound very loud and strange in June; and how cold the feet of insects must feel upon it, as they make laborious progresses up the creases of the bark, or sun themselves upon the thin green awning of the leaves, and look straight in front of them with diamond-cut red eyes . . . One by one the fibres snap beneath the immense cold pressure of the earth, then the last storm comes and, falling, the highest branches drive deep into the ground again. Even so, life isn’t done with; there are a million patient, watchful lives still for a tree, all over the world, in bedrooms, in ships, on the pavement, lining rooms, where men and women sit after tea, smoking cigarettes. It is full of peaceful thoughts, happy thoughts, this tree. I should like to take each one separately — but something is getting in the way . . . Where was I? What has it all been about? A tree? A river? The Downs? Whitaker’s Almanack? The fields of asphodel? I can’t remember a thing. Everything’s moving, falling, slipping, vanishing . . . There is a vast upheaval of matter. Someone is standing over me and saying —

“I’m going out to buy a newspaper.”

“Yes?”

“Though it’s no good buying newspapers . . . Nothing ever happens. Curse this war; God damn this war! . . . All the same, I don’t see why we should have a snail on our wall.”

Ah, the mark on the wall! It was a snail.

Monday or Tuesday, by Virginia Woolf

8. The Mark on the Wall

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Monday or Tuesday, Archive W-X, Woolf, Virginia

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature