Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Neerkomst

De dichter kuiert langs een haven. “Kijk”,

verplicht hij zich: de schepen die aankomen

zijn ver van de verlaten kade af. Komen ze

thuis of zijn ze halverwege het reizen? Hij weet

het niet. Schepen slapen als paarden, dat ziet

hij wel. Een onzichtbare zak haver voor de muil

hebben ze. Hun verzonnen vel trilt ongedurig

van nieuwsgierigheid naar al die verre einders.

Vermoeden van weemoed komt hem langs.

Langs pakhuizen maakt een meisje een radslag.

Niks tastend, voluit gaand. Hij prevelt wat

hij ziet: “Wat komt zij mooi neer.”

Bert Bevers

uit Afglans, Uitgeverij WEL, Bergen op Zoom, 1997

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Bevers, Bert

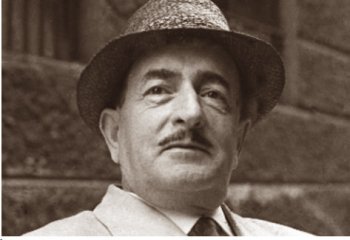

Salvatore Quasimodo

(1901-1968)

Wind at Tindari

Tindari, I know you

mild between broad hills, overhanging the waters

of the god’s sweet islands.

Today, you confront me

and break into my heart.

I climb airy peaks, precipices,

following the wind in the pines,

and the crowd of them, lightly accompanying me,

fly off into the air,

wave of love and sound,

and you take me to you,

you from whom I wrongly drew

evil, and fear of silence, shadow,

– refuge of sweetness, once certain –

and death of spirit.

It is unknown to you, that country

where each day I go down deep

to nourish secret syllables.

A different light strips you, behind the windows

clothed in night,

and another joy than mine

lies against you.

Exile is harsh

and the search, for harmony, that ended in you

changes today

to a precocious anxiousness for death,

and every love is a shield against sadness,

a silent stair in the gloom,

where you station me

to break my bitter bread.

Return, serene Tindari,

stir me, sweet friend,

to raise myself to the sky from the rock,

so that I might shape fear, for those who do not know

what deep wind has searched me.

Salvatore Quasimodo poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive Q-R

Ton van Reen

DE MOORD XV

SPELEN IN HET WOUD VAN TUBBS

Ik weet niet meer waarover ik die nacht droomde. Het moet een fijne droom zijn geweest, want toen ik ‘s morgens wakker werd, was ik blij. Ik liet niet merken dat ik wakker was. Integendeel. Ik bleef stil liggen en luisterde naar het kloppen van Alices hart, want ik lag nog steeds met mijn hoofd op haar borst. Ik voelde haar adem. Ik mocht me niet bewegen. Dan zou ik de marmot wakker maken. Die lag stil tussen mijn benen en zou het niet fijn vinden wakker gemaakt te worden. Overigens ben ik er nooit achtergekomen of de marmot ooit echt sliep. Hij hield wel zijn ogen dicht, maar hij voelde het als je naar hem keek.

In de wagen lag Cherubijn te ronken. Ik zou graag even zijn gaan kijken of zijn houten poot langs het bed naar beneden hing en of zijn kop scheef op het kussen lag en of zijn adem weer naar bedorven fruit rook.

Als ik mijn ogen opende en verder stil bleef liggen, kon ik door een spleet in de dekenzak naar buiten kijken. De wei dampte alsof er onder werd gestookt. De koeien vraten uit alle macht. De melker was bezig de draad om de wei aan te spannen. Die hing slap, in grote bogen, net als hoogspanningsdraden bij warm weer.

Over de weg liepen mensen uit Oeroe die wat door de morgen wilden wandelen. De morgen was hier, waar alleen de wei was en onze wagen, een witte wolk waar je goed doorheen kon kijken.

Sommige wandelaars bleven staan, keken naar de ademende slaapzak, maar konden niet zien wie erin lagen. Ze liepen verder, kwamen terug om opnieuw te blijven staan en naar de ademende dekenzak te kijken. Ze zochten de marmot. Ze waren verbaasd toen de dekenzak openging en Alice en ik onze hoofden naar buiten staken. Tegen elkaar zeiden ze: ‘Kijk, het meisje uit de zweef dat je niet mocht zoenen.’ Daar hadden ze toch wel respect voor. Toen de marmot langs mijn lijf naar buiten liep, gooiden ze ons geldstukjes toe.

Alice lachte. De mensen werden er gelukkiger door. Wat wilden ze nog meer. De morgen hadden ze al. Nu Alice tegen hen lachte, moesten ze genoeg energie hebben om een hele dag lang het leven vol te houden.

We kwamen uit de dekenzak. Alices rok was gekreukt. Ze streek er langs met haar strijkijzerhandjes. Weg waren de kreukels. Haar rok was weer even fleurig als de vorige dag. De mensen van Oeroe liepen door. De anderen die langs kwamen bleven niet meer staan. Naar rondlopende mensen kijk je niet. Wel naar mensen die liggen te slapen in een dekenzak en die je niet kunt zien. Dan moet je wel blijven staan om te zien wie er in de zak liggen en of je ‘goedenmorgen’ kunt zeggen. Zo waren de mensen van Oeroe. Bij al hun melancholie, veroorzaakt door de waterader die onder hun dorp liep, bleven ze toch vriendelijk. En waarom ook niet? Ze vierden de eerste naoorlogse kermis. Ook de kermissen hadden in de oorlog stilgelegen. Waarom weet ik niet. Je kon toch goed kermis vieren, ook al vocht men ergens aan het front? Of had het ook wat met het vaderland en de eigen doden te maken?

We hadden weer geld genoeg om eten te kopen. Dat hadden we aan de marmot te danken. De marmot die zonder het te weten de kost voor ons verdiende door over mijn lijf uit de slaapzak te kruipen om naar de mensen te kijken. Zo gemakkelijk heb ik de kost nooit meer verdiend. Later was ik niet meer tevreden met een stuk brood ‘s morgens en gebakken aardappelen ‘s avonds.

(wordt vervolgd)

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: - De moord

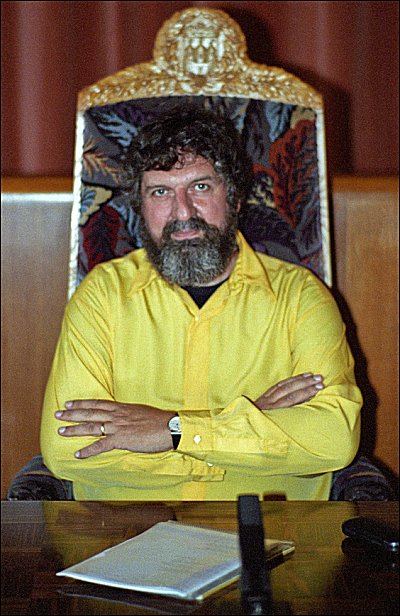

Laura van der Haar

winnaar NK Poetry Slam 2012

Laura van der Haar uit Amsterdam heeft op 14 december in Utrecht het Nederlands Kampioenschap Poetry Slam 2012 gewonnen. In muziekpaleis Rasa streden acht dichters om de landstitel. Het NK Poetry Slam werd voor de elfde maal gehouden.

In de jury zaten dichter Mustafa Stitou, cabaretière Katinka Polderman en critica Toef Jaeger. In de laatste slamronde werd uitsluitend gestemd door het publiek. In de finale moest Laura van der Haar het opnemen tegen de Vlaming Jee Kast. De finalisten gingen elkaar met woorden te lijf op het podium.

Het publiek stemde met overtuiging voor Laura van der Haar. Ook de jury sprak haar voorkeur uit voor Van der Haar vanwege ‘regels die spankracht hebben’ (Stitou) en de wijze waarop ze haar tegenstander Jee Kast ‘vriendelijk fileerde’ (Jaeger).

Laura van der Haar won de landstitel ‘Slampion 2012’, een geldbedrag van 1000 euro en de wisseltrofee ‘De Gouden Vink’, vernoemd naar dichter en inspirator van vele poetry slammers, Simon Vinkenoog. Van der Haar werkt als archeologe. Naast haar werk volgt ze de Schrijversvakschool en is ze redacteur bij het online literaire tijdschrift ‘Hard//Hoofd’. In mei 2013 zal ze Nederland vertegenwoordigen op het Wereldkampioenschap Poetry Slam in Parijs.

Een Poetry Slam is een wedstrijd voor beginnende dichters waarin zowel de tekst als de voordracht wordt beoordeeld. Tot eerdere winnaars behoren o.a. Erik Jan Harmens, Krijn Peter Hesselink, Ellen Deckwitz en Kira Wuck. Het NK Poetry Slam werd georganiseerd door het Poëziecircus, vanaf 1 januari 2013 het Literatuurhuis.

Alberquerquee baby

met een fletse bek van de kou zink je je huis uit

de stoep veert niet mee en de rest

ook al niet

er is een plek die je kent

waar iemand missen de vale gloed wordt

die soms boven steden hangt

steden, waar ‘s nachts een trein voorbijrijdt

waar gespeeld wordt, muziek

die harkend op een hoop veegt

wat uit jouw hoofd verdween

die hoop wordt een berg om in te schoppen

sneeuw, herfstblaadjes of

de plastic bekers na Koninginnedag, desnoods

je schopt

maar zij verdwijnt niet

jouw Albuquerquee baby

en met boliderode lippen

drukt ze vlinders in je kraag

Laura van der Haar

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive G-H, Poetry Slam, THEATRE

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (35)

Shoot! (Si Gira, 1926)The Notebooks of Serafino Gubbio, Cinematograph Operator by Luigi Pirandello. Translated from the Italian by C. K. Scott Moncrieff

BOOK VII

4

Turn the handle; I have turned it. I have kept my word: to the end. But the vengeance that I sought to accomplish upon the obligation imposed on me, as the slave of a machine, to serve up life to my machine as food, life has chosen to turn back upon me. Very good. No one henceforward can deny that I have now arrived at perfection.

As an operator I am now, truly, perfect.

About a month after the appalling disaster which is still being discussed everywhere, I bring these notes to an end.

A pen and a sheet of paper: there is no other way left to me now in which I can communicate with my fellow-men. I have lost my voice; I am dumb now for ever. Elsewhere in these notes I have written: “I suffer from this silence of mine, into which everyone comes, as into a place of certain hospitality. ‘I should like now my silence to close round me altogether’.” Well, it has closed round me. I could not be better qualified to act as the servant of a machine.

But I must tell you the whole story, as it happened.

The wretched fellow went, next morning, to Borgalli to complain forcibly of the ridiculous figure which, as he was informed, Polacco intended to make him cut with these precautions.

He insisted at all costs that the orders should be cancelled, offering to give them all a specimen, if they needed it, of his well-known skill as a marksman. Polacco excused himself to Borgalli, saying that he had taken these measures not from any want of confidence in Nuti’s courage or sureness of eye, but from prudence, knowing Nuti to be extremely nervous, as for that matter he was shewing himself to be at that moment by uttering this excited protest, instead of the grateful, friendly thanks which Polacco had a right to expect from him.

“Besides,” he unfortunately added, pointing to me, “you see, Commendatore, there’s Gubbio here too, who has to go into the cage….”

The poor wretch looked at me with such contempt that I immediately turned upon Polacco, exclaiming:

“No, no, my dear fellow! Don’t bother about me, please! You know very well that I shall go on quietly turning my handle, even if I see this gentleman in the jaws and claws of the beast!”

There was a laugh from the actors who had gathered round to listen; whereupon Polacco shrugged his shoulders and gave way, or pretended to give way. Fortunately for me, as I learned afterwards, he gave secret instructions to Fantappiè and one of the others to conceal their weapons and to stand ready for any emergency. Nuti went off to his dressing-room to put on his sporting clothes; I went to the Negative Department to prepare my machine for its meal. Fortunately for the company, I drew a much larger supply of film than would be required, to judge approximately by the length of the scene. When I returned to the crowded lawn, by the side of the enormous cage, set with a forest scene, the other cage, with the tiger inside it, had already been carried out and placed so that the two cages opened into one another. It only remained to pull up the door of the smaller cage.

Any number of actors from the four companies had assembled on either side, close to the cage, so that they could see between the tree trunks and branches that concealed its bars. I hoped for a moment that the Nestoroff, having secured her object, would at least have had the prudence not to come. But there she was, alas!

She stood apart from the crowd, a little way off, with Carlo Ferro, dressed in bright green, and was smiling as she repeatedly nodded her head in agreement with what Ferro was saying to her, albeit from the grim attitude in which he stood by her side it seemed evident that such a smile was not the appropriate answer to his words. But it was meant for the others, that smile, for all of us who stood watching her, and was also for me, a brighter smile, when I fixed my gaze on her; and it said to me once again that she was not afraid of anything, because the greatest possible evil for her I already knew: she had it by her side–there it was–Ferro; he was her punishment, and to the very end she I was determined, with that smile, to taste its, full flavour in the coarse words which he was probably addressing to her at that moment.

Taking my eyes from her, I sought those of Nuti. They were clouded. Evidently he too had caught sight of the Nestoroff there in the distance; but he chose to pretend that he had not. His face had grown stiff. He made an effort to smile, but smiled with his lips alone, a faint, nervous smile, at what some one was saying to him. With his black velvet cap on his head, with its long peak, his red coat, a huntsman’s brass horn slung over his shoulder, his white buckskin breeches fitting close to his thighs; booted and spurred, rifle in hand: he was ready.

The door of the big cage, through which ha and I were to enter, was opened from outside; to help us to climb in, two stage hands placed a pair of steps beneath it. He entered the cage first, then I. While I was setting up my machine on its tripod, which had been handed to me through the door of the cage, I noticed that Nuti first of all knelt down on the spot marked out for him, then rose and went across to thrust apart the boughs at one side of the cage, as though he were making a loophole there. I alone was in a position to ask him:

“Why?”

But the state of feeling that had grown up between us did not allow of our exchanging a single word at this stage. His action might therefore have been interpreted by me in several ways, which would have left me uncertain at a moment when the most absolute and precise certainty was essential. And then it was just as though Nuti had not moved at all; not only did I not think any more about his action, it was exactly as though I had not even noticed it.

He took his stand on the spot marked out for him, raising his rifle; I gave the signal:

“Ready.”

We heard from the other cage the sound of the door being pulled up. Polacco, perhaps seeing the animal begin to move towards the open door, shouted amid the silence:

“Are you ready? Shoot!”

And I began to turn the handle, with my eyes on the tree trunks in the background, through which the animal’s head was now protruding, lowered, as though peering out to explore the country; I saw that head slowly drawn back, the two forepaws remain firm, close together, and the hindlegs gradually, silently gather strength and the back rise in an arch in readiness for the spring. My hand was impassively keeping the time that I had set for its movement, faster, slower, dead slow, as though my will had flowed down–firm, lucid, inflexible–into my wrist, and from there had assumed entire control, leaving my brain free to think, my heart to feel; so that my hand continued to obey even when with a pang of terror I saw Nuti take his aim from the beast and slowly turn the muzzle of his rifle towards the spot where a moment earlier he had opened a loophole among the boughs, and fire, and the tiger immediately spring upon him and become merged with him, before my eyes, in a horrible writhing mass. Drowning the most deafening shouts that came from all the actors outside the cage as they ran instinctively towards the Nestoroff who had fallen at the shot, drowning the cries of Carlo Ferro, I heard there in the cage the deep growl of the beast and the horrible gasp of the man as he lay helpless in its fangs, in its claws, which were tearing his throat and chest; I heard, I heard, I kept on hearing above that growl, above that gasp, the continuous ticking of the machine, the handle of which my hand, alone, of its own accord, still kept on turning; and I waited for the beast to spring next upon me, having brought him down; and the moments of waiting seemed to me an eternity, and it seemed to me that throughout eternity I had been counting them, as I turned, still turned the handle, powerless to stop, when finally an arm was thrust in between the bars, carrying a revolver, and fired a shot point blank into the tiger’s ear over the mangled corpse of Nuti; and I was pulled back and dragged from the cage with the handle of the machine so tightly clasped in my fist that it was impossible at first to wrest it from me. I uttered no groan, no cry: my voice, from terror, had perished in my throat for ever.

Well, I have rendered the firm a service from which they will reap a fortune. As soon as I was able, I explained to the people who gathered round me terror-struck, first of all by signs, then in writing, that they were to take good care of the machine, which had been wrenched from my hand: that machine had in its maw the life of a man; I had given it that life to eat to the very last, until the moment when that arm had been thrust in to kill the tiger. There was a fortune to be extracted from this film, what with the enormous publicity and the morbid curiosity which the sordid atrocity of the drama of that slaughtered couple would everywhere arouse.

Ah, that it would fall to my lot to feed literally on the life of a man one of the many machines invented by man for his pastime, I could never have guessed. The life which this machine has devoured was naturally no more than it could be in a time like the present, in an age of machines; a production stupid in one aspect, mad in another, inevitably, and in the former more, in the latter rather less stamped with a brand of vulgarity.

I have found salvation, I alone, in my silence, with my silence, which has made me thus–according to the standard of the times–perfect. My friend Simone Pau will not understand this, more and more determined to drown himself in ‘superfluity’, the perpetual inmate of a Casual Shelter. I have already secured a life of ease with the compensation which the firm has given me for the service I have rendered it, and I shall soon be rich with the royalties which have been assigned to me from the hire of the monstrous film. It is true that I shall not know what to do with these riches; but I shall not reveal my embarrassment to anyone; least of all to Simone Pau, who comes every day to shake me, to abuse me, in the hope of forcing me out of this inanimate silence, which makes him furious. He would like to see me weep, would like me at least with my eyes to shew distress or anger; to make him understand by signs that I agree with him, that I too believe that life is there, in that ‘superfluity’ of his. I do not move an eyelid; I sit gazing at him, rigid, motionless, until he flies from the house in a rage. Poor Cavalena, from anoher angle, is studying on my behalf textbooks of nervous pathology, suggests injections and electric batteries, hovers round me to persuade me to agree to a surgical operation on my vocal chords; and Signorina Luisetta, penitent, heartbroken at my calamity, in which she chooses to detect an element of heroism, timidly lets me see now that she would like to hear issue, if not from my lips, at any rate from my heart a “yes” for herself.

No, thank you. Thanks to everybody. I have had enough. I prefer to remain like this. The times are what they are; life is what it is; and in the sense that I give to my profession, I intend to go on as I am–alone, mute and impassive–being the operator.

Is the stage set?

“Are you ready? Shoot….”

THE END

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (35)

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: -Shoot!, Archive O-P, Pirandello, Luigi, Pirandello, Luigi

E-Poetry 2013

17 – 20 June 2013

Kingston University-London

“The ‘poetry’ in ‘E-Poetry’ does not signal a genre preference but an origin. That is, making as a means of realizing art, a delight in digital literary invention…”

A legendary international digital literature event, E-POETRY was the first festival wholly dedicated to the digital literary arts. Occurring biennially on odd numbered years since its inception, it is the longest continuously-running festival of digital literature and scholarship in the field. We convene biennially to allow projects incubation time and to allow time for reflection. We are truly international, alternating between venues on both sides of the Atlantic to avoid splitting our public. This Festival is intended as a worldwide gathering, different perspectives convening at one time. Indeed, E-POETRY is markedly different: we try to give ALL presenters the attention they deserve. There are no concurrent sessions to split audiences or keynote addresses to promote hierarchical models. We encourage participants to attend the entire festival and we try to identify a unifying venue where we can gather our collective thoughts. Our aim is for all to receive the attention they deserve, engaging in a celebratory, consistently plenary occasion. We hope to build connections that are sustainable, energizing, and that reach across disciplines. More importantly, the “poetry” in “E-Poetry” does not signal a genre preference but an ORIGIN — MAKING as a means of realizing art, a delight in digital literary invention. Our emphasis is on the multiple literary and artistic ramifications of digital media writing and its critical reception through extending modes and practices that transcend limits of genre or specific technologies. We celebrate new voices, emergent thoughtful articulation, performance, and cultural breadth in expression. Thanks to our newly-constituted Board, the talents of our Local Convener, and most importantly — to you — we are looking forward to the next evolutionary stage of this carefully-curated, diverse, and constantly inspiring landmark festival, E-POETRY 2013 KINGSTON UNIVERSITY LONDON.

E-Poetry Advisory Board: Yves Abrioux (France), Amaranth Borsuk (USA), David Jhave Johnston (Canada), Leonardo Flores (Puerto Rico), Claudia Kozak (Argentina), Manuel Portela (Portugal), Laura Shackelford (USA); Local Convener: Maria Mencia (UK); E-Poetry Director: Loss Pequeño Glazier (USA)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: The talk of the town

foto kempis.nl

JACE van de Ven

De beek

Waar begonnen, was er eerst de zee

Of de sneeuw die drup drup drup weer water

Werd, dat neerwaarts ging en niet veel later

Stroompje was, dan beek van lieverlee

Als een kind bokspringt het naar benee

Blinkend in het zonlicht, dan weer staat er

Vol de maan op en geregeld gaat er

Spiegelend een wolk of boomkruin mee

Geile woerden, vis die springt en blinkt,

In een rietkraag staat de reiger stijf en

laat alleen de blaadjes langs zich drijven

Alles stroomt voorbij, maar oud instinct

Roept zalmen terug, krioelende lijven

Vechten naar wat was om daar te blijven

© 2010 JACE van de Ven: Drie sonnetten over water. De beek

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive U-V, Ven, Jace van de

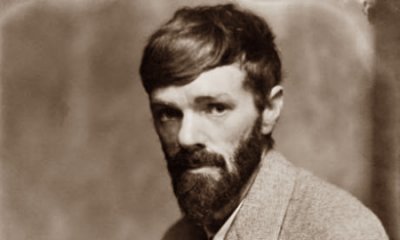

D. H. Lawrence

(1885-1930)

Trees in the Garden

Ah in the thunder air

how still the trees are!

And the lime-tree, lovely and tall, every leaf silent

hardly looses even a last breath of perfume.

And the ghostly, creamy coloured little tree of leaves

white, ivory white among the rambling greens

how evanescent, variegated elder, she hesitates on the green grass

as if, in another moment, she would disappear

with all her grace of foam!

And the larch that is only a column, it goes up too tall to see:

and the balsam-pines that are blue with the grey-blue blueness of

things from the sea,

and the young copper beech, its leaves red-rosy at the ends

how still they are together, they stand so still

in the thunder air, all strangers to one another

as the green grass glows upwards, strangers in the silent garden.

D.H. Lawrence poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive K-L, D.H. Lawrence, Lawrence, D.H.

photo: Kevin Carter

laaste woorde aan Kevin Carter

o god van grond

my uur het gekom

my dae was minder as gras

drie jaar van honger en dors

verlatenheid alom

sy wat my gebaar het is geslag

hy wat my verwek het is gejag

bang dag in dag uit en elke nag

Anyanya

slang venyn

alles pyn

alles dof

o god van grond

ek eet gras en stof

u engel se wraak

sy laaste waak

Carina van der Walt

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive W-X, Carina van der Walt, FDM in Africa, Walt, Carina van der

![]()

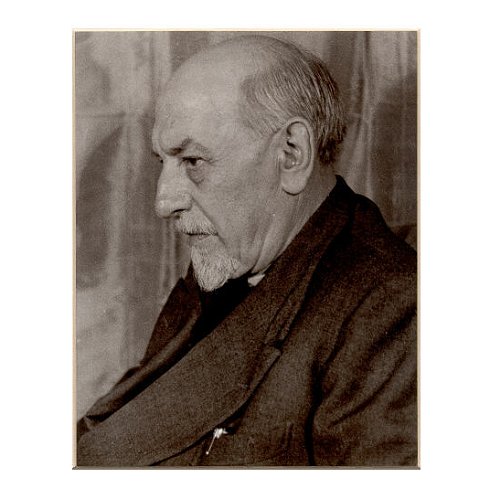

In Memoriam

Louis Th. Lehmann

(19-08-1920 – 23-12-2012)

Als ‘k dood ben

Als ‘k dood ben zijn mijn kleren rare dingen.

De overhemden, nieuw of dragensbroos,

de pakken hangend waar ze altijd hingen,

steeds wijzend naar omlaag, besluiteloos.

Ik was ze, ik alleen droeg ze altoos.

En omdat ze mij vaak vervingen,

of omdat ik hen uit hun winkel koos;

zij tonen iets van mijn herinneringen.

Oh vrienden, enigszins van mijn formaat,

ik roep U als de dood te wachten staat,

(maak ik het sterven bij bewustzijn mee)

‘k Geef U of leen, ‘t zou niet de eerste keer zijn

mijn pakken, vormt met hen die mij niet meer zijn

dan langs mijn kist een onzwart defilé.

L. Th. Lehmann (1920-2012) was dichter en schrijver, jurist, scheepsarcheoloog en muzikant. Hij schreef een oeuvre dat naast poëzie uit een tweetal romans, verhalen, reportages, essays, vertalingen, wetenschappelijke studies en een ‘surrealistische kameropera’ bestaat. Zijn dichterlijke werk is verzameld in de door T. van Deel bezorgde uitgave Gedichten 1939-1998 (2000). Met zijn lichte toon en virtuoos woordgebruik maakte Lehmann bij zijn debuut in 1940 diepe indruk op critici als Vestdijk en Ter Braak. In 1996, na meer dan dertig jaar als dichter te hebben gezwegen, keerde hij terug met de bundel Vluchtige steden, gevolgd door Gedichten 1939-1998. Dat Lehmanns kruit daarmee nog niet verschoten was, bewees hij met de lovend ontvangen bundels Toeschouw (2003), Wat boven kwam (2006) en Laden ledigen (keuze uit ongepubliceerd werk, 2008). Bron: De Bezige Bij

Louis Lehmann poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive K-L, In Memoriam, Lehmann, Louis Th.

Ernst Stadler

(1883-1914)

Aus der Dämmerung

In Kapellen mit schrägen Gewölben· zerfallnen Verließen

und Scheiben flammrot wie Mohn und wie Perlen grün

und Marmoraltären über verwitterten Fliesen

sah ich die Nächte wie goldne Gewässer verblühn:

der schlaffe Rauch zerstäubt aus geschwungnen Fialen

hing noch wie Nebel schwankend in starrender Luft·

auf Scharlachgewirken die bernsteinschillernden Schalen

schwammen wie Meergrundwunder im bläulichen Duft.

In dämmrigen Nischen die alten süßen Madonnen

lächelten müd und wonnig aus goldrundem Schein.

Rieselnde Träume hielten mich rankend umsponnen·

säuselnde Lieder sangen mich selig ein.

Des wirbelnden Frühlings leise girrendes Locken·

der Sommernächte Duftrausch weckte mich nicht:

Blaß aus Fernen läuteten weiße Glocken . .

Grün aus Kuppeln sickerte goldiges Licht . .

1904

Ernst Stadler poetry

fleursdumal.nl poetry magazine

More in: *War Poetry Archive, - Archive Tombeau de la jeunesse, Archive S-T, Archive S-T, Stadler, Ernst

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (34)

Shoot! (Si Gira, 1926). The Notebooks of Serafino Gubbio, Cinematograph Operator by Luigi Pirandello. Translated from the Italian by C. K. Scott Moncrieff

BOOK VII

3

And now, God willing, we have reached the end. Nothing remains now save the final picture of the killing of the tiger.

The tiger: yes, I prefer, if I must be distressed, to be distressed over her; and I go to pay her a visit, standing for the last time in front of her cage.

She has grown used to seeing me, the beautiful creature, and does not stir. Only she wrinkles her brows a little, annoyed; but she endures the sight of me as she endures the burden of this sunlit silence, lying heavy round about her, which here in the cage is impregnated with a strong bestial odour. The sunlight enters the cage and she shuts her eyes, perhaps to dream, perhaps so as not to see descending ‘upon her the stripes of shadow cast by the iron bars. Ah, she must be tremendously bored with life also; bored, too, with my pity for her; and I believe that to make it cease, with a fit reward, she would gladly devour me. This desire, which she realises that the bars prevent her from satisfying, makes her heave a deep sigh; and since she is lying outstretched, her languid head drooping on one paw, I see, when she sighs, a cloud of dust rise from the floor of the cage.

Her sigh, really distresses me, albeit I understand why she has emitted it; it is her sorrowful recognition of the deprivation to which she has been condemned of her natural right to devour man, whom she has every reason to regard as her enemy.

“To-morrow,” I tell her. “To-morrow, my dear, this torment will be at an end. It is true that this torment still means something to you, and that, when it is over, nothing will matter to you any more. But if you have to choose between this torment and nothing, perhaps nothing is preferable! A captive like this, far from your savage haunts, powerless to tear anyone to pieces, or even to frighten him, what sort of tiger are you? Hark! They are making ready the big cage out there…. You are accustomed already to hearing these hammer-blows, and pay no attention to them. In this respect, you see, you are more fortunate than man: man may think, when he hears the hammer-blows: ‘There, those are for me; that is the undertaker, getting my coffin ready.’ You are already there, in your coffin, and do not know it: it will be a far larger cage than this; and you will have the comfort of a touch of local colour there too: it will represent a glade in a forest. The cage in which you now are will be carried out there and placed so that it opens into the other. A stage hand will climb on the roof of this cage, and pull up the door, while another man opens the door of the other cage; and you will then steal in between the tree trunks, cautious and wondering. But immediately you will notice a curious ticking noise. Nothing! It will be I, winding my machine on its tripod; yes, I shall be in the cage too, beside you; but don’t pay any attention to me! Do you see? Standing a little way in front of me is another man, another man who takes aim at you and fires, ah! there you are on the ground, a dead weight, brought down in your spring…. I shall come up to you; with no risk to the machine, I shall register your last convulsions, and so good-bye!”

If it ends like that…

This evening, on coming out of the Positive Department, where, in view of Borgalli’s urgency, I have been lending a hand myself in the developing and joining of the sections of this monstrous film, I saw Aldo Nuti advancing upon me with the unusual intention of accompanying me home. I at once observed that he was trying, or rather forcing himself not to let me see that he had something to say to me.

“Are you going home?”

“Yes.”

“So am I.”

When we had gone some distance he asked:

“Have you been in the rehearsal theatre to-day?”

“No. I’ve been working downstairs, in the dark room.”

Silence for a while. Then he made a painful effort to smile, with what he intended for a smile of satisfaction.

“They were trying my scenes. Everyone was pleased with them. I should never have imagined that they would come out so well. One especially.

I wish you could have seen it.”

“Which one?”

“The one that shews me by myself for a minute, close up, with a finger on my lips, like this, engaged in thinking. It lasts a little too long, perhaps… my face is a little too prominent … and my eyes…. You can count my eyelashes. I thought I should never disappear from the screen.”

I turned to look at him; but he at once took refuge in an obvious reflexion:

“Yes!” he said. “Curious the effect our own appearance has on us in a photograph, even on a plain card, when we look at it for the first time. Why is it?”

“Perhaps,” I answered, “because we feel that we are fixed there in a moment of time which no longer exists in ourselves; which will remain, and become steadily more remote.”

“Perhaps!” he sighed. “Always more remote for us….”

“No,” I went on, “for the picture as well. The picture ages too, just as we gradually age. It ages, although it is fixed there for ever in that moment; it ages young, if we are young, because that young man in the picture becomes older year by year with us, in us.”

“I don’t follow you.”

“It is quite easy to understand, if you will think a little. Just listen: the time, there, of the picture, does not advance, does not keep moving on, hour by hour, with us, into the future; you expect it to remain fixed at that point, but it is moving too, in the opposite direction; it recedes farther and farther into the past, that time. Consequently the picture itself is a dead thing which as time goes on recedes gradually farther into the past: and the younger it is the older and more remote it becomes.”

“Ah, yes, I see what you mean…. Yes, yes,” he said. “But there is something sadder still. A picture that has grown old young and empty.”

“How do you mean, empty?”

“The picture of somebody who has died young.”

I again turned to look at him; but he at once added:

“I have a portrait of my father, who died quite young, at about my age; so long ago that I don’t remember him. I have kept it reverently, this picture of him, although it means nothing to me. It has grown old too, yes, receding, as you say, into the past. But time, in ageing the picture, has not aged my father; my father has not lived through this period of time. And he presents himself before me empty, devoid of all the life that for him has not existed; he presents himself before me with his old picture of himself as a young man, which says nothing to me, which cannot say anything to me, because he does not even know that I exist. It is, in fact, a portrait he had made of himself before he married; a portrait, therefore, of a time when he was not my father. I do not exist in him, there, just as all my life has been lived without him.”

“It is sad….”

“Sad, yes. But in every family, in the old photograph albums, on the little table by the sofa in every provincial drawing-room, think of all the faded portraits of people who no longer mean anything to us, of whom we no longer know who they were, what they did, how they died….”

All of a sudden he changed the subject to ask me, with a frown:

“How long can a film be made to last?”

He no longer turned to me as to a person with whom he took pleasure in conversing; but in my capacity as an operator. And the tone of his voice was so different, the expression of his face had so changed that I suddenly felt rise up in me once again that contempt which for some time past I have been cherishing for everything and everybody. Why did he wish to know how long a film could last? Had he attached himself to me to find out this? Or from a desire to make my flesh creep, leaving me to guess that he intended to do something rash that very day, so that our walk together should leave me with a tragic memory or a sense of remorse?

I felt tempted to stop short in front of him and to shout in his face:

“I say, my dear fellow, you can drop all that with me, because I don’t take the slightest interest in you! You can do all the mad things you please, this evening, to-morrow: I shan’t stir! You may perhaps have asked me how long a film can last to make me think that you are leaving behind you that picture of yourself with your finger on your lips? And you think perhaps that you are going to fill the whole world with pity and terror with that enlarged picture, in which ‘they can count your eyelashes’? How long do you expect a film to last?”

I shrugged my shoulders and answered:

“It all depends upon how often it is used.”

He too from the change in my tone must have realised that my attitude towards him had changed also, and he began to look at me in a way that troubled me.

The position was this: he was still here on earth a petty creature. Useless, almost a nonentity; but he existed, and was walking beside me, and was suffering. It was true that he was suffering, like all the rest of us, from life which is the true malady of us all. He was suffering for no worthy reason; but whose fault was it if he had been born so petty? Petty as he was, he was suffering, and his suffering was great for him, however unworthy…. It was from life that he suffered, from one of the innumerable accidents of life, which had fallen upon him to take from him the little that he had in him and rend end destroy him! At the moment he was here, Etili walking by my side, on a June evening, the sweetness of which he could not taste; to-morrow perhaps, since life had so turned against him, he would no longer exist: those legs of his would never be set in motion again to walk; he would never see again this avenue along which we were going; and he would never again clothe his feet in those fine patent leather shoes and those silk socks, would never again take pleasure, even in the height of his desperation, as he stood before the glass of his wardrobe every morning, in the elegance of the faultless coat upon his handsome slim body which I could put out my hand now and touch, still living, conscious, by ray side.

“Brother….”

No, I did not utter that word. There are certain words that we hear, in a fleeting moment; we do not say them. Christ could say them, who was not dressed like me and was not, like me, an operator. Amid a human society which delights in a cinematographic show and tolerates a profession like mine, certain words, certain emotions become ridiculous.

“If I were to call this Signor Nuti ‘brother’,” I thought, “he would take offence; because… I may have taught him a little philosophy as to pictures that grow old, but what am I to him? An operator: a hand that turns a handle.”

He is a “gentleman,” with madness already latent perhaps in the ivory box of his skull, with despair in his heart, but a rich “titled gentleman” who can well remember having known me as a poor student, a humble tutor to Giorgio Mirelli in the villa by Sorrento. He intends to keep the distance between me and himself, and obliges me to keep it too, now, between him and myself: the distance that time and my profession have created. Between him and me, the machine.

“Excuse me,” he asked, just as we were reaching the house, “how will you manage to-morrow about taking the scene of the shooting of the tiger?”

“It is quite easy,” I answered. “I shall be standing behind you.”

“But won’t there be the bars of the cage, all the plants in between?”

“They won’t be in my way. I shall be inside the cage with you.”

He stood and stared at me in surprise:

“You will be inside the cage too?”

“Certainly,” I answered calmly.

“And if… if I were to miss?”

“I know that you are a crack shot. Not that it will make any difference. To-morrow all the actors will be standing round the cage, looking on. Several of them will be armed and ready to fire if you miss.”

He stood for a while lost in thought, as though this information had annoyed him.

Then: “They won’t fire before I do?” he said.

“No, of course not. They will fire if it is necessary.”

“But in that case,” he asked, “why did that fellow… that Signor Ferro insist upon all those conditions, if there is really no danger?”

“Because in Ferro’s case there might perhaps not have been all those others, outside the cage, armed.”

“Ah! Then they are for me? They have taken these precautions for me? How ridiculous! Whose doing is it? Yours, perhaps?”

“Mine, no. What have I got to do with it?”

“How do you know about it, then?”

“Polacco said so.”

“Said so to you? Then it was Polacco? Ah, I shall have something to say to him to-morrow morning! I won’t have it, do you understand? I won’t have it!”

“Are you addressing me?”

“You too!”

“Dear Sir, let me assure you that what you say leaves me perfectly indifferent: hit or miss your tiger; do all the mad things you like inside the cage: I shall not stir a finger, you may be sure of that. Whatever happens, I shall remain quite impassive and go on turning my handle. Bear that in mind, if you please!”

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (34)

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: -Shoot!, Archive O-P, Pirandello, Luigi

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature