Fleurs du Mal Magazine

My Soul Is Dark

My soul is dark – Oh! quickly string

The harp I yet can brook to hear;

And let thy gentle fingers fling

Its melting murmurs o’er mine ear.

If in this heart a hope be dear,

That sound shall charm it forth again:

If in these eyes there lurk a tear,

‘Twill flow, and cease to burn my brain.

But bid the strain be wild and deep,

Nor let thy notes of joy be first:

I tell thee, minstrel, I must weep,

Or else this heavy heart will burst;

For it hath been by sorrow nursed,

And ached in sleepless silence, long;

And now ’tis doomed to know the worst,

And break at once – or yield to song.

George Gordon Byron

(1788 – 1824)

My Soul Is Dark

(Poem)

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Archive A-B, Byron, Lord

OLD ABE’S CONVERSION

The Negro population of the little Southern town of Danvers was in a state of excitement such as it seldom reached except at revivals, baptisms, or on Emancipation Day. The cause of the commotion was the anticipated return of the Rev. Abram Dixon’s only son, Robert, who, having taken up his father’s life-work and graduated at one of the schools, had been called to a city church.

When Robert’s ambition to take a college course first became the subject of the village gossip, some said that it was an attempt to force Providence. If Robert were called to preach, they said, he would be endowed with the power from on high, and no intervention of the schools was necessary. Abram Dixon himself had at first rather leaned to this side of the case. He had expressed his firm belief in the theory that if you opened your mouth, the Lord would fill it. As for him, he had no thought of what he should say to his people when he rose to speak. He trusted to the inspiration of the moment, and dashed blindly into speech, coherent or otherwise.

When Robert’s ambition to take a college course first became the subject of the village gossip, some said that it was an attempt to force Providence. If Robert were called to preach, they said, he would be endowed with the power from on high, and no intervention of the schools was necessary. Abram Dixon himself had at first rather leaned to this side of the case. He had expressed his firm belief in the theory that if you opened your mouth, the Lord would fill it. As for him, he had no thought of what he should say to his people when he rose to speak. He trusted to the inspiration of the moment, and dashed blindly into speech, coherent or otherwise.

Himself a plantation exhorter of the ancient type, he had known no school except the fields where he had ploughed and sowed, the woods and the overhanging sky. He had sat under no teacher except the birds and the trees and the winds of heaven. If he did not fail utterly, if his labour was not without fruit, it was because he lived close to nature, and so, near to nature’s God. With him religion was a matter of emotion, and he relied for his results more upon a command of feeling than upon an appeal to reason. So it was not strange that he should look upon his son’s determination to learn to be a preacher as unjustified by the real demands of the ministry.

But as the boy had a will of his own and his father a boundless pride in him, the day came when, despite wagging heads, Robert Dixon went away to be enrolled among the students of a growing college. Since then six years had passed. Robert had spent his school vacations in teaching; and now, for the first time, he was coming home, a full-fledged minister of the gospel.

It was rather a shock to the old man’s sensibilities that his son’s congregation should give him a vacation, and that the young minister should accept; but he consented to regard it as of the new order of things, and was glad that he was to have his boy with him again, although he murmured to himself, as he read his son’s letter through his bone-bowed spectacles: “Vacation, vacation, an’ I wonder ef he reckons de devil’s goin’ to take one at de same time?”

It was a joyous meeting between father and son. The old man held his boy off and looked at him with proud eyes.

“Why, Robbie,” he said, “you—you’s a man!”

“That’s what I’m trying to be, father.” The young man’s voice was deep, and comported well with his fine chest and broad shoulders.

“You’s a bigger man den yo’ father ever was!” said his mother admiringly.

“Oh, well, father never had the advantage of playing football.”

The father turned on him aghast. “Playin’ football!” he exclaimed. “You don’t mean to tell me dat dey ‘lowed men learnin’ to be preachers to play sich games?”

“Oh, yes, they believe in a sound mind in a sound body, and one seems to be as necessary as the other in fighting evil.”

Abram Dixon shook his head solemnly. The world was turning upside down for him.

“Football!” he muttered, as they sat down to supper.

Robert was sorry that he had spoken of the game, because he saw that it grieved his father. He had come intending to avoid rather than to combat his parent’s prejudices. There was no condescension in his thought of them and their ways. They were different; that was all. He had learned new ways. They had retained the old. Even to himself he did not say, “But my way is the better one.”

His father was very full of eager curiosity as to his son’s conduct of his church, and the son was equally glad to talk of his work, for his whole soul was in it.

“We do a good deal in the way of charity work among the churchless and almost homeless city children; and, father, it would do your heart good if you could only see the little ones gathered together learning the first principles of decent living.”

“Mebbe so,” replied the father doubtfully, “but what you doin’ in de way of teachin’ dem to die decent?”

The son hesitated for a moment, and then he answered gently, “We think that one is the companion of the other, and that the best way to prepare them for the future is to keep them clean and good in the present.”

“Do you give ’em good strong doctern, er do you give ’em milk and water?”

“I try to tell them the truth as I see it and believe it. I try to hold up before them the right and the good and the clean and beautiful.”

“Humph!” exclaimed the old man, and a look of suspicion flashed across his dusky face. “I want you to preach fer me Sunday.”

It was as if he had said, “I have no faith in your style of preaching the gospel. I am going to put you to the test.”

Robert faltered. He knew his preaching would not please his father or his people, and he shrank from the ordeal. It seemed like setting them all at defiance and attempting to enforce his ideas over their own. Then a perception of his cowardice struck him, and he threw off the feeling that was possessing him. He looked up to find his father watching him keenly, and he remembered that he had not yet answered.

“I had not thought of preaching here,” he said, “but I will relieve you if you wish it.”

“De folks will want to hyeah you an’ see what you kin do,” pursued his father tactlessly. “You know dey was a lot of ’em dat said I oughn’t ha’ let you go away to school. I hope you’ll silence ’em.”

Robert thought of the opposition his father’s friends had shown to his ambitions, and his face grew hot at the memory. He felt his entire inability to please them now.

“I don’t know, father, that I can silence those who opposed my going away or even please those who didn’t, but I shall try to please One.”

It was now Thursday evening, and he had until Saturday night to prepare his sermon. He knew Danvers, and remembered what a chill fell on its congregations, white or black, when a preacher appeared before them with a manuscript or notes. So, out of concession to their prejudices, he decided not to write his sermon, but to go through it carefully and get it well in hand. His work was often interfered with by the frequent summons to see old friends who stayed long, not talking much, but looking at him with some awe and a good deal of contempt. His trial was a little sorer than he had expected, but he bore it all with the good-natured philosophy which his school life and work in a city had taught him.

The Sunday dawned, a beautiful, Southern summer morning; the lazy hum of the bees and the scent of wild honeysuckle were in the air; the Sabbath was full of the quiet and peace of God; and yet the congregation which filled the little chapel at Danvers came with restless and turbulent hearts, and their faces said plainly: “Rob Dixon, we have not come here to listen to God’s word. We have come here to put you on trial. Do you hear? On trial.”

And the thought, “On trial,” was ringing in the young minister’s mind as he rose to speak to them. His sermon was a very quiet, practical one; a sermon that sought to bring religion before them as a matter of every-day life. It was altogether different from the torrent of speech that usually flowed from that pulpit. The people grew restless under this spiritual reserve. They wanted something to sanction, something to shout for, and here was this man talking to them as simply and quietly as if he were not in church.

As Uncle Isham Jones said, “De man never fetched an amen”; and the people resented his ineffectiveness. Even Robert’s father sat with his head bowed in his hands, broken and ashamed of his son; and when, without a flourish, the preacher sat down, after talking twenty-two minutes by the clock, a shiver of surprise ran over the whole church. His father had never pounded the desk for less than an hour.

Disappointment, even disgust, was written on every face. The singing was spiritless, and as the people filed out of church and gathered in knots about the door, the old-time head-shaking was resumed, and the comments were many and unfavourable.

“Dat’s what his schoolin’ done fo’ him,” said one.

“It wasn’t nothin’ mo’n a lecter,” was another’s criticism.

“Put him ‘side o’ his father,” said one of the Rev. Abram Dixon’s loyal members, “and bless my soul, de ol’ man would preach all roun’ him, and he ain’t been to no college, neither!”

Robert and his father walked home in silence together. When they were in the house, the old man turned to his son and said:

“Is dat de way dey teach you to preach at college?”

“I followed my instructions as nearly as possible, father.”

“Well, Lawd he’p dey preachin’, den! Why, befo’ I’d ha’ been in dat pulpit five minutes, I’d ha’ had dem people moanin’ an’ hollerin’ all over de church.”

“And would they have lived any more cleanly the next day?”

The old man looked at his son sadly, and shook his head as at one of the unenlightened.

Robert did not preach in his father’s church again before his visit came to a close; but before going he said, “I want you to promise me you’ll come up and visit me, father. I want you to see the work I am trying to do. I don’t say that my way is best or that my work is a higher work, but I do want you to see that I am in earnest.”

“I ain’t doubtin’ you mean well, Robbie,” said his father, “but I guess I’d be a good deal out o’ place up thaih.”

“No, you wouldn’t, father. You come up and see me. Promise me.”

And the old man promised.

It was not, however, until nearly a year later that the Rev. Abram Dixon went up to visit his son’s church. Robert met him at the station, and took him to the little parsonage which the young clergyman’s people had provided for him. It was a very simple place, and an aged woman served the young man as cook and caretaker; but Abram Dixon was astonished at what seemed to him both vainglory and extravagance.

“Ain’t you livin’ kin’ o’ high fo’ yo’ raisin’, Robbie?” he asked.

The young man laughed. “If you’d see how some of the people live here, father, you’d hardly say so.”

Abram looked at the chintz-covered sofa and shook his head at its luxury, but Robert, on coming back after a brief absence, found his father sound asleep upon the comfortable lounge.

On the next day they went out together to see something of the city. By the habit of years, Abram Dixon was an early riser, and his son was like him; so they were abroad somewhat before business was astir in the town. They walked through the commercial portion and down along the wharves and levees. On every side the same sight assailed their eyes: black boys of all ages and sizes, the waifs and strays of the city, lay stretched here and there on the wharves or curled on doorsills, stealing what sleep they could before the relentless day should drive them forth to beg a pittance for subsistence.

“Such as these we try to get into our flock and do something for,” said Robert.

His father looked on sympathetically, and yet hardly with full understanding. There was poverty in his own little village, yes, even squalour, but he had never seen anything just like this. At home almost everyone found some open door, and rare was the wanderer who slept out-of-doors except from choice.

At nine o’clock they went to the police court, and the old minister saw many of his race appear as prisoners, receiving brief attention and long sentences. Finally a boy was arraigned for theft. He was a little, wobegone fellow hardly ten years of age. He was charged with stealing cakes from a bakery. The judge was about to deal with him as quickly as with the others, and Abram’s heart bled for the child, when he saw a negro call the judge’s attention. He turned to find that Robert had left his side. There was a whispered consultation, and then the old preacher heard with joy, “As this is his first offence and a trustworthy person comes forward to take charge of him, sentence upon the prisoner will be suspended.”

Robert came back to his father holding the boy by the hand, and together they made their way from the crowded room.

“I’m so glad! I’m so glad!” said the old man brokenly.

“We often have to do this. We try to save them from the first contact with the prison and all that it means. There is no reformatory for black boys here, and they may not go to the institutions for the white; so for the slightest offence they are sent to jail, where they are placed with the most hardened criminals. When released they are branded forever, and their course is usually downward.”

He spoke in a low voice, that what he said might not reach the ears of the little ragamuffin who trudged by his side.

Abram looked down on the child with a sympathetic heart.

“What made you steal dem cakes?” he asked kindly.

“I was hongry,” was the simple reply.

The old man said no more until he had reached the parsonage, and then when he saw how the little fellow ate and how tenderly his son ministered to him, he murmured to himself, “Feed my lambs”; and then turning to his son, he said, “Robbie, dey’s some’p’n in ‘dis, dey’s some’p’n in it, I tell you.”

That night there was a boy’s class in the lower room of Robert Dixon’s little church. Boys of all sorts and conditions were there, and Abram listened as his son told them the old, sweet stories in the simplest possible manner and talked to them in his cheery, practical way. The old preacher looked into the eyes of the street gamins about him, and he began to wonder. Some of them were fierce, unruly-looking youngsters, inclined to meanness and rowdyism, but one and all, they seemed under the spell of their leader’s voice. At last Robert said, “Boys, this is my father. He’s a preacher, too. I want you to come up and shake hands with him.” Then they crowded round the old man readily and heartily, and when they were outside the church, he heard them pause for a moment, and then three rousing cheers rang out with the vociferated explanation, “Fo’ de minister’s pap!”

Abram held his son’s hand long that night, and looked with tear-dimmed eyes at the boy.

“I didn’t understan’,” he said. “I didn’t understan’.”

“You’ll preach for me Sunday, father?”

“I wouldn’t daih, honey. I wouldn’t daih.”

“Oh, yes, you will, pap.”

He had not used the word for a long time, and at sound of it his father yielded.

It was a strange service that Sunday morning. The son introduced the father, and the father, looking at his son, who seemed so short a time ago unlearned in the ways of the world, gave as his text, “A little child shall lead them.”

He spoke of his own conceit and vainglory, the pride of his age and experience, and then he told of the lesson he had learned. “Why, people,” he said, “I feels like a new convert!”

It was a gentler gospel than he had ever preached before, and in the congregation there were many eyes as wet as his own.

“Robbie,” he said, when the service was over, “I believe I had to come up here to be converted.” And Robbie smiled.

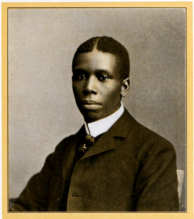

Paul Laurence Dunbar

(1872 – 1906)

Old Abe’s Conversion

From The Heart Of Happy Hollow, a collection of short stories reprinted in 1904 by Dodd, Mead and Company, New York.

Short Story

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive C-D, Archive C-D, Dunbar, Paul Laurence, Dunbar, Paul Laurence, Paul Laurence Dunbar, Paul Laurence Dunbar

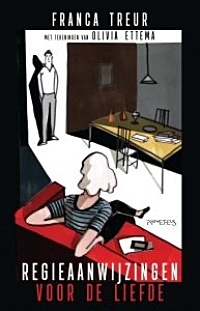

Geliefden Hanna en Loek besluiten samen een scenario te schrijven. Een liefdesverhaal moet het worden, de personages moeten elkaar krijgen. Maar niet op een clichématige manier.

Intussen wordt het steeds benauwder in de huiskamer. Al snel gaan de ramen open en komt de buitenwereld binnen. Aan de ene kant brengt dat lucht, aan de andere kant verleiding.

Intussen wordt het steeds benauwder in de huiskamer. Al snel gaan de ramen open en komt de buitenwereld binnen. Aan de ene kant brengt dat lucht, aan de andere kant verleiding.

Bestaat de veilige cocon nog of heeft de globalisering automatisch ieders wereld groter gemaakt? Welke concessies doet een filmmaker? Hoe flexibel zijn principes? Kun je de redder in nood zijn van je ex?

In vijftig korte hoofdstukken en vijftig tekeningen wordt het moderne leven gefileerd, met bijzondere aandacht voor de liefdesrelatie. Is het moment dat de personages elkaar krijgen het moment waarop Loek en Hanna elkaar verliezen?

Franca Treur debuteerde in 2009 met de roman Dorsvloer vol confetti, waarvan meer dan 150.000 exemplaren werden verkocht. Het was het meest bejubelde literaire debuut in jaren. Het boek won verschillende prijzen en het werd verfilmd. In 2014 verscheen haar tweede roman, De woongroep, en in 2015 het Zeeuwse Boekenweekgeschenk Ik zou maar nergens op rekenen. Daarnaast schrijft ze verhalen, essays en columns voor uiteenlopende media.

Franca Treur

Regieaanwijzingen voor de liefde

Gebonden

216 p.

Druk 1

Verschenen 08-02-19

Uitgever Prometheus

Nederlandse fictie

ISBN 9789044640441

€ 19,99

# new fiction

franca treur

regieaanwijzingen voor de liefde

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Bookstores, Archive S-T, Art & Literature News, Franca Treur

Joni Mitchell: New Critical Readings recognizes the importance and innovativeness of the musician and artist Joni Mitchell and the need for a collection that theorizes her work as musician, composer, cultural commentator and antagonist.

It showcases pieces by established and early career academics from the fields of popular music and literary studies on subjects such as Mitchell’s guitar technique, the politics of aging in her work, and her fractious relationship with feminism.

It showcases pieces by established and early career academics from the fields of popular music and literary studies on subjects such as Mitchell’s guitar technique, the politics of aging in her work, and her fractious relationship with feminism.

The collection features close readings of specific songs, albums, and performances while also paying keen attention to Mitchell’s wider cultural contributions and significance.

About the Author: Ruth Charnock is Senior Lecturer in English at the University of Lincoln, UK. She is the author of Anaïs Nin: Bad Sex, Shame and Contemporary Culture (forthcoming, 2019) and various articles and essays on Joni Mitchell, Marvin Gaye, Anaïs Nin, contemporary American literature, and popular culture.

Joni Mitchell

New Critical Readings

Editor: Ruth Charnock

Published: 24-01-2019

Format: Hardback

Edition: 1st

248 pages

Illustrations: 2 bw illus

Dimensions: 229 x 152 mm

Publisher: Bloomsbury Academic

Language: English

ISBN-10: 1501332090

ISBN-13: 978-1501332098

£86.40

# new books

joni mitchell

new critical readings

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Bookstores, Archive C-D, Archive M-N, Archive M-N, Art & Literature News, Joni Mitchell

Pol Kurucz: Hair Stories

Hair stories is a tale of 12 outlandish hair styles, extensions of 12 eccentric female souls in 12 unconventional scenes.

Pol Kurucz was born with two different names to a French mother in a Hungarian hospital. His childhood hyperactivity was treated with theater, and theater was later treated with finance. By 27 he was a manager by day and a stage director by night. He then went on consecutive journeys to Bahrain and Brazil, to corporate islands and favelas. He has sailed on the shores of the adult industry and of militant feminism and launched a mainstream money making bar loss making in its indie art basement. Then he suddenly died of absurdity. Pol was reborn in 2015 and merged his two names and his contradictory lives into one where absurdity makes sense.

Today he works on eccentric fashion, celebrity and fine art projects in São Paulo and New York. His photos have been featured in over a hundred publications including: Vogue, ELLE, Glamour, Marie Claire, The Guardian, Dazed, Adobe Create, Hunger, Sleek, Nylon, Hi-Fructose, Galore. Pol’s works were exhibited worldwide in 72 galleries and cultural events in 2018 including: Juxtapoz Club House (Art Basel Miami), ArtExpo NYC, Red Dot Miami, Lincoln Center NYC, Shanghai Fashion Week, New York Fashion Week, Superchief Gallery Miami, Lumas Galleries worldwide, Democrart Galleries in Brazil and Pica Photo shows in China.

# more on website pol kurucz

www.polkurucz.com (hair stories: www.polkurucz.com/hairstories)

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Art & Literature News, FDM Art Gallery, Photography, Pol Kurucz, Surrealisme, THEATRE

Quelle force de vérité accorder à la poésie? Apparemment aucune selon Baudelaire.

C’est pourtant lui qui assure le passage décisif vers une poésie qui remet en question ses fondements, son devenir, sa nécessité, une poésie qui exige d’être sans cesse perception à valeur existentielle.

C’est pourtant lui qui assure le passage décisif vers une poésie qui remet en question ses fondements, son devenir, sa nécessité, une poésie qui exige d’être sans cesse perception à valeur existentielle.

La réflexivité poétique qui s’exerce entre apparence et tréfonds de l’homme exacerbe le poétique et le menace. Où, quand, comment et vers quoi se joue le vrai du poème ?

Pourquoi cette oeuvre pose-t-elle les enjeux de la modernité ?

Se débattant contre tout Idéal absolu, la poétique baudelairienne désire la liberté incarnée et douloureuse de l’artiste, de l’humain.

Régine Foloppe, est l’auteur de plusieurs recueils poétiques, notamment : Tributaires du vent (Le Castor Astral, prix Max-Pol Fouchet) et Famines (Belin). Elle a publié des articles et des poèmes dans des revues (PO&SIE, Eidôlon, Friches, Diérèse…). Agrégée de lettres modernes, docteure en littérature française, elle enseigne à l’Université de Montpellier.

Baudelaire et la vérité poétique

Auteur: Régine Foloppe

Editeur : Editions L’Harmattan

Collection : La philosophie en commun

19 février 2019

Format : 15,5 x 24 cm

Broché

464 pages

Langue : Français

ISBN-10: 2343157642

ISBN-13: 978-2343157641

EUR 42,00

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Bookstores, Archive A-B, Archive A-B, Archive E-F, Art & Literature News, Baudelaire, Baudelaire, Charles

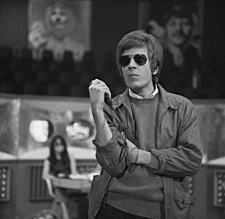

Tilt

Bij de muziek van Scott Walker

I

Slagschaduw van hand met potlood

over de ontcijfering van wat hier klinkt:

links en rechts brandbaar geheimen rollen

in elkaar tot wat een steekspel wordt.

Hij

daar met die neiging, veraf en zo dichtbij

zoals ik hier nu jou reeds weet,

beweegt zich buigend en verlangend

zinvol tasten in. Op zoek naar evenwicht.

II

Deze kluizenaar vermoedt onder kousen sproetjes.

Bezweert binnensmonds nachtmerries en

helt zoals hij denkt in cirkelend

weerkaatsen – luidop maar ongezien,

liefst.

Cimbalen laat hij klateren als water.

Toch hangt van dit geluid zijn leven amper af.

O the Luzerner Zeitung never sold out,

never sold out

III

Over zinnen laat hij zilvergrijze sluiers vallen.

Niemand vraagt waarom. Zo is het dan ook goed.

Zingen is voor deze stem geen afdoend woord:

plofjes adem blijven hangen tussen microfoon en

oren.

Dan zweeft hij tussen fluisteren en fluiten door

op weg naar waterweegbree, webben en de lippen

van een meisje dat met open mond probeert

een mooie ronde o te neuriën

IV

Wereldvreemde man schept eigen logica.

Wie die niet volgen kan mag heel gewoon

een straatje om. Zie je hem dan de pijn niet lijden

van monsters in de nacht, van schaduwen in

regen?

De monnik wist verhalen uit, tegels almaar donkerder

rond de voeten. Hoofdvol galmen wonderen.

In geval van dij, in geval van dij. Hij kust gaten

voor de kogels in geval van dij.

V

Zie hoe het zeil spant. Onder de verse huif

telt hij de rimpels in zijn handen, met die

van zijn vader vol overeenkomsten, net

als de verse verdragen voor toekomst.

Nat

de lakzegel nog. Krullend van heimwee

naar een tijd van jagers stort hij zich

een aanval binnen. Vurig smeedt hij daarin

gulle plannen. Vurig.

Bert Bevers

Verschenen in Gierik & Nieuw Vlaams Tijdschrift, Antwerpen, 1998

In memoriam Scott Walker (born Noel Scott Engel; January 9, 1943 – March 22, 2019)

Photo: Scott Walker – Dutch TV programme Fenklup 1968 – Beeld en Geluid Wiki

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Archive W-X, Art & Literature News, Bevers, Bert, In Memoriam, Scott Walker

De Nasleep

Als dat schôon menske weer lillek is geworden.

Als oe bed zich niet onder oe kont bevindt.

Als het daglicht die hossende Rotterdammer verraadt,

Dan rest alleen nog maar de kater,

maar is uw Carnaval waarschijnlijk geslaagd.

De Kater…

Zou het licht alsjeblieft wat minder hard willen praten?

Ik kan mijn hoofdpijn niet zo goed meer verstaan..

Onias Landveld

Onias Landveld (Paramaribo, 1985) is een verhalenverteller. Hij schrijft, spreekt, dicht en inspireert. Vanaf aug 2017 is hij voor twee jaar de stadsdichter van Tilburg.

Onias Landveld (Paramaribo, 1985) is een verhalenverteller. Hij schrijft, spreekt, dicht en inspireert. Vanaf aug 2017 is hij voor twee jaar de stadsdichter van Tilburg.

Zijn talent deelt hij graag via concepten, workshops en spreek-cursussen. Maar het podium is waar hij het liefst staat. In 1989 ontvluchtte hij samen met zijn familie de Surinaamse burgeroorlog. Na 3 jaar te hebben gewoond in Utrecht, vertrok het gezin weer naar zijn geboorteland. Sinds 1998 woont hij in Tilburg.

Na jaren te hebben rondgedwaald ontdekte hij zijn liefde voor het gesproken woord. In 2015 mocht hij daarvoor de Van Dale Spoken Award voor storytelling ontvangen.

Het heeft hem nog meer gemotiveerd om naar mensen uit te reiken. Altijd zoekende om iemand te raken met een memorabele boodschap, blijft hij met woorden banden smeden. Hij houdt daarvan. Herkenning creëren door een zaadje te planten, gevoed met passie en identificatie.

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: *Concrete + Visual Poetry K-O, Archive K-L, Archive K-L, City Poets / Stadsdichters, Landveld, Onias

Onias Landveld Stadsdichter van Tilburg organiseert op 30 maart, de tweede editie van The Stage. Die avond zal hij met zijn podium te gast zijn bij het Tilt Festival in Theater De Nieuwe Vorst in Tilburg.

Het thema van de avond is “Zij is”, een knik naar de Boekenweek 2019, die ‘Moeder de vrouw’ als onderwerp heeft.

Het thema van de avond is “Zij is”, een knik naar de Boekenweek 2019, die ‘Moeder de vrouw’ als onderwerp heeft.

Met een aantal speciale gasten zal The Stage bezoekers die avond vermaken met poëzie, verhalen en muziek.

De stadsdichter is het podium gestart omdat hij iets wil achterlaten als hij in Augustus dit jaar afzwaait.

Onias Landveld vindt dat woordkunst in een stad als Tilburg een plaats moet blijven hebben. Daarom is hij vorig jaar dit evenement gestart dat zijn vaste plek in de Nwe Vorst heeft.

Op 30 maart staan on Stage: Zeinab El Bouni, Aminata Cairo, LouLou Elisabettie, Lev Avitan, Whitney Muanza Sabina Lukovic en Tessa Gabriëls.

Onias Landveld & The Stage

Tilt Festival in Theater De Nieuwe Vorst

Willem II straat – Tilburg.

Aanvang: 20:45

Einde: 22:45

Kaarten verkrijgbaar via de website van Tilt of de Nieuwe Vorst

# website theater de nieuwe vorst

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: *Concrete + Visual Poetry K-O, - Book Lovers, Archive K-L, Archive K-L, Art & Literature News, City Poets / Stadsdichters, Landveld, Onias, STREET POETRY, THEATRE, Tilt Festival Tilburg

Von Liebe

Am Abend sprach das Meer und flüsterte:

Ihr schönen Mägdelein, erzählt mir leise,

Ich will die Liebe wissen! Redet mir

So von der Liebe, gleich als sollte ich

Dran sterben, so als müsst’ in Ruhe ich

Versinken dran, als könnte sie vorm Sturme

Mich schützen, dass so wütend er nicht mehr

Auf mich sich stürzte! – O! so sprachen da

Die Mägdelein, – Wir wissen wahrlich nicht,

Du armes Meer, ob wir erzählen dürfen;

Denn nimmermehr würdst du in wilder Kraft

Die Schiffe schleudern wollen, und der Felsen

Sorgenumwölbte Stirn mit Schaume peitschen,

Noch wälzen unter jähe, grüne Klippen

Der Sterne Blicken. Glaub’ uns Meer, Du wolltest

So mächtig nimmer sein, so scheu und spröde,

In deinen Schoß und in dein Herz nicht mehr

Die schlafumfangnen Menschenherzen saugen.

Du würdest dann gleich uns den Himmel ansehn,

Und ihn nicht sehen, lächeln, wie der Wind

Vorüberweht, und weinen, weil die Sonne

Aufgeht! Nein! wir werden nichts erzählen!

Carmen Sylva

(1843-1916)

Von Liebe

Gedicht

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Archive S-T, CLASSIC POETRY

`Wat een allemachtig mooie bliksem’, zegt Tijger vol bewondering. Het hele dorp wordt geraakt door vuurpijlen die sissend in de grond slaan.

`Onweer is sprookjesweer’, zegt Thija.

`Onweer is sprookjesweer’, zegt Thija.

Door het raampje van de zolder is het uitzicht op de wereld altijd sprookjesachtig, maar vooral nu, nu de bliksem het dorp wil afbranden en de donkere bossen aan de bovenloop van de Wijer in een witte gloed zet.

In hun bijna geluiddichte schuilplaats op de zolder van de molen horen ze het onweer nauwelijks, maar zien ze wel de bliksem wanneer die als een drietand boven het dorp staat. Hij vonkt langs de bliksemafleider van de kerk. De vlammen spatten van het beeld van Christoffel dat boven op de toren staat en die het dorp bewaakt, met op zijn schouder het kindje Jezus dat al een paar honderd jaar wacht om over de Wijer te worden gedragen.

Thija leest voor uit een van de bijbelboeken die in een doos op de zolder staan. Ze hebben er pas twee gelezen. De rest moet nog.

`Zodra Izebel, de weduwe van koning Achab van Juda, hoorde dat Jehoe, de nieuwe koning van Juda en moordenaar van haar man, haar kwam bezoeken, liet zij haar huis beschilderen, plantte bloemen in haar tuin en nodigde vrouwen in haar huis.’

`Dat zijn veel komma’s in één zin’, zegt Mels.

`Ik kan niet anders lezen dan dat wat er staat’, zegt Thija. Ze leest verder.

`Deze vrouwen waren in de hogere kringen zeer geliefd. Zij verstonden de kunst van het verleiden en maakten daar gebruik van.’

`Hoeren dus’, zegt Tijger. `Net als in de bunker.’

`Op de dag van Jehoes aankomst, verfde Izebel haar ogen zwart, haar lippen rood en haar nagels paars.’ Thija doet een vinger op haar lippen om te voorkomen dat Tijger daar weer opmerkingen over maakt. `Ze maakte haar kapsel in orde, kleedde zich in een jurk van doorschijnende zijde, sierde zich met paarlen, robijnen en blauw glanzende brokken aquamarijn. Daarna ging ze op het met bloemen gestikte kussen voor het venster zitten en wachtte af. Toen ze Jehoe zag naderen, raakte ze zeer opgewonden. “Hoe gaat het de nieuwe koning van Juda?” vroeg ze. “Hoe gaat het de moordenaar van mijn man? Het zal wel goed met hem zijn. De Heer onze God is met hem, want hij heeft het land een dienst bewezen door mijn man Achab te vermoorden.”‘

`Ze had wel lef’, zegt Tijger.

`Toen Jehoe haar hoorde, riep hij woedend tegen zijn soldaten: “Gooi dat kreng het raam uit!” De soldaten grepen Izebel en gooiden haar op de binnenplaats. Daar liet Jehoe haar door de paarden vertrappen. Haar bloed spoot tegen de muur. Wilde honden vraten haar vlees. Haar hersenen werden verzameld door een bedelaar die ermee aan de haal ging.

In de volgende dagen liet Jehoe alle zonen van Achab vermoorden. Achab had zeventig zonen, verwekt bij Izebel, slavinnen en publieke vrouwen. Hij had geen dochters, omdat Izebel nooit een dochter gebaard had. De dochters die Achab verwekt had bij slavinnen en publieke vrouwen, had hij voor de leeuwen laten werpen. Volgens de wetten van het volk waren ze een doorn in het oog van God. De zonen van Achab woonden verspreid over heel Israël, bij oude leermeesters. Ze werden door Jehoes soldaten neergestoken en ontmand. Hun hoofden werden afgehouwen en verpakt in manden naar Jehoe gezonden. Jehoe voerde de hoofden van Achabs zonen aan de wilde dieren. Zo kwam er een einde aan het geslacht van Achab.’

Verbijsterd kijken ze elkaar aan.

`Waarom staat zoiets in de bijbel?’ vraagt Tijger.

`De bijbel is een geschiedenisboek’, zegt Thija.

`Denk je dat dit echt is gebeurd?’

`Natuurlijk. De mensen leefden als beesten.’

`Net als in China?’

`Net als in China.’

`Lees nog maar een verhaal. Met dit weer kunnen we toch niet weg. Maar wel een verhaal dat minder gruwelijk is.’

Thija slaat het boek weer open, maar stokt in haar beweging als de wind de pannen rijtje voor rijtje oplicht en ze roffelend weer op hun plek laat vallen. Een paar pannen vallen kapot. De regen slaat als een waterval op de ruit. Het is echt noodweer.

De bliksem treft de kerk opnieuw. Het kind op de schouder van Christoffel staat in brand.

`Ik hoor dat Jezus “help” roept’, zegt Tijger

`Hierboven horen we niks’, zegt Mels.

`We horen Hem wel’, zegt Thija. `Hij is nog maar een kind. We horen het als Hij angst heeft. Hij roept naar ons. Jezus kan dat. God kan alles.’

`Hij staat echt in brand’, zegt Mels, nauwelijks gelovend wat hij ziet. `De toren brandt.’

Ze zien dat Christoffel wankelt en naar voren helt. Even houdt hij zich vast aan de antenne op zijn rug en draait een halve slag om zijn as. Dan valt hij samen met het kind naar beneden. Hun val wordt gebroken door uitstekende draden en haken, dan tuimelen ze in de afgrond tussen de daken van het dorp.

`Jezus komt thuis bij Zijn Vader op het altaar’, zegt Thija bleek. Ze glijdt van de stapel meelzakken af, knielt neer, haar hoofd gebogen en bidt.

De jongens houden hun adem in. Mels weet dat dit een moment is waarop de wereld kan blijven stilstaan.

Op zolder is het nog stiller dan het al was. Verbijsterd kijken ze naar de vlammen die uit de toren slaan en over het dak van de kerk dansen. In een paar tellen zetten ze het hele gebouw in lichterlaaie.

Ton van Reen: Het diepste blauw (095)

wordt vervolgd

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Het diepste blauw, Archive Q-R, Reen, Ton van

A Day

I’ll tell you how the sun rose, —

A ribbon at a time.

The steeples swam in amethyst,

The news like squirrels ran.

The hills untied their bonnets,

The bobolinks begun.

Then I said softly to myself,

“That must have been the sun!”

But how he set, I know not.

There seemed a purple stile

Which little yellow boys and girls

Were climbing all the while

Till when they reached the other side,

A dominie in gray

Put gently up the evening bars,

And led the flock away.

Emily Dickinson

(1830-1886)

A Day

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive C-D, Dickinson, Emily

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature