Fleurs du Mal Magazine

.jpg)

K ä t h e K o l l w i t z

Die Toten Mahnen uns

Berlin

The street names still reflect old DDR times, before the demolishment of the wall in 1989. The Karl-Liebknecht-Straße runs alongside the Alexanderplatz and connects Prenzlauer Berg to the Museuminsel and Unter den Linden. At the Rosa-Luxembourg-Platz, a few hundred meters to the north, a monument to Herbert Baum and a memorial plaque to Ernst Thälmann commemorate the resistance of the communists against fascism and against the wars that overshadowed life in Europe during the first half of the 20th century. The rise of a working class who lived in miserable conditions dominated social discussions in the early 1900’s. In 1914 a complex combination of imperialism, militarism and strong nationalistic feelings led to the First World War which eventually involved 75 percent of the world’s population and took the lives of 20 million soldiers and civilians. After the war the political situation in Germany remained unstable. The Treaty of Versailles declared Germany responsible for the war, it redefined its territory and Germany was forced to pay enormous war reparations. This treaty caused great bitterness in Germany and was a source of inspiration for both left and right extremism. It eventually led to the rise of fascism and the Second World War. Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxembourg, founders of the Kommunistische Partei Deutschland (KPD), were killed in 1919 by Freikorpsen, right extremist remainders of the German army. Herbert Baum and his resistance group were killed by the Gestapo in 1942 and Ernst Thälmann, Hitlers political opponent during the elections of 1932, was executed in Buchenwald in August 1944, on direct orders from Hitler.

Käthe Kollwitz

Käthe Schmidt was born in Königsberg in 1867 in a family of social democrats that were sensitive to the changes that were taking place in society. Her talent for art was recognised and stimulated by her father. She received lessons in drawing in a private art school in Berlin. Under the influence of her teacher Stauffer-Bern and the work of Max Klinger she decided to focus on black and white drawing, etching and lithography. She married Karl Kollwitz, a friend of the family, in 1891. Karl had decided to dedicate his live to the poor working class and started a doctor’s practice in Prenzlauer Berg in a street that is now called the Käthe-Kollwitz-Straße. They had 2 sons, Hans and Peter. Käthe was deeply moved by the social misery she was confronted with in her husbands practice and the life of the working class became a dominant theme in her work. It was Gerhard Hauptman’s play ‘die Weber’ that inspired her to her first successful series of etchings called ‘Ein Weberaufstand’. Another successful series was ‘Bauernkrieg” for which she received the prestigious ‘Villa Romana’ price. At the age of 50 Käthe had become famous throughout Germany and to the occasion of her birthday, exhibitions of her work were held in Berlin, Bremen and Königsberg.

In October 1914 her son Peter was killed in the trenches of Flanders. To his memory Käthe designed a monument which took her almost 18 years to complete. In Diksmuide-Vladslo, in a landscape covered by hundreds of war cemeteries, her ‘Grieving Parents’ impressively expresses the poignant grief and helplessness of parents who have lost a child. The death of her son had a great impact on her work and war and death became the dominant themes. When Karl Liebknecht was killed in 1919 his family asked Käthe to make a drawing to his memory. In a charcoal drawing she depicts the worker’s farewell to Liebknecht. A final version in woodcut was made 2 years later. Sieben Holzschitte zur Krieg were made in 1920/1923 and her famous poster Nie Wieder Krieg, a consignment by the International Labours Union, in 1924. She was not the only artist that stood up against war but while the artistic protests of for instance George Grosz, Otto Dix or Frans Masereel were primarily aimed at the horrors of the battlefield or the political climate, Käthe Kollwitz’s concern was with the human suffering of those who were left behind.

When the Nazis came to power in 1933, she and her husband signed an urgent appeal to unite the working class and to the formation of a front against Hitler. The SPD and KPD were forbidden by the Nazis and Käthe was removed from her position at the Berlin Art Academy where she was heading the Masterclass of Graphics. Exhibitions of her work were forbidden. Karl was also temporarily disallowed to exercise his practice and their financial situation became precarious until his ban was relieved due to a shortage of skilled physicians. Karl Kollwitz, after a life dedicated to the health of the poor, died in July 1940.

After Karl’s death Käthe suffered from depression and her physical condition was rapidly declining. The house in Berlin where she and Karl had been living since 1891 was bombed in 1943 and Käthe was evacuated to Nordhausen and later to Moritzburg. A few days before the end of the Second World War, in April 1945, Käthe Kollwitz died. She was buried in the family grave in Berlin-Friedrichsfelde at the same cemetery where a memorial monument pays tribute to the socialist heroes Karl Liebknecht, Rosa Luxembourg and Ernst Thälmann.

A mission

Käthe’s importance as an artist cannot be overvalued. Her authentic, expressive depictions of human misery, resulting from the exploitation of human labour, from fascism and war, are timeless, genuine and moving. She was not a politician but an artist with a vocation who found a way to make art that goes straight to the heart.

When you are in Berlin be sure to visit ‘Die Neue Wache’, a building designed by Christian Schinkel, which since the 1960-s is a monument against war and fascism. In the centre of the building, right beneath a circular opening in the ceiling, Käthe Kollwitz’s sculpture Mother and Child is an arresting plea for vigilance against mentalities and attitudes that may again lead to fascism and war.

References:

Ilse Kleberger: Kathe Kollwitz, Eine Biographie

Venues

Neue Wache – Unter den Linden near the Museuminsel

Kathe Kollwitzmuseum Berlin – Fasanenstrasse 24

Käthe Kollwitz: Die Toten mahnen uns – part I

Photos & text: Anton K. Berlin

![]()

Find also on fleursdumal.nl magazine:

Nie Wieder: Wache gegen Faschismus

and

Historia Belgica: Alles voor Vlaanderen

![]()

fleursdumal.nl magazine – magazine for art & literature

to be continued

More in: *War Poetry Archive, Anton K. Photos & Observations, Fascism, Käthe Kollwitz, Sculpture

.jpg)

Street poetry:

Niets in de ruime wereld is zo blij als deze aarde….

Herman Gorter

Photo jef van kempen, Brugge

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Gorter, Herman, Jef van Kempen, Jef van Kempen Photos & Drawings, Street Art

More in: Antony Kok, Dada, De Stijl

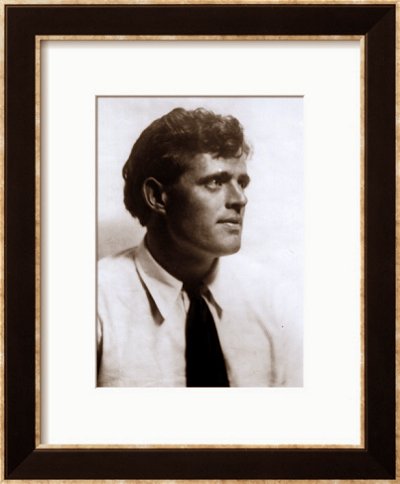

Jack London

(1876-1916)

The Water Baby

I lent a weary ear to old Kohokumu’s interminable chanting of the

deeds and adventures of Maui, the Promethean demi-god of Polynesia

who fished up dry land from ocean depths with hooks made fast to

heaven, who lifted up the sky whereunder previously men had gone on

all-fours, not having space to stand erect, and who made the sun

with its sixteen snared legs stand still and agree thereafter to

traverse the sky more slowly–the sun being evidently a trade

unionist and believing in the six-hour day, while Maui stood for

the open shop and the twelve-hour day.

“Now this,” said Kohokumu, “is from Queen Lililuokalani’s own

family mele:

“Maui became restless and fought the sun

With a noose that he laid.

And winter won the sun,

And summer was won by Maui . . . “

Born in the Islands myself, I knew the Hawaiian myths better than

this old fisherman, although I possessed not his memorization that

enabled him to recite them endless hours.

“And you believe all this?” I demanded in the sweet Hawaiian

tongue.

“It was a long time ago,” he pondered. “I never saw Maui with my

own eyes. But all our old men from all the way back tell us these

things, as I, an old man, tell them to my sons and grandsons, who

will tell them to their sons and grandsons all the way ahead to

come.”

“You believe,” I persisted, “that whopper of Maui roping the sun

like a wild steer, and that other whopper of heaving up the sky

from off the earth?”

“I am of little worth, and am not wise, O Lakana,” my fisherman

made answer. “Yet have I read the Hawaiian Bible the missionaries

translated to us, and there have I read that your Big Man of the

Beginning made the earth, and sky, and sun, and moon, and stars,

and all manner of animals from horses to cockroaches and from

centipedes and mosquitoes to sea lice and jellyfish, and man and

woman, and everything, and all in six days. Why, Maui didn’t do

anything like that much. He didn’t make anything. He just put

things in order, that was all, and it took him a long, long time to

make the improvements. And anyway, it is much easier and more

reasonable to believe the little whopper than the big whopper.”

And what could I reply? He had me on the matter of reasonableness.

Besides, my head ached. And the funny thing, as I admitted it to

myself, was that evolution teaches in no uncertain voice that man

did run on all-fours ere he came to walk upright, that astronomy

states flatly that the speed of the revolution of the earth on its

axis has diminished steadily, thus increasing the length of day,

and that the seismologists accept that all the islands of Hawaii

were elevated from the ocean floor by volcanic action.

Fortunately, I saw a bamboo pole, floating on the surface several

hundred feet away, suddenly up-end and start a very devil’s dance.

This was a diversion from the profitless discussion, and Kohokumu

and I dipped our paddles and raced the little outrigger canoe to

the dancing pole. Kohokumu caught the line that was fast to the

butt of the pole and under-handed it in until a two-foot ukikiki,

battling fiercely to the end, flashed its wet silver in the sun and

began beating a tattoo on the inside bottom of the canoe. Kohokumu

picked up a squirming, slimy squid, with his teeth bit a chunk of

live bait out of it, attached the bait to the hook, and dropped

line and sinker overside. The stick floated flat on the surface of

the water, and the canoe drifted slowly away. With a survey of the

crescent composed of a score of such sticks all lying flat,

Kohokumu wiped his hands on his naked sides and lifted the

wearisome and centuries-old chant of Kuali:

“Oh, the great fish-hook of Maui!

Manai-i-ka-lani–“made fast to the heavens”!

An earth-twisted cord ties the hook,

Engulfed from lofty Kauiki!

Its bait the red-billed Alae,

The bird to Hina sacred!

It sinks far down to Hawaii,

Struggling and in pain dying!

Caught is the land beneath the water,

Floated up, up to the surface,

But Hina hid a wing of the bird

And broke the land beneath the water!

Below was the bait snatched away

And eaten at once by the fishes,

The Ulua of the deep muddy places!

His aged voice was hoarse and scratchy from the drinking of too

much swipes at a funeral the night before, nothing of which

contributed to make me less irritable. My head ached. The sun-

glare on the water made my eyes ache, while I was suffering more

than half a touch of mal de mer from the antic conduct of the

outrigger on the blobby sea. The air was stagnant. In the lee of

Waihee, between the white beach and the roof, no whisper of breeze

eased the still sultriness. I really think I was too miserable to

summon the resolution to give up the fishing and go in to shore.

Lying back with closed eyes, I lost count of time. I even forgot

that Kohokumu was chanting till reminded of it by his ceasing. An

exclamation made me bare my eyes to the stab of the sun. He was

gazing down through the water-glass.

“It’s a big one,” he said, passing me the device and slipping over-

side feet-first into the water.

He went under without splash and ripple, turned over and swam down.

I followed his progress through the water-glass, which is merely an

oblong box a couple of feet long, open at the top, the bottom

sealed water-tight with a sheet of ordinary glass.

Now Kohokumu was a bore, and I was squeamishly out of sorts with

him for his volubleness, but I could not help admiring him as I

watched him go down. Past seventy years of age, lean as a

toothpick, and shrivelled like a mummy, he was doing what few young

athletes of my race would do or could do. It was forty feet to

bottom. There, partly exposed, but mostly hidden under the bulge

of a coral lump, I could discern his objective. His keen eyes had

caught the projecting tentacle of a squid. Even as he swam, the

tentacle was lazily withdrawn, so that there was no sign of the

creature. But the brief exposure of the portion of one tentacle

had advertised its owner as a squid of size.

The pressure at a depth of forty feet is no joke for a young man,

yet it did not seem to inconvenience this oldster. I am certain it

never crossed his mind to be inconvenienced. Unarmed, bare of body

save for a brief malo or loin cloth, he was undeterred by the

formidable creature that constituted his prey. I saw him steady

himself with his right hand on the coral lump, and thrust his left

arm into the hole to the shoulder. Half a minute elapsed, during

which time he seemed to be groping and rooting around with his left

hand. Then tentacle after tentacle, myriad-suckered and wildly

waving, emerged. Laying hold of his arm, they writhed and coiled

about his flesh like so many snakes. With a heave and a jerk

appeared the entire squid, a proper devil-fish or octopus.

But the old man was in no hurry for his natural element, the air

above the water. There, forty feet beneath, wrapped about by an

octopus that measured nine feet across from tentacle-tip to

tentacle-tip and that could well drown the stoutest swimmer, he

coolly and casually did the one thing that gave to him and his

empery over the monster. He shoved his lean, hawk-like face into

the very centre of the slimy, squirming mass, and with his several

ancient fangs bit into the heart and the life of the matter. This

accomplished, he came upward, slowly, as a swimmer should who is

changing atmospheres from the depths. Alongside the canoe, still

in the water and peeling off the grisly clinging thing, the

incorrigible old sinner burst into the pule of triumph which had

been chanted by the countless squid-catching generations before

him:

“O Kanaloa of the taboo nights!

Stand upright on the solid floor!

Stand upon the floor where lies the squid!

Stand up to take the squid of the deep sea!

Rise up, O Kanaloa!

Stir up! Stir up! Let the squid awake!

Let the squid that lies flat awake! Let the squid that lies spread

out . . . “

I closed my eyes and ears, not offering to lend him a hand, secure

in the knowledge that he could climb back unaided into the unstable

craft without the slightest risk of upsetting it.

“A very fine squid,” he crooned. “It is a wahine” (female) “squid.

I shall now sing to you the song of the cowrie shell, the red

cowrie shell that we used as a bait for the squid–“

“You were disgraceful last night at the funeral,” I headed him off.

“I heard all about it. You made much noise. You sang till

everybody was deaf. You insulted the son of the widow. You drank

swipes like a pig. Swipes are not good for your extreme age. Some

day you will wake up dead. You ought to be a wreck to-day–“

“Ha!” he chuckled. “And you, who drank no swipes, who was a babe

unborn when I was already an old man, who went to bed last night

with the sun and the chickens–this day are you a wreck. Explain

me that. My ears are as thirsty to listen as was my throat thirsty

last night. And here to-day, behold, I am, as that Englishman who

came here in his yacht used to say, I am in fine form, in devilish

fine form.”

“I give you up,” I retorted, shrugging my shoulders. “Only one

thing is clear, and that is that the devil doesn’t want you.

Report of your singing has gone before you.”

“No,” he pondered the idea carefully. “It is not that. The devil

will be glad for my coming, for I have some very fine songs for

him, and scandals and old gossips of the high aliis that will make

him scratch his sides. So, let me explain to you the secret of my

birth. The Sea is my mother. I was born in a double-canoe, during

a Kona gale, in the channel of Kahoolawe. From her, the Sea, my

mother, I received my strength. Whenever I return to her arms, as

for a breast-clasp, as I have returned this day, I grow strong

again and immediately. She, to me, is the milk-giver, the life-

source–“

“Shades of Antaeus!” thought I.

“Some day,” old Kohokumu rambled on, “when I am really old, I shall

be reported of men as drowned in the sea. This will be an idle

thought of men. In truth, I shall have returned into the arms of

my mother, there to rest under the heart of her breast until the

second birth of me, when I shall emerge into the sun a flashing

youth of splendour like Maui himself when he was golden young.”

“A queer religion,” I commented.

“When I was younger I muddled my poor head over queerer religions,”

old Kohokumu retorted. “But listen, O Young Wise One, to my

elderly wisdom. This I know: as I grow old I seek less for the

truth from without me, and find more of the truth from within me.

Why have I thought this thought of my return to my mother and of my

rebirth from my mother into the sun? You do not know. I do not

know, save that, without whisper of man’s voice or printed word,

without prompting from otherwhere, this thought has arisen from

within me, from the deeps of me that are as deep as the sea. I am

not a god. I do not make things. Therefore I have not made this

thought. I do not know its father or its mother. It is of old

time before me, and therefore it is true. Man does not make truth.

Man, if he be not blind, only recognizes truth when he sees it. Is

this thought that I have thought a dream?”

“Perhaps it is you that are a dream,” I laughed. “And that I, and

sky, and sea, and the iron-hard land, are dreams, all dreams.”

“I have often thought that,” he assured me soberly. “It may well

be so. Last night I dreamed I was a lark bird, a beautiful singing

lark of the sky like the larks on the upland pastures of Haleakala.

And I flew up, up, toward the sun, singing, singing, as old

Kohokumu never sang. I tell you now that I dreamed I was a lark

bird singing in the sky. But may not I, the real I, be the lark

bird? And may not the telling of it be the dream that I, the lark

bird, am dreaming now? Who are you to tell me ay or no? Dare you

tell me I am not a lark bird asleep and dreaming that I am old

Kohokumu?”

I shrugged my shoulders, and he continued triumphantly:

“And how do you know but what you are old Maui himself asleep and

dreaming that you are John Lakana talking with me in a canoe? And

may you not awake old Maui yourself, and scratch your sides and say

that you had a funny dream in which you dreamed you were a haole?”

“I don’t know,” I admitted. “Besides, you wouldn’t believe me.”

“There is much more in dreams than we know,” he assured me with

great solemnity. “Dreams go deep, all the way down, maybe to

before the beginning. May not old Maui have only dreamed he pulled

Hawaii up from the bottom of the sea? Then would this Hawaii land

be a dream, and you, and I, and the squid there, only parts of

Maui’s dream? And the lark bird too?”

He sighed and let his head sink on his breast.

“And I worry my old head about the secrets undiscoverable,” he

resumed, “until I grow tired and want to forget, and so I drink

swipes, and go fishing, and sing old songs, and dream I am a lark

bird singing in the sky. I like that best of all, and often I

dream it when I have drunk much swipes . . . “

In great dejection of mood he peered down into the lagoon through

the water-glass.

“There will be no more bites for a while,” he announced. “The

fish-sharks are prowling around, and we shall have to wait until

they are gone. And so that the time shall not be heavy, I will

sing you the canoe-hauling song to Lono. You remember:

“Give to me the trunk of the tree, O Lono!

Give me the tree’s main root, O Lono!

Give me the ear of the tree, O Lono!–“

“For the love of mercy, don’t sing!” I cut him short. “I’ve got a

headache, and your singing hurts. You may be in devilish fine form

to-day, but your throat is rotten. I’d rather you talked about

dreams, or told me whoppers.”

“It is too bad that you are sick, and you so young,” he conceded

cheerily. “And I shall not sing any more. I shall tell you

something you do not know and have never heard; something that is

no dream and no whopper, but is what I know to have happened. Not

very long ago there lived here, on the beach beside this very

lagoon, a young boy whose name was Keikiwai, which, as you know,

means Water Baby. He was truly a water baby. His gods were the

sea and fish gods, and he was born with knowledge of the language

of fishes, which the fishes did not know until the sharks found it

out one day when they heard him talk it.

“It happened this way. The word had been brought, and the

commands, by swift runners, that the king was making a progress

around the island, and that on the next day a luau” (feast) “was to

be served him by the dwellers here of Waihee. It was always a

hardship, when the king made a progress, for the few dwellers in

small places to fill his many stomachs with food. For he came

always with his wife and her women, with his priests and sorcerers,

his dancers and flute-players, and hula-singers, and fighting men

and servants, and his high chiefs with their wives, and sorcerers,

and fighting men, and servants.

“Sometimes, in small places like Waihee, the path of his journey

was marked afterward by leanness and famine. But a king must be

fed, and it is not good to anger a king. So, like warning in

advance of disaster, Waihee heard of his coming, and all food-

getters of field and pond and mountain and sea were busied with

getting food for the feast. And behold, everything was got, from

the choicest of royal taro to sugar-cane joints for the roasting,

from opihis to limu, from fowl to wild pig and poi-fed puppies–

everything save one thing. The fishermen failed to get lobsters.

“Now be it known that the king’s favourite food was lobster. He

esteemed it above all kai-kai” (food), “and his runners had made

special mention of it. And there were no lobsters, and it is not

good to anger a king in the belly of him. Too many sharks had come

inside the reef. That was the trouble. A young girl and an old

man had been eaten by them. And of the young men who dared dive

for lobsters, one was eaten, and one lost an arm, and another lost

one hand and one foot.

“But there was Keikiwai, the Water Baby, only eleven years old, but

half fish himself and talking the language of fishes. To his

father the head men came, begging him to send the Water Baby to get

lobsters to fill the king’s belly and divert his anger.

“Now this what happened was known and observed. For the fishermen,

and their women, and the taro-growers and the bird-catchers, and

the head men, and all Waihee, came down and stood back from the

edge of the rock where the Water Baby stood and looked down at the

lobsters far beneath on the bottom.

“And a shark, looking up with its cat’s eyes, observed him, and

sent out the shark-call of ‘fresh meat’ to assemble all the sharks

in the lagoon. For the sharks work thus together, which is why

they are strong. And the sharks answered the call till there were

forty of them, long ones and short ones and lean ones and round

ones, forty of them by count; and they talked to one another,

saying: ‘Look at that titbit of a child, that morsel delicious of

human-flesh sweetness without the salt of the sea in it, of which

salt we have too much, savoury and good to eat, melting to delight

under our hearts as our bellies embrace it and extract from it its

sweet.’

“Much more they said, saying: ‘He has come for the lobsters. When

he dives in he is for one of us. Not like the old man we ate

yesterday, tough to dryness with age, nor like the young men whose

members were too hard-muscled, but tender, so tender that he will

melt in our gullets ere our bellies receive him. When he dives in,

we will all rush for him, and the lucky one of us will get him,

and, gulp, he will be gone, one bite and one swallow, into the

belly of the luckiest one of us.’

“And Keikiwai, the Water Baby, heard the conspiracy, knowing the

shark language; and he addressed a prayer, in the shark language,

to the shark god Moku-halii, and the sharks heard and waved their

tails to one another and winked their cat’s eyes in token that they

understood his talk. And then he said: ‘I shall now dive for a

lobster for the king. And no hurt shall befall me, because the

shark with the shortest tail is my friend and will protect me.

“And, so saying, he picked up a chunk of lava-rock and tossed it

into the water, with a big splash, twenty feet to one side. The

forty sharks rushed for the splash, while he dived, and by the time

they discovered they had missed him, he had gone to bottom and come

back and climbed out, within his hand a fat lobster, a wahine

lobster, full of eggs, for the king.

“‘Ha!’ said the sharks, very angry. ‘There is among us a traitor.

The titbit of a child, the morsel of sweetness, has spoken, and has

exposed the one among us who has saved him. Let us now measure the

lengths of our tails!

“Which they did, in a long row, side by side, the shorter-tailed

ones cheating and stretching to gain length on themselves, the

longer-tailed ones cheating and stretching in order not to be out-

cheated and out-stretched. They were very angry with the one with

the shortest tail, and him they rushed upon from every side and

devoured till nothing was left of him.

“Again they listened while they waited for the Water Baby to dive

in. And again the Water Baby made his prayer in the shark language

to Moku-halii, and said: ‘The shark with the shortest tail is my

friend and will protect me.’ And again the Water Baby tossed in a

chunk of lava, this time twenty feet away off to the other side.

The sharks rushed for the splash, and in their haste ran into one

another, and splashed with their tails till the water was all foam,

and they could see nothing, each thinking some other was swallowing

the titbit. And the Water Baby came up and climbed out with

another fat lobster for the king.

“And the thirty-nine sharks measured tails, devoting the one with

the shortest tail, so that there were only thirty-eight sharks.

And the Water Baby continued to do what I have said, and the sharks

to do what I have told you, while for each shark that was eaten by

his brothers there was another fat lobster laid on the rock for the

king. Of course, there was much quarrelling and argument among the

sharks when it came to measuring tails; but in the end it worked

out in rightness and justice, for, when only two sharks were left,

they were the two biggest of the original forty.

“And the Water Baby again claimed the shark with the shortest tail

was his friend, fooled the two sharks with another lava-chunk, and

brought up another lobster. The two sharks each claimed the other

had the shorter tail, and each fought to eat the other, and the one

with the longer tail won–“

“Hold, O Kohokumu!” I interrupted. “Remember that that shark had

already–“

“I know just what you are going to say,” he snatched his recital

back from me. “And you are right. It took him so long to eat the

thirty-ninth shark, for inside the thirty-ninth shark were already

the nineteen other sharks he had eaten, and inside the fortieth

shark were already the nineteen other sharks he had eaten, and he

did not have the appetite he had started with. But do not forget

he was a very big shark to begin with.

“It took him so long to eat the other shark, and the nineteen

sharks inside the other shark, that he was still eating when

darkness fell, and the people of Waihee went away home with all the

lobsters for the king. And didn’t they find the last shark on the

beach next morning dead, and burst wide open with all he had

eaten?”

Kohokumu fetched a full stop and held my eyes with his own shrewd

ones.

“Hold, O Lakana!” he checked the speech that rushed to my tongue.

“I know what next you would say. You would say that with my own

eyes I did not see this, and therefore that I do not know what I

have been telling you. But I do know, and I can prove it. My

father’s father knew the grandson of the Water Baby’s father’s

uncle. Also, there, on the rocky point to which I point my finger

now, is where the Water Baby stood and dived. I have dived for

lobsters there myself. It is a great place for lobsters. Also,

and often, have I seen sharks there. And there, on the bottom, as

I should know, for I have seen and counted them, are the thirty-

nine lava-rocks thrown in by the Water Baby as I have described.”

“But–” I began.

“Ha!” he baffled me. “Look! While we have talked the fish have

begun again to bite.”

He pointed to three of the bamboo poles erect and devil-dancing in

token that fish were hooked and struggling on the lines beneath.

As he bent to his paddle, he muttered, for my benefit:

“Of course I know. The thirty-nine lava rocks are still there.

You can count them any day for yourself. Of course I know, and I

know for a fact.”

GLEN ELLEN.

October 2, 1916.

From Jack London: ON THE MAKALOA MAT/ISLAND TALES

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive K-L, London, Jack

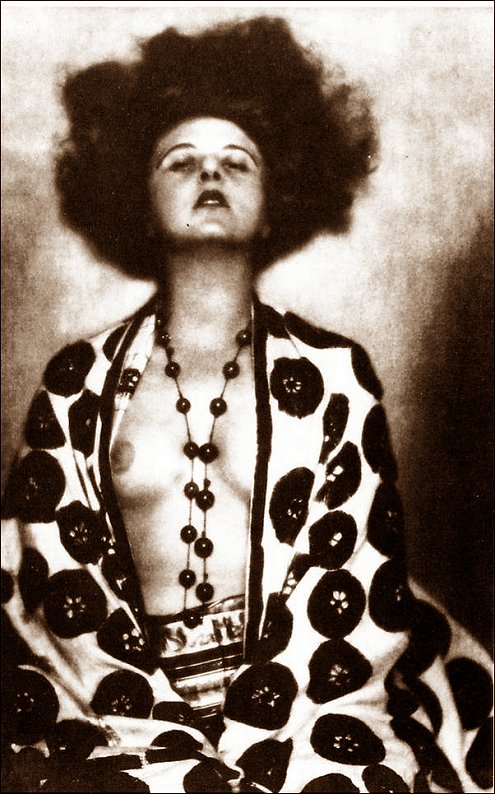

ANITA BERBER

(1899-1928)

O r c h i d e e n

Ich kam in einen Garten

Der Garten war voll von Orchideen

So voll so voll und schwer

Es blühte und lebte und bebte

Ich kam nicht durch die süßen Verschlingungen

Ich liebe sie so wahnsinnig

Für mich sind sie wie Frauen und Knaben –

Ich küsste und koste jede bis zum Schluss

Alle alle starben an meinen roten Lippen

an meinen Händen

an meiner Geschlechtslosigkeit

Die doch alle Geschlechter in sich hat

Ich bin blass wie Mondsilber

Anita Berber Gedichte

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Anita Berber, Anita Berber, Berber, Anita, DANCE & PERFORMANCE

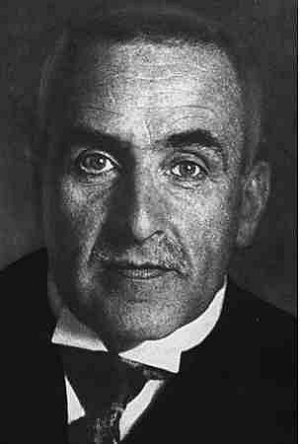

Frank Wedekind

(1864-1918)

Der Gefangene

Oftmals hab ich nachts im Bette

Schon gegrübelt hin und her,

Was es denn geschadet hätte,

Wenn mein Ich ein andrer wär.

Höhnisch raunten meine Zweifel

Mir die tolle Antwort zu:

Nichts geschadet, dummer Teufel,

Denn der andre wärest du!

Hilflos wälzt ich mich im Bette

Und entrang mir dies Gedicht,

Rasselnd mit der Sklavenkette,

Die kein Denker je zerbricht.

Frank Wedekind poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive W-X, Frank Wedekind

Camera obscura: Portrait

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Camera Obscura

Anne Boleyn

(1507?-1536)

Defiled is my name full sore

Through cruel spite and false report,

That I may say for evermore,

Farewell, my joy! Adieu comfort!

For wrongfully ye judge of me

Unto my fame a mortal wound,

Say what ye list, it will not be,

Ye seek for that can not be found.

Anne Boleyn poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Anne Boleyn, Archive A-B

![]()

Babelmatrix Translation Project

György Konrád

A látogató (Hungarian)

7

Ha íróasztalomnál ülve tenyeremet homlokomra szorítom, mert mögötte, ahogy beléptem a hivatal kapuján, jobb és bal felöl zakatolni kezdett egy-egy elnémíthatatlan, törpe írógép, szakadozott, kellemetlen mondatroncsokat dobálva figyelmem napról napra zsugorodó mezejére,

ha idegeimben elindul néhány korty pálinka, mint egy porlepte, kivénhedt televíziós készülékben a villanyáram, s ettöl egész zsibbadt agyvelöm sercegni kezd, s megszabadulva a türhetetlen kopácsolástól, elsötétített recehártyámon zajlani kezdenek a képek, várakozásteljes, gyermekkori torlódással elöbb, bicegö, vonalas szerkezetekkel utóbb,

ha nem szól senki, nem eröszakoskodik a telefon, nem hörög a fütötest, nem hív senkit sehová a hangosbemondó, nem dörren percenként a felvonófülke csapóajtaja, nem kaparásznak ablakpárkányomon az örökké hasmenéses galambok, és nem csoszognak ablakom alatt a veszendö lábbelik tétova és leselkedö gazdáikkal az üveg mögött,

ha kiejtettem lomkamrához mindinkább hasonlító emlékezetemböl az öklüket rázó hadügyminiszterek, a puszta leheletnél is kevesebbet mondó illetékes szóvivök, a bírósági üvegkalickában bóbiskoló tömeggyilkosok, a halkan kicserélt mesterkémek, a barátaikat felkötteto”, újdonsült népvezérek, az emberevö istenkirályok, a szoborleleplezö, új kenyeret szego”, hídavató, díszszázad elött ellépö, virágcsokros kislányokat homlokon csókoló, üdvözlö táviratokat küldö és rendjeleket osztogató, katódsugarak hullámain minden szobába bemosolygó buboréknagyságok tolakodó nevét,

ha elözö este feleségemet átkarolva csendben végigjárjuk szokott sétautunkat a hegyoldalon, ha a lakbért, villany- és telefonszámlát már kifizettem, s maradt pénz tejre, húsra, almára, kávéra, dohányra és borra is, ha éjszaka sikerült hosszan és ájultan aludnom, majd ha a keltöóra robbanásától a mosdó elé lökve idöben elvégeztem a fölkelés elhomályosuló gondolatokkal központozott szertartásait, s a kávé friss gözével fejemben, az autóbusz ablakánál ülöhelyet kapva becsukódhattam felebarátaim füst-, esö- és konyhaszagú kabátjai között,

akkor, istenem, akkor is csak olyan lesz ez a nap, mint a többi.

8

Kezd felerösödni az elötérben várakozó ügyfelek lármája. Rugdossák az állványos hamutartót, nyikorgatják a fütötest kallantyúját, köhögnek, harákolnak, jövetelük várható eredményét latolgatják. Nincs nap, hogy el ne jönnének, ha vasárnap is lehetne panaszkodni, vasárnap is panaszkodnának. Az arcok váltakoznak, a sérelmek alig. Jobb híján valami görbe élvezetet várnak attól, hogy egy hivatalnok jegyzökönyvben örökíti meg panaszaikat. Milyen természetes, hogy idejönnek és kiszolgáltatják magukat. Míg szét nem bontja az ido” a hivatal épületét, az ügyfél idejön, benépesíti a hivatalnok szabályos déleöttjeit, s gondjaival elszórakoztatja. Mivel gondja van: meztelen. Mire beér a fogadószobába, biztonságát lemorzsolja a várakozás, a szorultság, a büntudat. A csupasz, szürke falak, az egyforma, sötét hivatali bútorok, a fakó arcú elöadók, a szomszédos helyiségekböl átszürödö írógépcsattogás, az ajtón kívül várakozók duruzsolása önmagával szembesíti az ügyfelet. A hivatalnoknak jelen esetben nincsen gondja. Higgadtan, tartózkodón, megértö és irgalmatlan fensöbbségébe zárkózva, színe elé bocsátja az ügyfelet, ezt az izgatott és esendö lényt, aki akar valamit, vagy fél valamitöl. Ha a hivatalnoknak is gondja lenne, nyomban ügyféllé lágyulna, valahol, egy másik hivatalban, az övéhez hasonló íróasztalok túlsó oldalán. A szabványméretü íróasztal nem szélesebb egy méternél. De az a két ember, aki elötte és mögötte ül, most éppoly messze van egymástól, mint a júdásszem két oldalán a fogoly és a foglár. Ezt az asztalt nem lehet megkerülni, ezen az asztalon nem lehet áthajolni, ott magasodik két fölismerhetetlen arcú ember között, semlegesen, de a szerepeket csakúgy elkülönítve, mint a deres vagy a nyaktiló.

Az ügyfél feszengve áll, míg hellyel nem kínálják, hosszan forgatja ujjai közt cigarettáját, és engedélyt kér, hogy rágyújthasson. Verejtékmirigyei böszülten termelnek, lehelete megáporodik, homlokát pirosság futja el, s rövid kertelés után olyan vallomásokat tesz, amelyekre barátok között is ritkán kerül sor. Cserevallomás nem szakítja félbe, övé a szó. Gyónni pedig kopár hivatali bútorok között, egy némán cigarettázó tisztviselö elött is lehet. Elég indíttatás elörehajló figyelme meg két-három szakavatott kérdés. Kérdezni úgy kell, ahogy a sebésznek vágni, ahogy az anyának gyermeke fájó hasára tenni a kezét. A hivatalnok valószínu”tlen részleteket firtat nyugodt, köznapi hangon, néha pedig megjegyzi: „kellemetlen… nem volt szép töle… hogyne, megértem… ez csakugyan hiba…” Mellesleg igyekszik elhárítani magától az óvatlan részvét kelepcéit, szándéktalanul: az elötte vetközö gyöngeség mérsékelt rosszallásával, beidegzett hitetlenséggel, az átlagos eset unalmával, a szélso” példák rovartani méltánylásával, az erkölcsi készségek és készületlenségek szabályos ismétlödéseinek elörelátásával. Az ügyfél eltörpül ügye mögött. A hivatalnok is felszívódik hatásköre mögött. Az ügy pedig három, esetleg négy példányban dübörög az írógépen, sorvégeken kurtán csilingel, míg elkövetkeznek a végso”, a föloldozó szavak: „Egyebet elöadni nem kíván, a jegyzökönyvet helybenhagyólag aláírja. Kelt mint fent.”

Mintha öklömnyi sárrögöket nyelnék, sem megemészteni, sem kihányni nem tudom, gondoltam pályám kezdetén. Tíz év alatt mintegy harmincezerszer mondhattam: „Foglaljon helyet; kérem.” A kollégákon, tanúkon, feljelentökön, kíváncsiskodó újságírókon meg néhány szelíd elmebetegen kívül, a többség szorultságában keresett fel.

Nagyobb részük baja tömör volt, kisugárzó és gyógyíthatatlan, így éreztem ebben a szobában, ahol az efféle szólam: „tessék elhinni, nagyon fáj”, „nem bírom tovább”, „belepusztulok”, mindennapos és helyénvaló, mint hullámvasúton a sikongatás. Az én kérdezo”sködésem meg inkább csak arra a sebészi eljárásra emlékeztet, melynek során az orvos összevarrjöa frissen fölvágott sebet, anélkül hogy hozzányúlt volna a daganathoz.

Minden intézményhez hozzátartozik egy lelkiállapot. Ügyfelem a cirkuszban nevet, a gözfürdöben révedezik, a villamoson elbambul, bokszmeccsen harcias, temetöben pacifista s így tovább. Ebbe a szobába elhozza szenvedésének néhány mintáját, fiára, lányára átörökített kudarcait. Lehet, hogy az a pillanatkép, amit én látok éveinek omlékony vakondjárataiból, megtéveszto”. Tegnap megrúgták, ma már engesztelik, holnap simogatják, és én csak a tegnapot látom. A pillanatképnek, bár óvatosan, mégis hitelt adok. Ha öt nem is, körülményeit megismerem. Baklövéseinek ábrája pedig – a többiekére ráfényképezödve – elárulja azt, ami belo”le kiváltságosan az övé, s kiszámíthatatlan része szerény ráadás csupán a kiszámíthatóhoz. Körülményei, mit mondjak, szorosak. Helytétéröl, szokásairól, korábbi balfogásairól mint állami tisztviselo”, hírt kapok; ha sokat nem is, annyit mindenesetre tudhatok róla, hogy mozgásterét felbecsüljem. Mindez éppenséggel nem ü, csak a burok, amelyben fészkelödhet. Kelletlenül azonosítom ügyfelemet e sok limlommal, sajnálom, hogy kötöttségeiben csak ennyire tudott megvalósulni. Már az is dicséretes lenne, ha kissé bonyolultabb rendszert alkotna környezetével, ha változatosabb szabályosságoknak hódolna. Rendszerének bonyolultsági foka azonban lehangolóan szerény, jövedelme csekély, térbeli foglalata kopár, látása homályos, terhei súlyosak. Mozgási szabadsága az átlagosnál is kisebb, indulatai szervezetlenek, súrlódnak, olykor karamboloznak. Ilyenkor cso”dület támad körülötte, s színre lép a hatóság, hogy a forgalom rendjét biztosítsa. Kiskorú gyermekeinek, valamint az államérdeknek védelmére fölhatalmazva, az a dolgom, hogy összebékítsem körülményeivel, s hivatalból ellenezzem hajlandóságát a szenvedésre. Teszem, amire a törvény és tapogatózó ítéletem feljogosít, s megbabonázva nézem, milyen ronccsá, semmivé zúzódik, ahogy a rend lecsap rá.

Publisher: A látogató, p. 17-23., Magveto” Kiadó, Budapest, 1988

György Konrád

The case worker (English)

If I sit at my desk with my head in my hands, it is because the moment I entered the office a thousand pygmy typewriters began to clatter right and left, hurling incongruous phrases into the ever shrinking field of my attention…

if a few drops of brandy make my nerves pulsate as an electric current awakens a dusty old television set to life, my benumbed brain starts crackling and, liberated from the insufferable hammering, engenders images that, at first diffuse, then organized, parade across my hesitant retina…

if nobody says anything; if the telephone keeps quiet, the radiator doesn’t hiss, the loudspeaker doesn’t bark, the door of the elevator doesn’t clatter every minute, and diarrheal pigeons are not scratching at my windowsill; if the worn-down shoes of uncertain, nosy people are not shuffling past my window…

if from my memory that is becoming more and more like a junk pile I expel table-pounding ministers of war, official spokesmen who communicate nothing, mass murderers dozing in bulletproof docks, double agents exchanged on the q.t., newly spawned popular dictators who string up their friends, cannibalistic monarchs by divine right, the season’s celebrities whose electronic smile invades every room, who unveil statues, taste the new wine, inaugurate highways, inspect guards of honor, kiss babies, send telegrams of congratulation, and present medals and gold watches…

if my wife and I have gone for our usual quiet walk on the hillside the night before; if the rent, electric, and telephone bills have been paid and there’s still enough money for milk, meat, fruit, coffee, tobacco, and wine…

if after a good night’s sleep, propelled to the washbasin by the exploding alarm, I have successfully completed the befuddled ritual of getting up; if with the aroma of fresh coffee in my head I have managed, on taking the bus, to find a seat by the window and collect my thoughts amid overcoats smelling of tobacco, rain, dishwater, and dry toast…

… then, even then, this day will be still pretty much the same as every other day.

My clients in the waiting room are making more and more of a hubbub. They kick the standing ashtray, fiddle with the squeaking radiator valve, cough, clear their throats, speculate on the outcome of their visits. Every day without fail they are here; if they could, they’d come on Sunday as well. The faces change, the grievances are always pretty much the same. If nothing else, they derive a certain perverse pleasure in having their complaints officially recorded. How natural that they should come and demand attention. As long as this building stands, clients will come here to take up some official’s morning hours and entertain him with their problems. Since a client has worries, he is defenseless. By the time he reaches the inner office, the wait, his plight, and his sense of guilt have shaken his confidence. The bare gray walls, the dreary regulation furniture, the colorless faces of the office staff, the clack of type- writers filtering through from neighboring offices, and the mutterings of those behind him in the line bring him face to face with himself. The official, on the other hand, has nothing to worry about. Impassive, draped in condescending superiority, he has the client-that frail, flustered being who wants something or is afraid of something-admitted. If the official had cares of his own, he himself would degenerate into a client in some other office, on the other side of just such a desk. The standard desk is no more than a yard deep. But the two persons facing each other across it are as far apart as convict and jailer on opposite sides of the bars. There is no way around or across this desk; it stands between two faces, two enigmas, inert, but apportioning the roles as unmistakably as a whipping post or a guillotine.

Ill at ease, the client remains standing until offered a chair; nervously he fiddles with a cigarette, and eventually asks for permission to light it. His sweat glands operate at full capacity, his breath goes sour, the blood rises to his forehead. Finally, after beating about the bush for a while, he delivers himself of confessions that close friends would hesitate to make to each other. Since there are no counterconfessions to distract him, the floor is all his. Even a civil servant, silently smoking amid bleak official furniture, can serve as confessor. He leans forward attentively and asks two or three expert questions; that suffices to release the flood. The questioner must proceed as delicately as a surgeon probing with his scalpel or a mother resting a soothing hand on her child’s bellyache. In a calm, workaday voice he dwells on unlikely details, remarking from time to time: „Unfortunate… that wasn’t nice of him… yes, I see… that was bad…” At the same time he tries to avoid the pitfalls of unguarded commiseration, expressing mild disapproval of the client’s weakness, but also evincing professional skepticism. In the presence of routine cases he may show a certain boredom, while extreme cases arouse his scientific enthusiasm. The client vanishes behind his case, the official behind his function. Meanwhile, the case in three of four copies thunders over the typewriter, which tinkles at the end of each line and finally delivers itself of the formula: „The witness wishes to add nothing further to his statement and signs it herewith. Date as above.”

At the beginning of my career, I thought: It’s like swallowing fistfuls of mud; I can neither digest it nor vomit it up. In the last ten years I must have said, „Have a seat, please,” thirty thousand times. Apart from colleagues, witnesses, informers, prying newspapermen, and a few inoffensive mental cases, it was distress that drove most of them to my desk. In most instances their anguish was massive, tentacular, and incurable; it weighed on me in this room where people cry, „Believe me, it hurts,” „I can’t go on,” and „It’s killing me,” as easily as they would scream on a roller coaster. On the whole, my interrogations make me think of a surgeon who sews up his incision without removing the tumor.

Every institution makes for a specific state of mind. At the circus my client laughs, at the public baths he daydreams, on the streetcar he stares into space, at a boxing match he is aggressive, in the cemetery subdued, and so on. To this room he brings a few samples of his sufferings and of frustrations that he has handed on to his sons and daughters. Quite possibly the image I get – the barest tip of the fragile molehill of his life – is deceptive. Yesterday he was kicked, today he gets apologies and tomorrow he may even come in for a caress or two, but all I see is his past. Nevertheless, I trust the momentary image, though with some caution. I may not know the man himself, but I know his circumstances. A diagram of his blunders, superimposed on those of other people, brings out what is specific to him, showing that what is unpredictable in him is infinitesimal compared to what is predictable. His circumstances are, let us say, straitened. In my official capacity I am informed of his job, habits, and previous blunders; this allows me to estimate how much freedom of action he has. Of course, what I see isn’t the man himself, but only the envelope in which he moves about. Yet, reluctantly, I identify my client with all these odds and ends, and feel sorry for him because so many obstacles have impeded his development. It would be commendable if his relations with his environment were somewhat more complex, if the rules he chose to live by were a little less conventional. But his system is depressingly lacking in complexity, his income wretched, his physical surroundings dreary, his vision blurred, his burden heavy. His freedom of action is below average, his drives, which are without direction, conflict and sometimes collide head on. When this happens, the traffic jams up and official intervention is needed to start it moving again. Since my job is to protect children and safeguard the interests of the state, the most I can do is reconcile him with his circumstances and oppose his propensity for suffering. I do what the law and my fumbling judgment permit; then I look on, mesmerized, as the system crushes him.

Aston, Paul

Source of the quotation: The case worker, p. 28-33., Budapest, Noran, 1998

György Konrád

De bezoeker (Dutch)

7

Als ik aan mijn bureau zit en mijn hand tegen mijn voorhoofd druk, want daarachter begon dadelijk nadat ik de deur van de Dienst achter me had dichtgedaan van rechts en links een niet tot zwijgen te brengen mini-schrijfmachine te ratelen en het dag na dag verder inkrimpende terrein van mijn aandacht met uit hun verband gerukte, onaangename zinsbrokken te bombarderen; als een paar slokken drank als een lichtstroom in een stokoud en stoffig televisietoestel irisdiafragma’s openen in mijn zenuwvaten en mijn geheel verdoofde brein begint te knetteren en, bevrijd van het ondraaglijke gehamer, op mijn duistere netvlies het flikkeren van beelden inzet, aanvankelijk met een even grote verwachtingen wekkende toevloed als toen ik nog een kind was, verlopend in verspringende lineaire structuren, dan,

als niemand wat zegt, de telefoon niet met een krankzinnige hardnekkigheid rinkelt, de radiator niet borrelt, de luidspreker niemand oproept, als de deur van de lift niet elke minuut dreunend dichtslaat, op mijn vensterbank niet de eeuwig door buikloop geplaagde duiven scharrelen en geen krakend schoeisel tezamen met zijn treuzelende en talmende eigenaren langs mijn deurraampje sloft,

als ik uit mijn steeds meer van een rommelkamer wegkrijgende geheugen de opdringerige namen van vuistenballende defensieministers, de minder dan niets zeggende officiële woordvoerders, de in een glazen kooi voor de rechtbank soezende massamoordenaars, de in alle stilte uitgewisselde meesterspionnen, de kersverse, hun oude vrienden uit de weg ruimende volksleiders, de mensenetende koningen bij de gratie Gods, de standbeelden onthullende, het eerste brood van de nieuwe oogst aansnijdende, bruggen inwijdende, erewachten inspecterende, het voorhoofd van bloemenzwaaiende meisjes kussende, gelukstelegrammen versturende en lintjes uitdelende, op de golven van de kathodestralen in alle huiskamers glimlachend verschijnende eendagsberoemdheden heb gebannen,

als ik samen met mijn vrouw aan het begin van de vorige avond zwijgend de gebruikelijke wandeling langs de berghelling heb gemaakt, als ik de huur, de elektriciteits- en telefoonrekening heb voldaan en er geld voor melk, appels, koffie, tabak en wijn is overgebleven, als het me gelukt is de nacht slapend als een blok door te komen, als ik, door de explosie van de wekker naar de wastafel geslingerd, op tijd de door de doezelige gedachten bij het ontwaken geïnterpuncteerde ceremoniën heb verricht en met de geur van verse koffie nog in mijn neus een zitplaats bij het raampje van de bus heb weten te veroveren en mij tussen de naar rook, regen en keukens ruikende jassen van mijn medemensen heb genesteld,

dan zal, mijn god, ook deze dag niet anders zijn dan alle andere.

8

Het kabaal dat de cliënten in de wachtkamer maken wordt erger. Ze stoten tegen de rookstandaard, morrelen aan de regelknop van de verwarming, hoesten, schrapen hun keel, discussiëren over het verwachte resultaat van hun komst. Geen dag gaat er voorbij zonder dat ze komen; als ze ook ‘s zondags met hun klachten terecht zouden kunnen, zouden ze het niet laten. De gezichten wisselen, de klachten nauwelijks. Bij gebrek aan iets beters vinden de mensen een soort pervers genoegen in de gedachte dat een ambtenaar uit hun klachten een proces-verbaal fabriceert. Wat is het een vanzelfsprekende zaak om hier naar toe te komen en je uit te leveren. Zolang de tand des tijds het gebouw van de Sociale Dienst niet aantast zullen de cliënten blijven toestromen, de vaste ochtenduren van de ambtenaren vullen en hen deelgenoot maken van hun zorgen. Omdat ze zorgen hebben, zijn ze naakt. Als ze de spreekkamer binnenkomen hebben het wachten, de nood en hun schuldbewustzijn hun zelfverzekerdheid gesloopt. De kale grauwe wanden, de eenvormige donkere kantoormeubelen, de ambtenaren met hun vale gelaatskleur, het vaag uit de aangrenzende vertrekken binnendringende schrijfmachinegeratel, het gemurmel van degenen die voor de deur wachten confronteren de cliënt met zichzelf. De ambtenaar heeft in het onderhavige geval geen zorgen. Gelaten, terughoudend, gehuld in zijn begrijpende en genadeloze superioriteit laat hij de cliënt binnenkomen, dit van de zenuwkoorts trillende, beklagenswaardige wezen dat iets wil of voor iets bang is. Zou ook de ambtenaar door zorgen worden gekweld, dan zou hij in een handomdraai zelf in een gedweeë cliënt veranderen, ergens anders, bij een andere instantie. Het in standaardafmetingen vervaardigde schrijfbureau is niet breder dan een meter. Maar tussen de een die ervoor en de ander die erachter zit, bevindt zich precies zo’n grote afstand als tussen een arrestant en een bewaarder aan weerskanten van het kijkgaatje. Je kunt niet om dit bureau heenlopen, je kunt je er niet overheen buigen, het rijst torenhoog tussen deze twee mensen met hun onherkenbaar geworden gezichten op; het is neutraal, maar het verdeelt de rollen even scherp als een pijnbank of een valbijl.

De cliënt blijft besluiteloos staan totdat hem een stoel wordt aangeboden, lange tijd draait hij een sigaret tussen zijn vingers rond voordat hij vraagt of hij hem mag opsteken. Zijn zweetklieren zijn door een tomeloze produktiewoede aangegrepen, zijn adem ruikt plotseling bedorven, zijn gezicht kleurt zich rood, en na even over wat anders te hebben gepraat legt hij bekentenissen af die zelfs boezemvrienden elkaar zelden of nooit doen. Hij wordt door geen enkele tegenbekentenis onderbroken, het woord is aan hem. Biechten kun je ook temidden van armoedige kantoormeubelen, ten overstaan van een zwijgend rokende ambtenaar. Om de lawine aan het rollen te brengen is een tot luisteren bereide aandacht voldoende, misschien nog aangevuld met twee of drie geroutineerde vragen. Vragen moet je ofwel als een chirurg die een ontleedmes hanteert, ofwel als een moeder die haar hand op de zere buik van haar kind legt. Op kalme en alledaagse toon gaat de ambtenaar keer op keer de irreële details te lijf, van tijd tot tijd zegt hij: ’Wat naar… dat was beslist niet mooi van hem… ja ja, ik begrijp het… dat komt werkelijk niet te pas…’ Ondertussen probeert hij niet vast te raken in de valstrikken van een voorbarig medelijden, onbewust, met een milde afkeuring voor de zwakheid die zich voor hem onthult, met een ingekankerde scepsis, verveeld door het doorsnee-geval, entomologisch geïnteresseerd in de randverschijnselen, zeker van de regelmatige opeenvolging van ethisch sterke en zwakke figuren. De cliënt verdwijnt achter zijn zaak, ook de ambtenaar wordt door zijn arbeidsterrein opgeslokt. Intussen ratelt het geval in drie-, eventueel in viervoud in de schrijfmachine, rinkelt aan het eind van elke regel, net zolang tot het de beurt is van de geijkte slotformuleringen: ’Verder wenst hij niets naar voren te brengen, met zijn handtekening bekrachtigt hij het proces-verbaal. Datum als boven.’

Alsof ik vuistgrote brokken modder inslikte die ik verteren noch uitspuwen kon, zo kwam dit in het begin van mijn loopbaan op mij af. In de afgelopen tien jaar heb ik ongeveer dertigduizend keer gezegd: ’Gaat u zitten alstublieft.’ Mijn collega’s, de getuigen, de mensen die ergens aangifte van kwamen doen, nieuwsgierige journalisten en een paar goedaardige gekken niet meegerekend kwamen bijna alle bezoekers in een crisissituatie bij me. Hun moeilijkheden waren meestal overweldigend, straalden van hun hele lichaam af en waren onoplosbaar, zo voelde ik het tenminste in dit vertrek, en gingen even steevast gepaard met uitroepen als: ’Gelooft u me, het doet ontzettend pijn’, ’Ik houd het niet meer uit’, ’Ik ga kapot’, als het gierende geluid bij een bergkabelbaan hoort. En mijn manier van vragen doet veeleer denken aan een chirurgische ingreep waarbij de arts de zoëven geopende verse wonden weer dichtnaait zonder het gezwel aangeroerd te hebben.

Bij elke gelegenheid hoort een bepaalde gemoedsgesteldheid. In het circus lacht mijn cliënt, in het stoombad wordt hij rnelancholiek, in de tram vergeet hij zijn mond dicht te doen, bij bokswedstrijden komt hij in een agressieve, op begraafplaatsen in een pacifistische stemming. Naar deze kamer brengt hij enige monsters van het lijden mee dat hij ook aan zijn zoons en dochters heeft doorgegeven. Het is mogelijk dat de momentopname die ik van het hele mollengangenlabyrint van zijn op instorten staande jaren zie misleidend is. Gisteren heeft hij een schop gekregen, morgen vraagt men hem vergeving, overmorgen vleit men hem – en ik zie alleen maar het gisteren. Met enig voorbehoud verlaat ik me daar evenwel op. Al is het dan niet de man zelf, het zijn in ieder geval zijn omstandigheden die ik leer kennen. En de omtrekken van zijn misstappen – vergeleken met die van anderen – verraden mij wat uitsluitend voor zijn rekening komt, en daarbij vormt het onberekenbare deel slechts een bescheiden toegift op het berekenbare. Zijn omstandigheden zijn, zoals men dat pleegt te noemen, bekrompen. Als ambtenaar krijg ik inzage in zijn situatie, zijn gewoonten, zijn vroegere misstappen; al kom ik daarover niet alles aan de weet, toch is het wel zoveel dat ik zijn actieradius kan schatten. In werkelijkheid is dit alles echter niet hijzelf, maar slechts de cocon waarin hij rond kan spartelen. Spijtig identificeer ik mijn cliënt met al die omstandigheden, het gaat me aan het hart dat hij zich door al die dingen waarvan hij afhankelijk is maar zo weinig heeft kunnen waarmaken. Het zou al toe te juichen zijn als zijn relaties met zijn omgeving iets complexer zouden zijn, als hij zich aan wat variabeler leefgewoonten zou onderwerpen. Maar de graad van gecompliceerdheid van zijn systeem is ontmoedigend laag, zijn verdiensten karig, zijn woonomstandigheden gebrekkig, zijn inzicht vertroebeld, zijn lasten zwaar. Zijn bewegingsvrijheid is kleiner dan de gemiddelde, zijn emoties zijn ongeorganiseerd en geven aanleiding tot wrijvingen, soms zelfs tot botsingen. Dan vormt er zich een kring om hem heen, de autoriteiten verschijnen ten tonele om een vlotte doorstroming van het verkeer te verzekeren. Ik ben belast met de bescherming van zijn minderjarige kinderen en van de belangen van de staat, mijn plicht bestaat erin om tussen hem en zijn omstandigheden vrede te stichten en zijn bereidheid tot lijden officieel af te keuren. Ik doe datgene waartoe ik door de wet en mijn weifelend oordeel gemachtigd ben, en ik kijk verlamd toe hoe hij in een wrak wordt veranderd zodra de wet zich met hem gaat bemoeien.

Hans Hom

Publisher: Van Gennep, Amsterdam

Source of the quotation p. 17-20.

![]()

FLEURSDUMAL.NL MAGAZINE

More in: Konrad, György

.jpg)

Marcel Proust

(1871-1922)

Mozart

Italian at arms or Prince of Bavaria

His sad and icy eye enchanted by languor!

In his chilly gardens he encounters his heart

His bosom swells to shadow, where he nurses the light.

His tender German heart, – so deep a sigh!

Finally he tastes love’s idle being,

His hands too weak to hold his book

Beaming with hope in his charmed head.

Cherub, Don Juan! Standing in pressed flowers

Far from the lapse of memory

Such an amount of perfumes fan

Drying the tears the wind disperses

From Andalusian gardens to the tombs of Tuscany!

In the German park where troubles mist,

The Italian is still king of the night.

His breath makes the air soft and spiritual

And love drips from his enchanted flute

In the hot still shade of good-byes on a fine day

Of fresh sorbets, kisses and sky.

![]()

Marcel Proust poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Marcel Proust, Proust, Marcel

Ton van Reen

DE GEVANGENE VI

Het meisje

Het meisje was pas wakker. Nog maar net had ze haar ogen geopend. Ze dacht dat de dag een vuile dweil was die haar kamer kwam binnensluipen om vuil tegen de muren te blijven hangen. Die met de gordijnen alles vast leek te pakken in een wurggreep.

Ze kwam uit bed. Lag er iemand onder die haar bij de benen vastgreep en haar wilde naaien? Dat idee had ze altijd als ze opstond. Meestal keek ze onder het bed. Daar lag alleen een wal stof die je zo weg kon blazen, maar die toch ook op een berglandschap leek waar etter uit liep, als lava uit een vulkaan. Lekte de een of andere muur? Was het wel water dat uit de muur droop en aan het stof vrat?

Ze keek naar buiten, zag nog net dat meneer Pesche om de hoek van de straat verdween. Met zijn scharrelhandjes leek hij naar iemand te zwaaien. Meneer Pesche had een kop als een bloemkool en handjes als een mol. Straks zou hij ouwehoeren tegen de zwanen in de beek die tussen de tuinen van restaurant Varsgarten en hotel Eden door liep. Die zwanen waren ook dom genoeg. Ze waren zo vet als ganzen, vraten te veel en kwaakten erbij. Het was zonde dat het park van restaurant Varsgarten dicht lag te groeien. Het werd een oerwoud. Het park nam de kans natuurlijk waar. Wat was er leuker voor een park dan dicht te groeien?

Meneer Pesche was verantwoordelijk voor het wel en wee van het restaurant. Hij was de eigenaar en ging er eten, als enige en laatste klant. Zou de gerant het prettig vinden dat hij nog één klant had en dan nog wel de eigenaar? Tegen de asman praatte meneer Pesche wel eens. Dan had hij het over het vulgus uit de Libertystraat en het plebs uit de Tolsteeg. Waarschijnlijk zwaaide hij met zijn mollenhandjes naar de asman.

Die asman moest een tik van een mallemolen hebben gehad. Hij noemde zich asman. Of noemden alleen de mensen uit de Libertystraat hem zo? Het beroep van asman bestond helemaal niet. Wel dat van vuilnisophaler. Zo ver had de asman het nooit geschopt. Hij zat steeds dromerig voor zich uit te staren. Wanneer hij vuilnis zou moeten ophalen, zou hij alleen op de lege asvaten gaan zitten en de volle laten staan.

Vanuit het raam keek ze op zijn kaasachtige schedel. Ze had nooit anders geweten of de asman zat op het asvat voor het huis van de familie F. Net of hij het deksel bij weer en wind schoon wilde houden. Ze begreep niet waarom hij het deksel zo glimmend poetste. Niemand durfde het asvat nog te gebruiken en wie interesseerde het of een asvat wel of niet blonk? Nu zat de asman er weer vanaf vanmorgen vroeg. Was hij vannacht niet weg geweest van het asvat? Ze kon zich slecht voorstellen dat de asman enkel op het asvat zat om het deksel schoon te houden. Och, misschien was het zijn grootste geluk. Voor zijn grootste geluk mocht hij van haar best op het asvat blijven zitten.

De asman was het enige wezen dat leefde in de straat. Het viel daarom altijd op wanneer hij een voet verzette of zijn kont verschoof op het deksel van het asvat dat, wanneer hij er even niet op zat, blonk of de zon erop scheen.

(wordt vervolgd)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - De gevangene

Mireille Havet

(1898-1932)

Arlequin

Mon petit Arlequin

si triste sur le divan

dans la journée molle et que creuse l’orage

aux labours du printemps

tu as chu comme une feuille balancée

pétale détachée qui s’envole

En culotte de soie de toutes couleurs

tes jambes fines en lignes coupées

par les ramages

voyant paysage d’une féerie

de mauvais aloi

où les pommes ont des yeux

et les oiseaux trois pattes

Tu étales dans l’argenterie d’un crépuscule

tout balancé de pluie et d’arrosage

ta souplesse infernale

de sauts périlleux et de scandales

Arlequin mon petit camarade

aux gestes de pantin

qui donc aujourd’hui a tenu

la ficelle de ta belle âme

qui donc a tiré l’élastique de tes quatre membres

que je te vois si pâle et si défait

dans ce costume

qui appelle la bâtonnade

d’un pierrot ridicule

Les jardins ont versé leurs odeurs

sur la route

toute une procession de marronniers

en fleurs

de lilas doubles et de tulipes

quelqu’hirondelle basse écorcha ses ailes

au rosier

et l’orage s’est ouvert

ronronnant troupeau d’abeilles

au ciel électrique de lumière

Alors

abrités par ta maison claire

et mariés d’avance sous le joug diluvien

de l’averse

nous avons cherché

toi familier des planches

et des ramages et des fards

et moi voyageur prodigue au mouchoir

à carreaux faisant mon tour de France

la double douceur de nos chairs nerveuses

illuminées par la saison nouvelle

ses aubes claires et ses rossignols

j’entendais ruisseler les gouttières

et s’abreuver la terre molle

où germent les graines potagères

j’entendais rabattus par le vent

les volets claquer au balcon

et ces intermittences de tonnerre

Longtemps je garderai aux doigts

le souvenir de ta culotte soyeuse

je te cherchais à travers

l’arc-en-ciel

et l’odeur des géraniums

mon petit frère perdu dans les mascarades

et les confettis

mon petit dévoyé de l’école

que faisons-nous

Et pourquoi pas plutôt l’atlas ouvert

sur nos genoux

ou bien les rois de France

Apprendre enfin pour devenir des hommes

Ah ! tu es pris sous moi pris

nous nous entrouvrons sur le néant

du monde

Voilà que chancelle le masque de tes yeux

ta bouche trop rouge

où j’ai mordu l’admirable forme

sa lampe à la main

Arlequin est à la fenêtre

son profil ausculte la nuit

la douteuse lumière pose

des ronds ensoleillés

Sur ses hanches satinées

de danseur immobile

et je me tourne inquiet

pour mieux voir

Car dans mon rêve

j’avais ôté son masque

son petit masque de velours

Si bien ajusté

Cependant

à ses joues chaudes

et son visage entier

m’était apparu

Arlequin

regarde-moi

du mensonge

dans un arc si pur

Vais-je découvrir enfin le haut de ton visage

car tes pupilles claires

dans l’échancrure noire

Arlequin

vais-je savoir

quel dieu

tu es

Mais

dans la nuit venue

où se dresse sur un nuage tourmenté

la petite serpe de la lune enchantée

qui servit à trancher

tant de pavots magiques

Dans la nuit où se recomposent

les jardins échevelés par la pluie

et leurs odeurs mêlées

jeu de patience que brouilla l’orage

je m’éveille

Aladin

Surpris par un rêve incroyable

Est-il vrai que c’était mon visage

une telle ressemblance est-elle possible

mon visage sous ton masque

que j’embrassai toute une nuit

Bientôt, dit-il, je te quitterai pour toujours

le jeu a duré bien longtemps pour mon arlequinade

je ne sais vraiment ce qu’il m’a pris

entend les coqs qui ouvrent les routes

de l’aurore

II faut que j’aille réjouir les villes

leur petit guignol de planches et d’or

avant que le matin ne ternisse de rosée

mon brillant costume

Il faut que j’aille danser

rejoindre Colombine

et tous les autres

que serait la comédie sans Arlequin

Vraiment que serait la comédie

tu n’y songes pas

Il parlait à demi tourné vers la fenêtre

et l’ombre me cachait sa figure

c’est alors que m’étant levé

pour le rejoindre

d’une jambe souple

il sauta

dans le vide

Arlequin

le masque détaché par la chute

vient s’abattre oiseau triste

dans mes mains

et je ne vis plus

sur les routes de l’aurore

S’en allant à reculons

avec des gestes de parade foraine

qu’un petit pantin mécanique et bouffon

dont le visage levé

IDENTIQUE AU MIEN

…..souriait obstinément vers le jour

Revue Les Écrits Nouveaux Tome IX – nr 6 (juin 1922)

Mireille Havet poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive G-H, Havet, Mireille, Mireille Havet

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature