Fleurs du Mal Magazine

A fascinating glimpse into design behind the Iron Curtain, revealed through the products and graphics of everyday Soviet life

This captivating survey of Soviet design from 1950 to 1989 features more than 350 items from the Moscow Design Museum’s unique collection.

This captivating survey of Soviet design from 1950 to 1989 features more than 350 items from the Moscow Design Museum’s unique collection.

From children’s toys, homewares, and fashion to posters, electronics, and space-race ephemera, each object reveals something of life in a planned economy during a fascinating time in Russia’s history.

Organized into three chapters – Citizen, State, and World – the book is a micro-to-macro tour of the functional, kitsch, politicized, and often avant-garde designs from this largely undocumented period.

Designed in the USSR: 1950-1989

Moscow Design Museum

Publisher: Phaidon Press

April 2018

Editions: Hardback

Language: English

Price: €34.95

Format: Hardback

Size: 270 x 205 mm

Pages: 240 pp

Illustrations: 350 illustrations

ISBN-10: 0714875570

ISBN-13: 978-0714875576

new books

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Bookstores, Art & Literature News, Design, Illustrators, Illustration, Photography

Grief

Exultant whirlwind wrung the branches ;

And the weak leaves were loosed with power.

I heard the pelting dissonances ;

Anguish in the autumn shower.

But living petals now take wing

Like butterflies with dusky flashes;

April flutters her white ashes

Inaudibly, remembering.

Gladys Cromwell

(1885-1919)

Grief

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive C-D, Cromwell, Gladys, Gladys Cromwell

Poe’s cottage at Fordham

Here lived the soul enchanted

By melody of song;

Here dwelt the spirit haunted

By a demoniac throng;

Here sang the lips elated;

Here grief and death were sated;

Here loved and here unmated

Was he, so frail, so strong.

Here wintry winds and cheerless

The dying firelight blew,

While he whose song was peerless

Dreamed the drear midnight through,

And from dull embers chilling

Crept shadows darkly filling

The silent place, and thrilling

His fancy as they grew.

Here with brows bared to heaven,

In starry night he stood,

With the lost star of seven

Feeling sad brotherhood.

Here in the sobbing showers

Of dark autumnal hours

He heard suspected powers

Shriek through the stormy wood.

From visions of Apollo

And of Astarte’s bliss,

He gazed into the hollow

And hopeless vale of Dis,

And though earth were surrounded

By heaven, it still was mounded

With graves. His soul had sounded

The dolorous abyss.

Poor, mad, but not defiant,

He touched at heaven and hell.

Fate found a rare soul pliant

And wrung her changes well.

Alternately his lyre,

Stranded with strings of fire,

Led earth’s most happy choir,

Or flashed with Israfel.

No singer of old story

Luting accustomed lays,

No harper for new glory,

No mendicant for praise,

He struck high chords and splendid,

Wherein were finely blended

Tones that unfinished ended

With his unfinished days.

Here through this lonely portal,

Made sacred by his name,

Unheralded immortal

The mortal went and came.

And fate that then denied him,

And envy that decried him,

And malice that belied him,

Here cenotaphed his fame.

John Henry Boner

(1845-1903)

poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Edgar Allan Poe, Poe, Edgar Allan

Ellen Hinsey’s new book-length sequence, The Illegal Age, is a powerful investigation into the twentieth-century’s dark legacy of totalitarianism and the rise of political illegality.

It explores the enduring potential for human beings to set neighbour against neighbour and commit final acts of violence. A book of lyrical reflection and prophesy, The Illegal Age chronicles the arrival of a new, disquieting reality unfolding in our midst.

It explores the enduring potential for human beings to set neighbour against neighbour and commit final acts of violence. A book of lyrical reflection and prophesy, The Illegal Age chronicles the arrival of a new, disquieting reality unfolding in our midst.

As Marilyn Hacker has written, “In dialogue with Celan, Szymborska, Milosz… this is a daring text – for its political acuity, and for its demonstration of the power in poetry to recount, remember, move the heart while opening the mind.”

Written in parallel with her first-hand research into the rise of authoritarianism carried out over the last decade, Hinsey’s volume warns that – rather than an “Age of Anxiety” – we may indeed be facing the start of the “Illegal Age”.

Ellen Hinsey was born in 1960 in Boston, Massachusetts. For the last two decades she has lived in Europe. She received a Bachelor of Fine Arts degree from Tufts University and a graduate degree from Université de Paris VII. She has taught at the French graduate school the Ecole Polytechnique and currently teaches at Skidmore College s Paris program. She is the international correspondent for The New England Review.

Hinsey’s work is concerned with history, ethics and democracy. Her first-hand accounts and analyses of the impact of the 2012 Russian presidential elections, the 2010 Polish presidential plane crash, Hungarian politics, Václav Havel’s ethical legacy and post-1989 German reconstruction have been published in The New England Review. A selection of these essays are included in her book <ik>Mastering the Past: Contemporary Central and Eastern Europe and the Rise of Illiberalism (Telos Press, 2017). Her current work addresses global authoritarianism.

Hinsey’s first book, Cities of Memory, draws on her experiences at the Berlin Wall on the weekend of November 9, 1989, as well as in Prague during the Velvet Revolution. The book received the Yale Series Award and was published by Yale University Press in 1996. Her second book, The White Fire of Time (Wesleyan University Press, 2002 / Bloodaxe Books, 2003), written after a family tragedy, is an exploration of ethics and renewal.

Later, you will realize that compromise is the wood that burns

Most brightly in the hour before regret.

But by then, all the doors will have been marked in yellow chalk.

Still, let us not pass each other this final time, without recognition,

Without looking each other in the eye.

Remember: in the ink-light of testimony, a record may still be kept.

Ellen Hinsey (fragment)

The Illegal Age

by Ellen Hinsey (Author)

PBS Autumn Choice 2018

Publisher: Arc Publicationas

July 2018

120 pages

Language: English

ISBN-10: 191146938X

ISBN-13: 978-1911469384

Product Dimensions: 15 x 2.2 x 21 cm

Hardcover £13.99

Paperback £10.99

new books

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, Archive G-H, Art & Literature News, EDITOR'S CHOICE

Hij loopt naar de vlonder en springt in zijn bootje. Hij moet hard roeien, tegen de stroom in. Hij hoort zijn moeder zingen. Ze is aan het werk op haar veldje bij de Wijer. Ze plukt frambozen. Ze zwaait naar hem.

`Kom je me helpen, druifje?’

`Val dood met die lieve woordjes’, wil hij roepen, maar hij doet het niet.

Ze zingt liedjes, half voor hem, half voor zichzelf. Ze zingt altijd als ze op het veldje bezig is.

Hij legt de boot vast en gaat haar helpen.

Uit de korf met rode vruchten stijgt een zoete lucht op. Mels steekt alle frambozen die hij plukt in zijn mond. Met het puntje van zijn tong haalt hij er de pitjes uit.

Uit de korf met rode vruchten stijgt een zoete lucht op. Mels steekt alle frambozen die hij plukt in zijn mond. Met het puntje van zijn tong haalt hij er de pitjes uit.

`Je bent een gulzigaard’, zingt moeder. `Je mond is rood tot aan je oren. Van je kin druppelt bloed.’

`Frambozen zitten het liefst in mijn buik’, zegt Mels.

`Ze zijn rijp omdat ze van je houden’, zingt moeder. `Ze geuren omdat ze dan zeker weten dat jij ze plukt.’

`Moeder, weet jij waarom Chinezen scheve ogen hebben?’

`Omdat ze achterstevoren zijn geboren’, lacht moeder.

`Waarom hebben ze doorzichtige oorschelpen?’

`Omdat ze van porselein zijn gemaakt.’

`Waarom hebben ze zwart haar?’

`Omdat het witte haar op was toen God de Chinezen schiep.’

`Ze trappen hemelbeestjes dood.’

`Doen ze dat?’

`Waarom eten ze honden?’

`Dat doen ze niet!’

`Dat doen ze wel. Ik zag het op een foto in een boek.’

`Goh, dat wist ik niet.’

`Ze hangen mensen op aan hun kin. Je mag mijn boek wel zien.’

`Waarom wil je dan naar China?’

`Ik wil weten waar Thija vandaan komt. Ze houdt van mij.’

`Hoe weet je dat?’

`Ze weet alles van mij. Ze weet altijd waar ik ben, ook als ze me niet ziet.’

`Dan is ze helderziend. Dat lijkt me typisch iets voor Chinezen. Doordat ze alles van tevoren weten, zetten ze de wereld op zijn kop.’ Ze zingt een liedje over Chinezen. Liedjes verzint ze altijd zelf.

Hij loopt naar de Wijer en gaat langs het water liggen, zijn hoofd dicht bij de oppervlakte, turend naar vissen.

`Pas op voor de duivel in de beek’, roept zijn moeder. `Houd je ogen niet open onder water, want dan pakt de duivel je bij je haren.’

Toch houdt hij zijn hoofd onder water om met wijdopen ogen naar de slakken en de modderkruipers op de bodem te kijken. Zijn moeder heeft gelijk. Hij kijkt recht in de ogen van de duivel die van onder de bladeren van een lisdodde naar hem ligt te loeren. Vlug haalt hij zijn hoofd boven water, houdt het schuin naar links en dan naar rechts om het water uit zijn oren te laten lopen en ziet aan de overkant Thija aankomen op de hoge zwarte fiets van haar moeder. Zo dun en zo klein is ze, tussen de stangen van de fiets, niet meer dan een trekpop waarvan de benen mechanisch bewegen, aangedreven door de grote strik die stijf gesteven op haar hoofd staat.

`Er zit kroos in je haar’, zegt Thija als ze afstapt en de fiets in het gras laat vallen.

`Ik heb de duivel in het water gezien.’

`Een snoek?’

`Het was echt de duivel.’

`Ik wist dat je hier was’, zegt Thija. `Ik hoorde je moeder zingen.’

Mels kuiert naar het bruggetje, tien meter verderop. Het is niet meer dan een brede plank, die wit is van de schimmel. Hij loopt naar de overkant.

`Het is mooi, dat wier in je haar’, lacht Thija.

`Jouw strik is ook mooi. Je moeder is knap.’

`Dat kan ik zelf.’

`Dat kun je niet.’

Ze houdt haar armen omhoog, alsof ze wil bewijzen dat ze de strik zelf kan strikken, zodat haar stijve jurk wijduit gaat staan en de bloemetjesrand van haar roze onderjurk laat zien.

`Ik ben groter dan jij’, zegt Mels, op zijn tenen staand.

`Je bent groter dan mijn buik voordat je werd geboren’, zingt zijn moeder terwijl ze met de mand frambozen over de plank loopt. `Ik zal nog van je houden, ook al word je net zo groot als de kerktoren, ook al word je net zo dik als de silo.’ Dikke druppels donkerrood sap druipen uit de mand op het schimmelende bruggetje. Ze blijven er als bloedspatten op liggen. Sap druppelt in de Wijer en trekt roze strepen in het water die oplossen in het kristalheldere riviertje.

Moeder loopt langs de kinderen die in het gras zijn gaan zitten, met hun benen in het water.

`Als jullie uitverteld zijn, dan kom je maar naar huis’, zingt zijn moeder. `Dan krijg je karnemelk met frambozensap. En duizend gouden oren om het lied van duizend krekels te horen.’

`Krekels zingen niet’, zegt Thija.

`Je leert nog wel naar hun zang te luisteren. Mag ik je fiets lenen? Dan ben ik thuis voordat mijn korf is leeggedruppeld.’ Moeder zet het mandje op de bagagedrager, stapt op de fiets en rijdt zingend over het pad naar huis. Een rood druipspoor blijft achter in het zand.

`Jouw moeder is een beetje gek’, zegt Thija.

`Net als die van jou dus.’

`Precies, zo bedoel ik het.’

Tijger komt aanfietsen, zijn hoofd rood van de inspanning. Hij ploft naast hen neer.

`Waar was je?’

`Ik had de keuken moeten witten, maar ik heb op bed liggen lezen. Mijn moeder heeft een tijdschrift gekregen van missionarissen die in China werken. Als je wilt mag je het lezen. Het is niet zo wreed als dat boek.’

`In China zijn alle wegen rood’, zegt Thija.

`Van het bloed, natuurlijk.’

`Het zand is rood. De bomen zijn blauw. Het water is groen. In China is alles anders.’

`Je praat alsof je het met eigen ogen hebt gezien’, zegt Tijger.

`Dat is ook zo. De laatste keer logeerde ik bij mijn grootmoeder in Sjanghai. Ze heeft een hoedenwinkel.’

`Van die grote hoeden die op woks lijken?’ vraagt Mels.

`Precies. Maar ook zijden hoeden. En hoeden van glas.’

`Dat bestaat niet.’

`Dun glas, zo dun als papier. Als je een hoed van glas opzet, knispert je haar. Veel mensen komen hoeden bij haar passen. Ze kent de modellen van alle hoeden uit heel China omdat ze vroeger een vis is geweest. Ze heeft door alle rivieren van China gezwommen. Vanuit het water heeft ze naar de mensen gekeken. Als ze haar hoeden zit te naaien, vertelt ze me over wat ze in het water heeft meegemaakt. Ze spreekt de taal van de vissen. Mij heeft ze die taal ook geleerd, een beetje.’

`Kun je ook met de vissen in de Wijer praten?’

`Die spreken geen Chinees.’

Ze trekt haar benen uit het water en pakt haar schoenen.

`Ik hoor een klok’, zegt Tijger opeens.

Ze luisteren.

`Ik hoor niks’, zegt Mels.

`Ik hoor hem weer.’

Ze luisteren, hun oor aan het water. Nu horen de anderen het ook.

`Het verdronken kasteel’, zegt Tijger.

`Hoor je de mensen in het kasteel ook?’ vraagt Thija.

`Ik hoor paarden.’

`Ridders?’

`En een prinses. Ze zingt en ze speelt op een harp.’

Opeens ziet Mels op het bruggetje de dikke pad met uitpuilende ogen en opgeblazen wangen. Als hij brult maakt hij het geluid van een klok. Maar Mels doet net of hij van niets weet en blijft zijn oor aan het water houden, net als de anderen.

`Nu hoor ik de prinses ook’, zegt hij. `Ze roept. Ze zit opgesloten in een toren. Ze wil bevrijd worden.’

`Waarom is ze opgesloten?’ vraagt Thija.

`Ze wil niet trouwen met de ridder aan wie haar vader haar heeft geschonken. Ze wil een andere man.’

`Ze maken haar dood’, zegt Tijger. `Ik hoor niets meer. Ook de klok niet.’

Mels ziet de dikke vroedmeesterpad verdwijnen in het gras.

`Kijk!’ Tijger wijst op een dun rood spoor in het water, dat blinkt als olie. `Bloed. Ze hebben haar de keel doorgesneden.’

Mels houdt een vinger in het rode spul. Er blijft een beetje roest op zijn huid achter. Het lijkt op gestold bloed.

`Zo’n straf heeft ze niet verdiend’, zegt Thija. `We hadden haar moeten bevrijden.’

`Dat zouden de anderen in het kasteel niet hebben begrepen’, zegt Tijger. `Toen het kasteel verzonk, eeuwen geleden, hadden vrouwen niets te vertellen.’

`Stomme kerels.’

`Andere tijden, andere zeden.’

`Denk jij er soms ook zo over?’ vraagt Thija.

`Ik zeg alleen wat ze tóén dachten.’ Tijger voelt zich aangevallen. `Jij mag trouwen met wie je wilt hoor. Met Mels, of met mij.’

`En als ik jullie allebei niet wil?’

`Vertel geen onzin. Wie zou je anders willen dan een van ons twee?’

Verbijsterd hoort Mels de discussie aan. Het is alsof ze plots onder glazen stolpen zitten. Ieder alleen. Alles is breekbaar.

`En als ik niet trouw?’

`Heb ik nooit over nagedacht’, zegt Tijger. `Ik wil hierover helemaal niet praten.’

`Jij begint er toch zelf over!’

`Nee, jij. Jij zei dat ik net zo over vrouwen dacht als die ridders.’

`Je vertelde dat verhaal van die opgesloten jonkvrouw alleen maar om me uit te dagen. Je wilt weten voor wie ik kies.’

Het hoge woord is eruit. Thija schrikt er zelf van.

Ze begint te huilen, springt op en loopt weg. De jongens kijken haar na, tot ze verdwijnt tussen de huizen.

Mels trekt zijn schoenen aan.

`We hebben een groot probleem.’ Tijger plukt de harige bolletjes van de distels uit zijn sokken.

`Het probleem is dat we vrienden zijn’, zegt Mels. `We moeten het haar gewoon vragen.’

`Nee’, schrikt Tijger. `Stel je voor dat ze voor jou kiest. Dan weet ik liever niets.’ Hij rijdt naar huis.

Mels springt in de boot en roeit stroomopwaarts. Hij wil alleen zijn.

Ton van Reen: Het diepste blauw (065)

wordt vervolgd

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book Stories, - Het diepste blauw, Archive Q-R, Reen, Ton van

In the period between 1815 and 1820, Mary Shelley wrote her most famous novel, Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus, as well as its companion piece, Mathilda, a tragic incest narrative that was confiscated by her father, William Godwin, and left unpublished until 1959. She also gave birth to four—and lost three—children.

In this hybrid text, Rachel Feder interprets Frankenstein and Mathilda within a series of provocative frameworks including Shelley’s experiences of motherhood and maternal loss, twentieth-century feminists’ interests in and attachments to Mary Shelley, and the critic’s own experiences of pregnancy, childbirth, and motherhood.

In this hybrid text, Rachel Feder interprets Frankenstein and Mathilda within a series of provocative frameworks including Shelley’s experiences of motherhood and maternal loss, twentieth-century feminists’ interests in and attachments to Mary Shelley, and the critic’s own experiences of pregnancy, childbirth, and motherhood.

Harvester of Hearts explores how Mary Shelley’s exchanges with her children—in utero, in birth, in life, and in death—infuse her literary creations. Drawing on the archives of feminist scholarship, Feder theorizes “elective affinities,” a term she borrows from Goethe to interrogate how the personal attachments of literary critics shape our sense of literary history.

Feder blurs the distinctions between intellectual, bodily, literary, and personal history, reanimating the classical feminist discourse on Frankenstein by stepping into the frame.

Feder blurs the distinctions between intellectual, bodily, literary, and personal history, reanimating the classical feminist discourse on Frankenstein by stepping into the frame.

The result—at once an experimental book of literary criticism, a performative foray into feminist praxis, and a deeply personal lyric essay—not only locates Mary Shelley’s monsters within the folds of maternal identity but also illuminates the connections between the literary and the quotidian.

Rachel Feder is an assistant professor of English and literary arts at the University of Denver. Her scholarly and creative work has appeared in a range of publications including ELH, Studies in Romanticism, and a poetry chapbook from dancing girl press.

Rachel Feder (Author)

Harvester of Hearts

Motherhood under the Sign of Frankenstein

Cloth Text – $99.95

ISBN 978-0-8101-3753-0

Paper Text – $34.95

ISBN 978-0-8101-3752-3

August 2018

Women’s Studies

Literary Criticism

152 pages

Northwestern University Press

new books

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Book Stories, Archive E-F, Archive S-T, Art & Literature News, Mary Shelley, Shelley, Mary, Shelley, Percy Byssche, Tales of Mystery & Imagination

Requiescat

Strew on her roses, roses,

And never a spray of yew.

In quiet she reposes:

Ah! would that I did too.

Her mirth the world required:

She bathed it in smiles of glee.

But her heart was tired, tired,

And now they let her be.

Her life was turning, turning,

In mazes of heat and sound.

But for peace her soul was yearning,

And now peace laps her round.

Her cabin’d, ample Spirit,

It flutter’d and fail’d for breath.

To-night it doth inherit

The vasty hall of Death.

Matthew Arnold

(1822-1888)

poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: #More Poetry Archives, Archive A-B, Archive A-B, Galerie des Morts

Programma 2018 Lustwarande

Programma 2018 Lustwarande

26 mei – 23 september

In 2018 presenteert Lustwarande het volgende programma:

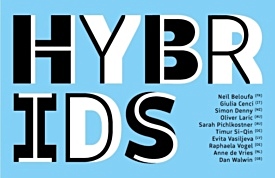

Hybrids, een expositie over de zogeheten post-internet generatie, die een artistiek vocabulaire ontwikkelt dat zeer hybride van aard is, en Brief Encounters ‘18, momenten van event sculpture die op twee middagen plaatsvinden, in mei en in september.

Voor 2018 staat ook de publicatie Sculpture in the Anthropocene gepland, die de exposities Luster (2016), Disruption (2017) en Hybrids bundelt en contextualiseert.

Voor 2018 staat ook de publicatie Sculpture in the Anthropocene gepland, die de exposities Luster (2016), Disruption (2017) en Hybrids bundelt en contextualiseert.

Hybrids focust op een generatie jonge kunstenaars, vaak aangeduid als post-internet, die de allesomvattende, digitale en beeldverzadigde wereld als uitgangspunt voor hun werk nemen. Dit resulteert in een beeldtaal die zeer hybride is.

H y b r i d s

23 juni – 23 september 2018

tien post-internet kunstenaars

Neïl Beloufa (FR)

Giulia Cenci (IT)

Simon Denny (NZ)

Oliver Laric (AU)

Sarah Pichlkostner (AU)

Timur Si-Qin (DE)

Evita Vasiljeva (LV)

Raphaela Vogel (DE)

Anne de Vries (NL)

Dan Walwin (GB)

Curatoren: Chris Driessen en David Jablonowski

B r i e f E n c o u n t e r s

26 mei & 16 september 2018

Onder de titel Brief Encounters vinden er jaarlijks een aantal event sculptures plaats, vormen van sculptuur die in tijd begrensd zijn. De duur van een werk kan variëren van een paar minuten tot enkele maanden. Deze focus op event sculpture vloeit voort uit de toenemende aandacht voor in tijd begrensde kunst.

# Meer info op website fundament foundations

Lustwarande 2018

park De Oude Warande

Bredaseweg 441 – Tilburg

expo

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Art & Literature News, Dutch Landscapes, Exhibition Archive, Fundament - Lustwarande, Land Art

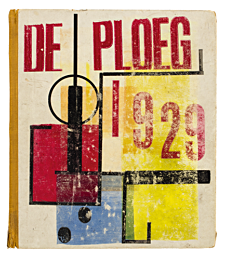

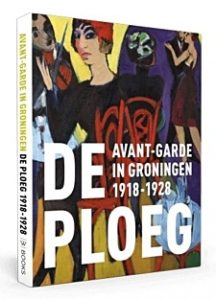

In deze grote overzichtstentoonstelling maken we kennis met het spannende culturele klimaat in Groningen aan het begin van de 20ste eeuw: de periode waarbinnen De Ploeg is ontstaan.

Het museum laat ruim honderd werken zien, waaronder schilderijen, tekeningen, drukwerk en grafiek van Ploegleden zoals Jan Wiegers, Johan Dijkstra en Jan Altink. In contrast met werk van coryfeeën zoals Jozef Israëls, H.W. Mesdag, Otto Eerelman en tijdgenoten. Het toont hoe de ‘jonge wilden’ zich losmaakten van de toenmalige gevestigde orde. Daarnaast is er aandacht voor het werk van Ernst Ludwig Kirchner en Vincent van Gogh, die beiden van groot belang zijn geweest voor de schilderkunstige ontwikkeling binnen De Ploeg.

Het museum laat ruim honderd werken zien, waaronder schilderijen, tekeningen, drukwerk en grafiek van Ploegleden zoals Jan Wiegers, Johan Dijkstra en Jan Altink. In contrast met werk van coryfeeën zoals Jozef Israëls, H.W. Mesdag, Otto Eerelman en tijdgenoten. Het toont hoe de ‘jonge wilden’ zich losmaakten van de toenmalige gevestigde orde. Daarnaast is er aandacht voor het werk van Ernst Ludwig Kirchner en Vincent van Gogh, die beiden van groot belang zijn geweest voor de schilderkunstige ontwikkeling binnen De Ploeg.

Avant-garde in Groningen. De Ploeg 1918-1928

100 jaar De Ploeg

Nog t/m 04 november 2018

Groninger museum, Museumeiland 1, 9711 ME Groningen

http://www.groningermuseum.nl

Het ontstaan van De Ploeg in 1918

Het ontstaan van De Ploeg in 1918

Kunstkring De Ploeg ontstond in juni 1918 als reactie op de “Tentoonstelling van werk van Groningsche Kunstenaars” in het Kunstlievend Genootschap Pictura. Hierbij was een groot aantal jonge kunstenaars niet uitgenodigd. Voor schilders zoals Jan Wiegers, Jan Altink en Johan Dijkstra was het duidelijk dat de negentiende-eeuwse schilderkunstige idealen afgeschud moesten worden. Zij zochten aansluiting bij meer contemporaine ontwikkelingen in de beeldende kunst. Het toeval zou hen daarbij een handje helpen. Jan Wiegers die gedurende een gezondheidskuur in Davos (1920-1921) in Zwitserland bevriend was geraakt met Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, introduceerde in Groningen een schilderkunst, die verwant is aan het Duitse expressionisme.

Publicatie bij de tentoonstelling

Publicatie bij de tentoonstelling

Bij de tentoonstelling is het boek Avant- garde in Groningen. De Ploeg 1918-1928 verschenen, waarin niet alleen het ontstaan maar ook de voorgeschiedenis van De Ploeg aan bod komt.

De publicatie komt tot stand vanuit een samenwerking van het Groninger Museum met de Stichting 100 jaar De Ploeg en WBOOKS. Het boek verscheen tijdens de Boekenweek in maart 2018.

Avant-garde in Groningen- De Ploeg 1918-1928

Auteurs: Anneke de Vries, Doeke Sijens, Egge Knol, Han Steenbruggen, Henk van Os, Jikke van der Spek, Kees van der Ploeg, Mariëtta Jansen, Mieke van der Wal, Peter Vroege

€ 29,95

ISBN 9789462582484

Aantal pagina’s 272

Illustraties ca 350 afbeeldingen

Formaat 24,5 x 31 cm

Uitvoering Gebonden

Taal Nederlands

2018

Uitg. W-Books

In samenwerking met Groninger Museum & Stichting 100 jaar De Ploeg

new books

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Book Stories, Archive U-V, Art & Literature News, De Ploeg, Hendrik Nicolaas Werkman, Werkman, Hendrik Nicolaas

Lyrics and never-before-seen poetry and sketches from the iconic musician of Florence and the Machine

Songs can be incredibly prophetic, like subconscious warnings or messages to myself, but I often don’t know what I’m trying to say till years later.

Songs can be incredibly prophetic, like subconscious warnings or messages to myself, but I often don’t know what I’m trying to say till years later.

Or a prediction comes true and I couldn’t do anything to stop it, so it seems like a kind of useless magic.

Since forming Florence + The Machine in 2007, Florence Welch has written three albums, Lungs, Ceremonials, and How Big How Blue How Beautiful, all of which have been chart toppers all over the world, and she has been nominated and has won numerous international awards.

Useless Magic

Lyrics and Poetry

By Florence Welch

Hardcover

Publ. Jul 10, 2018

288 Pages

$35.00

Published by Crown Archetype

ISBN 9780525577157

new books

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: #Editors Choice Archiv, Archive W-X, Art & Literature News, Florence Welch

Presentiment

“Sister, you’ve sat there all the day,

Come to the hearth awhile;

The wind so wildly sweeps away,

The clouds so darkly pile.

That open book has lain, unread,

For hours upon your knee;

You’ve never smiled nor turned your head;

What can you, sister, see?”

“Come hither, Jane, look down the field;

How dense a mist creeps on!

The path, the hedge, are both concealed,

Ev’n the white gate is gone

No landscape through the fog I trace,

No hill with pastures green;

All featureless is Nature’s face.

All masked in clouds her mien.

“Scarce is the rustle of a leaf

Heard in our garden now;

The year grows old, its days wax brief,

The tresses leave its brow.

The rain drives fast before the wind,

The sky is blank and grey;

O Jane, what sadness fills the mind

On such a dreary day!”

“You think too much, my sister dear;

You sit too long alone;

What though November days be drear?

Full soon will they be gone.

I’ve swept the hearth, and placed your chair,.

Come, Emma, sit by me;

Our own fireside is never drear,

Though late and wintry wane the year,

Though rough the night may be.”

“The peaceful glow of our fireside

Imparts no peace to me:

My thoughts would rather wander wide

Than rest, dear Jane, with thee.

I’m on a distant journey bound,

And if, about my heart,

Too closely kindred ties were bound,

‘Twould break when forced to part.

“‘Soon will November days be o’er:’

Well have you spoken, Jane:

My own forebodings tell me more–

For me, I know by presage sure,

They’ll ne’er return again.

Ere long, nor sun nor storm to me

Will bring or joy or gloom;

They reach not that Eternity

Which soon will be my home.”

Eight months are gone, the summer sun

Sets in a glorious sky;

A quiet field, all green and lone,

Receives its rosy dye.

Jane sits upon a shaded stile,

Alone she sits there now;

Her head rests on her hand the while,

And thought o’ercasts her brow.

She’s thinking of one winter’s day,

A few short months ago,

Then Emma’s bier was borne away

O’er wastes of frozen snow.

She’s thinking how that drifted snow

Dissolved in spring’s first gleam,

And how her sister’s memory now

Fades, even as fades a dream.

The snow will whiten earth again,

But Emma comes no more;

She left, ‘mid winter’s sleet and rain,

This world for Heaven’s far shore.

On Beulah’s hills she wanders now,

On Eden’s tranquil plain;

To her shall Jane hereafter go,

She ne’er shall come to Jane!

Charlotte Brontë

(1816-1855)

poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Archive A-B, Brontë, Anne, Emily & Charlotte

My Last Duchess

That’s my last Duchess painted on the wall,

Looking as if she were alive. I call

That piece a wonder, now : Frà Pandolf’s hands

Worked busily a day, and there she stands.

Will’t please you sit and look at her ? I said

‘Frà Pandolf’ by design, for never read

Strangers like you that pictured countenance,

The depth and passion of its earnest glance,

But to myself they turned (since none puts by

The curtain I have drawn for you, but I)

And seemed as they would ask me, if they durst,

How such a glance came there ; so, not the first

Are you to turn and ask thus. Sir, ’t was not

Her husband’s presence only, called that spot

Of joy into the Duchess’ cheek : perhaps

Frà Pandolf chanced to say ‘Her mantle laps

Over my lady’s wrist too much,’ or ‘Paint

Must never hope to reproduce the faint

Half-flush that dies along her throat :’ such stuff

Was courtesy, she thought, and cause enough

For calling up that spot of joy. She had

A heart―how shall I say ?―too soon made glad,

Too easily impressed ; she liked whate’er

She looked on, and her looks went everywhere.

Sir, ’t was all one! My favour at her breast,

The dropping of the daylight in the West,

The bough of cherries some officious fool

Broke in the orchard for her, the white mule

She rode with round the terrace―all and each

Would draw from her alike the approving speech,

Or blush, at least. She thanked men,―good! but thanked

Somehow―I know not how―as if she ranked

My gift of a nine-hundred-years-old name

With anybody’s gift. Who’d stoop to blame

This sort of trifling? Even had you skill

In speech―(which I have not)―to make your will

Quite clear to such an one, and say, ‘Just this

Or that in you disgusts me ; here you miss,

Or there exceed the mark’―and if she let

Herself be lessoned so, nor plainly set

Her wits to yours, forsooth, and made excuse,

―E’en then would be some stooping ; and I choose

Never to stoop. Of sir, she smiled, no doubt,

Whene’er I passed her ; but who passed without

Much the same smile? This grew ; I gave commands ;

Then all smiles stopped together. There she stands

As if alive. Will’t please you rise ? We’ll meet

The company below, then. I repeat,

The Count your master’s known munificence

Is ample warrant that no just pretence

Of mine for dowry will be disallowed ;

Though his fair daughter’s self, as I avowed

At starting, is my object. Nay, we’ll go

Together down, sir. Notice Neptune, though,

Taming a sea-horse, thought a rarity,

Which Claus of Innsbruck cast in bronze for me!

Robert Browning (1812 – 1889)

My Last Duchess

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Browning, Robert

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature