Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Hiroo Onoda zit 29

jaar zonder nieuws

Thuis groeide een compleet nieuw

geslacht op terwijl hij door gebladerte

spiedde, voortdurend op zijn hoede:

maar niemand duurde almaar langer.

Pal in zijn oerwoud, van alles afgesneden.

Het zwaard nooit wijkend van de zij,

geweren tot vervelens toe gesmeerd.

Hij had geleerd hoe stand te houden.

Dagelijks menu banaan, gedroogd soms,

en vogels uit de lucht. De slapen licht

en bol van zege. Meer dan tienduizend

dagen en nachten de vijand in het hoofd.

Zelfs een havik is tussen kraaien een arend,

o zoon van de bloedrode zon.

Bert Bevers

Uit: Onaangepaste tijden, Zinderend, Bergen op Zoom, 2006

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Bevers, Bert

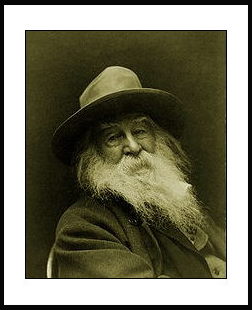

Walt Whitman

(1819 – 1892)

Poets to come!

1

Poets to come!

Not to-day is to justify me, and Democracy, and what we are for;

But you, a new brood, native, athletic, continental, greater than before

known,

You must justify me.

2

I but write one or two indicative words for the future,

I but advance a moment, only to wheel and hurry back in the darkness.

I am a man who, sauntering along, without fully stopping, turns a casual

look upon you, and then averts his face,

Leaving it to you to prove and define it,

Expecting the main things from you.

Walt Whitman poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive W-X, Whitman, Walt

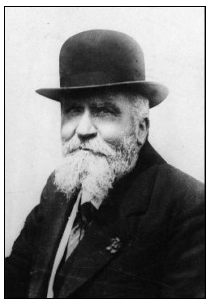

Jean Jaurès

(1859 – 1914)

La Couleur Fille De La Lumière

Pourquoi la couleur ne serait-elle pas un produit de notre sphère? Pourquoi ne supposerait-elle pas des conditions qui ne soient pas réalisées dans l’indifférence de l’espace infini? Elle ne se manifeste aux sens qu’à la rencontre de la lumière et de ce qui est essentiellement contraire à la lumière, les corps résistants. Pourquoi donc supposer qu’elle est déjà contenue dans la lumière? On a la ressource de dire qu’elle s’y cache et qu’elle attend, pour se montrer, que la libre expansion de la clarté rencontre un obstacle. Mais il est permis de penser aussi que ce qui se cache si bien n’existe pas encore ; la couleur est fille de la lumière et de notre monde corporel et lourd. Pourquoi en appesantir la lumière elle-même dans son expansion une et simple à travers l’infini? Quel sens auraient le vert et le rouge dans les espaces indifférents? Ici ils résultent de la vie et ils l’expriment dans son rapport avec la lumière; hors de la sphère vivante, ils n’ont pas de sens . . .

Par les couleurs, la lumière fait amitié avec notre monde: la couleur est le gage d’union; la matière pesante peut enrichir l’impondérable en manifestant d’une manière éclatante ce qui se dérobait en lui; l’obscurité, en faisant sortir les couleurs de la lumière, lui vaut, dans notre sphère, un joyeux triomphe; et la lumière en même temps, en s’unissant à la matière pesante dans la couleur, l’allège et l’idéalise: rien ne demeure stérile; tout fait œuvre de beauté. Les molécules dispersées dans l’air nous donnent les splendeurs du couchant; l’obscurité infinie des espaces vides, se répandant dans la clarté du jour, l’adoucit en une charmante teinte bleue; le mystère même de la nuit et la brutalité de la lumière, saisis au travers l’un de l’autre et l’un dans l’autre, conspirent à une merveilleuse douceur: le jour manifeste la nuit; car, plus la lumière est abondante et pure, plus le ciel est profond, et plus le regard devine l’immensité des espaces qui sont au delà; et le soir, quand le voile de clarté tombe pour laisser voir la nuit à découvert, on la trouverait bien vulgaire et bien triste, si elle ne s’emplissait lentement d’un autre mystère.

Devenue expressive dans la couleur, la lumière s’est rapprochée du son: elle peut concourir avec lui à manifester l’âme des choses; tandis qu’un son qui s’élèverait dans la pure clarté serait comme une voix dans le désert, sans rien qui la soutienne ou lui réponde, les sonorités du monde s’harmonisent à ses splendeurs. La magnificence ou la tristesse des teintes correspond à la plénitude joyeuse ou à la douceur voilée des sons: la lumière, dans sa lutte et son union avec l’obscurité, est devenue dramatique, et elle s’accorde avec un monde où tout est action; l’ombre, en pénétrant dans la clarté, y a glissé d’intimes trésors de mélancolie que le bleu pâlissant du soir communique à l’âme, et la sérénité impassible de la clarté pure est devenue, au contact de l’ombre qu’elle dissipe en s’y transformant, quelque chose de plus humain, la joie.

Jean Jaurès poésie

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive I-J, Jaurès, Jean

Karoline von Günderrode

(1780 – 1806)

Der Gefangene und der Sänger

Ich wallte mit leichtem und lustigem Sinn

Und singend am Kerker vorüber;

Da schallt aus der Tiefe, da schallt aus dem Thurm

Mir Stimme des Freundes herüber. –

„Ach Sänger! verweile, mich tröstet dein Lied,

Es steigt zum Gefangnen herunter,

Ihm macht es gesellig die einsame Zeit,

Das krankende Herz ihm gesunder.“

Ich horchte der Stimme, gehorchte ihr bald,

Zum Kerker hin wandt’ ich die Schritte,

Gern sprach ich die freundlichsten Worte hinab,

Begegnete jeglicher Bitte.

Da war dem Gefangenen freier der Sinn,

Gesellig die einsamen Stunden. –

„Gern gäb ich dir Lieber! so rief er: die Hand,

Doch ist sie von Banden umwunden.

Gern käm’ ich Geliebter! gern käm’ ich herauf

Am Herzen dich treulich zu herzen;

Doch trennen mich Mauern und Riegel von dir,

O fühl’ des Gefangenen Schmerzen.

Es ziehet mich mancherlei Sehnsucht zu dir;

Doch Ketten umfangen mein Leben,

Drum gehe mein Lieber und laß mich allein,

Ich Armer ich kann dir nichts geben.“ –

Da ward mir so weich und so wehe ums Herz,

Ich konnte den Lieben nicht lassen.

Am Kerker nun lausch’ ich von Frührothes Schein

Bis Abends die Farben erblassen.

Und harren dort werd’ ich die Jahre hindurch,

Und sollt’ ich drob selber erblassen.

Es ist mir so weich und so sehnend ums Herz

Ich kann den Geliebten nicht lassen.

Karoline Günderrode Gedichte

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive G-H, Karoline von Günderrode

Poison

Poison

by Katherine Mansfield

The post was very late. When we came back from our walk after lunch it still had not arrived.

“Pas encore, Madame,” sang Annette, scurrying back to her cooking.

We carried our parcels into the dining-room. The table was laid. As always, the sight of the table laid for two—for two people only—and yet so finished, so perfect, there was no possible room for a third, gave me a queer, quick thrill as though I’d been struck by that silver lightning that quivered over the white cloth, the brilliant glasses, the shallow bowl of freezias.

“Blow the old postman! Whatever can have happened to him?” said Beatrice. “Put those things down, dearest.”

“Where would you like them …?”

She raised her head; she smiled her sweet, teasing smile.

“Anywhere—Silly.”

But I knew only too well that there was no such place for her, and I would have stood holding the squat liqueur bottle and the sweets for months, for years, rather than risk giving another tiny shock to her exquisite sense of order.

“Here—I’ll take them.” She plumped them down on the table with her long gloves and a basket of figs. “The Luncheon Table. Short story by—by—” She took my arm. “Let’s go on to the terrace—” and I felt her shiver. “Ça sent,” she said faintly, “de la cuisine …”

I had noticed lately—we had been living in the south for two months—that when she wished to speak of food, or the climate, or, playfully, of her love for me, she always dropped into French.

We perched on the balustrade under the awning. Beatrice leaned over gazing down—down to the white road with its guard of cactus spears. The beauty of her ear, just her ear, the marvel of it was so great that I could have turned from regarding it to all that sweep of glittering sea below and stammered: “You know—her ear! She has ears that are simply the most …”

She was dressed in white, with pearls round her throat and lilies-of-the-valley tucked into her belt. On the third finger of her left hand she wore one pearl ring—no wedding ring.

“Why should I, mon ami? Why should we pretend? Who could possibly care?”

And of course I agreed, though privately, in the depths of my heart, I would have given my soul to have stood beside her in a large, yes, a large, fashionable church, crammed with people, with old reverend clergymen, with The Voice that breathed o’er Eden, with palms and the smell of scent, knowing there was a red carpet and confetti outside, and somewhere, a wedding-cake and champagne and a satin shoe to throw after the carriage—if I could have slipped our wedding-ring on to her finger.

Not because I cared for such horrible shows, but because I felt it might possibly perhaps lessen this ghastly feeling of absolute freedom, her absolute freedom, of course.

Oh, God! What torture happiness was—what anguish! I looked up at the villa, at the windows of our room hidden so mysteriously behind the green straw blinds. Was it possible that she ever came moving through the green light and smiling that secret smile, that languid, brilliant smile that was just for me? She put her arm round my neck; the other hand softly, terribly, brushed back my hair.

“Who are you?” Who was she? She was—Woman.

… On the first warm evening in Spring, when lights shone like pearls through the lilac air and voices murmured in the fresh-flowering gardens, it was she who sang in the tall house with the tulle curtains. As one drove in the moonlight through the foreign city hers was the shadow that fell across the quivering gold of the shutters. When the lamp was lighted, in the new-born stillness her steps passed your door. And she looked out into the autumn twilight, pale in her furs, as the automobile swept by …

In fact, to put it shortly, I was twenty-four at the time. And when she lay on her back, with the pearls slipped under her chin, and sighed “I’m thirsty, dearest. Donne-moi un orange,” I would gladly, willingly, have dived for an orange into the jaws of a crocodile—if crocodiles ate oranges.

“Had I two little feathery wings

And were a little feathery bird …”

sang Beatrice.

I seized her hand. “You wouldn’t fly away?”

“Not far. Not further than the bottom of the road.”

“Why on earth there?”

She quoted: “He cometh not, she said …”

“Who? The silly old postman? But you’re not expecting a letter.”

“No, but it’s maddening all the same. Ah!” Suddenly she laughed and leaned against me. “There he is—look—like a blue beetle.”

And we pressed our cheeks together and watched the blue beetle beginning to climb.

“Dearest,” breathed Beatrice. And the word seemed to linger in the air, to throb in the air like the note of a violin.

“What is it?”

“I don’t know,” she laughed softly. “A wave of—a wave of affection, I suppose.”

I put my arm round her. “Then you wouldn’t fly away?”

And she said rapidly and softly: “No! No! Not for worlds. Not really. I love this place. I’ve loved being here. I could stay here for years, I believe. I’ve never been so happy as I have these last two months, and you’ve been so perfect to me, dearest, in every way.”

This was such bliss—it was so extraordinary, so unprecedented, to hear her talk like this that I had to try to laugh it off.

“Don’t! You sound as if you were saying good-bye.”

“Oh, nonsense, nonsense. You mustn’t say such things even in fun!” She slid her little hand under my white jacket and clutched my shoulder. “You’ve been happy, haven’t you?”

“Happy? Happy? Oh, God—if you knew what I feel at this moment … Happy! My Wonder! My Joy!”

I dropped off the balustrade and embraced her, lifting her in my arms. And while I held her lifted I pressed my face in her breast and muttered: “You are mine?” And for the first time in all the desperate months I’d known her, even counting the last month of— surely—Heaven—I believed her absolutely when she answered:

“Yes, I am yours.”

The creak of the gate and the postman’s steps on the gravel drew us apart. I was dizzy for the moment. I simply stood there, smiling, I felt, rather stupidly. Beatrice walked over to the cane chairs.

“You go—go for the letters,” said she.

I—well—I almost reeled away. But I was too late. Annette came running. “Pas de lettres” said she.

My reckless smile in reply as she handed me the paper must have surprised her. I was wild with joy. I threw the paper up into the air and sang out:

“No letters, darling!” as I came over to where the beloved woman was lying in the long chair.

For a moment she did not reply. Then she said slowly as she tore off the newspaper wrapper: “The world forgetting, by the world forgot.”

There are times when a cigarette is just the very one thing that will carry you over the moment. It is more than a confederate, even; it is a secret, perfect little friend who knows all about it and understands absolutely. While you smoke you look down at it—smile or frown, as the occasion demands; you inhale deeply and expel the smoke in a slow fan. This was one of those moments. I walked over to the magnolia and breathed my fill of it. Then I came back and leaned over her shoulder. But quickly she tossed the paper away on to the stone.

“There’s nothing in it,” said she. “Nothing. There’s only some poison trial. Either some man did or didn’t murder his wife, and twenty thousand people have sat in court every day and two million words have been wired all over the world after each proceeding.”

“Silly world!” said I, flinging into another chair. I wanted to forget the paper, to return, but cautiously, of course, to that moment before the postman came. But when she answered I knew from her voice the moment was over for now. Never mind. I was content to wait—five hundred years, if need be—now that I knew.

“Not so very silly,” said Beatrice. “After all it isn’t only morbid curiosity on the part of the twenty thousand.”

“What is it, darling?” Heavens knows I didn’t care.

“Guilt! “she cried. “Guilt! Didn’t you realise that? They’re fascinated like sick people are fascinated by anything—any scrap of news about their own case. The man in the dock may be innocent enough, but the people in court are nearly all of them poisoners. Haven’t you ever thought” —she was pale with excitement— “of the amount of poisoning that goes on? It’s the exception to find married people who don’t poison each other— married people and lovers. Oh,” she cried, “the number of cups of tea, glasses of wine, cups of coffee that are just tainted. The number I’ve had myself, and drunk, either knowing or not knowing—and risked it. The only reason why so many couples”—she laughed—” survive, is because the one is frightened of giving the other the fatal dose. That dose takes nerve! But it’s bound to come sooner or later. There’s no going back once the first little dose has been given. It’s the beginning of the end, really—don’t you agree? Don’t you see what I mean?”

She didn’t wait for me to answer. She unpinned the lilies-of-the-valley and lay back, drawing them across her eyes.

“Both my husbands poisoned me,” said Beatrice. “My first husband gave me a huge dose almost immediately, but my second was really an artist in his way. Just a tiny pinch, now and again, cleverly disguised—Oh, so cleverly! —until one morning I woke up and in every single particle of me, to the ends of my fingers and toes, there was a tiny grain. I was just in time …”

I hated to hear her mention her husbands so calmly, especially to-day. It hurt. I was going to speak, but suddenly she cried mournfully:

“Why! Why should it have happened to me? What have I done? Why have I been all my life singled out by … It’s a conspiracy.”

I tried to tell her it was because she was too perfect for this horrible world—too exquisite, too fine. It frightened people. I made a little joke.

“But I—I haven’t tried to poison you.”

Beatrice gave a queer small laugh and bit the end of a lily stem.

“You!” said she. “You wouldn’t hurt a fly!”

Strange. That hurt, though. Most horribly.

Just then Annette ran out with our apéritifs. Beatrice leaned forward and took a glass from the tray and handed it to me. I noticed the gleam of the pearl on what I called her pearl finger. How could I be hurt at what she said?

“And you,” I said, taking the glass, “you’ve never poisoned anybody.”

That gave me an idea; I tried to explain.

“You—you do just the opposite. What is the name for one like you who, instead of poisoning people, fills them—everybody, the postman, the man who drives us, our boatman, the flower-seller, me—with new life, with something of her own radiance, her beauty, her—”

Dreamily she smiled; dreamily she looked at me.

“What are you thinking of—my lovely darling?”

“I was wondering,” she said, “whether, after lunch, you’d go down to the post-office and ask for the afternoon letters. Would you mind, dearest? Not that I’m expecting one —but—I just thought, perhaps—it’s silly not to have the letters if they’re there. Isn’t it? Silly to wait till to-morrow.” She twirled the stem of the glass in her fingers. Her beautiful head was bent. But I lifted my glass and drank, sipped rather—sipped slowly, deliberately, looking at that dark head and thinking of—postmen and blue beetles and farewells that were not farewells and …

Good God! Was it fancy? No, it wasn’t fancy. The drink tasted chill, bitter, queer.

Poison

by Katherine Mansfield (1888 – 1923)

From: Something Childish and Other Stories

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive M-N, Katherine Mansfield, Mansfield, Katherine

Sibylla Schwarz

(1621 – 1638)

Cloris

Cloris

deine rohte Wangen

deiner Augen helles Licht

und dein Purpurangesicht

hält mich nuhn nicht mehr gefangen.

Ich kan nicht mehr an dir hangen

weil du dich erbarmest nicht

ob mir schon mein Hertze bricht;

deiner schnöden Hoffart Prangen

und dein hönisches Gemüht

krencket mir mein jung Geblüht

daß ich dich wil gerne meiden

wan mich meine Galate

die mir macht dis süße Weh

wil in ihren Diensten leiden.

Sibylla Schwarz poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, SIbylla Schwarz

An Unfinished Story

An Unfinished Story

by O. Henry

We no longer groan and heap ashes upon our heads when the flames of Tophet are mentioned. For, even the preachers have begun to tell us that God is radium, or ether or some scientific compound, and that the worst we wicked ones may expect is a chemical reaction. This is a pleasing hypothesis; but there lingers yet some of the old, goodly terror of orthodoxy.

There are but two subjects upon which one may discourse with a free imagination, and without the possibility of being controverted. You may talk of your dreams; and you may tell what you heard a parrot say. Both Morpheus and the bird are incompetent witnesses; and your listener dare not attack your recital. The baseless fabric of a vision, then, shall furnish my theme—chosen with apologies and regrets instead of the more limited field of Pretty Polly’s small talk.

I had a dream that was so far removed from the higher criticism that it had to do with the ancient, respectable, and lamented bar-of-judgment theory.

Gabriel had played his trump; and those of us who could not follow suit were arraigned for examination. I noticed at one side a gathering of professional bondsmen in solemn black and collars that buttoned behind; but it seemed there was some trouble about their real estate titles; and they did not appear to be getting any of us out.

A fly cop—an angel policeman—flew over to me and took me by the left wing. Near at hand was a group of very prosperous-looking spirits arraigned for judgment.

“Do you belong with that bunch?” the policeman asked.

“Who are they?” was my answer.

“Why,” said he, “they are—”

But this irrelevant stuff is taking up space that the story should occupy.

Dulcie worked in a department store. She sold Hamburg edging, or stuffed peppers, or automobiles, or other little trinkets such as they keep in department stores. Of what she earned, Dulcie received six dollars per week. The remainder was credited to her and debited to somebody else’s account in the ledger kept by G—Oh, primal energy, you say, Reverend Doctor—Well then, in the Ledger of Primal Energy.

During her first year in the store, Dulcie was paid five dollars per week. It would be instructive to know how she lived on that amount. Don’t care? Very well; probably you are interested in larger amounts. Six dollars is a larger amount. I will tell you how she lived on six dollars per week.

One afternoon at six, when Dulcie was sticking her hat-pin within an eighth of an inch of her medulla oblongata, she said to her chum, Sadie—the girl that waits on you with her left side:

“Say, Sade, I made a date for dinner this evening with Piggy.”

“You never did!” exclaimed Sadie admiringly. “Well, ain’t you the lucky one? Piggy’s an awful swell; and he always takes a girl to swell places. He took Blanche up to the Hoffman House one evening, where they have swell music, and you see a lot of swells. You’ll have a swell time, Dulcie.”

Dulcie hurried off homeward. Her eyes were shining, and her cheeks showed the delicate pink of life’s—real life’s—approaching dawn. It was Friday; and she had fifty cents of her last week’s wages.

The streets were filled with the rush-hour floods of people. The electric lights of Broadway were glowing—calling moths from miles, from leagues, from hundreds of leagues out of darkness around to come in and attend the singeing school. Men in accurate clothes, with faces like those carved on cherry-stones.

O. Henry

(1862 – 1910)

An Unfinished Story

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive G-H, Henry, O.

The Alchemist

The Alchemist

by H. P. Lovecraft

High up, crowning the grassy summit of a swelling mound whose sides are wooded near the base with the gnarled trees of the primeval forest, stands the old chateau of my ancestors. For centuries its lofty battlements have frowned down upon the wild and rugged countryside about, serving as a home and stronghold for the proud house whose honoured line is older even than the moss-grown castle walls. These ancient turrets, stained by the storms of generations and crumbling under the slow yet mighty pressure of time, formed in the ages of feudalism one of the most dreaded and formidable fortresses in all France. From its machicolated parapets and mounted battlements Barons, Counts, and even Kings had been defied, yet never had its spacious halls resounded to the footsteps of the invader.

But since those glorious years all is changed. A poverty but little above the level of dire want, together with a pride of name that forbids its alleviation by the pursuits of commercial life, have prevented the scions of our line from maintaining their estates in pristine splendour; and the falling stones of the walls, the overgrown vegetation in the parks, the dry and dusty moat, the ill-paved courtyards, and toppling towers without, as well as the sagging floors, the worm-eaten wainscots, and the faded tapestries within, all tell a gloomy tale of fallen grandeur. As the ages passed, first one, then another of the four great turrets were left to ruin, until at last but a single tower housed the sadly reduced descendants of the once mighty lords of the estate.

It was in one of the vast and gloomy chambers of this remaining tower that I, Antoine, last of the unhappy and accursed Comtes de C——, first saw the light of day, ninety long years ago. Within these walls, and amongst the dark and shadowy forests, the wild ravines and grottoes of the hillside below, were spent the first years of my troubled life. My parents I never knew. My father had been killed at the age of thirty-two, a month before I was born, by the fall of a stone somehow dislodged from one of the deserted parapets of the castle; and my mother having died at my birth, my care and education devolved solely upon one remaining servitor, an old and trusted man of considerable intelligence, whose name I remember as Pierre. I was an only child, and the lack of companionship which this fact entailed upon me was augmented by the strange care exercised by my aged guardian in excluding me from the society of the peasant children whose abodes were scattered here and there upon the plains that surround the base of the hill. At the time, Pierre said that this restriction was imposed upon me because my noble birth placed me above association with such plebeian company. Now I know that its real object was to keep from my ears the idle tales of the dread curse upon our line, that were nightly told and magnified by the simple tenantry as they conversed in hushed accents in the glow of their cottage hearths.

Thus isolated, and thrown upon my own resources, I spent the hours of my childhood in poring over the ancient tomes that filled the shadow-haunted library of the chateau, and in roaming without aim or purpose through the perpetual dusk of the spectral wood that clothes the side of the hill near its foot. It was perhaps an effect of such surroundings that my mind early acquired a shade of melancholy. Those studies and pursuits which partake of the dark and occult in Nature most strongly claimed my attention.

Of my own race I was permitted to learn singularly little, yet what small knowledge of it I was able to gain, seemed to depress me much. Perhaps it was at first only the manifest reluctance of my old preceptor to discuss with me my paternal ancestry that gave rise to the terror which I ever felt at the mention of my great house; yet as I grew out of childhood, I was able to piece together disconnected fragments of discourse, let slip from the unwilling tongue which had begun to falter in approaching senility, that had a sort of relation to a certain circumstance which I had always deemed strange, but which now became dimly terrible. The circumstance to which I allude is the early age at which all the Comtes of my line had met their end. Whilst I had hitherto considered this but a natural attribute of a family of short-lived men, I afterward pondered long upon these premature deaths, and began to connect them with the wanderings of the old man, who often spoke of a curse which for centuries had prevented the lives of the holders of my title from much exceeding the span of thirty-two years. Upon my twenty-first birthday, the aged Pierre gave to me a family document which he said had for many generations been handed down from father to son, and continued by each possessor. Its contents were of the most startling nature, and its perusal confirmed the gravest of my apprehensions. At this time, my belief in the supernatural was firm and deep-seated, else I should have dismissed with scorn the incredible narrative unfolded before my eyes.

The paper carried me back to the days of the thirteenth century, when the old castle in which I sat had been a feared and impregnable fortress. It told of a certain ancient man who had once dwelt on our estates, a person of no small accomplishments, though little above the rank of peasant; by name, Michel, usually designated by the surname of Mauvais, the Evil, on account of his sinister reputation. He had studied beyond the custom of his kind, seeking such things as the Philosopher’s Stone, or the Elixir of Eternal Life, and was reputed wise in the terrible secrets of Black Magic and Alchemy. Michel Mauvais had one son, named Charles, a youth as proficient as himself in the hidden arts, and who had therefore been called Le Sorcier, or the Wizard. This pair, shunned by all honest folk, were suspected of the most hideous practices. Old Michel was said to have burnt his wife alive as a sacrifice to the Devil, and the unaccountable disappearances of many small peasant children were laid at the dreaded door of these two. Yet through the dark natures of the father and the son ran one redeeming ray of humanity; the evil old man loved his offspring with fierce intensity, whilst the youth had for his parent a more than filial affection.

One night the castle on the hill was thrown into the wildest confusion by the vanishment of young Godfrey, son to Henri the Comte. A searching party, headed by the frantic father, invaded the cottage of the sorcerers and there came upon old Michel Mauvais, busy over a huge and violently boiling cauldron. Without certain cause, in the ungoverned madness of fury and despair, the Comte laid hands on the aged wizard, and ere he released his murderous hold his victim was no more. Meanwhile joyful servants were proclaiming the finding of young Godfrey in a distant and unused chamber of the great edifice, telling too late that poor Michel had been killed in vain. As the Comte and his associates turned away from the lowly abode of the alchemists, the form of Charles Le Sorcier appeared through the trees. The excited chatter of the menials standing about told him what had occurred, yet he seemed at first unmoved at his father’s fate. Then, slowly advancing to meet the Comte, he pronounced in dull yet terrible accents the curse that ever afterward haunted the house of C——.

“May ne’er a noble of thy murd’rous line

Survive to reach a greater age than thine!”

spake he, when, suddenly leaping backwards into the black wood, he drew from his tunic a phial of colourless liquid which he threw into the face of his father’s slayer as he disappeared behind the inky curtain of the night. The Comte died without utterance, and was buried the next day, but little more than two and thirty years from the hour of his birth. No trace of the assassin could be found, though relentless bands of peasants scoured the neighbouring woods and the meadow-land around the hill.

Thus time and the want of a reminder dulled the memory of the curse in the minds of the late Comte’s family, so that when Godfrey, innocent cause of the whole tragedy and now bearing the title, was killed by an arrow whilst hunting, at the age of thirty-two, there were no thoughts save those of grief at his demise. But when, years afterward, the next young Comte, Robert by name, was found dead in a nearby field from no apparent cause, the peasants told in whispers that their seigneur had but lately passed his thirty-second birthday when surprised by early death. Louis, son to Robert, was found drowned in the moat at the same fateful age, and thus down through the centuries ran the ominous chronicle; Henris, Roberts, Antoines, and Armands snatched from happy and virtuous lives when little below the age of their unfortunate ancestor at his murder.

That I had left at most but eleven years of further existence was made certain to me by the words which I read. My life, previously held at small value, now became dearer to me each day, as I delved deeper and deeper into the mysteries of the hidden world of black magic. Isolated as I was, modern science had produced no impression upon me, and I laboured as in the Middle Ages, as wrapt as had been old Michel and young Charles themselves in the acquisition of daemonological and alchemical learning. Yet read as I might, in no manner could I account for the strange curse upon my line. In unusually rational moments, I would even go so far as to seek a natural explanation, attributing the early deaths of my ancestors to the sinister Charles Le Sorcier and his heirs; yet having found upon careful inquiry that there were no known descendants of the alchemist, I would fall back to occult studies, and once more endeavour to find a spell that would release my house from its terrible burden. Upon one thing I was absolutely resolved. I should never wed, for since no other branches of my family were in existence, I might thus end the curse with myself.

As I drew near the age of thirty, old Pierre was called to the land beyond. Alone I buried him beneath the stones of the courtyard about which he had loved to wander in life. Thus was I left to ponder on myself as the only human creature within the great fortress, and in my utter solitude my mind began to cease its vain protest against the impending doom, to become almost reconciled to the fate which so many of my ancestors had met. Much of my time was now occupied in the exploration of the ruined and abandoned halls and towers of the old chateau, which in youth fear had caused me to shun, and some of which, old Pierre had once told me, had not been trodden by human foot for over four centuries. Strange and awesome were many of the objects I encountered. Furniture, covered by the dust of ages and crumbling with the rot of long dampness, met my eyes. Cobwebs in a profusion never before seen by me were spun everywhere, and huge bats flapped their bony and uncanny wings on all sides of the otherwise untenanted gloom.

Of my exact age, even down to days and hours, I kept a most careful record, for each movement of the pendulum of the massive clock in the library told off so much more of my doomed existence. At length I approached that time which I had so long viewed with apprehension. Since most of my ancestors had been seized some little while before they reached the exact age of Comte Henri at his end, I was every moment on the watch for the coming of the unknown death. In what strange form the curse should overtake me, I knew not; but I was resolved, at least, that it should not find me a cowardly or a passive victim. With new vigour I applied myself to my examination of the old chateau and its contents.

It was upon one of the longest of all my excursions of discovery in the deserted portion of the castle, less than a week before that fatal hour which I felt must mark the utmost limit of my stay on earth, beyond which I could have not even the slightest hope of continuing to draw breath, that I came upon the culminating event of my whole life. I had spent the better part of the morning in climbing up and down half-ruined staircases in one of the most dilapidated of the ancient turrets. As the afternoon progressed, I sought the lower levels, descending into what appeared to be either a mediaeval place of confinement, or a more recently excavated storehouse for gunpowder. As I slowly traversed the nitre-encrusted passageway at the foot of the last staircase, the paving became very damp, and soon I saw by the light of my flickering torch that a blank, water-stained wall impeded my journey. Turning to retrace my steps, my eye fell upon a small trap-door with a ring, which lay directly beneath my feet. Pausing, I succeeded with difficulty in raising it, whereupon there was revealed a black aperture, exhaling noxious fumes which caused my torch to sputter, and disclosing in the unsteady glare the top of a flight of stone steps. As soon as the torch, which I lowered into the repellent depths, burned freely and steadily, I commenced my descent. The steps were many, and led to a narrow stone-flagged passage which I knew must be far underground. The passage proved of great length, and terminated in a massive oaken door, dripping with the moisture of the place, and stoutly resisting all my attempts to open it. Ceasing after a time my efforts in this direction, I had proceeded back some distance toward the steps, when there suddenly fell to my experience one of the most profound and maddening shocks capable of reception by the human mind. Without warning, I heard the heavy door behind me creak slowly open upon its rusted hinges. My immediate sensations are incapable of analysis. To be confronted in a place as thoroughly deserted as I had deemed the old castle with evidence of the presence of man or spirit, produced in my brain a horror of the most acute description. When at last I turned and faced the seat of the sound, my eyes must have started from their orbits at the sight that they beheld. There in the ancient Gothic doorway stood a human figure. It was that of a man clad in a skull-cap and long mediaeval tunic of dark colour. His long hair and flowing beard were of a terrible and intense black hue, and of incredible profusion. His forehead, high beyond the usual dimensions; his cheeks, deep-sunken and heavily lined with wrinkles; and his hands, long, claw-like, and gnarled, were of such a deathly, marble-like whiteness as I have never elsewhere seen in man. His figure, lean to the proportions of a skeleton, was strangely bent and almost lost within the voluminous folds of his peculiar garment. But strangest of all were his eyes; twin caves of abysmal blackness, profound in expression of understanding, yet inhuman in degree of wickedness. These were now fixed upon me, piercing my soul with their hatred, and rooting me to the spot whereon I stood. At last the figure spoke in a rumbling voice that chilled me through with its dull hollowness and latent malevolence. The language in which the discourse was clothed was that debased form of Latin in use amongst the more learned men of the Middle Ages, and made familiar to me by my prolonged researches into the works of the old alchemists and daemonologists. The apparition spoke of the curse which had hovered over my house, told me of my coming end, dwelt on the wrong perpetrated by my ancestor against old Michel Mauvais, and gloated over the revenge of Charles Le Sorcier. He told how the young Charles had escaped into the night, returning in after years to kill Godfrey the heir with an arrow just as he approached the age which had been his father’s at his assassination; how he had secretly returned to the estate and established himself, unknown, in the even then deserted subterranean chamber whose doorway now framed the hideous narrator; how he had seized Robert, son of Godfrey, in a field, forced poison down his throat, and left him to die at the age of thirty-two, thus maintaining the foul provisions of his vengeful curse. At this point I was left to imagine the solution of the greatest mystery of all, how the curse had been fulfilled since that time when Charles Le Sorcier must in the course of Nature have died, for the man digressed into an account of the deep alchemical studies of the two wizards, father and son, speaking most particularly of the researches of Charles Le Sorcier concerning the elixir which should grant to him who partook of it eternal life and youth.

His enthusiasm had seemed for the moment to remove from his terrible eyes the hatred that had at first so haunted them, but suddenly the fiendish glare returned, and with a shocking sound like the hissing of a serpent, the stranger raised a glass phial with the evident intent of ending my life as had Charles Le Sorcier, six hundred years before, ended that of my ancestor. Prompted by some preserving instinct of self-defence, I broke through the spell that had hitherto held me immovable, and flung my now dying torch at the creature who menaced my existence. I heard the phial break harmlessly against the stones of the passage as the tunic of the strange man caught fire and lit the horrid scene with a ghastly radiance. The shriek of fright and impotent malice emitted by the would-be assassin proved too much for my already shaken nerves, and I fell prone upon the slimy floor in a total faint.

When at last my senses returned, all was frightfully dark, and my mind remembering what had occurred, shrank from the idea of beholding more; yet curiosity overmastered all. Who, I asked myself, was this man of evil, and how came he within the castle walls? Why should he seek to avenge the death of poor Michel Mauvais, and how had the curse been carried on through all the long centuries since the time of Charles Le Sorcier? The dread of years was lifted from my shoulders, for I knew that he whom I had felled was the source of all my danger from the curse; and now that I was free, I burned with the desire to learn more of the sinister thing which had haunted my line for centuries, and made of my own youth one long-continued nightmare. Determined upon further exploration, I felt in my pockets for flint and steel, and lit the unused torch which I had with me. First of all, the new light revealed the distorted and blackened form of the mysterious stranger. The hideous eyes were now closed. Disliking the sight, I turned away and entered the chamber beyond the Gothic door. Here I found what seemed much like an alchemist’s laboratory. In one corner was an immense pile of a shining yellow metal that sparkled gorgeously in the light of the torch. It may have been gold, but I did not pause to examine it, for I was strangely affected by that which I had undergone. At the farther end of the apartment was an opening leading out into one of the many wild ravines of the dark hillside forest. Filled with wonder, yet now realising how the man had obtained access to the chateau, I proceeded to return. I had intended to pass by the remains of the stranger with averted face, but as I approached the body, I seemed to hear emanating from it a faint sound, as though life were not yet wholly extinct. Aghast, I turned to examine the charred and shrivelled figure on the floor. Then all at once the horrible eyes, blacker even than the seared face in which they were set, opened wide with an expression which I was unable to interpret. The cracked lips tried to frame words which I could not well understand. Once I caught the name of Charles Le Sorcier, and again I fancied that the words “years” and “curse” issued from the twisted mouth. Still I was at a loss to gather the purport of his disconnected speech. At my evident ignorance of his meaning, the pitchy eyes once more flashed malevolently at me, until, helpless as I saw my opponent to be, I trembled as I watched him.

Suddenly the wretch, animated with his last burst of strength, raised his hideous head from the damp and sunken pavement. Then, as I remained, paralysed with fear, he found his voice and in his dying breath screamed forth those words which have ever afterward haunted my days and my nights. “Fool,” he shrieked, “can you not guess my secret? Have you no brain whereby you may recognise the will which has through six long centuries fulfilled the dreadful curse upon your house? Have I not told you of the great elixir of eternal life? Know you not how the secret of Alchemy was solved? I tell you, it is I! I! I! that have lived for six hundred years to maintain my revenge, FOR I AM CHARLES LE SORCIER!”

The Alchemist (1908)

by H. P. Lovecraft (1890 – 1937)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive K-L, Lovecraft, H.P., Tales of Mystery & Imagination

William Shakespeare

(1564-1616)

O, now, for ever

O, now, for ever

Farewell the tranquil mind! farewell content!

Farewell the plumed troop and the big wars

That make ambition virtue! O, farewell!

Farewell the neighing steed and the shrill trump,

The spirit-stirring drum, the ear-piercing fife,

The royal banner, and all quality,

Pride, pomp, and circumstance of glorious war!

And, O you mortal engines, whose rude throats

The immortal Jove’s dread clamours counterfeit,

Farewell! Othello’s occupation’s gone!

William Shakespeare, “Othello”, Act 3 scene 3

Shakespeare 400 (1616 – 2016)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Shakespeare, William

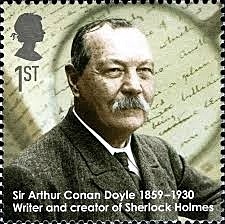

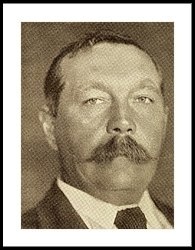

Round the Red Lamp: Being Facts and Fancies of Medical Life by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle

Table of Contents

The Preface

Behind the Times. (#01)

His First Operation. (#02)

A Straggler of ‘15. (#03)

The Third Generation. (#04)

A False Start. (#05)

The Curse of Eve. (#06)

Sweethearts. (#07)

A Physiologist’s Wife. (#08)

The Case of Lady Sannox. (#09)

A Question of Diplomacy. (#10)

A Medical Document. (#11)

Lot No. 249. (#12)

The Los Amigos Fiasco. (#13)

The Doctors of Hoyland. (#14)

The Surgeon Talks. (#15)

The Preface.

[Being an extract from a long and animated correspondence with a friend in America.]

I quite recognise the force of your objection that an invalid or a woman in weak health would get no good from stories which attempt to treat some features of medical life with a certain amount of realism. If you deal with this life at all, however, and if you are anxious to make your doctors something more than marionettes, it is quite essential that you should paint the darker side, since it is that which is principally presented to the surgeon or physician. He sees many beautiful things, it is true, fortitude and heroism, love and self-sacrifice; but they are all called forth (as our nobler qualities are always called forth) by bitter sorrow and trial. One cannot write of medical life and be merry over it.

Then why write of it, you may ask? If a subject is painful why treat it at all? I answer that it is the province of fiction to treat painful things as well as cheerful ones. The story which wiles away a weary hour fulfils an obviously good purpose, but not more so, I hold, than that which helps to emphasise the graver side of life. A tale which may startle the reader out of his usual grooves of thought, and shocks him into seriousness, plays the part of the alterative and tonic in medicine, bitter to the taste but bracing in the result. There are a few stories in this little collection which might have such an effect, and I have so far shared in your feeling that I have reserved them from serial publication. In book-form the reader can see that they are medical stories, and can, if he or she be so minded, avoid them.

Yours very truly,

A. CONAN DOYLE

P.S.—You ask about the Red Lamp. It is the usual sign of the general practitioner in England.

Behind the Times

Behind the Times

by Arthur Conan Doyle

My first interview with Dr. James Winter was under dramatic circumstances. It occurred at two in the morning in the bedroom of an old country house. I kicked him twice on the white waistcoat and knocked off his gold spectacles, while he with the aid of a female accomplice stifled my angry cries in a flannel petticoat and thrust me into a warm bath. I am told that one of my parents, who happened to be present, remarked in a whisper that there was nothing the matter with my lungs. I cannot recall how Dr. Winter looked at the time, for I had other things to think of, but his description of my own appearance is far from flattering. A fluffy head, a body like a trussed goose, very bandy legs, and feet with the soles turned inwards—those are the main items which he can remember.

From this time onwards the epochs of my life were the periodical assaults which Dr. Winter made upon me. He vaccinated me; he cut me for an abscess; he blistered me for mumps. It was a world of peace and he the one dark cloud that threatened. But at last there came a time of real illness—a time when I lay for months together inside my wickerwork-basket bed, and then it was that I learned that that hard face could relax, that those country-made creaking boots could steal very gently to a bedside, and that that rough voice could thin into a whisper when it spoke to a sick child.

And now the child is himself a medical man, and yet Dr. Winter is the same as ever. I can see no change since first I can remember him, save that perhaps the brindled hair is a trifle whiter, and the huge shoulders a little more bowed. He is a very tall man, though he loses a couple of inches from his stoop. That big back of his has curved itself over sick beds until it has set in that shape. His face is of a walnut brown, and tells of long winter drives over bleak country roads, with the wind and the rain in his teeth. It looks smooth at a little distance, but as you approach him you see that it is shot with innumerable fine wrinkles like a last year’s apple. They are hardly to be seen when he is in repose; but when he laughs his face breaks like a starred glass, and you realise then that though he looks old, he must be older than he looks.

How old that is I could never discover. I have often tried to find out, and have struck his stream as high up as George IV and even the Regency, but without ever getting quite to the source. His mind must have been open to impressions very early, but it must also have closed early, for the politics of the day have little interest for him, while he is fiercely excited about questions which are entirely prehistoric. He shakes his head when he speaks of the first Reform Bill and expresses grave doubts as to its wisdom, and I have heard him, when he was warmed by a glass of wine, say bitter things about Robert Peel and his abandoning of the Corn Laws. The death of that statesman brought the history of England to a definite close, and Dr. Winter refers to everything which had happened since then as to an insignificant anticlimax.

But it was only when I had myself become a medical man that I was able to appreciate how entirely he is a survival of a past generation. He had learned his medicine under that obsolete and forgotten system by which a youth was apprenticed to a surgeon, in the days when the study of anatomy was often approached through a violated grave. His views upon his own profession are even more reactionary than in politics. Fifty years have brought him little and deprived him of less. Vaccination was well within the teaching of his youth, though I think he has a secret preference for inoculation. Bleeding he would practise freely but for public opinion. Chloroform he regards as a dangerous innovation, and he always clicks with his tongue when it is mentioned. He has even been known to say vain things about Laennec, and to refer to the stethoscope as “a new-fangled French toy.” He carries one in his hat out of deference to the expectations of his patients, but he is very hard of hearing, so that it makes little difference whether he uses it or not.

He reads, as a duty, his weekly medical paper, so that he has a general idea as to the advance of modern science. He always persists in looking upon it as a huge and rather ludicrous experiment. The germ theory of disease set him chuckling for a long time, and his favourite joke in the sick room was to say, “Shut the door or the germs will be getting in.” As to the Darwinian theory, it struck him as being the crowning joke of the century. “The children in the nursery and the ancestors in the stable,” he would cry, and laugh the tears out of his eyes.

He is so very much behind the day that occasionally, as things move round in their usual circle, he finds himself, to his bewilderment, in the front of the fashion. Dietetic treatment, for example, had been much in vogue in his youth, and he has more practical knowledge of it than any one whom I have met. Massage, too, was familiar to him when it was new to our generation. He had been trained also at a time when instruments were in a rudimentary state, and when men learned to trust more to their own fingers. He has a model surgical hand, muscular in the palm, tapering in the fingers, “with an eye at the end of each.” I shall not easily forget how Dr. Patterson and I cut Sir John Sirwell, the County Member, and were unable to find the stone. It was a horrible moment. Both our careers were at stake. And then it was that Dr. Winter, whom we had asked out of courtesy to be present, introduced into the wound a finger which seemed to our excited senses to be about nine inches long, and hooked out the stone at the end of it. “It’s always well to bring one in your waistcoat-pocket,” said he with a chuckle, “but I suppose you youngsters are above all that.”

We made him president of our branch of the British Medical Association, but he resigned after the first meeting. “The young men are too much for me,” he said. “I don’t understand what they are talking about.” Yet his patients do very well. He has the healing touch—that magnetic thing which defies explanation or analysis, but which is a very evident fact none the less. His mere presence leaves the patient with more hopefulness and vitality. The sight of disease affects him as dust does a careful housewife. It makes him angry and impatient. “Tut, tut, this will never do!” he cries, as he takes over a new case. He would shoo Death out of the room as though he were an intrusive hen. But when the intruder refuses to be dislodged, when the blood moves more slowly and the eyes grow dimmer, then it is that Dr. Winter is of more avail than all the drugs in his surgery. Dying folk cling to his hand as if the presence of his bulk and vigour gives them more courage to face the change; and that kindly, windbeaten face has been the last earthly impression which many a sufferer has carried into the unknown.

When Dr. Patterson and I—both of us young, energetic, and up-to-date—settled in the district, we were most cordially received by the old doctor, who would have been only too happy to be relieved of some of his patients. The patients themselves, however, followed their own inclinations—which is a reprehensible way that patients have—so that we remained neglected, with our modern instruments and our latest alkaloids, while he was serving out senna and calomel to all the countryside. We both of us loved the old fellow, but at the same time, in the privacy of our own intimate conversations, we could not help commenting upon this deplorable lack of judgment. “It’s all very well for the poorer people,” said Patterson. “But after all the educated classes have a right to expect that their medical man will know the difference between a mitral murmur and a bronchitic rale. It’s the judicial frame of mind, not the sympathetic, which is the essential one.”

I thoroughly agreed with Patterson in what he said. It happened, however, that very shortly afterwards the epidemic of influenza broke out, and we were all worked to death. One morning I met Patterson on my round, and found him looking rather pale and fagged out. He made the same remark about me. I was, in fact, feeling far from well, and I lay upon the sofa all the afternoon with a splitting headache and pains in every joint. As evening closed in, I could no longer disguise the fact that the scourge was upon me, and I felt that I should have medical advice without delay. It was of Patterson, naturally, that I thought, but somehow the idea of him had suddenly become repugnant to me. I thought of his cold, critical attitude, of his endless questions, of his tests and his tappings. I wanted something more soothing—something more genial.

“Mrs. Hudson,” said I to my housekeeper, “would you kindly run along to old Dr. Winter and tell him that I should be obliged to him if he would step round?”

She was back with an answer presently. “Dr. Winter will come round in an hour or so, sir; but he has just been called in to attend Dr. Patterson.”

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (1859 – 1930)

Round the Red Lamp: Being Facts and Fancies of Medical Life

Behind the Times. (#01)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Doyle, Arthur Conan, Doyle, Arthur Conan, DRUGS & DISEASE & MEDICINE & LITERATURE, Round the Red Lamp

Max Jacob

(1876 – 1944)

La Guerre

Quand le soleil est en colère,

les vagues de la mer vont plus vite,

les nuages du ciel se dépêchent.

Les yeux du

Sage s’exorbitent

le nombril de

Bouddha était

comme une coupe vide : la coupe maintenant

déborde

Max Jacob poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive I-J, Jacob, Max

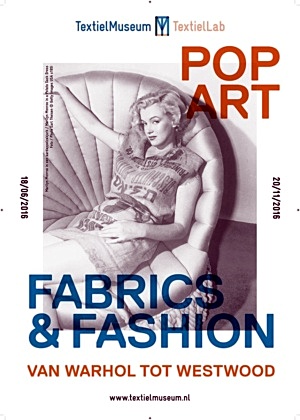

In de jaren ‘50 verovert een golf van rock-‘n-roll en jeugdcultuur uit Amerika de wereld. De mix van populaire beelden en muziek met kunst en mode verandert de manier waarop mensen gekleed gaan. Veel jonge ontwerpers maken, geïnspireerd door popart, spannende nieuwe patronen voor textiel en behang. Zelfs gerenommeerde popart kunstenaars als Andy Warhol en internationaal geprezen modeontwerpers als Mary Quant, Pierre Cardin en Vivienne Westwood ontwerpen spectaculair ‘pop’-textiel voor mode en in huis. Van dessins met rocksterren en ‘soup cans’ tot psychedelische patronen en punkoutfits van de sixties en seventies; vooral bij een avontuurlijke jongere generatie vinden zij gretig aftrek.

In de jaren ‘50 verovert een golf van rock-‘n-roll en jeugdcultuur uit Amerika de wereld. De mix van populaire beelden en muziek met kunst en mode verandert de manier waarop mensen gekleed gaan. Veel jonge ontwerpers maken, geïnspireerd door popart, spannende nieuwe patronen voor textiel en behang. Zelfs gerenommeerde popart kunstenaars als Andy Warhol en internationaal geprezen modeontwerpers als Mary Quant, Pierre Cardin en Vivienne Westwood ontwerpen spectaculair ‘pop’-textiel voor mode en in huis. Van dessins met rocksterren en ‘soup cans’ tot psychedelische patronen en punkoutfits van de sixties en seventies; vooral bij een avontuurlijke jongere generatie vinden zij gretig aftrek.

De tentoonstelling ‘Pop Art Fabrics & Fashion’ laat meer dan tweehonderd textiel- en modeontwerpen zien, vanaf de geboorte van de popcultuur in 1956 tot haar roerige ondergang in de loop van de jaren ‘70.

Hoogtepunten zijn items als de ‘Potato Sack’, waarin Marilyn Monroe werd gespot, recent ontdekte dessins van Andy Warhol, ‘Space Age’ textiel van Paco Rabanne, ‘Op Art’ outfits van Mary Quant, items uit Elton Johns persoonlijke garderobe en de shocking shirts van Vivienne Westwood.

Popcultuur

Na de Tweede Wereldoorlog bloeit de levendige ‘pop’-cultuur onder jongeren in Noord-Amerika en Europa. Ontstaan buiten de gevestigde orde, manifesteert ‘Pop’ zich als een kleurrijke uitbarsting van rock-‘n-roll-muziek, mode en kunst. De cultuur kenmerkt zich door een veelheid aan gelaagde beelden en symboliek. Die beelden zijn volop aanwezig in het dagelijks leven. Ze zijn bekend via de reclame- en verpakkingsindustrie, billboardkunst, cartoons, stripboeken en via de film- en popwereld.

Het is voor het eerst dat tieners herkenbaar zijn als een op zichzelf staande groep. Zij durven taboes aan de kaak te stellen en hun kwetsbaarheid te tonen. Daarmee wijzen ze de traditionele normen en waarden van volwassenen af. Ze onderscheiden zich met een nieuwe stijl in kleding en woninginrichting, die in niets lijkt op de stijl van hun ouders.

‘Pop’-ontwerpers

Veel jonge, getalenteerde mode- en textielontwerpers uit de jaren ‘60 laten zich inspireren door de popart esthetiek en maken originele ontwerpen. Zelfs popart kunstenaars met de status van Andy Warhol verdienen hun geld met textielontwerpen. Recent zijn enkele van de dessins van deze toonaangevende grafisch ontwerper uit het naoorlogse New York herontdekt. Zij worden nu voor het eerst getoond. Ook zijn stoffen te zien van Nicky Zann, de gevierde stripboekauteur uit New York. Zijn opvallende textielontwerpen hebben veel gemeen met het werk van popart kunstenaar Roy Lichtenstein. Lichtenstein gebruikte op zijn beurt strips en cartoons van deze toonaangevende grafisch ontwerper als voornaamste inspiratiebron voor zijn kunstwerken. Van de rock-‘n-roll tot de punk uit het midden van de jaren ‘70 is de symbiotische relatie tussen ‘pop’-textiel, ‘pop’-mode en popart onmiskenbaar.

‘Op Art’ en ‘Space Age’

Er is echter meer te beleven tijdens de jaren ‘60 dan alleen op popart geïnspireerde textiel en mode. Rond 1965 maken de Britse modeontwerpster Mary Quant en de Franse couturiers Pierre Cardin, André Courrèges en Paco Rabanne grote indruk met hun geometrische ontwerpen en gebruik van plastic als nieuw materiaal. De stromingen, waartoe hun werk wordt gerekend, ‘Op Art’ en ‘Space Age’ styling, vallend onder de generieke term ‘pop’. Ook werk van deze ontwerpers is in de tentoonstelling te zien.

Punk en New Wave

In de jaren ‘70 start Vivienne Westwood haar carrière in Londen. Haar baanbrekende ‘Punk’-ontwerpen en het radicaal nieuw gebruik van stoffen veroorzaken een revolutie in de modewereld. Het ontwerpen van ‘pop’-textiel bereikt in deze jaren zijn hoogtepunt, maar tegelijkertijd wordt het einde ervan ingeluid. Met het voortschrijden van het ‘pop’-tijdperk, gaan jongeren zich radicaal anders kleden. Hun nieuwe stijl past beter bij de relaxte, antiautoritaire en gelijkwaardige manier waarop zij in het leven staan. Dé iconen van deze stijl zijn het T-shirt en de spijkerbroek. Daarmee heb je eindeloze mogelijkheden om te laten zien waar je voor staat. De tentoonstelling toont een aantal prachtige T-shirts, met afbeeldingen van David Bowie en de rock- en punkzanger Iggy Pop, uit het ‘Punk’-tijdperk van de Britse beeldhouwer John Dove en zijn vrouw, de textielontwerpster Molly White. Hun werk uit de jaren ‘70 tilt het ontwerpen van T-shirts naar het niveau van moderne kunst.

Popart in het TextielMuseum

Met ingang van de zomer zal het TextielMuseum in het teken staan van popart. Rondom de tentoonstelling worden er verschillende activiteiten georganiseerd rond het thema popart. Gezinnen met kinderen kunnen op onderzoek gaan in de tentoonstelling of samen het ProefLab ontdekken. Voor volwassen en professionals is er een uitgebreid programma met rondleidingen, workshops en masterclasses.

Pop Art Fabrics & Fashion – van Warhol tot Westwood

Nog te zien t/m 20 november 2016 in Textielmuseum Tilburg.

TextielMuseum

Goirkestraat 96

5046 GN Tilburg

Telefoon: 013 536 74 75

(Van dinsdag tot en met vrijdag 10.00 tot 17.00 uur)

# Meer info op website Textielmuseum Tilburg

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Andy Warhol, Art & Literature News, David Bowie, Design, Illustrators, Illustration, Pop Art

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature