Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Rainer Maria Rilke

(1875 – 1926)

Mädchenklage

Diese Neigung, in den Jahren,

da wir alle Kinder waren,

viel allein zu sein, war mild;

andern ging die Zeit im Streite,

und man hatte seine Seite,

seine Nähe, seine Weite,

einen Weg, ein Tier, ein Bild.

Und ich dachte noch, das Leben

hörte niemals auf zu geben,

daß man sich in sich besinnt.

Bin ich in mir nicht im Größten?

Will mich meines nicht mehr trösten

und verstehen wie als Kind?

Plötzlich bin ich wie verstoßen,

und zu einem Übergroßen

wird mir diese Einsamkeit,

wenn, auf meiner Brüste Hügeln

stehend, mein Gefühl nach Flügeln

oder einem Ende schreit.

Rainer Maria Rilke Gedichte

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive Q-R, Rilke, Rainer Maria

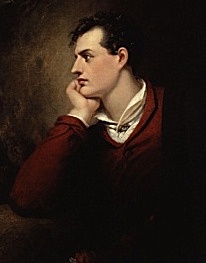

Lord Byron

I Watched Thee

I watched thee when the foe was at our side

Ready to strike at him, or thee and me

Were safety hopeless rather than divide

Aught with one loved, save love and liberty.

I watched thee in the breakers when the rock

Received our prow and all was storm and fear

And bade thee cling to me through every shock

This arm would be thy bark or breast thy bier.

I watched thee when the fever glazed thine eyes

Yielding my couch, and stretched me on the ground

When overworn with watching, ne’er to rise

From thence, if thou an early grave hadst found.

The Earthquake came and rocked the quivering wall

And men and Nature reeled as if with wine

Whom did I seek around the tottering Hall

For thee, whose safety first provide for thine.

And when convulsive throes denied my breath

The faintest utterance to my fading thought

To thee, to thee, even in the grasp of death

My spirit turned. Ah! oftener than it ought.

Thus much and more, and yet thou lov’st me not,

And never wilt, Love dwells not in our will

Nor can I blame thee, though it be my lot

To strongly, wrongly, vainly, love thee still.

Lord George Gordon Noel Byron (1788 – 1824)

I Watched Thee

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Byron, Lord

Nieuwe namen voor festivalzaterdag van Tilt: Herman Brusselmans, Akwasi, Menno Wigman en meer

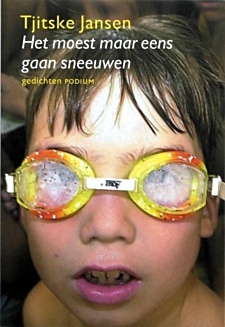

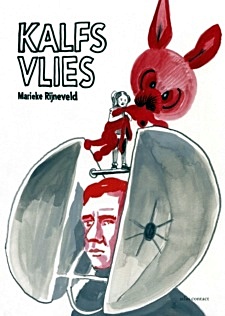

Nog een maand tot het Tilt Festival 2017. De hoogste tijd om een aantal nieuwe namen te presenteren. Niemand minder dan Herman Brusselmans, Menno Wigman, #DE16VAN, Martin Beversluis, Tjitske Jansen, Marieke Rijneveld, Carmien Michels, Jeroen Thijssen en Betonfraktion, De Baron, Zwart Licht en DJ St. Paul treden op tijdens de festivalzaterdag in Theater De NWE Vorst.

Herman Brusselmans Revue

Hij is een van de meest controversiële schrijvers van Vlaa nderen. Herman Brusselmans (1957) trekt een breed publiek, schrijft zich suf en is een  performer die houdt van niet-alledaagse dingen. Daarom presenteert hij de Herman Brusselmans Revue op Tilt. Drie kunstenaars spelen een passage uit zijn werk. Literatuur over drank, seks en verveling, maar dan vertaald in dans, muziek en toneel. Op geheel eigen wijze voorziet Brusselmans de passages van commentaar.

performer die houdt van niet-alledaagse dingen. Daarom presenteert hij de Herman Brusselmans Revue op Tilt. Drie kunstenaars spelen een passage uit zijn werk. Literatuur over drank, seks en verveling, maar dan vertaald in dans, muziek en toneel. Op geheel eigen wijze voorziet Brusselmans de passages van commentaar.

Menno Wigman

Menno Wigman (1966) debuteerde als dichter op zijn achttiende. Hij schreef bundels, gaf een literair eenmanstijdschrift uit, drumde in een punkband en grossierde in bizarre pseudoniemen. Inmiddels is hij van de gevestigde orde: Jan Campertprijs, talloze publicaties, volop vertaald, Stadsdichter van Amsterdam. E n nu komt hij naar Tilt voor een voordacht en interview.

#DE16VAN

Op Tilt is het eerste live-event van de online serie #DE16VAN te zien; een concept van rapper Akwasi op het YouTube kanaal van zijn eigen label ‘Neerlands Dope’. #DE16VAN is een wekelijkse serie waar muzikanten, mensen vanuit het theater en creatievelingen 16 zinnen voor de mic spitten, zeggen of zingen. Akwasi zelf startte de 25-delige reeks, op Tilt treden er 6 bekende muzikale en literaire fenomenen op.

Poëzieprogramma

Poëzieprogramma

Het is een traditie op Tilt: Martin Beversluis (1972), Stadsdichter van Tilburg, die zijn eigen programma samenstelt. Met deze editie: Tjitske Jansen (1971) met haar succesvolle mix van poëzie, proza en theater, Marieke Rijneveld (1991) winnares van de C. Buddingh’-prijs voor beste poëziedebuut en – volgens De Volkskrant – hét literaire talent van 2016. En Carmien Michels (1990) komt, Vlaams woordkunstenares en regerend Nederlands Kampioen Poetry Slam.

Muzikale optredens van o.a. Zwart Licht en St. Paul

Muziek komt van historicus, schrijver en journalist Jeroen Thijssen met de band Betonfraktion. Nederlandstalige Rock-Extravaganza De Baron brengt verhalen over reizen, heimwee en over De Baron. De hiphopgroep Zwart Licht (met frontman Akwasi, ook bekend van zijn label Neerlands Dope en als gastheer bij De Wereld Draait Door) komt, versterkt door bliksemsnelle Nederrap. DJ St. Paul, vaste prik op Tilt, sluit de avond af met een set vol pop, soul, indie, hiphop, electronica en rock ‘n roll.

Het Tilt Festival is in zeven jaar uitgegroeid tot het grootste literaire festival in het zuiden van Nederland. Zowel landelijk als regionaal talent krijgt de kans om zichzelf te ontwikkelen en zich te presenteren aan het publiek op diverse culturele locaties in de historische Willem II Straat in Tilburg.

# Meer informatie via website festival tilt

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Art & Literature News, Beversluis, Martin, Herman Brusselmans, Jansen, Tjitske, Literary Events, MUSIC, Rijneveld, Marieke Lucas, Swarth, Nick J., THEATRE, Tilt Festival Tilburg, Wigman, Menno

Robert Bridges

My delight and thy delight

My delight and thy delight

Walking, like two angels white,

In the gardens of the night:

My desire and thy desire

Twinning to a tongue of fire,

Leaping live, and laughing higher;

Thro’ the everlasting strife

In the mystery of life.

Love, from whom the world begun,

Hath the secret of the sun.

Love can tell and love alone,

Whence the million stars are strewn,

Why each atom knows its own,

How, in spite of woe and death,

Gay is life, and sweet is breath:

This he taught us, this we knew,

Happy in his science true,

Hand in hand as we stood

‘Neath the shadows of the wood,

Heart to heart as we lay

In the dawning of the day.

Robert Seymour Bridges (1844 – 1930)

My delight and thy delight

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Bridges, Robert

Sibylla Schwarz

Sonnet

(Daphne aus der Schäfererzählung: Faunus)

Hier hab ich nun mein sehnliches Verlangen:

hier liegt mein Lieb, hier ligt mein ander ich:

hier giebt das Glück sich selbst gefangen mich:

hier mag ich nun mein Lieb vielmahl umfangen:

hier mag ich nun auch küssen seine Wangen:

Cupido hört mein Klagen inniglich,

und wil nun auch so hülffreich zeigen sich;

Nun mag ich wohl mit meinem Glücke prangen;

die Venus zeigt mir iezt ein guhtes Ziel,

ich wil nur selbst, nicht was ich gerne wil;

O Blödigkeit, du must nur von mir weichen!

weil du hir bist, wärt meine grosse Pein;

Wer lieben wil, mus nicht so blöde seyn,

sonst kan er nicht der Liebe Lohn erreichen.

Sibylla Schwarz (1621 – 1638)

Gedicht: Sonnet

(Daphne aus der Schäfererzählung: Faunus)

(Blödigkeit bedeutet Schüchternheit)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, SIbylla Schwarz

INCUBATE ♦ cutting edge festival in Tilburg ♦ will not continue in 2017

Incubate is heavily disappointed by the decision of the Municipality of Tilburg to not provide any more funding in 2017. This news comes after the Province of Noord-Brabant already cut funding for the coming four years. The organisation finds it financially irresponsible to continue and will therefore cease its activities.

“Incubate is proud to have been able to create a festival with exciting, creative, cutting-edge arts in the past 13 years, together with its 500+ volunteers and partners. We have thus inspired many other musicians, artists, organisers and other festivals, and we hope that they use some of that impact for their own future,” said Miriam van Ommeren and Arthur Janssen on behalf of Incubate.

13 years of Incubate

Over the past 13 years, Incubate has become one of the leading multidisciplinary festivals in Europe. It was and still is internationally acclaimed by press, artists and visitors. Incubate was the first Dutch festival to bring artists such as Psychic TV, Pauline Oliveros, Sun Ra Arkestra, Fields of the Nephilim, James Blake and Cabaret Voltaire to the Netherlands and to create a platform for themes such as piracy in the arts, public participation, and innovation. It was the first to invite speakers like Charles Leadbeater, Simon Reynolds and Andrew Keen and internationally renowned artists such as Hermann Nitsch, Santiago Sierra, Wendy White and Ryan Trecartin to Tilburg, connecting them with local emerging artists.

Social impact

The festival instigated both social and artistic debate. Throughout the years, it provided a space for thousands of artists and tens of thousands of visitors from more than 48 countries. Many of them visited Tilburg for the very first time, and kept coming back. The wider public has become acquainted with the festival through remarkable projects in public spaces, for instance the more than hundred pianos from British artist Luke Jerram, the thousands of portraits of mothers in the city in cooperation with French artist JR and the activities around Iconostase 180, a sculpture by renowned architect Yona Friedman, which took place last Summer. These projects brought the entire city into contact with avant-garde art and culture.

New model in 2016

In 2015, a financial deficit was supplemented by the Province of Noord-Brabant and the Municipality of Tilburg, on specific conditions to the organisation. All these conditions have been met in 2016: three successful editions of Incubate took place in this year, with good results on an artistic, organisational and financial level. Both audience and press were positive about the new direction: just this week, the festival was added to the list of 50 most important festivals of the Netherlands by 3voor12, a Dutch music platform.

The organisation deeply regrets that, through this decision, Tilburg will lose a unique festival of international standing. This will certainly have an adverse effect on the conditions and opportunities in Tilburg for young artists, emerging bands, recently graduated filmmakers and game developers and progressive, culture-loving citizens. The organisation entreats that the Municipality of Tilburg will use the now available funds as designated; to provide substantial and accessible art and culture in the city and the wider region. Although there will no longer be a festival held by the organisation, the foundation will continue to exist for now.

February 23, 2017

Stadsdichter van Tilburg =

Martin Beversluis: Requiem

Aan Incubate

We reden op fietsen van licht

en geluid door de stad we gaven

onze varkens een S van stro

vlekkie en spekkie aten het gulzig

we koesterden de foto’s van onze

moeders die niet weg mochten

waaien nooit weg konden waaien

een festival werd langzaamaan

gesloopt door bureaucraten er

stonden piano’s op straat die

zeiden bespeel me want ik ben

van jou er was controverse

zoals er ook altijd ontroering

was er waren polsbandjes er

was een stad voor vriendelijke

mensen van heinde en verre

waar je broedplaatsen moest

koesteren want die waren je

toekomst stad van makers in

een land van slopers die hun

mouwen stropen en opgaan

voor moord de raad vraagt

om een nekschot maar de

wethouder zegt ik wurg

de makers zien de leegte

komen en benoemen deze

stad heet vanaf nu Stilburg

Martin Beversluis

Feb. 2017

# Meer info op website incubate

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: # Music Archive, Archive A-B, Art & Literature News, Beversluis, Martin, MUSIC, THEATRE

A Medical Document

by Arthur Conan Doyle

Medical men are, as a class, very much too busy to take stock of singular situations or dramatic events. Thus it happens that the ablest chronicler of their experiences in our literature was a lawyer. A life spent in watching over death-beds — or over birth-beds which are infinitely more trying — takes something from a man’s sense of proportion, as constant strong waters might corrupt his palate. The overstimulated nerve ceases to respond. Ask the surgeon for his best experiences and he may reply that he has seen little that is remarkable, or break away into the technical. But catch him some night when the fire has spurted up and his pipe is reeking, with a few of his brother practitioners for company and an artful question or allusion to set him going. Then you will get some raw, green facts new plucked from the tree of life.

It is after one of the quarterly dinners of the Midland Branch of the British Medical Association. Twenty coffee cups, a dozer liqueur glasses, and a solid bank of blue smoke which swirls slowly along the high, gilded ceiling gives a hint of a successful gathering. But the members have shredded off to their homes. The line of heavy, bulge-pocketed overcoats and of stethoscope- bearing top hats is gone from the hotel corridor. Round the fire in the sitting- room three medicos are still lingering, however, all smoking and arguing, while a fourth, who is a mere layman and young at that, sits back at the table. Under cover of an open journal he is writing furiously with a stylographic pen, asking a question in an innocent voice from time to time and so flickering up the conversation whenever it shows a tendency to wane.

The three men are all of that staid middle age which begins early and lasts late in the profession. They are none of them famous, yet each is of good repute, and a fair type of his particular branch. The portly man with the authoritative manner and the white, vitriol splash upon his cheek is Charley Manson, chief of the Wormley Asylum, and author of the brilliant monograph—Obscure Nervous Lesions in the Unmarried. He always wears his collar high like that, since the half-successful attempt of a student of Revelations to cut his throat with a splinter of glass. The second, with the ruddy face and the merry brown eyes, is a general practitioner, a man of vast experience, who, with his three assistants and his five horses, takes twenty-five hundred a year in half-crown visits and shilling consultations out of the poorest quarter of a great city. That cheery face of Theodore Foster is seen at the side of a hundred sick-beds a day, and if he has one-third more names on his visiting list than in his cash book he always promises himself that he will get level some day when a millionaire with a chronic complaint—the ideal combination—shall seek his services. The third, sitting on the right with his dress shoes shining on the top of the fender, is Hargrave, the rising surgeon. His face has none of the broad humanity of Theodore Foster’s, the eye is stern and critical, the mouth straight and severe, but there is strength and decision in every line of it, and it is nerve rather than sympathy which the patient demands when he is bad enough to come to Hargrave’s door. He calls himself a jawman “a mere jawman” as he modestly puts it, but in point of fact he is too young and too poor to confine himself to a specialty, and there is nothing surgical which Hargrave has not the skill and the audacity to do.

“Before, after, and during,” murmurs the general practitioner in answer to some interpolation of the outsider’s. “I assure you, Manson, one sees all sorts of evanescent forms of madness.”

“Ah, puerperal!” throws in the other, knocking the curved grey ash from his cigar. “But you had some case in your mind, Foster.”

“Well, there was only one last week which was new to me. I had been engaged by some people of the name of Silcoe. When the trouble came round I went myself, for they would not hear of an assistant. The husband who was a policeman, was sitting at the head of the bed on the further side. ‘This won’t do,’ said I. ‘Oh yes, doctor, it must do,’ said she. ‘It’s quite irregular and he must go,’ said I. ‘It’s that or nothing,’ said she. ‘I won’t open my mouth or stir a finger the whole night,’ said he. So it ended by my allowing him to remain, and there he sat for eight hours on end. She was very good over the matter, but every now and again HE would fetch a hollow groan, and I noticed that he held his right hand just under the sheet all the time, where I had no doubt that it was clasped by her left. When it was all happily over, I looked at him and his face was the colour of this cigar ash, and his head had dropped on to the edge of the pillow. Of course I thought he had fainted with emotion, and I was just telling myself what I thought of myself for having been such a fool as to let him stay there, when suddenly I saw that the sheet over his hand was all soaked with blood; I whisked it down, and there was the fellow’s wrist half cut through. The woman had one bracelet of a policeman’s handcuff over her left wrist and the other round his right one. When she had been in pain she had twisted with all her strength and the iron had fairly eaten into the bone of the man’s arm. ‘Aye, doctor,’ said she, when she saw I had noticed it. ‘He’s got to take his share as well as me. Turn and turn,’ said she.”

“Don’t you find it a very wearing branch of the profession?” asks Foster after a pause.

“My dear fellow, it was the fear of it that drove me into lunacy work.”

“Aye, and it has driven men into asylums who never found their way on to the medical staff. I was a very shy fellow myself as a student, and I know what it means.”

“No joke that in general practice,” says the alienist.

“Well, you hear men talk about it as though it were, but I tell you it’s much nearer tragedy. Take some poor, raw, young fellow who has just put up his plate in a strange town. He has found it a trial all his life, perhaps, to talk to a woman about lawn tennis and church services. When a young man IS shy he is shyer than any girl. Then down comes an anxious mother and consults him upon the most intimate family matters. ‘I shall never go to that doctor again,’ says she afterwards. ‘His manner is so stiff and unsympathetic.’ Unsympathetic! Why, the poor lad was struck dumb and paralysed. I have known general practitioners who were so shy that they could not bring themselves to ask the way in the street. Fancy what sensitive men like that must endure before they get broken in to medical practice. And then they know that nothing is so catching as shyness, and that if they do not keep a face of stone, their patient will be covered with confusion. And so they keep their face of stone, and earn the reputation perhaps of having a heart to correspond. I suppose nothing would shake YOUR nerve, Manson.”

“Well, when a man lives year in year out among a thousand lunatics, with a fair sprinkling of homicidals among them, one’s nerves either get set or shattered. Mine are all right so far.”

“I was frightened once,” says the surgeon. “It was when I was doing dispensary work. One night I had a call from some very poor people, and gathered from the few words they said that their child was ill. When I entered the room I saw a small cradle in the corner. Raising the lamp I walked over and putting back the curtains I looked down at the baby. I tell you it was sheer Providence that I didn’t drop that lamp and set the whole place alight. The head on the pillow turned and I saw a face looking up at me which seemed to me to have more malignancy and wickedness than ever I had dreamed of in a nightmare. It was the flush of red over the cheekbones, and the brooding eyes full of loathing of me, and of everything else, that impressed me. I’ll never forget my start as, instead of the chubby face of an infant, my eyes fell upon this creature. I took the mother into the next room. ‘What is it?’ I asked. ‘A girl of sixteen,’ said she, and then throwing up her arms, ‘Oh, pray God she may be taken!’ The poor thing, though she spent her life in this little cradle, had great, long, thin limbs which she curled up under her. I lost sight of the case and don’t know what became of it, but I’ll never forget the look in her eyes.”

“That’s creepy,” says Dr. Foster. “But I think one of my experiences would run it close. Shortly after I put up my plate I had a visit from a little hunch-backed woman who wished me to come and attend to her sister in her trouble. When I reached the house, which was a very poor one, I found two other little hunched-backed women, exactly like the first, waiting for me in the sitting-room. Not one of them said a word, but my companion took the lamp and walked upstairs with her two sisters behind her, and me bringing up the rear. I can see those three queer shadows cast by the lamp upon the wall as clearly as I can see that tobacco pouch. In the room above was the fourth sister, a remarkably beautiful girl in evident need of my assistance. There was no wedding ring upon her finger. The three deformed sisters seated themselves round the room, like so many graven images, and all night not one of them opened her mouth. I’m not romancing, Hargrave; this is absolute fact. In the early morning a fearful thunderstorm broke out, one of the most violent I have ever known. The little garret burned blue with the lightning, and thunder roared and rattled as if it were on the very roof of the house. It wasn’t much of a lamp I had, and it was a queer thing when a spurt of lightning came to see those three twisted figures sitting round the walls, or to have the voice of my patient drowned by the booming of the thunder. By Jove! I don’t mind telling you that there was a time when I nearly bolted from the room. All came right in the end, but I never heard the true story of the unfortunate beauty and her three crippled sisters.”

“That’s the worst of these medical stories,” sighs the outsider. “They never seem to have an end.”

“When a man is up to his neck in practice, my boy, he has no time to gratify his private curiosity. Things shoot across him and he gets a glimpse of them, only to recall them, perhaps, at some quiet moment like this. But I’ve always felt, Manson, that your line had as much of the terrible in it as any other.”

“More,” groans the alienist. “A disease of the body is bad enough, but this seems to be a disease of the soul. Is it not a shocking thing—a thing to drive a reasoning man into absolute Materialism—to think that you may have a fine, noble fellow with every divine instinct and that some little vascular change, the dropping, we will say, of a minute spicule of bone from the inner table of his skull on to the surface of his brain may have the effect of changing him to a filthy and pitiable creature with every low and debasing tendency? What a satire an asylum is upon the majesty of man, and no less upon the ethereal nature of the soul.”

“Faith and hope,” murmurs the general practitioner.

“I have no faith, not much hope, and all the charity I can afford,” says the surgeon. “When theology squares itself with the facts of life I’ll read it up.”

“You were talking about cases,” says the outsider, jerking the ink down into his stylographic pen.

“Well, take a common complaint which kills many thousands every year, like G. P. for instance.”

“What’s G. P.?”

“General practitioner,” suggests the surgeon with a grin.

“The British public will have to know what G. P. is,” says the alienist gravely. “It’s increasing by leaps and bounds, and it has the distinction of being absolutely incurable. General paralysis is its full title, and I tell you it promises to be a perfect scourge. Here’s a fairly typical case now which I saw last Monday week. A young farmer, a splendid fellow, surprised his fellows by taking a very rosy view of things at a time when the whole country-side was grumbling. He was going to give up wheat, give up arable land, too, if it didn’t pay, plant two thousand acres of rhododendrons and get a monopoly of the supply for Covent Garden—there was no end to his schemes, all sane enough but just a bit inflated. I called at the farm, not to see him, but on an altogether different matter. Something about the man’s way of talking struck me and I watched him narrowly. His lip had a trick of quivering, his words slurred themselves together, and so did his handwriting when he had occasion to draw up a small agreement. A closer inspection showed me that one of his pupils was ever so little larger than the other. As I left the house his wife came after me. ‘Isn’t it splendid to see Job looking so well, doctor,’ said she; ‘he’s that full of energy he can hardly keep himself quiet.’ I did not say anything, for I had not the heart, but I knew that the fellow was as much condemned to death as though he were lying in the cell at Newgate. It was a characteristic case of incipient G. P.”

“Good heavens!” cries the outsider. “My own lips tremble. I often slur my words. I believe I’ve got it myself.”

Three little chuckles come from the front of the fire.

“There’s the danger of a little medical knowledge to the layman.”

“A great authority has said that every first year’s student is suffering in silent agony from four diseases,” remarks the surgeon. ” One is heart disease, of course; another is cancer of the parotid. I forget the two other.”

“Where does the parotid come in?”

“Oh, it’s the last wisdom tooth coming through!”

“And what would be the end of that young farmer?” asks the outsider.

“Paresis of all the muscles, ending in fits, coma, and death. It may be a few months, it may be a year or two. He was a very strong young man and would take some killing.”

“By-the-way,” says the alienist, “did I ever tell you about the first certificate I signed? I came as near ruin then as a man could go.”

“What was it, then?”

“I was in practice at the time. One morning a Mrs. Cooper called upon me and informed me that her husband had shown signs of delusions lately. They took the form of imagining that he had been in the army and had distinguished himself very much. As a matter of fact he was a lawyer and had never been out of England. Mrs. Cooper was of opinion that if I were to call it might alarm him, so it was agreed between us that she should send him up in the evening on some pretext to my consulting-room, which would give me the opportunity of having a chat with him and, if I were convinced of his insanity, of signing his certificate. Another doctor had already signed, so that it only needed my concurrence to have him placed under treatment. Well, Mr. Cooper arrived in the evening about half an hour before I had expected him, and consulted me as to some malarious symptoms from which he said that he suffered. According to his account he had just returned from the Abyssinian Campaign, and had been one of the first of the British forces to enter Magdala. No delusion could possibly be more marked, for he would talk of little else, so I filled in the papers without the slightest hesitation. When his wife arrived, after he had left, I put some questions to her to complete the form. ‘What is his age?’ I asked. ‘Fifty,’ said she. ‘Fifty!’ I cried. ‘Why, the man I examined could not have been more than thirty! And so it came out that the real Mr. Cooper had never called upon me at all, but that by one of those coincidences which take a man’s breath away another Cooper, who really was a very distinguished young officer of artillery, had come in to consult me. My pen was wet to sign the paper when I discovered it,” says Dr. Manson, mopping his forehead.

“We were talking about nerve just now,” observes the surgeon. “Just after my qualifying I served in the Navy for a time, as I think you know. I was on the flag-ship on the West African Station, and I remember a singular example of nerve which came to my notice at that time. One of our small gunboats had gone up the Calabar river, and while there the surgeon died of coast fever. On the same day a man’s leg was broken by a spar falling upon it, and it became quite obvious that it must be taken off above the knee if his life was to be saved. The young lieutenant who was in charge of the craft searched among the dead doctor’s effects and laid his hands upon some chloroform, a hip-joint knife, and a volume of Grey’s Anatomy. He had the man laid by the steward upon the cabin table, and with a picture of a cross section of the thigh in front of him he began to take off the limb. Every now and then, referring to the diagram, he would say: ‘Stand by with the lashings, steward. There’s blood on the chart about here.’ Then he would jab with his knife until he cut the artery, and he and his assistant would tie it up before they went any further. In this way they gradually whittled the leg off, and upon my word they made a very excellent job of it. The man is hopping about the Portsmouth Hard at this day.

“It’s no joke when the doctor of one of these isolated gunboats himself falls ill,” continues the surgeon after a pause. “You might think it easy for him to prescribe for himself, but this fever knocks you down like a club, and you haven’t strength left to brush a mosquito off your face. I had a touch of it at Lagos, and I know what I am telling you. But there was a chum of mine who really had a curious experience. The whole crew gave him up, and, as they had never had a funeral aboard the ship, they began rehearsing the forms so as to be ready. They thought that he was unconscious, but he swears he could hear every word that passed. ‘Corpse comin’ up the latchway!’ cried the Cockney sergeant of Marines. ‘Present harms!’ He was so amused, and so indignant too, that he just made up his mind that he wouldn’t be carried through that hatchway, and he wasn’t, either.”

“There’s no need for fiction in medicine,” remarks Foster, “for the facts will always beat anything you can fancy. But it has seemed to me sometimes that a curious paper might be read at some of these meetings about the uses of medicine in popular fiction.”

“How?”

“Well, of what the folk die of, and what diseases are made most use of in novels. Some are worn to pieces, and others, which are equally common in real life, are never mentioned. Typhoid is fairly frequent, but scarlet fever is unknown. Heart disease is common, but then heart disease, as we know it, is usually the sequel of some foregoing disease, of which we never hear anything in the romance. Then there is the mysterious malady called brain fever, which always attacks the heroine after a crisis, but which is unknown under that name to the text books. People when they are over-excited in novels fall down in a fit. In a fairly large experience I have never known anyone do so in real life. The small complaints simply don’t exist. Nobody ever gets shingles or quinsy, or mumps in a novel. All the diseases, too, belong to the upper part of the body. The novelist never strikes below the belt.”

“Well, of what the folk die of, and what diseases are made most use of in novels. Some are worn to pieces, and others, which are equally common in real life, are never mentioned. Typhoid is fairly frequent, but scarlet fever is unknown. Heart disease is common, but then heart disease, as we know it, is usually the sequel of some foregoing disease, of which we never hear anything in the romance. Then there is the mysterious malady called brain fever, which always attacks the heroine after a crisis, but which is unknown under that name to the text books. People when they are over-excited in novels fall down in a fit. In a fairly large experience I have never known anyone do so in real life. The small complaints simply don’t exist. Nobody ever gets shingles or quinsy, or mumps in a novel. All the diseases, too, belong to the upper part of the body. The novelist never strikes below the belt.”

“I’ll tell you what, Foster,” says the alienist, there is a side of life which is too medical for the general public and too romantic for the professional journals, but which contains some of the richest human materials that a man could study. It’s not a pleasant side, I am afraid, but if it is good enough for Providence to create, it is good enough for us to try and understand. It would deal with strange outbursts of savagery and vice in the lives of the best men, curious momentary weaknesses in the record of the sweetest women, known but to one or two, and inconceivable to the world around. It would deal, too, with the singular phenomena of waxing and of waning manhood, and would throw a light upon those actions which have cut short many an honoured career and sent a man to a prison when he should have been hurried to a consulting-room. Of all evils that may come upon the sons of men, God shield us principally from that one!”

“I had a case some little time ago which was out of the ordinary,” says the surgeon. “There’s a famous beauty in London society—I mention no names—who used to be remarkable a few seasons ago for the very low dresses which she would wear. She had the whitest of skins and most beautiful of shoulders, so it was no wonder. Then gradually the frilling at her neck lapped upwards and upwards, until last year she astonished everyone by wearing quite a high collar at a time when it was completely out of fashion. Well, one day this very woman was shown into my consulting-room. When the footman was gone she suddenly tore off the upper part of her dress. ‘For Gods sake do something for me!’ she cried. Then I saw what the trouble was. A rodent ulcer was eating its way upwards, coiling on in its serpiginous fashion until the end of it was flush with her collar. The red streak of its trail was lost below the line of her bust. Year by year it had ascended and she had heightened her dress to hide it, until now it was about to invade her face. She had been too proud to confess her trouble, even to a medical man.”

“And did you stop it?”

“Well, with zinc chloride I did what I could. But it may break out again. She was one of those beautiful white-and-pink creatures who are rotten with struma. You may patch but you can’t mend.”

“Dear! dear! dear!” cries the general practitioner, with that kindly softening of the eyes which had endeared him to so many thousands. “I suppose we mustn’t think ourselves wiser than Providence, but there are times when one feels that something is wrong in the scheme of things. I’ve seen some sad things in my life. Did I ever tell you that case where Nature divorced a most loving couple? He was a fine young fellow, an athlete and a gentleman, but he overdid athletics. You know how the force that controls us gives us a little tweak to remind us when we get off the beaten track. It may be a pinch on the great toe if we drink too much and work too little. Or it may be a tug on our nerves if we dissipate energy too much. With the athlete, of course, it’s the heart or the lungs. He had bad phthisis and was sent to Davos. Well, as luck would have it, she developed rheumatic fever, which left her heart very much affected. Now, do you see the dreadful dilemma in which those poor people found themselves? When he came below four thousand feet or so, his symptoms became terrible. She could come up about twenty-five hundred and then her heart reached its limit. They had several interviews half way down the valley, which left them nearly dead, and at last, the doctors had to absolutely forbid it. And so for four years they lived within three miles of each other and never met. Every morning he would go to a place which overlooked the chalet in which she lived and would wave a great white cloth and she answer from below. They could see each other quite plainly with their field glasses, and they might have been in different planets for all their chance of meeting.”

“And one at last died,” says the outsider.

“No, sir. I’m sorry not to be able to clinch the story, but the man recovered and is now a successful stockbroker in Drapers Gardens. The woman, too, is the mother of a considerable family. But what are you doing there?”

“Only taking a note or two of your talk.”

The three medical men laugh as they walk towards their overcoats.

“Why, we’ve done nothing but talk shop,” says the general practitioner. “What possible interest can the public take in that?”

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (1859 – 1930)

Round the Red Lamp: Being Facts and Fancies of Medical Life

A Medical Document (#11)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Doyle, Arthur Conan, Doyle, Arthur Conan, DRUGS & DISEASE & MEDICINE & LITERATURE, Round the Red Lamp

![]()

Video installatie L.A. Raeven in Museum Arnhem

Nog te zien t.m. 5 maart 2017

In Wild Zone 3 staat opnieuw de maakbaarheid van het lichaam centraal. De opname voor de nieuwe productie vond plaats in de koepelzaal van Museum Arnhem en wordt hier eveneens voor het eerst getoond. Museum Arnhem organiseerde in 2010 L.A. Raevens succesvolle reizende tentoonstelling Ideal individuals.

In Wild Zone 3 ensceneert L.A. Raeven het uiterlijk en de bewegingen van een groep kinderen en jongeren. Door de overeenkomst in hun uiterlijk wordt de suggestie gewekt dat het om leden van een androgyne sekte gaat; de jongeren zijn extreem lang, dragen dezelfde kleding en onduidelijk is of het om jongens of meisjes gaat. Het duo schetst een soort vrijplaats voor jongeren die de toeschouwer angst inboezemen omdat ze ‘anders’ zijn. De jongeren conformeren zich niet aan heersende opvattingen over vrouwelijkheid en mannelijkheid, en lijken zich voor altijd in een adolescente fase te bevinden.

Wild Zone 3 is een vervolg op Wild Zone 1 (2001) en Wild Zone 2 (2002) , de video-installaties waarin L.A. Raeven een ‘staat van zijn’ creëerden, en, zonder plot, twee gelijkende, nauwelijks bewegende individuen filmden. Wild Zone 3 komt voort uit de fascinatie van het duo voor het nieuwe mensbeeld dat zij zien ontstaan. L.A. Raeven: “man en vrouw gaan steeds meer op elkaar lijken en het lichaam wordt steeds vaker gemanipuleerd naar eigen wens. De maakbaarheid van het lichaam lijkt geen grenzen te kennen en wordt steeds meer geaccepteerd. Bij voorbeeld, kleine kinderen krijgen tegenwoordig groeihormonen als ze achter blijven in de groei, dit is een keuze van de ouders die de beslissing nemen over het leven en de carrière van hun kind.”

De titel van de installatie is ontleend aan de Franse filosoof Gilles Deleuze die ‘wild zone’ omschreef als een plaats waar individuen leven die zich buiten de samenleving hebben geplaatst. Zij vormen volgens hem een voorbode van wat er in de toekomst gaat gebeuren in die samenleving. Dit gegeven vormt een belangrijk aspect in het oeuvre van L.A. Raeven; de individuen in de ‘wild zone’ bezitten een bepaalde autonomie die de samenleving beangstigt. Juist de dreiging die de samenleving voelt bij deze ‘wild zone’, en de angst voor mensen die ‘anders’ zijn, wordt in de installaties van het kunstenaarsduo tot uiting gebracht. Wild Zone 3 laat een wereld zien waar kinderen voor altijd kind willen blijven en zelf hun uiterlijk veranderen. “Omdat de adolescentie een cruciale pijnplek in ons leven vormt, vinden wij het uitermate interessant en een enorme uitdaging om met adolescenten het moeilijkste bespreekbaar te maken”, aldus L.A. Raeven.

De titel van de installatie is ontleend aan de Franse filosoof Gilles Deleuze die ‘wild zone’ omschreef als een plaats waar individuen leven die zich buiten de samenleving hebben geplaatst. Zij vormen volgens hem een voorbode van wat er in de toekomst gaat gebeuren in die samenleving. Dit gegeven vormt een belangrijk aspect in het oeuvre van L.A. Raeven; de individuen in de ‘wild zone’ bezitten een bepaalde autonomie die de samenleving beangstigt. Juist de dreiging die de samenleving voelt bij deze ‘wild zone’, en de angst voor mensen die ‘anders’ zijn, wordt in de installaties van het kunstenaarsduo tot uiting gebracht. Wild Zone 3 laat een wereld zien waar kinderen voor altijd kind willen blijven en zelf hun uiterlijk veranderen. “Omdat de adolescentie een cruciale pijnplek in ons leven vormt, vinden wij het uitermate interessant en een enorme uitdaging om met adolescenten het moeilijkste bespreekbaar te maken”, aldus L.A. Raeven.

Museum Arnhem

Museum Arnhem is hét museum voor moderne en hedendaagse kunst én vormgeving van Arnhem. Wij brengen kunst naar mensen toe: vanuit het hart, niet uit het hoofd en zoeken daarbij steeds naar de verbinding. Kunst die gaat over de samenleving en de positie van mensen is wat onze collecties realisme, hedendaagse en niet-westerse kunst, vormgeving en sieraden verbindt. Op onze unieke locatie waar natuur- en cultuurbeleving samenkomen, willen wij in- én uitzicht bieden. Wij doen dat met een gevarieerd en gedurfd programma.

Wild Zone 3 is mogelijk gemaakt dankzij steun van het Mondriaan Fonds.

![]()

Video installatie L.A. Raeven

14 januari 2017 – 5 maart 2017

Museum Arnhem

Utrechtseweg 87

6812 AA Arnhem, Nederland

+31(0)26 30 31 400

Openingstijden

dinsdag t/m zondag 11.00 – 17.00 uur

Op maandag is het museum gesloten.

# Meer informatie via website Museum Arnhem

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Art & Literature News, AUDIO, CINEMA, RADIO & TV, DICTIONARY OF IDEAS, Performing arts

Emile Verhaeren

Autour de ma maison

Pour vivre clair, ferme et juste,

Avec mon coeur, j’admire tout

Ce qui vibre, travaille et bout

Dans la tendresse humaine et sur la terre auguste.

L’hiver s’en va et voici mars et puis avril

Et puis le prime été, joyeux et puéril.

Sur la glycine en fleurs que la rosée humecte,

Rouges, verts, bleus, jaunes, bistres, vermeils,

Les mille insectes

Bougent et butinent dans le soleil.

Oh la merveille de leurs ailes qui brillentEmile Verhaeren

Et leur corps fin comme une aiguille

Et leurs pattes et leurs antennes

Et leur toilette quotidienne

Sur un brin d’herbe ou de roseau !

Sont-ils précis, sont-ils agiles !

Leur corselet d’émail fragile

Est plus changeant que les courants de l’eau;

Grâce à mes yeux qui les reflètent

Je les sens vivre et pénétrer en moi

Un peu ;

Oh leurs émeutes et leurs jeux

Et leurs amours et leurs émois

Et leur bataille, autour des grappes violettes !

Mon coeur les suit dans leur essor vers la clarté,

Brins de splendeur, miettes de beauté,

Parcelles d’or et poussière de vie !

J’écarte d’eux l’embûche inassouvie :

La glu, la boue et la poursuite des oiseaux

Pendant des jours entiers, je défends leurs travaux;

Mon art s’éprend de leurs oeuvres parfaites;

Je contemple les riens dont leur maison est faite

Leur geste utile et net, leur vol chercheur et sûr,

Leur voyage dans la lumière ample et sans voile

Et quand ils sont perdus quelque part, dans l’azur,

Je crois qu’ils sont partis se mêler aux étoiles.

Mais voici l’ombre et le soleil sur le jardin

Et des guêpes vibrant là-bas, dans la lumière;

Voici les longs et clairs et sinueux chemins

Bordés de lourds pavots et de roses trémières;

Aujourd’hui même, à l’heure où l’été blond s’épand

Sur les gazons lustrés et les collines fauves,

Chaque pétale est comme une paupière mauve

Que la clarté pénètre et réchauffe en tremblant.

Les moins fiers des pistils, les plus humbles des feuilles

Sont d’un dessin si pur, si ferme et si nerveux

Qu’en eux

Tout se précipite et tout accueille

L’hommage clair et amoureux des yeux.

L’heure des juillets roux s’est à son tour enfuie,

Et maintenant

Voici le soleil calme avec la douce pluie

Qui, mollement,

Sans lacérer les fleurs admirables, les touchent;

Comme eux, sans les cueillir, approchons-en nos bouches

Et que notre coeur croie, en baisant leur beauté

Faite de tant de joie et de tant de mystère,

Baiser, avec ferveur, délice et volupté,

Les lèvres mêmes de la terre.

Les insectes, les fleurs, les feuilles, les rameaux

Tressent leur vie enveloppante et minuscule

Dans mon village, autour des prés et des closeaux.

Ma petite maison est prise en leurs réseaux.

Souvent, l’après-midi, avant le crépuscule,

De fenêtre en fenêtre, au long du pignon droit,

Ils s’agitent et bruissent jusqu’à mon toit;

Souvent aussi, quand l’astre aux Occidents recule,

J’entends si fort leur fièvre et leur émoi

Que je me sens vivre, avec mon coeur,

Comme au centre de leur ardeur.

Alors les tendres fleurs et les insectes frêles

M’enveloppent comme un million d’ailes

Faites de vent, de pluie et de clarté.

Ma maison semble un nid doucement convoité

Par tout ce qui remue et vit dans la lumière.

J’admire immensément la nature plénière

Depuis l’arbuste nain jusqu’au géant soleil

Un pétale, un pistil, un grain de blé vermeil

Est pris, avec respect, entre mes doigts qui l’aiment;

Je ne distingue plus le monde de moi-même,

Je suis l’ample feuillage et les rameaux flottants,

Je suis le sol dont je foule les cailloux pâles

Et l’herbe des fossés où soudain je m’affale

Ivre et fervent, hagard, heureux et sanglotant.

Emile Verhaeren (1855-1916) poésie

Autour de ma maison

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive U-V, Verhaeren, Emile

Edward Lear

How pleasant to know Mr. Lear

How pleasant to know Mr. Lear,

Who has written such volumes of stuff.

Some think him ill-tempered and queer,

But a few find him pleasant enough.

His mind is concrete and fastidious,

His nose is remarkably big;

His visage is more or less hideous,

His beard it resembles a wig.

He has ears, and two eyes, and ten fingers,

(Leastways if you reckon two thumbs);

He used to be one of the singers,

But now he is one of the dumbs.

He sits in a beautiful parlour,

With hundreds of books on the wall;

He drinks a great deal of marsala,

But never gets tipsy at all.

He has many friends, laymen and clerical,

Old Foss is the name of his cat;

His body is perfectly spherical,

He weareth a runcible hat.

When he walks in waterproof white,

The children run after him so!

Calling out, “He’s gone out in his night-

Gown, that crazy old Englishman, oh!”

He weeps by the side of the ocean,

He weeps on the top of the hill;

He purchases pancakes and lotion,

And chocolate shrimps from the mill.

He reads, but he does not speak, Spanish,

He cannot abide ginger beer;

Ere the days of his pilgrimage vanish,

How pleasant to know Mr. Lear!

Edward Lear (1812 – 1888)

How pleasant to know Mr. Lear

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive K-L, Edward Lear, LIGHT VERSE

Oscar Wilde

To My Wife

I can write no stately proem

As a prelude to my lay;

From a poet to a poem

I would dare to say.

For if of these fallen petals

One to you seem fair,

Love will waft it till it settles

On your hair.

And when wind and winter harden

All the loveless land,

It will whisper of the garden,

You will understand.

And there is nothing left to do

But to kiss once again, and part,

Nay, there is nothing we should rue,

I have my beauty,-you your Art,

Nay, do not start,

One world was not enough for two

Like me and you.

Oscar Wilde (1854 – 1900)

To my wife

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive W-X, Wilde, Oscar, Wilde, Oscar

William Blake

The Tiger

Tiger Tiger. burning bright,

In the forests of the night;

What immortal hand or eye.

Could frame thy fearful symmetry?

In what distant deeps or skies.

Burnt the fire of thine eyes?

On what wings dare he aspire?

What the hand, dare seize the fire?

And what shoulder, & what art,

Could twist the sinews of thy heart?

And when thy heart began to beat.

What dread hand? & what dread feet?

What the hammer? what the chain,

In what furnace was thy brain?

What the anvil? what dread grasp.

Dare its deadly terrors clasp?

When the stars threw down their spears

And watered heaven with their tears:

Did he smile His work to see?

Did he who made the lamb make thee?

Tiger Tiger burning bright,

In the forests of the night:

What immortal hand or eye,

Dare frame thy fearful symmetry?

William Blake (1757 – 1827)

The Tiger

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Blake, William

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature