Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Rainer Maria Rilke

(1875 – 1926)

Départ

Mon amie, il faut que je parte.

Voulez-vous voir

l’endroit sur la carte?

C’est un point noir.

En moi, si la chose

bien me réussit,

ce sera un point rose

dans un vert pays.

Aus: Poèmes et Dédicaces (1920-1926)

Rainer Maria Rilke Gedichte

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive Q-R, Rilke, Rainer Maria

De Kunsthal Rotterdam presenteert het Locomotrutfantje, Moeder de Gans, Spartapiet, Cubaanse vlieg, Doorzager, Blauwwerker en meer beelden van Jules Deelder. Deelder, beter bekend als dichter en nachtburgemeester van Rotterdam, laat de poëzie van zijn verbeelding spreken. Zoals een echte dichter betaamt geeft hij zijn creaties de meest toepasselijke namen. In de tentoonstelling zijn elf unieke ‘Beelder’ te zien, gemaakt van kleurrijk plastic.

Sinds anderhalf jaar verzamelt J.A. Deelder pennen, cocktailstampertjes, injectiespuiten, pijpjes, rietjes, lepeltjes, tandenborstels, speelgoed en lensdopjes, om ze daarna op kleur te sorteren. Met lijm verwerkt Deelder al deze materialen tot driedimensionale objecten, waarmee hij een nieuwe dimensie aan zijn rijke oeuvre van poëzie en performances toevoegt. Hij zegt daar zelf over:

Je zit gewoon een beetje te klootzakke, en op een gegeven moment wordt het wat!

Jules Deelder

Ruimteschepen: Als Deelder’s dochter Ari in 2015 een film maakt over Willem Koopman alias Willem de wielrenner, vindt zij haar vader bereid een aantal ruimteschepen te maken zoals Willem altijd deed in de kroegen van Rotterdam. Koopman, een ex-wielrenner en voormalig zwerver met een bovennatuurlijke missie, zag Rotterdam als een ruimteschip dat elk moment uit het heelal geschoten kon worden. Deelder daarentegen ziet zijn creaties niet opstijgen tot in de verre uithoeken van het heelal, maar juist landen in de Kunsthal.

Over Jules Deelder: J.A. Deelder wordt in 1944 geboren als zoon van een Rotterdamse handelaar in vleeswaren. Sinds de vroege jaren zestig heeft Deelder nationale bekendheid als jazzconnaisseur, schrijver, dichter, performer en bovenal Rotterdammer. Zijn uitgesproken voorkeur voor zwarte kleding, vlinderbrillen, Sparta, Citroën en wielrennen maakt hem tot een graag geziene gast in tv- en radioprogramma’s.

Over Jules Deelder: J.A. Deelder wordt in 1944 geboren als zoon van een Rotterdamse handelaar in vleeswaren. Sinds de vroege jaren zestig heeft Deelder nationale bekendheid als jazzconnaisseur, schrijver, dichter, performer en bovenal Rotterdammer. Zijn uitgesproken voorkeur voor zwarte kleding, vlinderbrillen, Sparta, Citroën en wielrennen maakt hem tot een graag geziene gast in tv- en radioprogramma’s.

De Kunsthal Rotterdam is een van de toonaangevende culturele instellingen in Nederland, gelegen in het Museumpark in Rotterdam. Ontworpen door de beroemde architect Rem Koolhaas in 1992, biedt de Kunsthal zeven verschillende tentoonstellingsruimtes. Jaarlijks presenteert de Kunsthal een gevarieerd programma van circa 25 tentoonstellingen. Omdat er altijd meerdere tentoonstellingen tegelijk te bezichtigen zijn, biedt de Kunsthal een avontuurlijke reis door verschillende werelddelen en kunststromingen. Cultuur voor een breed publiek, van moderne meesters en hedendaagse kunst tot vergeten culturen, fotografie, mode en design. Bij de tentoonstellingen wordt een uitgebreid activiteitenprogramma georganiseerd.

Kunsthal Rotterdam

17 december 2016 tot 19 maart 2017

Dinsdag t/m zaterdag 10 — 17 uur

Zondag 11 — 17 uur

Museumpark

Westzeedijk 341

3015 AA Rotterdam

# Meer informatie op website Kunsthal Rotterdam

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive C-D, Archive C-D, Art & Literature News, AUDIO, CINEMA, RADIO & TV, DICTIONARY OF IDEAS, Exhibition Archive, Jules Deelder

The Curse of Eve

The Curse of Eve

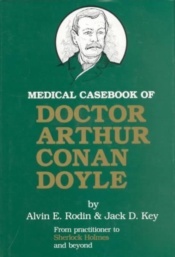

by Arthur Conan Doyle

Robert Johnson was an essentially commonplace man, with no feature to distinguish him from a million others. He was pale of face, ordinary in looks, neutral in opinions, thirty years of age, and a married man. By trade he was a gentleman’s outfitter in the New North Road, and the competition of business squeezed out of him the little character that was left. In his hope of conciliating customers he had become cringing and pliable, until working ever in the same routine from day to day he seemed to have sunk into a soulless machine rather than a man. No great question had ever stirred him. At the end of this snug century, self-contained in his own narrow circle, it seemed impossible that any of the mighty, primitive passions of mankind could ever reach him. Yet birth, and lust, and illness, and death are changeless things, and when one of these harsh facts springs out upon a man at some sudden turn of the path of life, it dashes off for the moment his mask of civilisation and gives a glimpse of the stranger and stronger face below.

Johnson’s wife was a quiet little woman, with brown hair and gentle ways. His affection for her was the one positive trait in his character. Together they would lay out the shop window every Monday morning, the spotless shirts in their green cardboard boxes below, the neckties above hung in rows over the brass rails, the cheap studs glistening from the white cards at either side, while in the background were the rows of cloth caps and the bank of boxes in which the more valuable hats were screened from the sunlight. She kept the books and sent out the bills. No one but she knew the joys and sorrows which crept into his small life. She had shared his exultations when the gentleman who was going to India had bought ten dozen shirts and an incredible number of collars, and she had been as stricken as he when, after the goods had gone, the bill was returned from the hotel address with the intimation that no such person had lodged there. For five years they had worked, building up the business, thrown together all the more closely because their marriage had been a childless one. Now, however, there were signs that a change was at hand, and that speedily. She was unable to come downstairs, and her mother, Mrs. Peyton, came over from Camberwell to nurse her and to welcome her grandchild.

Little qualms of anxiety came over Johnson as his wife’s time approached. However, after all, it was a natural process. Other men’s wives went through it unharmed, and why should not his? He was himself one of a family of fourteen, and yet his mother was alive and hearty. It was quite the exception for anything to go wrong. And yet in spite of his reasonings the remembrance of his wife’s condition was always like a sombre background to all his other thoughts.

Dr. Miles of Bridport Place, the best man in the neighbourhood, was retained five months in advance, and, as time stole on, many little packets of absurdly small white garments with frill work and ribbons began to arrive among the big consignments of male necessities. And then one evening, as Johnson was ticketing the scarfs in the shop, he heard a bustle upstairs, and Mrs. Peyton came running down to say that Lucy was bad and that she thought the doctor ought to be there without delay.

It was not Robert Johnson’s nature to hurry. He was prim and staid and liked to do things in an orderly fashion. It was a quarter of a mile from the corner of the New North Road where his shop stood to the doctor’s house in Bridport Place. There were no cabs in sight so he set off upon foot, leaving the lad to mind the shop. At Bridport Place he was told that the doctor had just gone to Harman Street to attend a man in a fit. Johnson started off for Harman Street, losing a little of his primness as he became more anxious. Two full cabs but no empty ones passed him on the way. At Harman Street he learned that the doctor had gone on to a case of measles, fortunately he had left the address—69 Dunstan Road, at the other side of the Regent’s Canal. Robert’s primness had vanished now as he thought of the women waiting at home, and he began to run as hard as he could down the Kingsland Road. Some way along he sprang into a cab which stood by the curb and drove to Dunstan Road. The doctor had just left, and Robert Johnson felt inclined to sit down upon the steps in despair.

Fortunately he had not sent the cab away, and he was soon back at Bridport Place. Dr. Miles had not returned yet, but they were expecting him every instant. Johnson waited, drumming his fingers on his knees, in a high, dim lit room, the air of which was charged with a faint, sickly smell of ether. The furniture was massive, and the books in the shelves were sombre, and a squat black clock ticked mournfully on the mantelpiece. It told him that it was half-past seven, and that he had been gone an hour and a quarter. Whatever would the women think of him! Every time that a distant door slammed he sprang from his chair in a quiver of eagerness. His ears strained to catch the deep notes of the doctor’s voice. And then, suddenly, with a gush of joy he heard a quick step outside, and the sharp click of the key in the lock. In an instant he was out in the hall, before the doctor’s foot was over the threshold.

“If you please, doctor, I’ve come for you,” he cried; “the wife was taken bad at six o’clock.”

He hardly knew what he expected the doctor to do. Something very energetic, certainly—to seize some drugs, perhaps, and rush excitedly with him through the gaslit streets. Instead of that Dr. Miles threw his umbrella into the rack, jerked off his hat with a somewhat peevish gesture, and pushed Johnson back into the room.

“Let’s see! You DID engage me, didn’t you?” he asked in no very cordial voice.

“Oh, yes, doctor, last November. Johnson the outfitter, you know, in the New North Road.”

“Yes, yes. It’s a bit overdue,” said the doctor, glancing at a list of names in a note-book with a very shiny cover. “Well, how is she?”

“I don’t——”

“Ah, of course, it’s your first. You’ll know more about it next time.”

“Mrs. Peyton said it was time you were there, sir.”

“My dear sir, there can be no very pressing hurry in a first case. We shall have an all-night affair, I fancy. You can’t get an engine to go without coals, Mr. Johnson, and I have had nothing but a light lunch.”

“We could have something cooked for you—something hot and a cup of tea.”

“Thank you, but I fancy my dinner is actually on the table. I can do no good in the earlier stages. Go home and say that I am coming, and I will be round immediately afterwards.”

A sort of horror filled Robert Johnson as he gazed at this man who could think about his dinner at such a moment. He had not imagination enough to realise that the experience which seemed so appallingly important to him, was the merest everyday matter of business to the medical man who could not have lived for a year had he not, amid the rush of work, remembered what was due to his own health. To Johnson he seemed little better than a monster. His thoughts were bitter as he sped back to his shop.

“You’ve taken your time,” said his mother-in-law reproachfully, looking down the stairs as he entered.

“I couldn’t help it!” he gasped. “Is it over?”

“Over! She’s got to be worse, poor dear, before she can be better. Where’s Dr. Miles!”

“He’s coming after he’s had dinner.” The old woman was about to make some reply, when, from the half-opened door behind a high whinnying voice cried out for her. She ran back and closed the door, while Johnson, sick at heart, turned into the shop. There he sent the lad home and busied himself frantically in putting up shutters and turning out boxes. When all was closed and finished he seated himself in the parlour behind the shop. But he could not sit still. He rose incessantly to walk a few paces and then fell back into a chair once more. Suddenly the clatter of china fell upon his ear, and he saw the maid pass the door with a cup on a tray and a smoking teapot.

“Who is that for, Jane?” he asked.

“For the mistress, Mr. Johnson. She says she would fancy it.”

There was immeasurable consolation to him in that homely cup of tea. It wasn’t so very bad after all if his wife could think of such things. So light-hearted was he that he asked for a cup also. He had just finished it when the doctor arrived, with a small black leather bag in his hand.

“Well, how is she?” he asked genially.

“Oh, she’s very much better,” said Johnson, with enthusiasm.

“Dear me, that’s bad!” said the doctor. “Perhaps it will do if I look in on my morning round?”

“No, no,” cried Johnson, clutching at his thick frieze overcoat. “We are so glad that you have come. And, doctor, please come down soon and let me know what you think about it.”

The doctor passed upstairs, his firm, heavy steps resounding through the house. Johnson could hear his boots creaking as he walked about the floor above him, and the sound was a consolation to him. It was crisp and decided, the tread of a man who had plenty of self-confidence. Presently, still straining his ears to catch what was going on, he heard the scraping of a chair as it was drawn along the floor, and a moment later he heard the door fly open and someone come rushing downstairs. Johnson sprang up with his hair bristling, thinking that some dreadful thing had occurred, but it was only his mother-in-law, incoherent with excitement and searching for scissors and some tape. She vanished again and Jane passed up the stairs with a pile of newly aired linen. Then, after an interval of silence, Johnson heard the heavy, creaking tread and the doctor came down into the parlour.

“That’s better,” said he, pausing with his hand upon the door. “You look pale, Mr. Johnson.”

“Oh no, sir, not at all,” he answered deprecatingly, mopping his brow with his handkerchief.

“There is no immediate cause for alarm,” said Dr. Miles. “The case is not all that we could wish it. Still we will hope for the best.”

“Is there danger, sir?” gasped Johnson.

“Well, there is always danger, of course. It is not altogether a favourable case, but still it might be much worse. I have given her a draught. I saw as I passed that they have been doing a little building opposite to you. It’s an improving quarter. The rents go higher and higher. You have a lease of your own little place, eh?”

“Yes, sir, yes!” cried Johnson, whose ears were straining for every sound from above, and who felt none the less that it was very soothing that the doctor should be able to chat so easily at such a time. “That’s to say no, sir, I am a yearly tenant.”

“Ah, I should get a lease if I were you. There’s Marshall, the watchmaker, down the street. I attended his wife twice and saw him through the typhoid when they took up the drains in Prince Street. I assure you his landlord sprung his rent nearly forty a year and he had to pay or clear out.”

“Did his wife get through it, doctor?”

“Oh yes, she did very well. Hullo! hullo!”

He slanted his ear to the ceiling with a questioning face, and then darted swiftly from the room.

It was March and the evenings were chill, so Jane had lit the fire, but the wind drove the smoke downwards and the air was full of its acrid taint. Johnson felt chilled to the bone, though rather by his apprehensions than by the weather. He crouched over the fire with his thin white hands held out to the blaze. At ten o’clock Jane brought in the joint of cold meat and laid his place for supper, but he could not bring himself to touch it. He drank a glass of the beer, however, and felt the better for it. The tension of his nerves seemed to have reacted upon his hearing, and he was able to follow the most trivial things in the room above. Once, when the beer was still heartening him, he nerved himself to creep on tiptoe up the stair and to listen to what was going on. The bedroom door was half an inch open, and through the slit he could catch a glimpse of the clean-shaven face of the doctor, looking wearier and more anxious than before. Then he rushed downstairs like a lunatic, and running to the door he tried to distract his thoughts by watching what; was going on in the street. The shops were all shut, and some rollicking boon companions came shouting along from the public-house. He stayed at the door until the stragglers had thinned down, and then came back to his seat by the fire. In his dim brain he was asking himself questions which had never intruded themselves before. Where was the justice of it? What had his sweet, innocent little wife done that she should be used so? Why was nature so cruel? He was frightened at his own thoughts, and yet wondered that they had never occurred to him before.

As the early morning drew in, Johnson, sick at heart and shivering in every limb, sat with his great coat huddled round him, staring at the grey ashes and waiting hopelessly for some relief. His face was white and clammy, and his nerves had been numbed into a half conscious state by the long monotony of misery. But suddenly all his feelings leapt into keen life again as he heard the bedroom door open and the doctor’s steps upon the stair. Robert Johnson was precise and unemotional in everyday life, but he almost shrieked now as he rushed forward to know if it were over.

One glance at the stern, drawn face which met him showed that it was no pleasant news which had sent the doctor downstairs. His appearance had altered as much as Johnson’s during the last few hours. His hair was on end, his face flushed, his forehead dotted with beads of perspiration. There was a peculiar fierceness in his eye, and about the lines of his mouth, a fighting look as befitted a man who for hours on end had been striving with the hungriest of foes for the most precious of prizes. But there was a sadness too, as though his grim opponent had been overmastering him. He sat down and leaned his head upon his hand like a man who is fagged out.

“I thought it my duty to see you, Mr. Johnson, and to tell you that it is a very nasty case. Your wife’s heart is not strong, and she has some symptoms which I do not like. What I wanted to say is that if you would like to have a second opinion I shall be very glad to meet anyone whom you might suggest.”

Johnson was so dazed by his want of sleep and the evil news that he could hardly grasp the doctor’s meaning. The other, seeing him hesitate, thought that he was considering the expense.

“Smith or Hawley would come for two guineas,” said he. “But I think Pritchard of the City Road is the best man.”

“Oh, yes, bring the best man,” cried Johnson.

“Pritchard would want three guineas. He is a senior man, you see.”

“I’d give him all I have if he would pull her through. Shall I run for him?”

“Yes. Go to my house first and ask for the green baize bag. The assistant will give it to you. Tell him I want the A. C. E. mixture. Her heart is too weak for chloroform. Then go for Pritchard and bring him back with you.”

It was heavenly for Johnson to have something to do and to feel that he was of some use to his wife. He ran swiftly to Bridport Place, his footfalls clattering through the silent streets and the big dark policemen turning their yellow funnels of light on him as he passed. Two tugs at the night-bell brought down a sleepy, half-clad assistant, who handed him a stoppered glass bottle and a cloth bag which contained something which clinked when you moved it. Johnson thrust the bottle into his pocket, seized the green bag, and pressing his hat firmly down ran as hard as he could set foot to ground until he was in the City Road and saw the name of Pritchard engraved in white upon a red ground. He bounded in triumph up the three steps which led to the door, and as he did so there was a crash behind him. His precious bottle was in fragments upon the pavement.

For a moment he felt as if it were his wife’s body that was lying there. But the run had freshened his wits and he saw that the mischief might be repaired. He pulled vigorously at the night-bell.

“Well, what’s the matter?” asked a gruff voice at his elbow. He started back and looked up at the windows, but there was no sign of life. He was approaching the bell again with the intention of pulling it, when a perfect roar burst from the wall.

“I can’t stand shivering here all night,” cried the voice. “Say who you are and what you want or I shut the tube.”

Then for the first time Johnson saw that the end of a speaking-tube hung out of the wall just above the bell. He shouted up it,—

“I want you to come with me to meet Dr. Miles at a confinement at once.”

“How far?” shrieked the irascible voice.

“The New North Road, Hoxton.”

“My consultation fee is three guineas, payable at the time.”

“All right,” shouted Johnson. “You are to bring a bottle of A. C. E. mixture with you.”

“All right! Wait a bit!”

Five minutes later an elderly, hard-faced man, with grizzled hair, flung open the door. As he emerged a voice from somewhere in the shadows cried,—

“Mind you take your cravat, John,” and he impatiently growled something over his shoulder in reply.

The consultant was a man who had been hardened by a life of ceaseless labour, and who had been driven, as so many others have been, by the needs of his own increasing family to set the commercial before the philanthropic side of his profession. Yet beneath his rough crust he was a man with a kindly heart.

“We don’t want to break a record,” said he, pulling up and panting after attempting to keep up with Johnson for five minutes. “I would go quicker if I could, my dear sir, and I quite sympathise with your anxiety, but really I can’t manage it.”

So Johnson, on fire with impatience, had to slow down until they reached the New North Road, when he ran ahead and had the door open for the doctor when he came. He heard the two meet outside the bed-room, and caught scraps of their conversation. “Sorry to knock you up—nasty case—decent people.” Then it sank into a mumble and the door closed behind them.

Johnson sat up in his chair now, listening keenly, for he knew that a crisis must be at hand. He heard the two doctors moving about, and was able to distinguish the step of Pritchard, which had a drag in it, from the clean, crisp sound of the other’s footfall. There was silence for a few minutes and then a curious drunken, mumbling sing-song voice came quavering up, very unlike anything which he had heard hitherto. At the same time a sweetish, insidious scent, imperceptible perhaps to any nerves less strained than his, crept down the stairs and penetrated into the room. The voice dwindled into a mere drone and finally sank away into silence, and Johnson gave a long sigh of relief, for he knew that the drug had done its work and that, come what might, there should be no more pain for the sufferer.

Johnson sat up in his chair now, listening keenly, for he knew that a crisis must be at hand. He heard the two doctors moving about, and was able to distinguish the step of Pritchard, which had a drag in it, from the clean, crisp sound of the other’s footfall. There was silence for a few minutes and then a curious drunken, mumbling sing-song voice came quavering up, very unlike anything which he had heard hitherto. At the same time a sweetish, insidious scent, imperceptible perhaps to any nerves less strained than his, crept down the stairs and penetrated into the room. The voice dwindled into a mere drone and finally sank away into silence, and Johnson gave a long sigh of relief, for he knew that the drug had done its work and that, come what might, there should be no more pain for the sufferer.

But soon the silence became even more trying to him than the cries had been. He had no clue now as to what was going on, and his mind swarmed with horrible possibilities. He rose and went to the bottom of the stairs again. He heard the clink of metal against metal, and the subdued murmur of the doctors’ voices. Then he heard Mrs. Peyton say something, in a tone as of fear or expostulation, and again the doctors murmured together. For twenty minutes he stood there leaning against the wall, listening to the occasional rumbles of talk without being able to catch a word of it. And then of a sudden there rose out of the silence the strangest little piping cry, and Mrs. Peyton screamed out in her delight and the man ran into the parlour and flung himself down upon the horse-hair sofa, drumming his heels on it in his ecstasy.

But often the great cat Fate lets us go only to clutch us again in a fiercer grip. As minute after minute passed and still no sound came from above save those thin, glutinous cries, Johnson cooled from his frenzy of joy, and lay breathless with his ears straining. They were moving slowly about. They were talking in subdued tones. Still minute after minute passing, and no word from the voice for which he listened. His nerves were dulled by his night of trouble, and he waited in limp wretchedness upon his sofa. There he still sat when the doctors came down to him—a bedraggled, miserable figure with his face grimy and his hair unkempt from his long vigil. He rose as they entered, bracing himself against the mantelpiece.

“Is she dead?” he asked.

“Doing well,” answered the doctor.

And at the words that little conventional spirit which had never known until that night the capacity for fierce agony which lay within it, learned for the second time that there were springs of joy also which it had never tapped before. His impulse was to fall upon his knees, but he was shy before the doctors.

“Can I go up?”

“In a few minutes.”

“I’m sure, doctor, I’m very—I’m very——” he grew inarticulate. “Here are your three guineas, Dr. Pritchard. I wish they were three hundred.”

“So do I,” said the senior man, and they laughed as they shook hands.

Johnson opened the shop door for them and heard their talk as they stood for an instant outside.

“Looked nasty at one time.”

“Very glad to have your help.”

“Delighted, I’m sure. Won’t you step round and have a cup of coffee?”

“No, thanks. I’m expecting another case.”

The firm step and the dragging one passed away to the right and the left. Johnson turned from the door still with that turmoil of joy in his heart. He seemed to be making a new start in life. He felt that he was a stronger and a deeper man. Perhaps all this suffering had an object then. It might prove to be a blessing both to his wife and to him. The very thought was one which he would have been incapable of conceiving twelve hours before. He was full of new emotions. If there had been a harrowing there had been a planting too.

“Can I come up?” he cried, and then, without waiting for an answer, he took the steps three at a time.

Mrs. Peyton was standing by a soapy bath with a bundle in her hands. From under the curve of a brown shawl there looked out at him the strangest little red face with crumpled features, moist, loose lips, and eyelids which quivered like a rabbit’s nostrils. The weak neck had let the head topple over, and it rested upon the shoulder.

“Kiss it, Robert!” cried the grandmother. “Kiss your son!”

But he felt a resentment to the little, red, blinking creature. He could not forgive it yet for that long night of misery. He caught sight of a white face in the bed and he ran towards it with such love and pity as his speech could find no words for.

“Thank God it is over! Lucy, dear, it was dreadful!”

“But I’m so happy now. I never was so happy in my life.”

Her eyes were fixed upon the brown bundle.

“You mustn’t talk,” said Mrs. Peyton.

“But don’t leave me,” whispered his wife.

So he sat in silence with his hand in hers. The lamp was burning dim and the first cold light of dawn was breaking through the window. The night had been long and dark but the day was the sweeter and the purer in consequence. London was waking up. The roar began to rise from the street. Lives had come and lives had gone, but the great machine was still working out its dim and tragic destiny.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (1859 – 1930)

Round the Red Lamp: Being Facts and Fancies of Medical Life

The Curse of Eve (#06)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Doyle, Arthur Conan, Doyle, Arthur Conan, DRUGS & DISEASE & MEDICINE & LITERATURE, Round the Red Lamp

Alfred Lord Tennyson

(1809 – 1892)

Beauty

Oh, Beauty, passing beauty! sweetest Sweet!

How canst thou let me waste my youth in sighs;

I only ask to sit beside thy feet.

Thou knowest I dare not look into thine eyes,

Might I but kiss thy hand! I dare not fold

My arms about thee—scarcely dare to speak.

And nothing seems to me so wild and bold,

As with one kiss to touch thy blessèd cheek.

Methinks if I should kiss thee, no control

Within the thrilling brain could keep afloat

The subtle spirit. Even while I spoke,

The bare word KISS hath made my inner soul

To tremble like a lutestring, ere the note

Hath melted in the silence that it broke.

Alfred Lord Tennyson

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Tennyson, Alfred Lord

Emile Verhaeren

Fleur fatale

L’absurdité grandit comme une fleur fatale

Dans le terreau des sens, des coeurs et des cerveaux ;

En vain tonnent, là-bas, les prodiges nouveaux ;

Nous, nous restons croupir dans la raison natale.

Je veux marcher vers la folie et ses soleils,

Ses blancs soleils de lune au grand midi, bizarres,

Et ses échos lointains, mordus de tintamarres

Et d’aboiements et pleins de chiens vermeils.

Iles en fleurs, sur un lac de neige ; nuage

Où nichent des oiseaux sous les plumes du vent ;

Grottes de soir, avec un crapaud d’or devant,

Et qui ne bouge et mange un coin du paysage.

Becs de hérons, énormément ouverts pour rien,

Mouche, dans un rayon, qui s’agite, immobile

L’insconscience douce et le tic-tac débile

De la tranquille mort des fous, je l’entends bien !

Emile Verhaeren (1855-1916) poésie

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive U-V, Verhaeren, Emile

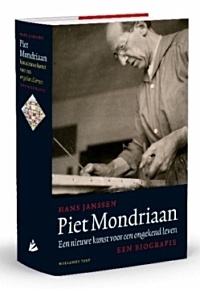

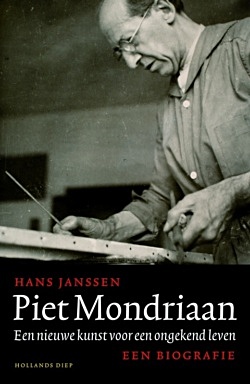

Aan de hand van een nauwgezette reconstructie van werkelijke gebeurtenissen, wordt Mondriaan gevolgd als de man die Nederland ontvluchtte en het moderne leven voluit omarmde, die beschouwend de schilderkunst en het leven liefhad, met alles wat daaraan vastzat, die conservatisme en nazi-terreur trotseerde en die zo de moderniteit waarin wij nu leven verregaand hielp formuleren.

Aan de hand van een nauwgezette reconstructie van werkelijke gebeurtenissen, wordt Mondriaan gevolgd als de man die Nederland ontvluchtte en het moderne leven voluit omarmde, die beschouwend de schilderkunst en het leven liefhad, met alles wat daaraan vastzat, die conservatisme en nazi-terreur trotseerde en die zo de moderniteit waarin wij nu leven verregaand hielp formuleren.

Deze meeslepende biografie werpt nieuw licht op het leven en werk van een van de belangrijkste kunstenaars van de twintigste eeuw. In Piet Mondriaan brengt Hans Janssen de man en de schilder op meesterlijke wijze tot leven. Piet Mondriaan is een bij vlagen ontroerend boek over een kunstenaar die gek was van jazz en boogiewoogie, die open opvattingen had over liefde en huwelijk, vele vrouwen begeerde en liefdesaffaires kende, maar die uiteindelijk maar één echte passie had: het schilderen.

Deze biografie is de vrucht van een diepe fascinatie en bewondering voor het werk van een van onze allerbeste schilders. Janssen beziet deze buitengewone schilder vanuit het werk en niet vanuit onnavolgbare theorieën. Hij plaatst de handeling en de techniek van het schilderen in relatie tot de spirituele, dromerig verhalende betekenissen die in Mondriaans werken schuilgaan, en laat zien hoe die relatie betekenis geeft aan de uitzonderlijke wendingen in het leven en de kunst van deze bijzondere man. In zijn biografie van Piet Mondriaan weet hans Janssen allerlei nieuwe feiten over de schilder boven water te krijgen, onder meer over Mondriaans liefdesleven en een afgeslagen huwelijksaanzoek.

In het boek worden ook twee niet eerder gepubliceerde foto’s van Mondriaan afgedrukt. De foto’s, waarop Mondriaan werkt aan een van zijn bekendste schilderijen: Victory Boogie Woogie, zijn gevonden in de National Galery of Art in Washington, Hans Janssen publiceert ze voor het eerst in zijn boek Piet Mondriaan. Nieuwe kunst voor een ongekend leven, dat op 13 augustus ten doop gehouden werd in het Gemeentemuseum in Den Haag.

In het boek worden ook twee niet eerder gepubliceerde foto’s van Mondriaan afgedrukt. De foto’s, waarop Mondriaan werkt aan een van zijn bekendste schilderijen: Victory Boogie Woogie, zijn gevonden in de National Galery of Art in Washington, Hans Janssen publiceert ze voor het eerst in zijn boek Piet Mondriaan. Nieuwe kunst voor een ongekend leven, dat op 13 augustus ten doop gehouden werd in het Gemeentemuseum in Den Haag.

Janssen belicht ook het liefdesleven van Mondriaan. ‘Mondriaan wordt vaak geportretteerd als een rationele, ascetische man. Een monnik die zich opsloot in zijn atelier. Maar wie de historische feiten op een rij zet, komt op het tegendeel uit,’ stelt Janssen. ‘Mondriaan besloot Lily Bles, de dochter van dichter Dop Bles, in 1931 een huwelijksaanzoek te doen, per brief. De kunstenaar kocht zelfs een groter bed, huurde een zolderkamertje boven zijn eigen keukentje, timmerde een wiegje en schilderde zijn hele atelier.’

Hans Janssen

Piet Mondriaan: een nieuwe kunst voor een ongekend leven

De eerste volwaardige biografie van leven en werk van Piet Mondriaan

Gebonden, 608 p.

Uitg. Hollands Diep

ISBN: 9789048833580

€ 39.99 – 2016

‘Janssen staat bekend als dé Mondriaandeskundige en heeft al diverse boeken aan de kunstenaar gewijd. In de biografie kiest hij voor een nieuwe benadering: hij probeert onder de huid van de kunstenaar te kruipen en de schilder als ‘mens’ weer te geven. Hij kijkt met de ogen van Mondriaan naar een schilderij. Zo leest het boek hier en daar als een “vie romancée”, alsof de schrijver – en dus ook de lezer – bij Mondriaan in zijn atelier staat.’ PZC

# Meer informatie op website Hollands Diep

fleursdumal.nl magazine for art & literature

More in: - Book News, Antony Kok, Art & Literature News, De Stijl, Doesburg, Theo van, Essays about Van Doesburg, Kok, Mondriaan, Schwitters, Milius & Van Moorsel, Kok, Antony, Magazines, Modernisme, Piet Mondriaan, Piet Mondriaan, Theo van Doesburg, Theo van Doesburg, Theo van Doesburg (I.K. Bonset)

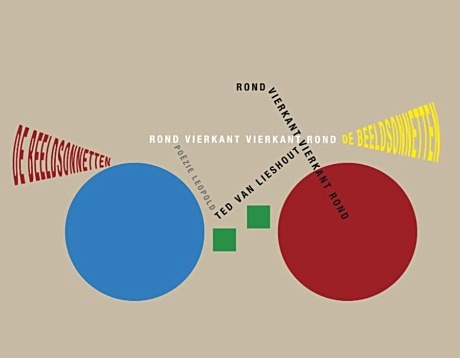

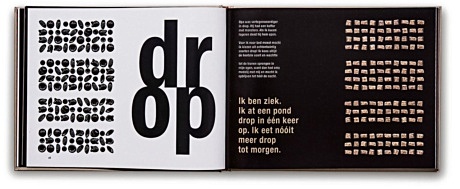

Poëzie is spelen met taal. Maar soms is het maken van een gedicht een lastig spel. Een sonnet, bijvoorbeeld, moet voldoen aan veel regels. Kan dat niet makkelijker? Ja. Want als het niet gaat in letters, dan lukt het wel in beeld!

In dit boek staan naast ‘gewone’ gedichten bijna alle beeldsonnetten die Ted van Lieshout in tien jaar tijd maakte. Maar ook vind je er werk in van kinderen en volwassenen die zich door het beeldsonnet lieten inspireren. En als je tóch een gedicht van taal wilt maken, dan zit je goed met dit boek, want het staat boordevol informatie en tips.

In 2005 verscheen het eerste beeldsonnet van Ted van Lieshout. Na tien jaar bekroont hij het maken van beeldsonnetten met een boek dat niet alleen alle beeldsonnetten bevat, maar ook een keur aan gedichten van taal, aangevuld met geestige informatie over poëzie en hoe je zelf gedichten kunt maken: Rond vierkant vierkant rond.

‘Gedichten, zo mooi dat je ze graag levensgroot aan je muur zou hangen.’ – NRC

Ted van Lieshout: ‘Poëzie is spelen met taal. Maar soms is het maken van een gedicht een lastig spel. Een sonnet, bijvoorbeeld, moet voldoen aan veel regels. Kan dat niet makkelijker? Ja. Want als het niet gaat in letters, dan lukt het wel in beeld!’

De ochtend is nog grauw van mist en kou.

Mijn fiets staat stil te slapen in de schuur.

Ik moet naar school, ik trek hem aan het stuur

naar buiten. ‘Ik ben al laat,’ zeg ik, ‘kom nou!’

Ted van Lieshout

Rond vierkant vierkant rond

De beeldsonnetten

Pagina’s 112

ISBN 978-90-258-6873-4

Leopold – Prijs € 19,99

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: *Concrete + Visual Poetry K-O, - Book News, Archive K-L, Art & Literature News, Children's Poetry, Lieshout, Ted van, Ted van Lieshout

Thomas Traherne

(1637 – 1674)

Walking

To walk abroad is, not with eyes,

But thoughts, the fields to see and prize;

Else may the silent feet,

Like logs of wood,

Move up and down, and see no good

Nor joy nor glory meet.

Ev’n carts and wheels their place do change,

But cannot see, though very strange

The glory that is by;

Dead puppets may

Move in the bright and glorious day,

Yet not behold the sky.

And are not men than they more blind,

Who having eyes yet never find

The bliss in which they move;

Like statues dead

They up and down are carried

Yet never see nor love.

To walk is by a thought to go;

To move in spirit to and fro;

To mind the good we see;

To taste the sweet;

Observing all the things we meet

How choice and rich they be.

To note the beauty of the day,

And golden fields of corn survey;

Admire each pretty flow’r

With its sweet smell;

To praise their Maker, and to tell

The marks of his great pow’r.

To fly abroad like active bees,

Among the hedges and the trees,

To cull the dew that lies

On ev’ry blade,

From ev’ry blossom; till we lade

Our minds, as they their thighs.

Observe those rich and glorious things,

The rivers, meadows, woods, and springs,

The fructifying sun;

To note from far

The rising of each twinkling star

For us his race to run.

A little child these well perceives,

Who, tumbling in green grass and leaves,

May rich as kings be thought,

But there’s a sight

Which perfect manhood may delight,

To which we shall be brought.

While in those pleasant paths we talk,

‘Tis that tow’rds which at last we walk;

For we may by degrees

Wisely proceed

Pleasures of love and praise to heed,

From viewing herbs and trees.

Thomas Traherne

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, CLASSIC POETRY

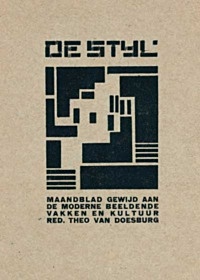

Tentoonstelling De Stijl in het Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam

Tentoonstelling De Stijl in het Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam

3 dec 2016 – 21 mei 2017

Wat heeft het werk van Isa Genzken met De Stijl te maken? En hoe verhoudt Bas Jan Ader zich tot De Stijl, of de iconische Lichtenstein uit de collectie van het Stedelijk? In De Stijl in het Stedelijk is in zes zalen te zien hoe De Stijl in de collectie vertegenwoordigd is, en hoe de stroming weerklank vond en vindt bij andere kunstenaars in de collectie. Onderdeel van het 100 jaar De Stijl programma.

De presentatie is opgebouwd rond verschillende facetten, zoals kleurgebruik, de diagonaal, zuiverheid, architectuur en de verspreiding van de stijl. Werken van De Stijl die de ideologie bij uitstek tot uitdrukking brengen, worden gecombineerd met werk van naoorlogse kunstenaars. Het is duidelijk dat De Stijl een onontkoombaar gegeven was voor de generaties die volgden. Sommige kunstenaars brengen een geïnspireerde ode, anderen onderzoeken de hedendaagse betekenis ervan. De dominantie van De Stijl riep ook parodiërende reacties op, zoals de Infe©ted Mondrian, de zieke Mondriaan, van General Idea uit de jaren 90.

De Stijl en het Stedelijk

In oktober 1917 verscheen de eerste aflevering van De Stijl, maandblad voor de moderne beeldende vakken, waarin kunstenaars, vormgevers en architecten vernieuwende ideeën publiceerden over een radicale hervorming van de kunst, die moest leiden naar een wereld van totale harmonie en een eenheid van kunst en leven. Hun theorieën over kleur en ruimte leidden tot een revolutionaire, volledig abstracte beeldtaal die aan die harmonie uitdrukking moest geven.

Het Stedelijk Museum legde een grote verzameling aan van De Stijl en leverde mede dankzij een aantal belangrijke tentoonstellingen een bijdrage aan de internationale waardering voor de beweging, in het bijzonder met het grote overzicht in 1951, georganiseerd door toenmalig directeur Willem Sandberg, dat doorreisde naar het MoMA in New York.

De Stijl werd in 1931 opgeheven, maar is tot op de dag van vandaag voor kunstenaars, vormgevers en architecten een inspiratiebron, of juist een onontkoombaar gegeven om zich tegen af te zetten.

2017: 100 jaar de stijl

In 2017 is het 100 jaar geleden dat De Stijl werd opgericht, de legendarische kunstenaars- en architectengroep rond Theo van Doesburg, Piet Mondriaan en Gerrit Rietveld. Dat wordt in Nederland door verschillende musea groot gevierd. Het Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam was de katalysator van de internationale doorbraak van De Stijl en beschikt over een van de grootste collecties van de beweging. In 2017 wijdt het Stedelijk een jaarlang presentaties aan onverwachte kanten van De Stijl, zoals een tentoonstelling over Chris Beekman, het afvallige lid van De Stijl. Ook legt het museum een verbinding met de Russische Revolutie, die eveneens in 1917 plaatsvond.

De tentoonstellingen omtrent 100 Jaar De Stijl zijn onderdeel van een nieuw, langlopend onderzoeksprogramma van het Stedelijk. Daarin wordt de collectie van het museum, zonder onderscheid tussen beeldende kunst en vormgeving, op een experimentele manier benaderd, geïnterpreteerd en gepresenteerd. Ook de rijke geschiedenis van het instituut en de archieven worden daarbij betrokken.

100 JAAR DE STIJL

Stedelijk Museum belicht een jaar lang onverwachte kanten van De Stijl:

De Stijl in het Stedelijk

De Stijl in het Stedelijk

3 december 2016 – 21 mei 2017

Het Stedelijk laat in zes zalen zien hoe De Stijl in de collectie vertegenwoordigd is, en hoe de stroming weerklank vond en vindt bij andere kunstenaars in de collectie. Wat heeft bijvoorbeeld het werk van Isa Genzken met De Stijl te maken? En hoe verhoudt Bas Jan Ader zich tot De Stijl, of de iconische Lichtenstein uit de collectie van het Stedelijk? De presentatie is opgebouwd rond verschillende facetten, zoals kleurgebruik, de diagonaal, zuiverheid, architectuur en de verspreiding van De Stijl. Werken van De Stijl die de ideologie bij uitstek tot uitdrukking brengen, worden gecombineerd met werk van naoorlogse kunstenaars. Het is duidelijk dat De Stijl een onontkoombaar gegeven was voor de generaties die volgden. Sommige kunstenaars brengen een geïnspireerde ode, anderen onderzoeken de hedendaagse betekenis ervan. De dominantie van De Stijl riep ook parodiërende reacties op, zoals de Infe©ted Mondrian, de zieke Mondriaan, van General Idea uit de jaren 90.

Chris Beekman, de afvallige van De Stijl

8 april – 17 september 2017

Het Stedelijk besteedt aandacht aan het werk van Chris Beekman, een van de meest politiek actieve kunstenaars verbonden aan deze beweging. Voor het eerst is het oeuvre van deze vergeten Stijl-kunstenaar te zien, in een tentoonstelling met circa 80 werken, uit de collecties van het Stedelijk Museum, Museum Kröller Müller en het Amsterdam Museum.

Schilder en communist Chris Beekman (1887-1964) was bevriend met links-radicalen als Bart van der Leck, Peter Alma en Robert van ’t Hoff. Zijn werken uit de beginjaren van De Stijl laten een grote vrijheid zien in geometrische vorm en kleur. Beekman kreeg echter een afkeer van de louter ideële discussie binnen de stroming en het, in zijn ogen, gebrek aan concrete maatschappelijke betekenisgeving van De Stijl. De wereld stond in brand en daar moest begrijpelijke schilderkunst voor gemaakt worden. Hij brak begin jaren 20 dan ook met de abstractie om zich te wijden aan figuratieve kunst met een sociale inslag. In de tentoonstelling is de breuk met De Stijl goed te volgen: waar Mondriaan zijn meest efemere zwart-wit werken schildert, zoekt Beekman gedesillusioneerd een weg terug naar het volk. Hiermee vormt hij een trait-d’union tussen De Stijl en de Russische Revolutie: ook daar keerde menig kunstenaar, waaronder Malevich, terug naar de figuratie.

De tentoonstelling brengt, naast zijn werk van direct voor, tijdens en na de De Stijl-periode, ook de directe context waarin Beekman werkte in beeld. Zo zijn er banden met onder meer Bart van der Leck en Piet Mondriaan, met wie hij in Laren bevriend raakte, en is ook werk te zien van Jacob Bendien, Johan van Hell en Ferdinand Erfmann, en vroeg, verrassend abstract werk van Carel Willink.

Vanaf eind mei 2017 wordt er een epiloog aan de tentoonstelling toegevoegd, waarin duidelijk wordt dat Beekman nummers van De Stijl, met foto’s van abstract werk en De Stijl architectuur, opstuurde naar Malevich. Onderzoek suggereert dat een trapontwerp van Van ’t Hoff wellicht van invloed is geweest op de ontwikkeling van de laatste fase van Malevich’ suprematisme: de Architektons.

Vanaf eind mei 2017 wordt er een epiloog aan de tentoonstelling toegevoegd, waarin duidelijk wordt dat Beekman nummers van De Stijl, met foto’s van abstract werk en De Stijl architectuur, opstuurde naar Malevich. Onderzoek suggereert dat een trapontwerp van Van ’t Hoff wellicht van invloed is geweest op de ontwikkeling van de laatste fase van Malevich’ suprematisme: de Architektons.

Op 2 en 3 juni 2017 houden het Stedelijk Museum en de Khardzhiev Stichting een internationaal symposium: The Many Lives of the Russian Avant-garde – Symposium in honour of Nikolai Khardzhiev, scholar and collector (1903-1996). Met deelname van vooraanstaande wetenschappers en met aandacht voor de Russische avant-garde als multidisciplinaire onderneming: kunstzinnig, literair, politiek en filosofisch.

De Stijl en Metz & Co

14 oktober 2017– 28 januari 2018

Leden van De Stijl ontwierpen onder meer meubelen, interieurtextiel en verpakkingen voor het Amsterdamse warenhuis Metz & Co. Het warenhuis speelde vanaf eind jaren 20 een grote rol bij de verspreiding van het modernisme in Nederland. Een aantal opvallende werken uit de collectie van het Stedelijk, van onder anderen Bart van der Leck, Friedrich Vordemberge-Gildewart en Vilmos Huszár, worden gepresenteerd in samenhang met hun toegepaste werk voor Metz & Co. De Zigzag-meubelontwerpen van Gerrit Rietveld – waarvan enkele vanaf 1934 bij Metz & Co in productie werden genomen – krijgen bijzondere aandacht. Daarnaast wordt werk getoond van ontwerpers die door De Stijl beïnvloed werden, zoals Sonia Delaunay, die veel stoffen voor het warenhuis ontwierp.

In 2017 zal het Stedelijk ook aandacht besteden aan de Russische revolutie, die honderd jaar geleden plaatsvond, met onder meer een presentatie over de Russische revolutie en film(affiches), en reflecties van kunstenaars uit de jaren 80 en 90 op de Sovjetmaatschappij.

De tentoonstellingen omtrent 100 Jaar De Stijl zijn onderdeel van een nieuw, langlopend onderzoeksprogramma van het Stedelijk. Daarin wordt de collectie van het museum, zonder onderscheid tussen beeldende kunst en vormgeving, op een experimentele manier benaderd, geïnterpreteerd en gepresenteerd. Ook de rijke geschiedenis van het instituut en de archieven worden daarbij betrokken.

Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam

Museumplein 10

1071 DJ Amsterdam

# Meer informatie op website SM

# Meer informatie over De Stijl op website Antony Kok

fleursdumal.nl magazine for art & literature

More in: Antony Kok, Antony Kok, Art & Literature News, Bauhaus, Dadaïsme, De Stijl, Design, DICTIONARY OF IDEAS, Doesburg, Theo van, Essays about Van Doesburg, Kok, Mondriaan, Schwitters, Milius & Van Moorsel, Evert en Thijs Rinsema, FDM Art Gallery, Futurisme, Kok, Antony, Kurt Schwitters, Magazines, Piet Mondriaan, Theo van Doesburg, Theo van Doesburg, Theo van Doesburg (I.K. Bonset)

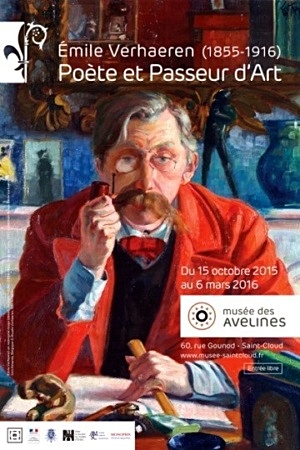

Verhaeren verbeeld

De schrijver-criticus Emile Verhaeren en de kunst van zijn tijd

Nog te zien t/m 15.01.2017 in M.S.K. in Gent

In samenwerking met het Verhaerenmuseum in Sint-Amands aan de Schelde en de Université Libre de Bruxelles organiseert het Museum voor Schone Kunsten Gent een grote tentoonstelling over de uit Gent afkomstige dichter en kunstcriticus Emile Verhaeren, die 100 jaar geleden overleed.

De tentoonstelling belicht het universele karakter van Verhaerens oeuvre, zijn netwerk binnen de kunstwereld rond de eeuwwisseling en de internationale aandacht voor zijn werk, in eerste instantie in België en Frankrijk, maar ook in Rusland en andere landen.

Emile Verhaeren volgde tussen 1880 en 1916 volgde hij nauwgezet de ontwikkeling van de Belgische avant-garde-kunst. Hij verdedigde het naturalisme en de sociale kunst, het impressionisme en het neo-impressionisme, het symbolisme. Bovenal was hij een verdediger van de moderniteit die hij in de kunst van zijn tijd terugvond.

Emile Verhaeren volgde tussen 1880 en 1916 volgde hij nauwgezet de ontwikkeling van de Belgische avant-garde-kunst. Hij verdedigde het naturalisme en de sociale kunst, het impressionisme en het neo-impressionisme, het symbolisme. Bovenal was hij een verdediger van de moderniteit die hij in de kunst van zijn tijd terugvond.

In zijn poëzie en geschriften bundelt Verhaeren zijn gevoelens, passies en artistieke strijdpunten. Meer dan 100 jaar later laten ze ons toe het werk van nationale en internationale kunstenaars te herontdekken door de ogen van een eigenzinnig kenner.

De tentoonstelling brengt de historische en artistieke context tot leven waarin het oeuvre van de dichter-criticus tot stand kwam. Het MSK laat o.a. de rijke collectie schilderijen, beeldhouwwerken en werken op papier zien. Zoals publiekslievelingen als ‘De Lezing van Emile Verhaeren’ door Théo Van Rysselberghe of ‘Kinderen aan het ochtendtoilet’ van James Ensor in dialoog met collectiestukken die de reserves weinig verlaten.

Tegelijk haalt het MSK een grote reeks kunstwerken uit internationale publieke en private verzamelingen naar Gent, met stukken van ondermeer Auguste Rodin, Paul Signac, Maximilien Luce of Odilon Redon. Ook kunstenaars als Léon Frédéric, Eugène Laermans en Constantin Meunier, Jan Toorop en Guillaume Vogels, Henry Van de Velde, Fernand Khnopff en George Minne kunnen uiteraard niet ontbreken. In totaal brengt het MSK niet minder dan 200 werken uit het fin de siècle op zaal.

Verhaeren verbeeld

De schrijver-criticus Emile Verhaeren en de kunst van zijn tijd (1881-1916)

Nog te zien t/m 15.01.2017 in M.S.K. in Gent

Museum voor Schone Kunst Gent

Fernand Scribedreef 1

Citadelpark

9000 Gent

# Meer informatie op website MSK Gent

fleursdumal.nl magazine for art & literature

More in: Archive U-V, Art & Literature News, Art Criticism, Exhibition Archive, Historia Belgica, Verhaeren, Emile

Winternachten Festival: rake woorden, diepzinnige waarnemingen en richtinggevende verbeelding

Van donderdag 19 tot en met zondag 22 januari 2017 brengt Winternachten schrijvers, journalisten, denkers, dichters en publiek samen in Theater aan het Spui en Filmhuis Den Haag. De 22e editie van het mooiste literatuurfestival van Nederland heeft als motto ‘Is this the real life?’ over wat er is maar verborgen blijft, en over fake – dat wat er niet is maar ons wordt voorgehouden.

Tijdens de grote festivalavonden Friday & Saturday Night Unlimited keert dit motto terug in debatten als This is Not America, IS: The Horror Show, Fictie in tijden van Fake en De verborgen stad.

Onder de tachtig gasten zijn topauteurs als Arnon Grunberg, Tommy Wieringa, Bas Heijne, Joke Hermsen en, uit het buitenland, Ian Buruma, Colson Whitehead, Michel Faber, Tomás Sedláček, Michaïl Sjisjkin en Salena Godden.

Op vrijdag- en zaterdagavond verzorgt Spoken Beat Night optredens waarin jazz, spoken word, wereldmuziek, voordracht, live animatie en funky beats zich vermengen. Tijdens het festival worden de Oxfam Novib PEN Awards (donderdag 19 januari) en de Jan Campert-prijzen (zondag 22 januari) uitgereikt.

Winternachten is een vierdaags festival dat inspireert met andere verhalen, nieuwe invalshoeken en actuele thema’s. Internationale en Nederlandstalige schrijvers reflecteren in zaalgesprekken en debatten, rond filmvertoningen en muziekoptredens aan de hand van het motto ‘Is this the real life?’ op de grote en de alledaagse vragen waar Nederland en Europa mee worstelen.

Winternachten is er voor iedereen die stof tot nadenken zoekt, die romans, poëzie of non-fictie leest, die een ander perspectief op de actualiteit wil, die graag luistert naar of deelneemt aan het vertellen van verhalen van ver of dichtbij, die wil ontmoeten en kennismaken.

Reading the Bible with Sedlacek – World Storytelling in het Institute of Social Studies – Door het Noordeinde: verhalen van achter de façades – Wereldverhalen in Theater Dakota – NRC Leesclub Live: Louise O. Fresco – Saturday Night Unlimited – VPRO O.V.T. Live – Schrijversfeest

Arjan Peters – Arnon Grunberg – Baban Kirkuki – Balout Khazraei – Bas Heijne – Beri Shalmashi – Carolina Trujillo – Christine Otten – Colson Whitehead – Corina Duijndam – DJ Socrates – Damiaan Denys – Delphine Lecompte – Dieter van der Westen– Dominique De Groen – Dorit Rabinyan – Felix Rottenberg – Francis Broekhuijsen – Frank Westerman – Gerlinda Heywegen – Hanna Bervoets – Hannah van Binsbergen – Hassan Blasim – Hassnae Bouazza – Ian Buruma – Ilja Leonard Pfeijffer – Jeroen van Kan – Joke Hermsen – Lex Bohlmeijer – Maarten van der Graaff – Margriet Oostveen – Maria Vlaar – Marieke Rijneveld – Mehdi Arami – Michalis Cholevas – Michaïl Sjisjkin – Michel Faber – Mira Feticu – Mircea Cărtărescu – Obe Alkema – Ofran Badakhshani – Olga Grjasnowa – Omar Munie – Piotr Ibrahim Kalwas – Rodaan Al Galidi – Rodrigo Hasbún – Roos Laan – Salena Godden – Sana Valiulina – Simone Atangana Bekono – Simone van Saarloos – Spoken Beat Night – Stephan Sanders – Stine Jensen – Tom Dommisse – Tomas Sedlacek – Tommy Wieringa – Ton van ‘t Hof

Arjan Peters – Arnon Grunberg – Baban Kirkuki – Balout Khazraei – Bas Heijne – Beri Shalmashi – Carolina Trujillo – Christine Otten – Colson Whitehead – Corina Duijndam – DJ Socrates – Damiaan Denys – Delphine Lecompte – Dieter van der Westen– Dominique De Groen – Dorit Rabinyan – Felix Rottenberg – Francis Broekhuijsen – Frank Westerman – Gerlinda Heywegen – Hanna Bervoets – Hannah van Binsbergen – Hassan Blasim – Hassnae Bouazza – Ian Buruma – Ilja Leonard Pfeijffer – Jeroen van Kan – Joke Hermsen – Lex Bohlmeijer – Maarten van der Graaff – Margriet Oostveen – Maria Vlaar – Marieke Rijneveld – Mehdi Arami – Michalis Cholevas – Michaïl Sjisjkin – Michel Faber – Mira Feticu – Mircea Cărtărescu – Obe Alkema – Ofran Badakhshani – Olga Grjasnowa – Omar Munie – Piotr Ibrahim Kalwas – Rodaan Al Galidi – Rodrigo Hasbún – Roos Laan – Salena Godden – Sana Valiulina – Simone Atangana Bekono – Simone van Saarloos – Spoken Beat Night – Stephan Sanders – Stine Jensen – Tom Dommisse – Tomas Sedlacek – Tommy Wieringa – Ton van ‘t Hof

Writers Unlimited Winternachten Festival Den Haag – 19 t/m 22 januari 2017

# Meer informatie op website Winternachten

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book Lovers, Arnon Grunberg, Art & Literature News, Bas Heijne, Lecompte, Delphine, Rijneveld, Marieke Lucas, Winternachten, Wintertuin Festival

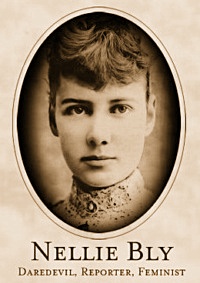

Ten Days in a Mad-House

Ten Days in a Mad-House

(Chapter IV: Judge Duffy and the Police)

by Nellie Bly

But to return to my story. I kept up my role until the assistant matron, Mrs. Stanard, came in. She tried to persuade me to be calm. I began to see clearly that she wanted to get me out of the house at all hazards, quietly if possible. This I did not want. I refused to move, but kept up ever the refrain of my lost trunks. Finally some one suggested that an officer be sent for. After awhile Mrs. Stanard put on her bonnet and went out. Then I knew that I was making an advance toward the home of the insane. Soon she returned, bringing with her two policemen–big, strong men–who entered the room rather unceremoniously, evidently expecting to meet with a person violently crazy. The name of one of them was Tom Bockert.

When they entered I pretended not to see them. “I want you to take her quietly,” said Mrs. Stanard. “If she don’t come along quietly,” responded one of the men, “I will drag her through the streets.” I still took no notice of them, but certainly wished to avoid raising a scandal outside. Fortunately Mrs. Caine came to my rescue. She told the officers about my outcries for my lost trunks, and together they made up a plan to get me to go along with them quietly by telling me they would go with me to look for my lost effects. They asked me if I would go. I said I was afraid to go alone. Mrs. Stanard then said she would accompany me, and she arranged that the two policemen should follow us at a respectful

distance. She tied on my veil for me, and we left the house by the basement and started across town, the two officers following at some distance behind. We walked along very quietly and finally came to the station house, which the good woman assured me was the express office, and that there we should certainly find my missing effects. I went inside with fear and trembling, for good reason.

A few days previous to this I had met Captain McCullagh at a meeting held in Cooper Union. At that time I had asked him for some information which he had given me. If he were in, would he not recognize me? And then all would be lost so far as getting to the island was concerned. I pulled my sailor hat as low down over my face as I possibly could, and prepared for the ordeal. Sure enough there was sturdy Captain McCullagh standing near the desk.

He watched me closely as the officer at the desk conversed in a low tone with Mrs. Stanard and the policeman who brought me.

“Are you Nellie Brown?” asked the officer. I said I supposed I was. “Where do you come from?” he asked. I told him I did not know, and then Mrs. Stanard gave him a lot of information about me–told him how strangely I had acted at her home; how I had not slept a wink all night, and that in her opinion I was a poor unfortunate who had been driven crazy by inhuman treatment. There was some discussion between Mrs. Standard and the two officers, and Tom Bockert was told to take us down to the court in a car.

In the hands of the police.

“Come along,” Bockert said, “I will find your trunk for you.” We all went together, Mrs. Stanard, Tom Bockert, and myself. I said it was very kind of them to go with me, and I should not soon forget them. As we walked along I kept up my refrain about my trucks, injecting occasionally some remark about the dirty condition of the streets and the curious character of the people we met on the way. “I don’t think I have ever seen such people before,” I said. “Who are they?” I asked, and my companions looked upon me with expressions of pity, evidently believing I was a foreigner, an emigrant or something of the sort. They told me that the people around me were working people. I remarked once more that I thought there were too many working people in the world for the amount of work to be done, at which remark Policeman P. T. Bockert eyed me closely, evidently thinking that my mind was gone for good. We passed several other policemen, who generally asked my sturdy guardians what was the matter with me. By this time quite a number of ragged children were following us too, and they passed remarks about me that were to me original as well as amusing.

“What’s she up for?” “Say, kop, where did ye get her?” “Where did yer pull ‘er?”

“She’s a daisy!”

Poor Mrs. Stanard was more frightened than I was. The whole situation grew interesting, but I still had fears for my fate before the judge.

At last we came to a low building, and Tom Bockert kindly volunteered the information: “Here’s the express office. We shall soon find those trunks of yours.”

The entrance to the building was surrounded by a curious crowd and I did not think my case was bad enough to permit me passing them without some remark, so I asked if all those people had lost their trunks.

“Yes,” he said, “nearly all these people are looking for trunks.”

I said, “They all seem to be foreigners, too.” “Yes,” said Tom, “they are all foreigners just landed. They have all lost their trunks, and it takes most of our time to help find them for them.”

We entered the courtroom. It was the Essex Market Police Courtroom. At last the question of my sanity or insanity was to be decided. Judge Duffy sat behind the high desk, wearing a look which seemed to indicate that he was dealing out the milk of human kindness by wholesale. I rather feared I would not get the fate I sought, because of the kindness I saw on every line of his face, and it was with rather a sinking heart that I followed Mrs. Stanard as she answered the summons to go up to the desk, where Tom Bockert had just given an account of the affair.

“Come here,” said an officer. “What is your name?”

“Nellie Brown,” I replied, with a little accent. “I have lost my trunks, and would like if you could find them.”

“When did you come to New York?” he asked.

“I did not come to New York,” I replied (while I added, mentally, “because I have been here for some time.”)

“But you are in New York now,” said the man.

“No,” I said, looking as incredulous as I thought a crazy person could, “I did not come to New York.”

“That girl is from the west,” he said, in a tone that made me tremble. “She has a western accent.”

Some one else who had been listening to the brief dialogue here asserted that he had lived south and that my accent was southern, while another officer was positive it was eastern. I felt much relieved when the first spokesman turned to the judge and said:

“Judge, here is a peculiar case of a young woman who doesn’t know who she is or where she came from. You had better attend to it at once.”

I commenced to shake with more than the cold, and I looked around at the strange crowd about me, composed of poorly dressed men and women with stories printed on their faces of hard lives, abuse and poverty. Some were consulting eagerly with friends, while others sat still with a look of utter hopelessness. Everywhere was a sprinkling of well-dressed, well-fed officers watching the scene passively and almost indifferently. It was only an old story with them. One more unfortunate added to a long list which had long since ceased to be of any interest or concern to them.

Nellie before Judge Duffy.

“Come here, girl, and lift your veil,” called out Judge Duffy, in tones which surprised me by a harshness which I did not think from the kindly face he possessed.

“Who are you speaking to?” I inquired, in my stateliest manner.

“Come here, my dear, and lift your veil. You know the Queen of England, if she were here, would have to lift her veil,” he said, very kindly.

“That is much better,” I replied. “I am not the Queen of England, but I’ll lift my veil.”

As I did so the little judge looked at me, and then, in a very kind and gentle tone, he said:

“My dear child, what is wrong?”

“Nothing is wrong except that I have lost my trunks, and this man,” indicating Policeman Bockert, “promised to bring me where they could be found.”

“What do you know about this child?” asked the judge, sternly, of Mrs. Stanard, who stood, pale and trembling, by my side.

“I know nothing of her except that she came to the home yesterday and asked to remain overnight.”

“The home! What do you mean by the home?” asked Judge Duffy, quickly.

“It is a temporary home kept for working women at No. 84 Second Avenue.”

“What is your position there?”

“I am assistant matron.”

“Well, tell us all you know of the case.”

“When I was going into the home yesterday I noticed her coming down the avenue. She was all alone. I had just got into the house when the bell rang and she came in. When I talked with her she wanted to know if she could stay all night, and I said she could. After awhile she said all the people in the house looked crazy, and she was afraid of them. Then she would not go to bed, but sat up all the night.”

“Had she any money?”

“Yes,” I replied, answering for her, “I paid her for everything, and the eating was the worst I ever tried.”

There was a general smile at this, and some murmurs of “She’s not so crazy on the food question.”

“Poor child,” said Judge Duffy, “she is well dressed, and a lady. Her English is perfect, and I would stake everything on her being a good girl. I am positive she is somebody’s darling.”

At this announcement everybody laughed, and I put my handkerchief over my face and endeavored to choke the laughter that threatened to spoil my plans, in despite of my resolutions.

“I mean she is some woman’s darling,” hastily amended the judge. “I am sure some one is searching for her. Poor girl, I will be good to her, for she looks like my sister, who is dead.”

There was a hush for a moment after this announcement, and the officers glanced at me more kindly, while I silently blessed the kind-hearted judge, and hoped that any poor creatures who might be afflicted as I pretended to be should have as kindly a man to deal with as Judge Duffy.

“I wish the reporters were here,” he said at last. “They would be able to find out something about her.”

I got very much frightened at this, for if there is any one who can ferret out a mystery it is a reporter. I felt that I would rather face a mass of expert doctors, policemen, and detectives than two bright specimens of my craft, so I said:

“I don’t see why all this is needed to help me find my trunks. These men are impudent, and I do not want to be stared at. I will go away. I don’t want to stay here.”

So saying, I pulled down my veil and secretly hoped the reporters would be detained elsewhere until I was sent to the asylum.

“I don’t know what to do with the poor child,” said the worried judge. “She must be taken care of.”

“Send her to the Island,” suggested one of the officers.

“Oh, don’t!” said Mrs. Stanard, in evident alarm. “Don’t! She is a lady and it would kill her to be put on the Island.”

For once I felt like shaking the good woman. To think the Island was just the place I wanted to reach and here she was trying to keep me from going there! It was very kind of her, but rather provoking under the circumstances.

“There has been some foul work here,” said the judge. “I believe this child has been drugged and brought to this city. Make out the papers and we will send her to Bellevue for examination. Probably in a few days the effect of the drug will pass off and she will be able to tell us a story that will be startling. If the reporters would only come!”

I dreaded them, so I said something about not wishing to stay there any longer to be gazed at. Judge Duffy then told Policeman Bockert to take me to the back office. After we were seated there Judge Duffy came in and asked me if my home was in Cuba.

“Yes,” I replied, with a smile. “How did you know?”

“Oh, I knew it, my dear. Now, tell me were was it? In what part of Cuba?”

“On the hacienda,” I replied.

“Ah,” said the judge, “on a farm. Do you remember Havana?”

“Si, senor,” I answered; “it is near home. How did you know?”

“Oh, I knew all about it. Now, won’t you tell me the name of your home?” he asked, persuasively.

“That’s what I forget,” I answered, sadly. “I have a headache all the time, and it makes me forget things. I don’t want them to trouble me. Everybody is asking me questions, and it makes my head worse,” and in truth it did.

“Well, no one shall trouble you any more. Sit down here and rest awhile,” and the genial judge left me alone with Mrs. Stanard.

Just then an officer came in with a reporter. I was so frightened, and thought I would be recognized as a journalist, so I turned my head away and said, “I don’t want to see any reporters; I will not see any; the judge said I was not to be troubled.”

“Well, there is no insanity in that,” said the man who had brought the reporter, and together they left the room. Once again I had a fit of fear. Had I gone too far in not wanting to see a reporter, and was my sanity detected? If I had given the impression that I was sane, I was determined to undo it, so I jumped up and ran back and forward through the office, Mrs. Stanard clinging terrified to my arm.

“I won’t stay here; I want my trunks! Why do they bother me with so many people?” and thus I kept on until the ambulance surgeon came in, accompanied by the judge.

Ten Days in a Mad-House

(Chapter IV: Judge Duffy and the Police)

by Nellie Bly (1864 – 1922)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Bly, Nellie, Nellie Bly, Psychiatric hospitals

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature