Fleurs du Mal Magazine

William Shakespeare

Sonnet 130

My mistress’ eyes are nothing like the sun,

Coral is far more red, than her lips red,

If snow be white, why then her breasts are dun:

If hairs be wires, black wires grow on her head:

I have seen roses damasked, red and white,

But no such roses see I in her cheeks,

And in some perfumes is there more delight,

Than in the breath that from my mistress reeks.

I love to hear her speak, yet well I know,

That music hath a far more pleasing sound:

I grant I never saw a goddess go,

My mistress when she walks treads on the ground.

And yet by heaven I think my love as rare,

As any she belied with false compare.

William Shakespeare

Sonnet 130

Geen zonlicht gloeit in ‘t oog van wie ik hou,

Nooit wordt haar liprood met koraal verward,

Is sneeuw soms wit, dan zijn haar borsten grauw,

Is hoofdhaar draad, dan zijn haar draden zwart;

Gevlamde rozen ken ik, rood en wit,

Maar haar wang toont geen roos die zo ontluikt,

Er zijn parfums waar zoeter geur in zit

Dan waar de adem van mijn lief naar ruikt.

Al houd ik van haar stem, ik zie goed in,

Muziekklank zweeft veel aangenamer rond;

‘t Is waar, gaan zag ik nooit nog een godin,

Als mijn lief wandelt treedt ze op de grond.

En toch, bij God, ik acht mijn lief zo hoog,

Als elke vrouw bedot met vals vertoog.

(nieuwe vertaling Cornelis W. Schoneveld, mei 2012)

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: -Shakespeare Sonnets, Shakespeare

Nick J. Swarth

Babyscherven (barsten als die jongens)

Hij werd onthoofd door een tunnel.

Het was de enige keer dat ik hem zag

blèren. Bloed.

Zijn poriën openden zich. In de kleinste

stond een fiedelkast van toen.

Als je wilt huilen moet je het nu doen,

zei niemand in het bijzonder tot iemand

zonder naam.

De jongens waren mooi destijds, ik ook.

De herder van de wacht had een glanzende vacht.

De lege hal was leeg, minimaal een minuut, maar

ogenschijnlijk een eeuw.

De roltrappen rolden en ratelden ongerijmd.

Ik was blijven zitten TOEVALLIG

bij haar pakken, haar zakken, haar zooi.

En zij DE BEDELGRIJS gaf me bij terugkeer,

een kleine drie kwartier na haar vertrek, twee

dollar.

You’ve been keeping an eye on it, good!

De haan kraait, de kraai moet worden gegeten

ANDERS ZOU IK HET OOK NIET WETEN

Om de hoek een man.

Volgens hem liet hij de baby per ongeluk vallen.

Boodschappen stapelen de vaat.

Waarom doen. Morgen is alles weer vies.

(uit: Nick J. Swarth: MIJN ONSTERFELIJKE LEVER. Gedichten & tekeningen. Uitgeverij IJzer, Utrecht | 2012. ISBN 978 90 8684 086 1 – NUR 305 – Paperback, 64 blz. Prijs: € 10 – Zie voor meer informatie: www.swarth.nl )

Op YouTube een video-opname van de presentatie van de nieuwe bundel Mijn onsterfelijke lever

Nick J. Swarth poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Swarth, Nick J.

Joep Eijkens

In Memoriam Riet van Beurden (1926-2012)

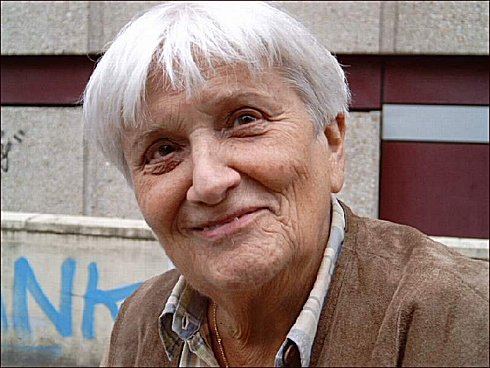

Riet, 29 januari 2003.

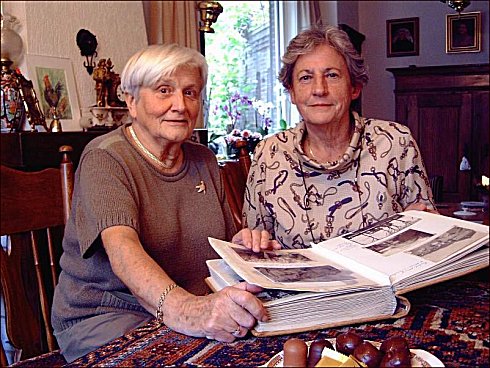

Riet samen met haar ‘evacuatievriendin’ Nelleke Wiltingh herinneringen ophalend aan oorlog en bevrijding.

Riet en Adje die ze nog kende van sociaal pension Transvaalplein.

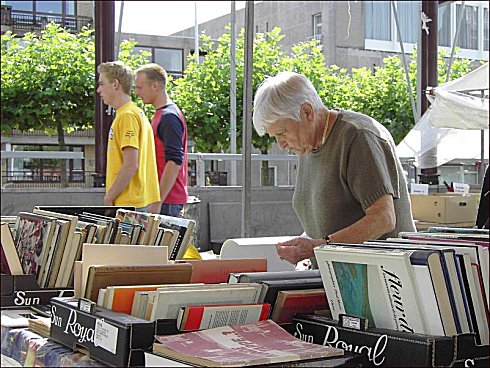

Riet bij mijn jaarlijkse boekenkraam op het Willemsplein in gesprek met dichter Jef van Kempen en fotograaf Wijnand van Lieshout.

Riet en haar buurvrouw Paula met wie ze zoveel lief en leed deelde.

Riet met Lotje 2, het onafscheidelijke poedeltje dat ze zo verwende.

Riet op haar tachtigste verjaardag.

Riet aan de wandel met Lotje 2.

Riet voor haar huis. ‘Verdorie waar blijft onze historie?’ staat er op de poster voor het raam.

Riet bij het portret van Peer de Koning, de boerenknecht die ze in Goirle ‘Pietje de Vuilik’ noemden.

Riet in haar tuin waar ze ook kippen hield.

Riet met Angelique, de vrouw van Gerrit Poels, de Broodpater.

Riet, voorjaar 2010.

Riet met 1ejaars psychologiestudenten die Tilburg verkennen.

Riet met Adje die ook ouder wordt.

Riet tijdens de reünie van oud-bewoners van De Koningswei.

Zo zouden de bijschriften kunnen luiden bij een deel van de foto’s die ik de afgelopen tien jaar bij diverse gelegenheden maakte van Riet van Beurden. Een markante Tilburgse wier naam voor altijd verbonden is met het behoud van Huize Nazareth waar ze tegenover woonde in de Nazarethstraat.

Nu ik al die foto’s waar Riet op staat terugzie, vind ik haar er zorgelijker uitzien dan ik me herinner. Misschien vond ze het niet zo leuk om op de foto te gaan. Misschien associeerde ze het op de foto gaan met ernstig kijken, serieus zijn. Bovendien had ze nu eenmaal haar momenten dat ze zich kwaad maakte en dan zag je niet de vrolijke, enthousiaste, levendige vrouw zoals ze toch op de eerste plaats in mij voortleeft.

Waar ze zich druk of kwaad om maakte? Niet op de laatste plaats om mensen die anderen het leven zuur maakten. Riet van Beurden had een groot rechtvaardigheidsgevoel en kwam altijd op voor de mensen die het minder goed getroffen hadden. ‘Ik ben zo blij dat ik sociaal voelende ouders heb gehad’, vertrouwde ze me eens toe. Ze mocht dan wel ooit gezelschapsjuffrouw zijn geweest bij een rijke dame op een kasteel, haar mooiste jaren bracht ze als vrijwilligster door tussen zwervers, junks, daklozen en alleenstaande moeders met kinderen in sociaal pension Transvaalplein.

Wijnand van Lieshout noemde haar ‘een Coba Pulskens-typeke’. Een beetje oneerbiedig? Nee hoor, zo had de Tilburgse kunstenaar het zeker niet bedoeld. Riet van Beurden had in elk geval ook het strijdbare van Tilburgs bekendste verzetsstrijdster.

Ze zal al tegen de zestig gelopen hebben toen ik voor de eerste keer kennis met haar maakte. Ik werkte toen bij het Nieuwsblad van het Zuiden (later: Brabants Dagblad) waar ik onder meer schreef over onderwerpen uit de Tilburgse geschiedenis. Nou, heemkunde en historie waren een kolfje naar Riets hand. En dat liet ze merken. Ik weet niet hoe vaak ik gebeld werd op de krant. En als je ze eenmaal aan de lijn had, was je zomaar niet van haar af. Want Riet had altijd wat meegemaakt en zat vol mooie verhalen. Ik heb haar wel eens gezegd dat ze alles eens op papier moest zetten – maar daar was het de vrouw niet naar. Ze vond het gewoon leuk om te vertellen. Dat zal ik, denk ik, ook het meest missen: gewoon even bij Riet langs, even op de koffie en luisteren. En lachen. Het waren nu eenmaal vaak verhalen van een lach en een traan.

Wél viel me op dat ze de laatste jaren wel eens minder vrolijk gestemd was. Natuurlijk had dat ook te maken met gezondheidsproblemen. Maar werd ze ook niet pessimistischer? Ook de vele krantenartikelen over seksueel misbruik in de katholieke kerk vielen haar zwaar. Zelfs de Fraters van Tilburg bleken erbij betrokken, nota bene van hetzelfde Huize Nazareth dat mede dankzij haar inzet gespaard was gebleven voor de slopershamer. Maar ik geloof dat ze ook wel bleef vinden dat het meeste wat de fraters gedaan hadden voor Tilburg goed was.

De laatste keer dat ik haar fotografeerde was afgelopen najaar tijdens een mooie reünie van oud-bewoners van de roemruchte volkswijk De Koningswei. Het was denk ik al geen goed teken dat ze er maar even haar gezicht liet zien.

Daarna kwam ik haar nog een paar keer tegen op straat met haar onafscheidelijk Lotje 2.

Ja, ik heb nog een paar foto’s van haar gemaakt. Maar dat was op 25 mei j.l. toen ze opgebaard lag in een rouwcentrum.

De dag erna kreeg ze een mooie uitvaartdienst in de Heikese kerk. En vond ze tenslotte een laatste rustplaats op begraafplaats St. Jan te Goirle, naast haar ouders. Het kind is weer thuis. Een mooi kind, een goed mens. Ik ben dankbaar dat ik haar mee heb mogen maken.

In dankbare herinnering aan Riet van Beurden (1926-2012)

Joep Eijkens foto’s & tekst

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: In Memoriam, Joep Eijkens Photos, The talk of the town

Theodor Fontane

(1819–1898)

Im Garten

Die hohen Himbeerwände

Trennten dich und mich,

Doch im Laubwerk unsre Hände

Fanden von selber sich.

Die Hecke konnt’ es nicht wehren,

Wie hoch sie immer stund:

Ich reichte dir die Beeren,

Und du reichtest mir deinen Mund.

Ach, schrittest du durch den Garten

Noch einmal im raschen Gang,

Wie gerne wollt’ ich warten,

Warten stundenlang.

Theodor Fontane poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive E-F, Theodor Fontane

J.A. Woolf: Making memories (16)

kempis.nl poetry magazine 2012

More in: J.A. Woolf

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (17)

Shoot! (Si Gira, 1926) The Notebooks of Serafino Gubbio, Cinematograph Operator by Luigi Pirandello. Translated from the Italian by C. K. Scott Moncrieff.

BOOK III

6

It is not so much for me, Gubbio, this antipathy, as for my machine. It recoils upon me, because I am the man who turns the handle.

They do not realise it clearly, but I, with the handle in my hand, am to them in reality a sort of executioner.

Each of them–I refer, of course, to the real actors, to those, that is to say, who really love their art, whatever their merits may be–is here against his will, is here because he is better paid, and for work which, even if it requires some exertion, does not call for any intellectual effort. Often, as I have said before, they do not even know what part they are playing.

The machine, with the enormous profits that it produces, if it engages them, can reward them far better than any manager or proprietor of a dramatic company. Not only that; but it, with its mechanical reproduction, being able to offer at a low price to the general public a spectacle that is always new, fills the cinematograph halls and empties the theatres, so that all, or nearly all the dramatic companies are now doing wretched business; and the actors, if they are not to starve, see themselves compelled to knock at the doors of the cinematograph companies. But they do not hate the machine merely for the degradation of the stupid and silent work to which it condemns them; they hate it, first and foremost, because they see themselves withdrawn, feel themselves torn from that direct communion with the public from which in the past they derived their richest reward, their greatest satisfaction: that of seeing, of hearing from the stage, in a theatre, an eager, anxious multitude follow their ‘live’ action, stirred with emotion, tremble, laugh, become excited, break out in applause.

Here they feel as though they were in exile. In exile, not only from the stage, but also in a sense from themselves. Because their action, the ‘live’ action of their ‘live’ bodies, there, on the screen of the cinematograph, no longer exists: it is ‘their image’ alone, caught in a moment, in a gesture, an expression, that flickers and disappears.

They are confusedly aware, with a maddening, indefinable sense of emptiness, that their bodies are so to speak subtracted, suppressed, deprived of their reality, of breath, of voice, of the sound that they make in moving about, to become only a dumb image which quivers for a moment on the screen and disappears, in silence, in an instant, like an unsubstantial phantom, the play of illusion upon a dingy sheet of cloth.

They feel that they too are slaves to this strident machine, which suggests on its knock-kneed tripod a huge spider watching for its prey, a spider that sucks in and absorbs their live reality to render it up an evanescent, momentary appearance, the play of a mechanical illusion in the eyes of the public. And the man who strips them of their reality and offers it as food to the machine; who reduces their bodies to phantoms, who is he? It is I, Gubbio.

They remain here, as on a daylight stage, when they rehearse. The first night, for them, never arrives. The public they never see again. The machine is responsible for the performance before the public, with their phantoms; and they have to be content with performing only before it. When they have performed their parts, their performance is film.

Can they feel any affection for me?

A certain comfort they have for their degradation in seeing not themselves only subjugated to the service of this machine, which moves, stirs, attracts ever so many people round it. Eminent authors, dramatists, poets, novelists, come here, all of them regularly and solemnly proposing the “artistic regeneration” of the industry. And to all of them Commendator Borgalli speaks in one tone, and Cocò Polacco in another: the former, with the gloved hands of a General Manager; the other, openly, as a stage manager. He listens patiently, does Cocò Polacco, to all their suggestions of plots; but at a certain stage in the discussion he raises his hand, saying:

“Oh no, that is a trifle crude. We must always keep an eye on the English, my dear Sir!”

A most brilliant discovery, this of the English. Indeed the majority of the films produced by the Kosmograph go to England. We must therefore, in selecting our plots, adapt ourselves to English taste. And is there any limit to the things that the English will not have in a film, according to Cocò Polacco?

“English prudery, you understand! They have only to say’shocking,’ and there’s an end of the matter!”

If the films went straight before the judgment of the public, then, perhaps, many things might pass; but no: for the importation of films into England there are the agents, there is the reef, the pitfall of the agents. They decide, the agents, and there is no appeal. And for every film that will not ‘go’, there are hundreds of thousands of lire wasted or not forthcoming.

Or else Cocò Polacco exclaims:

“Excellent! But that, my dear fellow, is a play, a perfect play! A certain success! Do you want to make a film of it? I won’t hear of it! As a film it won’t go: I tell you, my dear fellow, it’s too subtle, too subtle. That is not the sort of thing we want here! You are too clever, and you know it.”

In short, Cocò Polacco, if he refuses their plots, pays them a compliment: he tells them that they are not stupid enough to write for the cinematograph. From one point of view, therefore, they would like to understand, would resign themselves to understanding; but, from another, they would like also to have their plots accepted. A hundred, two hundred and fifty, three hundred lire, at certain moments…. The suspicion that this praise of their intelligence and depreciation of the cinematograph as a form of art have been advanced as a polite way of refusing their plots flashes across the minds of some of them; but their dignity is saved and they can go away with their heads erect. As they pass, the actors salute them as companions in misfortune.

“Everyone has to pass through here!” they think to themselves with malicious joy. “Even crowned heads! All of them in here, printed for a moment on a sheet!”

A few days ago, I was with Fantappie in the courtyard on which the rehearsal theatre and the office of the Art Department open, when we noticed an old man with long hair, in a tall hat, with a huge nose and eyes that peered through his gold-rimmed spectacles, and a straggling beard, who seemed to be shrinking into himself with fear at the big coloured posters pasted on the wall, red, yellow, blue, glaring, terrible, of the films that have brought most honour to the firm.

“Illustrious Senator,” Fantappie exclaimed with a bound, springing towards him and then bringing himself to attention, his hand comically raised in the military salute. “Have you come for the rehearsal?”

“Why… yes… they told me ten o’clock,” replied the illustrious Senator, endeavouring to make out whom he was addressing.

“Ten o’clock? Who told you that! The Pole?”

“I don’t understand…”

“The Pole, the producer!”

“No, an Italian… one they call the engineer. …”

“Ah! Now I know: Bertini! He told you ten o’clock? That’s all right. It is half past ten now. He’s sure to be here by eleven.”

It was the venerable Professor Zeme, the eminent astronomer, head of the Observatory and a Member of the Senate, an Academician of the Lincei, covered with ever so many Italian and foreign decorations, invited to all the Court banquets.

“Excuse me, though, Senator,” went on that buffoon Fantappiè. “May I ask one favour: couldn’t you make me go to the Moon?”

“I? To the Moon?”

“Yes, I mean cinematographically, you know … ‘Fantappiè in the Moon’: it would be lovely! Scouting, with a patrol of eight men. Think it over, Senator. I would arrange the business. … No? You say no?”

Senator Zeme said no, with a wave of the hand, if not contemptuously, certainly with great austerity. A scientist of his standing could not allow himself to place his science at the service of a clown. He has allowed himself, it is true, to be taken in every conceivable attitude in his Observatory; he has even asked to have projected on the screen a page containing the signatures of the most illustrious visitors to the Observatory, so that the public may read there the signatures of T.M. the King and Queen and of T. E. H. the Crown Prince and the Princesses and of H. M. the King of Spain and of other Kings and Cabinet Ministers and Ambassadors; but all this to the greater glory of his science and to give the public some sort of idea of the ‘Marvels of the Heavens’ (the title of the film) and of the formidable greatness in the midst of which he, Senator Zeme, insignificant little creature as he is, lives and labours.

“Martuf!” muttered Fantappiè, like a good Piedmontese, with one of his characteristic grimaces, as he strolled away with me.

But we turned back, a moment later, at the sound of a great clamour of voices which had arisen in the courtyard.

Actors, actresses, operators, producers, stage hands had come pouring out from the dressing-rooms and rehearsal theatre and were gathered round Senator Zeme at loggerheads with Simone Pau, who is in the habit of coming to see me now and again at the Kosmograph.

“Educating the people, indeed!” shouted Simone Pau. “Do me a favour! Send Fantappiè to the Moon! Make him play skittles with the stars! Or perhaps you think that they belong to you, the stars? Hand them over here to the divine Folly of man, which has every right to appropriate them and to play skittles with them! Besides… excuse me, but what do you do? What do you suppose you are? You see nothing but the object! You have no consciousness of anything but the object! And so, a religion. And your God is your telescope! You imagine that it is your instrument? Not a bit of it! It is your God, and you worship it! You are like Gubbio here, with his machine! The servant. … I don’t wish to hurt your feelings, let me say the priest, the supreme pontiff (does that satisfy you?) of this God of yours, and you swear by the dogma of its infallibility. Where is Gubbio? Three cheers for Gubbio! Wait, don’t go away, Senator! I came here this morning, to comfort an unhappy man. I made an appointment with him here: he ought to be here by now. An unhappy man, my fellow-lodger in the Falcon Hostelry…. There is no better way of comforting an unhappy man, than by proving to him by actual contact that he is not alone. So I–have invited him here, among these good artist friends. He is an artist too! Here he comes!”

And the man with the violin, long and lanky, bowed and sombre, whom I first saw more than a year ago in the Casual Shelter, came forward, apparently absorbed as before in gazing at the hairs that drooped from his bushy, frowning brows.

The crowd made way for him. In the silence that had fallen, a titter of merriment sounded here and there. But stupefaction and a certain sense of revulsion held most of us spellbound as we watched this man come towards us with bent head, his eyes fastened like that on the hairs of his eyebrows, as though he refused to look at his red, fleshy nose, the enormous burden and punishment of his intemperance. More than ever, now, as he advanced, he seemed to be saying:

“Silence! Make way! You see what life can bring a man’s nose to?”

Simone Pau introduced him to Senator Zeme, who made off, indignant; everyone laughed, but Simone Pau, quite serious, went on introducing him to the actresses, the actors, the producers, relating to one and another of them in snatches the story of his friend’s life, and how and why, after that last famous rebuff, he had never played again. Finally, thoroughly aroused, he shouted:

“But he will play to-day, ladies and gentlemen! He will play! He will break the evil spell! He has promised me that he will play! But not to you, ladies and gentlemen! You will keep in the background. He has promised me that he will play to the tiger. Yes, yes, to the tiger! To the tiger! We must respect his wishes. He is certain to have excellent reasons for them! Come along, come along now all of you…. We must keep in the background…. He shall go in, by himself, in front of the cage, and play!”

Amid shouts, laughter, applause, impelled, all of us, by the keenest curiosity as to this strange adventure, we followed Simone Pau, who had taken his man by the arm and was urging him on, following the instructions shouted at him from behind, telling him the way to the menagerie. On coming in sight of the cages he stopped us all, bidding us be silent, and sent on ahead, by himself, the man with the violin.

At the sound of our coming, from shops and stores, workmen, stage hands, scene painters came running out in full force to watch the scene over our shoulders: there was quite a crowd.

The animal had withdrawn with a bound to the back of its cage; and crouched there with arched back, lowered head, snarling teeth, bared claws, ready to spring: terrible!

The man stood gazing at it, speechless; then turned in bewilderment and let his eyes range over us in search of Simone Pau.

“Play!” Simone shouted at him. “Don’t be afraid! Play! She will understand you!”

Whereupon the man, as though freeing himself by a tremendous effort from an obsession, at length raised his head, shook it, flung his shapeless hat on the ground, passed a hand over his long, unkemptlocks, took the violin from its old green baize cover, and threw the cover’down also, on top of his hat.

A catcall or two came from the workmen who had crowded in behind us, followed by laughter and comments, while he tuned his violin; but a great silence fell as soon as he began to play, at first a little uncertainly, hesitating, as though he felt hurt by the sound of his instrument which he had not heard for so long; then, all of a sudden, overcoming his uncertainty, and perhaps his painful tremors with a few vigorous strokes. These strokes were followed by a sort of groan of anguish, that grew steadily louder, more insistent, strange notes, harsh and toneless, a tight coil, from which every now and then a single note emerged to prolong itself, like a person trying to breathe a sigh amid sobs. Finally this note spread, developed, let itself go, freed from its suffocation, in a phrase melodious, limpid, honey-sweet, intense, throbbing with infinite pain: and then a profound emotion swept over us all, which in Simone Pau took the form of tears. Raising his arms he signalled to us to keep quiet, not to betray our admiration in any way, so that in the silence this queer, marvellous wastrel might listen to the voice of his soul.

It did not last long. He let his hands fall, as though exhausted, with the violin and bow, and turned to us with a face transfigured, bathed in tears, saying:

“There…”

The applause was deafening. He was seized, carried off in triumph. Then, taken to the neighbouring tavern, notwithstanding the prayers and threats of Simone Pau, he drank and lost his senses.

Polacco was kicking himself with rage, at not having thought of sending me off at once to fetch my machine to place on record this scene of serenading the tiger.

How perfectly he understands everything, always, Cocò Polacco! I was not able to answer him because I was thinking of the eyes of Signora Nestoroff, who had looked on at the scene, as though in an ecstasy instinct with terror.

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (17)

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: -Shoot!

Ai Weiwei,

the artist, the philosopher and the rebel

Museum De Pont until june 24, 2012

Ai Weiwei (1957) is an artist, a philosopher and a rebel. It runs in the family. His father was a writer and a poet who was forced to live in exile in a labor camp for over 16 years. Ai Weiwei received his education in China and lived in the USA from 1981 to 1993. When his father became ill he returned to China. His art is multifacated and a challenge for our associative talents. He currently has a very inspiring show at Museum de Pont which is on view through 24 June.

Ai Weiwei’s art is about China, but his art is not the Chinese art that became popular during the late eighties and the nineties, with the cynical and caricatural paintings by for instance Fan Lijun and Yue Minjun, colorful paintings, crowded with bald headed, smiling, blunted figures. Ai Weiwei is not a painter, he has embraced the concept that art can be expressed in any way or form. In some of his videos he uses today’s reality in China as a ready-made, like Duchamp and Warhol before him, a registration of reality as it is, only ‘manipulated’ by the choice of subject.

Beijing is a 150 hour film of a 2400 km taxi drive, crossing a district of Beijing. The film shows a public space dominated by inanimate architecture, by motorways and cars, a view not different from any modern western city. The Chinese ornament hanging down from the cab’s rear mirror questions the scarce presence of remainders of traditional Chinese culture and architecture.

The Second Ring is a 66 minute film taken from the 33 bridges that cross the second ring in Beijing, 1 minute of film in each direction. It is an objective depiction of this fragment of reality without any explicit comment. The film leaves any questioning or commenting to us, to the viewer.

I’m not an analyst, my art is intuitive, of course I have put certain ideas into the works but they may not be the most important aspect. That is for other people to decide.

His art is Chinese, he acknowledges the skills, the craftsmanship of the Chinese cultural tradition, works of art from the past reflect as he puts it: the morality, the aesthetics and the philosophy of its time. He uses elements of this tradition and connects them to contemporary social-political issues, for instance by reconstructing trees as if museums are becoming the only save havens for conserving nature, just as they are for conserving important art. The Forever-bicycles sculpture integrates ready-mades into a carousel or is it a treadmill, it seems a metaphor for the absence of a strong believe in individuality in Chinese culture. And in his most famous work, the hundreds of thousands of painted sunflower seeds, Ai Weiwei suggests a modern form of slavery, a contemporary form in which the western 17/18th century Chine de Commande porcelain has been replaced by shirts, shorts and shoes.

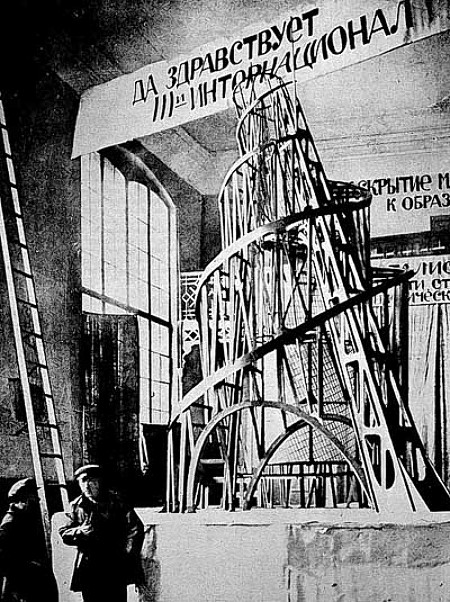

Ai Weiwei’s Fountain of Light is a Chinese version of Tatlin’s Monument to the Third International, a symbol of modernity and a tribute to the Bolshewik Revolution of 1917. Weiwei’s monstrous sculpture addresses the audacity, the self-glorification of ideologies and the complete absence of any appropriate humility.

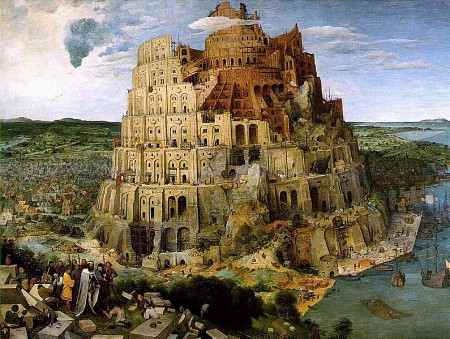

Pieter Breughel, Tower of Babel

Model of Tatlin’s Monument

Fountain of Light (at Museum De Pont)

Text & photos: Anton K.

De Pont museum of contemporary art:

Ai Weiwei until 24 June 2012

Berlin, Linienstrasse, protest against Ai Weiwei’s arrest, April 2011

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Ai Weiwei, Anton K. Photos & Observations, Exhibition Archive, REPRESSION OF WRITERS, JOURNALISTS & ARTISTS, Sculpture

More in: The Art of Reading, The talk of the town

Iers gedicht ‘Cride hé’

vertaald door Lauran Toorians

Cride hé,

daire cnó,

ócán é,

pócán dó.

Hij is mijn hart,

mijn bosje notelaren,

hij is mijn jongen,

een zoen voor hem.

Middeleeuwse Ierse gedichten vertaald door Lauran Toorians

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: CELTIC LITERATURE, Lauran Toorians

William Shakespeare

(1564-1616)

THE SONNETS

130

My mistress’ eyes are nothing like the sun,

Coral is far more red, than her lips red,

If snow be white, why then her breasts are dun:

If hairs be wires, black wires grow on her head:

I have seen roses damasked, red and white,

But no such roses see I in her cheeks,

And in some perfumes is there more delight,

Than in the breath that from my mistress reeks.

I love to hear her speak, yet well I know,

That music hath a far more pleasing sound:

I grant I never saw a goddess go,

My mistress when she walks treads on the ground.

And yet by heaven I think my love as rare,

As any she belied with false compare.

![]()

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: -Shakespeare Sonnets

Vinko Kalinić

Pola pjesme

Probudio sam se jutros s pola pjesme u glavi

pamtim, sanjao sam te – da, bile su to tvoje usne

i ruke! i nos! i uho! – i mogao bih napisati pjesmu

sasvim strašnu neku pjesmu, pristojnu i zanosnu

recimo, o čovjeku koji je umro u snu, ljubeći te

ali ne znam kako ti oči pretočiti u riječi

te strašne oči koje me uvijek iz nova prepolove

na mene koji bi umro zbog njih

i na mene koji bi umro bez njih

– oči, pred kojima ni jedna pjesma

nikada neće biti ispjevana do kraja

Komiža, 20. 11. 2010

Half a song

I woke up this morning with half a song in my head

I remember, I dreamt about you – yes, those were your lips

and hands! and nose! and ear! – and I could write a song

some absolutely dreadful song, decent and passionate

let’s say, about a man who died in his dream, while kissing you

but I don’t know how to transfuse your eyes into words,

those enticing eyes which bisect me in two all over again,

to a me that would die for them

and to a me that would die without them

– those eyes, in front of which no song

will ever be sung till the end

Translation by Darko Kotevski, Melbourne

Vinko Kalinić poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive K-L, Kalinić, Vinko

Schrijf het mooiste stadsgedicht voor de stadsgedichtenwedstrijd 2012

Je houdt van een stad, je bent trots op een stad, je haat een stad, je bent jaloers op een stad of hebt er andere gevoelens over. Verwoordt die beleving in een gedicht en doe mee aan de Stadsgedichtenwedstrijd 2012 en maak zo kans op een uiterst aantrekkelijke prijs en publicatie in een bijzondere dichtbundel.

Dit jaar organiseert de Stichting Poëtikos op zaterdag 8 september voor de 8e keer in successie de Nationale Stadsdichtersdag in Lelystad. Officieel door B&W benoemde Stadsdichters in Nederland en Belgisch Vlaanderen komen dan naar de Flevolandse provinciehoofdstad om daar hun bijzondere poëzie aan publiek en genodigden ten gehore te brengen. Een uniek evenement dat de veelzijdigheid van poëzie en het Stadsdichterschap in het bijzonder, in al zijn diversiteit presenteert.

Niet alleen officieel benoemde Stadsdichters dichten over hun stad. Voor alle anderen die dat ook doen heeft de Stichting Poëtikos, in samenwerking met Uitgeverij Kontrast, dit jaar de Stadsgedichtenwedstrijd 2012 georganiseerd. Een uitdaging aan een ieder die een stad in Nederland of Vlaanderen een bepaald gevoel toedraagt en daarover een gedicht wil schrijven. Neem de spreekwoordelijke pen op, denk aan de stad waar je woont of een stad die, op welke wijze dan ook, opmerkelijk voor je is. Je kunt een stad liefhebben, verafschuwen, missen of alleen maar kennen van een foto. Waar het om gaat is dat de stad emoties bij je oproept en je inspireert bij het schrijven van een gedicht. Voor stad mag ook dorp gelezen worden.

Tot 15 augustus 2012 mogen de mooiste, vreemdste, lelijkste, verdrietigste (enzovoort) stadsgedichten ingestuurd worden. Een deskundige jury zal daarna de gedichten beoordelen. Op zaterdag 8 september, tijdens het avondprogramma van de Nationale Stadsdichtersdag in het vermaarde Agora Theater in Lelystad, zullen de prijswinnaars bekend worden gemaakt. Er zijn drie prijzen te winnen: de eerste prijs is € 500,00 de tweede prijs is € 250,00 en de derde prijs is € 100,00. Deelname aan deze Stadsgedichtenwedstrijd biedt de mogelijkheid op toegang tot de slotmanifestatie van de 8e Nationale Stadsdichtersdag in Lelystad.

• Website stadsgedichtenwedstrijd

• Reglement stadsgedichtenwedstrijd

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: City Poets / Stadsdichters

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature