Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Zes genominerden voor AKO Literatuurprijs 2013

De namen van de genomineerden voor de AKO Literatuurprijs 2013 zijn bekend. De zes genomineerden zijn: Martin Bossenbroek (De Boerenoorlog), Jan Brokken (De vergelding), Wouter Godijn (Hoe ik een beroemde Nederlander werd), Joke van Leeuwen (Feest van het begin), Ilja Leonard Pfeijffer (La Superba) en Allard Schröder (De dode arm). Dat heeft juryvoorzitter Patrick Janssens vrijdagavond bekendgemaakt.

Op 28 oktober wordt de winnaar bekendgemaakt. Vorig jaar ging de prijs naar de Belg Peter Terrin voor zijn boek Post mortem.

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, Art & Literature News

DICHTER AAN HUIS

literair festival in Den Haag

50 schrijvers & 50 locaties

Op zaterdag 5 en zondag 6 oktober vindt in Den Haag literair festival Dichter aan huis plaats. Vijftig gerenommeerde schrijvers, columnisten, poëten, thrillerschrijvers, biografen etc. lezen voor uit eigen werk, vier keer per dag: de eerste lezing is om 13.00 uur, dan om 14.00 uur, 15.00 uur en de laatste om 16.00 uur. Na de voordracht van circa 25 minuten heeft u nog ruimschoots de gelegenheid om met de schrijver van gedachten te wisselen. Elke bijeenkomst duur maximaal 45 minuten, daarna heeft u ruimschoots de tijd naar een volgende locatie te gaan.

De locaties zijn gesitueerd in en rond het centrum van Den Haag. Zo openen huizen in de chique Archipelbuurt hun deuren en kunt u een kijkje nemen in het artistieke Zeeheldenkwartier. U kunt niet alleen genieten van de schrijver maar ook een kijkje kunt nemen achter bijzondere voordeuren. Er wacht u een zeer gastvrije ontvangst door de gastvrouwen en –heren.

Met elke dag 25 schrijvers die ieder vier keer achter elkaar optreden is er keuze te over. Treft u onverhoopt toch een bordje VOL bij een adres aan, dan wijkt u uit naar een andere auteur van uw keuze. U krijgt vanaf begin september de plattegrond toegestuurd zodat u al tijdig uw route kunt bepalen. De locaties liggen op loop-, dan wel fietsafstand.

Alle meewerkende schrijvers hebben een bijdrage geleverd aan de bloemlezing die speciaal voor Dichter aan huis is samengesteld. het resultaat is een prachtig boekwerkje met inspirerende gedichten en verhalen. U kunt de bundel direct bestellen bij uw kaarten of vanaf 1 september via www.freemusketeers.nl De kosten per bundel bedragen € 17,95.

Deelnemende schrijvers: Arie Boomsma – Renske de Greef – Maxim Februari – Abdelkader Benali – Erik Menkveld – F. Starik – Jan Rot – Kees ‘t Hart – Koos van Zomeren – Menno Wigman – Annemarie Oster – Reggie Baay – Herman Pleij – Arjen Duinker – Jan Kuitenbrouwer – Lieke Marsman – Wim Hofman – Marcel Möring – Ted van Lieshout – Irene Wiersma – Annemiek Schrijver – Saskia Goldschmidt – Tomas Lieske – Anne Büdgen – Paul van Vliet – Hans Goedkoop – Wim Daniëls – Tjitske Jansen – Ilja Leonard Pfeijffer – Jean Pierre Rawie – René Diekstra – Asis Aynan – Ruben van Gogh – Max Pam – Jessica Durlacher – Marjolijn van Heemstra – Kira Wuck – Christiaan Weijts – Ellen Deckwitz – Petra Stienen – Charlotte Mutsaers – Miquel Bulnes – Özcan Akyol – Mischa Andriessen – Sjaak Bral – Yvonne keuls – Jan Baeke – Mijndert Talma – Marion Bloem – Piet Meeuse

# Kaartverkoop etc. zie website DICHTER AAN HUIS

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Art & Literature News

![]()

Babelmatrix Translation Project

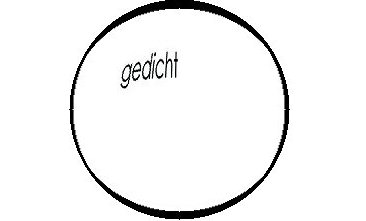

Imre Kertész

Imre Kertész was born in Budapest on November 9, 1929. Of Jewish descent, in 1944 he was deported to Auschwitz and from there to Buchenwald, where he was liberated in 1945. On his return to Hungary he worked for a Budapest newspaper, Világosság, but was dismissed in 1951 when it adopted the Communist party line. After two years of military service he began supporting himself as an independent writer and translator of German-language authors such as Nietzsche, Hofmannsthal, Schnitzler, Freud, Roth, Wittgenstein, and Canetti, who have all had a significant influence on his own writing.

Kertész’s first novel, Sorstalanság (Eng. Fateless, 1992; see WLT 67:4, p. 863), a work based on his experiences in Auschwitz and Buchenwald, was published in 1975. “When I am thinking about a new novel, I always think of Auschwitz,” he has said. This does not mean, however, that Sorstalanság is autobiographical in any simple sense: Kertész says himself that he has used the form of the autobiographical novel but that it is not autobiography. Sorstalanság was initially rejected for publication. When published eventually in 1975, it was received with compact silence. Kertész has written about this experience in A kudarc (1988; Fiasco). This novel is normally regarded as the second volume in a trilogy that begins with Sorstalanság and concludes with Kaddis a meg nem született gyermekért (1990; Eng. Kaddish for a Child Not Born, 1997; see WLT 74:1, p. 205), in a title that refers to the Jewish prayer for the dead. In Kaddis a meg nem született gyermekért, the protagonist of Sorstalanság and A kudarc, György Köves, reappears. His Kaddish is said for the child he refuses to beget in a world that permitted the existence of Auschwitz. Other prose works are A nyomkereso” (1977; The pathfinder) and Az angol labogó (1991; The English flag; see WLT 67:2, p. 412)

Gályanapló (Részletek) (Hungarian)

Ahhoz, hogy valaki – dehogy az „emberiség!” – csupán a saját élete megváltója, föloldozója lehessen, egy teljes, hihetetlenül intenzív és állandó belsö munkával eltöltött élet szükséges. Az embernek van egy förtelmes élete – a történelem-, és van egy nála sokkal bölcsebb, hatalmas világmeséje, amelyben istenséggé, mágussá válik; és ez a mese éppoly csoda, mint amilyen hihetetlen a történelmi, a „reális” élete.

Augusztus 11. Minden véget ért, és minden újrakezdödött; de máshol kezdödött, és talán máshová visz. Tegnapelött éjszaka az erkélyen, hüvösödo” szélfutamok, a Pasaréti úti fák nagy, felhöforma, sötét lombozata, alatta az aranyló világítás – egy pillanatig mintha nem is ez a jól ismert lidércváros lenne. Mély, mély melankólia, emlékek, mintha az elmúlás környékezne, csupa közhely, csupa valóság, csupa unalmas igazság, akár a halál.

L., az író, aki viszonylagosnak fogja fel az irodalmat. Szemben Schönberg nézetével, miszerint a mu”vészethez elég az igazság, L. szerint a müvészetnek a túlélést kell szolgálnia: hiszen, mondja, ha meglátjuk a puszta igazságot, akkor nem marad hátra más, mint hogy felkössük magunkat – vagy netalán azt, aki az igazságot nekünk megmutatta. Nem éppen szokatlan magatartás; nem csodálkoznék, ha L.-ról kiderülne, hogy családapa, s csupán a gyermekei jövo”jéért teszi, amit tennie kell. Csakhogy a viszonylagos irodalom mindig rossz irodalom, és a nem radikális müvészet mindig középszeru” müvészet: jó müvésznek nincs más esélye, mint hogy igazat mondjon, és az igazat radikálisan mondja. Etto”l még életben lehet maradni, hiszen a hazugság nem az egyetlen és kizárólagos föltétele az életnek, ha sokan nem is látnak egyéb lehetöséget.

Mostanában gyakran elképzelek valakit, homályos alak, egy emberi lény, kortalan, persze inkább ido”s vagy legalábbis idösödo” férfi. Jön-megy, végzi a dolgát, éli az életét, szenved, szeret, elutazik, hazatér, olykor beteg, máskor úszni, társaságba, kártyázni jár; mindeközben azonban, amint akad egy szabad perce, tüstént benyit egy eldugott fülkébe, gyorsan – és mintegy szórakozottan – leül valami ócska hangszer elé, leüt néhány akkordot, majd félhalkan improvizálni kezd, évtizedeken keresztül játssza ugyanegy téma immár számtalanadik variációját. Nemsoká felugrik, mennie kell – de amint újabb szabadideje adódik, ismét ott látjuk öt a hangszernél, mintha az élete csak amolyan két játék közötti, kényszer közbevetés lenne. Ha ezek a hangok, amiket a hangszerböl kicsal, mondjuk, megállnának, és egymásba su”ru”södve mintegy megfagynának a levego”ben, talán valami görcsös kataton mozdulatra emlékeztetö jégkristályképzödményt látnánk, amelyben, jobban is megnézve, kétségkívül felismerheto” lenne valamilyen kifejezö szándé makacssága, ha csupán a monotóniáé is; ha meg netán lekottáznák, végül alighanem ki lehetne venni egy mindegyre sürüödo” fúga bontakozó körvonalait, mely mind határozottabban tör célja felé, csakhogy e célt mind távolabbra tolja, taszigálja magától, s így mégis mind bizonytalanabbá válik. – Kinek játszik? Miért játszik? Maga sem tudja. Söt – és azért mégiscsak ez a legfurcsább – nem is hallja, hogy mit játszik. Mintha a kísérteties erö, amely újra meg újra odaparancsolja a hangszerhez, megfosztotta volna a hallásától, hogy egyedül neki játsszon. -De ó legalább hallja-e? (A kérdés azonban, lássuk be, értelmetlen: a játékost természetesen boldognak kell elképzelnünk.)

1992

Galeerentagebuch (Auszüge) (German)

Um Erlöser – keineswegs der »Menschheit«! – lediglich seines eigenen Lebens sein zu können, um sich für das eigene Leben Absolution erteilen zu können, ist ein volles, unsagbar intensives und von ständiger innerer Arbeit erfülltes Leben notwendig. Der Mensch hat ein grauenhaftes Leben – die Geschichte –, und er hat die Erzählung von der Welt, mächtig und viel weiser als er, in der er zur Gottheit, zum Magier wird; und diese Erzählung ist genauso ein Wunder, wie sein geschichtliches, «reales» Leben etwas Unglaubliches ist.

11. August Alles hat ein Ende, und alles begann von vorn; doch es begann anderswo und führt vielleicht anderswohin. Vorgestern nacht auf dem Balkon, ein kühler Wind, das große, wolkenförmige, dunkle Laubdach der Bäume in der Pasareti-Straße, darunter die schummrige Beleuchtung – für einen Moment war mir, als sei es nicht die vertraute Alptraumstadt. Tiefe, tiefe Melancholie, Erinnerungen, als umgebe mich dei Vergänglichkeit, voll Banalität, voll Wirklichkeit, voll langweiliger Wahrheit, wie der Tod.

L., der Schriftsteller, der die Literatur relativ auffaßt. Im Gegensatz zu Schönberg, nach dessen Ansicht Wahrheit für die Kunst genügt, muß die Kunst L. zufolge dem Überleben dienen, denn, sagt er, wenn wir die nackte Wahrheit erblicken, bleibt uns nichts anderes übrig, als uns aufzuhängen – oder vielleicht den, der uns die Wahrheit gezeigt hat. Keine ganz ungewöhnliche Haltung; es würde mich nicht wundern, wenn sich herausstellte, daß L. Familienvater ist und das, was er tut, nur für die Zukunft seiner Kinder tut. Nur daß relative Literatur immer schlechte Literatur und nichtradikale Kunst immer mittelmäßige Kunst ist: Der wirkliche Künstler hat keine andere Chance, als die Wahrheit zu sagen und die Wahrheit radikal zu sagen. Deswegen kann er trotzdem am Leben bleiben, denn die Lüge ist nicht einzige und ausschließliche Bedingung des Lebens, selbst wenn viele keine sonstigen Möglichkeiten sehen.

In letzter Zeit stelle ich mir häufig etwas vor, eine unklare Gestalt, ein menschliche; Wesen, einen alterslosen, freilich eher alten oder doch älteren Mann. Er kommt und geht, erledigt seine Dinge, lebt sein Leben, leidet, liebt, verreist, kehrt heim, manchmal ist er krank, manchmal geht er schwimmen, zu Bekannten oder Karten spielen; zwischendurch jedoch, sobald sich eine freie Minute findet, öffnet er die Tür einer versteckten Zelle, stetzt sich rasch – und gleichsam zerstreut – vor ein schäbiges Instrument, schlägt einige Akkorde an und beginnt dann halblaut zu improvisieren, eine weitere von inzwischen zahllosen Variationen des seit Jahrzehnten gespielten, immer gleichen Themas. Kurz darauf springt er auf, muß gehendoch sobald sich wieder freie Zeit findet, sehen wir ihn abermals vor dem Instrument, als sei sein Leben nur die notgedrungene Unterbrechung zwischen zwei Spielen. Würden die Töne, die er dem Instrument entlockt, aufstehen und, gleichsam ineinander verdichtet, in der Luft gefrieren, würden wir vielleicht ein Eiskristallgebilde erblicken, an eine verkrampfte katatonische Bewegung erinnernd, worin, bei genauerer Betrachtung, zweifellos die Hartnäckigkeit einer Ausdrucksabsicht zu erkennen wäre, wenn auch nur die der Monotonie; setzten wir sie gar in Noten, könnten wir vermutlich die Umrisse einer sich mehr und mehr verdichtenden Fuge herauslösen, die immer entschlossener zu ihrem Ziel durchbricht, dabei aber dieses Ziel immer weiter fortschiebt, fortstößt von sich, und so wird es dennoch immer ungewisser. – Für wen spielt er? Warum spielt er? Er weiß es selbst nicht. Zudem – und das ist das Merkwürdigste daran – kann er nicht einmal hören, was er spielt. Als habe ihm die gespenstische Kraft, die ihn wieder und wieder an sein Instrument zwingt, das Gehör geraubt, damit er allein für sie spiele. – Ob jedoch sie ihn wenigstens hört? (Die Frage, sehen wir es ein, ist sinnlos, aber den Spieler müssen wir uns natürlich glücklich vorstellen.)

Schwamm, Kristin

![]()

FLEURSDUMAL.NL MAGAZINE

More in: Archive K-L, Kertész, Imre

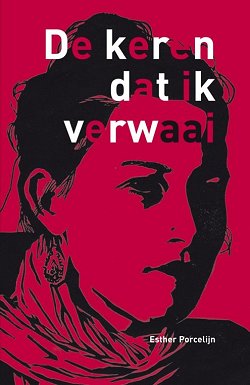

Esther Porcelijn

De superstorm

De keren dat ik verwaai

zijn gevaarlijk voor ons al.

Vluchten doet zelfs de kraai

op het dakje, opgeschrikt door vreemd geschal.

Weggedoken onder een stoel.

De krant vliegt in het rond,

mijn haren overeind bij het gevoel

dat ik dove woorden pers uit mijn mond.

Gegil verstomt bij elke schreeuw

van menig man die loopt op straat.

De kraai zoekt schutting bij een meeuw.

De weerman heeft geen paraplu paraat.

Als ik gedwongen word de oorsprong van dit noodweer op te sporen

kijk ik naast me, zie mijn vriendje, met benen opgetrokken, dromend

over chili-con-carne.

Esther Porcelijn gedicht

uit de nieuwe bundel: De keren dat ik verwaai

De keren dat ik verwaai is verkrijgbaar

of te bestellen via de reguliere boekhandel

of via uitgeverij teleXpress – www.telespress.nl

ISBN/EAN: 978-90-76937-44-1

Prijs: 15 euro

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive O-P, Art & Literature News, Porcelijn, Esther

Ton van Reen

DE GEVANGENE XVII

Nadat alle foto’s zo waren toegetakeld, had hij ze weggegooid. Hij zag dat een romp op de foto evenmin echt was. Een romp kon niet lachen tegen het halve gezicht van een meisje zonder borsten. De romp op andere foto’s kon onmogelijk een hoofd rechtop houden. Een romp kon nooit een pet op hebben gehad met de onderscheidingstekens van het zoveelste regiment artillerie waarbij Leo zoveel jaren had versleten. Wel zeven. Waarbij het ongeluk gebeurde met de granaat die bestemd was voor korporaal Waskop. De granaat die zo vrij was zijn benen te verbrijzelen in plaats van de gehele korporaal Waskop, die node gemist kon worden. Hij berekende onfeilbaar kogelbanen en was commandant van het zoveelste geschut. Nadat hij sergeant Tolsti was opgevolgd, die ze voor zijn raap hadden geschoten en die aan stukken was gereten. Door net zo’n granaat als die welke voor korporaal Waskop bestemd was geweest.

Ook de foto’s van andere mensen had Leo weggegooid. Die had hij ook tot rompen verknipt. Hij had willen weten hoe die anderen er zonder armen en benen uitzagen. Het had nergens op geleken. Hij kon zich onmogelijk voorstellen dat een romp op een paard zat waarvan de rug was verknipt en dan nog op een trompet blies ook. En dat rompen door straten gingen. Ze moesten zweven, benen hadden ze niet.

Hij haalde de pas uit zijn colbert, scheurde er de foto uit, hield hem aan een sigaret en brandde de ogen uit. Daarna de neus, mond en oren. De foto met brandgaten gooide hij in de vuilnisbak. Hij dacht er plots aan dat hij moest huilen. In deze tijd kon het niet bestaan dat je gezicht nergens geregistreerd was op lichtecht fotopapier.

Huilen had hij afgeleerd. Hij was blij dat hij met zijn hand de laatste resten van de behangachtige foto van de muur kon strijken. Een van de blote kinderbenen met de halve pijp van een matrozenbroek bleef op zijn arm liggen. Hij blies de schilfers weg. Daarna kon hij het beeld van een kinderbeen niet meer weg krijgen, het laatste wat hij van zichzelf op een foto had gezien.

Aan de muur was nu een grijze vlek meer. Slijm borrelde uit de vlek. Zat er een krater in de muur? Er moest een riool kapot zijn. Waar zou anders die vuile etter vandaan komen?

Ter gelegenheid van de twintigste verjaardag die Leo achter de ruit vierde, was de processie door de Libertystraat gekomen. De processie liep niet. Ze gleed. Als een beest dat zich schrap zette tegen de straatstenen: kinderkopjes die gekapt waren uit grote blokken natuursteen.

Vooraan in de processie liepen kinderen die hoofdjes hadden, even stenig als de kinderkopjes waarover ze de straat in en uit liepen. Netjes in één richting gaande. Het kon zijn dat er achter hen een ongelikte beer volgde.

Dat was ook zo. Achter hen liep pastoor Kruppa in een jurk die een uniform was. Een toog uit zwarte zijde die een huilerig en ongebruikt geslacht verborg. Onder een doek droeg deze Kruppa iets wat niet zichtbaar was. Toch zichtbaar hoorde te zijn.

Kruppa was een priester uit de kerk van de parochie van de Heilige Moeder Gods. Hij liep nu met het Zoontje van die Moeder in zijn armen, hield het beschermend onder een doek zodat het Zoontje Gods niet de Libertystraat zou zien. Niet Leo achter het glas. Niet meneer Pesche, die juist de straat uit liep om te gaan eten in restaurant Varsgarten. Noch de asman die met zijn vuile achterwerk op het schone vuilnisvat van de familie F. zat. Noch de man zonder rechterarm in zijn groen schijnende huis. Ook zou het Kind van de Moeder Gods niet vermoeden dat in haar kamer het meisje achter het glas stond te kijken.

(wordt vervolgd)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - De gevangene

MARTIN BEVERSLUIS

Tijdbom

Woorden zijn gordijnen die je toedoet

zodra het spektakel is afgelopen het

waren mooie beelden een stuk of acht

jongens die in het midden van de nacht

iemand aanvielen en helemaal verrot

schopten na de daden komen dan altijd

de woorden die van afschuw het eerst

dan is het gevaar geweken kunnen we

de toedracht gaan verklaren deze tijden

zijn van teruggang en onbegrip dat vatten

we onvermijdelijk persoonlijk op hoe kan

dit mij overkomen een frustratio die er

toe doet die smeekt om een uitlaatklep

het grote verklaren is begonnen na ieder

conflict begrijpen we meer tot begrip ook

niet meer helpt en het recht van de sterkste

geldt deze woorden zijn gordijnen die

je dicht doet als je het denkraam sluit

een tijdbom wordt terloops ontploft.

Martin Beversluis poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Beversluis, Martin

William Butler Yeats

(1865 – 1939)

The Heart of the Woman

O what to me the little room

That was brimmed up with prayer and rest;

He bade me out into the gloom,

And my breast lies upon his breast.

O what to me my mother’s care,

The house where I was safe and warm;

The shadowy blossom of my hair

Will hide us from the bitter storm.

O hiding hair and dewy eyes,

I am no more with life and death,

My heart upon his warm heart lies,

My breath is mixed into his breath.

William Butler Yeats poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive Y-Z, Yeats, William Butler

James Joyce

(1882-1941)

A Little Cloud

Eight years before he had seen his friend off at the North Wall and wished him godspeed. Gallaher had got on. You could tell that at once by his travelled air, his well-cut tweed suit, and fearless accent. Few fellows had talents like his and fewer still could remain unspoiled by such success. Gallaher’s heart was in the right place and he had deserved to win. It was something to have a friend like that.

Little Chandler’s thoughts ever since lunch-time had been of his meeting with Gallaher, of Gallaher’s invitation and of the great city London where Gallaher lived. He was called Little Chandler because, though he was but slightly under the average stature, he gave one the idea of being a little man. His hands were white and small, his frame was fragile, his voice was quiet and his manners were refined. He took the greatest care of his fair silken hair and moustache and used perfume discreetly on his handkerchief. The half-moons of his nails were perfect and when he smiled you caught a glimpse of a row of childish white teeth.

As he sat at his desk in the King’s Inns he thought what changes those eight years had brought. The friend whom he had known under a shabby and necessitous guise had become a brilliant figure on the London Press. He turned often from his tiresome writing to gaze out of the office window. The glow of a late autumn sunset covered the grass plots and walks. It cast a shower of kindly golden dust on the untidy nurses and decrepit old men who drowsed on the benches; it flickered upon all the moving figures, on the children who ran screaming along the gravel paths and on everyone who passed through the gardens. He watched the scene and thought of life; and (as always happened when he thought of life) he became sad. A gentle melancholy took possession of him. He felt how useless it was to struggle against fortune, this being the burden of wisdom which the ages had bequeathed to him.

He remembered the books of poetry upon his shelves at home. He had bought them in his bachelor days and many an evening, as he sat in the little room off the hall, he had been tempted to take one down from the bookshelf and read out something to his wife. But shyness had always held him back; and so the books had remained on their shelves. At times he repeated lines to himself and this consoled him.

When his hour had struck he stood up and took leave of his desk and of his fellow-clerks punctiliously. He emerged from under the feudal arch of the King’s Inns, a neat modest figure, and walked swiftly down Henrietta Street. The golden sunset was waning and the air had grown sharp. A horde of grimy children populated the street. They stood or ran in the roadway or crawled up the steps before the gaping doors or squatted like mice upon the thresholds. Little Chandler gave them no thought. He picked his way deftly through all that minute vermin-like life and under the shadow of the gaunt spectral mansions in which the old nobility of Dublin had roystered. No memory of the past touched him, for his mind was full of a present joy.

He had never been in Corless’s but he knew the value of the name. He knew that people went there after the theatre to eat oysters and drink liqueurs; and he had heard that the waiters there spoke French and German. Walking swiftly by at night he had seen cabs drawn up before the door and richly dressed ladies, escorted by cavaliers, alight and enter quickly. They wore noisy dresses and many wraps. Their faces were powdered and they caught up their dresses, when they touched earth, like alarmed Atalantas. He had always passed without turning his head to look. It was his habit to walk swiftly in the street even by day and whenever he found himself in the city late at night he hurried on his way apprehensively and excitedly. Sometimes, however, he courted the causes of his fear. He chose the darkest and narrowest streets and, as he walked boldly forward, the silence that was spread about his footsteps troubled him, the wandering, silent figures troubled him; and at times a sound of low fugitive laughter made him tremble like a leaf.

He turned to the right towards Capel Street. Ignatius Gallaher on the London Press! Who would have thought it possible eight years before? Still, now that he reviewed the past, Little Chandler could remember many signs of future greatness in his friend. People used to say that Ignatius Gallaher was wild Of course, he did mix with a rakish set of fellows at that time. drank freely and borrowed money on all sides. In the end he had got mixed up in some shady affair, some money transaction: at least, that was one version of his flight. But nobody denied him talent. There was always a certain . . . something in Ignatius Gallaher that impressed you in spite of yourself. Even when he was out at elbows and at his wits’ end for money he kept up a bold face. Little Chandler remembered (and the remembrance brought a slight flush of pride to his cheek) one of Ignatius Gallaher’s sayings when he was in a tight corner

“Half time now, boys,” he used to say light-heartedly. “Where’s my considering cap?”

That was Ignatius Gallaher all out; and, damn it, you couldn’t but admire him for it.

Little Chandler quickened his pace. For the first time in his life he felt himself superior to the people he passed. For the first time his soul revolted against the dull inelegance of Capel Street. There was no doubt about it: if you wanted to succeed you had to go away. You could do nothing in Dublin. As he crossed Grattan Bridge he looked down the river towards the lower quays and pitied the poor stunted houses. They seemed to him a band of tramps, huddled together along the riverbanks, their old coats covered with dust and soot, stupefied by the panorama of sunset and waiting for the first chill of night bid them arise, shake themselves and begone. He wondered whether he could write a poem to express his idea. Perhaps Gallaher might be able to get it into some London paper for him. Could he write something original? He was not sure what idea he wished to express but the thought that a poetic moment had touched him took life within him like an infant hope. He stepped onward bravely.

Every step brought him nearer to London, farther from his own sober inartistic life. A light began to tremble on the horizon of his mind. He was not so old, thirty-two. His temperament might be said to be just at the point of maturity. There were so many different moods and impressions that he wished to express in verse. He felt them within him. He tried weigh his soul to see if it was a poet’s soul. Melancholy was the dominant note of his temperament, he thought, but it was a melancholy tempered by recurrences of faith and resignation and simple joy. If he could give expression to it in a book of poems perhaps men would listen. He would never be popular: he saw that. He could not sway the crowd but he might appeal to a little circle of kindred minds. The English critics, perhaps, would recognise him as one of the Celtic school by reason of the melancholy tone of his poems; besides that, he would put in allusions. He began to invent sentences and phrases from the notice which his book would get. “Mr. Chandler has the gift of easy and graceful verse.” . . . “wistful sadness pervades these poems.” . . . “The Celtic note.” It was a pity his name was not more Irish-looking. Perhaps it would be better to insert his mother’s name before the surname: Thomas Malone Chandler, or better still: T. Malone Chandler. He would speak to Gallaher about it.

He pursued his revery so ardently that he passed his street and had to turn back. As he came near Corless’s his former agitation began to overmaster him and he halted before the door in indecision. Finally he opened the door and entered.

The light and noise of the bar held him at the doorways for a few moments. He looked about him, but his sight was confused by the shining of many red and green wine-glasses The bar seemed to him to be full of people and he felt that the people were observing him curiously. He glanced quickly to right and left (frowning slightly to make his errand appear serious), but when his sight cleared a little he saw that nobody had turned to look at him: and there, sure enough, was Ignatius Gallaher leaning with his back against the counter and his feet planted far apart.

“Hallo, Tommy, old hero, here you are! What is it to be? What will you have? I’m taking whisky: better stuff than we get across the water. Soda? Lithia? No mineral? I’m the same Spoils the flavour. . . . Here, garçon, bring us two halves of malt whisky, like a good fellow. . . . Well, and how have you been pulling along since I saw you last? Dear God, how old we’re getting! Do you see any signs of aging in me, eh, what? A little grey and thin on the top, what?”

Ignatius Gallaher took off his hat and displayed a large closely cropped head. His face was heavy, pale and cleanshaven. His eyes, which were of bluish slate-colour, relieved his unhealthy pallor and shone out plainly above the vivid orange tie he wore. Between these rival features the lips appeared very long and shapeless and colourless. He bent his head and felt with two sympathetic fingers the thin hair at the crown. Little Chandler shook his head as a denial. Ignatius Galaher put on his hat again.

“It pulls you down,” be said, “Press life. Always hurry and scurry, looking for copy and sometimes not finding it: and then, always to have something new in your stuff. Damn proofs and printers, I say, for a few days. I’m deuced glad, I can tell you, to get back to the old country. Does a fellow good, a bit of a holiday. I feel a ton better since I landed again in dear dirty Dublin. . . . Here you are, Tommy. Water? Say when.”

Little Chandler allowed his whisky to be very much diluted.

“You don’t know what’s good for you, my boy,” said Ignatius Gallaher. “I drink mine neat.”

“I drink very little as a rule,” said Little Chandler modestly. “An odd half-one or so when I meet any of the old crowd: that’s all.”

“Ah well,” said Ignatius Gallaher, cheerfully, “here’s to us and to old times and old acquaintance.”

They clinked glasses and drank the toast.

“I met some of the old gang today,” said Ignatius Gallaher. “O’Hara seems to be in a bad way. What’s he doing?”

“Nothing,” said Little Chandler. “He’s gone to the dogs.”

“But Hogan has a good sit, hasn’t he?”

“Yes; he’s in the Land Commission.”

“I met him one night in London and he seemed to be very flush. . . . Poor O’Hara! Boose, I suppose?”

“Other things, too,” said Little Chandler shortly.

Ignatius Gallaher laughed.

“Tommy,” he said, “I see you haven’t changed an atom. You’re the very same serious person that used to lecture me on Sunday mornings when I had a sore head and a fur on my tongue. You’d want to knock about a bit in the world. Have you never been anywhere even for a trip?”

“I’ve been to the Isle of Man,” said Little Chandler.

Ignatius Gallaher laughed.

“The Isle of Man!” he said. “Go to London or Paris: Paris, for choice. That’d do you good.”

“Have you seen Paris?”

“I should think I have! I’ve knocked about there a little.”

“And is it really so beautiful as they say?” asked Little Chandler.

He sipped a little of his drink while Ignatius Gallaher finished his boldly.

“Beautiful?” said Ignatius Gallaher, pausing on the word and on the flavour of his drink. “It’s not so beautiful, you know. Of course, it is beautiful. . . . But it’s the life of Paris; that’s the thing. Ah, there’s no city like Paris for gaiety, movement, excitement. . . . ”

Little Chandler finished his whisky and, after some trouble, succeeded in catching the barman’s eye. He ordered the same again.

“I’ve been to the Moulin Rouge,” Ignatius Gallaher continued when the barman had removed their glasses, “and I’ve been to all the Bohemian cafes. Hot stuff! Not for a pious chap like you, Tommy.”

Little Chandler said nothing until the barman returned with two glasses: then he touched his friend’s glass lightly and reciprocated the former toast. He was beginning to feel somewhat disillusioned. Gallaher’s accent and way of expressing himself did not please him. There was something vulgar in his friend which he had not observed before. But perhaps it was only the result of living in London amid the bustle and competition of the Press. The old personal charm was still there under this new gaudy manner. And, after all, Gallaher had lived, he had seen the world. Little Chandler looked at his friend enviously.

“Everything in Paris is gay,” said Ignatius Gallaher. “They believe in enjoying life, and don’t you think they’re right? If you want to enjoy yourself properly you must go to Paris. And, mind you, they’ve a great feeling for the Irish there. When they heard I was from Ireland they were ready to eat me, man.”

Little Chandler took four or five sips from his glass.

“Tell me,” he said, “is it true that Paris is so . . . immoral as they say?”

Ignatius Gallaher made a catholic gesture with his right arm.

“Every place is immoral,” he said. “Of course you do find spicy bits in Paris. Go to one of the students’ balls, for instance. That’s lively, if you like, when the cocottes begin to let themselves loose. You know what they are, I suppose?”

“I’ve heard of them,” said Little Chandler.

Ignatius Gallaher drank off his whisky and shook his had.

“Ah,” he said, “you may say what you like. There’s no woman like the Parisienne, for style, for go.”

“Then it is an immoral city,” said Little Chandler, with timid insistence, “I mean, compared with London or Dublin?”

“London!” said Ignatius Gallaher. “It’s six of one and half-a-dozen of the other. You ask Hogan, my boy. I showed him a bit about London when he was over there. He’d open your eye. . . . I say, Tommy, don’t make punch of that whisky: liquor up.”

“No, really. . . . ”

“O, come on, another one won’t do you any harm. What is it? The same again, I suppose?”

“Well . . . all right.”

“François, the same again. . . . Will you smoke, Tommy?”

Ignatius Gallaher produced his cigar-case. The two friends lit their cigars and puffed at them in silence until their drinks were served.

“I’ll tell you my opinion,” said Ignatius Gallaher, emerging after some time from the clouds of smoke in which he had taken refuge, “it’s a rum world. Talk of immorality! I’ve heard of cases, what am I saying?, I’ve known them: cases of . . . immorality. . . . ”

Ignatius Gallaher puffed thoughtfully at his cigar and then, in a calm historian’s tone, he proceeded to sketch for his friend some pictures of the corruption which was rife abroad. He summarised the vices of many capitals and seemed inclined to award the palm to Berlin. Some things he could not vouch for (his friends had told him), but of others he had had personal experience. He spared neither rank nor caste. He revealed many of the secrets of religious houses on the Continent and described some of the practices which were fashionable in high society and ended by telling, with details, a story about an English duchess, a story which he knew to be true. Little Chandler as astonished.

“Ah, well,” said Ignatius Gallaher, “here we are in old jog-along Dublin where nothing is known of such things.”

“How dull you must find it,” said Little Chandler, “after all the other places you’ve seen!”

Well,” said Ignatius Gallaher, “it’s a relaxation to come over here, you know. And, after all, it’s the old country, as they say, isn’t it? You can’t help having a certain feeling for it. That’s human nature. . . . But tell me something about yourself. Hogan told me you had . . . tasted the joys of connubial bliss. Two years ago, wasn’t it?”

Little Chandler blushed and smiled.

“Yes,” he said. “I was married last May twelve months.”

“I hope it’s not too late in the day to offer my best wishes,” said Ignatius Gallaher. “I didn’t know your address or I’d have done so at the time.”

He extended his hand, which Little Chandler took.

“Well, Tommy,” he said, “I wish you and yours every joy in life, old chap, and tons of money, and may you never die till I shoot you. And that’s the wish of a sincere friend, an old friend. You know that?”

“I know that,” said Little Chandler.

“Any youngsters?” said Ignatius Gallaher.

Little Chandler blushed again.

“We have one child,” he said.

“Son or daughter?”

“A little boy.”

Ignatius Gallaher slapped his friend sonorously on the back.

“Bravo,” he said, “I wouldn’t doubt you, Tommy.”

Little Chandler smiled, looked confusedly at his glass and bit his lower lip with three childishly white front teeth.

“I hope you’ll spend an evening with us,” he said, “before you go back. My wife will be delighted to meet you. We can have a little music and, , ”

“Thanks awfully, old chap,” said Ignatius Gallaher, “I’m sorry we didn’t meet earlier. But I must leave tomorrow night.”

“Tonight, perhaps . . . ?”

“I’m awfully sorry, old man. You see I’m over here with another fellow, clever young chap he is too, and we arranged to go to a little card-party. Only for that . . . ”

“O, in that case . . . ”

“But who knows?” said Ignatius Gallaher considerately. “Next year I may take a little skip over here now that I’ve broken the ice. It’s only a pleasure deferred.”

“Very well,” said Little Chandler, “the next time you come we must have an evening together. That’s agreed now, isn’t it?”

“Yes, that’s agreed,” said Ignatius Gallaher. “Next year if I come, parole d’honneur.”

“And to clinch the bargain,” said Little Chandler, “we’ll just have one more now.”

Ignatius Gallaher took out a large gold watch and looked a it.

“Is it to be the last?” he said. “Because you know, I have an a.p.”

“O, yes, positively,” said Little Chandler.

“Very well, then,” said Ignatius Gallaher, “let us have another one as a deoc an doruis, that’s good vernacular for a small whisky, I believe.”

Little Chandler ordered the drinks. The blush which had risen to his face a few moments before was establishing itself. A trifle made him blush at any time: and now he felt warm and excited. Three small whiskies had gone to his head and Gallaher’s strong cigar had confused his mind, for he was a delicate and abstinent person. The adventure of meeting Gallaher after eight years, of finding himself with Gallaher in Corless’s surrounded by lights and noise, of listening to Gallaher’s stories and of sharing for a brief space Gallaher’s vagrant and triumphant life, upset the equipoise of his sensitive nature. He felt acutely the contrast between his own life and his friend’s and it seemed to him unjust. Gallaher was his inferior in birth and education. He was sure that he could do something better than his friend had ever done, or could ever do, something higher than mere tawdry journalism if he only got the chance. What was it that stood in his way? His unfortunate timidity He wished to vindicate himself in some way, to assert his manhood. He saw behind Gallaher’s refusal of his invitation. Gallaher was only patronising him by his friendliness just as he was patronising Ireland by his visit.

The barman brought their drinks. Little Chandler pushed one glass towards his friend and took up the other boldly.

“Who knows?” he said, as they lifted their glasses. “When you come next year I may have the pleasure of wishing long life and happiness to Mr. and Mrs. Ignatius Gallaher.”

Ignatius Gallaher in the act of drinking closed one eye expressively over the rim of his glass. When he had drunk he smacked his lips decisively, set down his glass and said:

“No blooming fear of that, my boy. I’m going to have my fling first and see a bit of life and the world before I put my head in the sack, if I ever do.”

“Some day you will,” said Little Chandler calmly.

Ignatius Gallaher turned his orange tie and slate-blue eyes full upon his friend.

“You think so?” he said.

“You’ll put your head in the sack,” repeated Little Chandler stoutly, “like everyone else if you can find the girl.”

He had slightly emphasised his tone and he was aware that he had betrayed himself; but, though the colour had heightened in his cheek, he did not flinch from his friend’s gaze. Ignatius Gallaher watched him for a few moments and then said:

“If ever it occurs, you may bet your bottom dollar there’ll be no mooning and spooning about it. I mean to marry money. She’ll have a good fat account at the bank or she won’t do for me.”

Little Chandler shook his head.

“Why, man alive,” said Ignatius Gallaher, vehemently, “do you know what it is? I’ve only to say the word and tomorrow I can have the woman and the cash. You don’t believe it? Well, I know it. There are hundreds, what am I saying?, thousands of rich Germans and Jews, rotten with money, that’d only be too glad. . . . You wait a while my boy. See if I don’t play my cards properly. When I go about a thing I mean business, I tell you. You just wait.”

He tossed his glass to his mouth, finished his drink and laughed loudly. Then he looked thoughtfully before him and said in a calmer tone:

“But I’m in no hurry. They can wait. I don’t fancy tying myself up to one woman, you know.”

He imitated with his mouth the act of tasting and made a wry face.

“Must get a bit stale, I should think,” he said.

Little Chandler sat in the room off the hall, holding a child in his arms. To save money they kept no servant but Annie’s young sister Monica came for an hour or so in the morning and an hour or so in the evening to help. But Monica had gone home long ago. It was a quarter to nine. Little Chandler had come home late for tea and, moreover, he had forgotten to bring Annie home the parcel of coffee from Bewley’s. Of course she was in a bad humour and gave him short answers. She said she would do without any tea but when it came near the time at which the shop at the corner closed she decided to go out herself for a quarter of a pound of tea and two pounds of sugar. She put the sleeping child deftly in his arms and said:

“Here. Don’t waken him.”

A little lamp with a white china shade stood upon the table and its light fell over a photograph which was enclosed in a frame of crumpled horn. It was Annie’s photograph. Little Chandler looked at it, pausing at the thin tight lips. She wore the pale blue summer blouse which he had brought her home as a present one Saturday. It had cost him ten and elevenpence; but what an agony of nervousness it had cost him! How he had suffered that day, waiting at the shop door until the shop was empty, standing at the counter and trying to appear at his ease while the girl piled ladies’ blouses before him, paying at the desk and forgetting to take up the odd penny of his change, being called back by the cashier, and finally, striving to hide his blushes as he left the shop by examining the parcel to see if it was securely tied. When he brought the blouse home Annie kissed him and said it was very pretty and stylish; but when she heard the price she threw the blouse on the table and said it was a regular swindle to charge ten and elevenpence for it. At first she wanted to take it back but when she tried it on she was delighted with it, especially with the make of the sleeves, and kissed him and said he was very good to think of her.

Hm! . . .

He looked coldly into the eyes of the photograph and they answered coldly. Certainly they were pretty and the face itself was pretty. But he found something mean in it. Why was it so unconscious and ladylike? The composure of the eyes irritated him. They repelled him and defied him: there was no passion in them, no rapture. He thought of what Gallaher had said about rich Jewesses. Those dark Oriental eyes, he thought, how full they are of passion, of voluptuous longing! . . . Why had he married the eyes in the photograph?

He caught himself up at the question and glanced nervously round the room. He found something mean in the pretty furniture which he had bought for his house on the hire system. Annie had chosen it herself and it reminded him of her. It too was prim and pretty. A dull resentment against his life awoke within him. Could he not escape from his little house? Was it too late for him to try to live bravely like Gallaher? Could he go to London? There was the furniture still to be paid for. If he could only write a book and get it published, that might open the way for him.

A volume of Byron’s poems lay before him on the table. He opened it cautiously with his left hand lest he should waken the child and began to read the first poem in the book:

Hushed are the winds and still the evening gloom,

Not e’en a Zephyr wanders through the grove,

Whilst I return to view my Margaret’s tomb

And scatter flowers on the dust I love.

He paused. He felt the rhythm of the verse about him in the room. How melancholy it was! Could he, too, write like that, express the melancholy of his soul in verse? There were so many things he wanted to describe: his sensation of a few hours before on Grattan Bridge, for example. If he could get back again into that mood. . . .

The child awoke and began to cry. He turned from the page and tried to hush it: but it would not be hushed. He began to rock it to and fro in his arms but its wailing cry grew keener. He rocked it faster while his eyes began to read the second stanza:

Within this narrow cell reclines her clay,

That clay where once . . .

It was useless. He couldn’t read. He couldn’t do anything. The wailing of the child pierced the drum of his ear. It was useless, useless! He was a prisoner for life. His arms trembled with anger and suddenly bending to the child’s face he shouted:

“Stop!”

The child stopped for an instant, had a spasm of fright and began to scream. He jumped up from his chair and walked hastily up and down the room with the child in his arms. It began to sob piteously, losing its breath for four or five seconds, and then bursting out anew. The thin walls of the room echoed the sound. He tried to soothe it but it sobbed more convulsively. He looked at the contracted and quivering face of the child and began to be alarmed. He counted seven sobs without a break between them and caught the child to his breast in fright. If it died! . . .

The door was burst open and a young woman ran in, panting.

“What is it? What is it?” she cried.

The child, hearing its mother’s voice, broke out into a paroxysm of sobbing.

“It’s nothing, Annie . . . it’s nothing. . . . He began to cry . . . ”

She flung her parcels on the floor and snatched the child from him.

“What have you done to him?” she cried, glaring into his face.

Little Chandler sustained for one moment the gaze of her eyes and his heart closed together as he met the hatred in them. He began to stammer:

“It’s nothing. . . . He . . . he began to cry. . . . I couldn’t . . . I didn’t do anything. . . . What?”

Giving no heed to him she began to walk up and down the room, clasping the child tightly in her arms and murmuring:

“My little man! My little mannie! Was ’ou frightened, love? . . . There now, love! There now!… Lambabaun! Mamma’s little lamb of the world! . . . There now!”

Little Chandler felt his cheeks suffused with shame and he stood back out of the lamplight. He listened while the paroxysm of the child’s sobbing grew less and less; and tears of remorse started to his eyes.

James Joyce stories

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive I-J, Joyce, James, Joyce, James

Giacomo Leopardi

(1798-1837)

A Silvia

Silvia, rimembri ancora

Quel tempo della tua vita mortale,

Quando beltà splendea

Negli occhi tuoi ridenti e fuggitivi,

E tu, lieta e pensosa, il limitare

Di gioventù salivi?

Sonavan le quiete

Stanze, e le vie dintorno,

Al tuo perpetuo canto,

Allor che all’opre femminili intenta

Sedevi, assai contenta

Di quel vago avvenir che in mente avevi.

Era il maggio odoroso: e tu solevi

Così menare il giorno.

Io gli studi leggiadri

Talor lasciando e le sudate carte,

Ove il tempo mio primo

E di me si spendea la miglior parte,

D’in su i veroni del paterno ostello

Porgea gli orecchi al suon della tua voce,

Ed alla man veloce

Che percorrea la faticosa tela.

Mirava il ciel sereno,

Le vie dorate e gli orti,

E quinci il mar da lungi, e quindi il monte.

Lingua mortal non dice

Quel ch’io sentiva in seno.

Che pensieri soavi,

Che speranze, che cori, o Silvia mia!

Quale allor ci apparia

La vita umana e il fato!

Quando sovviemmi di cotanta speme,

Un affetto mi preme

Acerbo e sconsolato,

E tornami a doler di mia sventura.

O natura, o natura,

Perchè non rendi poi

Quel che prometti allor? perchè di tanto

Inganni i figli tuoi?

Tu pria che l’erbe inaridisse il verno,

Da chiuso morbo combattuta e vinta,

Perivi, o tenerella. E non vedevi

Il fior degli anni tuoi;

Non ti molceva il core

La dolce lode or delle negre chiome,

Or degli sguardi innamorati e schivi;

Nè teco le compagne ai dì festivi

Ragionavan d’amore.

Anche peria fra poco

La speranza mia dolce: agli anni miei

Anche negaro i fati

La giovanezza. Ahi come,

Come passata sei,

Cara compagna dell’età mia nova,

Mia lacrimata speme!

Questo è quel mondo? questi

I diletti, l’amor, l’opre, gli eventi

Onde cotanto ragionammo insieme?

Questa la sorte dell’umane genti?

All’apparir del vero

Tu, misera, cadesti: e con la mano

La fredda morte ed una tomba ignuda

Mostravi di lontano.

![]()

Giacomo Leopardi poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive K-L, Leopardi, Giacomo

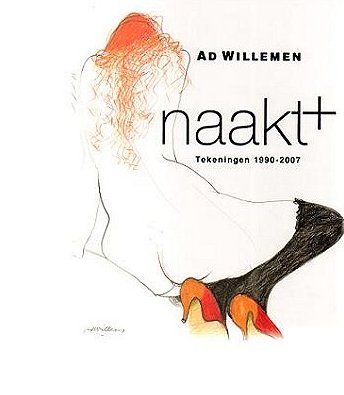

I n M e m o r i a m A d W i l l e m e n

Jasper Mikkers

Teruggebracht Vuur (1)(2)

alle beelden zijn tot rust gekomen

het sneeuwt niet meer, niet in het hoofd, niet achter vensterglas

persen, lijsten, kasten, stiften en penselen

het water in de leiding: alles houdt zich stil

het ontbreekt de wil te zijn nu hij er niet meer is

door de verwildering van vlees is wie hij was

vermenigvuldigd tot een handvol gras

alle beelden zijn tot rust gekomen

de boeren die naar huis toe liepen na het planten van de rijst

de spelerstroep, halfweg een touwbrug over een ravijn

de vlokken die nog vielen, hangen roerloos in de lucht

nu hij is gestopt met dromen

geen naakt zijn netvlies raakt

schoonheid vond hier zwart en rood

geen wit van borsten, bil en dij wordt nog gevangen

in gebogen lijnen: wie stopt nu het verdwijnen

het verdrogen van de jonge vormen in de tijd, wie houdt

het woelen van verlangen ons voor ogen, legt

eeuwig voelen vast

een vuur teruggebracht tot minder dan miniatuur

geen tijd stroomt door zijn vlees, beweegt zijn hand

zijn stem heeft zich verzacht tot minder nog dan hees

zijn bril, een venster dat vergrootte wat zich aan het oog

onttrekken wou, een omgestoten whiskyfles en tekenblok

liggen op tafel, naast zijn broeksriem en een sok

(1) Dit gedicht schreef ik in mijn functie van stadsdichter.

(2) Op 24 september is kunstenaar Ad Willemen overleden. Hij was tekenaar, etser, lithograaf en fotograaf en maakte gouaches. Hij was de leermeester van Reinoud van Vugt en Marc Mulders, exposeerde in binnen- en buitenland en won prijzen. Hij gaf les aan het Koning Willem II College. Met zijn miniaturen van klassieke schilderijen en naakttekeningen (Het geheime oeuvre van Adriaan Willemen) verwierf hij een grote bekendheid.

Jasper Mikkers is stadsdichter van Tilburg

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Ad Willemen, Archive M-N, In Memoriam, Mikkers, Jasper

Kunstenaar Ad Willemen overleden

De Tilburgse kunstenaar Ad Willemen is maandagavond (23 september 2013) overleden. Eind vorig jaar werd bekend dat bij Willemen een hersentumor was vastgesteld.

Ad Willemen was internationaal vermaard om zijn grafisch werk, waarvoor hij vele prijzen ontving. In het werk van Ad Willemen stond het vrouwelijk naakt centraal. Willemen was lange tijd docent aan de kunstacdemie St. Joost in Breda. Bekende kunstenaars zoal Marc Mulders en Reinoud van Vught behoorden tot zijn leerlingen.

Ad Willemen (A.C.J.M.) 6 april 1941 – 23 september 2013

Education

A.B.B.K. Tilburg, NL (1957 – 1961)

Academy St. Joost, Breda, NL (1962-1963)

Profession

Drawing, painting and graphic artist

Part time drawingmaster at the Academy St. Joost, Breda, Netherlands

Parttime drawingmaster Willem II-college, Tilburg, Netherlands

Prizes

Biennale-prize, Fredrikstad, Noorwegen, 1986

First prize G.S.E. 25, Eindhoven (NL), 1989

Jury-prize, Fredrikstad, Noorwegen, 1999

Honourable mention: Europese biennale voor Grafische Kunsten, Brugge, 2000

Museums

Museum Scryption Tilburg, NL

Museum Boymans van Beuningen, Rotterdam, NL

Amsterdam Museum, Amsterdam, Nl

Museum for Samtid Grafikk, Fredrikstad, Norway

Kanagawa Prefectural Gallery, Yokohama, Japan

Noordbrabants Museum, ’s Hertogenbosch, Nl

# meer informatie is te vinden op de website van Ad Willemen

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Ad Willemen, Art & Literature News, FDM Art Gallery, In Memoriam

Ton van Reen

DE GEVANGENE XVI

En in de oorlog had gediend bij het zoveelste regiment artillerie om er zijn benen te verliezen. Die nu verliefd zat te worden omdat hij geen rok naast zich kon zien.

Het meisje zou een sprookje dromen. Dat ze in de hemel woonde bij de Moeder Gods of zo. Misschien droomde ze van kinderen die ze zelf zou willen maken uit klei. Dan pas wilde ze hen baren. Ze zouden geen benen hebben en alleen maar een linkerarm.

Aan de muur hing een foto. Als Leo ernaar keek, moest hij, of hij wilde of niet, erg lachen. Het kind op de foto was hij zelf. De spijker waaraan de foto hing, werd weggevreten door slakkenslijm dat geen slakkenslijm was maar daar toch veel op leek. Het papier groeide vast aan de muur. Het werd een stuk behang. Als hij er met zijn nagel langs streek, raakten schilfertjes van het lichtende fotopapier los, vielen in stukjes matrozenjas en kinderwang op de vloer. Foto’s hielden niet op de muur.

Het was dom foto’s te bewaren. Elk jaar werd je anders. Aan je gezicht kon je niets veranderen. Je kon het nooit de vorm geven die het op een foto van vroeger had. Bovendien loog de foto niet. Er waren foto’s die logen als de ziekte, gezichten lieten zien die nooit bestaan hadden. Er waren altijd mensen die zeiden: `Kijk, dat is mijn gezicht.’ Dan waren ze trots op een gezicht dat van niemand was. Alleen gelogen werd door het fotopapier dat niet altijd even lichtecht was als wel werd beweerd.

Hij had nog één foto van zichzelf. Die zat vastgeniet in een vakje in zijn pas, die allang verlopen was. Hij droeg de pas toch altijd bij zich. Als legitimatiebewijs. Je kon nooit weten voor wie hij zich in zijn eigen huis zou moeten legitimeren.

Die pasfoto was ook gelogen. Volgens die foto had hij een grijs gezicht, grijze ogen, grijze haren en een grijze glimlach. Zijn haren hadden blond moeten zijn. Zijn huid rood. Hij had zich altijd geschaamd als hij een foto liet maken. Alsof het maken van een foto ijdelheid was. En zijn ogen waren grimmig geweest, op het katachtige af. Een glimlach om zijn mond had hij nooit gehad. Dat het leek of zijn sporthemd, vlinderdasje en colbert grijs waren, interesseerde hem niet.

Hij vroeg zich af waarom mensen kleur konden weglaten in foto’s, zodat die alleen maar grijs waren. Zelfs wit was nog niet eens behoorlijk wit. Er waren mensen die erin getraind waren om in alle tinten grijs kleuren te zien.

De rest van de foto’s van vroeger had hij niet meer. Nadat zijn benen waren weggeschoten, had hij uit alle foto’s zijn benen weggeknipt. Later ook de armen. Hij had het toen beter gevonden alleen romp te zijn. Met de armen had hij ook grote stukken weggeknipt uit de mensen die bij hem in de buurt waren geweest op het moment dat een foto van hem was genomen. Mensen die wetend of niet het lichtechte papier met hem deelden. Soms had hij die mensen vastgehouden. Zo had hij een foto waarop hij samen met een meisje stond. Ze hadden gelachen tegen het vogeltje van de fotograaf. Toen hij benen en armen uit de foto knipte, had hij haar borsten en de linkerhelft van haar gezicht geamputeerd. Zijn ene arm had over haar borsten gelegen, met de hand van de andere arm hield hij haar gezicht voor de helft bedekt. Hij had haar stevig vastgehouden.

(wordt vervolgd)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - De gevangene

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature