Fleurs du Mal Magazine

Oscar Wilde

Oscar Wilde

(1854 – 1900)

The House of Judgement

And there was silence in the House of Judgment, and the Man came naked before God.

And God opened the Book of the Life of the Man.

And God said to the Man, ‘Thy life hath been evil, and thou hast shown cruelty to those who were in need of succour, and to those who lacked help thou hast been bitter and hard of heart. The poor called to thee and thou didst not hearken, and thine ears were closed to the cry of My afflicted. The inheritance of the fatherless thou didst take unto thyself and thou didst send the foxes into the vineyard of thy neighbour’s field. Thou didst take the bread of the children and give it to the dogs to eat, and My lepers who lived in the marshes, and were at peace and praised Me, thou didst drive forth on to the highways, and on Mine earth out of which I made thee thou didst spill innocent blood.’

And the Man made answer and said, ‘Even so did I.’

And again God opened the Book of the Life of the Man.

And God said to the Man, ‘Thy life hath been evil, and the Beauty I have shown thou hast sought for, and the Good I have hidden thou didst pass by. The walls of thy chamber were painted with images, and from the bed of thine abominations thou didst rise up to the sound of flutes. Thou didst build seven altars to the sins I have suffered, and didst eat of the thing that may not be eaten, and the purple of thy raiment was broidered with the three signs of shame. Thine idols were neither of gold nor of silver that endure, but of flesh that dieth. Thou didst stain their hair with perfumes and put pomegranates in their hands. Thou didst stain their feet with saffron and spread carpets before them. With antimony thou didst stain their eyelids and their bodies thou didst smear with myrrh. Thou didst bow thyself to the ground before them, and the thrones of thine idols were set in the sun. Thou didst show to the sun thy shame and to the moon thy madness.’

And the Man made answer and said, ‘Even so did I.’

And a third time God opened the Book of the Life of the Man.

And God said to the Man, ‘Evil hath been thy life, and with evil didst thou requite good, and with wrongdoing kindness. The hands that fed thee thou didst wound, and the breasts that gave thee suck thou didst despise. He who came to thee with water went away thirsting, and the outlawed men who hid thee in their tents at night thou didst betray before dawn. Thine enemy who spared thee thou didst snare in an ambush and the friend who walked with thee thou didst sell for a price, and to those who brought thee Love thou didst ever give Lust in thy turn.’

And the Man made answer and said, ‘Even so did I.’

And God closed the Book of the Life of the Man, and said, ‘Surely I will send thee into Hell. Even into Hell will I send thee.’

And the Man cried out, ‘Thou canst not.’

And God said to the Man, ‘Wherefore can I not send thee to Hell, and for what reason?’

‘Because in Hell have I always lived,’ answered the Man.

And there was silence in the House of Judgment.

And after a space God spake, and said to the Man, ‘Seeing that I may not send thee into Hell, surely I will send thee unto Heaven. Even unto Heaven will I send thee.’

And the Man cried out, ‘Thou canst not.’

And God said to the Man, ‘Wherefore can I not send thee unto Heaven, and for what reason?’

‘Because never, and in no place, have I been able to imagine it,’ answered the Man.

And there was silence in the House of Judgment.

Oscar Wilde 1894

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive W-X, Wilde, Oscar, Wilde, Oscar

Franz Kafka

Franz Kafka

Eine alltägliche Verwirrung

Ein alltäglicher Vorfall: sein Ertragen eine alltägliche Verwirrung. A hat mit B aus H ein wichtiges Geschäft abzuschließen. Er geht zur Vorbesprechung nach H, legt den Hin- und Herweg in je zehn Minuten zurück und rühmt sich zu Hause dieser besonderen Schnelligkeit. Am nächsten Tag geht er wieder nach H, diesmal zum endgültigen Geschäftsabschluß. Da dieser voraussichtlich mehrere Stunden erfordern wird, geht A sehr früh morgens fort. Obwohl aber alle Nebenumstände, wenigstens nach A’s Meinung, völlig die gleichen sind wie im Vortag, braucht er diesmal zum Weg nach H zehn Stunden. Als er dort ermüdet abends ankommt, sagt man ihm, daß B, ärgerlich wegen A’s Ausbleiben, vor einer halben Stunden zu A in sein Dorf gegangen sei und sie sich eigentlich unterwegs hätten treffen müssen. Man rät A zu warten. A aber, in Angst wegen des Geschäftes, macht sich sofort auf und eilt nach Hause.

Diesmal legt er den Weg, ohne besonders darauf zu achten, geradezu in einem Augenblick zurück. Zu Hause erfährt er, B sei doch schon gleich früh gekommen – gleich nach dem Weggang A’s; ja, er habe A im Haustor getroffen, ihn an das Geschäft erinnert, aber A habe gesagt, er hätte jetzt keine Zeit, er müsse jetzt eilig fort.

Trotz diesem unverständlichen Verhalten A’s sei aber B doch hier geblieben, um auf A zu warten. Er habe zwar schon oft gefragt, ob A nicht schon wieder zurück sei, befinde sich aber noch oben in A’s Zimmer. Glücklich darüber, B jetzt noch zu sprechen und ihm alles erklären zu können, läuft A die Treppe hinauf. Schon ist er fast oben, da stolpert er, erleidet eine Sehnenzerrung und fast ohnmächtig vor Schmerz, unfähig sogar zu schreien, nur winselnd im Dunkel hört er, wie B – undeutlich ob in großer Ferne oder knapp neben ihm – wütend die Treppe hinunterstampft und endgültig verschwindet.

Franz Kafka

(1883-1924)

Eine alltägliche Verwirrung

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Franz Kafka, Kafka, Franz, Kafka, Franz

DADALENIN reconstructs and speculates about how Dada and Lenin had more in common than is usually assumed. The book points to some of the tragicomic aspects of their parallel and overlapping artistic and political histories in order to question the unfulfilled legacy of the avant-garde. In Rainer Ganahl’s voluminous series of works DADA and Lenin are abundant sources of historical imagination. To dive into the historical situation Ganahl uses a variety of artistic media and techniques–ranging from animation movies to theatre performances, from ink drawings to bronze sculptures, departing from a number of historical details and catch phrases, from the no-man’s land between porn, terror and the history of the avant-gardes.

DADALENIN reconstructs and speculates about how Dada and Lenin had more in common than is usually assumed. The book points to some of the tragicomic aspects of their parallel and overlapping artistic and political histories in order to question the unfulfilled legacy of the avant-garde. In Rainer Ganahl’s voluminous series of works DADA and Lenin are abundant sources of historical imagination. To dive into the historical situation Ganahl uses a variety of artistic media and techniques–ranging from animation movies to theatre performances, from ink drawings to bronze sculptures, departing from a number of historical details and catch phrases, from the no-man’s land between porn, terror and the history of the avant-gardes.

Dadalenin

Rainer Ganahl

Publisher Taube

ISBN 9783981451849

608 p,

ills in colour & bw,

15 x 23 cm, hb, English

€25.00

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, Archive G-H, Art & Literature News, Dada, DADA, Dadaïsme

Shortlist Libris Literatuur Prijs 2017

Shortlist Libris Literatuur Prijs 2017

De schrijvers Walter van den Berg, Alfred Birney, Arnon Grunberg, Jeroen Olyslaegers, Marja Pruis en Lize Spit maken nog kans op het winnen van de prestigieuze Libris Literatuur Prijs en de bijbehorende 50.000 euro.

De vakjury, die naast Janine van den Ende (medeoprichter en bestuurslid VandenEnde Foundation) bestaat uit Kees ’t Hart, Michel Krielaars, Anna Luyten en Marrigje Paijmans, zal op 8 mei a.s. bekend maken welke van deze zes romans zij als de beste van het afgelopen jaar beschouwt. Nieuwsuur zendt die avond live een reportage uit van de prijsuitreiking in het Amstel Hotel te Amsterdam. Vorig jaar won Connie Palmen de prijs met Jij zegt het.

De zes genomineerde auteurs ontvingen elk 2.500 euro.

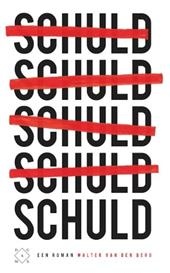

Schuld

Schuld

Walter van den Berg

Welkom in het universum van Walter van den Berg: de harde wereld van Amsterdam Nieuw-West. Waar mannen hangen in snackbars, rijden in Nissan Sunny’s en lopen op badslippers – en hun vrouw slaan. De pientere Kevin maakt gejatte laptops schoon en verkoopbaar. Vieze filmpjes die hij hierbij vindt zet hij online en de vreemdgangers belt hij op. Om ze te laten zien dat het hun schuld is. Om maar met iemand te kunnen praten. Maar dan komt zijn vader, ex-charmezanger ‘Zingende Ron’, uit de bak. Sommige schulden worden nooit afgelost.

De tolk van Java

De tolk van Java

Alfred Birney

Voor een Helmondse schoenmakersdochter, een Indische voormalige oorlogstolk en hun zoon – de verteller – bestaat er geen heden. Er is alleen een belast verleden: de jeugd van de moeder tijdens de Tweede Wereldoorlog in Brabant; de jeugd van de vader, die na de oorlog van Oost-Java naar Nederland vlucht; en de jeugd van de verteller die, geterroriseerd door zijn paranoïde vader, zijn tienerjaren op een internaat doorbrengt. Jarenlang zal hij zijn ouders achtervolgen met vragen over de oorlog, die ook hij als een zware last met zich meedraagt. Hun verhalen zijn spannend, hilarisch, gruwelijk, treurig en rauw. Hun onderlinge verhouding is afwijkend: ze zijn eerder tot elkaar veroordeeld dan dat ze een liefhebbende band hebben, met de herinnering als hun gezamenlijke vijand.

Moedervlekken

Moedervlekken

Arnon Grunberg

Otto Kadoke werkt als psychiater in een crisiscentrum: zijn specialiteit is suicide-preventie, hij dient mensen met een doodswens voor het leven te behouden. Wanneer hij op een dag bij zijn oude en hulpbehoevende moeder op bezoek gaat, doet een van de Nepalese verzorgsters de deur open, gehuld in slechts een handdoek. De psychiater, die zich altijd aan het protocol houdt, wordt overmand door gevoelens van liefde voor het meisje, met als gevolg dat hij de verzorging voor zijn moeder voortaan alleen dient te organiseren.

Kadoke is kinderloos, van middelbare leeftijd, maar niet onaantrekkelijk voor artsen in opleiding: hij heeft er menig weten te verleiden. Na opnieuw een grensoverschrijdende ontmoeting, ditmaal met een suïcidale jonge vrouw, lopen het professionele en privéleven van Kadoke definitief in het honderd: zijn moeders huis wordt een ambulant crisiscentrum.

Moedervlekken is een genadeloos eerlijke roman over de liefde van een zoon voor zijn moeder en vader, en vice versa. Een boek over twee mensen die niet kunnen leven – en niet dood kunnen gaan – zonder elkaar. Het markeert een nieuwe fase in Arnon Grunberg’s veelomvattende schrijverschap: zorg en liefde sluiten elkaar niet langer uit. Ondanks verlies en pijn blijkt het mogelijk liefde voor het leven te voelen.

Wil

Wil

Jeroen Olyslaegers

Het is oorlog. Antwerpen wordt bezet door geweld en wantrouwen. Wilfried Wils acht zichzelf een dichter in wording, maar moet tegelijk zien te overleven als hulpagent. De mooie Yvette wordt verliefd op hem en haar broer Lode is een waaghals die zijn nek uitsteekt voor joden. Wilfrieds artistieke mentor, Nijdig Baardje, wil juist alle joden vernietigen. Onbehaaglijk laverend tussen twee werelden, probeert Wilfried te overleven terwijl de jacht op de joden onverminderd verdergaat. Jaren later vertelt hij zijn verhaal aan een van zijn nakomelingen. Een ambitieuze, veelzijdige roman die de lezer niet los zal laten. Olyslaegers bewees zijn meesterschap al eerder, maar met WIL zal hij menigeen volstrekt verrassen.

Zachte riten

Zachte riten

Marja Pruis

‘Lucas zwemt voor me uit, met zijn korte krachtige slag. Hij zweeft op een vaste afstand in mijn geheugen, waarom kan ik hem niet inhalen, terwijl ik denk dat ik almaar harder zwem?’ Guusje Bouhuys, poëziedocente, huisvriendin, zus, heeft haar leven op de rem gezet. Als haar beste vriend wordt beschuldigd van plagiaat en een dierbare collega doodziek blijkt, beseft ze dat ze haar zorgvuldig geconserveerde universum zal moeten verlaten. In een absorberende stijl, ironisch en bitterzoet, schrijft Marja Pruis over het verlangen trouw te blijven aan de mensen die met je meelopen, ook als ze er niet meer zijn. Kun je een ander redden, behoeden voor de val? Kun je jezelf bewaren als in een gedicht? Zachte riten gaat over de conflictsituaties van de menselijke ziel, de betekenis van poëzie en de plaats van liefde in ons leven. Marja Pruis schreef onder meer de veelgeprezen romans De vertrouweling en Atoomgeheimen en het biografische portret Als je weg bent. Over Patricia de Martelaere, dat vijf drukken behaalde. Ze is gerenommeerd criticus en columniste voor De Groene Amsterdammer. Haar essaybundel Kus me, straf me. Over lezen en schrijven, liefde en verraad werd genomineerd voor de AKO Literatuurprijs en won de Jan Hanlo Essayprijs.

Het smelt

Het smelt

Lize Spit

1988 is een bijzonder jaar voor het kleine, Vlaamse Bovenmeer: behalve Eva worden er slechts twee andere kinderen geboren, Pim en Laurens. De drie maken er hun hele jeugd samen het beste van. Tot de bloedhete zomer van 2002; de jongens worden pubers met snode plannen. De verlegen Eva kan meedoen of oprotten. Die keuze is geen keuze.

De Libris Literatuur Prijs wordt toegekend voor de beste oorspronkelijk Nederlandstalige roman. Met de prijs is een geldbedrag van in totaal 65.000 euro gemoeid (2.500 euro voor de zes genomineerde auteurs en 50.000 euro voor de winnaar). De prijs is gemodelleerd naar de Britse Booker Prize. Dat houdt in dat er een longlist wordt gemaakt, gevolgd door zes nominaties, waarna tot slot de prijswinnaar wordt bekend gemaakt tijdens het traditionele galadiner in het Amstel Hotel te Amsterdam. De voorzitter komt uit een maatschappelijke sector buiten de literatuur. De overige vier leden zijn werkzaam als literatuurwetenschapper, criticus en/of auteur.

# Meer informatie op website Libris Literatuur Prijs

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Bookstores, Arnon Grunberg, Art & Literature News, Awards & Prizes, FICTION & NONFICTION ARCHIVE, Literary Events

The Doctors of Hoyland

The Doctors of Hoyland

by Arthur Conan Doyle

Dr. James Ripley was always looked upon as an exceedingly lucky dog by all of the profession who knew him. His father had preceded him in a practice in the village of Hoyland, in the north of Hampshire, and all was ready for him on the very first day that the law allowed him to put his name at the foot of a prescription. In a few years the old gentleman retired, and settled on the South Coast, leaving his son in undisputed possession of the whole country side. Save for Dr. Horton, near Basingstoke, the young surgeon had a clear run of six miles in every direction, and took his fifteen hundred pounds a year, though, as is usual in country practices, the stable swallowed up most of what the consulting-room earned.

Dr. James Ripley was two-and-thirty years of age, reserved, learned, unmarried, with set, rather stern features, and a thinning of the dark hair upon the top of his head, which was worth quite a hundred a year to him. He was particularly happy in his management of ladies. He had caught the tone of bland sternness and decisive suavity which dominates without offending. Ladies, however, were not equally happy in their management of him. Professionally, he was always at their service. Socially, he was a drop of quicksilver. In vain the country mammas spread out their simple lures in front of him. Dances and picnics were not to his taste, and he preferred during his scanty leisure to shut himself up in his study, and to bury himself in Virchow’s Archives and the professional journals.

Study was a passion with him, and he would have none of the rust which often gathers round a country practitioner. It was his ambition to keep his knowledge as fresh and bright as at the moment when he had stepped out of the examination hall. He prided himself on being able at a moment’s notice to rattle off the seven ramifications of some obscure artery, or to give the exact percentage of any physiological compound. After a long day’s work he would sit up half the night performing iridectomies and extractions upon the sheep’s eyes sent in by the village butcher, to the horror of his housekeeper, who had to remove the debris next morning. His love for his work was the one fanaticism which found a place in his dry, precise nature.

It was the more to his credit that he should keep up to date in his knowledge, since he had no competition to force him to exertion. In the seven years during which he had practised in Hoyland three rivals had pitted themselves against him, two in the village itself and one in the neighbouring hamlet of Lower Hoyland. Of these one had sickened and wasted, being, as it was said, himself the only patient whom he had treated during his eighteen months of ruralising. A second had bought a fourth share of a Basingstoke practice, and had departed honourably, while a third had vanished one September night, leaving a gutted house and an unpaid drug bill behind him. Since then the district had become a monopoly, and no one had dared to measure himself against the established fame of the Hoyland doctor.

It was, then, with a feeling of some surprise and considerable curiosity that on driving through Lower Hoyland one morning he perceived that the new house at the end of the village was occupied, and that a virgin brass plate glistened upon the swinging gate which faced the high road. He pulled up his fifty guinea chestnut mare and took a good look at it. “Verrinder Smith, M. D.,” was printed across it in very neat, small lettering. The last man had had letters half a foot long, with a lamp like a fire-station. Dr. James Ripley noted the difference, and deduced from it that the new-comer might possibly prove a more formidable opponent. He was convinced of it that evening when he came to consult the current medical directory. By it he learned that Dr. Verrinder Smith was the holder of superb degrees, that he had studied with distinction at Edinburgh, Paris, Berlin, and Vienna, and finally that he had been awarded a gold medal and the Lee Hopkins scholarship for original research, in recognition of an exhaustive inquiry into the functions of the anterior spinal nerve roots. Dr. Ripley passed his fingers through his thin hair in bewilderment as he read his rival’s record. What on earth could so brilliant a man mean by putting up his plate in a little Hampshire hamlet.

But Dr. Ripley furnished himself with an explanation to the riddle. No doubt Dr. Verrinder Smith had simply come down there in order to pursue some scientific research in peace and quiet. The plate was up as an address rather than as an invitation to patients. Of course, that must be the true explanation. In that case the presence of this brilliant neighbour would be a splendid thing for his own studies. He had often longed for some kindred mind, some steel on which he might strike his flint. Chance had brought it to him, and he rejoiced exceedingly.

And this joy it was which led him to take a step which was quite at variance with his usual habits. It is the custom for a new-comer among medical men to call first upon the older, and the etiquette upon the subject is strict. Dr. Ripley was pedantically exact on such points, and yet he deliberately drove over next day and called upon Dr. Verrinder Smith. Such a waiving of ceremony was, he felt, a gracious act upon his part, and a fit prelude to the intimate relations which he hoped to establish with his neighbour.

The house was neat and well appointed, and Dr. Ripley was shown by a smart maid into a dapper little consulting room. As he passed in he noticed two or three parasols and a lady’s sun bonnet hanging in the hall. It was a pity that his colleague should be a married man. It would put them upon a different footing, and interfere with those long evenings of high scientific talk which he had pictured to himself. On the other hand, there was much in the consulting room to please him. Elaborate instruments, seen more often in hospitals than in the houses of private practitioners, were scattered about. A sphygmograph stood upon the table and a gasometer-like engine, which was new to Dr. Ripley, in the corner. A book-case full of ponderous volumes in French and German, paper-covered for the most part, and varying in tint from the shell to the yoke of a duck’s egg, caught his wandering eyes, and he was deeply absorbed in their titles when the door opened suddenly behind him. Turning round, he found himself facing a little woman, whose plain, palish face was remarkable only for a pair of shrewd, humorous eyes of a blue which had two shades too much green in it. She held a pince-nez in her left hand, and the doctor’s card in her right.

“How do you do, Dr. Ripley?” said she.

“How do you do, madam?” returned the visitor. “Your husband is perhaps out?”

“I am not married,” said she simply.

“Oh, I beg your pardon! I meant the doctor—Dr. Verrinder Smith.”

“I am Dr. Verrinder Smith.”

Dr. Ripley was so surprised that he dropped his hat and forgot to pick it up again.

“What!” he grasped, “the Lee Hopkins prizeman! You!”

He had never seen a woman doctor before, and his whole conservative soul rose up in revolt at the idea. He could not recall any Biblical injunction that the man should remain ever the doctor and the woman the nurse, and yet he felt as if a blasphemy had been committed. His face betrayed his feelings only too clearly.

“I am sorry to disappoint you,” said the lady drily.

“You certainly have surprised me,” he answered, picking up his hat.

“You are not among our champions, then?”

“I cannot say that the movement has my approval.”

“And why?”

“I should much prefer not to discuss it.”

“But I am sure you will answer a lady’s question.”

“Ladies are in danger of losing their privileges when they usurp the place of the other sex. They cannot claim both.”

“Why should a woman not earn her bread by her brains?”

Dr. Ripley felt irritated by the quiet manner in which the lady cross-questioned him.

“I should much prefer not to be led into a discussion, Miss Smith.”

“Dr. Smith,” she interrupted.

“Well, Dr. Smith! But if you insist upon an answer, I must say that I do not think medicine a suitable profession for women and that I have a personal objection to masculine ladies.”

It was an exceedingly rude speech, and he was ashamed of it the instant after he had made it. The lady, however, simply raised her eyebrows and smiled.

“It seems to me that you are begging the question,” said she. “Of course, if it makes women masculine that WOULD be a considerable deterioration.”

It was a neat little counter, and Dr. Ripley, like a pinked fencer, bowed his acknowledgment.

“I must go,” said he.

“I am sorry that we cannot come to some more friendly conclusion since we are to be neighbours,” she remarked.

He bowed again, and took a step towards the door.

“It was a singular coincidence,” she continued, “that at the instant that you called I was reading your paper on ‘Locomotor Ataxia,’ in the Lancet.”

“Indeed,” said he drily.

“I thought it was a very able monograph.”

“You are very good.”

“But the views which you attribute to Professor Pitres, of Bordeaux, have been repudiated by him.”

“I have his pamphlet of 1890,” said Dr. Ripley angrily.

“Here is his pamphlet of 1891.” She picked it from among a litter of periodicals. “If you have time to glance your eye down this passage——”

Dr. Ripley took it from her and shot rapidly through the paragraph which she indicated. There was no denying that it completely knocked the bottom out of his own article. He threw it down, and with another frigid bow he made for the door. As he took the reins from the groom he glanced round and saw that the lady was standing at her window, and it seemed to him that she was laughing heartily.

All day the memory of this interview haunted him. He felt that he had come very badly out of it. She had showed herself to be his superior on his own pet subject. She had been courteous while he had been rude, self-possessed when he had been angry. And then, above all, there was her presence, her monstrous intrusion to rankle in his mind. A woman doctor had been an abstract thing before, repugnant but distant. Now she was there in actual practice, with a brass plate up just like his own, competing for the same patients. Not that he feared competition, but he objected to this lowering of his ideal of womanhood. She could not be more than thirty, and had a bright, mobile face, too. He thought of her humorous eyes, and of her strong, well-turned chin. It revolted him the more to recall the details of her education. A man, of course, could come through such an ordeal with all his purity, but it was nothing short of shameless in a woman.

But it was not long before he learned that even her competition was a thing to be feared. The novelty of her presence had brought a few curious invalids into her consulting rooms, and, once there, they had been so impressed by the firmness of her manner and by the singular, new-fashioned instruments with which she tapped, and peered, and sounded, that it formed the core of their conversation for weeks afterwards. And soon there were tangible proofs of her powers upon the country side. Farmer Eyton, whose callous ulcer had been quietly spreading over his shin for years back under a gentle regime of zinc ointment, was painted round with blistering fluid, and found, after three blasphemous nights, that his sore was stimulated into healing. Mrs. Crowder, who had always regarded the birthmark upon her second daughter Eliza as a sign of the indignation of the Creator at a third helping of raspberry tart which she had partaken of during a critical period, learned that, with the help of two galvanic needles, the mischief was not irreparable. In a month Dr. Verrinder Smith was known, and in two she was famous.

Occasionally, Dr. Ripley met her as he drove upon his rounds. She had started a high dogcart, taking the reins herself, with a little tiger behind. When they met he invariably raised his hat with punctilious politeness, but the grim severity of his face showed how formal was the courtesy. In fact, his dislike was rapidly deepening into absolute detestation. “The unsexed woman,” was the description of her which he permitted himself to give to those of his patients who still remained staunch. But, indeed, they were a rapidly-decreasing body, and every day his pride was galled by the news of some fresh defection. The lady had somehow impressed the country folk with almost superstitious belief in her power, and from far and near they flocked to her consulting room.

Occasionally, Dr. Ripley met her as he drove upon his rounds. She had started a high dogcart, taking the reins herself, with a little tiger behind. When they met he invariably raised his hat with punctilious politeness, but the grim severity of his face showed how formal was the courtesy. In fact, his dislike was rapidly deepening into absolute detestation. “The unsexed woman,” was the description of her which he permitted himself to give to those of his patients who still remained staunch. But, indeed, they were a rapidly-decreasing body, and every day his pride was galled by the news of some fresh defection. The lady had somehow impressed the country folk with almost superstitious belief in her power, and from far and near they flocked to her consulting room.

But what galled him most of all was, when she did something which he had pronounced to be impracticable. For all his knowledge he lacked nerve as an operator, and usually sent his worst cases up to London. The lady, however, had no weakness of the sort, and took everything that came in her way. It was agony to him to hear that she was about to straighten little Alec Turner’s club foot, and right at the fringe of the rumour came a note from his mother, the rector’s wife, asking him if he would be so good as to act as chloroformist. It would be inhumanity to refuse, as there was no other who could take the place, but it was gall and wormwood to his sensitive nature. Yet, in spite of his vexation, he could not but admire the dexterity with which the thing was done. She handled the little wax-like foot so gently, and held the tiny tenotomy knife as an artist holds his pencil. One straight insertion, one snick of a tendon, and it was all over without a stain upon the white towel which lay beneath. He had never seen anything more masterly, and he had the honesty to say so, though her skill increased his dislike of her. The operation spread her fame still further at his expense, and self-preservation was added to his other grounds for detesting her. And this very detestation it was which brought matters to a curious climax.

One winter’s night, just as he was rising from his lonely dinner, a groom came riding down from Squire Faircastle’s, the richest man in the district, to say that his daughter had scalded her hand, and that medical help was needed on the instant. The coachman had ridden for the lady doctor, for it mattered nothing to the Squire who came as long as it were speedily. Dr. Ripley rushed from his surgery with the determination that she should not effect an entrance into this stronghold of his if hard driving on his part could prevent it. He did not even wait to light his lamps, but sprang into his gig and flew off as fast as hoof could rattle. He lived rather nearer to the Squire’s than she did, and was convinced that he could get there well before her.

And so he would but for that whimsical element of chance, which will for ever muddle up the affairs of this world and dumbfound the prophets. Whether it came from the want of his lights, or from his mind being full of the thoughts of his rival, he allowed too little by half a foot in taking the sharp turn upon the Basingstoke road. The empty trap and the frightened horse clattered away into the darkness, while the Squire’s groom crawled out of the ditch into which he had been shot. He struck a match, looked down at his groaning companion, and then, after the fashion of rough, strong men when they see what they have not seen before, he was very sick.

The doctor raised himself a little on his elbow in the glint of the match. He caught a glimpse of something white and sharp bristling through his trouser leg half way down the shin.

“Compound!” he groaned. “A three months’ job,” and fainted.

When he came to himself the groom was gone, for he had scudded off to the Squire’s house for help, but a small page was holding a gig-lamp in front of his injured leg, and a woman, with an open case of polished instruments gleaming in the yellow light, was deftly slitting up his trouser with a crooked pair of scissors.

“It’s all right, doctor,” said she soothingly. “I am so sorry about it. You can have Dr. Horton to-morrow, but I am sure you will allow me to help you to-night. I could hardly believe my eyes when I saw you by the roadside.”

“The groom has gone for help,” groaned the sufferer.

“When it comes we can move you into the gig. A little more light, John! So! Ah, dear, dear, we shall have laceration unless we reduce this before we move you. Allow me to give you a whiff of chloroform, and I have no doubt that I can secure it sufficiently to——”

Dr. Ripley never heard the end of that sentence. He tried to raise a hand and to murmur something in protest, but a sweet smell was in his nostrils, and a sense of rich peace and lethargy stole over his jangled nerves. Down he sank, through clear, cool water, ever down and down into the green shadows beneath, gently, without effort, while the pleasant chiming of a great belfry rose and fell in his ears. Then he rose again, up and up, and ever up, with a terrible tightness about his temples, until at last he shot out of those green shadows and was in the light once more. Two bright, shining, golden spots gleamed before his dazed eyes. He blinked and blinked before he could give a name to them. They were only the two brass balls at the end posts of his bed, and he was lying in his own little room, with a head like a cannon ball, and a leg like an iron bar. Turning his eyes, he saw the calm face of Dr. Verrinder Smith looking down at him.

“Ah, at last!” said she. “I kept you under all the way home, for I knew how painful the jolting would be. It is in good position now with a strong side splint. I have ordered a morphia draught for you. Shall I tell your groom to ride for Dr. Horton in the morning?”

“I should prefer that you should continue the case,” said Dr. Ripley feebly, and then, with a half hysterical laugh,—“You have all the rest of the parish as patients, you know, so you may as well make the thing complete by having me also.”

It was not a very gracious speech, but it was a look of pity and not of anger which shone in her eyes as she turned away from his bedside.

Dr. Ripley had a brother, William, who was assistant surgeon at a London hospital, and who was down in Hampshire within a few hours of his hearing of the accident. He raised his brows when he heard the details.

“What! You are pestered with one of those!” he cried.

“I don’t know what I should have done without her.”

“I’ve no doubt she’s an excellent nurse.”

“She knows her work as well as you or I.”

“Speak for yourself, James,” said the London man with a sniff. “But apart from that, you know that the principle of the thing is all wrong.”

“You think there is nothing to be said on the other side?”

“Good heavens! do you?”

“Well, I don’t know. It struck me during the night that we may have been a little narrow in our views.”

“Nonsense, James. It’s all very fine for women to win prizes in the lecture room, but you know as well as I do that they are no use in an emergency. Now I warrant that this woman was all nerves when she was setting your leg. That reminds me that I had better just take a look at it and see that it is all right.”

“I would rather that you did not undo it,” said the patient. “I have her assurance that it is all right.”

Brother William was deeply shocked.

“Of course, if a woman’s assurance is of more value than the opinion of the assistant surgeon of a London hospital, there is nothing more to be said,” he remarked.

“I should prefer that you did not touch it,” said the patient firmly, and Dr. William went back to London that evening in a huff.

The lady, who had heard of his coming, was much surprised on learning his departure.

“We had a difference upon a point of professional etiquette,” said Dr. James, and it was all the explanation he would vouchsafe.

For two long months Dr. Ripley was brought in contact with his rival every day, and he learned many things which he had not known before. She was a charming companion, as well as a most assiduous doctor. Her short presence during the long, weary day was like a flower in a sand waste. What interested him was precisely what interested her, and she could meet him at every point upon equal terms. And yet under all her learning and her firmness ran a sweet, womanly nature, peeping out in her talk, shining in her greenish eyes, showing itself in a thousand subtle ways which the dullest of men could read. And he, though a bit of a prig and a pedant, was by no means dull, and had honesty enough to confess when he was in the wrong.

“I don’t know how to apologise to you,” he said in his shame-faced fashion one day, when he had progressed so far as to be able to sit in an arm-chair with his leg upon another one; “I feel that I have been quite in the wrong.”

“Why, then?”

“Over this woman question. I used to think that a woman must inevitably lose something of her charm if she took up such studies.”

“Oh, you don’t think they are necessarily unsexed, then?” she cried, with a mischievous smile.

“Please don’t recall my idiotic expression.”

“I feel so pleased that I should have helped in changing your views. I think that it is the most sincere compliment that I have ever had paid me.”

“At any rate, it is the truth,” said he, and was happy all night at the remembrance of the flush of pleasure which made her pale face look quite comely for the instant.

For, indeed, he was already far past the stage when he would acknowledge her as the equal of any other woman. Already he could not disguise from himself that she had become the one woman. Her dainty skill, her gentle touch, her sweet presence, the community of their tastes, had all united to hopelessly upset his previous opinions. It was a dark day for him now when his convalescence allowed her to miss a visit, and darker still that other one which he saw approaching when all occasion for her visits would be at an end. It came round at last, however, and he felt that his whole life’s fortune would hang upon the issue of that final interview. He was a direct man by nature, so he laid his hand upon hers as it felt for his pulse, and he asked her if she would be his wife.

“What, and unite the practices?” said she.

He started in pain and anger.

“Surely you do not attribute any such base motive to me!” he cried. “I love you as unselfishly as ever a woman was loved.”

“No, I was wrong. It was a foolish speech,” said she, moving her chair a little back, and tapping her stethoscope upon her knee. “Forget that I ever said it. I am so sorry to cause you any disappointment, and I appreciate most highly the honour which you do me, but what you ask is quite impossible.”

With another woman he might have urged the point, but his instincts told him that it was quite useless with this one. Her tone of voice was conclusive. He said nothing, but leaned back in his chair a stricken man.

“I am so sorry,” she said again. “If I had known what was passing in your mind I should have told you earlier that I intended to devote my life entirely to science. There are many women with a capacity for marriage, but few with a taste for biology. I will remain true to my own line, then. I came down here while waiting for an opening in the Paris Physiological Laboratory. I have just heard that there is a vacancy for me there, and so you will be troubled no more by my intrusion upon your practice. I have done you an injustice just as you did me one. I thought you narrow and pedantic, with no good quality. I have learned during your illness to appreciate you better, and the recollection of our friendship will always be a very pleasant one to me.”

And so it came about that in a very few weeks there was only one doctor in Hoyland. But folks noticed that the one had aged many years in a few months, that a weary sadness lurked always in the depths of his blue eyes, and that he was less concerned than ever with the eligible young ladies whom chance, or their careful country mammas, placed in his way.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (1859 – 1930)

Round the Red Lamp: Being Facts and Fancies of Medical Life

The Doctors of Hoyland (#14)

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Doyle, Arthur Conan, Doyle, Arthur Conan, DRUGS & DISEASE & MEDICINE & LITERATURE, Round the Red Lamp

Boekenweekgeschenk van Herman Koch

Cadeau van uw boekhandel bij besteding van € 12,50 aan Nederlandstalige boeken

Synopsis Makkelijk leven

Tom Sanders is een gevierd schrijver van zelfhulpboeken en hij leidt een gelukkig leven met Julia en twee volwassen zonen, van wie de jongste, Stefan, zijn oogappel is. Tijdens een verjaardagsfeestje voor Julia staat hun schoondochter Hanna – op wie Tom en Julia niet dol zijn – opeens voor de deur. Snikkend vertelt ze dat ze door Stefan is geslagen en dat dat niet de eerste keer is. Moet Tom zijn lievelingszoon Stefan aanspreken op zijn gedrag? Of loont het misschien meer om de adviezen uit zijn zelfhulpboeken in praktijk te brengen, zoals zijn bekende richtlijn ‘Probeer problemen niet altijd op te lossen door eraan te denken; vaak worden ze eerder opgelost door er niet aan te denken’?

Thema Verboden vruchten

De mens is genotzuchtig. Maar toegeven aan genot levert soms strijd op, met ons geweten, onze levensovertuiging, onze omgeving en onze fysieke dan wel geestelijke grenzen. Wel willen, niet mogen, toch doen: verboden vruchten, zowel in het leven als in de letteren. Wie kent ze niet: de drank- en drugsverslaafden in Meriswin (Hafid Bouazza), Hallo Muur (Erik Jan Harmens), Angst en walging in Las Vegas (Hunter S. Thomson) en  Naamloos (Pepijn Lanen), de gokkers in Alles of niets (Khalid Boudou), de seksjunks in De 120 dagen van Sodom (Marquis de Sade), Mieke Maaike’s obscene jeugd (Louis Paul Boon) en Lolita (Nabokov), de troosteters in Chocolat (Joanne Harris), de vreetzakken in de Romeinse klassieker Satyricon (passage Het feestmaal bij Trimalchio) en de kannabalist in De maagd Marino (Yves Petry). En natuurlijk de overspeligen zoals beschreven in De buitenvrouw (Joost Zwagerman), Godin, held (Gustaaf Peek), Komt een vrouw bij de dokter(Kluun) en Mélodie d’Amour (Margriet de Moor).

Naamloos (Pepijn Lanen), de gokkers in Alles of niets (Khalid Boudou), de seksjunks in De 120 dagen van Sodom (Marquis de Sade), Mieke Maaike’s obscene jeugd (Louis Paul Boon) en Lolita (Nabokov), de troosteters in Chocolat (Joanne Harris), de vreetzakken in de Romeinse klassieker Satyricon (passage Het feestmaal bij Trimalchio) en de kannabalist in De maagd Marino (Yves Petry). En natuurlijk de overspeligen zoals beschreven in De buitenvrouw (Joost Zwagerman), Godin, held (Gustaaf Peek), Komt een vrouw bij de dokter(Kluun) en Mélodie d’Amour (Margriet de Moor).

Boekenweekessay bij het thema Verboden vruchten

Voor maar € 3,50 in uw boekwinkel

Libris Literatuur Prijswinnares Connie Palmen (Prometheus) schreef het Boekenweekessay 2017 bij het thema van de Boekenweek 2017: Verboden vruchten. Titel: De zonde van de vrouw.

In de bibliotheek

De Boekenweek is het literaire hoogtepunt van het jaar. De Openbare Bibliotheken grijpen dit evenement jaarlijks aan om de mooiste boeken te presenteren die zij in huis hebben. Uiteraard heeft de bibliotheek ook veel boeken bij het thema van de Boekenweek 2017: Verboden vruchten. (lees op deze pagina meer over het thema).

Boekenweekmagazine: haal gratis bij de bibliotheek

BOEKENWEEK 2017 van 25 maart tot en met 2 april

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book Lovers, - Bookstores, Boekenweek, FICTION & NONFICTION ARCHIVE, Illustrators, Illustration, Joost Zwagerman, Literary Events, Louis Paul Boon, Marquis de Sade

Sibylla Schwarz

Wie kan der Liebe Joch doch süß und lieblich seyn

Wie kan der Liebe Joch doch süß und lieblich seyn,

weil manches Herze pflegt vohn ihren Schmertzen sagen,

und über ihre Last, und tieffe Wunden klagen?

wie ist dan süße das, das allen bringet Pein,

das wie ein starckes Gifft die Hertzen nimmet ein,

das manchen Helden würgt, ihr vihl auch heist verzagen?

wie kan uns das alsdan doch Frewd und Lust erjagen?

Nein, nein, der Liebe Tranck ist bitter Wermuhtwein.

Doch gleichwohl ist sie süß, weil vielen wird gegeben,

durch ihre Süßigkeit, ein angenehmes Leben.

Drüm / schließ ich, ist die Lieb ein angenehmes Leid;

(wiewohl eß selten kompt, daß wiedrig’ Eigenschafften

an einem Dinge nuhr zu gleiche können hafften)

die Liebe heisst und ist die süße Bitterkeit.

Sibylla Schwarz (1621 – 1638)

Gedicht: Wie kan der Liebe Joch doch süß und lieblich seyn

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, SIbylla Schwarz

Guillaume Apollinaire

(1880 – 1918)

La fumée de la cantine

La fumée de la cantine est comme la nuit qui vient

Voix hautes ou graves le vin saigne partout

Je tire ma pipe libre et fier parmi mes camarades

Ils partirons avec moi pour les champs de bataille

Ils dormirons la nuit sous la pluie ou les étoiles

Ils galoperont avec moi portant en croupe des victoires

Ils obéiront avec moi aux mêmes commandements

Ils écouteront attentifs les sublimes fanfares

Ils mourront près de moi et moi peut-être près d’eux

Ils souffriront du froid et du soleil avec moi

Ils sont des hommes ceux-ci qui boivent avec moi

Ils obéissent avec moi aux lois de l’homme

Ils regardent sur les routes les femmes qui passent

Ils les désirent mais moi j’ai des plus hautes amours

Qui règnent sur mon coeur mes sens et mon cerveau

Et qui sont ma patrie ma famille et mon espérance

À moi soldat amoureux soldat de la douce France

Guillaume Apollinaire Poèmes à Lou

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: #Archive Concrete & Visual Poetry, *War Poetry Archive, Apollinaire, Guillaume, Archive A-B

Hart Crane

(1889 – 1932)

Passage

Where the cedar leaf divides the sky

I heard the sea.

In sapphire arenas of the hills

I was promised an improved infancy.

Sulking, sanctioning the sun,

My memory I left in a ravine,-

Casual louse that tissues the buck-wheat,

Aprons rocks, congregates pears

In moonlit bushels

And wakens alleys with a hidden cough.

Dangerously the summer burned

(I had joined the entrainments of the wind).

The shadows of boulders lengthened my back:

In the bronze gongs of my cheeks

The rain dried without odour.

“It is not long, it is not long;

See where the red and black

Vine-stanchioned valleys-“: but the wind

Died speaking through the ages that you know

And bug, chimney-sooted heart of man!

So was I turned about and back, much as your smoke

Compiles a too well-known biography.

The evening was a spear in the ravine

That throve through very oak. And had I walked

The dozen particular decimals of time?

Touching an opening laurel, I found

A thief beneath, my stolen book in hand.

“‘Why are you back here-smiling an iron coffin?

” “To argue with the laurel,” I replied:

“Am justified in transience, fleeing

Under the constant wonder of your eyes-.”

He closed the book. And from the Ptolemies

Sand troughed us in a glittering,, abyss.

A serpent swam a vertex to the sun

-On unpaced beaches leaned its tongue and

drummed.

What fountains did I hear? What icy speeches?

Memory, committed to the page, had broke.

Hart Crane poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive C-D, Crane, Hart

Genomineerden E. du Perronprijs 2016: Rodaan Al Galidi, Stefan Hertmans en Carolijn Visser – Arnon Grunberg houdt bij de prijsuitreiking de E. du Perronlezing donderdagavond 13 april 2017 in Tilburg

Genomineerden E. du Perronprijs 2016: Rodaan Al Galidi, Stefan Hertmans en Carolijn Visser – Arnon Grunberg houdt bij de prijsuitreiking de E. du Perronlezing donderdagavond 13 april 2017 in Tilburg

De schrijvers Rodaan Al Galidi, Stefan Hertmans en Carolijn Visser zijn genomineerd voor de E. du Perronprijs 2016. De prijs wordt toegekend aan personen of instellingen die met een cultuuruiting in brede zin een bijdrage leveren aan een beter begrip van de multiculturele samenleving. De uitreiking vindt plaats op donderdagavond 13 april 2017 bij het brabants kenniscentrum kunst en cultuur (bkkc) in Tilburg. Dan houdt Arnon Grunberg de E. du Perronlezing met als titel ‘Het paradijs’.

Rodaan Al Galidi – Hoe ik talent voor het leven kreeg (Uitgeverij Jurgen Maas)

Rodaan Al Galidi – Hoe ik talent voor het leven kreeg (Uitgeverij Jurgen Maas)

Rodaan Al Galidi doet ons verslag van de leerschool die de Nederlandse asielprocedure is. Negen jaar wacht de hoofdpersoon Semmier Kariem op een beschikking in een van de vestigingen van het AZC. Negen jaar tussen aankomst in Nederland op de vlucht voor fysieke bedreiging en definitieve toelating wordt in dit verhaal invoelbaar als een oneindige mentale nekklem. Dat is het leergeld voor vluchtelingen die niet op uitnodiging de landsgrenzen passeren. Leerschool of wachtkamer, het talent van Rodaan Al Galidi is gerijpt. Deze vertellingen in de vorm van brieven aan een geïnteresseerde buitenstaander gericht laten ons alle kanten van hoop, lethargie, opstandigheid, beklag en ironie zien. De bewoners van het AZC leven op een mix van herinneringen, volharding, wanhoop; kortom overlevingsdrift. Het verslag is introspectief, zakelijk, ironisch en soms ronduit Kafkaësk. Met zijn stijl schraagt de verteller zijn bestaan en geeft hij vaart aan een eindeloos vertraagde tijd.

Stefan Hertmans – De bekeerlinge (Uitgeverij De Bezige Bij)

Stefan Hertmans – De bekeerlinge (Uitgeverij De Bezige Bij)

Bekering is een van de meest ingrijpende keuzes die een mens kan maken. Zij rukt het individu uit zijn vertrouwde verband dat bepaald wordt door afstamming en traditie. Toebehoren biedt vertrouwdheid en bescherming. Dit aanbod, deze burcht af te wijzen en te verlaten, te vluchten is een onomkeerbare daad. De bekeerling moet koersen op onbekende instrumenten: een nieuw geloof, een vreemde taal, een onbekend bestaan in een onbekend gebied. Stefan Hertmans voert ons mee in het historische verhaal van Vigdis Adelaïs, die uit liefde besluit een Joodse jongeman te volgen. Het is het einde van de 11e eeuw. Het sentiment van kruistochten hangt in de lucht. Een millennium later volgt Hertmans deze vlucht, fysiek door het landschap met gebruikmaking van bronnen en verbeelding. Verstoting, bedreiging en vlucht zijn van alle tijden. Hertmans is in staat om op heel persoonlijke manier het universele en bijzondere hiervan open te schrijven in een overtuigende roman.

Carolijn Visser – Selma. Aan Hitler ontsnapt, gevangene van Mao (Uitgeverij Augustus)

Carolijn Visser – Selma. Aan Hitler ontsnapt, gevangene van Mao (Uitgeverij Augustus)

De titel van deze documentaire vertelling herinnert ons onmiddellijk aan het literaire cliché dat niets zo onwaarschijnlijk is als het leven zelf. Selma, een Joodse overlevende van de Holocaust, besluit met haar Chinese echtgenoot mee te gaan naar China in de jaren vijftig. Wat haar te wachten staat is het lot van intellectuelen en buitenlanders in de periode van de Culturele Revolutie. Het is de verdienste van Carolijn Visser om het onbeschrijfelijke glashelder aan ons te presenteren. Dat doet ze door vaardig te beschrijven wat er aan informatie bewaard is gebleven, maar net zo goed door betekenisvolle leemtes achter te laten. Selma is twee keer slachtoffer geworden van etnische uitsluiting. Ze staat niet voor grotere gehelen, ze was een individu dat voortdurend onder bedreiging van grotere verbanden, ideologieën leefde en uiteindelijk ook vermalen werd. Selma is een monument voor het kwetsbare individu.

E. du Perronprijs

E. du Perronprijs

De E. du Perronprijs is een initiatief van de gemeente Tilburg, de School of Humanities van Tilburg University en brabants kenniscentrum kunst en cultuur (bkkc). De prijs is bedoeld voor personen of instellingen die, net als Du Perron in zijn tijd, grenzen signaleren en doorbreken die wederzijds begrip tussen verschillende bevolkingsgroepen in de weg staan. De prijs bestaat uit een geldbedrag van €2500 euro en een textiel object, ontworpen door [NAAM] en vervaardigd bij het TextielMuseum. In 2015 won Ilja Leonard Pfeijffer de prijs voor zijn dichtbundel Idyllen, zijn pamflet Gelukszoekers en zijn columns in NRC Next. Andere laureaten waren onder meer Warna Oosterbaan & Theo Baart (2014), Mohammed Benzakour (2013), Koen Peeters (2012), Ramsey Nasr (2011), Alice Boot & Rob Woortman (2010), Abdelkader Benali (2009) en Adriaan van Dis (2008).

# Meer informatie over de du Perronprijs op website Tilburg University

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book Lovers, Abdelkader Benali, Archive O-P, Art & Literature News, Eddy du Perron, Hertmans, Stefan, Literary Events

WIT LICHT

Wit licht uit de hutten

wit de witte graanschuren

wit de rode bomen, wit de zwarte dieren

wit de adem van het dorp

die wit boven de hutten van wit riet hangt

Het licht wit het stof van de zwarte straten

wit stof wit de bruine ezels

wit stof wit de zwarte kinderen

zwarte kinderen zijn wit

in wit licht

zwarte kinderen zijn witter dan wit

Het witte stof wit het licht

het witte stof van de witte straat

het witte stof

van de witbestoven ezels

het witte licht van de zwarte kinderen

die wit stof tegen het witte licht blazen

Ton van Reen

Ton van Reen: De naam van het mes. Afrikaanse gedichten

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive Q-R, FDM in Africa, Reen, Ton van

The Griffin and the Minor Canon

The Griffin and the Minor Canon

by Frank Stockton

Over the great door of an old, old church which stood in a quiet town of a faraway land there was carved in stone the figure of a large griffin. The old-time sculptor had done his work with great care, but the image he had made was not a pleasant one to look at. It had a large head, with enormous open mouth and savage teeth; from its back arose great wings, armed with sharp hooks and prongs; it had stout legs in front, with projecting claws, but there were no legs behind–the body running out into a long and powerful tail, finished off at the end with a barbed point. This tail was coiled up under him, the end sticking up just back of his wings.

The sculptor, or the people who had ordered this stone figure, had evidently been very much pleased with it, for little copies of it, also of stone, had been placed here and there along the sides of the church, not very far from the ground so that people could easily look at them, and ponder on their curious forms. There were a great many other sculptures on the outside of this church–saints, martyrs, grotesque heads of men, beasts, and birds, as well as those of other creatures which cannot be named, because nobody knows exactly what they were; but none were so curious and interesting as the great griffin over the door, and the little griffins on the sides of the church.

A long, long distance from the town, in the midst of dreadful wilds scarcely known to man, there dwelt the Griffin whose image had been put up over the church door. In some way or other, the old-time sculptor had seen him and afterward, to the best of his memory, had copied his figure in stone.

The Griffin had never known this, until, hundreds of years afterward, he heard from a bird, from a wild animal, or in some manner which it is not now easy to find out, that there was a likeness of him on the old church in the distant town.

Now, this Griffin had no idea how he looked. He had never seen a mirror, and the streams where he lived were so turbulent and violent that a quiet piece of water, which would reflect the image of anything looking into it, could not be found. Being, as far as could be ascertained, the very last of his race, he had never seen another griffin. Therefore it was that, when he heard of this stone image of himself, he became very anxious to know what he looked like, and at last he determined to go to the old church, and see for himself what manner of being he was.

So he started off from the dreadful wilds, and flew on and on until he came to the countries inhabited by men, where his appearance in the air created great consternation; but he alighted nowhere, keeping up a steady flight until he reached the suburbs of the town which had his image on its church. Here, late in the afternoon, he lighted in a green meadow by the side of a brook, and stretched himself on the grass to rest. His great wings were tired, for he had not made such a long flight in a century, or more.

The news of his coming spread quickly over the town, and the people, frightened nearly out of their wits by the arrival of so strange a visitor, fled into their houses, and shut themselves up. The Griffin called loudly for someone to come to him but the more he called, the more afraid the people were to show themselves. At length he saw two laborers hurrying to their homes through the fields, and in a terrible voice he commanded them to stop. Not daring to disobey, the men stood, trembling.

“What is the matter with you all?” cried the Griffin. “Is there not a man in your town who is brave enough to speak to me?”

“I think,” said one of the laborers, his voice shaking so that his words could hardly be understood, “that-perhaps–the Minor Canon–would come.”

“Go, call him, then” said the Griffin; “I want to see him.”

The Minor Canon, who was an assistant in the old church, had just finished the afternoon services, and was coming out of a side door, with three aged women who had formed the weekday congregation. He was a young man of a kind disposition, and very anxious to do good to the people of the town. Apart from his duties in the church, where he conducted services every weekday, he visited the sick and the poor, counseled and assisted persons who were in trouble, and taught a school composed entirely of the bad children in the town with whom nobody else would have anything to do. Whenever the people wanted something difficult done for them, they always went to the Minor Canon. Thus it was that the laborer thought of the young priest when he found that someone must come and speak to the Griffin.

The Minor Canon had not heard of the strange event, which was known to the whole town except himself and the three old women and when he was informed of it, and was told that the Griffin had asked to see him, he was greatly amazed and frightened.

“Me!” he exclaimed. “He has never heard of me! What should he want with me?”

“Oh! you must go instantly!” cried the two men. “He is very angry now because he has been kept waiting so long; and nobody knows what may happen if you don’t hurry to him.”

The poor Minor Canon would rather have had his hand cut off than go out to meet an angry Griffin but he felt that it was his duty to go for it would be a woeful thing if injury should come to the people of the town because he was not brave enough to obey the summons of the Griffin. So, pale and frightened, he started off.

‘Well,” said the Griffin, as soon as the young man came near, “I am glad to see that there is someone who has the courage to come to me.”

The Minor Canon did not feel very brave, but he bowed his head.

‘Is this the town,” said the Griffin, “where there is a church with a likeness of myself over one of the doors?”

The Minor Canon looked at the frightful creature before him and saw that it was, without doubt, exactly like the stone image on the church. “Yes,” he said, “you are right.”

“Well, then,” said the Griffin, “will you take me to it? I wish very much to see it.”

The Minor Canon instantly thought that if the Griffin entered the town without the people’s knowing what he came for, some of them would probably be frightened to death, and so he sought to gain time to prepare their minds.

‘It is growing dark, now,” he said, very much afraid, as he spoke, that his words might enrage the Griffin, “and objects on the front of the church cannot be seen clearly. It will be better to wait until morning, if you wish to get a good view of the stone image of yourself.”

“That will suit me very well,” said the Griffin. “I see you are a man of good sense. I am tired, and I will take a nap here on this soft grass, while I cool my tail in the little stream that runs near me. The end of my tail gets red-hot when I am angry or excited, and it is quite warm now. So you may go; but be sure and come early tomorrow morning, and show me the way to the church.”

The Minor Canon was glad enough to take his leave, and hurried into the town. In front of the church he found a great many people assembled to hear his report of his interview with the Griffin. When they found that he had not come to spread rum, but simply to see his stony likeness on the church, they showed neither relief nor gratification, but began to upbraid the Minor Canon for consenting to conduct the creature into the town.

‘What could I do?” cried the young man. “If I should not bring him he would come himself, and, perhaps, end by setting fire to the town with his red-hot tail.”

Still the people were not satisfied, and a great many plans were proposed to prevent the Griffin from coming into the town. Some elderly persons urged that the young men should go out and kill him; but the young men scoffed at such a ridiculous idea.

Then someone said that it would be a good thing to destroy the stone image, so that the Griffin would have no excuse for entering the town; and this plan was received with such favor that many of the people ran for hammers, chisels, and crowbars, with which to tear down and break up the stone griffin. But the Minor Canon resisted this plan with all the strength of his mind and body. He assured the people that this action would enrage the Griffin beyond measure, for it would be impossible to conceal from him that his image had been destroyed during the night. But the people were so determined to break up the stone griffin that the Minor Canon saw that there was nothing for him to do but to stay there and protect it. All night he walked up and down in front of the church door, keeping away the men who brought ladders, by which they might mount to the great stone griffin, and knock it to pieces with their hammers and crowbars. After many hours the people were obliged to give up their attempts, and went home to sleep; but the Minor Canon remained at his post till early morning, and then he hurried away to the field where he had left the Griffin.

The monster had just awakened, and rising to his forelegs and shaking himself he said that he was ready to go into the town. The Minor Canon, therefore, walked back, the Griffin flying slowly through the air, at a short distance above the head of his guide. Not a person was to be seen in the streets, and they went directly to the front of the church, where the Minor Canon pointed out the stone griffin.

The real Griffin settled down in the little square before the church and gazed earnestly at his sculptured likeness. For a long time he looked at it. First he put his head on one side, and then he put it on the other; then he shut his right eye and gazed with his left, after which he shut his left eye and gazed with his right. Then he moved a little to one side and looked at the image, then he moved the other way. After a while he said to the Minor Canon, who had been standing by all this time:

“It is, it must be, an excellent likeness! That breadth between the eyes, that expansive forehead, those massive jaws! I feel that it must resemble me. If there is any fault to find with it, it is that the neck seems a little stiff. But that is nothing. It is an admirable likeness–admirable!”

The Griffin sat looking at his image all the morning and all the afternoon. The Minor Canon had been afraid to go away and leave him, and had hoped all through the day that he would soon be satisfied with his inspection and fly away home. But by evening the poor young man was very tired, and felt that he must eat and sleep. He frankly said this to the Griffin, and asked him if he would not like something to eat. He said this because he felt obliged in politeness to do so, but as soon as he had spoken the words, he was seized with dread lest the monster should demand half a dozen babies, or some tempting repast of that kind.

“Oh, no,” said the Griffin; ‘I never eat between the equinoxes. At the vernal and at the autumnal equinox I take a good meal, and that lasts me for half a year. I am extremely regular in my habits, and do not think it healthful to eat at odd times. But if you need food, go and get it, and I will return to the soft grass where I slept last night and take another nap.”

The next day the Griffin came again to the little square before the church, and remained there until evening, steadfastly regarding the stone griffin over the door. The Minor Canon came out once or twice to look at him, and the Griffin seemed very glad to see him; but the young clergyman could not stay as he had done before, for he had many duties to perform. Nobody went to the church, but the people came to the Minor Canon’s house, and anxiously asked him how long the Griffin was going to stay.

“I do not know,” he answered, “but I think he will soon be satisfied with regarding his stone likeness, and then he will go away.”

But the Griffin did not go away. Morning after morning he came to the church; but after a time he did not stay there all day. He seemed to have taken a great fancy to the Minor Canon, and followed him about as he worked. He would wait for him at the side door of the church, for the Minor Canon held services every day, morning and evening, though nobody came now. “If anyone should come,” he said to himself, “I must be found at my post.” When the young man came out, the Griffin would accompany him in his visits to the sick and the poor, and would often look into the windows of the schoolhouse where the Minor Canon was teaching his unruly scholars. All the other schools were closed, but the parents of the Minor Canon’s scholars forced them to go to school, because they were so bad they could not endure them all day at home–Griffin or no Griffin. But it must be said they generally behaved very well when that great monster sat up on his tail and looked in at the schoolroom window.

When it was found that the Griffin showed no sign of going away, all the people who were able to do so left the town. The canons and the higher officers of the church had fled away during the first day of the Griffin’s visit, leaving behind only the Minor Canon and some of the men who opened the doors and swept the church. All the citizens who could afford it shut up their houses and traveled to distant parts, and only the working people and the poor were left behind. After some days these ventured to go about and attend to their business, for if they did not work they would starve. They were getting a little used to seeing the Griffin; and having been told that he did not eat between equinoxes, they did not feel so much afraid of him as before.

Day by day the Griffin became more and more attached to the Minor Canon. He kept near him a great part of the time, and often spent the night in front of the little house where the young clergyman lived alone. This strange companionship was often burdensome to the Minor Canon, but, on the other hand, he could not deny that he derived a great deal of benefit and instruction from it. The Griffin had lived for hundreds of years, and had seen much, and he told the Minor Canon many wonderful things.

“It is like reading an old book,” said the young clergyman to himself; “but how many books I would have had to read before I would have found out what the Griffin has told me about the earth, the air, the water, about minerals, and metals, and growing things, and all the wonders of the world!”

Thus the summer went on, and drew toward its close. And now the people of the town began to be very much troubled again.

“It will not be long,” they said, “before the autumnal equinox is here, and then that monster will want to eat. He will be dreadfully hungry, for he has taken so much exercise since his last meal. He will devour our children. Without doubt, he will eat them all. What is to be done?”

To this question no one could give an answer, but all agreed that the Griffin must not be allowed to remain until the approaching equinox. After talking over the matter a great deal, a crowd of the people went to the Minor Canon at a time when the Griffin was not with him.

‘It is all your fault,” they said, “that that monster is among us. You brought him here, and you ought to see that he goes away. It is only on your account that he stays here at all; for, although he visits his image every day, he is with you the greater part of the time. If you were not here, he would not stay. It is your duty to go away, and then he will follow you, and we shall be free from the dreadful danger which hangs over us.”

“Go away!” cried the Minor Canon, greatly grieved at being spoken to in such a way. “Where shall I go? If I go to some other town, shall I not take this trouble there? Have I a right to do that?”

“No,” said the people, “you must not go to any other town. There is no town far enough away. You must go to the dreadful wilds where the Griffin lives, and then he will follow you and stay there.”

They did not say whether or not they expected the Minor Canon to stay there also, and he did not ask them anything about it. He bowed his head, and went into his house to think. The more he thought, the more clear it became to his mind that it was his duty to go away, and thus free the town from the presence of the Griffin.

That evening he packed a leathern bag full of bread and meat, and early the next morning he set out or his journey to the dreadful wilds. It was a long, weary, and doleful journey, especially after he had gone beyond the habitations of men; but the Minor Canon kept on bravely, and never faltered.

The way was longer than he had expected, and his provisions soon grew so scanty that he was obliged to eat but a little every day; but he kept up his courage, and pressed on, and, after many days of toilsome travel, he reached the dreadful wilds.

When the Griffin found that the Minor Canon had left the town he seemed sorry, but showed no desire to go and look for him. After a few days had passed he became much annoyed, and asked some of the people where the Minor Canon had gone. But, although the citizens had been so anxious that the young clergyman should go to the dreadful wilds, thinking that the Griffin would immediately follow him, they were now afraid to mention the Minor Canon’s destination, for the monster seemed angry already, and if he should suspect their trick he would, doubtless, become very much enraged. So everyone said he did not know, and the Griffin wandered about disconsolate. One morning he looked into the Minor Canon’s schoolhouse, which was always empty now, and thought that it was a shame that everything should suffer on account of the young man’s absence.

“It does not matter so much about the church,” he said, “for nobody went there; but it is a pity about the school. I think I will teach it myself until he returns.”

It was the hour for opening the school, and the Griffin went inside and pulled the rope which rang the school bell. Some of the children who heard the bell ran in to see what was the matter, supposing it to be a joke of one of their companions; but when they saw the Griffin they stood astonished and scared.

“Go tell the other scholars,” said the monster, “that school is about to open, and that if they are not all here in ten minutes I shall come after them.”

In seven minutes every scholar was in place.

Never was seen such an orderly school. Not a boy or girl moved or uttered a whisper. The Griffin climbed into the master’s seat, his wide wings spread on each side of him, because he could not lean back in his chair while they stuck out behind, and his great tail coiled around, in front of the desk, the barbed end sticking up, ready to tap any boy or girl who might misbehave.

The Griffin now addressed the scholars, telling them that he intended to teach them while their master was away. In speaking he tried to imitate, as far as possible, the mild and gentle tones of the Minor Canon; but it must be admitted that in this he was not very successful. He had paid a good deal of attention to the studies of the school, and he determined not to try to teach them anything new, but to review them in what they had been studying; so he called up the various classes, and questioned them upon their previous lessons. The children racked their brains to remember what they had learned. They were so afraid of the Griffin’s displeasure that they recited as they had never recited before. One of the boys, far down in his class, answered so well that the Griffin was astonished.

‘I should think you would be at the head,” said he. “I am sure you have never been in the habit of reciting so well. Why is this?”

“Because I did not choose to take the trouble,” said the boy, trembling in his boots. He felt obliged to speak the truth, for all the children thought that the great eyes of the Griffin could see right through them, and that he would know when they told a falsehood.

“You ought to be ashamed of yourself,” said the Griffin. “Go down to the very tail of the class; and if you are not at the head in two days, I shall know the reason why.”

The next afternoon this boy was Number One.

It was astonishing how much these children now learned of what they had been studying. It was as if they had been educated over again. The Griffin used no severity toward them, but there was a look about him which made them unwilling to go to bed until they were sure they knew their lessons for the next day.

The Griffin now thought that he ought to visit the sick and the poor; and he began to go about the town for this purpose. The effect upon the sick was miraculous. All, except those who were very ill indeed, jumped from their beds when they heard he was coming, and declared themselves quite well. To those who could not get up he gave herbs and roots, which none of them had ever before thought of as medicines, but which the Griffin had seen used in various parts of the world; and most of them recovered. But, for all that, they afterward said that, no matter what happened to them, they hoped that they should never again have such a doctor coming to their bedsides, feeling their pulses and looking at their tongues.

As for the poor, they seemed to have utterly disappeared. All those who had depended upon charity for their daily bread were now at work in some way or other; many of them offering to do odd jobs for their neighbors just for the sake of their meals–a thing which before had been seldom heard of in the town. The Griffin could find no one who needed his assistance.

The summer had now passed, and the autumnal equinox was rapidly approaching. The citizens were in a state of great alarm and anxiety. The Griffin showed no signs of going away, but seemed to have settled himself permanently among them. In a short time the day for his semiannual meal would arrive, and then what would happen? The monster would certainly be very hungry, and would devour all their children.

Now they greatly regretted and lamented that they had sent away the Minor Canon; he was the only one on whom they could have depended in this trouble, for he could talk freely with the Griffin, and so find out what could be done. But it would not do to be inactive. Some step must be taken immediately. A meeting of the citizens was called, and two old men were appointed to go and talk to the Griffin. They were instructed to offer to prepare a splendid dinner for him on equinox day-one which would entirely satisfy his hunger. They would offer him the fattest mutton, the most tender beef fish, and game of various sorts, and anything of the kind that he might fancy. If none of these suited, they were to mention that there was an orphan asylum in the next town.

“Anything would be better,” said the citizens, “than to have our dear children devoured.”

The old men went to the Griffin; but their propositions were not received with favor.

“From what I have seen of the people of this town,” said the monster, “I do not think I could relish anything which was prepared by them. They appear to be all cowards and, therefore, mean and selfish. As for eating one of them, old or young, I could not think of it for a moment. In fact, there was only one creature in the whole place for whom I could have had any appetite, and that is the Minor Canon, who has gone away. He was brave, and good, and honest, and I think I should have relished him.”

“Ah!” said one of the old men very politely, “in that case I wish we had not sent him to the dreadful wilds!”

“What!” cried the Griffin. “What do you mean? Explain instantly what you are talking about!”

The old man, terribly frightened at what he had said, was obliged to tell how the Minor Canon had been sent away by the people, in the hope that the Griffin might be induced to follow him.

When the monster heard this he became furiously angry. He dashed away from the old men, and, spreading his wings, flew backward and forward over the town. He was so much excited that his tail became red-hot, and glowed like a meteor against the evening sky. When at last he settled down in the little field where he usually rested, and thrust his tail into the brook, the steam arose like a cloud, and the water of the stream ran hot through the town. The citizens were greatly frightened, and bitterly blamed the old man for telling about the Minor Canon.

“It is plain,” they said, “that the Griffin intended at last to go and look for him, and we should have been saved. Now who can tell what misery you have brought upon us.”

The Griffin did not remain long in the little field. As soon as his tail was cool he flew to the town hall and rang the bell. The citizens knew that they were expected to come there; and although they were afraid to go, they were still more afraid to stay away; and they crowded into the hall. The Griffin was on the platform at one end, flapping his wings and walking up and down, and the end of his tail was still so warm that it slightly scorched the boards as he dragged it after him.

When everybody who was able to come was there, the Griffin stood still and addressed the meeting.

‘I have had a very low opinion of you,” he said, “ever since I discovered what cowards you are, but I had no idea that you were so ungrateful, selfish, and cruel as I now find you to be. Here was your Minor Canon, who labored day and night for your good, and thought of nothing else but how he might benefit you and make you happy; and as soon as you imagine yourselves threatened with a danger–for well I know you are dreadfully afraid of me–you send him off, caring not whether he returns or perishes, hoping thereby to save yourselves. Now, I had conceived a great liking for that young man, and had intended, in a day or two, to go and look him up. But I have changed my mind about him. I shall go and find him, but I shall send him back here to live among you, and I intend that he shall enjoy the reward of his labor and his sacrifices.