Fleurs du Mal Magazine

THE PROMOTER

Even as early as September, in the year of 1870, the newly emancipated had awakened to the perception of the commercial advantages of freedom, and had begun to lay snares to catch the fleet and elusive dollar.

Those co ntroversialists who say that the Negro’s only idea of freedom was to live without work are either wrong, malicious, or they did not know Little Africa when the boom was on; when every little African, fresh from the fields and cabins, dreamed only of untold wealth and of mansions in which he would have been thoroughly uncomfortable.

ntroversialists who say that the Negro’s only idea of freedom was to live without work are either wrong, malicious, or they did not know Little Africa when the boom was on; when every little African, fresh from the fields and cabins, dreamed only of untold wealth and of mansions in which he would have been thoroughly uncomfortable.

These were the devil’s sunny days, and early and late his mowers were in the field. These were the days of benefit societies that only benefited the shrewdest man; of mutual insurance associations, of wild building companies, and of gilt-edged land schemes wherein the unwary became bogged. This also was the day of Mr. Jason Buford, who, having been free before the war, knew a thing or two, and now had set himself up as a promoter. Truly he had profited by the example of the white men for whom he had so long acted as messenger and factotum.

As he frequently remarked when for purposes of business he wished to air his Biblical knowledge, “I jest takes the Scripter fur my motter an’ foller that ol’ passage where it says, ‘Make hay while the sun shines, fur the night cometh when no man kin work.'”

It is related that one of Mr. Buford’s customers was an old plantation exhorter. At the first suggestion of a Biblical quotation the old gentleman closed his eyes and got ready with his best amen. But as the import of the words dawned on him he opened his eyes in surprise, and the amen died a-borning. “But do hit say dat?” he asked earnestly.

“It certainly does read that way,” said the promoter glibly.

“Uh, huh,” replied the old man, settling himself back in his chair. “I been preachin’ dat t’ing wrong fu’ mo’ dan fo’ty yeahs. Dat’s whut comes o’ not bein’ able to read de wo’d fu’ yo’se’f.”

Buford had no sense of the pathetic or he could never have done what he did—sell to the old gentleman, on the strength of the knowledge he had imparted to him, a house and lot upon terms so easy that he might drowse along for a little time and then wake to find himself both homeless and penniless. This was the promoter’s method, and for so long a time had it proved successful that he had now grown mildly affluent and had set up a buggy in which to drive about and see his numerous purchasers and tenants.

Buford was a suave little yellow fellow, with a manner that suggested the training of some old Southern butler father, or at least, an experience as a likely house-boy. He was polite, plausible, and more than all, resourceful. All of this he had been for years, but in all these years he had never so risen to the height of his own uniqueness as when he conceived and carried into execution the idea of the “Buford Colonizing Company.”

Humanity has always been looking for an Eldorado, and, however mixed the metaphor may be, has been searching for a Moses to lead it thereto. Behold, then, Jason Buford in the rôle of Moses. And equipped he was to carry off his part with the very best advantage, for though he might not bring water from the rock, he could come as near as any other man to getting blood from a turnip.

The beauty of the man’s scheme was that no offering was too small to be accepted. Indeed, all was fish that came to his net.

Think of paying fifty cents down and knowing that some time in the dim future you would be the owner of property in the very heart of a great city where people would rush to buy. It was glowing enough to attract a people more worldly wise than were these late slaves. They simply fell into the scheme with all their souls; and off their half dollars, dollars, and larger sums, Mr. Buford waxed opulent. The land meanwhile did not materialise.

It was just at this time that Sister Jane Callender came upon the scene and made glad the heart of the new-fledged Moses. He had heard of Sister Jane before, and he had greeted her coming with a sparkling of eyes and a rubbing of hands that betokened a joy with a good financial basis.

The truth about the newcomer was that she had just about received her pension, or that due to her deceased husband, and she would therefore be rich, rich to the point where avarice would lie in wait for her.

Sis’ Jane settled in Mr. Buford’s bailiwick, joined the church he attended, and seemed only waiting with her dollars for the very call which he was destined to make. She was hardly settled in a little three-room cottage before he hastened to her side, kindly intent, or its counterfeit, beaming from his features. He found a weak-looking old lady propped in a great chair, while another stout and healthy-looking woman ministered to her wants or stewed about the house in order to be doing something.

“Ah, which—which is Sis’ Jane Callender,” he asked, rubbing his hands for all the world like a clothing dealer over a good customer.

“Dat’s Sis’ Jane in de cheer,” said the animated one, pointing to her charge. “She feelin’ mighty po’ly dis evenin’. What might be yo’ name?” She was promptly told.

“Sis’ Jane, hyeah one de good brothahs come to see you to offah his suvices if you need anything.”

“Thanky, brothah, charity,” said the weak voice, “sit yo’se’f down. You set down, Aunt Dicey. Tain’t no use a runnin’ roun’ waitin’ on me. I ain’t long fu’ dis worl’ nohow, mistah.”

“Buford is my name an’ I came in to see if I could be of any assistance to you, a-fixin’ up yo’ mattahs er seein’ to anything for you.”

“Hit’s mighty kind o’ you to come, dough I don’ ‘low I’ll need much fixin’ fu’ now.”

“Oh, we hope you’ll soon be better, Sistah Callender.”

“Nevah no mo’, suh, ’til I reach the Kingdom.”

“Sis’ Jane Callender, she have been mighty sick,” broke in Aunt Dicey Fairfax, “but I reckon she gwine pull thoo’, the Lawd willin’.”

“Amen,” said Mr. Buford.

“Huh, uh, children, I done hyeahd de washin’ of de waters of Jerdon.”

“No, no, Sistah Callendah, we hope to see you well and happy in de injoyment of de pension dat I understan’ de gov’ment is goin’ to give you.”

“La, chile, I reckon de white folks gwine to git dat money. I ain’t nevah gwine to live to ‘ceive it. Des’ aftah I been wo’kin’ so long fu’ it, too.”

The small eyes of Mr. Buford glittered with anxiety and avarice. What, was this rich plum about to slip from his grasp, just as he was about to pluck it? It should not be. He leaned over the old lady with intense eagerness in his gaze.

“You must live to receive it,” he said, “we need that money for the race. It must not go back to the white folks. Ain’t you got nobody to leave it to?”

“Not a chick ner a chile, ‘ceptin’ Sis’ Dicey Fairfax here.”

Mr. Buford breathed again. “Then leave it to her, by all means,” he said.

“I don’ want to have nothin’ to do with de money of de daid,” said Sis’ Dicey Fairfax.

“Now, don’t talk dat away, Sis’ Dicey,” said the sick woman. “Brother Buford is right, case you sut’ny has been good to me sence I been layin’ hyeah on de bed of affliction, an’ dey ain’t nobody more fitterner to have dat money den you is. Ef de Lawd des lets me live long enough, I’s gwine to mek my will in yo’ favoh.”

“De Lawd’s will be done,” replied the other with resignation, and Mr. Buford echoed with an “Amen!”

He stayed very long that evening, planning and talking with the two old women, who received his words as the Gospel. Two weeks later the Ethiopian Banner, which was the organ of Little Africa, announced that Sis’ Jane Callender had received a back pension which amounted to more than five hundred dollars. Thereafter Mr. Buford was seen frequently in the little cottage, until one day, after a lapse of three or four weeks, a policeman entered Sis’ Jane Callender’s cottage and led her away amidst great excitement to prison. She was charged with pension fraud, and against her protestations, was locked up to await the action of the Grand Jury.

The promoter was very active in his client’s behalf, but in spite of all his efforts she was indicted and came up for trial.

It was a great day for the denizens of Little Africa, and they crowded the court room to look upon this stranger who had come among them to grow so rich, and then suddenly to fall so low.

The prosecuting attorney was a young Southerner, and when he saw the prisoner at the bar he started violently, but checked himself. When the prisoner saw him, however, she made no effort at self control.

“Lawd o’ mussy,” she cried, spreading out her black arms, “if it ain’t Miss Lou’s little Bobby.”

The judge checked the hilarity of the audience; the prosecutor maintained his dignity by main force, and the bailiff succeeded in keeping the old lady in her place, although she admonished him: “Pshaw, chile, you needn’t fool wid me, I nussed dat boy’s mammy when she borned him.”

It was too much for the young attorney, and he would have been less a man if it had not been. He came over and shook her hand warmly, and this time no one laughed.

It was really not worth while prolonging the case, and the prosecution was nervous. The way that old black woman took the court and its officers into her bosom was enough to disconcert any ordinary tribunal. She patronised the judge openly before the hearing began and insisted upon holding a gentle motherly conversation with the foreman of the jury.

She was called to the stand as the very first witness.

“What is your name?” asked the attorney.

“Now, Bobby, what is you axin’ me dat fu’? You know what my name is, and you one of de Fairfax fambly, too. I ‘low ef yo’ mammy was hyeah, she’d mek you ‘membah; she’d put you in yo’ place.”

The judge rapped for order.

“That is just a manner of proceeding,” he said; “you must answer the question, so the rest of the court may know.”

“Oh, yes, suh, ‘scuse me, my name hit’s Dicey Fairfax.”

The attorney for the defence threw up his hands and turned purple. He had a dozen witnesses there to prove that they had known the woman as Jane Callender.

“But did you not give your name as Jane Callender?”

“I object,” thundered the defence.

“Do, hush, man,” Sis’ Dicey exclaimed, and then turning to the prosecutor, “La, honey, you know Jane Callender ain’t my real name, you knows dat yo’se’f. It’s des my bus’ness name. W’y, Sis’ Jane Callender done daid an’ gone to glory too long ‘go fu’ to talk erbout.”

“Then you admit to the court that your name is not Jane Callender?”

“Wha’s de use o’ my ‘mittin’, don’ you know it yo’se’f, suh? Has I got to come hyeah at dis late day an’ p’ove my name an’ redentify befo’ my ol’ Miss’s own chile? Mas’ Bob, I nevah did t’ink you’d ac’ dat away. Freedom sutny has done tuk erway yo’ mannahs.”

“Yes, yes, yes, that’s all right, but we want to establish the fact that your name is Dicey Fairfax.”

“Cose it is.”

“Your Honor, I object—I——”

“Your Honor,” said Fairfax coldly, “will you grant me the liberty of conducting the examination in a way somewhat out of the ordinary lines? I believe that my brother for the defence will have nothing to complain of. I believe that I understand the situation and shall be able to get the truth more easily by employing methods that are not altogether technical.”

The court seemed to understand a thing or two himself, and overruled the defence’s objection.

“Now, Mrs. Fairfax——”

Aunt Dicey snorted. “Hoomph? What? Mis’ Fairfax? What ou say, Bobby Fairfax? What you call me dat fu’? My name Aunt Dicey to you an’ I want you to un’erstan’ dat right hyeah. Ef you keep on foolin’ wid me, I ‘spec’ my patience gwine waih claih out.”

“Excuse me. Well, Aunt Dicey, why did you take the name of Jane Callender if your name is really Dicey Fairfax?”

“W’y, I done tol’ you, Bobby, dat Sis’ Jane Callender was des’ my bus’ness name.”

“Well, how were you to use this business name?”

“Well, it was des dis away. Sis’ Jane Callender, she gwine git huh pension, but la, chile, she tuk down sick unto deaf, an’ Brothah Buford, he say dat she ought to mek a will in favoh of somebody, so’s de money would stay ‘mongst ouah folks, an’ so, bimeby, she ‘greed she mek a will.”

“And who is Brother Buford, Aunt Dicey?”

“Brothah Buford? Oh, he’s de gemman whut come an’ offered to ‘ten’ to Sis’ Jane Callender’s bus’ness fu’ huh. He’s a moughty clevah man.”

“And he told her she ought to make a will?”

“Yas, suh. So she ‘greed she gwine mek a will, an’ she say to me, ‘Sis Dicey, you sut’ny has been good to me sence I been layin’ hyeah on dis bed of ‘fliction, an’ I gwine will all my proputy to you.’ Well, I don’t want to tek de money, an’ she des mos’ nigh fo’ce it on me, so I say yes, an’ Brothah Buford he des sot an’ talk to us, an’ he say dat he come to-morror to bring a lawyer to draw up de will. But bless Gawd, honey, Sis’ Callender died dat night, an’ de will wasn’t made, so when Brothah Buford come bright an’ early next mornin’, I was layin’ Sis’ Callender out. Brothah Buford was mighty much moved, he was. I nevah did see a strange pusson tek anything so hard in all my life, an’ den he talk to me, an’ he say, ‘Now, Sis’ Dicey, is you notified any de neighbours yit?’ an’ I said no I hain’t notified no one of de neighbours, case I ain’t ‘quainted wid none o’ dem yit, an’ he say, ‘How erbout de doctah? Is he ‘quainted wid de diseased?’ an’ I tol’ him no, he des come in, da’s all. ‘Well,’ he say, ‘cose you un’erstan’ now dat you is Sis’ Jane Callender, caise you inhe’it huh name, an’ when de doctah come to mek out de ‘stiffycate, you mus’ tell him dat Sis’ Dicey Fairfax is de name of de diseased, an’ it’ll be all right, an’ aftah dis you got to go by de name o’ Jane Callender, caise it’s a bus’ness name you done inhe’it.’ Well, dat’s whut I done, an’ dat’s huccome I been Jane Callender in de bus’ness ‘sactions, an’ Dicey Fairfax at home. Now, you un’erstan’, don’t you? It wuz my inhe’ited name.”

“But don’t you know that what you have done is a penitentiary offence?”

“Who you stan’in’ up talkin’ to dat erway, you nasty impident little scoun’el? Don’t you talk to me dat erway. I reckon ef yo’ mammy was hyeah she sut’ny would tend to yo’ case. You alluse was sassier an’ pearter den yo’ brother Nelse, an’ he had to go an’ git killed in de wah, an’ you—you—w’y, jedge, I’se spanked dat boy mo’ times den I kin tell you fu’ hus impidence. I don’t see how you evah gits erlong wid him.”

The court repressed a ripple that ran around. But there was no smile on the smooth-shaven, clear-cut face of the young Southerner. Turning to the attorney for the defence, he said: “Will you take the witness?” But that gentleman, waving one helpless hand, shook his head.

“That will do, then,” said young Fairfax. “Your Honor,” he went on, addressing the court, “I have no desire to prosecute this case further. You all see the trend of it just as I see, and it would be folly to continue the examination of any of the rest of these witnesses. We have got that story from Aunt Dicey herself as straight as an arrow from a bow. While technically she is guilty; while according to the facts she is a criminal according to the motive and the intent of her actions, she is as innocent as the whitest soul among us.” He could not repress the youthful Southerner’s love for this little bit of rhetoric.

“And I believe that nothing is to be gained by going further into the matter, save for the purpose of finding out the whereabouts of this Brother Buford, and attending to his case as the facts warrant. But before we do this, I want to see the stamp of crime wiped away from the name of my Aunt Dicey there, and I beg leave of the court to enter a nolle prosse. There is only one other thing I must ask of Aunt Dicey, and that is that she return the money that was illegally gotten, and give us information concerning the whereabouts of Buford.”

Aunt Dicey looked up in excitement, “W’y, chile, ef dat money was got illegal, I don’ want it, but I do know whut I gwine to do, cause I done ‘vested it all wid Brothah Buford in his colorednization comp’ny.” The court drew its breath. It had been expecting some such dénouement.

“And where is the office of this company situated?”

“Well, I des can’t tell dat,” said the old lady. “W’y, la, man, Brothah Buford was in co’t to-day. Whaih is he? Brothah Buford, whaih you?” But no answer came from the surrounding spectators. Brother Buford had faded away. The old lady, however, after due conventions, was permitted to go home.

It was with joy in her heart that Aunt Dicey Fairfax went back to her little cottage after her dismissal, but her face clouded when soon after Robert Fairfax came in.

“Hyeah you come as usual,” she said with well-feigned anger. “Tryin’ to sof’ soap me aftah you been carryin’ on. You ain’t changed one mite fu’ all yo’ bein’ a man. What you talk to me dat away in co’t fu’?”

Fairfax’s face was very grave. “It was necessary, Aunt Dicey,” he said. “You know I’m a lawyer now, and there are certain things that lawyers have to do whether they like it or not. You don’t understand. That man Buford is a scoundrel, and he came very near leading you into a very dangerous and criminal act. I am glad I was near to save you.”

“Oh, honey, chile, I didn’t know dat. Set down an’ tell me all erbout it.”

This the attorney did, and the old lady’s indignation blazed forth. “Well, I hope to de Lawd you’ll fin’ dat rascal an’ larrup him ontwell he cain’t stan’ straight.”

“No, we’re going to do better than that and a great deal better. If we find him we are going to send him where he won’t inveigle any more innocent people into rascality, and you’re going to help us.”

“W’y, sut’ny, chile, I’ll do all I kin to he’p you git dat rascal, but I don’t know whaih he lives, case he’s allus come hyeah to see me.”

“He’ll come back some day. In the meantime we will be laying for him.”

Aunt Dicey was putting some very flaky biscuits into the oven, and perhaps the memory of other days made the young lawyer prolong his visit and his explanation. When, however, he left, it was with well-laid plans to catch Jason Buford napping.

It did not take long. Stealthily that same evening a tapping came at Aunt Dicey’s door. She opened it, and a small, crouching figure crept in. It was Mr. Buford. He turned down the collar of his coat which he had had closely up about his face and said:

“Well, well, Sis’ Callender, you sut’ny have spoiled us all.”

“La, Brothah Buford, come in hyeah an’ set down. Whaih you been?”

“I been hidin’ fu’ feah of that testimony you give in the court room. What did you do that fu’?”

“La, me, I didn’t know, you didn’t ‘splain to me in de fust.”

“Well, you see, you spoiled it, an’ I’ve got to git out of town as soon as I kin. Sis’ Callender, dese hyeah white people is mighty slippery, and they might catch me. But I want to beg you to go on away from hyeah so’s you won’t be hyeah to testify if dey does. Hyeah’s a hundred dollars of yo’ money right down, and you leave hyeah to-morrer mornin’ an’ go erway as far as you kin git.”

“La, man, I’s puffectly willin’ to he’p you, you know dat.”

“Cose, cose,” he answered hurriedly, “we col’red people has got to stan’ together.”

“But what about de res’ of dat money dat I been ‘vestin’ wid you?”

“I’m goin’ to pay intrus’ on that,” answered the promoter glibly.

“All right, all right.” Aunt Dicey had made several trips to the little back room just off her sitting room as she talked with the promoter. Three times in the window had she waved a lighted lamp. Three times without success. But at the last “all right,” she went into the room again. This time the waving lamp was answered by the sudden flash of a lantern outside.

“All right,” she said, as she returned to the room, “set down an’ lemme fix you some suppah.”

“I ain’t hardly got the time. I got to git away from hyeah.” But the smell of the new baked biscuits was in his nostrils and he could not resist the temptation to sit down. He was eating hastily, but with appreciation, when the door opened and two minions of the law entered.

Buford sprang up and turned to flee, but at the back door, her large form a towering and impassive barrier, stood Aunt Dicey.

“Oh, don’t hu’y, Brothah Buford,” she said calmly, “set down an’ he’p yo’se’f. Dese hyeah’s my friends.”

It was the next day that Robert Fairfax saw him in his cell. The man’s face was ashen with coward’s terror. He was like a caught rat though, bitingly on the defensive.

“You see we’ve got you, Buford,” said Fairfax coldly to him. “It is as well to confess.”

“I ain’t got nothin’ to say,” said Buford cautiously.

“You will have something to say later on unless you say it now. I don’t want to intimidate you, but Aunt Dicey’s word will be taken in any court in the United States against yours, and I see a few years hard labour for you between good stout walls.”

The little promoter showed his teeth in an impotent snarl. “What do you want me to do?” he asked, weakening.

“First, I want you to give back every cent of the money that you got out of Dicey Fairfax. Second, I want you to give up to every one of those Negroes that you have cheated every cent of the property you have accumulated by fraudulent means. Third, I want you to leave this place, and never come back so long as God leaves breath in your dirty body. If you do this, I will save you—you are not worth the saving—from the pen or worse. If you don’t, I will make this place so hot for you that hell will seem like an icebox beside it.”

The little yellow man was cowering in his cell before the attorney’s indignation. His lips were drawn back over his teeth in something that was neither a snarl nor a smile. His eyes were bulging and fear-stricken, and his hands clasped and unclasped themselves nervously.

“I—I——” he faltered, “do you want to send me out without a cent?”

“Without a cent, without a cent,” said Fairfax tensely.

“I won’t do it,” the rat in him again showed fight. “I won’t do it. I’ll stay hyeah an’ fight you. You can’t prove anything on me.”

“All right, all right,” and the attorney turned toward the door.

“Wait, wait,” called the man, “I will do it, my God! I will do it. Jest let me out o’ hyeah, don’t keep me caged up. I’ll go away from hyeah.”

Fairfax turned back to him coldly, “You will keep your word?”

“Yes.”

“I will return at once and take the confession.”

And so the thing was done. Jason Buford, stripped of his ill-gotten gains, left the neighbourhood of Little Africa forever. And Aunt Dicey, no longer a wealthy woman and a capitalist, is baking golden brown biscuits for a certain young attorney and his wife, who has the bad habit of rousing her anger by references to her business name and her investments with a promoter.

Paul Laurence Dunbar

(1872 – 1906)

The Promotor

From The Heart Of Happy Hollow, a collection of short stories reprinted in 1904 by Dodd, Mead and Company, New York.

Short Story

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive C-D, Archive C-D, Dunbar, Paul Laurence, Dunbar, Paul Laurence, Paul Laurence Dunbar, Paul Laurence Dunbar

Een wolk schuift voor de zon. De beelden van grootvader en het molenhuis lossen op. Mels hoort alleen nog de stemmen van het kerkhof. Als bijen zoemen ze rond zijn hoofd.

Er zijn ook stemmen die hij niet wil horen, maar het is moeilijk er zijn oren voor te sluiten. Hij hoort zijn vittende vader, die op hem kankert omdat hij lui en te speels is. `Je moet beter je best doen! Je verlummelt je tijd! Je bent net zo lui als je moeder, die zit ook altijd in de zon! Je denkt toch niet dat ik voor niets voor je werk! Zat je alweer in je bootje op de Wijer! Was je weer bij je grootvader Bernhard! Van die man leer je niets goeds!’

Er zijn ook stemmen die hij niet wil horen, maar het is moeilijk er zijn oren voor te sluiten. Hij hoort zijn vittende vader, die op hem kankert omdat hij lui en te speels is. `Je moet beter je best doen! Je verlummelt je tijd! Je bent net zo lui als je moeder, die zit ook altijd in de zon! Je denkt toch niet dat ik voor niets voor je werk! Zat je alweer in je bootje op de Wijer! Was je weer bij je grootvader Bernhard! Van die man leer je niets goeds!’

Hij rilt van afschuw. De kreten van zijn vader, die altijd terug blijven komen. Door zijn ongenoegen over het leven was hij zelf vroeg gestorven. Hij haatte de zon. Hij kende alleen plicht.

Om de stem van zijn vader terug te dringen in het graf, draait hij zijn hoofd weg en luistert naar de vogels die rond de silo vliegen. Hij wil nu niet denken. Het brengt de ergernis terug in zijn hoofd. Het wordt steeds moeilijker om die te onderdrukken. Zijn hersens raken erdoor op drift. Hij kan zich steeds minder goed beheersen. Zijn hoofd laat zich niet meer dwingen. Zijn hersens zijn aangetast. Hij herinnert zich dingen die hij niet meer kan plaatsen. Gesprekken die hij met Wilkington heeft gevoerd. Wilkington die hem vertelde hoe het bij hem thuis was. En over een kamertje dat bestemd was voor zijn zoon, maar dat altijd leeg was gebleven. Hij moet die gesprekken hebben gefantaseerd, want hij heeft Wilkington nooit gezien.

Nooit heeft hij geweten dat de graansilo zo veel vogels herbergde. Ze wonen in alle kieren en gaten. Ze vliegen door de kapotte ramen naar binnen en ze zingen en fluiten. Ze zijn vrolijk, maar misschien zouden ze zich ongerust moeten maken, nu Bouwbedrijf Leon van Wijk en Zonen een begin heeft gemaakt met de bouw van appartementen in de silo. De nesten zullen worden vernield.

Langgeleden is hij op het dak geweest, samen met Tijger en Thija. Twaalf jaar waren ze toen. Langs de stalen trap in de fabriek waren ze naar boven geklommen. Van boven had het dorp op een sprookjesdorp geleken.

Op hun rug hadden ze op het dak gelegen, met het gevoel veel dichter bij de wolken te zijn en er zo op te kunnen stappen om weg te zeilen. Onder een veel grotere hemel. En Thija had een gedicht van Jacob over zijn eenzaamheid voorgelezen.

De bouwlift komt omhoog en stopt. Hij hoort de stappen op het dak, achter zijn rug. Ze komen hem halen.

`Je zit hier mooi.’ Het is de stem van Tijger, achter hem, diep, zoals de stem van een zestigjarige. Hij schrikt niet eens dat Tijger zo dicht bij hem is.

Zijn vriend Tijger. In zijn dromen heeft hij altijd met Tijger gepraat. Soms was Tijger twaalf, maar vaak was hij net zo oud als hijzelf. In leeftijd blijkt hij gewoon meegegroeid, zoals een echte vriend voor het leven meegroeit.

`Kijk, het dak van mijn ouderlijk huis’, zegt Mels. `Ik ben er altijd gebleven. Ik heb er met mijn moeder gewoond tot ze stierf. Ik ben er gebleven toen ik trouwde. Als je erop neerkijkt, lijkt het heel mooi.’

`Op afstand is alles mooi’, zegt Tijger. `Maar het is écht een mooi dorp. Schilderachtig zelfs, omdat je nu de silo niet ziet. Als je beneden bent, zie je altijd die rottige toren.’

`Ze knappen de silo op’, zegt Mels. `Ze vinden hem mooi omdat hij oud is. Snap jij dat?’

`Oud is altijd mooi’, zegt Tijger. `Een natte oude krant die opdroogt in de zon wordt ook weer mooi. Ik blader graag in oude kranten. Op het kerkhof krijgen we geen andere kranten dan verwaaide oude kranten. Vaak zijn de letters bijna opgelost door zon en water. Je weet nooit precies wat je leest.’

`Zo is het met nieuw nieuws ook’, zegt Mels. `Je weet nooit precies wat ze je vertellen willen. Hoor jij de stemmen van beneden ook?’

`Waar praten ze over?’

`Veel zul je er niet meer van begrijpen. Alles is anders. Iedereen is anders. Bijna niemand van de mensen die hier nu wonen kent je nog.’

`En mijn zus?’

`Ze herinnert zich niet veel van je.’

`En mijn moeder?’

`Ze heeft zich opgehangen. Ze is nooit over het verlies van jou heen gekomen.’

`Wat spijt me dat’, zegt Tijger met een brok in zijn keel. `Als ik alles had geweten, zou ik niet zo’n waaghals zijn geweest.’

Hij loopt naar de rand van het dak en gaat zitten, zijn benen bungelend over de rand.

`Je bent nog net zo’n waaghals’, zegt Mels. Het valt hem op hoe kaal zijn vriend is geworden. Hij heeft veel weg van grootvader Bernhard.

`Ik wilde altijd alles voor honderd procent’, zegt Tijger.

`Als je toen niet verongelukt was, zou het later wel gebeurd zijn. Niet veel later. Als je zestien of twintig was geweest. Met jouw waaghalzerij zou je nooit oud zijn geworden.’

`Ik ben nooit bang geweest. Soms, in mijn slaap. Maar nu ben ik wel bang.’

`Waarvoor?’

`Voor het leven dat ik heb gemist.’

`Maar je bent teruggekomen.’

`Je weet het toch nog wel’, zegt Tijger. `John Wilkington. Je was er toch zeker van dat zijn ziel in jou doorleefde.’

`Dat denk ik nu nog.’

`De dochters van Wilkington hadden je zussen kunnen zijn.’

Mels is verbijsterd. Opeens begrijpt hij waarom zijn vader zo afstandelijk was. Dat hij nauwelijks woorden had voor zijn moeder. Dat hij altijd weg was.

`Je schrikt er toch niet van’, zegt Tijger. `Je bent uit liefde geboren, wat wil je meer? Zonder Wilkington op zolder was je er nooit geweest.’

`Je hebt gelijk. Ik moet hem dankbaar zijn.’

`Bovendien leef je voort. Je hebt een dochter. Kleinkinderen. Maar ik? Jij bent de enige die nog aan mij denkt. Straks, als jij ook weg bent, ben ik totaal vergeten. Dat maakt me bang. Ik ben bang voor de eenzaamheid. Om hier altijd te moeten blijven.’

`Misschien is het dat wat ze eeuwigheid noemen’, zegt Mels. `Dat je ergens voor altijd blijft.’

`Maar toch niet hier! Weet je nog dat wij vroeger ook wel eens stiekem op het dak van de silo stonden?’ Tijger schuift wat achteruit, trekt zijn benen op en gaat staan.

`Het is maar één keer gebeurd’, zegt Mels. `Toen Thija dat gedicht van Jacob las.’

`Vaker.’

`Dat herinner ik me niet.’

`Ik wilde vleugels maken, om naar beneden te zeilen.’

`Dat klopt. Jij wilde vliegen. Je hebt het niet geprobeerd. Je zou te pletter zijn gevallen.’

`Als iedereen zo denkt, durft niemand wat. Als niemand had willen vliegen, zouden er nog steeds geen vliegtuigen zijn.’

`Zou jij het vliegtuig hebben uitgevonden?’

`Dat denk ik wel. Als ik was blijven leven wel. Ik zou zeker hebben gevlogen.’

Ton van Reen: Het diepste blauw (104)

wordt vervolgd

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Het diepste blauw, Archive Q-R, Reen, Ton van

The Crowning Gift

I have had courage to accuse;

And a fine wit that could upbraid;

And a nice cunning that could bruise;

And a shrewd wisdom, unafraid

Of what weak mortals fear to lose.

I have had virtue to despise

The sophistry of pious fools;

I have had firmness to chastise;

And intellect to make me rules,

To estimate and exorcise.

I have had knowledge to be true;

My faith could obstacles remove;

But now, by failure taught anew,

I would have courage now to love,

And lay aside the strength I knew.

Gladys Cromwell

(1885-1919)

The Crowning Gift

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive C-D, Cromwell, Gladys, Gladys Cromwell

La Madone Amoureuse

Le ciel noir se piquait de torches résineuses,

Scintillantes lueurs, astres pâles d’amour.

Secouant du zénith leurs vapeurs lumineuses

En nuages d’encens au brasier du jour.

Se lustrait du vermeil bruni d’un disque pur,

Coeur jaunissant de fleur immobile et plantée

Comme une pâquerette aux mornes champs d’azur,

A travers l’infini sombre de l’étendue

La blancheur de la Vierge immense s’allongeait,

Colosse de vapeur vaguement épandue

Où le glaive éclatant de la lune plongeait.

Ce n’était plus le marbre aux arêtes précises

Où les Grecs découpaient la chair pâle des dieux,

Mais un esprit flottant en formes indécises

Et versant du brouillard vers la voûte des cieux.

Car l’idéal chrétien est fait de chair meurtrie,

Et d’orbites saignants et de membres broyés,

Tandis qu’abandonnant sa dépouille flétrie

L’âme ailée ouvre l’air de ses bras éployés.

Les dieux morts des anciens vivaient de notre vie;

Ils avaient nos amours; ils avaient nos douleurs;

Ils voyaient nos plaisirs en pâlissant d’envie

Et se vengeaient du rire en nous forçant aux pleurs.

Le Symbole vivant n’a que son existence

Dont la force idéale échappe à nos regards,

Et les martyrs en vain cloués sur leur potence

Interrogeaient l’éther avec leurs yeux hagards.

Mais l’élan passionné de la Vierge Marie

Avait noyé son âme en une ombre de chair

Faite de désirs fous, de luxure pétrie,

Où le cri de l’amour passait comme un éclair.

Cette chair transparente errait dans la pénombre,

Emergeait sous le froid de la Nuit, grelottait,

Et la Vierge trempée aux plis d’un voile sombre

Couvrait de ses deux mains son front et sanglotait.

Ses cheveux blonds coulaient en vagues dénouées

Qui ruisselaient à flots dans le fauve sillon

Des mamelles de brume à sa forme clouées

Par deux boutons puissants casqués de vermillon.

Et ses larmes roulaient en sanglantes rosées,

Jaillissant sous les cils parfumés de ses yeux

Comme un filet gonflé de leurs perles rosées,

Sa chevelure d’or tombait en plis soyeux.

Pendant qu’elle pleurait dans ses chairs cristallines,

Un nuage laiteux en panache fumait,

Fondant leur transparence en teintes opalines

Dont la neige mousseuse et légère écumait.

Et ses pâles cheveux aux couleurs effacées

Lentement noircissaient au creuset de la nuit,

Et l’or blond s’enfuyait de leurs teintes passées (5).

Ainsi que l’or mourant d’une braise s’enfuit

Ses veines se gonflaient de gouttes purpurines

Qui faisaient tressaillir ses nerfs en les baignant;

Un souffle sensuel dilatait ses narines

Et le désir perçait son coeur d’un clou saignant.

La blonde déité qui pleurait diaphane,

En cachant ses yeux bleus de ses longs doigts nacrés,

Avait pris les cheveux d’une brune profane

Et sa chair inhabile à des gestes sacrés.

Ce n’était plus la chaste et mystique Marie

Eclairée du halo pur de la Trinité,

Mais c’était une fille amoureuse, qui crie

Et gémit de désir sur sa virginité.

Elle entendait monter de langoureuses plaintes

De la vasque profonde où la Terre planait;

Le soupir attiédi des premières étreintes

En effluve d’amour vers sa bouche émanait.

Marcel Schwob

(1867-1905)

La Madone Amoureuse

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Archive S-T, Marcel Schwob

Bahnhofstrasse

The eyes that mock me sign the way

Whereto I pass at eve of day.

Grey way whose violet signals are

The trysting and the twining star.

Ah star of evil! star of pain!

Highhearted youth comes not again

Nor old heart’s wisdom yet to know

The signs that mock me as I go.

James Joyce

(1882-1941)

Bahnhofstrasse

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive I-J, Archive I-J, Joyce, James, Joyce, James

A Portrait of One: Harry Phelan Gibb

Some one in knowing everything is knowing that some one is something.

Some one in knowing everything is knowing that some one is something.

Some one is something and is succeeding is succeeding in hoping that thing.

He is suffering.

He is succeeding in hoping and he is succeeding in saying that that is something.

He is suffering, he is suffering and succeeding in hoping that in succeeding in saying that he is succeeding in hoping is something.

He is suffering, he is hoping, he is succeeding in saying that anything is something.

He is suffering, he is hoping, he is succeeding in saying that something is something.

He is hoping that he is succeeding in hoping that something is something.

He is hoping that he is succeeding in saying that he is succeeding in hoping that something is something.

He is hoping that he is succeeding in saying that something is something.

Gertrude Stein

(1874-1946)

A Portrait of One

Harry Phelan Gibb

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Archive S-T, Gertrude Stein, Stein, Gertrude

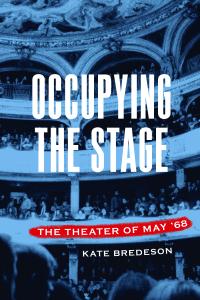

Occupying the Stage: the Theater of May ’68 tells the story of student and worker uprisings in France through the lens of theater history, and the story of French theater through the lens of May ’68.

Based on detailed archival research and original translations, close readings of plays and historical documents, and a rigorous assessment of avant-garde theater history and theory, Occupying the Stage proposes that the French theater of 1959–71 forms a standalone paradigm called “The Theater of May ’68.”

Based on detailed archival research and original translations, close readings of plays and historical documents, and a rigorous assessment of avant-garde theater history and theory, Occupying the Stage proposes that the French theater of 1959–71 forms a standalone paradigm called “The Theater of May ’68.”

The book shows how French theater artists during this period used a strategy of occupation-occupying buildings, streets, language, words, traditions, and artistic processes-as their central tactic of protest and transformation. It further proposes that the Theater of May ’68 has left imprints on contemporary artists and activists, and that this theater offers a scaffolding on which to build a meaningful analysis of contemporary protest and performance in France, North America, and beyond.

At the book’s heart is an inquiry into how artists of the period used theater as a way to engage in political work and, concurrently, questioned and overhauled traditional theater practices so their art would better reflect the way they wanted the world to be. Occupying the Stage embraces the utopic vision of May ’68 while probing the period’s many contradictions. It thus affirms the vital role theater can play in the ongoing work of social change.

Occupying the Stage

The Theater of May ’68

Kate Bredeson (Author)

Publication Date: November 2018

Pages 232

Trim Size 6 x 9

Paper Text – $34.95

Northwestern University Press

Drama & Performance Studies

ISBN 978-0-8101-3815-5

# new books

Occupying the Stage

The Theater of May ’68

Kate Bredeson

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: #Editors Choice Archiv, - Book News, - Book Stories, Archive A-B, Art & Literature News, AUDIO, CINEMA, RADIO & TV, Protests of MAY 1968, THEATRE

Grootvader Bernhard heeft een flesje in zijn hand en dept azijn op de arm van Thija, die door een bij is gestoken. Thija wordt vaak gestoken.

`Heb je de angel er uitgezogen?’ vraagt grootvader.

`Heb je de angel er uitgezogen?’ vraagt grootvader.

Thija laat het kleine zwarte puntje zien op de nagel van haar wijsvinger, maar door zijn kippige ogen ziet grootvader het niet.

`Rotbijen’, zegt Thija. `Waarom steken bijen vooral meisjes?’

`Meisjes hebben zoet bloed’, zegt grootvader. `Jullie zijn van suiker. Vroeger woonde er een meisje in ons dorp dat helemaal door de bijen is opgegeten. Van haar hebben ze alleen de botten teruggevonden.’

`Vorige week vertelde u dat ze door een wolf was opgegeten.’

`Zei ik dat? Dan moet ik me toen hebben vergist. Zie je, ik word oud. Ik haal de dingen door elkaar. Ik denk dat er twee meisjes zijn opgegeten, een door bijen en een door een wolf.’

`Dat van die wolf is waar’, zegt Mels. `Grootvader Rudolf vertelt het ook. In een strenge winter, langgeleden, zijn de wolven uit het bos gekomen en hebben een meisje opgegeten.’

`Ik denk dat Rudolf het verhaaltje over het meisje dat is opgegeten door de wolf zelf in omloop heeft gebracht.’

`Zoals u het praatje over het meisje dat is opgegeten door de bijen zelf hebt bedacht?’

`Zo zal het wel zijn gegaan’, lacht grootvader. `Oude mannen vertellen maar wat. Zo ontstaan verhalen. Sommigen schrijven ze op. En dat leren jullie dan op school als geschiedenis.’

Ton van Reen: Het diepste blauw (103)

wordt vervolgd

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, - Het diepste blauw, Archive Q-R, Reen, Ton van

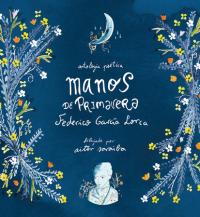

Manos de primavera. Antología poética de Federico García Lorca

Hands of Spring : Anthology of Poetry by Federico García Lorca

La voz de Lorca ilustrada por la mano poética de Aitor Saraiba.

La voz de Lorca ilustrada por la mano poética de Aitor Saraiba.

La luna, el agua, la tierra, las imágenes lorquianas caminan de la mano de las poéticas ilustraciones de Aitor Saraiba. Una defensa de las voces únicas y las imágenes indestructibles. Un libro, sí, un canto a la libertad y al arte.

Lorca’s voice, illustrated by the poetic hand of Aitor Saraiba.

The moon, water, earth: Lorca’s images go hand-in-hand with the poetic illustrations of Aitor Saraiba. A defense of unique voices and indestructible images. A book—and a song to freedom and art.

Manos de primavera. Antología poética de Federico García Lorca

Hands of Spring : Anthology of Poetry by Federico García Lorca

By Federico Garcia Lorca

Hardcover

Pages: 128

10 x 11

Aug 20, 2019

Published by Montena

PRH Grupo Editoria

Category: Poetry

Spanish Language Nonfiction

ISBN 9788417671419

ISBN-13: 9788417671419

$20.95

# More poetry

Anthology of Poetry

by Federico García Lorca

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: - Book News, 4SEASONS#Spring, Archive K-L, Archive K-L, Art & Literature News, Garcia Lorca, Federico, WAR & PEACE

Vlaanderen, o welig huis

Vlaandren, o welig huis waar we zijn als genoden

aan rijke taaflen! – daar nu glooiend zijn de weiên

van zomer-granen, die hunne aêmende ebbe breien

naar malvend Ooste’ en statig dagerade-roden,

dewijl de morge’ ontwaakt ten hemel en ter Leië -:

wie kan u weten, en in ‘t harte niet verblijên;

niet danke’ om dagen, schoon als jonge zege-goden,

gelijk een beedlaar dankt om warme tarwe-broden?…

o Vlaandren, blijde van uw gevens-rede handen,

zwaar, daar ge delend gaat, in paarse en gele wade,

der krachten die uw schoot als rodend ooft beladen.

– Vlaandren, wie wéet u en de zomer-dageraden,

en voelt geen rilde liefde in zijne leden branden

‘lijk deze morgen door de veië Leië-landen?

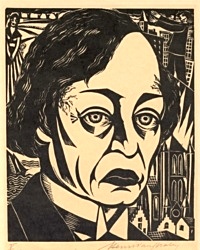

Karel van de Woestijne

(1878 – 1929)

Vlaanderen, o welig huis

Portret van Karel van de Woestijne (1937) door Henri van Straten (1892 – 1944)

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive W-X, Archive W-X, Woestijne, Karel van de

Fluch

Du sträubst und wehrst!

Die Brände heulen

Flammen

Sengen!

Nicht Ich

Nicht Du

Nicht Dich!

Mich!

Mich!

August Stramm

(1874-1915)

Fluch, 1914

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: *War Poetry Archive, Archive S-T, Expressionism, Stramm, August

De tentoonstelling ‘Art Brut | Jean Dubuffets revolutie in de kunst’ omvat ruim 150 werken waarmee kunstenaar en verzamelaar Jean Dubuffet in 1949 de bestaande culturele elite in Parijs choqueerde. De werken zijn zeventig jaar na dato voor het eerst te zien in Nederland.

Direct na de Tweede Wereldoorlog begint Jean Dubuffet zijn zoektocht naar nieuwe, zuivere en spontane kunstwerken, ver weg van de gevestigde orde. Tijdens zijn reis bezoekt hij psychiatrische instellingen, gevangenissen en verzamelt hij kindertekeningen en volkskunst. Bij de verschillende ontmoetingen collectioneert hij werken die volgens hem hét bewijs zijn dat deze kunstvorm een plaats verdient in de kunstwereld. De gevestigde uitgangspunten, de academische blik en standaarden moesten omver worden geworpen ten gunste van een nieuwe, zuivere en spontane kunst.

Direct na de Tweede Wereldoorlog begint Jean Dubuffet zijn zoektocht naar nieuwe, zuivere en spontane kunstwerken, ver weg van de gevestigde orde. Tijdens zijn reis bezoekt hij psychiatrische instellingen, gevangenissen en verzamelt hij kindertekeningen en volkskunst. Bij de verschillende ontmoetingen collectioneert hij werken die volgens hem hét bewijs zijn dat deze kunstvorm een plaats verdient in de kunstwereld. De gevestigde uitgangspunten, de academische blik en standaarden moesten omver worden geworpen ten gunste van een nieuwe, zuivere en spontane kunst.

Deze tentoonstelling biedt een reconstructie van de uitgangspunten van Art Brut aan de hand van de door Dubuffet bijeen gebrachte werken. Waarom kocht hij bepaalde werken aan en andere juist niet? Welke selectiecriteria hanteerde hij bij het collectioneren van werken en welke informatie verzamelde hij over de kunstenaars? Wat is er terecht gekomen van de kunstenaars waarvan Jean Dubuffet werk collectioneerde voor zijn Compagnie l’Art Brut?

Te zien zijn o.a. werken van door Dubuffet ontdekte grootheden zoals Aloïse Corbaz, Fleury-Joseph Crépin, Gaston Duf, Auguste Forestier en de al gepubliceerde Adolf Wölfli.

Te zien t/m zondag 25 augustus 2019

Het Outsider Art Museum laat verrassende, niet gepolijste kunst zien van mensen met een bijzondere achtergrond. Je stapt in een compleet nieuwe wereld en wordt meegenomen in de wilde achtbaan van deze kunstenaars, die soms bijna maniakaal te werk gaan. Hun werk is authentiek, tegendraads en onconventioneel. Het leert je op een andere manier naar kunst kijken.

Het Outsider Art Museum

Hermitage Amsterdam

Amstel 51

1018 DR Amsterdam

# Meer informatie via website outsiderartmuseum

Afbeelding: Art Brut: Joseph Degaudé-Lambert | Zonder titel | 18e eeuw | Gouache op papier | 20 x 29.5 cm | Fotografie Atelier de numérisation, Ville de Lausanne – Outsider Art Museum Amsterdam

• fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Art & Literature News, Art Brut, FDM Art Gallery, Outsider Art

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature