Fleurs du Mal Magazine

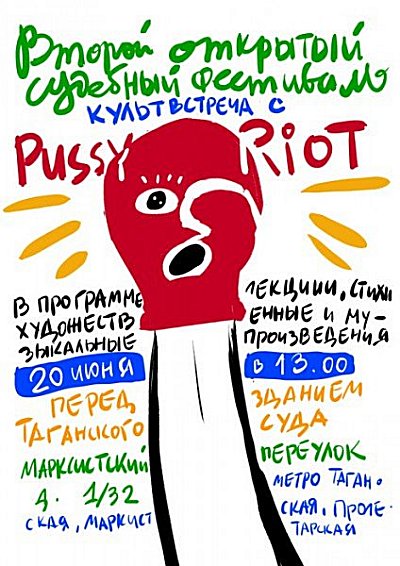

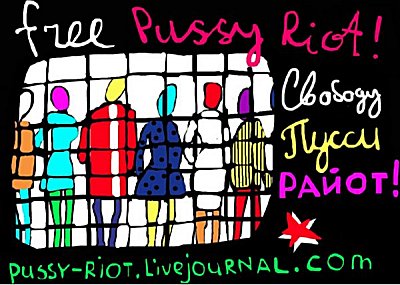

Russia urged to release ‘Pussy Riot’ group as court prolongs detention

A court in Moscow has ruled that three members of the female punk group Pussy Riot must remain in custody for six months after singing a protest song in Moscow’s main Orthodox church, prompting Amnesty International to reiterate its call for their immediate release.

Maria Alekhina, Ekaterina Samutsevich and Nadezhda Tolokonnikova, who are accused of “hooliganism on the grounds of religious hatred”, face possible prison sentences of up to seven years.

“These three activists have now been behind bars for months,awaiting a trial that should not be taking place, ” said Amnesty International Europe and Central Asia Programme Director John Dalhuisen.

“Even if the three arrested women did take part in the protest, the severity of the response of the Russian authorities and the detention on the serious criminal charge of hooliganism would not be a justifiable response to the peaceful – if, to many, offensive – expression of their political beliefs.”

The preliminary hearing of the case will continue next week, on 23 July.

Amnesty International considers the activists to be prisoners of conscience, detained solely for the peaceful expression of their beliefs.

“The Russian authorities must drop the charges of hooliganism and immediately and unconditionally release these three women, ” said Dalhuisen.

The protest song Virgin Mary, redeem us of Putin was performed in Christ the Saviour Cathedral in Moscow on 21 February 2012 by several members of the feminist Pussy Riot group with their faces covered in balaclavas.

The song calls on Virgin Mary to become a feminist and banish Vladimir Putin. It also criticises the dedication and support shown to Putin by some representatives of the Russian Orthodox Church.

It was one of a number of performances intended as a protest against Vladimir Putin in the run-up to Russia’s presidential elections in March.

The Russian authorities subsequently arrested Maria Alekhina and Nadezhda Tolokonnikova on 4 March and Ekaterina Samusevich on 15 March, claiming they were the masked singers.

One of the women, Nadezhda Tolokonnikova, admitted to being a member of the larger ‘Pussy Riot’ group and taking part in the protest while the other two deny any involvement in the cathedral protest.

Since its establishment in 2011, the Pussy Riot group has conducted several performances in public places such as the Moscow underground, Red Square and on the roofs of buses.

In media interviews the group members have stated that they protest against, among other things, stifling of freedom of expression and assembly in Russia, the unfair political process and the fabrication of criminal cases against opposition activists.

The European Court of Human Rights has repeatedly held that freedom of expression applies not only to inoffensive ideas, “but also to those that offend, shock or disturb the State or any sector of the population”.

“Even if the action was calculated to shock and was known to be likely to cause offence, the activists left the Cathedral when requested to do so and caused no damage,” said Dalhuisen.

“The entire action lasted only a few minutes and caused only minimal disruption to those using the Cathedral for other, notably religious, purposes.”

“The broader political context surrounding the anti-Putin protests at the time – and the anticlerical, anti-Putin content of the activists’ message (themselves unpunishable) – have clearly and unlawfully been taken into account in the charges that have been brought against them.”

A video montage of the song available on the internet has led to a wide debate about the protest. The press secretary of President-elect Vladimir Putin called the protest despicable and said it would be followed up “with all the necessary consequences”.

Although a representative of the Orthodox Church initially called for mercy for the protestors, subsequent statements by representatives of the Church have called for harsh punishment and for the women to be prosecuted for inciting hatred on grounds of religion. The women’s relatives have reportedly also received anonymous death threats.

≡ Website Amnesty International

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: MUSEUM OF PUBLIC PROTEST, REPRESSION OF WRITERS, JOURNALISTS & ARTISTS

Aquae sulis, Bath

Als een spiegelbeeld lijken de baden

de goden te willen behagen, zo strak

spannen zich deze aquae sulis naar boven.

Van marmer welhaast maar toch laat alles

wat zich zien wil zich hierin zien.

Inbreuk doet zelfs beweging ontstaan,

in steeds wijdere cirkels als zou zij

werkelijk slechts om water gaan.

Door de zachte heuvels hieromheen

glijdt zich de Avon. Bijna zeker

moet zij weten van de nevel die bij

avondval gaat hangen tussen beeld en spiegel.

Bert Bevers

(Verschenen in Hollands Maandblad, 29ste jaargang, nummer 481, Den Haag, 1987)

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive A-B, Bevers, Bert

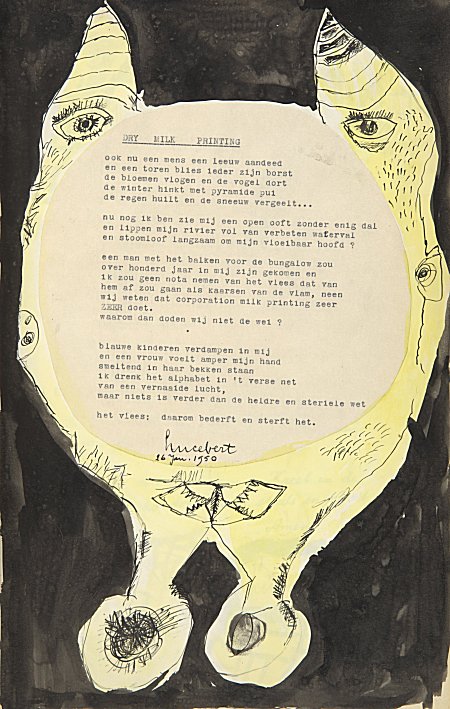

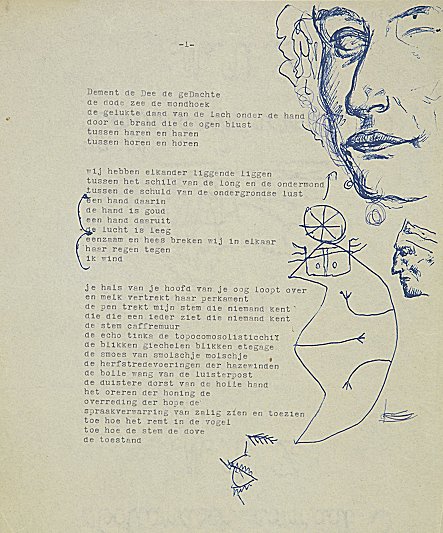

Cobra Museum Amstelveen

Open de kooien van de kunst:

gedichttekeningen van Lucebert

until 9 september 2012

Lucebert (1924-1994 – ps. van Lubertus Jacobus Swaanswijk) wordt gezien als een van Nederlands grootste kunstenaars. Hij was dichter, beeldend kunstenaar, fotograaf; ongekend veelzijdig en zeer productief. Als dichter speelde hij een vernieuwende rol in de revolutionaire literaire beweging de Vijftigers en als dubbeltalent in de Cobra-beweging die een doorbraak in de moderne kunst teweegbracht. Zijn beeldend werk en gedichten zijn verfrissend origineel, weerspiegelen actie en vitaliteit en zijn daardoor overrompelend actueel. Van alle moderne dichters had hij bovendien grote, misschien wel de grootste, invloed op onze taal.

Open de kooien van de kunst is gewijd aan een tot dusver nauwelijks belicht aspect van Luceberts oeuvre: de gedichttekeningen. In veel vroege gedichten van dichter-tekenaar Lucebert (1924-1994) is er een organische wisselwerking tussen de woorden van het gedicht en de spontaan gemaakte figuren in diverse technieken (van inkt en verf tot collages) in de marges of over het blad. Ook van een aantal latere gedichten bestaan varianten met een opzettelijke interactie met de beeldtaal. In zijn genre-overstijgende gedichttekeningen maakt Lucebert een fascinerende cross-over tussen woord en beeld, taal en kleur. Samensteller Erik Slagter bracht ruim vijfenzestig gedichttekeningen van Lucebert bijeen in Open de kooien van de kunst. In deze gedichttekeningen komt de veelzijdigheid van Luceberts vernieuwende woord- en beeldtaal prachtig tot uitdrukking. In de bibliografische beschrijving van deze gedichttekeningen geeft Erik Slagter dit aspect een plaats in het oeuvre van Lucebert.

Open de kooien van de kunst verschijnt ter gelegenheid van de gelijknamige tentoonstelling in het Cobra Museum in Amstelveen (8 mei- 9 september 2012). Paperback, 144 pagina’s, met ca. 80 (kleuren)afbeeldingen. ISBN: 978-90-77767-33-7 € 24,50

Lucebert, drukwerk voor anderen: Lucebert heeft, vooral in zijn vroege jaren, in opdracht en op verzoek tal van omslagontwerpen voor boeken van andere schrijvers gemaakt. Daarnaast tekende hij in de jaren vijftig regelmatig boek- en tijdschriftillustraties en maakte hij in later jaren tekeningen voor affiches van maatschappelijke instellingen.

Lucebert, drukwerk voor anderen bevat een overzicht van dit illustratieve werk. Vrijwel onvindbare tekeningen die Lucebert maakte voor bv. Het Parool en de Haagse post, worden met meer of minder bekende boekomslagen voor andere dichters en schrijvers (Campert, Kousbroek, Schierbeek e.v.a.) beschreven én afgebeeld. Paul van Capelleveen, conservator van de Koninklijke Bibliotheek, maakte een becommentarieerde en aantrekkelijk geschreven bibliografie van Luceberts drukwerk voor anderen, wonderschoon vormgegeven door Huug Schipper.

Lucebert, drukwerk voor anderen verschijnt ter gelegenheid van de tentoonstelling Open de kooien van de kunst in het Cobra Museum in Amstelveen (8 mei- 9 september 2012). In deze tentoonstelling worden ruim dertig illustraties getoond die Lucebert voor anderen heeft gemaakt. 144 pagina’s, met ca. 250 (kleuren)afbeeldingen. ISBN: 978-90-77767-35-1 € 24,50

Zolang de lijm niet loslaat: Tijdens een voordracht in 1951 presenteerde Lucebert (1924-1994) zich met een woordenboek (de Van Dale?) in de hand als ‘vandaal’ van de Nederlandse taal. Niettemin is bekend dat hij bij het schrijven van zijn poëzie vaak gebruikmaakte van woordenboeken.

Ruim een halve eeuw later wordt duidelijk dat Lucebert van alle moderne dichters misschien wel de grootste invloed op de hedendaagse taal heeft gehad. Het Nederlands heeft tal van gevleugelde woorden aan hem te danken en sommige van Luceberts taalscheppingen worden tot het bezonken talige erfgoed gerekend en staan inmiddels zelf in de Dikke Van Dale, zoals overal zanikt bagger en alles van waarde is weerloos. In Zolang de lijm niet loslaat bespreekt Ton den Boon (hoofdredacteur van de Dikke Van Dale) niet alleen Luceberts houding ten aanzien van het woordenboek, maar beschrijft hij bovendien de schatplichtigheid van het Nederlands aan deze grote dichter en laat hij zien hoe Lucebert in zijn gedichten woorden en uitdrukkingen heeft gecreëerd en/of herontdekt die vervolgens een eigen leven zijn gaan leiden in onze taal.

Zolang de lijm niet loslaat verschijnt mede naar aanleiding van de tentoonstelling Open de kooien van de kunst in het Cobra Museum in Amstelveen (8 mei- 9 september 2012).

72 pagina’s, met kleurenreproducties van enige niet eerder gepubliceerde tekeningen van Lucebert. ISBN: 978-90-77767-34-4 € 17,50

De drie de uitgaven zijn paperbacks met flappen (formaat 17 x 24) en vormen uit het oogpunt van hun vormgeving een kleine reeks.

De tentoonstelling Open de kooien van de kunst in het Cobra Museum: Luceberts gedichttekeningen uit de periode 1949-1994 zijn verrassend veelzijdig in woord- en beeldtaal. Ook de expositie is daarom veelzijdig van opzet. Zo komt er een dichterskooi geïnspireerd op de ‘dichterskooi’ waarin de literaire experimentelen zich in november 1949 in het Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam verschansten. Behalve de gedichttekeningen worden liber amicora getoond (unica gemaakt voor vrienden), alsmede het gedrukte grafische werk dat voor anderen ontstond. Voorts wordt een aantal originele boekjes uit de collectie van het Stedelijk, die in het najaar 2011 door uitgeverij De Bezige Bij in facsimile zijn uitgebracht, getoond. Behalve het Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam zijn het Goethe-Instituut Nederland, Karel Appel Foundation en de erven Lucebert belangrijke bruikleengevers. Het Letterkundig Museum uit Den Haag draagt bij met documentatie. De tentoonstelling is een initiatief van kunsthistoricus en auteur Erik Slagter.

Cobra Museum Amstelveen

Open de kooien van de kunst:

gedichttekeningen van Lucebert

until 9 september 2012

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive K-L, Archive K-L, Art & Literature News, FDM Art Gallery, Lucebert, Lucebert

William Shakespeare

(1564-1616)

THE SONNETS

Sonnet 137

Thou blind fool Love, what dost thou to mine eyes,

That they behold and see not what they see?

They know what beauty is, see where it lies,

Yet what the best is, take the worst to be.

If eyes corrupt by over-partial looks,

Be anchored in the bay where all men ride,

Why of eyes’ falsehood hast thou forged hooks,

Whereto the judgment of my heart is tied?

Why should my heart think that a several plot,

Which my heart knows the wide world’s common place?

Or mine eyes seeing this, say this is not

To put fair truth upon so foul a face?

In things right true my heart and eyes have erred,

And to this false plague are they now transferred.

![]()

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: -Shakespeare Sonnets

Hélène Swarth

(1859-1941)

Liefde

I

En langs een wand van rotsen, rug aan rug,

Volgde ik een pad verlicht door maan noch zon.

Toen stond ik vóór een afgrond en ik kon

Geen handbreed verder en geen stap terug.

En de angst des doods kwam over me, ik begon

Te beven en ik riep: – ‘Wie bouwt me een brug?’

En ‘t ver gebergte gaf mij, hoonend-stug,

Mijn woorden weêr, tot wanhoop mij verwon.

Toen zag ik naast me een marmerbleek gelaat,

Met donkere oogen, vonklende in den nacht,

En ‘k hoorde een stem, gebiedend, schoon zeer zacht:

‘Zoo ge om mijn hals vertrouwend de armen slaat,

Draag ík u over de’ afgrond!’ – Ik dan, als

Een kind, sloeg de armen, zwijgend, om zijn hals.

II

Ik hoorde ‘t ruischen van zijn vleugelslag

En anders niet. Toen vroeg ik: – ‘Wie zijt gij?

‘k Voel me aan uw borst zóó veilig en zóó blij,

Als hadde ik niet geleefd vóór dezen dag.’

Maar zwijgend vloog hij voort naar de andre zij

Van de’ afgrond, en ik weende om wat ik zag:

De weemoedswel, die in zijne oogen lag,

Vloeide over. – ‘Engel, is die traan voor mij?’

En na een wijle sprak hij: – ‘Ja, ik ween

Om wat ge in mijn naam lijden moest weleer,

En wéér moet lijden. Zie, hier blijft ge alleen.’

En in een woud liet hij met mij zich nêer,

Sloot met een kus mijne oogen en… vloog heen.

En ‘k zeeg ter aarde en hoorde en zag niet meer.

Hélène Swarth poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Swarth, Hélène

Matthew Arnold

(1822 – 1888)

The Last Word

Creep into thy narrow bed,

Creep, and let no more be said!

Vain thy onset! all stands fast.

Thou thyself must break at last.

Let the long contention cease!

Geese are swans, and swans are geese.

Let them have it how they will!

Thou art tired: best be still.

They out-talked thee, hissed thee, tore thee?

Better men fared thus before thee;

Fired their ringing shot and passed,

Hotly charged – and sank at last.

Charge once more, then, and be dumb!

Let the victors, when they come,

When the forts of folly fall,

Find thy body by the wall!

Matthew Arnold poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive A-B

Nick J. Swarth

Nou, ik ga eens pleite, ajuus

Het grauw uit Wedding treurt om het vertrek

van de Brave Bankier Zwijk. Men kijkt bleek

uit de ogen

krabt zich de donkere wallen

de dun

behaarde dameskop of dreigt om te vallen van

verdriet.

Hassan zit te bellen

steeds te bellen en BULKT

in zijn mobiel

HASSAN! HASSAN schrei nicht so!

Dit zijn beelden bij een crisis.

We doen wat boodschappen, maar kunnen ons

niet zetten tot ruigere activiteiten

dus geen baldadige middernachtelijke escapades

al zijn we geboend

geschoren

en gekleed om een

haai te doden

HASSAN schrei nicht so!

De herfst daalt in agent van klompjes stompjes

en klamme pit.

JA dat zijn TANDEN en NEE het is niet FRAAI

daar in de bek van de haai meer gat dan gebit.

Je zegt dat je nog even een blokje om gaat.

Er ontstaat een SKELET

het kakelt en orakelt en voert het hoogste woord

ik heb het eindelijk gedaan DAT HELE STUK

gelopen naar de maan.

(uit: Nick J. Swarth: MIJN ONSTERFELIJKE LEVER. Gedichten & tekeningen. Uitgeverij IJzer, Utrecht | 2012. ISBN 978 90 8684 086 1 – NUR 305 – Paperback, 64 blz. Prijs: € 10 – Zie voor meer informatie: www.swarth.nl )

Nick J. Swarth poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: Archive S-T, Swarth, Nick J.

Ernst Stadler

(1883-1914)

Pans Trauer

Die dunkle Trauer, die um aller Dinge Stirnen todessüchtig wittert,

Hebt sachte deiner Flöte Klingen auf, das mittäglich im braunen Haideröhricht zittert.

Die Schwermut aller Blumen, aller Gräser, Steine, Schilfe, Bäume stummes Klagen

Saugt es in sich und will sie demutsvoll in blaue Sommerhimmel tragen.

Die Müdigkeit der Stunden, wenn der Tag durch gelbe Dämmernebel raucht,

Heimströmend alles Licht im mütterlichen Schoß der Nacht sich untertaucht,

Verlorne Wehmut kleiner Lieder, die ein Mädchen tanzend sich auf Sommerwiesen singt,

Glockengeläut, das heimwehrauschend über sonnenrote Abendhügel dringt,

Die große Traurigkeit des Meers, das sich an grauer Küsten Damm die Brust zerschlägt

Und auf gebeugtem Rücken endlos die Vergänglichkeit vom Sommer in den jungen Frühling trägt –

Sinkt in dein Spiel, schwermütig helle Blüte, die in dunkle Brunnen glitt . . .

Und alle stummen Dinge sprechen leise glühend ihrer Seelen wehste Litaneien mit.

Du aber lächelst, lächelst . . Deine Augen beugen sich vergessen, weltenweit entrückt

Über die Tiefen, draus dein Rohr die große Wunderblume pflückt.

1911

Ernst Stadler poetry

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: *War Poetry Archive, - Archive Tombeau de la jeunesse, Archive S-T, Archive S-T, Stadler, Ernst

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (25)

Shoot! (Si Gira, 1926). The Notebooks of Serafino Gubbio, Cinematograph Operator by Luigi Pirandello. Translated from the Italian by C. K. Scott Moncrieff

BOOK V

3

I have laid these notes aside for some days.

They have been days of sorrow and trepidation. They are still not quite over; but now the storm, which broke with terrific force in the soul of this unhappy man whom all of us here have vied with one another in helping compassionately and with all the more devotion in that he was virtually a stranger to us all and what little we knew of him combined with his appearance and the suggestion of fatality that he conveyed to inspire in us pity and a keen interest in his most wretched plight; this storm, I say, seems to be shewing signs of gradually abating. Unless it is only a brief lull. I fear it. Often, at the height of a gale, a formidable peal of thunder succeeds in clearing the sky for a little, but presently the mass of clouds, rent asunder for a moment, return to accumulate slowly and ever more menacingly, and the gale having increased its strength breaks out afresh, more furious than before. The calm, in fact, in which Nuti’s spirit seems gradually to be gathering strength after his delirious ravings and the horrible frenzy of all these days, is tremendously dark, just like the calm of a sky in which a storm is gathering.

No one takes any notice, or seems to take any notice of this, perhaps from the need which we all feel to heave a momentary sigh of relief, saying that in any case the worst is over. We ought, we intend to adjust first, to the best of our ability, ourselves, and also everything round us, swept by the whirlwind of his madness; because there remains not only in all of us but even in the room, in the very furniture of the room, a sort of blind stupefaction, a strange uncertainty in the appearance of everything, as it were an air of hostility, suspended and diffused.

In vain do we detach ourselves from the outburst of a soul which from its profoundest depths hurls forth, broken and disordered, the most recondite thoughts, never yet confessed to itself even, its most serious and awful feelings, the strangest sensations which strip things of every familiar meaning, to give them at once another, unexpected meaning, with a truth that springs forth and imposes itself, disconcerting and terrifying. The terror is due to our recognition, with an appalling clarity, that madness dwells and lurks within each of us and that a mere trifle may let it loose: release it for a moment from the elastic web of present consciousness, and lo, all the imaginings accumulated in years past and now wandering unconnected; the fragments of a life that has remained hidden, because we could not or would not let it be reflected in ourselves by the light of reason; dubious actions, shameful falsehoods, dark hatreds, crimes meditated in the shadow of our inward selves and planned to the last detail, and forgotten memories and unconfessed desires burst in tumultuous, with diabolical fury, roaring like wild beasts. On more than one occasion, we all looked at one another with madness in our eyes, the terror of the spectacle of that madman being sufficient to release in us too for a moment the elastic net of consciousness. And even now we eye askance, and go up and touch with a sense of misgiving some object in the room which was for a moment illumined with the sinister light of a new and terrible meaning by the sick man’s hallucinations; and, going to our own rooms, observe with stupefaction and repugnance that… yes, positively, we too have been overborne by that madness, even at a distance, even when alone: we find here and there clear signs of it, pieces of furniture, all sorts of things, strangely out of place.

We ought, we intend to adjust ourselves, we need to believe that the patient is now in this state, in this brooding calm, because he is still stunned by the violence of his final outbursts and is now exhausted, worn out.

There suffices to support this deception a slight smile of gratitude which he just perceptibly offers with his lips or eyes to Signorina Luisetta: a breath, an imperceptible glimmer which does not, in my opinion, emanate from the sick man, but is rather suffused over his face by his gentle nurse, whenever she draws near and bends over the bed.

Alas, how she too is worn out, his gentle nurse! But no one gives her a thought; least of all herself. And yet the same storm has torn up and swept away this innocent creature!

It has been an agony of which as yet perhaps not even she can form any idea, because she still perhaps has not with her, within her, her own soul. She has given it to him, as a thing not her own, as a thing which he in his delirium might appropriate to derive from it refreshment and comfort.

I have been present at this agony. I have done nothing, nor could I perhaps have done anything to prevent it. But I see and confess that I am revolted by it. Which means that my feelings are compromised. Indeed, I fear that presently I may have to make another painful confession to myself.

This is what has happened: Nuti, in his delirium, mistook Signorina Luisetta for Duccella and, at first, inveighed furiously against her, shouting in her face that her obduracy, her cruelty to him were unjust, since he was in no way to blame for the death of her brother, who, of his own accord, like an idiot, like a madman, had killed himself for that woman; then, as soon as she, overcoming her first terror, grasping at once the nature of his hallucination, went compassionately to his side, lie refused to let her leave him for a moment, clasped her tightly to him, sobbing broken-heartedly or murmuring the most burning, the tenderest words of love to her, and caressing her or kissing her hands, her hair, her brow.

And she allowed him to do it. And all the rest of us allowed it. Because those words, those caresses, those embraces, those kisses were not intended for her: they were for a hallucination, in which his delirium found peace. And so we had to allow him. She, Signorina Luisetta, made her heart pitiful and loving for another girl’s sake; and this heart, thus made pitiful and loving, she gave to him, as a thing not her own, but belonging to that other girl, to Duccella. And while he appropriated that heart, she could not, must not appropriate those words, those caresses, those kisses…. But she trembled at them in every fibre of her body, poor child, ready from the first moment to feel such pity for this man who was suffering so on account of the other woman. And not on her own behalf, who did really pity him, did it come to her to feel pitiful, but for that other, whom she naturally supposes to be harsh and cruel. Well, she has given her pity to the other, that the other might pass it on to him, and by him–through the medium of Luisetta’s body–be loved and caressed in return. But love, love, who has given that? It was she that had to give it, to give love, together with her pity. And the poor child has given it. She knows, she feels that she has given it, with all her soul, with all her heart; and at the same time she must suppose that she has given it for the other.

The result has been as follows: that while he, now, is gradually returning to himself and collecting himself, and shutting himself up again darkly in his trouble; she remains empty and lost, held in suspense, without a gleam in her eye, as though she had lost her wits, a ghost, the ghost that entered into his hallucination. For him, the ghost has vanished, and with the ghost, love. But this poor child who has emptied herself to fill that ghost with herself, her love, her pity, is now herself left a ghost; and he notices nothing. He barely smiles at her in gratitude. The remedy has proved effective: the hallucination has vanished: nothing more at present, is that it?

I should not be so distressed, had I not, for all these days, seen myself obliged to bestow my pity, also, to spend myself, to run in all directions, to sit up for several nights in succession, not from a feeling that was genuinely my own, that is to say one inspired in me by Nuti, as I could have wished; but from a different feeling, one of pity indeed, but of interested pity, so interested that it made and still makes appear false and odious to me the pity which I she-wed and am still shewing for Nuti.

I feel that, as a witness of the sacrifice (without doubt involuntary) which he has made of Signorina Luisetta’s heart, I, who seek to obey my true feelings, ought to have withdrawn my pity from him. I did indeed withdraw it inwardly, to pour it all upon that poor, tormented little heart, but I continued to shew pity for him, seeing that I could do no less, compelled by her sacrifice, which was even greater. If she actually subjected herself to that torture ‘out of pity’ for him, could I, could the rest of us shrink from devotion, fatigue, proofs of Christian charity that were far less? For me to draw back meant my admitting and letting it be seen that she was undergoing this torture not ‘out of pity only’, but also ‘for love’ of him, indeed principally ‘for love’. And that could not, must not be. I have had to pretend, because she has had to believe that she was bestowing her love upon him for that other woman. And I have pretended, albeit with self-contempt, marvellously. Only in this way have I been able to modify her attitude towards myself; to make her my friend again. And yet, by shewing myself for her sake so compassionate towards Nuti, I have perhaps lost the one way that remained to me of calling her back to herself; that, namely, of proving to her that Duccella, on whose behalf she imagines that she loves him, has no reason whatever to feel any pity for him. Were I to give Duccella her true shape, her ghost, that loving and pitiful ghost, into which she, Signorina Luisetta, has transformed herself, would have to vanish, and leave her, SignorinaLuisetta, with her love ‘unjustified’ and in no way sought by him: because he has sought it from the other, not from her, and she has given it to him for the other, and not for herself, thus publicly, before us all.

Very good, but if I know that she has really given it to him, beneath this pious fiction of pity, upon which I am now weaving sophistries?

As Aldo Nuti thinks Duccella hard and cruel, so she would think me hard and cruel, were I to tear from her the veil of this pious fiction. She is a sham Duccella, simply because she is in love; and she knows that the true Duccella has not the slightest reason to be in love; she knows it from the very fact that Aldo Nuti, now that his hallucination has passed, no longer sees any sign of love in her, and sadly just thanks her for her pity.

Perhaps, at the cost of suffering a little more, she might cover herself, but only on condition that Duccella became really pitiful, upon learning the wretched plight to which her former sweetheart had been brought, and appeared in person here, by the bed upon which he lies, to give him her love again and so to save him. But Duccella will not come. And Signorina Luisetta will continue to pretend to all of us and also to herself, in good faith, that it is for her sake that she is in love with Aldo Nuti.

Luigi Pirandello: Shoot! (25)

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: -Shoot!

Christine de Pisan

(ca. 1364-1430)

Helas! le trés mauvais songe

Helas! le trés mauvais songe

Que j’ay ceste nuit songé,

Fait que mon cuer toudis songe.

Oncques ne retint esponge

Mieulx chose, certes, que j’é,

Helas! le trés mauvais songe.

Mais ne me dit chose dont je

Doye esperer que congié;

Dieux doint que ce soit mençonge,

Helas! le trés mauvais songe.

Christine de Pisan poetry

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Archive O-P, Pisan, Christine de

William Shakespeare

(1564-1616)

THE SONNETS

Sonnet 136

If thy soul check thee that I come so near,

Swear to thy blind soul that I was thy ‘Will’,

And will thy soul knows is admitted there,

Thus far for love, my love-suit sweet fulfil.

‘Will’, will fulfil the treasure of thy love,

Ay, fill it full with wills, and my will one,

In things of great receipt with case we prove,

Among a number one is reckoned none.

Then in the number let me pass untold,

Though in thy store’s account I one must be,

For nothing hold me, so it please thee hold,

That nothing me, a something sweet to thee.

Make but my name thy love, and love that still,

And then thou lov’st me for my name is Will.

![]()

kempis.nl poetry magazine

More in: -Shakespeare Sonnets

J.A. Woolf: Making memories (19)

kempis.nl poetry magazine 2012

More in: J.A. Woolf

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature