Fleurs du Mal Magazine

.jpg)

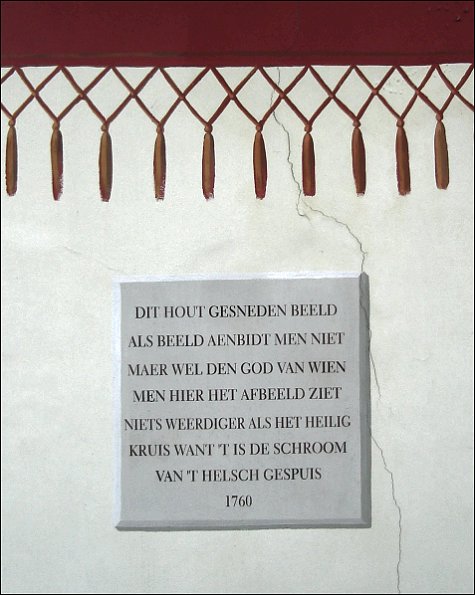

HISTORIA BELGICA

Belgian Landscapes 2

Photos Kempis

© kemp=mag – magazine for art & literature

More in: Historia Belgica

.jpg)

B e n J o n s o n

(1572-1637)

To the memory of

my beloved master

William Shakespeare,

and what he hath left us

To draw no envy, Shakspeare, on thy name,

Am I thus ample to thy book and fame;

While I confess thy writings to be such,

As neither man, nor muse can praise too much.

’Tis true, and all men’s suffrage. But these ways

Were not the paths I meant unto thy praise;

For silliest ignorance on these may light,

Which, when it sounds at best, but echoes right;

Or blind affection, which doth ne’er advance

The truth, but gropes, and urgeth all by chance;

Or crafty malice might pretend this praise,

And think to ruin, where it seemed to raise.

These are, as some infamous bawd, or whore,

Should praise a matron; what would hurt her more?

But thou art proof against them, and, indeed,

Above the ill-fortune of them, or the need.

I, therefore, will begin: Soul of the age!

The applause! delight! and wonder of our stage!

My Shakspeare rise! I will not lodge thee by

Chaucer, or Spenser, or bid Beaumont lie

A little further off, to make thee room:

Thou art a monument without a tomb,

And art alive still, while thy book doth live

And we have wits to read, and praise to give.

That I not mix thee so, my brain excuses,

I mean with great, but disproportioned Muses;

For if I thought my judgment were of years,

I should commit thee surely with thy peers,

And tell how far thou didst our Lily outshine,

Or sporting Kyd, or Marlow’s mighty line.

And though thou hadst small Latin and less Greek,

From thence to honour thee, I will not seek

For names: but call forth thundering Eschylus,

Euripides, and Sophocles to us,

Pacuvius, Accius, him of Cordoua dead,

To live again, to hear thy buskin tread,

And shake a stage; or, when thy socks were on,

Leave thee alone for the comparison

Of all that insolent Greece, or haughty Rome

Sent forth, or since did from their ashes come.

Triumph, my Britain, thou hast one to show,

To whom all scenes of Europe homage owe.

He was not of an age, but for all time!

And all the Muses still were in their prime,

When, like Apollo, he came forth to warm

Our ears, or like a Mercury to charm!

Nature herself was proud of his designs,

And joyed to wear the dressing of his lines!

Which were so richly spun, and woven so fit,

As, since, she will vouchsafe no other wit.

The merry Greek, tart Aristophanes,

Neat Terence, witty Plautus, now not please;

But antiquated and deserted lie,

As they were not of nature’s family.

Yet must I not give nature all; thy art,

My gentle Shakspeare, must enjoy a part.

For though the poet’s matter nature be,

His heart doth give the fashion: and, that he

Who casts to write a living line, must sweat,

(Such as thine are) and strike the second heat

Upon the Muse’s anvil; turn the same,

And himself with it, that he thinks to frame;

Or for the laurel, he may gain a scorn;

For a good poet’s made, as well as born.

And such wert thou! Look how the father’s face

Lives in his issue, even so the race

Of Shakspeare’s mind and manners brightly shines

In his well-turnèd, and true filèd lines;

In each of which he seems to shake a lance,

As brandished at the eyes of ignorance.

Sweet Swan of Avon! what a sight it were

To see thee in our water yet appear,

And make those flights upon the banks of Thames,

That so did take Eliza, and our James!

But stay, I see thee in the hemisphere

Advanced, and made a constellation there!

Shine forth, thou star of poets, and with rage,

Or influence, chide, or cheer the drooping stage,

Which, since thy flight from hence, hath mourned like night,

And despairs day, but for thy volume’s light.

Poem of the week – November 30, 2008

kemp=mag poetry magazine

More in: Archive I-J, Shakespeare, William

![]()

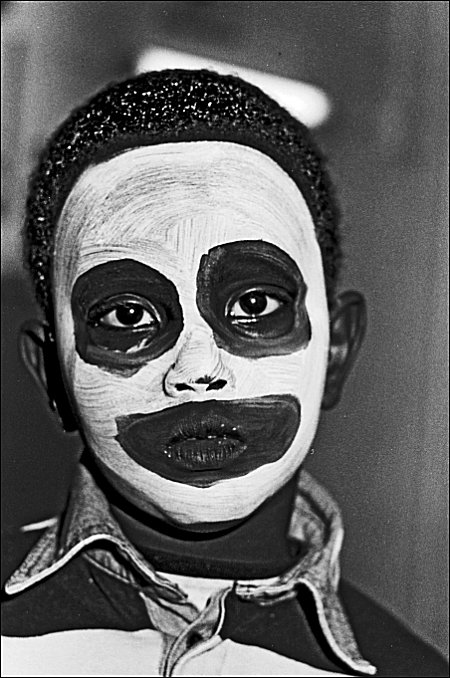

D E H E K S

is nog volop levend

Walter Breedveld over Jacques Sinninghe

door Jef van Kempen

Walter Breedveld (1901-1977) was lange tijd ongekend populair als schrijver van Brabantse volksboeken. Maar Breedveld deed meer. Zo maakte hij in 1959 en 1960 ruim vijftig portretten van Brabantse kunstenaars voor De Gelderlander. Een korte serie belicht deze andere kant van Breedveld. Vandaag: Jacques R.W. Sinninghe (1904-1988).

Jacques Rudolph Willem Sinninghe werd in Roermond geboren, maar kwam al op zijn vierde jaar in Breda terecht. Zijn vader was er directeur van het postkantoor. Jacques Sinninghe zou de stad Breda zijn hele leven trouw blijven.

Aan Breedveld legde Sinninghe het verschil uit in geaardheid tussen het volk van West- en van Oost-Brabant: “West-Brabant is agressiever, dynamischer. In hun volksverhalen komen veel meer moorden voor, verkrachtingen, afpersingen en ontsporingen dan in Oost-Brabant.”

Walter Breedveld: “Hij is een typisch voorbeeld van een allochtone Brabander, die in de loop van de jaren volkomen met Brabant is vergroeid en toch niet-Brabantse eigenheden heeft behouden; men ziet het aan sommige gewoonten en hoort het aan enkele klanken en woordvormen.”

Jacques Sinninghe studeerde aan de Economische Hogeschool in Rotterdam. Na zijn studietijd zwierf hij een aantal jaren rond in Zuid-Europa, waar hij gefascineerd raakte door de volksverhalen die hij daar hoorde. Terug in Nederland besloot hij in de journalistiek te gaan en van het verzamelen van volksverhalen zijn beroep te maken. Hij ging met “zijn tape-recorder den boer op”, zoals Breedveld het uitdrukte. Uiteindelijk zou Sinninghe alleen al in Nederland en Vlaanderen zo’n 45.000 mythen, sagen en legendes optekenen. Met de tientallen boeken en duizenden artikelen die hij schreef, verwierf hij internationale roem. Hij was de eerste ter wereld, die een sagen- en legendencatalogus samenstelde.

“Hij schrijft voortreffelijk proza, ondanks de beperkingen waaraan hij noodzakelijk is gebonden. In zijn genre is hij zeker een kunstenaar.” Breedveld gaat verder: “De menselijke psyche te leren kennen in al haar aspecten is een hartstocht geworden. (…) De mens is zonder twijfel het merkwaardigste levende wezen op aarde, zijn belangrijkheid stijgt ver uit boven de fauna en de flora en boven de dingen der dode stof. (…) Jacques Sinninghe gaat zozeer in zijn werk op dat hij niet veel aandacht meer heeft voor andere dingen. De problematiek van onze om inzicht worstelende tijd ontgaat niet aan zijn intelligentie, maar hij kan er zich niet druk over maken. Zijn vak heeft zijn ganse liefde, zijn hele persoon; hij kan er niet over uitgepraat komen. (…) Het bijgeloof is nog zeer sterk, de heks is nog volop levend in de volksverbeelding. Zij is nog steeds een kwaadaardig wezen met toverkracht begaafd.”

De bibliotheek en de verzameling volksverhalen van Jacques R.W. Sinninghe werden na zijn dood ondergebracht in de Brabant-collectie van de KUB.

(Brabants Dagblad 18 oktober 2001)

Jef van Kempen:

De heks is nog volop levend

Walter Breedveld over Jacques sinninghe

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Brabantia Nostra, Jef van Kempen, Walter Breedveld

.jpg)

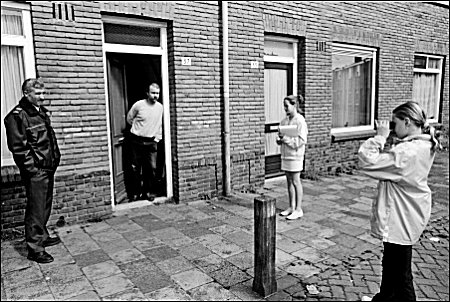

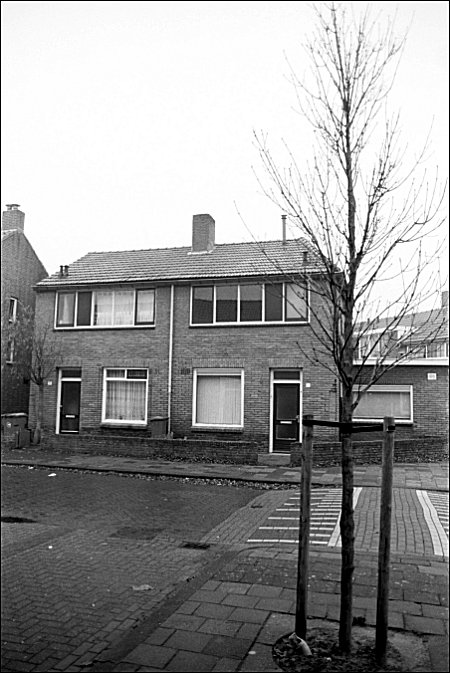

Harrie Janssens & Jef van Kempen

Het gevoel dat je hier thuishoort

Een geschiedenis van de Trouwlaan,

Zeehelden- en Uitvindersbuurt in Tilburg

Livius Boekhandel Tilburg

ISBN 90-807430-2-X

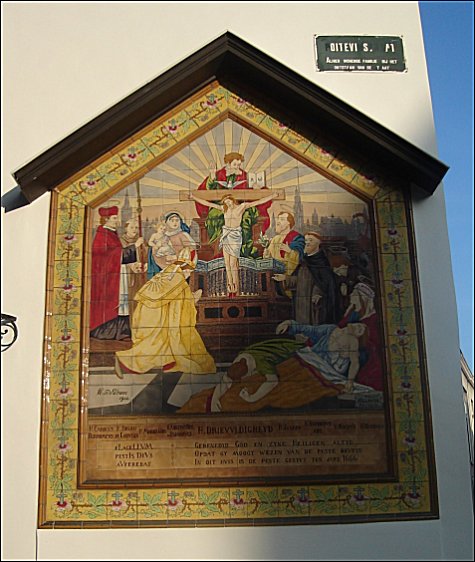

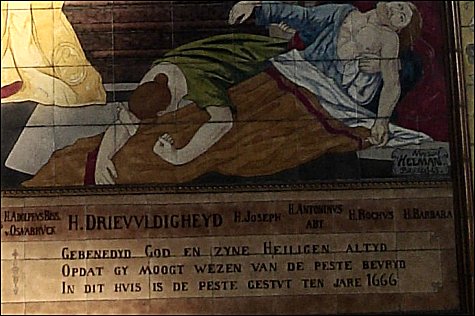

.jpg)

kemp=mag poetry magazine

More in: Harrie Janssens Photos, OLV van de Veestraat

![]()

Museum of Lost Concepts

Disclosure 16-20

(1968-2008)

jef van kempen © fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: *Concrete + Visual Poetry K-O, Conceptual writing, FLUXUS LEGACY, Kempen, Jef van, Visual & Concrete Poetry, ZERO art

.jpg)

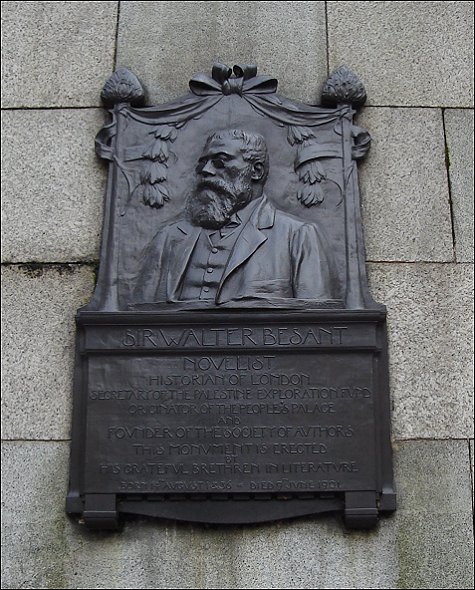

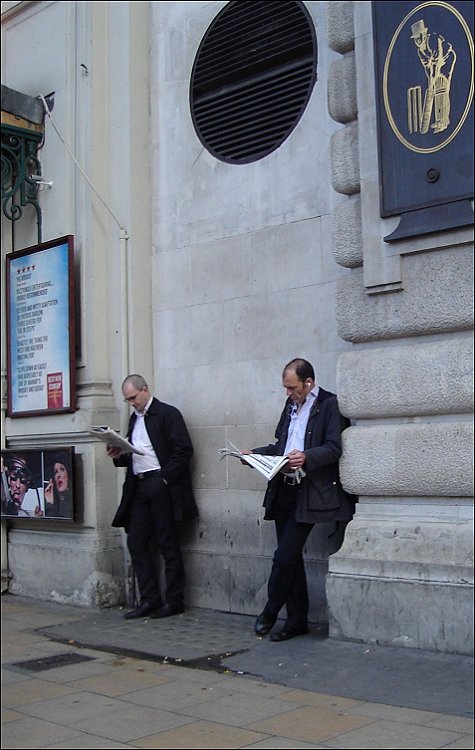

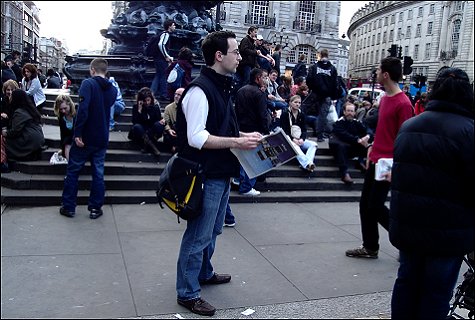

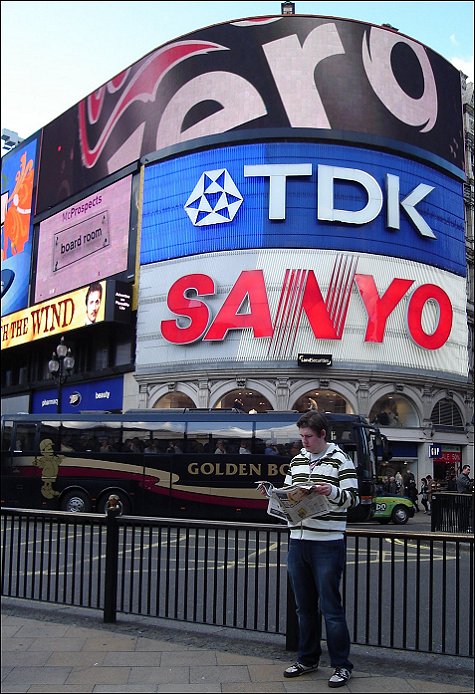

R E A D I N G L O N D O N 4

KEMP=MAG IN LONDON

Reading London part 4

kemp=mag poetry magazine – photos Kempis

More in: FDM in London

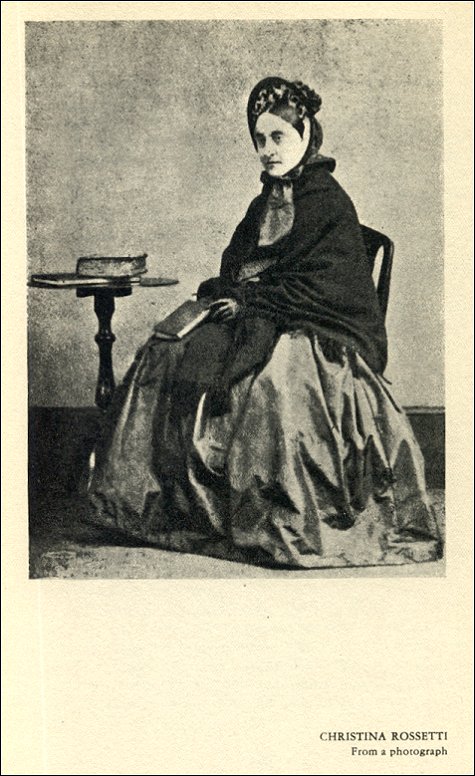

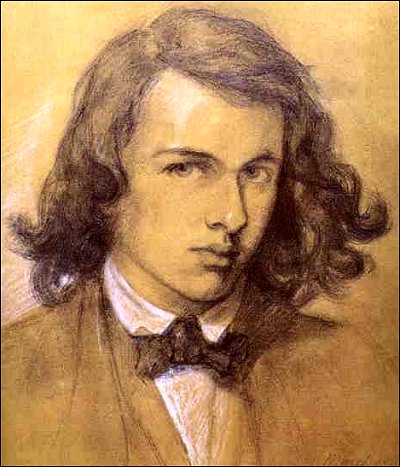

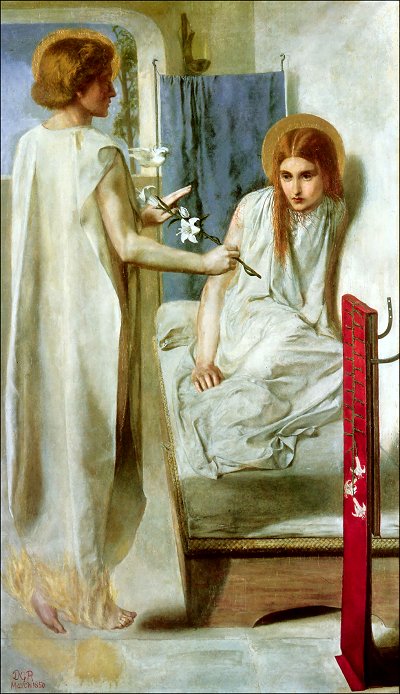

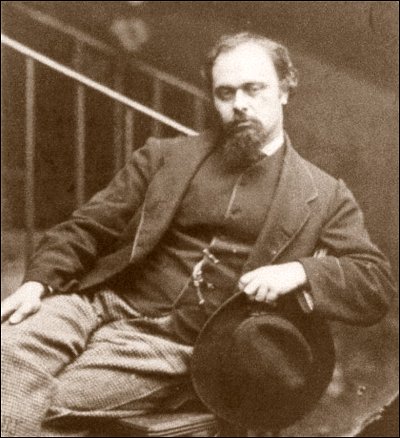

D a n t e G a b r i e l R o s s e t t i

(1828-1882)

S e v e n P o e m s

Insomnia

Thin are the night-skirts left behind

By daybreak hours that onward creep,

And thin, alas! the shred of sleep

That wavers with the spirit’s wind:

But in half-dreams that shift and roll

And still remember and forget,

My soul this hour has drawn your soul

A little nearer yet.

Our lives, most dear, are never near,

Our thoughts are never far apart,

Though all that draws us heart to heart

Seems fainter now and now more clear.

To-night Love claims his full control,

And with desire and with regret

My soul this hour has drawn your soul

A little nearer yet.

Is there a home where heavy earth

Melts to bright air that breathes no pain,

Where water leaves no thirst again

And springing fire is Love’s new birth?

If faith long bound to one true goal

May there at length its hope beget,

My soul that hour shall draw your soul

For ever nearer yet.

The Portrait

This is her picture as she was:

It seems a thing to wonder on,

As though mine image in the glass

Should tarry when myself am gone.

I gaze until she seems to stir,–

Until mine eyes almost aver

That now, even now, the sweet lips part

To breathe the words of the sweet heart:–

And yet the earth is over her.

Alas! even such the thin-drawn ray

That makes the prison-depths more rude,–

The drip of water night and day

Giving a tongue to solitude.

Yet only this, of love’s whole prize,

Remains; save what in mournful guise

Takes counsel with my soul alone,–

Save what is secret and unknown,

Below the earth, above the skies.

In painting her I shrin’d her face

Mid mystic trees, where light falls in

Hardly at all; a covert place

Where you might think to find a din

Of doubtful talk, and a live flame

Wandering, and many a shape whose name

Not itself knoweth, and old dew,

And your own footsteps meeting you,

And all things going as they came.

A deep dim wood; and there she stands

As in that wood that day: for so

Was the still movement of her hands

And such the pure line’s gracious flow.

And passing fair the type must seem,

Unknown the presence and the dream.

‘Tis she: though of herself, alas!

Less than her shadow on the grass

Or than her image in the stream.

That day we met there, I and she

One with the other all alone;

And we were blithe; yet memory

Saddens those hours, as when the moon

Looks upon daylight. And with her

I stoop’d to drink the spring-water,

Athirst where other waters sprang;

And where the echo is, she sang,–

My soul another echo there.

But when that hour my soul won strength

For words whose silence wastes and kills,

Dull raindrops smote us, and at length

Thunder’d the heat within the hills.

That eve I spoke those words again

Beside the pelted window-pane;

And there she hearken’d what I said,

With under-glances that survey’d

The empty pastures blind with rain.

Next day the memories of these things,

Like leaves through which a bird has flown,

Still vibrated with Love’s warm wings;

Till I must make them all my own

And paint this picture. So, ‘twixt ease

Of talk and sweet long silences,

She stood among the plants in bloom

At windows of a summer room,

To feign the shadow of the trees.

And as I wrought, while all above

And all around was fragrant air,

In the sick burthen of my love

It seem’d each sun-thrill’d blossom there

Beat like a heart among the leaves.

O heart that never beats nor heaves,

In that one darkness lying still,

What now to thee my love’s great will

Or the fine web the sunshine weaves?

For now doth daylight disavow

Those days,–nought left to see or hear.

Only in solemn whispers now

At night-time these things reach mine ear;

When the leaf-shadows at a breath

Shrink in the road, and all the heath,

Forest and water, far and wide,

In limpid starlight glorified,

Lie like the mystery of death.

Last night at last I could have slept,

And yet delay’d my sleep till dawn,

Still wandering. Then it was I wept:

For unawares I came upon

Those glades where once she walk’d with me:

And as I stood there suddenly,

All wan with traversing the night,

Upon the desolate verge of light

Yearn’d loud the iron-bosom’d sea.

Even so, where Heaven holds breath and hears

The beating heart of Love’s own breast,–

Where round the secret of all spheres

All angels lay their wings to rest,–

How shall my soul stand rapt and aw’d,

When, by the new birth borne abroad

Throughout the music of the suns,

It enters in her soul at once

And knows the silence there for God!

Here with her face doth memory sit

Meanwhile, and wait the day’s decline,

Till other eyes shall look from it,

Eyes of the spirit’s Palestine,

Even than the old gaze tenderer:

While hopes and aims long lost with her

Stand round her image side by side,

Like tombs of pilgrims that have died

About the Holy Sepulchre.

The Kiss

What smouldering senses in death’s sick delay

Or seizure of malign vicissitude

Can rob this body of honour, or denude

This soul of wedding-raiment worn to-day?

For lo! even now my lady’s lips did play

With these my lips such consonant interlude

As laurelled Orpheus longed for when he wooed

The half-drawn hungering face with that last lay.

I was a child beneath her touch, — a man

When breast to breast we clung, even I and she, —

A spirit when her spirit looked through me, —

A god when all our life-breath met to fan

Our life-blood, till love’s emulous ardours ran,

Fire within fire, desire in deity.

Through Death To Love

Like labour-laden moonclouds faint to flee

From winds that sweep the winter-bitten wold,–

Like multiform circumfluence manifold

Of night’s flood-tide,–like terrors that agree

Of hoarse-tongued fire and inarticulate sea,–

Even such, within some glass dimm’d by our breath,

Our hearts discern wild images of Death,

Shadows and shoals that edge eternity.

Howbeit athwart Death’s imminent shade doth soar

One Power, than flow of stream or flight of dove

Sweeter to glide around, to brood above.

Tell me, my heart,–what angel-greeted door

Or threshold of wing-winnow’d threshing-floor

Hath guest fire-fledg’d as thine, whose lord is Love?

The Gloom that Breathes Upon Me

The gloom that breathes upon me with these airs

Is like the drops which stike the traveller’s brow

Who knows not, darkling, if they bring him now

Fresh storm, or be old rain the covert bears.

Ah! bodes this hour some harvest of new tares,

Or hath but memory of the day whose plough

Sowed hunger once, — the night at length when thou,

O prayer found vain, didst fall from out my prayers?

How prickly were the growths which yet how smooth,

Along the hedgerows of this journey shed,

Lie by Time’s grace till night and sleep may soothe!

Even as the thisteldown from pathsides dead

Gleaned by a girl in autumns of her youth,

Which one new year makes soft her marriage-bed.

The Ballad of Dead Ladies

Tell me now in what hidden way is

Lady Flora the lovely Roman?

Where’s Hipparchia, and where is Thais,

Neither of them the fairer woman?

Where is Echo, beheld of no man,

Only heard on river and mere–

She whose beauty was more than human?–

But where are the snows of yester-year?

Where’s Heloise, the learned nun,

For whose sake Abeillard, I ween,

Lost manhood and put priesthood on?

(From Love he won such dule and teen!)

And where, I pray you, is the Queen

Who willed that Buridan should steer

Sewed in a sack’s mouth down the Seine?–

But where are the snows of yester-year?

White Queen Blanche, like a queen of lilies,

With a voice like any mermaiden–

Bertha Broadfoot, Beatrice, Alice,

And Ermengarde the lady of Maine–

And that good Joan whom Englishmen

At Rouen doomed and burned her there–

Mother of God, where are they then?–

But where are the snows of yester-year?

Nay, never ask this week, fair lord,

Where they are gone, nor yet this year,

Except with this for an overword–

But where are the snows of yester-year?

Life-In-Love

| Not in thy body is thy life at all But in this lady’s lips and hands and eyes; Through these she yields thee life that vivifies What else were sorrow’s servant and death’s thrall. Look on thyself without her, and recall The waste remembrance and forlorn surmise That liv’d but in a dead-drawn breath of sighs O’er vanish’d hours and hours eventual.Even so much life hath the poor tress of hair Which, stor’d apart, is all love hath to show For heart-beats and for fire-heats long ago; Even so much life endures unknown, even where, ‘Mid change the changeless night environeth, Lies all that golden hair undimm’d in death. |

Dante Gabriel Rossetti: Seven Poems

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: Rossetti, Dante Gabriel

Desiderius Erasmus

HET SPOOK OF DE DUIVELBANNING

deel I

THOMAS EN ANSELMUS

Hoe Erasmus reeds ver verheven stond boven de bijgeloovige begrippen van zijn tijd op ‘t gebied van spoken en duivelbanning, bewijst onderstaande samenspraak. Vinnig spot hij met de kunsten, zelfs door priesters en goed-geloovigen uitgehaald, en ‘t is niet te verwonderen dat zijn scherptreffende steken en prikken de geestelijkheid zijner dagen sterk tegen hem innamen. Vooral de lagere geestelijkheid was fel op hem gebeten en ‘t was slechts door hulp van vrienden onder de hoogere machthebbers in de kerk, zelfs te Rome, dat Erasmus de gevolgen van den door hem gewekten haat ontging.

Dat die haat diep geworteld zat, blijkt wel uit ‘t verhaal (waar of niet-waar) dat een zeker priester nimmer het portret van Erasmus, dat hij daartoe opzettelijk in zijn woning had opgehangen, voorbijging zonder er tegen te spuwen.

THOMAS: Wat blij nieuws is er dat je zoo vergenoegd bij je zelven lacht, alsof je een schat gevonden hadt?–ANSELMUS: Nu, zoo heel ver van de waarheid was je met je raden niet verwijderd.–THOMAS: Maar wil-je dan aan je vriend niet eens meedeelen wat dat voor goeds is?–ANSELMUS: ‘t Was al lang een hartewensch van me om iemand te hebben aan wiens boezem ik mijn vreugde kon uitstorten.–THOMAS: Welnu dan, deel mee.–ANSELMUS: ‘k Heb daareven een allerleukst verhaal gehoord waarvan je zoudt zweren dat ‘t een grappig verzinsel was, als niet plaats, personen en de heele zaak mij net zoo goed bekend waren als ik u ken.–THOMAS: Je maakt me brandend nieuwsgierig.–ANSELMUS: Je kent Polus, den schoonzoon van Faunus?–THOMAS: Heel goed.–ANSELMUS: Nu hij is ‘t die ‘t heele stukje heeft bedacht en heeft gespeeld.–THOMAS: Ik wil ‘t graag gelooven. Want hij kan zelfs zonder masker of vermomming elke rol spelen.–ANSELMUS: Zoo is het. Dan ken-je denk ik ook ‘t buitentje dat hij niet ver van Londen heeft?–THOMAS: Of ik! we hebben daar menigmaal een goed glaasje gedronken.–ANSELMUS: Dan kun-je je ook nog wel dien weg voorstellen aan beide kanten met boomen op gelijken afstand beplant?–THOMAS: Links van het huis een paar pijlschoten ver?–ANSELMUS: Juist. Aan den eenen kant van den weg is een drooge sloot, begroeid met kreupelhout en doornstruiken. Over een smal bruggetje kom-je van daar in ‘t open veld.–THOMAS: Ja, dat weet ik.–ANSELMUS: Al lang liep het gerucht en ‘t praatje onder de boeren van die plaats, dat bij dit bruggetje een spook werd opgemerkt, waarvan men zoo nu en dan de klagende jammerkreten kon vernemen. Men vermoedde dat ‘t de ziel van den een of ander was die door vreeslijke pijnigingen werd gekweld.–THOMAS: En van wien ging dat praatje uit?–ANSELMUS: Wel, van wien anders dan van Polus? Dat was het voorspel van zijn stuk.–THOMAS: Hoe kwam hij er zoo op om dat alles te verzinnen?–ANSELMUS: Weet ik? Of ‘t moet zijn omdat ‘t een eigenaardigheid van hem is. Hij houdt er van met de domheid van ‘t volk door zulke spelletjes den spot te drijven. Laat ik je eens vertellen wat van dien aard hij onlangs heeft uitgedacht. Gezamenlijk reden wij in nog al grooten getale te paard naar Richmond. Daar waren er onder, die je kloeke mannen zoudt kunnen noemen. Het was een prachtige, heldere hemel, door geen wolkje verduisterd.

Terwijl aller oogen naar den hemel gericht waren sloeg Polus over zijn voorhoofd en zijn borst een kruis en terwijl zich op zijn gezicht schrik afteekende, sprak hij half luid in zich zelf: “God Almachtig, wat zie ik daar?” En aan zijn gezellen die ‘t dichtst bij hem reden en hem vroegen wat hij zag, zei hij terwijl hij nog grooter kruisteekens maakte: “Moge de genadige God dit teeken afwenden.” Toen allen aandrongen om toch te weten te komen wat er was, zei hij met star op den hemel gevestigde blikken en terwijl hij met zijn vinger een plek aan den hemel wees: “Ziet ge daar dan niet dien ontzaglijken draak met vurige horens gewapend en met zijn staart in een kring gedraaid?” Toen allen zeiden dat ze niets zagen en hij zei dat ze dan toch hun oogen goed moesten inspannen en hij hun intusschen de plek bleef aanwijzen zei eindelijk een dat hij ‘t ook zag, om niet den schijn te hebben dat hij slechte oogen had. Een tweede volgde hem na en nog weer een. Want deze schaamde zich niet te zien wat voor anderen zoo duidelijk scheen te zijn. Om kort te gaan: binnen een drietal dagen was ‘t gerucht als een loopend vuurtje door geheel Engeland verspreid, dat zich zulk een verschijning had vertoond.

Verwonderlijk evenwel is het, hoeveel er in den mond van ‘t volk niet bijgekomen was. Ook waren er die in vollen ernst gingen uitleggen wat ‘t wonderteeken eigenlijk moest beduiden. Natuurlijk had hij die ‘t geheele stuk in elkaar gezet had ontzaglijk veel schik in de domheid der menschen.–THOMAS: O, ‘t is precies een bedenksel voor hem. Maar om tot je spook terug te keeren.–ANSELMUS: Intusschen komt juist bij Polus een zekere priester Faunus logeeren, een van die orde voor wie ‘t niet genoeg is dat ze met den latijnschen naam Regulieren worden genoemd, maar die er ook nog graag den griekschen naam kanunnik aan zien toegevoegd: kortom, een parochie-priester uit ‘t een of ander dorp in de buurt, een man die zich verbeeldde, vooral van zaken van den heiligen dienst nog al heel wat verstand te hebben.–THOMAS: Ik begrijp ‘t. Nu hebben we de acteurs in het stuk bij elkaar.–ANSELMUS: Aan den maaltijd werd gesproken over de praatjes aangaande het spook. Toen Polus bespeurde dat Faunus niet alleen ‘t gerucht vernomen had, maar ‘t ook geloofde, begon hij den man te bezweren dat hij, zoo’n geleerd en vroom man, de arme ziel, die zoo schriklijke plagen moest verduren, te hulp zou komen. “En,” zei hij, “als ge soms twijfelt, onderzoek dan de zaak, wandel tegen een uur of tien eens langs dat bruggetje en dan zul-je ‘t droevig gejammer hooren. Neem maar mee wien je wilt om je te vergezellen. Dan zul-je veiliger hooren en tevens zekerder.”–THOMAS: Nu, en verder?–ANSELMUS: Na ‘t eten gaat Polus, zooals gewoonlijk, weg om te jagen of op de vogelvangst. Terwijl Faunus oploopt naar ‘t bruggetje, toen ‘t al zoo donker was geworden dat men de omgeving niet duidelijk meer kon waarnemen, hoort hij eindelijk een klagend gezucht. Polus wist dat geluid allernatuurlijkst na te bootsen, terwijl hij verborgen zat in een boschje met een aarden kruik bij zich, waardoor zijn stem, die door de holte werd weerkaatst, nog ijslijker klonk.–THOMAS: Dit komediestuk overtreft nog ‘t spookstuk van den dichter Menander.[1]–ANSELMUS: Je zult dat nog met meer recht zeggen, wanneer je ‘t geheel hoort. Faunus keert naar huis terug, vol begeerte om te vertellen wat hij gehoord had. Polus was langs een korteren weg al eerder thuis gekomen. Daar vertelt Faunus aan Polus wat er gebeurd was en dikt het nog wat aan om ‘t nog verwonderlijker te maken.–THOMAS: Kon Polus intusschen zijn lach bedwingen?–ANSELMUS: Hij? Hij heeft zijn gelaatsspieren geheel in zijn macht. Men zou er op gezworen hebben dat ‘t een hoogst ernstige zaak gold. Eindelijk neemt Faunus, op sterk aandringen van Polus de taak van de duivelbanning op zich en brengt dien ganschen nacht in slapeloosheid door, terwijl hij overlegt hoe hij op veilige wijze de zaak zal aanpakken. Want hij was voor zijn eigen hachje leelijk bang. Eerst werden dus de meest uitwerkende uivelbanningsformulieren bijeengebracht, en hij voegde er nog eenige nieuwe bij, bijv. een: “bij de ingewanden der zalige Maagd Maria,” een ander: “bij het gebeente van de Heilige Werenfrieda.”

Vervolgens wordt er een plaats uitgezocht in ‘t open veld, dicht bij ‘t struikgewas waaruit de stem placht gehoord te worden: daaromheen was een tamelijk wijde cirkel getrokken, waarin verscheiden kruisteekens en andere figuren stonden. En dat alles geschiedde onder ‘t uitspreken van allerlei formulieren. Daarbij werd een groote bak geplaatst vol wijwater. Ook hing zich de duivelbanner een heilige stool om den hals, waarvan een perkament afhing dat ‘t begin bevatte van ‘t Evangelie naar Johannes. In een tasch droeg hij bij zich een wassenbeeldje, zulk een, als waarover de Paus jaarlijks zijn zegen uitspreekt en die men doorgaans “het Lam Gods” noemt. Met deze wapens beschermde men zich oudtijds tegen booze geesten, voordat de monnikspij van den Heiligen Franciscus van Assisi hun schrik had aangejaagd. Al deze voorzorgsmaatregelen waren genomen om te verhoeden dat de geest, als ‘t soms een booze was, op den duivelbanner een aanval zou doen. Maar hij durfde zich toch niet alleen toevertrouwen aan zijn cirkel. Men besloot er nog een tweeden priester bij te nemen. Nu werd Polus bang dat, als er een slimmerd bijgenomen werd, ‘t geheim van zijn komedie zou worden verraden, en hij gaf hem tot helper een pastoor uit de buurt, aan wien hij de geheele toedracht verhaald had. Dat toch eischte de geheele opzet van ‘t stuk en ‘t was iemand die van zoo’n stukje in ‘t geheel geen afkeer had. Toen op den volgenden dag alles behoorlijk gereed gemaakt was, stapt tegen tien uur Faunus met den pastoor zijn gewijden kring binnen. Polus, die vooruitgegaan was, heft uit het boschje zijn geweeklaag aan en Faunus begon nu ‘t banningswerk. Onderwijl sloop Polus heimelijk naar een naastbijzijnde boerderij. Vandaar brengt hij een nieuwen persoon mee voor zijn komedie, want die kon alleen gespeeld worden met behulp van velen.–THOMAS: Wat doen ze?–ANSELMUS: Ze bestijgen zwarte paarden en dragen brandende lantaarns bij zich, maar zoo dat ze die verborgen houden onder hun mantels. Toen ze niet ver van den kring af waren, hielden ze dit licht voor zich uit om Faunus bang te maken en uit zijn cirkel te verdrijven.–THOMAS: Wat een moeite deed die Polus toch om den ander te foppen!–ANSELMUS: Ja, zoo is hij. Maar dat zaakje was bijkans leelijk voor hem uitgekomen.–THOMAS: Hoe dan?–ANSELMUS: Wel, ‘t scheelde weinig of de paarden, verschrikt door dat zoo plotseling vertoonde licht, waren neergestort met hun berijders en al.

Noot:

[1] Grieksche comediedichter wiens stuk: het Spook, door den latijnschen

blijspeldichter Plautus bewerkt is, onder den titel van: Aulularia, het

Spookhuis.

Uit: Erasmus van Rotterdam, Een Twaalftal Samenspraken

(wordt vervolgd)

kemp=mag poetry magazine

More in: Desiderius Erasmus, MONTAIGNE

Joep Eijkens Photos

Dood waar is uw prikkel – II

fleursdumal.nl magazine – magazine for art & literature

Joep Eijkens Photos: Dood waar is uw prikkel – II

© J. Eijkens

More in: Galerie des Morts, Joep Eijkens Photos

E d u a r d M ö r i k e

(1804-1875)

Das Verlassene Mägdlein

Früh, wann die Hähne krähn,

Eh’ die Sternlein verschwinden,

Muß ich am Herde stehn,

Muß Feuer zünden.

Schön ist der Flammen Schein,

Es springen die Funken;

Ich schaue so drein,

In Leid versunken.

Plötzlich da kommt es mir,

Treuloser Knabe,

Daß ich die Nacht von dir

Geträumet habe.

Träne auf Träne dann

Stürzet hernieder:

So kommt der Tag heran–

O ging’ er wieder!

Poem of the week – November 23, 2008

kemp=mag poetry magazine

More in: Archive M-N

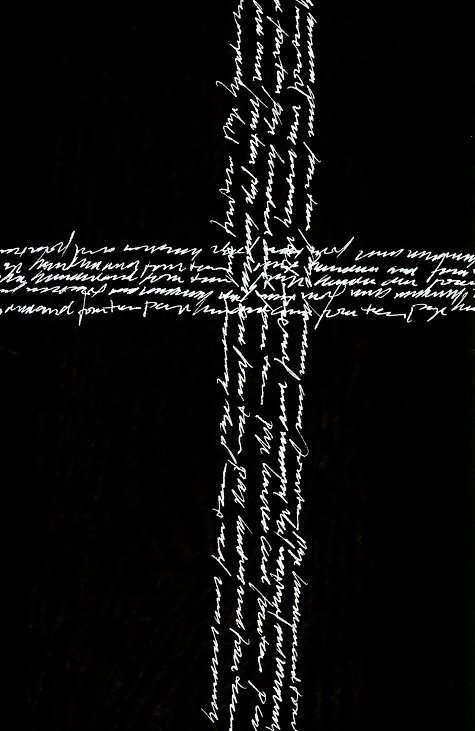

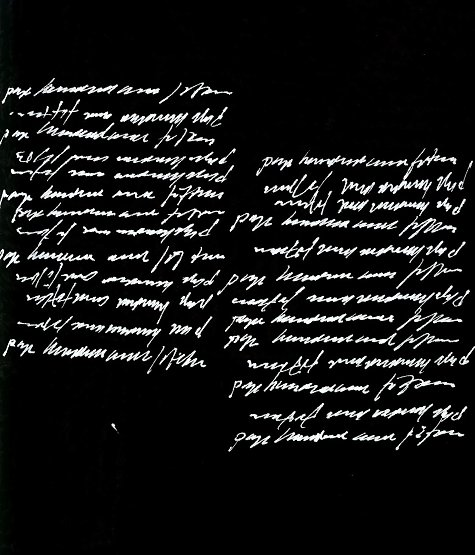

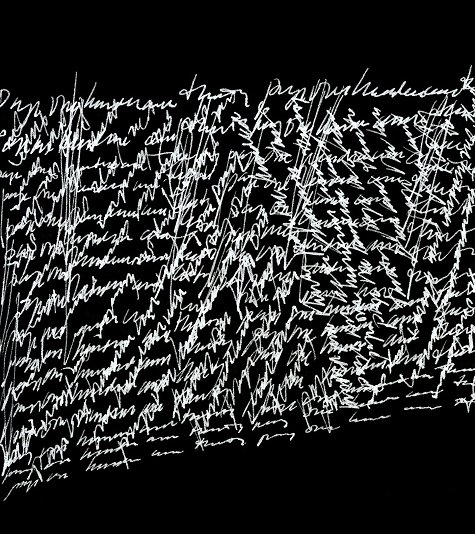

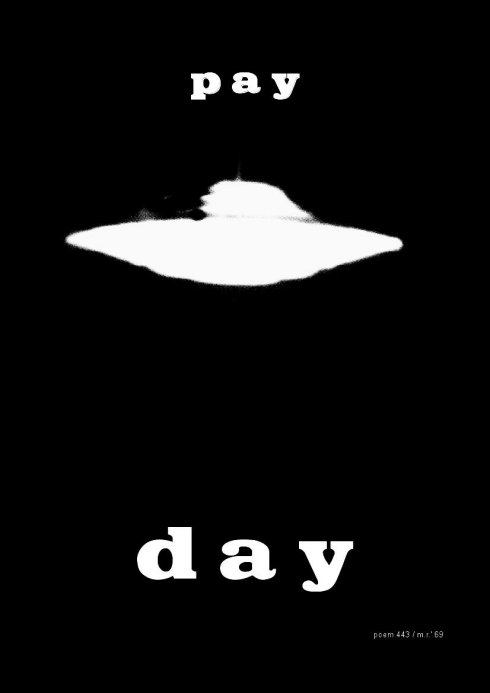

Monica Richter

Poem 443 / 1969

kemp=mag poetry magazine

More in: Monica Richter, Richter, Monica

.jpg)

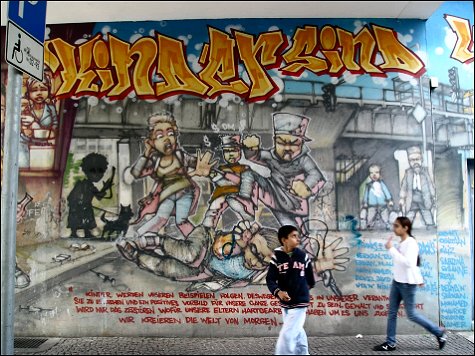

NACHRICHTEN AUS BERLIN

Unser Korrespondent Anton K. berichtet

Lesen in Berlin 5

fleursdumal.nl magazine

More in: FDM in Berlin, Graffity, Nachrichten aus Berlin

Thank you for reading Fleurs du Mal - magazine for art & literature